ABSTRACT

The lack of new antibiotics has prompted investigation of the combination of two existing agents—cefepime, a broad-spectrum cephalosporin, and tazobactam—to broaden their efficacy against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae. We determined the pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of the combination in a murine neutropenic thigh model in order to establish its exposure-response relationships (ERRs). The PK of cefepime were determined for five doses; that of tazobactam was determined in earlier studies (Melchers et al., Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3373–3376, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.04402-14). The PK were linear for both compounds. The estimated mean (standard deviation [SD]) half-life of cefepime was 0.33 (0.12) h, and that of tazobactam was 0.176 (0.026) h; the volumes of distribution (V) were 0.73 liters/kg and 1.14 liters/kg, respectively. PD studies of cefepime administered every 2 h (q2h) with or without tazobactam, including dose fractionation studies of tazobactam, were performed against six ESBL-producing isolates. A sigmoidal maximum-effect (Emax) model was fitted to the data. In the dose fractionation study, the q2h regimen was more efficacious than the q4h and q6h regimens, indicating time-dependent activity of tazobactam. The threshold concentration (CT) best correlating with tazobactam efficacy was 0.25 mg/liter, as evidenced by the best fit of the percentage of time above the threshold concentration (%fT>CT) and response. A mean %fT>CT of 24.6% (range, 11.4 to 36.3%) for a CT of 0.25 mg/liter was required to obtain a bacteriostatic effect. We conclude that tazobactam enhanced the effect of cefepime in otherwise resistant isolates of Enterobacteriaceae and that the %fT>CT of 0.25 mg/liter best correlated with efficacy. These studies provide the basis for the development of human dosing regimens for this combination.

KEYWORDS: cefepime, beta-lactamase inhibitor, tazobactam

INTRODUCTION

The rapid and ongoing spread of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria throughout health care institutions is considered a critical medical and public health issue. The lack of development of new antibiotics active against these multidrug-resistant pathogens has further complicated the therapeutic dilemma. Alternatively, a combination of existing compounds, e.g., two antibiotics or an antibiotic and a nonantibiotic drug, might be a promising approach to effective therapies. Although comparative studies of several cephalosporins combined with an inhibitor (1–6) have been performed in vitro and in vivo, the feasibility of the combination of cefepime and tazobactam in vivo has not yet been fully examined. Studies in vitro have shown that cefepime MICs for resistant strains were drastically reduced in the presence of tazobactam and that thus, the strains became susceptible (7).

Therefore, in this study, we explore and corroborate the exposure-response relationships (ERRs) over 24 h of cefepime alone and of cefepime in combination with tazobactam, using several clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates in the well-established neutropenic thigh infection model (8, 9). The isolates harbor different extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes and exhibit various MICs for cefepime that are dependent on the tazobactam concentration in vitro.

It has already been established by earlier studies that for cephalosporins (as for all beta-lactams), it is the cumulative percentage of a 24-h dosing period during which free-drug concentration exceeds the MIC (%fTMIC) that is correlated with outcome (10–12). Therefore, following the strategy of our earlier studies with other beta-lactam–beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations, we used only one dosing regimen of cefepime to determine the exact dose of cefepime that was needed to obtain certain effects, such as a bacteriostatic effect or a 1- or 2-log10 kill (16, 17, 19).

The exposure-response relationships of tazobactam were subsequently investigated using different dosing regimens and dose intervals of tazobactam combined with a relatively low fixed dose of cefepime, corresponding to an exposure that was not effective for monotherapy over 24 h, due to the presence of ESBLs.

(This study was presented in part as posters at the 14th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Barcelona, Spain, 10 to 13 May 2014 [13], and the 54th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Washington, DC, 5 to 9 September 2014 [14].)

RESULTS

In vitro studies.

The results of the checkerboard experiments are shown in Table 1. As expected, tazobactam alone showed no antibacterial activity (15). Low concentrations of the inhibitor did not change the MIC of cefepime. However, increasing concentrations from 0.25 mg/liter onward showed increasing effects until a plateau was reached. The concentration at which no further change in the MIC was observed differed for every isolate.

TABLE 1.

Phenotype (MIC), beta-lactamase genotype, and pharmacodynamic characteristics of the isolates used in the experiments

| Isolate | Resistance summary | MIC (mg/liter) of FEPa combined with the following concn of tazobactam (mg/liter): |

FEP %fTMIC for a static effect | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | |||

| E. coli | |||||||||||||

| 5 | CTX-M-9, OXA-1 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.6 |

| 56 | CTX-M-15, TEM-1 | >32 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0 |

| 82 | CTX-M-14, TEM-1 | >32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | <28.8 |

| K. pneumoniae | |||||||||||||

| 58 | TEM-84, SHV-11 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 37.7 |

| 74 | CTX-M-1 | >32 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.064 | 0.125 | 0 |

| E. cloacae 27 | CTX-M-39, inducible AmpC | >32 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 |

FEP, cefepime.

PK of cefepime and tazobactam.

