ABSTRACT

Bacillus anthracis is considered a likely agent to be used as a bioweapon, and the use of a strain resistant to the first-line antimicrobial treatments is a concern. We determined treatment efficacies against a ciprofloxacin-resistant strain of B. anthracis (Cipr Ames) in a murine inhalational anthrax model. Ten groups of 46 BALB/c mice were exposed by inhalation to 7 to 35 times the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of B. anthracis Cipr Ames spores. Commencing at 36 h postexposure, groups were administered intraperitoneal doses of sterile water for injections (SWI) and ciprofloxacin alone (control groups), or ciprofloxacin combined with two antimicrobials, including meropenem-linezolid, meropenem-clindamycin, meropenem-rifampin, meropenem-doxycycline, penicillin-linezolid, penicillin-doxycycline, rifampin-linezolid, and rifampin-clindamycin, at appropriate dosing intervals (6 or 12 h) for the respective antibiotics. Ten mice per group were treated for 14 days and observed until day 28. The remaining animals were euthanized every 6 to 12 h, and blood, lungs, and spleens were collected for lethal factor (LF) and/or bacterial load determinations. All combination groups showed significant survival over the SWI and ciprofloxacin controls: meropenem-linezolid (P = 0.004), meropenem-clindamycin (P = 0.005), meropenem-rifampin (P = 0.012), meropenem-doxycycline (P = 0.032), penicillin-doxycycline (P = 0.012), penicillin-linezolid (P = 0.026), rifampin-linezolid (P = 0.001), and rifampin-clindamycin (P = 0.032). In controls, blood, lung, and spleen bacterial counts increased to terminal endpoints. In combination treatment groups, blood and spleen bacterial counts showed low/no colonies after 24-h treatments. The LF fell below the detection limits for all combination groups yet remained elevated in control groups. Combinations with linezolid had the greatest inhibitory effect on mean LF levels.

KEYWORDS: ciprofloxacin, anthrax, multidrug therapy

INTRODUCTION

In the past, the naturally occurring and inducible resistance to penicillin in Bacillus anthracis led experts to suggest avoiding the use of penicillin and related β-lactam antibiotics for both postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) and the treatment of B. anthracis infections until susceptibilities are determined (1). Given these concerns, guidelines recommend a fluoroquinolone, such as ciprofloxacin or doxycycline, as the first-line drug for oral PEP following suspected B. anthracis spore aerosol exposure (1, 2). Based on its bactericidal action and superior central nervous system penetration, ciprofloxacin is recommended over doxycycline as the primary antimicrobial agent for the treatment of anthrax cases with systemic disease when meningitis has not or cannot be ruled out (3). In such patients, ciprofloxacin is recommended as one component of a multidrug combination that includes a second bactericidal agent and a protein synthesis inhibitor (1–3).

Ciprofloxacin is typically the first-line antimicrobial agent for treatment when anthrax is suspected. During an intentional release, 36 to 72 h may pass before susceptibility test results are available for isolates from index cases or environmental samples. In an event involving a B. anthracis ciprofloxacin-resistant or a multidrug-resistant (MDR) strain, the first cases are likely to present and be treated before drug susceptibility profiles are available. Therefore, the initial treatment may include one or more ineffective antimicrobials.

A delayed initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy significantly reduces survival in animal models (4, 5, 6) and appears to adversely impact outcomes in humans (7, 8). Although data are limited, regimens comprising multiple antimicrobials appear to offer survival advantages in both animals and humans (9, 10). Therefore, there is a demonstrated need to develop effective multidrug treatment strategies for early empirical treatment of anthrax or antibiotic-resistant anthrax. Furthermore, a variety of such strategies is desirable to address insufficient, scarce, or depleted first-line antimicrobials and to cover individuals with drug allergies and intolerances.

There are limited in vivo animal efficacy data and fewer human data on which to base combination therapies to treat anthrax. Animal model studies will help address this gap in data, and there may be benefits to first-line or potential alternative PEP agents which may only be evaluated in vivo (11, 12). As an example, the use of a protein synthesis inhibitor either alone or in addition to another antibiotic has long been suggested as a means to suppress anthrax toxin production (13).

