Abstract

Root colonization by endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica facilitating growth/development and stress tolerance has been demonstrated in various host plants. However, global metabolomic studies are rare. By using high-throughput gas-chromatography-based mass spectrometry, 549 metabolites of 1,126 total compounds observed were identified in colonized and uncolonized Chinese cabbage roots, and hyphae of P. indica. The analyses demonstrate that the host metabolomic compounds and metabolite pathways are globally reprogrammed after symbiosis with P. indica. Especially, γ-amino butyrate (GABA), oxylipin-family compounds, poly-saturated fatty acids, and auxin and its intermediates were highly induced and de novo synthesized in colonized roots. Conversely, nicotinic acid (niacin) and dimethylallylpyrophosphate were strongly decreased. In vivo assays with exogenously applied compounds confirmed that GABA primes plant immunity toward pathogen attack and enhances high salinity and temperature tolerance. Moreover, generation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species stimulated by nicotinic acid is repressed by P. indica, and causes the feasibility of symbiotic interaction. This global metabolomic analysis and the identification of symbiosis-specific metabolites may help to understand how P. indica confers benefits to the host plant.

Introduction

Piriformospora indica of the Sebacinales, Basidiomycota, can colonize a broad spectrum of plants1. The mutualistic symbiosis further promotes plant growth/biomass, and confer resistance/tolerance against biotic and abiotic stress2, 3. Due to its axenically cultivability, P. indica has been extensively used for studying the mechanisms and evolution of mutualistic symbiosis4. Finally, being able to promote growth significantly and deliver biotic/abiotic stress acclimation ability to its host, P. indica has great potential for biotechnological applications and future research for bio-agricultural engineering5.

The decoding of the fungal genome revealed that P. indica represents a missing link between a saprophytic fungus and an obligate biotrophic mutualist6. It holds genes for a biotrophic lifestyle, and lacks genes for nitrogen metabolism, but also matches characteristics of symbiotic fungi and obligate biotrophic pathogens6. The symbiotic interaction ultimately leads to growth promotion, increased biomass production, stimulation of the uptake of phosphate and other limiting ions, and enhanced tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses, as known from mycorrhizal fungi7, 8. Genetic and biochemical analyses revealed possible signal transduction processes induced by P. indica in the root cells of host plants9–11. Moreover, Stein et al.12 has shown that P. indica-induced resistance against powdery mildew in Arabidopsis host involves jasmonic acid (JA), but not salicylic acid (SA). Changes in plant abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellic acid (GA), JA, and SA levels affected root colonization in barley, and changes in the GA biosynthetic pathway suppressed P. indica-mediated defense responses13. Furthermore, sustained exposure to ABA enhances the colonization potential of P. indica on Arabidopsis roots14. Once inside the roots, the fungus benefits from the plant’s photoassimilates, which further promotes colonization and proliferation in particular environmental stress conditions15, 16. As in mycorrhiza, the fungus reprograms the plant transcriptome and proteome6, 15, 17. The P. indica-responsive genes provide a powerful toolbox to elucidate signaling and metabolic pathways involved in establishing the symbiosis and promoting plant performance.

In the past decade, we studied the beneficial interaction of P. indica with Chinese cabbage roots2, 7. Besides an overall stimulation of root and shoot growth by the endophyte, the substantial increment of lateral root development results in a bushy root phenotype. Such a strong stimulation of lateral root development has not yet been described for another plant species colonized by P. indica. This has prompted us to investigate the symbiotic interaction of P. indica with Chinese cabbage roots in more details, since the strong effect of the fungus on root growth and proliferation might be important for agricultural applications. We have demonstrated that the observed phenotype is associated with a strong, transient increase of the auxin level in the roots, which results in upregulation of Chinese cabbage genes correlated with growth- and auxin signaling-related functions, such as genes for P-type/V-type H+-ATPases and nutrient/ion transporters, root hair-forming phosphoinositide phosphatase 4 (RHD4), cell wall loosening/synthesizing proteins involved in cell wall growth, and auxin transportation/responses2. Some of the genes induced during the biotrophic phase of P. indica colonization harmonize the auxin level with the degree of root colonization. In-depth microscopic analyses of the root structure after successful symbiosis showed that the fungus stimulates primarily growth and development of the root maturation zone7.

While relatively much is known about the transcriptomic and proteomic changes in roots in response to colonization by beneficial fungi, systematic analyses of metabolomic profiles are still rare. Thus far, the induction of salicylic acid catabolites and jasmonate as well as glucosinate metabolism have been demonstrated correlating with the colonization of A. thaliana with P. indica 18, 19. Recently, Strehmel et al.20 investigated the metabolic response of A. thaliana to P. indica under hydroponic condition. Results showed that the profiles of primary and secondary metabolites were obviously changed in colonized roots, while far less significant change in leaves. The increased concentrations were found in organic acids, carbohydrate, ascorbate, glucosinates and hydroxycinnamic acids, and a decreased concentration found in nitrogen-rich amino acids. This important finding has contributed to validate the symbiotic mechanism between plant host and P. indica.

Following our previous study, in order to further understand the mechanisms of stress tolerance and growth promotion in Chinese cabbage caused by colonization of P. indica, we performed a comprehensive metabolomic analysis, in which the profiles of P. indica-colonized and uncolonized Chinese cabbage roots, and the profile of P. indica hyphae were comparatively surveyed. The data allow the identification of symbiosis-specific metabolites in P. indica-colonized Chinese cabbage roots, such as GABA and IAA derivatives. The results are helpful for validating the beneficial function triggered by P. indica-colonization. Most importantly, the mechanisms that growth promotion and abiotic/biotic stress tolerance are simultaneously enhanced by P. indica could be demonstrated based on the metabolomic data.

Results

Metabolome profiles of P. indica-colonized and uncolonized Chinese cabbage roots and P. indica hyphae

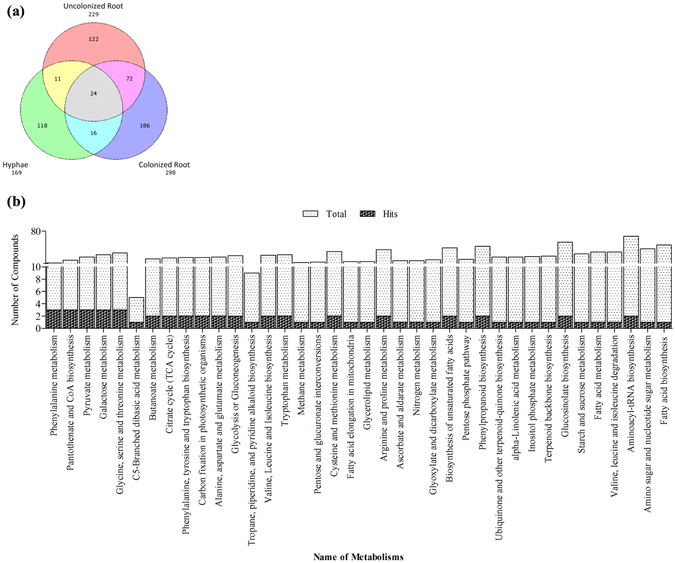

In order to identify metabolites induced or repressed in Chinese cabbage roots in response to P. indica colonization, three metabolomic libraries were generated: two from Chinese cabbage root extracts with and without P. indica inoculation, and one from a hyphal extract of P. indica. In all, 549 of a grand total 1,126 metabolites were identified from the GC-MS analysis. Of the 549 metabolites annotation uncovered, 298 compounds in preparations from P. indica-colonized roots, 229 compounds from uncolonized roots and 169 compounds from P. indica hyphae (Fig. 1a). The compounds identified in the preparation from the P. indica hyphae were subtracted from those identified in P. indica-colonized and uncolonized Chinese cabbage roots. The compounds which were identified in the P. indica-colonized, but not in uncolonized roots should be induced in the symbiotic interaction, and can be of plant or fungal origin. The compounds, which were present in uncolonized roots but not detectable in P. indica-colonized roots should be repressed by the fungus in the roots, and were of plant origin.