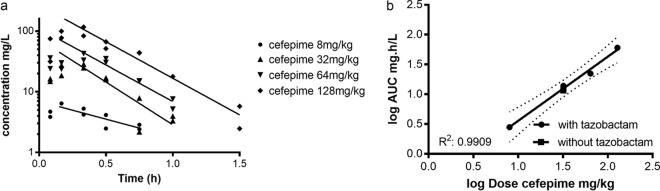

For all doses, the concentrations of cefepime were below the lower limit of quantitation (LLQ) at time points 2 and 3 h. The dose of 2 mg of cefepime/kg of body weight was excluded from pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis because all concentrations were below the LLQ. Plasma concentration-time curves were best described by a one-compartment model with first-order input and output. The pharmacokinetics of both compounds in plasma appear to be log linear and dose proportional. Figure 1a shows the concentration-time curves of cefepime (in the presence of tazobactam) for four doses (8, 32, 64, and 128 mg/kg). There was no significant difference in the terminal elimination rate between doses, as determined from the slope of the fits (P = 0.26). Likewise, the fit of the curve of the 32-mg/kg cefepime dose without tazobactam was not significantly different from that with tazobactam, and therefore no further doses of cefepime alone were investigated. The dose proportionality of cefepime in plasma is also demonstrated in Fig. 1b. The log area under the concentration-time curve [log (AUC)] is linearly related to the log dose, with an R2 of 0.99. Only one concentration-time curve was performed for cefepime without tazobactam (Fig. 1b, square). The overall relationship of the pooled results can be described by the following equation: log(AUC) = −1.039 + [1.077 × log(dose of cefepime)].

FIG 1.

(a) Concentration-time profiles of 4 different single doses of cefepime (8, 32, 64, and 128 mg/kg) in plasma from neutropenic mice whose thighs were infected. Doses of cefepime were coadministered with 32 mg/kg tazobactam. (b) Dose proportionality of cefepime in the plasma of infected mice after a single dose. Single doses were administered subcutaneously. AUC, area under the concentration-time curve. Dotted lines indicate the 95% confidence interval.

The estimated mean (standard deviation [SD]) half-life of cefepime was 0.33 (0.12) h, and the V was 0.73 liters/kg.

PD of cefepime alone.

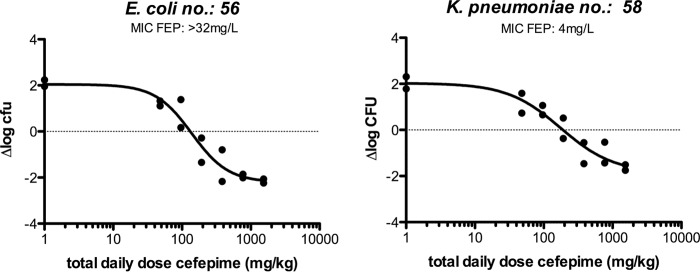

The in vivo efficacy of cefepime was determined for all six isolates studied. The magnitude of the PK/pharmacodynamic (PD) index (PDI) %TMIC (the percentage of the dosing interval during which the drug concentration exceeded the MIC) for a static effect of cefepime monotherapy ranged from 0 to 37.7% (Table 1). Only for one isolate (Escherichia coli 82) was a static effect not reached within the range of doses administered. Figure 2 shows two examples of the dose-response relationship of cefepime administered every 2 h (q2h). The percentages of the dosing interval during which free-drug concentrations were above the MIC (%fTMIC) were 0 and 37.7% for E. coli 56 and Klebsiella pneumoniae 58, respectively.

FIG 2.

Exposure-response relationships between the log10 daily dose of cefepime (FEP) (doses every 2 h) and Δlog CFU in the thighs for two strains. The %fTMIC corresponding to the static doses are 0% (left) and 37.7% (right).

Dose fractionation studies to determine the PK/PD index of tazobactam that best predicts efficacy.

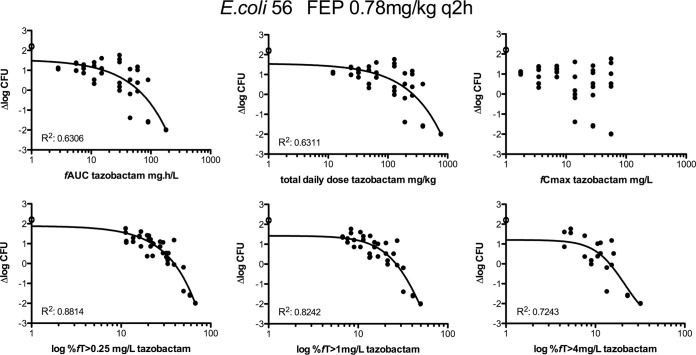

E. coli isolate 56 and K. pneumoniae isolate 58 were chosen initially to evaluate the exposure-response relationships of tazobactam combined with cefepime. To identify the pharmacodynamic parameters or indices that might best predict efficacy, groups of 2 mice were treated with different dosage regimens. Doses of tazobactam corresponding to different total daily doses (TDD), from 12 to 768 mg/kg, and with different frequencies of administration—12, 8, 6, 4, and 2 times daily (q2h, q3h, q4h, q6h, and q12h, respectively)—were evaluated together with a 0.78-mg/kg q2h cefepime dosing regime (a cefepime exposure corresponding approximately to a 2-log increase over the initial inoculum at time zero). The relationships of bacterial density (expressed as the change in log10 CFU [Δlog10 CFU] per thigh) with each of the three pharmacokinetic parameters and pharmacodynamic index (the peak concentration of free drug observed in plasma after its administration [fCmax], the cumulative percentage that free-drug concentrations are above the threshold concentration over a period of 24 h [%fT>CT], and the area under the free-drug concentration-time curve over 24 h [fAUC]) and with the total daily dose are shown in Fig. 3 for E. coli strain 56 as an example. The pharmacodynamic index that best correlated with tazobactam efficacy for both isolates appears to be the %fT>CT. In a separate analysis, the results indicated that q2h administration of tazobactam was more efficacious than q4h or q6h administration, since the effect curve of the q2h dosing regimen was shifted to the left (Fig. 4).