In this study, we tested and evaluated the efficacy of various multidrug combinations of antimicrobial agents against inhalational anthrax resulting from aerosol exposure to a ciprofloxacin-resistant B. anthracis strain. The murine model data provide an evidence-based approach to inform (i) alternative antimicrobial agents for PEP and treatment of MDR anthrax, (ii) potential Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) acquisitions, and (iii) starting points for oral PEP efficacy and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies in nonhuman primates that would be required for FDA approval for PEP and treatment. This study addresses an important data gap and increases preparedness for bioterrorism events.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of the gyrA, gyrB, parE, and parC genes in the ciprofloxacin-resistant B. anthracis strain BACr4-2 showed a single mutation in the gyrA quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) representing a C254T change resulting in a S85L amino acid change in gyrase A, which has been observed previously in ciprofloxacin-resistant B. anthracis isolates (14, 15). The 50% lethal dose (LD50) determined for BACr4-2 was 2 × 104 CFU/whole body, and the mean time to death (MTD) was 55.5 h. This was in comparison to the parent strain LD50 of 3.4 × 104 CFU/whole body and an MTD of 78.5 h (16). Due to the shorter MTD with BACr4-2, the initiation of antimicrobial treatment was moved to 36 h postchallenge, compared with that of previous studies with the parent strain for which treatment typically started at 48 h postchallenge (5, 16, 17).

The target exposure for the study was 50 LD50s, but the actual range of exposure doses across the 9 aerosols was 7 to 32 LD50s per whole body (1.3 × 105 to 6.4 × 105 CFU/mouse). The distribution of animals into each experimental group (treatment and serial sampling) was equally balanced so that challenge dose variance would not be a factor among groups.

Table 1 compares the antibiotic susceptibilities of the BACr4-2 strain and the parent Ames strain for ciprofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, and several protein synthesis inhibitors. The BACr4-2 MIC values were elevated more than 10-fold over those of the parent Ames strain for the fluoroquinolones, the β-lactam penicillin G, and the protein synthesis inhibitor doxycycline. Of note, the MIC values for all three fluoroquinolones tested were elevated over those of the parent strain, with ciprofloxacin showing the largest change at 16 versus 0.125 μg/ml (128-fold). The MIC value for penicillin G was 16 versus 0.5 μg/ml and the MIC value for the protein synthesis (PS) inhibitor doxycycline was elevated 15-fold. It has been shown that B. anthracis possesses an inducible β-lactamase, and this most likely accounts for the observed elevated activity (18, 19). The doxycycline MIC, while elevated over that of the parent, is still well below the CLSI breakpoint of ≤1 μg/ml (20). MICs for all other antibiotics were either not increased (clindamycin) or marginally increased (2- to 4-fold). The MICs for ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin were unchanged in the presence of 10 μg/ml reserpine, indicating no active efflux.

TABLE 1.

Antibiotic susceptibilities

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) |

Ratio (BACr4-2 to Ames) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ames | BACr4-2 | ||

| Fluoroquinolones | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.125 | 16 | 128 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.125 | 2 | 16 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125 | 2 | 16 |

| Cell wall synthesis inhibitor (β-lactams or other) | |||

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.12 | 4.0 |

| Imipenem | 0.008 | 0.03 | 4 |

| Penicillin G | 0.5 | 16 | 32 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 0.125 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Vancomycin | 0.125 | 0.25 | 2.0 |

| Protein synthesis inhibitors | |||

| Linezolid | 2 | 4 | 2.0 |

| Clindamycin | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1.0 |

| Gentamicin | 0.5 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Doxycycline | 0.008 | 0.125 | 16 |

| Rifampin (mRNA) | 0.008 | 0.015 | 2 |

A two-pronged treatment strategy was employed to overcome ciprofloxacin resistance and improve outcomes. A β-lactam was substituted for the fluoroquinolone to provide bactericidal activity and a protein synthesis inhibitor was added to reduce toxin production. Meropenem was the preferred β-lactam in groups 1 to 4, which each included one of four PS inhibitors, namely, linezolid, clindamycin, rifampin, or doxycycline (Table 1). Penicillin G was also tested in combination with linezolid and doxycycline (groups 5 and 6). To test the efficacy without a β-lactam antimicrobial and to determine the benefit of blocking two different stages of protein synthesis, groups 7 and 8 were treated with rifampin-linezolid or rifampin-clindamycin combined with ciprofloxacin.