Figure 1.

Analysis of metabolomic data from B. campestris roots after P. indica colonization. (a) Venn Diagram showing the number of compounds in extracts from P. indica-colonized roots (Pi-Root), un-colonized roots (Root Only), and hyphae of the fungus (Pi Only). (b) Number of identified metabolites classified according to biological functions.

Metabolites from P. indica-colonized root extract were characterized and classified into global metabolic pathways by using MetPA software analysis. As shown in Fig. 1b, they generally belong to the carbohydrate and amino acid metabolisms and biosynthetic pathways for secondary metabolites. This suggested that root colonization of P. indica reprograms the global metabolism in cabbage.

P. indica induced metabolites associated with the host’s TCA cycle

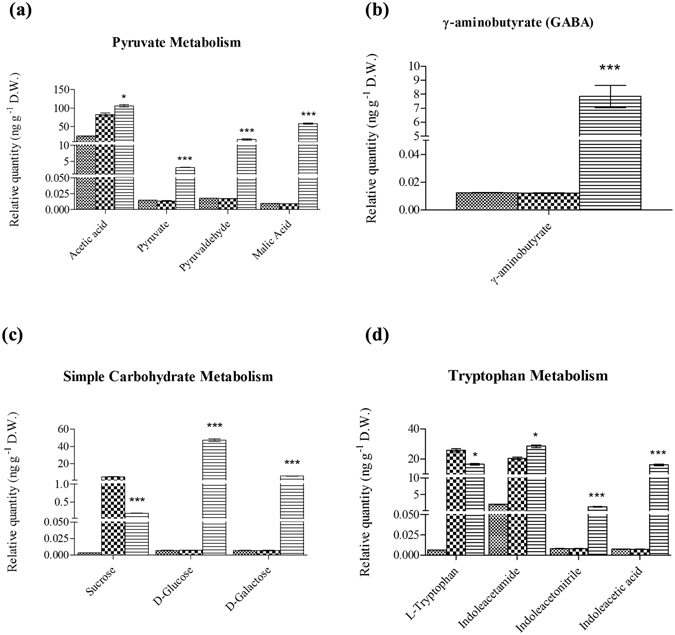

The levels of pyruvate, malic acid as well as pyruvaldehyde relative to the internal control (nonadecanoic acid-trimethylsilyl ester) were three to five times higher (mass per gram of dry weight) for P. indica-colonized Chinese cabbage roots compared to the uncolonized control (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2a). Notably, accumulation of pyruvaldehyde suggested that the side-products of the activated TCA cycle could not be removed fast enough in P. indica-colonized roots. Moreover, our previous transcriptome analyses identified mRNAs for enzymes participating in the pyruvate metabolism, which were induced by P. indica in Chinese cabbage roots7 (Table 1), such as hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase, malate synthase and malate dehydrogenase. Therefore, P. indica appears to stimulate the TCA cycle activity by accumulating metabolites involved in the pyruvate metabolism as well as by inducing genes required for the production of these metabolites. Equally important, mitochondria of plant host are likely the targets of P. indica in Chinese cabbage roots. Finally, the results also revealed that TCA cycle activity in the colonized roots might be stimulated to generate simple carbohydrates such as glucose and galactose (Fig. 2c) through the elevated pyruvate levels.

Figure 2.

Quantification of metabolites induced by P. indica in B. campestris roots. Relative quantification of (a) metabolites involved in TCA cycle; (b) γ-aminobutyrate; (c) metabolites involved in simple carbohydrate metabolisms; and (d) metabolites from auxin biosynthesis. Standard Error (SE) was calculated by three biological repeats taken by the average of each relative quantification from peak area acquired from GC-MS data analysis, p-value < 0.01 for significant among variables Hyphae, Uncolonized Root, Colonized Root for each compound. Legend:  Hyphae;

Hyphae;  Uncolonized Root and

Uncolonized Root and  Colonized Root.

Colonized Root.

Table 1.

List of genes identified by subtractive EST-analysis between: Hyphae, Colonized and Uncolonized roots.

| ORF name | Sequence length | SwissProt | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best hits and annotation | E-value | identity | Species | ||

| Fatty Acid Metabolism | |||||

| A181.seq | 1112 | gi|3334184|sp|Q39287.1|FAD6E_BRAJU Omega-6 fatty acid desaturase | 1.00E-68 | 94.26 | Brassica juncea |

| B93.seq | 1160 | gi|122223793|sp|Q0WRB0.1|FACR5_ARATH Fatty acyl-CoA reductase | 1.00E-145 | 85.71 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| C131.seq | 1146 | gi|114149941|sp|Q570B4.2|KCS10_ARATH 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase | 3.00E-55 | 97.3 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| D176.seq | 1092 | gi|75166464|sp|Q94KI8.1|TPC1_ARATH Two pore calcium channel protein 1 (TPC1) | 7.00E-70 | 94 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| H88.seq | 1174 | gi|3334184|sp|Q39287.1|FAD6E_BRAJU Omega-6 fatty acid desaturase | 5.00E-106 | 94.15 | Brassica juncea |

| I21.seq | 1291 | gi|134943|sp|P29108.1|STAD_BRANA Acyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] desaturase | 3.00E-111 | 99.52 | Brassica napus |

| Pheylalanine metabolism | |||||

| F92.seq | 1222 | gi|76803811|sp|P35510.3|PAL1_ARATH Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 1 | 1.00E-53 | 87.2 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| C177.seq | 1120 | gi|21542386|sp|P46645.2|AAT2_ARATH Aspartate aminotransferase | 6.00E-32 | 90.28 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| G71.seq | 1143 | gi|3915085|sp|P92994.1|TCMO_ARATH Trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase | 2.00E-78 | 98.18 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Pyruvate Metabolism | |||||

| F59.seq | 1102 | gi|11133446|sp|P57106.1|MDHC2_ARATH Malate dehydrogenase | 2.00E-22 | 72.53 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| I2.seq | 1252 | gi|11133398|sp|O82399.1|MDHG2_ARATH Probable malate dehydrogenase | 1.00E-158 | 93.14 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| D67.seq | 1192 | gi|3913733|sp|O24496.2|GLO2C_ARATH Hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase | 2.00E-67 | 92.13 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| C44.seq | 1097 | gi|75311439|sp|Q9LPR4.1|LEU11_ARATH 2-isopropylmalate synthase 1 | 3.00E-32 | 82.35 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Simple Carbohydrate Metabolism | |||||

| J36.seq | 1094 | gi|60389815|sp|Q9FXT4.1|AGAL_ORYSJ Alpha-galactosidase | 8.00E-36 | 58.02 | Oryza sativa Japonica |

| B146.seq | 1206 | gi|122215404|sp|Q3ECS3.1|BGL35_ARATH Myrosinase 5 | 3.00E-05 | 33.66 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| F7.seq | 1227 | gi|75171106|sp|Q9FJU9.1|E1313_ARATH Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase 13 | 3.00E-40 | 38.1 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

List of genes identified by subtractive EST-analysis7 that were matched with the metabolome analysis of 7 days P. inidica colonized Chinese cabbage root.

P. indica stimulated the synthesis of γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) and metabolites involved in the tryptophan and phenylalanine metabolism

GABA is a non-proteinous amino acid compound and accumulates rapidly in response to biotic and abiotic stress in plants21. It has been proposed to function as an osmo- and redox regulator and a plant-signaling molecule21–23. From the quantitative analysis, the GABA level was much higher in P. indica-colonized roots compared to the uncolonized controls, suggesting an important role in symbiosis (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2b).