FIG 3.

Dose-response relationships for tazobactam, as determined by dose fractionation experiments, in mice infected in the thighs with E. coli isolate 56. Fixed doses of cefepime were coadministered q2h. The logarithmic scale of the x axis starts at 1. R2 is noted in the left bottom corner of each graph where a curve could be fitted. Open circles represent data for controls without tazobactam.

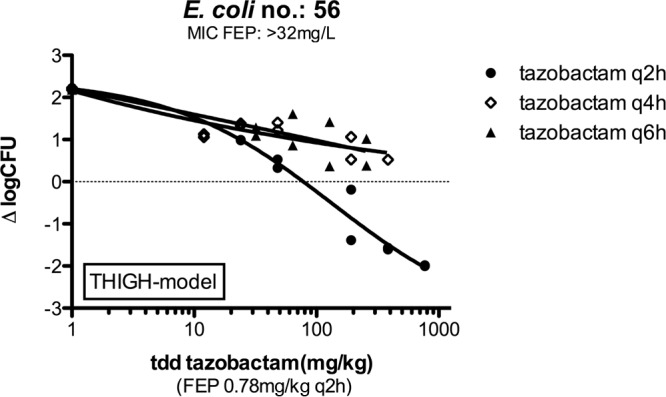

FIG 4.

Exposure-response relationships, as determined by dose fractionation studies, for q2h, q4h, and q6h tazobactam regimes against E. coli isolate 56. Cefepime was coadministered at 0.78 mg/kg q2h. tdd, total daily dose; FEP, cefepime.

Determination of the CT for tazobactam.