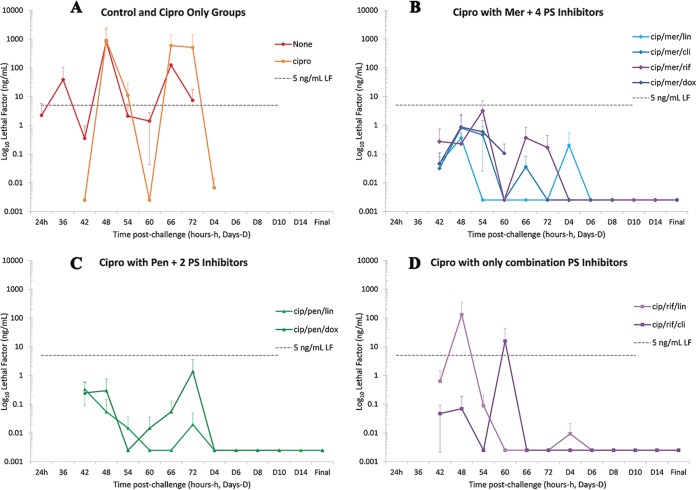

The efficacies of the various combinations as measured by survival are summarized in Fig. 1. The 2-PS-inhibitor rifampin-linezolid group had the highest survival, 100%, followed by the meropenem-linezolid group with 90% because of one late loss (at 22 days). The meropenem-doxycycline group had the lowest survival of any combination at 70%, with all three losses by 15 days. All antimicrobial agent combinations tested were significantly different from the no-treatment control group, sterile water for injections (SWI) (P < 0.0004), and each was significantly different from the ciprofloxacin control group: meropenem-linezolid (P = 0.004), meropenem-clindamycin (P = 0.005), meropenem-rifampin (P = 0.012), meropenem-doxycycline (P = 0.032), penicillin-linezolid (P = 0.026), penicillin-doxycycline (P = 0.012), rifampin-linezolid (P = 0.001), and rifampin-clindamycin (P = 0.032). There were no significant differences in survival between any of the antimicrobial agent treatment groups.

FIG 1.

Survival of mice exposed to ciprofloxacin-resistant B. anthracis Ames (BACr4-2) and treated with combination therapies, including ciprofloxacin beginning 36 h postexposure. Double arrow indicates duration of antibiotic therapy.

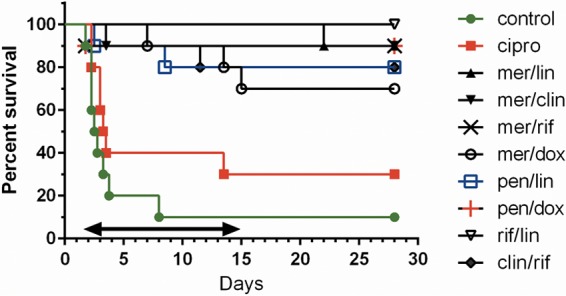

Culture results from blood, spleen, and lung samples from animals surviving to day 14 are shown in Fig. 2A, B, and C, respectively. Ciprofloxacin alone and the no-treatment control groups showed increased counts in blood and both tissues to 66 h, after which there were either no or an insufficient number of animals remaining to obtain further data. Culture levels in combination treatment groups quickly dropped to low but variable counts in blood and to below detection limits in the spleens across the time points. Reductions in counts for antimicrobial combination groups for both blood and spleen were 2 to 3 orders of magnitude lower than those for the two control groups. By 14 days, lung spore counts had dropped below the threshold of recurrent infection (<105 CFU/g tissue) in all treatment groups (16). Table 2 shows the bacterial burden remaining in the lungs and spleens from the animals that had survived to day 28 postchallenge. There were no remaining viable bacteria in spleens, and the levels in lungs were low and similar between the groups. Importantly, there was no emergence of resistance to any of the individual antimicrobial agents.

FIG 2.

Tissue bacterial loads. Control and ciprofloxacin-alone treated animals survived only to 60 and 96 h, respectively, for tissue evaluations. Spleen counts were below the level of detection for most treatments beyond 60 h. Limits of detection for individual animals were 5 CFU/ml for blood samples (A), 10 CFU/g for spleen tissue (B), and 5 CFU/g for lung tissue (C). Each point is an average from an n of 3.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial loads at 28 days

| Treatment (n)a | Bacteria (CFU/g tissue [mean ± SD]) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Spleen | Lung | |

| SWI (1) | 0 | 467 |

| Cip (3) | 0 | 325 ± 100 |

| Mer-Lin (3) | 0 | 568 ± 182 |

| Mer-Cli (3) | 0 | 365 ± 43 |

| Mer-Rif (3) | 0 | 638 ± 29 |

| Mer-Dox (3) | 0 | 965 ± 5 |

| Pen-Lin (3) | 0 | 666 ± 266 |

| Pen-Dox (3) | 0 | 380 ± 192 |

| Rif-Lin (3) | 0 | 830 ± 55 |

| Cli-Rif (3) | 0 | 562 ± 152 |

SWI, sterile water for injection; Cip, ciprofloxacin; Mer, meropenem; Lin, linezolid; Cli, clindamycin; Rif, rifampin; Dox, doxycycline; Pen, penicillin G.