From our previous reports, auxin level was evidently elevated in cabbage root tissues after colonization by P. indica. The higher the auxin level synthesized de novo in P. indica-colonized root tissues, the more it promotes growth and in particular the development of the bushy root architecture2, 7. The metabolic profile showed that three intermediates of the tryptophan metabolism are prominently induced in P. indica-colonized roots (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 2d). IAM (indoleacetamide), which is already present in P. indica hyphae and uncolonized roots, was strongly elevated during root colonization (Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 2d). In addition, indoleacetonitrile (IAN) and indoleacetic acid (IAA) could only be detected after root colonization (Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 2d). In contrast, tryptophan was less abundant in the colonized roots, possibly due to the intensive biosynthetic efflux into the auxin biosynthesis pathway. Overall, the current metabolite levels corresponded to the gene expression patterns from the subtractive EST library of P. indica-colonized and uncolonized roots2, 7. The present data further supported the important role of the tryptophan and indole metabolism for de novo biosynthesis of auxin in P. indica-colonized roots, which facilitates growth promotion in Chinese cabbage2, 7.

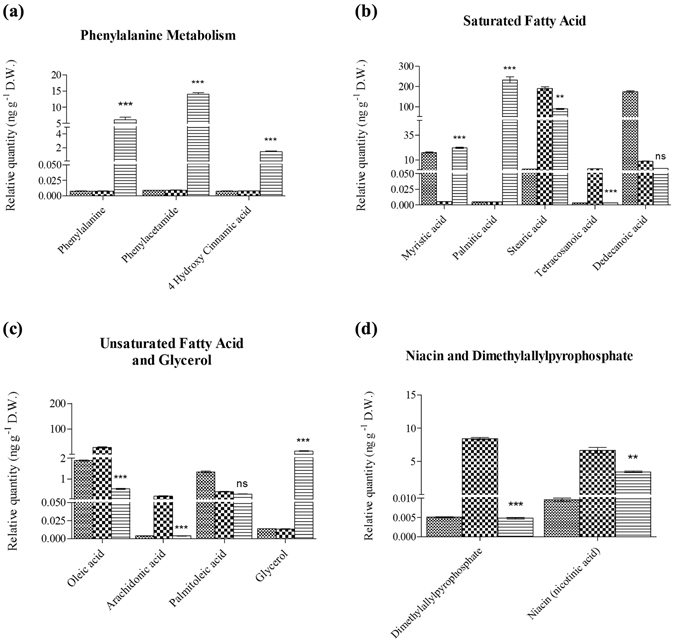

The tryptophan level was reduced in colonized roots, as compared to that in uncolonized roots, while auxin-biosynthetic intermediates were increased (Fig. 2d). This suggested that high amounts of tryptophan were utilized for the biosynthesis of intermediates of downstream steps in the related biosynthetic pathways. On the other hand, the compounds of the phenylalanine metabolism, such as phenylalanine, phenylacetamide and 4-hydroxy cinnamic acid were enhanced in P. indica-colonized roots (Fig. 3a). Coincidently, more ESTs for phenylammonia-lyase were present in the EST library of P. indica-colonized roots compared to a library from the uncolonized control2, 7 (and also in Supplementary Fig. S1). This suggested that many secondary metabolites involved in defense function were increased by P. indica-colonization.

Figure 3.

Quantification of metabolites that were reduced and altered by P. indica after colonization with B. campestris root. Relative quantification of (a) metabolites involved in phenylalanine metabolism; (b) saturated fatty acids; (c) unsaturated fatty acids and glycerol; and (d) nicotinic acid and dimethylalyl-diphosphate. Standard Error (SE) was calculated by three biological repeats taken by the average of each relative quantification from peak area acquired from GC-MS data analysis, p-value < 0.01 for significant among variables Hyphae, Uncolonized Root, Colonized Root for each compound. Legend:  Hyphae;

Hyphae;  Uncolonized Root and

Uncolonized Root and  Colonized Root.

Colonized Root.

P. indica altered fatty acid composition and saturation in Chinese cabbage

We also observed an increase in the saturated fatty acid levels, such as myristic and palmitic acid in colonized roots (Fig. 3b). Their amounts (ng per gram dry weight) were ten times higher in colonized roots compared to uncolonized roots (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids such as arachidonic acid, monounsaturated fatty acids and oleic acid decreased (Fig. 3c). Also, the glycerol level was higher (Fig. 3c) suggesting a stimulatory effect of P. indica on the anabolism of fatty acid biosynthesis. The increase in saturated and the decrease of unsaturated fatty acids24, suggested that P. indica primes Chinese cabbage roots to adapt to upcoming stress situations.

It has been well known that plants produce various types of oxygenated fatty acids, termed “oxylipins”, in responses to microbial infection or biotic/abiotic stresses. Usually, α-linolenic acid and arachidonic acid (C18:2 and C18:3) were the major precursors oxidized to 2-hydroperoxy by lipoxygenase25, 26. Jasmonic acid (JA) was present in P. indica-colonized roots, but below detectability in uncolonized roots and P. indica hyphae (Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, only low levels of the oxylipin precursors arachidonic acid (Fig. 3c) and linolenic acid (Supplementary Table 2, marked by*) were found in colonized roots relative to the uncolonized control. This demonstrated that the oxylipin production in the host was stimulated by P. indica, and that the endophyte was capable to induce oxygenated fatty acids (oxylipins) to promote stress tolerance.

Niacin and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAP) were repressed by P. indica in Chinese cabbage roots

P. indica reduced the niacin level in Chinese cabbage roots to half the amount of uncolonized roots (Fig. 3d). Niacin and other vitamin B complexes has been known to elevate plant innate immunity against fungal attack27. Thus, reducing the niacin level might reduce innate immunity and promote P. indica colonization. Likewise, dimethylallylpyrophosphate, an intermediate of the zeatin and ubiquinone biosynthesis, was reduced by P. indica (Fig. 3d). Zeatin was required for the synthesis of the terpenoid backbone, e.g. for cytokinins and sterols. Consequently, the levels of stigmast-5-en-3-ol and squalene seemed reduced after P. indica colonization (Supplementary Fig. S2b). This resulted in lower cytokinin levels, and an increase in the auxin to cytokinin ratio favorable for promoting root development.

Exogenous application of the GABA homolog, BABA, and niacin on Chinese improved abiotic and biotic stress adaptation