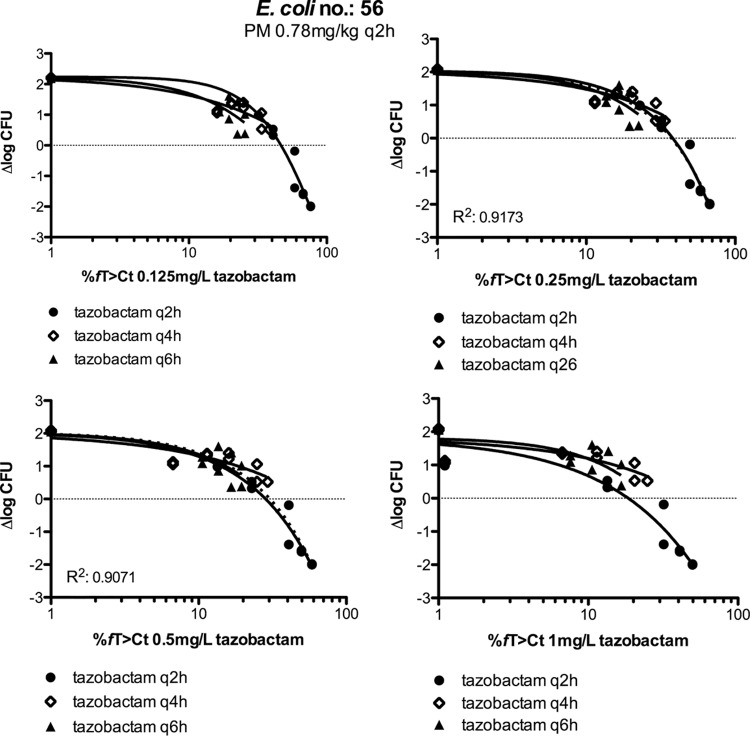

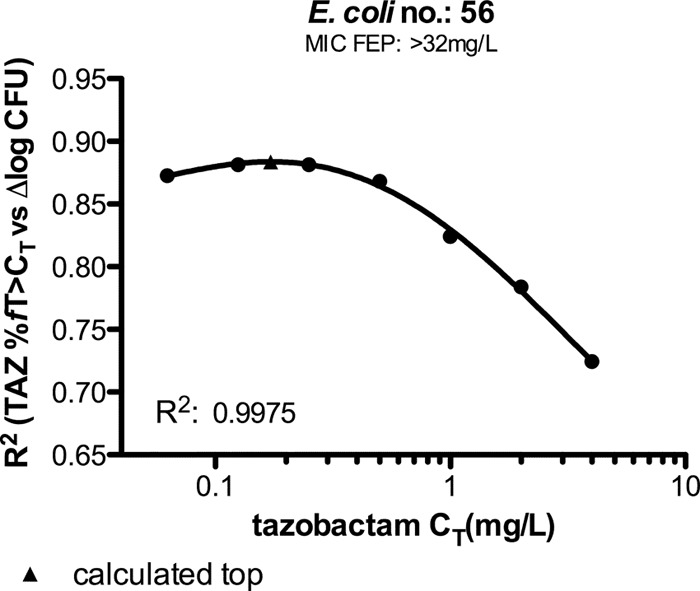

To determine which threshold concentration (CT) best correlated with efficacy, we used several approaches as described previously (16). The first approach was to determine the relationship between exposure and efficacy for a range of threshold levels and by visual inspection to decide which looked best. Upon visual inspection of the graphs of %fT>CT against Δlog CFU (using concentration thresholds of 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg/liter), 0.25 mg/liter appeared to be the best threshold value. To quantify these relationships, the R2 for each of the plots was plotted against the concentration threshold value, and a fourth-order polynomial was fitted to the data points to allow calculation of the optimum value. An example is shown in Fig. 5 for E. coli strain 56. The maxima of the best-calculated fits—representing the CT—for E. coli 56 and K. pneumoniae 58 were 0.17 mg/liter (R2, 0.88) and 0.27 mg/liter (R2, 0.69), respectively. The mean %fT>CT for these strains was 38.0% (SD, 6.9%) using these threshold values (as determined by the combination of tazobactam with a 0.78-mg/kg cefepime q2h regimen).

FIG 5.

Relationship between R2 of graphs, tazobactam (TAZ) %fT>CT against ∆log CFU, and tazobactam threshold (concentration thresholds of 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4) for E. coli 56. The filled triangle marks the top of the curve.

The second approach was to compare the q2h, q4h, and q6h dosing regimens, an approach we used previously when tazobactam was combined with ceftolozane (16). If CT is indeed the PK/PD index that best predicts efficacy, there should be a CT at which the %fT>CT–response relationships of the q2h, q4h, and q6h regimens do not differ significantly from each other. We therefore compared the best-fit curves of the %fT>CT with a range of CT values for the q2h, q4h, and q6h dosing regimens and determined whether the curves were or were not significantly different for each CT. Figure 6 shows an example for E. coli 56, indicating that for this strain, the optimum CT is between 0.25 and 0.5 mg/liter. R2 was slightly higher for a CT of 0.25 mg/liter than for a CT of 0.5 mg/liter when %fT>CT was plotted against Δlog CFU by combining q2h, q4h, and q6h data (dotted line). For K. pneumoniae 58, the optimum CT was 0.25 mg/liter.

FIG 6.

Relationships of the tazobactam %fT>CT with Δlog CFU for the q2h, q4h, and q6h regimes in experiments using mice whose thighs were infected with E. coli isolate 56. Top and bottom were shared for all data sets (q2h, q4h, and q6h curves) in each graph. Fixed doses of cefepime were coadministered q2h. R2 values pertain to the intersections of the dotted lines with the curves.

Further characterization of %fT>CT.

The efficacy of tazobactam was studied further with four other strains (isolates 5, 27, 58, and 82) and the two strains studied in the dose fractionation study in order to further quantify the relationship between the tazobactam concentration and the effect. Because the dose fractionation studies had indicated that the PK/PD index that best correlated with outcome was %fT>CT, tazobactam doses at a fixed dosing regimen were coadministered with 1 mg/kg cefepime q2h. The exposure (%fT>CT)-response relationship (ERR) was subsequently determined for each strain for seven tazobactam thresholds between 0.0625 and 4 mg/liter. The %fT>CT values of tazobactam associated with bacterial stasis are shown in Table 2 for five of the seven different tazobactam thresholds. Subsequently, the R2 of each of the seven ERRs was plotted for the corresponding CT as described in the preceding paragraph (an example is shown in Fig. 5). The calculated CT with the highest R2 was subsequently used as the tazobactam threshold for each strain. The mean CT corresponding to the highest R2 for the 6 strains was 0.25 mg/liter (SD, 0.1 mg/liter). The mean %fT>CT was 23.4% (SD, 10.4%). Alternatively, a fixed CT of 0.25 mg of tazobactam/liter was used to determine the %fT>CT for each strain. This resulted in a range of %fT>CT values required for a static effect from 11.4% to 36.3% (mean, 24.6%; SD, 9.2%). For a 1-log10 kill (which was not achieved for 2 isolates, E. cloacae 27 and K. pneumoniae 74), the required %fT>CT was 16.5% to 54.0% (mean, 39.7%; SD, 16.6%). The R2 values for the ERR for the 0.25-mg/liter threshold concentration of tazobactam were 0.91, 0.73, and 0.92 for E. coli isolates 5, 56, and 82, respectively; 0.93 and 0.98 for K. pneumoniae isolates 58 and 74, respectively; and 0.49 for E. cloacae isolate 27.

TABLE 2.

Static doses and %fT>CT of tazobactam in q2h dosing regimens for 6 isolatesa

| Isolate | FEP MIC (mg/liter) | FEP dose (mg/kg) | TDD of TZB (mg/kg) for a static effect | %fT>CTb for a TZB CT (mg/liter) of: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| E. coli | ||||||||

| 5 | 8 | 1 | 9.6 | 20.3 | 11.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 56 | >32 | 1 | 24.4 | 32.2 | 23.3 | 14.3 | 4.9 | 0.0 |

| 82 | >32 | 1 | 67.6 | 45.2 | 36.3 | 27.4 | 18.2 | 9.1 |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||||||

| 58 | 4 | 1 | 44.1 | 39.7 | 30.8 | 21.9 | 12.6 | 3.5 |

| 74 | >32 | 1 | 15.1 | 26.0 | 17.1 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| E. cloacae 27 | >32 | 1 | 37.7 | 37.7 | 28.8 | 19.9 | 10.6 | 1.4 |

FEP, cefepime; TZB, tazobactam.