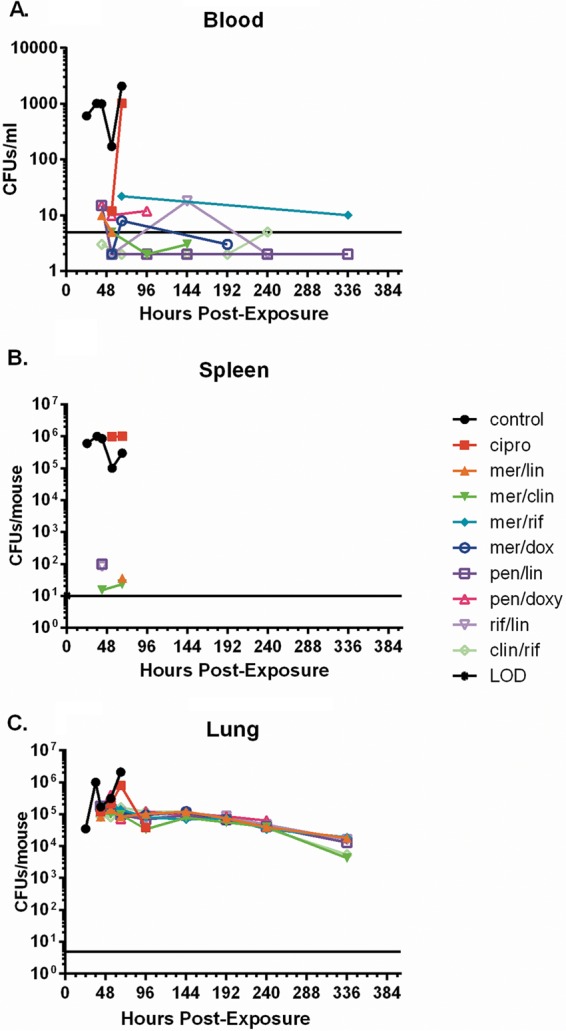

The mean lethal factor (LF) levels measured from plasma samples from 3 mice per time point during the course of treatment are shown in Fig. 3. In some cases, one or more values of the three mice per time point were below the limit of detection (LOD). These values were included in the mean at one-half the detection limit, 0.0025 ng/ml for LF, according to Hornung et al. (21). Lines at 5 ng/ml were included as reference points between the four graphs. Both the SWI and ciprofloxacin groups exceeded the 5 ng/ml threshold at many of the time points. In the 2-PS-inhibitor combination groups without a β-lactam to cover the fluoroquinolone resistance, LF levels briefly exceeded 5 ng/ml. The means for both meropenem and penicillin β-lactams groups with protein synthesis inhibitors never exceeded 5 ng/ml. Combinations with linezolid had the greatest inhibitory effect on mean LF levels, which had multiple points below the LOD by 54 to 60 h (18 to 24 h after the first treatment). By 66 h to 72 h postchallenge, LF began to fall below or near the LOD for all the other combination groups, while remaining elevated in the two control groups.

FIG 3.

Lethal factor levels during ciprofloxacin treatment with and without β-lactam and/or protein synthesis (PS) inhibitors for ciprofloxacin-resistant Bacillus anthracis. Means and standard deviations (error bars) are from lethal factor levels measured in plasma from three mice per time point per group. (A) SWI and ciprofloxacin (cipro) only controls. (B) Ciprofloxacin (cip) and meropenem (mer) with PS inhibitors linezolid (lin), clindamycin (cli), rifampin (rif), or doxycycline (dox). (C) Ciprofloxacin and penicillin (pen) with linezolid or doxycycline. (D) Ciprofloxacin and rifampin with linezolid or clindamycin. Individual mouse samples below the limit of detection (LOD) of 0.005 ng/ml (dashed lines) were given a value of one-half the LOD (0.0025 ng/ml), per Hornung et al. (21), for inclusion and appropriate weighting of the means.

DISCUSSION

Several important observations emerged from these studies. First and most importantly, multiantibiotic therapy successfully treated disease caused by a fluoroquinolone-resistant B. anthracis. Second, a β-lactam clearly provides significant added benefit against fluoroquinolone resistance; amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or penicillin VK may be acceptable oral substitutes but were not tested here. Third, the data suggest that a protein synthesis inhibitor should be considered for one of the components of combination therapy. These therapies should inhibit the synthesis of anthrax toxin components (22), thereby potentially reducing the pathology due to the anthrax toxin effects. While not directly tested here, these therapies may also inhibit the expression of the B. anthracis β-lactamase enzymes, thereby improving the efficacy of β-lactam antibiotics. A final fortuitous but important observation was obtained from the bacterial challenge dose range attained in this study. While not statistically significant, there was a small observable shift in the survival between the no-treatment control and the ciprofloxacin-alone treatment groups, presumably due to the lower challenge exposures. As a range of exposures would be expected in any outbreak or intentional release event, this observation suggests that postexposure therapy with a combination of fluoroquinolones might extend the treatment window for the individuals in a population with lower exposures, at least until the antibiotic susceptibility profile is known.