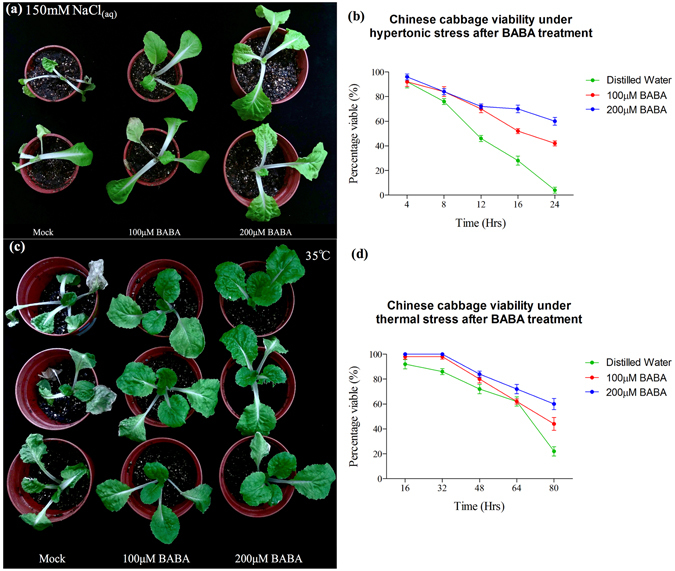

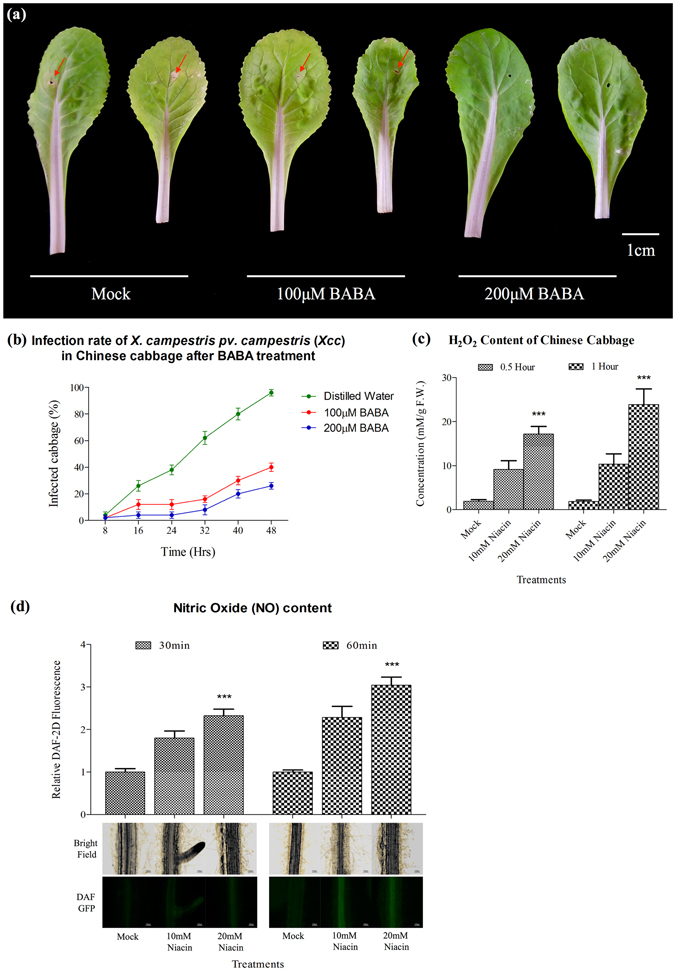

GC-MS analysis revealed an increase in GABA and a decreased in niacin contents during P. indica colonization (Figs 2b; 3d). To investigate a potential role of these two metabolites in the symbiotic interaction, exogenous application of GABA and niacin to Chinese cabbage was performed. As previously reported, BABA (β-aminobutyrate) functions similarly as GABA. It plays a priming compound to strengthen stress adaptation28, 29. Thus, we used BABA, instead of GABA, to apply exogenously on cabbage plants in this study. Twenty-four hours after spraying of a BABA solution (5 ml of a 100 μM or 200 μM solution) to the leaves, the seedlings displayed more tolerance to 150 mM NaCl and 72 h after spraying, their performance under high temperature stress (35 °C) was clearly better compared to the water-treated controls (Fig. 4a–d). Finally, if BABA-sprayed seedlings were inoculated with Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (Xcc), the black rot disease that affects Brassicacae worldwide, they performed better than the control seedlings (Fig. 5a,b).

Figure 4.

Exogenous application of β-aminobutyrate unto Chinese cabbage showed growth effect, salt and heat tolerance. (a) and (b) 21 DAG Chinese cabbage was shown to have more 24-hours hypertonic tolerance (150 mM NaCl) after exogenously treated with 100 μM and 200 μM BABA as compared to those treated with mock (distilled water). (c) and (d) 21 DAG Chinese cabbage was shown to have a higher thermal-stress tolerance (72 hours of 35 °C incubation) after exogenously treated with 100 μM and 200 μM BABA as compared to those treated with mock (distilled water). Quantifications of viable Chinese cabbage (c) and (d) were recorded from biological replicates of 10 Chinese cabbage and plotted against time (hours) with normal standard error.

Figure 5.

Exogenous application of β-aminobutyrate and niacin unto Chinese cabbage showed pathogenic tolerance and ROS/RNS generation. (a) and (b) 21 DAG Chinese cabbage were shown to have a higher immunity against Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (Xcc) (108 c.f.u.) after treated with 100 μM and 200 μM BABA as compared to those treated with mock (distilled water). Red arrow denotes the necrosis symptom. (c) Chinese cabbages were shown to have higher ROS level in the form of H2O2 after half-hour and an hour exogenous treatment of both 10 mM and 20 mM niacin (d) Confocal-microscopic analysis showed Chinese cabbage treated exogenously with 10 mM and 20 mM niacin as compared to those treated with mock (distilled water) have a higher NO content in the root for both half-hour and an hour treatment. Quantifications of viable Chinese cabbage (d) were recorded from biological replicates of 10 Chinese cabbage and plotted against time (hours) with normal standard error. NO and H2O2 levels were measured from biological replicates of 6 Chinese cabbage and statistical analysis were performed with standard ANOVA comparing the marked column to mock treatment, where ns = non-significant; *p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.001.

Furthermore, treatment with niacin (10 mM or 20 mM) on Chinese cabbage seedlings for 0.5 or 1 hour caused higher H2O2 and NO production (Fig. 5c,d). These results are consistent with the idea that P. indica represses niacin and thus less H2O2 and NO production to allow more efficient root colonisation.

Discussion

In this paper, we identified plant host metabolites, which are stimulated or repressed by P. indica to optimize root colonization and plant performance. As shown in Fig. 6, the pathways targeted by P. indica belong to the primary and secondary metabolisms, defense compounds, and signaling compounds. Their regulation by P. indica is consistent with the beneficial effect of the fungus on the performance of Chinese cabbage. In a previous study with root tissue of A. thaliana, Strehmel et al.20 demonstrated that nearly all metabolite levels increased upon co-cultivation in root extracts, except those in leaves. These included carbohydrates, organic acids, amino acids, glucosinolates, oligolignols, and flavonoids. Our current findings with Chinese cabbage resemble those from A. thaliana. Generally, the primary metabolism is activated, and the levels of metabolites in primary metabolism are increased. This indicates that P. indica can perform largely similar symbiotic function with Chinese cabbage and A. thaliana. Although some cases of different level, such as for pyruvate and niacin, were observed in Chinese cabbage when compared to A. thaliana. This might be caused by species-specific differences, but also by the fact that the response of Chinese cabbage to P. indica colonization seems to be stronger than the responses described for A. thaliana. Overall, the metabolomic profiles demonstrate that P. indica stimulates the energy status of the roots, trigger the accumulation of metabolites, which promote growth, and they are consistent with developmental processes and phenotypic changes.

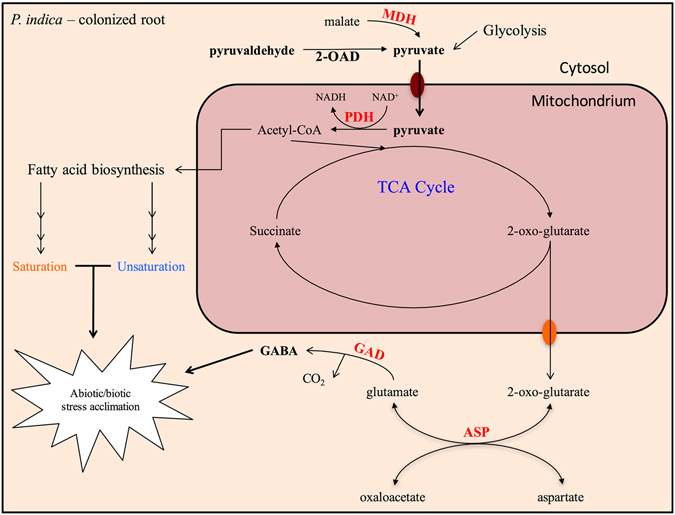

Figure 6.

Proposed diagram showing the changes in metabolic pathways along with metabolites and genes induced by P. indica after colonization. Metabolites involved in the pyruvate metabolism are altered after 7 days of P. indica colonization in Chinese cabbage root. Elevation of metabolites involved in pyruvate metabolism consequently trigger (1) fatty acid biosynthesis and (2) TCA cycle, which produces 2-oxo-glutarate and elevates GABA. P. indica-induced GABA promotes abiotic stress acclimation and impedes growth of plants; whereas, L-glutamine or glutamate that could be produced via P. indica-induced pyruvate and –activated TCA cycle negates such effect as proposed49. List of genes induced by P. indica (marked in red) from previous EST-library7 ASP: aspartate aminotransferase. GAD: glutamate decarboxylase. MDH: malate dehydrogenase. 2-OAD: 2-oxaloacetic dehydrogenase. PDH: pyruvate dehydrogenase.