The mean (SD) %fT>CT was 33.5% (9.2%) for a tazobactam CT of 0.125 mg/liter, 24.6% (9.2%) for 0.25 mg/liter, and 15.6% (9.3%) for 0.5 mg/liter.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used various tazobactam doses combined with a suboptimal cefepime therapeutic dose in order to determine the PK/PD of tazobactam in a murine neutropenic thigh infection model. Tazobactam increased the effectiveness of cefepime in vitro as well as in vivo against otherwise cefepime resistant strains. In findings comparable to those for avibactam and similar to those in our study with ceftolozane and tazobactam (16, 17), %fT>CT was the most predictive PD index for describing the exposure-response relationship of tazobactam. There did not appear to be a relationship between peak tazobactam concentrations (Cmax), AUC, or total daily dose (TDD) and efficacy. In the dose fractionation experiments in this study, the best exposure-response fit was obtained using %fT>CT at a CT of approximately 0.25 mg/liter.

The half-lives of cefepime and tazobactam were relatively similar in mice, in accordance with the literature (18), and therefore, we were able to coadminister the compounds.

It is well known that the most important driver determining the in vivo efficacy of a beta-lactam antibiotic is the time above the MIC. For a static effect, the %fTMIC is 35% to 40% for cephalosporins (10), and higher exposures are generally required for 1- and 2-log kills. However, in the present study, we found several isolates for which this value was much lower, even as low as 0%. In earlier studies, we and other groups observed this phenomenon as well (17, 19–21). Extensive discussions about this have been well described by Berkhout et al. (17) and MacVane et al. (30), who gave several possible reasons, such as differences in growth and kill rates in vivo. The affinity of the drug combined with the number of receptors might play an important role as well, since these are different in vitro and in vivo. For the future, it might be worthwhile to look into these possibilities, especially because 2 of the isolates (K. pneumoniae 58 and 74) were also used in our ceftolozane-tazobactam study (16). Using the same murine models, a higher %fTMIC for a static effect was found for ceftolozane than for cefepime in this study. Therefore, we used cefepime exposures corresponding to approximately 2-log regrowth and a %fTMIC value of 0%—exposures ineffective as monotherapy—for most experiments in order to identify the PK/PD index for tazobactam.

Vanscoy et al. proposed a tazobactam CT of 0.5 times the MIC of ceftolozane-tazobactam (determined with a tazobactam concentration of 4 mg/liter) for the %T>CT of tazobactam as the best predictor of the efficacy of the ceftolozane-tazobactam combination in their hollow-fiber model studies (22). The authors based this relationship on pooled data from the %T>CT and the change in log10 CFU from baseline at 24 h that gave a high R2 value. Using the same approach for cefepime-tazobactam, we determined the fits for 0.5× MIC and other MIC reference values (1× MIC, 0.25× MIC [results not shown]). Of the MIC multiples we investigated, 0.5× MIC did indeed provide the best results in that the measure of error of %fT>CT was the lowest, although the differences were marginal. However, if the value of R2 is taken as a reference for the best fit, the threshold value provided an even better fit for E. coli. Since the 0.5× MIC values were systematically lower than the CT values that we observed, the mean %fT>CT for the 0.5× MIC value that resulted in a static effect was somewhat higher in the study of Vanscoy et al. (36.6%) than in our study (24.6%). Another observation with Vanscoy's proposal is the variation in effect above static tazobactam levels. When a line was fitted to the data points representing the tazobactam %fT>CT and the change in log10 CFU from baseline at 24 h for the pooled data across all isolates, a low R2 (approximately 0.5) was obtained. Remarkably, the curve fits for the individual strains are quite good, with high R2 values, and the static effects are very similar for all strains, because almost all the curve fits from individual isolates crossed the static line at the same value. This might also be affected by the differences in %fTMIC in vivo for cefepime between the isolates, considering that the MIC is used as a hybrid parameter.

Previous studies suggested that once the CT of the inhibitor was achieved, the pharmacodynamic effects of the combination were fully predicted by the initial parent drug (23–26). Thus, another approach to validating the CT could be to assume that a %fTMIC of 30 to 40% is required for cefepime efficacy, to use the MIC from the in vitro checkerboards to find the tazobactam concentration needed for the corresponding MIC of cefepime, and subsequently to determine the %fT>CT for that specific concentration. This approach was also used for relebactam (27) and in our earlier study with ceftolozane (16). The mean %fT>CT for tazobactam required for stasis using this method was 4% (SD, 5.9%; range, 0 to 14.3%), far lower than the value we found for ceftolozane-tazobactam. A possible explanation could be the low %fTMIC of cefepime in vivo for a static effect and therefore an overestimation of the tazobactam CT. For instance, if we recalculate using 0.25× CT, the mean %fT>CT is 22% (SD, 6.5%), which is closer to our original findings. It would be prudent not to use this method for cefepime until we can fully explain our findings. It might be of interest to repeat part of the study with more isolates showing a %fTMIC for cefepime of >30% in order to see if there is any change in the %fT>CT for tazobactam using this particular approach.