This study supports the current CDC recommendation for antimicrobial combinations for the treatment of inhalation of wild-type or modified ciprofloxacin-resistant B. anthracis strains (1). While it is important to note that these studies were performed using a “single-antibiotic-”resistant strain, the data from this study also can be applied to subsequent nonhuman primate (NHP) efficacy and PK studies to evaluate the antimicrobial agent combinations determined most effective. These data could provide further support to CDC recommendations and applications for Emergency Use Authorization for the treatment of drug-resistant anthrax infections. Combinations found effective in the NHP studies would likely be strongly considered in specific guidelines for an event involving MDR anthrax in which the first-line agents are assumed to be ineffective. Antimicrobial agents in those combinations would be identified for priority acquisition to the SNS.

Conclusions.

This is the first study to characterize the efficacy of antimicrobial combinations against a first-line anthrax antimicrobial using a ciprofloxacin-resistant strain of B. anthracis in vivo. It revealed alternative antimicrobials and antimicrobial combinations for further study that could be considered for inclusion in empirical treatment regimens for use against potential fluoroquinolone-resistant strains during an anthrax emergency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biosafety.

The University of Florida biosafety level 3 (BSL3) facility is registered by both the APHIS and the CDC. Exhaust air is HEPA filtered prior to discharge to the building exhaust system. Personnel must change into scrubs prior to entering containment and must shower prior to exiting. All personnel wear personal protective equipment, including respiratory protection, full body Tyvek suits, double gloves, and disposable booties, at all times. All work with agents in the suite is performed in either class II or class III biological safety cabinets. All waste generated in the BSL3 is autoclaved in dedicated pass-through autoclaves for removal.

Strain and characterization.

Strain BACr4-2 is a ciprofloxacin-resistant (Cipr) derivative of the B. anthracis Ames strain that was originally isolated from a failed ciprofloxacin dose range/fractionation treatment arm in an Ames mouse challenge study. The strain was characterized for antibiotic susceptibility as previously described (17, 23, 24) and evaluated for an increase in active efflux (14). Virulence was assessed in the mouse aerosol system using LD50 and the mean time to death (MTD) (15) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The strain also underwent sequencing of the QRDR regions of both the gyrase and topoisomerase IV genes by PCR (15) to identify the specific fluoroquinolone resistance mutation(s).

Preparation of the B. anthracis challenge strain for aerosolization.

Spores were prepared according to the method of Leighton and Doi (25). Spores for aerosol challenge were maintained in sterile water and diluted to the nebulizer-challenge concentration of approximately 1 × 1010 CFU/ml.

Animal study protocol.

Female BALB/c mice 6 to 8 weeks old from Charles River, NCI colony, Frederick, MD, were used in these experiments. Animals were acclimated for 1 week prior to the aerosol challenge. Research was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adhered to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (26). The facility where this research was conducted is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. The study had IACUC approval at both the CDC and the University of Florida (UF). Additionally approvals from the Institutional Biosafety Committee (UF) and the Institutional Biosecurity Board (CDC) were also obtained.

Aerosol infection.

The target exposure was 50 LD50s by whole body exposure (LD50 = 2 × 104 CFU/whole body). The aerosol was generated using a three-jet Collison nebulizer (27). All aerosol procedures were controlled and monitored using an automated bioaerosol exposure system operating with a whole-body rodent exposure chamber (28). Integrated air samples were obtained from the chamber during each exposure using an all-glass impinger. To verify final bacterial concentrations and exposure doses, colonies were enumerated after serial dilution and plating on sheep blood agar plates (SBA). These plates were incubated at 35°C overnight and colonies were enumerated. The inhaled dose (CFU/mouse) of B. anthracis was estimated using the mouse respiratory rate derived from Guyton's formula (29).

Challenge and combination treatment protocol.