We have demonstrated an elevation of metabolites involved in the pyruvate metabolism and detected higher levels of pyruvate, pyruvaldehyde and malate of the TCA cycle in colonized roots (Figs 2a and 6). Since pyruvate is located at the junction of assimilatory and dissimilatory reactions30, the higher the pyruvic and malic acid levels it could likely activate the host’s TCA cycle for energy generation required for root growth and consumption by the fungus. Furthermore, the fungus could provide additional pyruvate and malic acid to the roots via lactic and acetic acids, which accumulate during previously described fungal-growth in the maturation zone7. Pyruvaldehyde, which accumulates in P. indica-colonized roots, is a cytotoxic side-product of glycolysis and is synthesized from the pyruvate metabolism. It is detoxified to S-lactoylglutathione by lactoylglutathione lyase, which is induced for oxidative stress tolerance in plants31, 32. Moreover, lactoylglutathione lyase is identified in our previous EST library to be induced by P. indica after colonization of Chinese cabbage roots. Therefore, P. indica may stimulate the accumulation of these metabolites in this symbiosis to support the enormous growth requirement and stress adaptation.

Exogenous application of indoleacetamide (IAM) has led to the biosynthesis of auxin and the activation of auxin-responsive genes in Oryza sativa, Sorghum bicolor, Medicago truncatula, and Populus trichocarpa 33. The P. indica - derived IAM (Fig. 2d) that we observed is likely to stimulate auxin biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage roots. In the previous study, we reported that auxin and mRNA levels for auxin-signaling related genes were transiently increased during the early colonization period of Chinese cabbage roots2, 7. The increased level of auxin correlates with growth promotion and biomass production. Additionally, Hilbert et al.34 proposed that the IAM derived from P. indica plays an important role in the establishment of a mutual symbiosis with Arabidopsis, which may also be true for the interaction of P. indica with B. campestris roots. Also, Schafer et al.13 demonstrated a local accumulation of both plant and fungal IAA during the initial phase of the P. indica/barley interaction. These observations support our data that fungus-derived IAM stimulates IAA production and participates in promoting root growth. On the contrary, there were not any cytokinin and GA derivatives found in this study. These are in consistent with our previous studies in the subtractive EST library2, 7.

Aromatic amino acids, such as tryptophan, phenylalanine and tyrosine contribute to the high fluxes of fixed carbon through the shikimate pathway, and this can vary between 20 to 50%35, 36. We observed different regulation of aromatic acids and defense-related precursors: while some of them are up-regulated (e.g. phenylalanine, and 4-hydoxy cinnamic acid), others are down-regulated (in particular tryptophan). Within the plant kingdom, the phenylalanine metabolism along amino acid metabolisms are important for the synthesis of phenol derivatives such as coumarin, monolignal, lignin, spermidin, flavonoid and tannin. Genes involved in plant phenolic secondary metabolism such as phenylammonia-lyase37, which is frequently used as case studies of plant defense evolution38, has been identified in our EST library2, 7 (also in Supplementary Fig. S1). Similarly, important for a more efficient host-colonization, tryptophan, the precursor of many defense compounds or compounds with antimicrobial activities is decreased in P. indica-colonized cabbage roots (Fig. 2d). This suggests that tryptophan is intensively utilized to synthesize IAA, defense compounds, such as alkaloids, flavonoids, lignins and aromatic antibiotics36, which also lead to enhanced antimicrobial tolerance. To our knowledge, such regulation has not yet been reported in previous studies. Both metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses suggest that P. indica induces compounds from the phenylalanine metabolism for adaptation to prevail environmental conditions; while tryptophan is required for root defense and IAA-mediated root growth. This is consistent with the idea that the strongly growing roots in the symbiosis must be prepared for stress situations, e.g. by priming early stress responses through the mild induction of stress-related processes. On the other hand, the fungus must ensure that its nutritional state is balanced which is achieved by the sufficient amino acid supply from the host39.

GABA has been reported as a non-proteinous amino acid functioning as an important neurotransmitter in animal systems21. It has been found intra- as well as extracellularly, and proposed to be involved in the interaction of plants with a wide range of other organisms including pathogenic fungi, but also participates in developmental processes22, 40, 41. GABA is synthesized from glutamate by the root-specific glutamate decarboxylase40 (Fig. 6). The process is essential for sustaining ROS levels in plants42. Additionally, it has been shown that GABA production was prominent in the mitochondria in the presence of ROS to be metabolized along with pyruvate by GABA transaminase (GABA-T) to alanine and succinic semialdehyde (SSA)43. SSA is toxic for plants and there are two known pathways for SSA metabolisms: oxidization to succinate via SSA dehydrogenase (SSADH) or reduction to γ-hydroxybutyrate by glyoxylate reductase44. SSADH is located in mitochondria45, 46, and appears to be the main enzyme for SSA removal since mutants for this enzyme suggest its significant role in heat stress adaptation and development22.

BABA (β-aminobutyrate), a GABA homolog, was shown to induce resistance against root- and soil-borne pathogens in tomato and cotton, as GAGA47, 48. The perception mechanism of BABA has been identified in Arabidopsis. Recently, BABA was detected in Arabidopsis and several plants including B. rapa, Z. mays, etc.,. It is very clear that BABA was naturally present in planta, and having identical function with its isomers: AABA (α-aminobutyrate) and GABA (γ-aminobutyrate)28, 29, 49. In agreement with previous studies, our treatment of BABA confirmed that the homologous priming component, GABA induced by P. indica, could activate a PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) response against pathogen infections (Fig. 5a,b).

Niacin or nicotinic acid is involved in the ROS burst in response to fungal infection. A. thaliana mutants fin4-1 and fin4-3 which lack de novo niacin biosynthesis, has lower ROS levels after fungal infection and does not triggered PTI or other immune responses50. Our results show that niacin-treated Chinese cabbage produces higher levels of nitric oxide and H2O2 (Fig. 5c,d). The lowered level of niacin occurring during symbiotic interaction implicates that it is downregulated to reduce plant immunity to facilitate the successful colonization of P. indica (Fig. 3d). Moreover, our analyses also show that the level of dimethylallylpyrophosphate (dimethylallyl-PP) is decreased (Fig. 3d). This metabolite is an intermediate for zeatin production and required for the mevalonate pathway to synthesize terpenoids, cytokinins and sterols51, 52. Even though terpenoids and cytokinins were not identified in the GC-MS analysis, the fungus is highly specific in regulating defense compounds in the host roots by lowering cholesterol derivatives which again may favor root colonization (Supplementary Fig. S2b). Despite lower ROS/RNS and sterol levels in colonized roots, the plants were not prone to pathogen (Xcc) attack (Fig. 5a,b). Previous findings showed that P. indica stimulated JAs and SA in A. thaliana for biotic stress adaptation53. Thus, it is conceivable that ROS production is only one defense compound among others and the sum of their regulation allows the fungus to balance defense and growth responses of the host. Moreover, earlier findings in A. thaliana showed that the amount of several cytokinins (isopentenyladenosine, cis-zeatin riboside and trans-zeatin riboside) were induced while others were not affected or decreased54. The reduced dimethylallyl-PP level detected in Chinese cabbage could also lead to lower cytokinin levels which ultimately establish a cytokinin-to-auxin ratio favorable for root growth.