Although tazobactam improved the efficacy of cefepime in all species, and a sigmoid dose-response curve could be fitted for all strains, the decrease in CFU was generally greater for the E. coli isolates. Even with the highest doses of tazobactam, a 1-log kill (from the initial inoculum [t = 0]) was not reached for two isolates (E. cloacae 27 and K. pneumoniae 74) over 24 h. This could have been due to the relatively low dose of cefepime used in these experiments. Alternatively, we often observe less kill for K. pneumoniae than for E. coli, even at maximum exposures.

We conclude that the effect of tazobactam was dependent on the dose frequency: a decreased effect was observed with decreased frequency. The main PK/PD index correlated with effect was the time above the concentration threshold of tazobactam (0.25 mg/liter), and the magnitudes were 24.6% (SD, 9.2%) and 39.7% (SD, 16.6%) for a static effect and 1-log kill, respectively. These values are comparable to those from the ceftolozane-tazobactam study (16) using a tazobactam CT of 0.5 mg/liter: 28.2% (SD, 11.9%) and 44.4% (SD, 10.9%).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs.

Cefepime (Maxipime; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company) and tazobactam (Molekula Deutschland Limited, Germany) were obtained commercially. Drugs were reconstituted in normal sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) to a concentration of 100 mg/ml. Solutions were stored at −80°C until use. Subsequently, they were combined and/or diluted to the final concentrations needed for the experiments.

Strains.

Three Escherichia coli isolates (isolates 5, 56, and 82) two Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates (isolates 58 and 74), and one Enterobacter cloacae isolate (isolate 27) with various MICs and beta-lactamase expression were used for the PK/PD experiments (Table 1). Isolates were selected from a private clinical ESBL collection on the basis of their resistance to cefepime, alone and combined with tazobactam, and of harboring ESBL genes.

In vitro susceptibility testing.

Isolates were tested for susceptibility to cefepime alone and in combination with tazobactam by broth microdilution using the ISO (International Organization for Standardization) guidelines (NEN-EN-ISO 20776-1:2006). Checkerboard experiments were performed to explore interactions using doubling dilutions over the final range of 0.016 to 32 mg/liter cefepime and 0.031 to 16 mg/liter tazobactam. Microtiter trays were prepared in-house using the compounds described above in freshly prepared Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth (Difco batch no. 9106707; Brunschwig Chemie, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Every tray contained a negative and a positive growth control. Subsequently, they were stored at −80°C until use. On the day of the experiment, trays were thawed, inoculated with a bacterial suspension to a final concentration of 0.5 × 105 CFU/ml, and incubated at 37°C in ambient air. After 18 to 20 h, MICs were read manually, using an angled mirror with a support stand, as the lowest concentration of cefepime that completely inhibited visible growth. Each set of MIC determinations included three control strains: Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603.

Setting and animals.

All animal experiments were carried out in the Central Animal Facility (“Centraal Dierenlab”) at Radboudumc Nijmegen and were conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the European Community (directive 2010/63/EU 22, September 2010). Studies were approved by the animal welfare committee of Radboud University (approval no. RU-DEC 2012-181). Outbred female CD-1 mice obtained from Charles River, The Netherlands, weighing 18 to 22 g on arrival, were used in the experiments. The animals were allowed to acclimatize for at least 5 days upon arrival and received food and water ad libitum. The mice were rendered neutropenic by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of cyclophosphamide on days −4 (150 mg/kg) and −1 (100 mg/kg) prior to infection (28).

Infection.

On the day of the experiment, animals were infected with an inoculum of approximately 2 × 106 to 3 × 106 bacteria per thigh. The inoculum was prepared by standard procedures as described previously (19). Briefly, 50 ml fresh Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth was inoculated with several colonies from a 24-h blood-agar plate, which were allowed to grow to a final concentration of 108 to 109 bacteria per ml. The batch was divided over 25 microtubes and was stored at −80°C. Subsequently, growth curves were prepared on separate days to determine the inoculum and reproducibility after thawing. On the day of infection, 0.5 ml was taken from the freezer and was added to 4.5 ml prewarmed MH broth. After incubation for 1 h, this solution was diluted to a final inoculum of approximately 5 × 107 CFU/ml. Two different isolates with distinct phenotypic appearances were simultaneously injected intramuscularly (0.05 ml) into opposite thighs.

PK studies.

The single-dose pharmacokinetics (PK) of cefepime were determined for doses of 2, 8, 32, 64, and 128 mg/kg cefepime combined with 32 mg/kg tazobactam and for 32 mg/kg cefepime alone. Drugs were administered subcutaneously (0.1 ml) 2 h after thighs were infected with K. pneumoniae 58 and E. coli 5 (one isolate per thigh). Blood was collected in 1-ml K3 EDTA tubes through orbital sinus bleeding under isoflurane sedation, and subsequently the mice were killed through cervical dislocation. Time points were as follows: before administration (t = 0 h); 0.083, 0.167, 0.333, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, and 2 min after administration; and 3 h after administration. One sample was taken per mouse, and every time point was sampled in duplicate (2 mice). Blood samples were centrifuged immediately in a precooled centrifuge, and plasma samples were stored at −80°C until concentrations were determined. Concentrations were determined in a separate facility (Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands). Plasma cefepime concentrations were determined by a validated high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method with UV detection (255 nm), with a lower limit of quantitation (LLQ) of 2 ng/ml. Tazobactam pharmacokinetics have been studied extensively previously (29). The PK analysis was performed using noncompartmental modeling in GraphPad Prism, version 5.0, and WinNonlin, version 2.1 (Pharsight Corp., St. Louis, MO). The AUC was obtained using the log-linear trapezoidal rule from the pooled data set for each curve (n, 2 to 4 per data point). Protein binding levels in plasma of 25.1% (standard error [SE], 2.45%) for tazobactam (29) and 20% for cefepime (5) were used in the PK simulations to determine the PDI for each dosing regimen and strain.