Ten experimental groups of 46 animals were aerosol challenged with spores prepared from BACr4-2 in a total of 9 aerosol runs. Fifty mice were exposed in runs 1 to 8 and 60 mice in run 9 for a total of 460. Five mice from runs 1 to 8 and six from run 9 were distributed to each treatment group (46 mice). This exposure sequence equalized all experimental groups. Simultaneous exposure of all animals was not possible because of the capacity and variance of the aerosol system. The study control and experimental arms are detailed in Table 3. Survival cohorts of 10 mice from each experimental group were followed for the evaluation of efficacy. Antimicrobial treatment strategies (detailed below) initiated at 36 h postchallenge were administered every 6 or 12 h (q6h or q12h, respectively) for 14 days. Mortality was assessed and recorded every 6 h during antimicrobial agent administration and at least twice daily thereafter out to 28 days after challenge.

TABLE 3.

Control and combination antimicrobial groupsa

| Treatment group | Drug | Dosage (mg/kg body weight) |

|---|---|---|

| SWI control (no treatment control) | Vehicle (SWI) | q12h |

| Ciprofloxacin control | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| 1 | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| Meropenem | 100, q6h | |

| Linezolid | 50, q12h | |

| 2 | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| Meropenem | 100, q6h | |

| Clindamycin | 50, q6h | |

| 3 | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| Meropenem | 100, q6h | |

| Rifampin | 50, q6h | |

| 4 | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| Meropenem | 100, q6h | |

| Doxycycline | 40, q12h | |

| 5 | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| Penicillin G | 100, q6h | |

| Linezolid | 50, q12h | |

| 6 | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| Penicillin G | 100, q6h | |

| Doxycycline | 40, q12h | |

| 7 | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| Rifampin | 50, q6h | |

| Linezolid | 50, q12h | |

| 8 | Ciprofloxacin | 30, q12h |

| Clindamycin | 50, q6h | |

| Rifampin | 50, q6h |

Intraperitoneal administration of the antibiotics in mice commenced at 36 h for 14 days at the indicated dosages.

Antimicrobial lots and doses.

All antimicrobial agents were pharmaceutical grade with the exception of ciprofloxacin (lot P500044; Sigma-Aldrich) and rifampin (lots L0114 and G0815; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used, as there was a nation-wide shortage of pharmaceutical-grade versions of these two agents. Lots for the pharmaceutical-grade antimicrobial agents were as follows: doxycycline, lot 6109961 (Fresenius Kabi); meropenem, lot 608F001 (Hospira); linezolid, lot 6300814 (Teva); clindamycin, lot 36-251-EV (Hospira); and penicillin G, lot P5636 (WG Critical Care). All were formulated to dose concentrations with SWI, which also served as the control, as follows: ciprofloxacin, 30 mg/kg of body weight q12h; doxycycline, 40 mg/kg q12h; clindamycin, 50 mg/kg q6h; linezolid, 50 mg/kg q12h; meropenem, 100 mg/kg q6h; penicillin G, 100 mg/kg q6h; and rifampin, 50 mg/kg q6h.

Bacterial load in blood, lung, and spleen.

Of the remaining 36 animals in each experimental group, three per group were serially euthanized at 24 and 36 h (control group) and at 42, 48, 54, 60, 66, and 72 h and at 4, 6, 8, 10, and 14 days. Animals were bled via cheek bleeds into heparinized blood collection tubes. Euthanasia was performed using CO2 and the lungs and spleens were removed. Tissues were weighed and homogenized in 1 ml sterile water. One hundred microliters of whole blood and tissue homogenates were serially diluted and plated on SBA and tryptic soy agar containing 3× MIC of individual antibiotics specific for the antibiotic combinations in each treatment group. After overnight incubation at 35°C, the total bacterial burden and the presence of less-susceptible isolates were determined and quantitated. Limits of detection (LOD) were 5 CFU/ml for blood samples, 5 CFU/g for lungs, and 10 CFU/g for spleens.

Anthrax lethal factor testing.

The remaining blood was centrifuged to collect plasma, which was filtered, tested for sterility, and then shipped to the CDC for analysis of lethal factor (LF) by mass spectrometry (MS) at the Division of Laboratory Sciences, Clinical Chemistry Branch. A detailed analysis of LF by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) MS was described previously (30, 31). LF is a zinc endoproteinase that cleaves and inactivates proteins involved in immune signaling (32). The sensitivity of the MS method is derived from the detection of LF cleavage activity rather than the detection of LF itself. LF cleavage of its target peptide is very specific, and cleaved products accumulate over time. These amplified LF cleavage products are detected and quantified by MS. Briefly, LF analysis included 3 steps: (i) LF from plasma was purified by anti-LF monoclonal antibodies on magnetic beads, (ii) the concentrated LF on the beads was reacted with and hydrolyzed a peptide substrate designed to mimic its natural target, and (iii) the cleaved peptide products were detected and quantified by isotope-dilution MALDI-TOF MS (30). The limit of detection (LOD) for LF for this assay was 0.005 ng/ml.