Plants change their fatty acid composition to acclimate to higher temperatures: polyunsaturated fatty acids decrease and saturated fatty acids increase upon increasing temperature55–57. Consequently, mutants deficient in lipid unsaturation show enhanced thermal tolerance24, 58, 59. Oleic acid and arachidonic acid were shown to act as signaling molecules that modulate plant stress responses60, 61. We have observed that P. indica colonization increase the production of saturated fatty acids and decrease the production of unsaturated fatty acids in B. campestris. In our study, the increased level of polysaturated fatty acids and the decreased polyunsaturated fatty acids observed in P. indica-colonized roots suggested that the cell membrane fluidity is higher and innate immunity is lower. When plants are challenged by pathogens, lipase are activated to release unsaturated fatty acids which are subsequently transformed to oxylipins with diverse functions against microbial and insect attacks25. JA and its precursors, oxo-phytodienoic acids are regulating defense mechanism and balance growth and defense responses26. Although the oxylipin levels were not separately analysed in our work, the JA level is higher in P. indica-colonized roots (Supplementary Table 1), and the linolenic and arachidonic acid levels are reduced (Supplementary Table 2). These results demonstrate that P. indica colonization of Chinese cabbage roots may stimulate oxylipin biosynthesis via the degradation of unsaturated fatty acids.

Plants perform a tradeoff to optimize growth and acclimation to biotic and abiotic stress62, 63. P. indica promotes growth under drought stress in Chinese cabbage suggesting that the fungus shifts the balance towards growth2, 7, 64. Regulation of the levels of pyruvate, GABA, niacin and fatty acids by P. indica might be important to shift the balance towards growth promotion, in parallel enhancing the ability to respond to biotic and abiotic stress. Furthermore, pyruvate and L-glutamate as the intermediates of GABA biosynthesis are likely targets of the fungus to allow better plant performance under stress (Fig. 6). In conclusion, the identified metabolite changes induced by P. indica influence the biochemistry of the roots and might participate in the genetic reprogramming of root development, the symbiotic interaction, stress adaptations, and pathogen defenses. Finally, the interplay of auxin with other metabolic pathways need to be investigated in more details and at the cellular level, in particular since growth processes are controlled by local phytohormone maxima which are likely altered by P. indica in colonized roots.

Materials and Methods

Growth conditions of Chinese cabbage seedlings and P. indica, and estimation of plant growth promotion

Seeds of Chinese cabbage (B. campestris subsp. chinensis) were donated by Ming-Hong Seed Company, Taichung City, Taiwan. Seeds were sterilized with 75% alcohol for 10 min, then placed on a petri dish containing ½ MS nutrient medium65. Plates were incubated at 22 °C under continuous illumination (100 μmol m−2 s−1) for seed germination.

Seven days after seed plating on ½ MS medium, the growing seedlings were transferred to fresh plates containing ½ MS medium. One to six seedlings were used per petri dish and one fungal plague or one agar plague without fungus of 5 mm in diameter per seedling was placed at a distance of 1 cm from the roots. The colonized seedlings along with uncolonized ones were incubated at 22 °C under continuous illumination (50–55 μmol m−2 s−1). P. indica was cultured as described previously66, 67 on Kaefer medium. Seedlings were removed from the plates 7 days after co-cultivation and the roots were used for the extraction of secondary metabolites and GC-MS analyses. The results are presented on the basis of root fresh weights. Alternatively, the seedlings were transferred to pots and grown in a walk-in growth chamber, as described previously11.

Secondary metabolite extraction and partitioning from plant and fungal material

All chemical reagents were of analytical grade. The silylation reagents were MTBSTFA [N-Methyl-N-(t-butyldimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide] and the extraction reagents were ethylacetate, acetone and distilled water.

Roots from seven-day-old Chinese cabbage (B. campestris subsp. chinensis) were harvested from 5 to 7 Petri dishes containing ½ MS nutrient medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962). The stems and leaves were disposed. Equal sample amounts of seedlings inoculated with P. indica or without P. indica were used for metabolite extraction. The three samples [roots with P. indica (colonized root), roots without P. indica (uncolonized root) and P. indica mycelium (hyphae)] were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen after removed from the whole plant. The frozen samples were then incubated overnight (16 h) in a Labconco FreeZone® Freeze Dry System which was pre-chilled with liquid nitrogen.

The samples were removed from the freeze dryer, weighted and kept in liquid nitrogen under low light conditions [<100 μmol m−2 s−1]68 to prevent degradation of light-sensitive secondary metabolites. The three samples were then ground under the same light conditions with mortar and pestle prior to incubation in 100% ethanol overnight in the dark. The ethanol was removed with a Hydrion Scientific® rotary evaporator in the dark and the remaining material was weighted.

Partitioning of the secondary metabolites from the three samples was performed with ethyl acetate (EA) and water. 500 ml EA and 50 ml of milli-Q water were added to each sample in the dark. The suspensions were sonicated for 5 minutes before churning in order to dissolve the secondary metabolites in the heterogeneous mixture of EA and water. The two-phase suspensions of the three preparations were incubated overnight in the dark phases to obtain optimal phase separation, and the phases were then separated with separation funnels in the dark. The EA phases were used for further analyses and the solvent was removed in the dark with a rotary evaporator. The partitioning was carried out three times and the water fractions (containing mainly polysaccharides, proteins and unstable compounds) were discarded. Finally, the weights of the dried EA extracts were determined.

GC-MS data analysis

The analysis was performed as described by Gobel and Feussner69. Dry materials of the three samples Hyphae, Uncolonized root, and Colonized root were re-suspended in GC-MS grade methanol (200 ng/μl). Silylation was performed using MTBSTFA under 80 °C for 2 h. The separation conditions on an Rtx-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) for GC-MS analysis was set as follows: column flow, 1 ml/min helium; injector temperature, 250 °C; GC temperature program: 40 °C for 1 min, increase to 300 °C in 10 °C/min changes, 300 °C for 8 min; solvent delay, 470 sec; transfer line temperature, 280 °C; pegasus acquisition rate, 10 spectra/sec; mass range saved: m/z 50–600; ion source temperature: 200 °C. GC-MS was performed using the Pegasus® 4D GCxGC-TOFMS from Leco.

Three sets of data were collected from three independent biological repetitions; and analyzed using the program ChromaTOF® Software from Leco, by setting the threshold for up to 650 hits on m/z similarity and compared with the metabolites present in libraries of the software. Compounds with peak-areas below 700 were undetectable and compounds with less than 650 hits for m/z identification were removed. The identified compounds without silylation were individually analyzed; annotated and synthetic compounds were removed. Their abundance was calculated and quantified relatively to the internal control nonadecanoic acid-trimethylsilyl ester, which was added before the extraction and partitioning procedures and GC-MS analyses. Undetected peaks of any given compound from any given sample preparations: Hyphae, Uncolonized Root, or Colonized Root were calculated using threshold value of 700 for peak area. Moreover, the identified compounds were mapped to metabolomic pathways using the KEGG online software.

Bioinformatics

The metabolites identified from the GC-MS were analyzed with the MetPA online software to position them into global metabolic pathways. The analytical settings for MetPA were used for Fisher’s Exact test. The MetPA software annotated compounds of P. indica-colonized and uncolonized roots, as well as those of P. indica hyphae were matched to A. thaliana and yeast databanks. Additionally, MetPA software contains a series of programs with matches for the metabolic pathways found in their databases, and assigns the compounds to these pathways with their p-values. Figures and tables were generated from the MetPA analysis.

Exogenous application of β-aminobutyrate and niacin on Chinese cabbage for phenotypic and reactive oxygen species (ROS) analysis

One set of Chinese cabbage seeds were sterilized as previously mentioned above, each set containing eighteen, and then were sown unto petri dish containing 1/2 MS nutrient medium65. Five days after germination, they were transferred to ½ MS as well as ½ MS containing 100 μM and 200 μM filter-sterilized (45 μM filter) BABA. All six seedlings from one set and each treatment were recorded for stem and root length in centimeters, while two seedlings from each set of treatments were taken for phenotypic analysis by taking photograph of them aligned with each other.