PD studies.

For the pharmacodynamic (PD) studies, mice were treated either with cefepime, alone or in combination with tazobactam, or with a sham control (saline) at the beginning of treatment and every 2 h thereafter for 24 h. Cefepime was administered as monotherapy q2h in 2-fold-increasing doses, ranging from 2 to 64 mg/kg or from 4 to 128 mg/kg, corresponding to a %fTMIC of 0% for the lowest and 86.6% for the highest dose.

Full-dose fractionation studies of tazobactam were performed for 2 isolates (E. coli 56 and K. pneumoniae 74) using the approach described previously (16, 17, 19). Cefepime, at exposures corresponding to approximately 2-log10 growth (after 24 h) over the initial inoculum (t = 0), was coadministered q2h with tazobactam doses in increasing doses (range, 2 to 64 mg/kg) at various frequencies (2, 4, 6, and 12 times/24 h). An additional 4 isolates (E. coli 5 and 82, K. pneumoniae 58, E. cloacae 27) were tested for further estimation of the pharmacodynamic indices, using increasing doses of tazobactam during a q2h 1-mg/kg cefepime regime (approximately 2-log10 growth over the initial inoculum). Control experiments with cefepime alone were conducted for all strains to verify a ∼2-log increase in the bacterial burden, including a sham control (data not shown).

Sampling and analysis.

All dosing regimens were performed with at least two animals. At 0 h, 2 mice were humanely sacrificed to determine the initial inoculum just before treatment. All other animals were sacrificed at 24 h unless the welfare of the animals necessitated earlier termination, in accordance with animal welfare regulations. Excised thighs were transferred to a precooled 12-ml plastic tube (item no. 163275; Greiner) containing 2 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were homogenized using a T-25 Ultra-Turrax instrument. A 10-fold dilution series was prepared, and three 10-μl aliquots per dilution were plated onto a chromeID ESBL (bioMérieux) plate. The following day, colonies were counted and the number of CFU calculated. The drug effect was determined as the difference between the log10 CFU values at 24 h and 0 h (mean value for 2 mice), expressed as Δlog CFU. The limit of detection was ≤1.82 log CFU/ml. Free-drug concentrations were used in all calculations, using protein binding levels of 20% and 25.1% for cefepime and tazobactam, respectively. The estimated mean (SD) half-life of tazobactam used was 0.176 (0.026) h, and the V was 1.14 liters/kg. The Emax model (or linear regression) was fit to the dose and PDI responses to determine the PDI values of cefepime, alone and in combination with tazobactam, resulting in a static effect. For tazobactam, the percentages of the dosing interval above the threshold concentration (%fT>CT) were calculated for CT values (virtual in vivo inhibitory concentrations) of 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg/liter.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Roger Brüggemann, a clinical pharmacologist at the Radboud University Medical Center, for critical discussions and support.

This study was funded by the Department of Microbiology of the Radboud University Medical Center.