Data reporting and statistical analyses.

All analyses were performed employing a stratified Kaplan-Meyer analysis with a log-rank test as implemented on Prism version 5.03 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The sample size was based on the minimum sample size required for statistical significance for comparing each experimental arm with controls using a log-rank analysis of survival and a paired analysis of variance (ANOVA) (with Bonferroni's adjustment). The study sample size was validated in a previous report using the murine experimental model for in vivo analysis of the efficacy of antimicrobial agents for inhalation anthrax (16). LF levels are reported in ng/ml. Means and standard deviations from LF results for each group and time point were determined with available formulas in Microsoft Excel.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by CDC contract no. 200-2011041350.

The opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the CDC or the University of Florida.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00788-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hendricks KA, Wright ME, Shadomy SV, Bradley JS, Morrow MG, Pavia AT, Rubinstein E, Holty JE, Messonnier NE, Smith TL, Pesik N, Treadwell TA, Bower WA. 2014. Workgroup on Anthrax Clinical Guidelines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert panel meetings on prevention and treatment of anthrax in adults. Emerg Infect Dis 202. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.130687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inglesby TV, O'Toole T, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Friedlander AM, Gerberding J, Hauer J, Hughes J, McDade J, Osterholm MT, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Tonat K. 2002. Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002: updated recommendations for management. JAMA 287:2236–2252. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern EJ, Uhde KB, Shadomy SV, Messonnier N. 2008. Conference report on public health and clinical guidelines for anthrax. Emerg Infect Dis 14. doi: 10.3201/eid1404.070969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalns J, Morris J, Eggers J, Kiel J. 2002. Delayed treatment with doxycycline has limited effect on anthrax infection in BLK57/B6 mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 297:506–509. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02226-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heine HS, Purcell BK, Bassett J, Miller L, Goldstein BP. 2010. Activity of dalbavancin against Bacillus anthracis in vitro and in a mouse inhalation anthrax model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:991–996. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00820-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson JW, Moen ST, Healy D, Pawlik JE, Taormina J, Hardcastle J, Thomas JM, Lawrence WS, Ponce C, Chatuev BM, Gnade BT, Foltz SM, Agar SL, Sha J, Klimpel GR, Kirtley ML, Eaves-Pyles T, Chopra AK. 2010. Protection afforded by fluoroquinolones in animal models of respiratory infections with Bacillus anthracis, Yersinia pestis, and Francisella tularensis. Open Microbiol J 3(4):34–46. doi: 10.2174/1874285801004010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holty JE, Kim RY, Bravata DM. 2006. Anthrax: a systematic review of atypical presentations. Ann Emerg Med 48:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jernigan JA, Stephens DS, Ashford DA, Omenaca C, Topiel MS, Galbraith M, Tapper M, Fisk TL, Zaki S, Popovic T, Meyer RF, Quinn CP, Harper SA, Fridkin SK, Sejvar JJ, Shepard CW, McConnell M, Guarner J, Shieh WJ, Malecki JM, Gerberding JL, Hughes JM, Perkins BA, Anthrax bioterrorism Investigation Team. 2001. Bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax: the first 10 cases reported in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 7:933–944. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pillai SK, Huang E, Guarnizo JT, Hoyle JD, Katharios-Lanwermeyer S, Turski TK, Bower WA, Hendricks KA, Meaney-Delman D. 2015. Antimicrobial treatment for systemic anthrax: analysis of cases from 1945 to 2014 identified through a systematic literature review. Health Secur 13:355–364. doi: 10.1089/hs.2015.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katharios-Lanwermeyer S, Holty JE, Person M, Sejvar J, Haberling D, Tubbs H, Meaney-Delman D, Pillair SK, Hupert N, Bower WA, Hendricks K. 2016. Identifying meningitis during an anthrax mass casualty incident: systematic review of systemic anthrax since 1880. Clin Infect Dis 62:1537–1545. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Louie A, Heine HS, Kim K, Brown DL, VanScoy B, Liu W, Kinzig-Schippers M, Sörgel F, Drusano GL. 2008. Use of an in vitro model of Bacillus anthracis infection to derive a linezolid regimen that optimizes bacterial kill and prevents emergence of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2486–2496. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01439-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louie A, Vanscoy BD, Heine HS, Liu W, Abshire T, Holman K, Kulawy R, Brown DL, Drusano GL. 2012. Differential effect of linezolid and ciprofloxacin on toxin production by Bacillus anthracis in an in vitro pharmacodynamic system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:513–517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05724-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell DM, Korzarsky PE, Stephens DS. 2002. Conference summary: clinical issues in the prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment of anthrax. Emerg Infec Dis J. 8:222–225. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.01-0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bast DJ, Athamna A, Duncan CL, de Azavedo JCS, Low DE, Rahav G, Farrell D, Rubinstein E. 2004. Type II topoisomerase mutations in Bacillus anthracis associated with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 54:90–94. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price LB, Vogler A, Pearson T, Busch JD, Schupp JM, Keim P. 2003. In vitro selection and characterization of Bacillus anthracis mutants with high-level resistance to ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2362–2365. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2362-2365.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heine HS, Bassett J, Miller L, Hartings JM, Ivins BE, Pitt ML, Fritz D, Norris SL, Byrne WR. 2007. Determination of antibiotic efficacy against Bacillus anthracis in a mouse aerosol challenge model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:1373–1379. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01050-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heine HS, Bassett J, Miller L, Bassett A, Ivins BE, Lehoux D, Arhin FF, Parr TR, Moeck G. 2008. Efficacy of oritavancin in a murine model of Bacillus anthracis spore inhalation anthrax. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:3350–3357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00360-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Tenover FC, Koehler TM. 2004. β-Lactamase gene expression in a penicillin-resistant Bacillus anthracis strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:4873–4877. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4873-4877.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Materon IC, Queenan AM, Koehler TM, Bush K, Palzkill T. 2003. Biochemical characterization of β-lactamases Bla1 and Bla2 from Bacillus anthracis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2040–2042. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.6.2040-2042.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2010. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria, 2nd ed, vol 30, no. 18 Approved guideline M45-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hornung RW, Reed LD. 1990. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of nondetectable values. Appl Occup Environ Hug. 5:46–51. doi: 10.1080/1047322X.1990.10389587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shadomy SV, Heine HS, Boyer AE, Barr JR, Pesik NT, Smith TL. 2011. Efficacy of five FDA-licensed antimicrobial agents for post-exposure prophylaxis following Bacillus anthracis inhalation exposure in a murine model. 5th PHEMCE Stakeholders Workshop, Washington, DC, 10 to 12 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill SC, Rubino CM, Bassett J, Miller L, Ambrose PG, Bhavani SM, Beaudry A, Li J, Stone KC, Critchley I, Janjic N, Heine HS. 2010. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic assessment of faropenem in a lethal murine Bacillus anthracis inhalation postexposure prophylaxis model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1678–1683. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00737-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maples KR, Wheeler C, Ip E, Plattner JJ, Chu D, Zhang YK, Preobrazhenskaya MN, Printsevskaya SS, Solovieva SE, Olsufyeva EN, Heine H, Lovchik J, Lyons CR. 2007. Novel semisynthetic derivative of antibiotic Eremomycin active against drug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens, including Bacillus anthracis. J Med Chem 50:3681–3685. doi: 10.1021/jm0700058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leighton TJ, Doi RH. 1971. The stability of messenger ribonucleic acid during sporulation in Bacillus anthracis. J Biol Chem 246:3189–3195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Research Council. 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academy Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 27.May KR. 1973. The Collison nebulizer: description, performance and applications. J Aerosol Sci 4:235–243. doi: 10.1016/0021-8502(73)90006-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartings JM, Roy CJ. 2004. The automated bioaerosol exposure system: preclinical platform development and a respiratory dosimetry application with nonhuman primates. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 49:39–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guyton AC. 1947. Measurement of the respiratory volumes of laboratory animals. Am J Physiol 150:70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyer AE, Quinn CP, Woolfitt AR, Pirkle JL, McWilliams LG, Stamey KL, Bagarozzi DA, Hart JC Jr, Barr JR. 2007. Detection and quantification of anthrax lethal factor in serum by mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 79:8463–8470. doi: 10.1021/ac701741s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyer AE, Gallegos-Candela M, Lins RC, Kuklenyik Z, Woolfitt A, Moura H, Kalb S, Quinn CP, Barr JR. 2011. Quantitative mass spectrometry for bacterial protein toxins–a sensitive, specific, high-throughput tool for detection and diagnosis. Molecules 16:2391–2413. doi: 10.3390/molecules16032391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bromberg-White J, Lee CS, Duesbery N. 2010. Consequences and utility of the zinc-dependent metalloprotease activity of anthrax lethal toxin. Toxins (Basel) 2:1038–1053. doi: 10.3390/toxins2051038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.