Two more sets of Chinese cabbage seeds were sterilized, each set containing six, and then were sown unto petri dish containing ½ MS nutrient medium65. Five days after germination, they were transferred unto ½ MS as well as ½ MS containing 10 mM and 20 mM filter-sterilized (45 μM filter) niacin (Sigma-Aldrich, CAS 59–67–6, synonym to nicotinic acid); one set for 30 minutes and the other set for 1 hour respectively. Each set was used for NO quantification by following protocols using diaminofluorescein (DAF-2DA)70 staining and H2O2 by following procedures using titanium oxalate.

Twenty-seven Chinese cabbage seeds were sterilized as mentioned above and sown into twenty-seven 6-inch pots containing autoclaved soil/vermiculite mixture. After fourteen days, they were grown into Chinese cabbage plantlets and were used to perform thermal, high-salinity and biotic stress tolerance experiments, as described below in the following procedure.

Exogenous application of β-aminobutyrate on Chinese cabbage for phenotypic analysis after thermal-stress and biotic-stress treatment

Two sets of Chinese cabbages, each set containing nine 21- DAG plants, were used for the thermal and biotic stress analysis. One set was subjected under a 72 hours thermal stress (35 °C) with three plants treated with 100 μM BABA and another three with 200 μM BABA by spraying each plant with 10 mL of respective concentration unto their leaves. The last three plants were sprayed with 10mL-distilled water, since the solvent vehicle for BABA was distilled water. After 24, 48, and 72 hours, nine of the plants were taken for phenotypic changes observation and a photograph was taken.

The second set of Chinese cabbages were used for a 24 hours high-salinity stress analysis. Exogenous application of BABA was identical to what was mentioned above. However, 150 mM of dissolved NaCl was used for the high salinity treatment for all nine plants. After 24 hours, phenotypic changes were recorded by taking photographs of the plants.

The final set of Chinese cabbages was used for a 72 hours biotic stress analysis. Exogenous application of BABA was identical to what was mentioned above. Here, Xanthomonas campestris pv campestris (Xcc) was used as the pathogen to induce infection in Chinese cabbage. The third leaf of the whole plant from each set was firstly pierced with a hypodermic needle. Next, they were infiltrated with O.D. 0.2 or 108 c.f.u. amount of Xcc through the piercings. After 72 hours (which is the tested time for 0.2 O.D. amount of Xcc to infect Chinese cabbage with symptoms of rotting on leaf), the leaves from each treatment: water, 100 μM and 200 μM BABA were cut and photographed.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, under the project MOST-104-2311-B-002-008 to Dr. Kai-Wun Yeh. The work was also partially supported by the PPP project between Taiwan and Germany bilateral scientific agreement, NSC-102-1q11-T-002-510 to Dr. Kai-Wun Yeh, and to Dr. Ralf Oelmuller. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest exist.

Author Contributions

M.S.H. and Y.-B.C. conceived, implemented and performed the experiments. R.S.K. and L.-F.S. performed biostatistical analysis and assisted in the interpretation of all results. K.-W.Y. and R.O. coordinated and designed the overall experimental work. M.S.H. wrote manuscript. K.-W.Y. and R.O. critically revised the complete structure and organization of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08715-2

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ralf Oelmüller, Email: b7oera@uni-jena.de.