J.W.M. has received research funding from Adenium, Astra-Zeneca, Basilea Pharmaceutica International Ltd., Cubist, Eumedica, Merck & Co., Pfizer, Polyphor, Roche, Shionogi, and Wockhardt. The other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Ogtrop ML, Mattie H, Guiot HF, van Strijen E, Hazekamp-van Dokkum AM, van Furth R. 1990. Comparative study of the effects of four cephalosporins against Escherichia coli in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 34:1932–1937. doi: 10.1128/AAC.34.10.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattie H, Sekh BA, van Ogtrop ML, van Strijen E. 1992. Comparison of the antibacterial effects of cefepime and ceftazidime against Escherichia coli in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 36:2439–2443. doi: 10.1128/AAC.36.11.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fournier JL, Ramisse F, Jacolot AC, Szatanik M, Petitjean OJ, Alonso JM, Scavizzi MR. 1996. Assessment of two penicillins plus beta-lactamase inhibitors versus cefotaxime in treatment of murine Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40:325–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ju HS, Leung S, Brown B, Stringer MA, Leigh S, Scherrer C, Shepard K, Jenkins D, Knudsen J, Cannon R. 1997. Comparison of analytical performance and biological variability of three bone resorption assays. Clin Chem 43:1570–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knudsen JD, Fuursted K, Frimodt-Moller N, Espersen F. 1997. Comparison of the effect of cefepime with four cephalosporins against pneumococci with various susceptibilities to penicillin, in vitro and in the mouse peritonitis model. J Antimicrob Chemother 40:679–686. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sood S. 2013. Comparative evaluation of the in-vitro activity of six beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations against Gram negative bacilli. J Clin Diagn Res 7:224–228. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/4564.2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mouton J, Melchers M, van Mil A. 2010. In vitro activity of cefepime alone and in combination with tazobactam against ESBL producers. Abstr 50th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, poster E-809, p A-2251. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouton JW, van Ogtrop ML, Andes D, Craig WA. 1999. Use of pharmacodynamic indices to predict efficacy of combination therapy in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:2473–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buijs J, Dofferhoff AS, Mouton JW, van der Meer JW. 2007. Continuous administration of PBP-2- and PBP-3-specific beta-lactams causes higher cytokine responses in murine Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli sepsis. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:926–933. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig WA. 2003. Basic pharmacodynamics of antibacterials with clinical applications to the use of beta-lactams, glycopeptides, and linezolid. Infect Dis Clin North Am 17:479–501. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouton JW, Punt N, Vinks AA. 2007. Concentration-effect relationship of ceftazidime explains why the time above the MIC is 40 percent for a static effect in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3449–3451. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01586-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crandon JL, Nicolau DP. 2015. In vivo activities of simulated human doses of cefepime and cefepime-AAI101 against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2688–2694. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00033-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melchers MJ, van Mil AC, Lagarde C, Mouton JW. 2014. Pharmacodynamics of tazobactam combined with cefepime in a neutropenic mouse thigh model, poster P-1736 Fourteenth Eur Cong Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, Barcelona, Spain, 10 to 13 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melchers MJ, van Mil AC, Lagarde C, Mouton JW. 2014. Pharmacodynamic interaction between cefepime and tazobactam in a neutropenic mouse thigh model, poster A-1340 Abstr 54th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, Washington, DC, 5 to 9 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fass RJ, Prior RB. 1989. Comparative in vitro activities of piperacillin-tazobactam and ticarcillin-clavulanate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 33:1268–1274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.33.8.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melchers MJ, Mavridou E, van Mil AC, Lagarde C, Mouton JW. 2016. Pharmacodynamics of ceftolozane combined with tazobactam against Enterobacteriaceae in a neutropenic mouse thigh model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:7272–7279. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01580-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkhout J, Melchers MJ, van Mil AC, Seyedmousavi S, Lagarde CM, Schuck VJ, Nichols WW, Mouton JW. 2015. Pharmacodynamics of ceftazidime and avibactam in neutropenic mice with thigh or lung infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:368–375. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01269-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyazaki S, Okazaki K, Tsuji M, Yamaguchi K. 2004. Pharmacodynamics of S-3578, a novel cephem, in murine lung and systemic infection models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:378–383. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.2.378-383.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mavridou E, Melchers RJ, van Mil AC, Mangin E, Motyl MR, Mouton JW. 2015. Pharmacodynamics of imipenem in combination with beta-lactamase inhibitor MK7655 in a murine thigh model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:790–795. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03706-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maglio D, Ong C, Banevicius MA, Geng Q, Nightingale CH, Nicolau DP. 2004. Determination of the in vivo pharmacodynamic profile of cefepime against extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli at various inocula. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:1941–1947. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.1941-1947.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig WA, Andes DR. 2013. In vivo activities of ceftolozane, a new cephalosporin, with and without tazobactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae, including strains with extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, in the thighs of neutropenic mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1577–1582. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01590-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanscoy B, Mendes RE, McCauley J, Bhavnani SM, Bulik CC, Okusanya OO, Forrest A, Jones RN, Friedrich LV, Steenbergen JN, Ambrose PG. 2013. Pharmacological basis of beta-lactamase inhibitor therapeutics: tazobactam in combination with ceftolozane. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5924–5930. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00656-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dudley MN. 1995. Combination beta-lactam and beta-lactamase-inhibitor therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. Am J Health Syst Pharm 52:S23–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crandon JL, Schuck VJ, Banevicius MA, Beaudoin ME, Nichols WW, Tanudra MA, Nicolau DP. 2012. Comparative in vitro and in vivo efficacies of human simulated doses of ceftazidime and ceftazidime-avibactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:6137–6146. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00851-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crandon JL, Nicolau DP. 2013. Human simulated studies of aztreonam and aztreonam-avibactam to evaluate activity against challenging Gram-negative organisms, including metallo-beta-lactamase producers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3299–3306. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01989-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.VanScoy B, Mendes RE, Nicasio AM, Castanheira M, Bulik CC, Okusanya OO, Bhavnani SM, Forrest A, Jones RN, Friedrich LV, Steenbergen JN, Ambrose PG. 2013. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of tazobactam in combination with ceftolozane in an in vitro infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2809–2814. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02513-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mouton J, Mavridou M, Donnelly R, van Mil A. 2011. PK/PD of beta-lactam—beta-lactamase inhibitors: correlation of in vitro susceptibility testing with in vivo efficacy. Abstr 51st Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, abstr A-1687. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuluaga AF, Salazar BE, Rodriguez CA, Zapata AX, Agudelo M, Vesga O. 2006. Neutropenia induced in outbred mice by a simplified low-dose cyclophosphamide regimen: characterization and applicability to diverse experimental models of infectious diseases. BMC Infect Dis 6:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melchers MJ, Mavridou E, Seyedmousavi S, van Mil AC, Lagarde C, Mouton JW. 2015. Plasma and epithelial lining fluid pharmacokinetics of ceftolozane and tazobactam alone and in combination in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3373–3376. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04402-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacVane SH, Crandon JL, Nichols WW, Nicolau DP. 2014. Unexpected in vivo activity of ceftazidime alone and in combination with avibactam against New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a murine thigh infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7007–7009. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02662-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]