Kai-Wun Yeh, Email: ykwbppp@ntu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Franken P. The plant strengthening root endophyte Piriformospora indica: potential application and the biology behind. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2012;96:1455–1464. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4506-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee YC, et al. Growth Promotion of Chinese Cabbage and Arabidopsis by Piriformospora indica Is Not Stimulated by Mycelium-Synthesized Auxin. Mol Plant Microbe In. 2011;24:421–431. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-10-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unnikumar KR, Sree KS, Varma A. Piriformospora indica: a versatile root endophytic symbiont. Symbiosis. 2013;60:107–113. doi: 10.1007/s13199-013-0246-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varma A, et al. Piriformospora indica, a cultivable plant-growth-promoting root endophyte. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2741–2744. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2741-2744.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oelmuller R, Sherameti I, Tripathi S, Varma A. Piriformospora indica, a cultivable root endophyte with multiple biotechnological applications. Symbiosis. 2009;49:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s13199-009-0009-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuccaro A, et al. Endophytic life strategies decoded by genome and transcriptome analyses of the mutualistic root symbiont Piriformospora indica. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong SQ, et al. The maturation zone is an important target of Piriformospora indica in Chinese cabbage roots. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:4529–4540. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill, S. S. et al. Piriformospora indica: Potential and Significance in Plant Stress Tolerance. Front Microbiol7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Camehl I, et al. The OXI1 kinase pathway mediates Piriformospora indica-induced growth promotion in Arabidopsis. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahollari B, Vadassery J, Varma A, Oelmuller R. A leucine-rich repeat protein is required for growth promotion and enhanced seed production mediated by the endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2007;50:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vadassery J, Tripathi S, Prasad R, Varma A, Oelmuller R. Monodehydroascorbate reductase 2 and dehydroascorbate reductase 5 are crucial for a mutualistic interaction between Piriformospora indica and Arabidopsis. Journal of plant physiology. 2009;166:1263–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein E, Molitor A, Kogel KH, Waller F. Systemic resistance in Arabidopsis conferred by the mycorrhizal fungus Piriformospora indica requires jasmonic acid signaling and the cytoplasmic function of NPR1. Plant & cell physiology. 2008;49:1747–1751. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schafer P, et al. Manipulation of plant innate immunity and gibberellin as factor of compatibility in the mutualistic association of barley roots with Piriformospora indica. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2009;59:461–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peskan-Berghofer, T. et al. Sustained exposure to abscisic acid enhances the colonization potential of the mutualist fungus Piriformospora indica on Arabidopsis thaliana roots. The New phytologist (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Sherameti I, et al. The endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica stimulates the expression of nitrate reductase and the starch-degrading enzyme glucan-water dikinase in tobacco and Arabidopsis roots through a homeodomain transcription factor that binds to a conserved motif in their promoters. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:26241–26247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadav V, et al. A phosphate transporter from the root endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica plays a role in phosphate transport to the host plant. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:26532–26544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.111021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Deshmukh S, et al. The root endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica requires host cell death for proliferation during mutualistic symbiosis with barley. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:18450–18457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605697103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahrmann U, et al. Mutualistic root endophytism is not associated with the reduction of saprotrophic traits and requires a noncompromised plant innate immunity. The New phytologist. 2015;207:841–857. doi: 10.1111/nph.13411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vahabi K, Camehl I, Sherameti I, Oelmuller R. Growth of Arabidopsis seedlings on high fungal doses of Piriformospora indica has little effect on plant performance, stress, and defense gene expression in spite of elevated jasmonic acid and jasmonic acid-isoleucine levels in the roots. Plant Signal Behav. 2013;8 doi: 10.4161/psb.26301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strehmel, N. et al. Piriformospora indica Stimulates Root Metabolism of Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Roberts MR. Does GABA Act as a Signal in Plants?: Hints from Molecular Studies. Plant Signal Behav. 2007;2:408–409. doi: 10.4161/psb.2.5.4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouche N, Fait A, Bouchez D, Moller SG, Fromm H. Mitochondrial succinic-semialdehyde dehydrogenase of the gamma-aminobutyrate shunt is required to restrict levels of reactive oxygen intermediates in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:6843–6848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037532100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lancien M, Roberts MR. Regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana 14-3-3 gene expression by gamma-aminobutyric acid. Plant, cell & environment. 2006;29:1430–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alfonso M, et al. Unusual tolerance to high temperatures in a new herbicide-resistant D1 mutant from Glycine max (L.) Merr. cell cultures deficient in fatty acid desaturation. Planta. 2001;212:573–582. doi: 10.1007/s004250000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howe GA, Schilmiller AL. Oxylipin metabolism in response to stress. Current opinion in plant biology. 2002;5:230–236. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blee E. Impact of phyto-oxylipins in plant defense. Trends in plant science. 2002;7:315–322. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahn IP, Kim S, Lee YH. Vitamin B1 functions as an activator of plant disease resistance. Plant physiology. 2005;138:1505–1515. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.058693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thevenet D, et al. The priming molecule beta-aminobutyric acid is naturally present in plants and is induced by stress. The New phytologist. 2017;213:552–559. doi: 10.1111/nph.14298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luna E, et al. Plant perception of beta-aminobutyric acid is mediated by an aspartyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:450–456. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pronk JT, Yde Steensma H, Van Dijken JP. Pyruvate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1996;12:1607–1633. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199612)12:16<1607::AID-YEA70>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon K, et al. Novel glyoxalases from Arabidopsis thaliana. The FEBS journal. 2013;280:3328–3339. doi: 10.1111/febs.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Racker E. The Mechanism of Action of Glyoxalase. J Biol Chem. 1951;190:685–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sánchez-Parra B, et al. Characterization of Four Bifunctional Plant IAM/PAM-Amidohydrolases Capable of Contributing to Auxin Biosynthesis. Plants. 2014;3 doi: 10.3390/plants3030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilbert M, et al. Indole derivative production by the root endophyte Piriformospora indica is not required for growth promotion but for biotrophic colonization of barley roots. The New phytologist. 2012;196:520–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corea OR, et al. Arogenate dehydratase isoenzymes profoundly and differentially modulate carbon flux into lignins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:11446–11459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maeda H, Dudareva N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino Acid biosynthesis in plants. Annual review of plant biology. 2012;63:73–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheoran N, et al. Genetic analysis of plant endophytic Pseudomonas putida BP25 and chemo-profiling of its antimicrobial volatile organic compounds. Microbiological research. 2015;173:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tohge T, Watanabe M, Hoefgen R, Fernie AR. Shikimate and phenylalanine biosynthesis in the green lineage. Frontiers in plant science. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lahrmann U, et al. Host-related metabolic cues affect colonization strategies of a root endophyte. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:13965–13970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301653110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feijo JA, Costa SS, Prado AM, Becker JD, Certal AC. Signalling by tips. Current opinion in plant biology. 2004;7:589–598. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma H. Plant reproduction: GABA gradient, guidance and growth. Current biology: CB. 2003;13:R834–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouche N, Fromm H. GABA in plants: just a metabolite? Trends in plant science. 2004;9:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark SM, et al. Biochemical characterization, mitochondrial localization, expression, and potential functions for an Arabidopsis gamma-aminobutyrate transaminase that utilizes both pyruvate and glyoxylate. Journal of experimental botany. 2009;60:1743–1757. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ludewig F, Huser A, Fromm H, Beauclair L, Bouche N. Mutants of GABA transaminase (POP2) suppress the severe phenotype of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (ssadh) mutants in Arabidopsis. PloS one. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breitkreuz KE, Shelp BJ. Subcellular Compartmentation of the 4-Aminobutyrate Shunt in Protoplasts from Developing Soybean Cotyledons. Plant physiology. 1995;108:99–103. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Busch KB, Fromm H. Plant succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase. Cloning, purification, localization in mitochondria, and regulation by adenine nucleotides. Plant physiology. 1999;121:589–597. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamsai J, Siegrist J, Buchenauer H. Mode of action of the resistance-inducing 3-aminobutyric acid in tomato roots against Fusarium wilt. Z Pflanzenk Pflanzen. 2004;111:273–291. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li JJ, ZingenSell I, Buchenauer H. Induction of resistance of cotton plants to Verticillium wilt and of tomato plants to Fusarium wilt by 3-aminobutyric acid and methyl jasmonate. Z Pflanzenk Pflanzen. 1996;103:288–299. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu CC, Singh P, Chen MC, Zimmerli L. L-Glutamine inhibits beta-aminobutyric acid-induced stress resistance and priming in Arabidopsis. Journal of experimental botany. 2010;61:995–1002. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macho AP, Boutrot F, Rathjen JP, Zipfel C. Aspartate oxidase plays an important role in Arabidopsis stomatal immunity. Plant physiology. 2012;159:1845–1856. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.199810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kasahara H, et al. Distinct isoprenoid origins of cis- and trans-zeatin biosyntheses in Arabidopsis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:14049–14054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veach YK, et al. O-glucosylation of cis-zeatin in maize. Characterization of genes, enzymes, and endogenous cytokinins. Plant physiology. 2003;131:1374–1380. doi: 10.1104/pp.017210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vahabi, K. et al. The interaction of Arabidopsis with Piriformospora indica shifts from initial transient stress induced by fungus-released chemical mediators to a mutualistic interaction after physical contact of the two symbionts. BMC plant biology15, 58 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Vadassery J, et al. The role of auxins and cytokinins in the mutualistic interaction between Arabidopsis and Piriformospora indica. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI. 2008;21:1371–1383. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-10-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Falcone DL, Ogas JP, Somerville CR. Regulation of membrane fatty acid composition by temperature in mutants of Arabidopsis with alterations in membrane lipid composition. Bmc Plant Biol. 2004;4 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu XZ, Huang BR. Changes in fatty acid composition and saturation in leaves and roots of creeping bentgrass exposed to high soil temperature. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2004;129:795–801. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams JP, Khan MU, Mitchell K, Johnson G. The Effect of Temperature on the Level and Biosynthesis of Unsaturated Fatty-Acids in Diacylglycerols of Brassica-Napus Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1988;87:904–910. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.4.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hugly S, Kunst L, Browse J, Somerville C. Enhanced thermal tolerance of photosynthesis and altered chloroplast ultrastructure in a mutant of Arabidopsis deficient in lipid desaturation. Plant physiology. 1989;90:1134–1142. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.3.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kunst L, Browse J, Somerville C. Enhanced thermal tolerance in a mutant of Arabidopsis deficient in palmitic Acid unsaturation. Plant physiology. 1989;91:401–408. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.1.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chandra-Shekara AC, Venugopal SC, Barman SR, Kachroo A, Kachroo P. Plastidial fatty acid levels regulate resistance gene-dependent defense signaling in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:7277–7282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609259104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Savchenko T, et al. Arachidonic acid: an evolutionarily conserved signaling molecule modulates plant stress signaling networks. The Plant cell. 2010;22:3193–3205. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.073858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heil M, Baldwin IT. Fitness costs of induced resistance: emerging experimental support for a slippery concept. Trends in plant science. 2002;7:61–67. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Erb M, Meldau S, Howe GA. Role of phytohormones in insect-specific plant reactions. Trends in plant science. 2012;17:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun CA, et al. Piriformospora indica confers drought tolerance in Chinese cabbage leaves by stimulating antioxidant enzymes, the expression of drought-related genes and the plastid-localized CAS protein. J Plant Physiol. 2010;167:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murashige T, Skoog F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol Plantarum. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peškan-Berghöfer T, et al. Association of Piriformospora indica with Arabidopsis thaliana roots represents a novel system to study beneficial plant–microbe interactions and involves early plant protein modifications in the endoplasmic reticulum and at the plasma membrane. Physiologia Plantarum. 2004;122:465–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2004.00424.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verma S, et al. Piriformospora indica, gen. et sp. nov., a new root-colonizing fungus. Mycologia. 1998;90:896–903. doi: 10.2307/3761331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Darko E, Heydarizadeh P, Schoefs B, Sabzalian MR. Photosynthesis under artificial light: the shift in primary and secondary metabolism. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2014;369 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gobel C, Feussner I. Methods for the analysis of oxylipins in plants. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:1485–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Planchet E, Kaiser WM. Nitric oxide (NO) detection by DAF fluorescence and chemiluminescence: a comparison using abiotic and biotic NO sources. Journal of experimental botany. 2006;57:3043–3055. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.