ABSTRACT

The nafithromycin concentrations in the plasma, epithelial lining fluid (ELF), and alveolar macrophages (AM) of 37 healthy adult subjects were measured following repeated dosing of oral nafithromycin at 800 mg once daily for 3 days. The values of noncompartmental pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters were determined from serial plasma samples collected over a 24-h interval following the first and third oral doses. Each subject underwent one standardized bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) at 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, or 48 h after the third dose of nafithromycin. The mean ± standard deviation values of the plasma PK parameters after the first and third doses included maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) of 1.02 ± 0.31 μg/ml and 1.39 ± 0.36 μg/ml, respectively; times to Cmax of 3.97 ± 1.30 h and 3.69 ± 1.28 h, respectively; clearances of 67.3 ± 21.3 liters/h and 52.4 ± 18.5 liters/h, respectively, and elimination half-lives of 7.7 ± 1.1 h and 9.1 ± 1.7 h, respectively. The values of the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) from time zero to 24 h postdosing (AUC0–24) for nafithromycin based on the mean or median total plasma concentrations at BAL fluid sampling times were 16.2 μg · h/ml. For ELF, the respective AUC0–24 values based on the mean and median concentrations were 224.1 and 176.3 μg · h/ml, whereas for AM, the respective AUC0–24 values were 8,538 and 5,894 μg · h/ml. Penetration ratios based on ELF and total plasma AUC0–24 values based on the mean and median concentrations were 13.8 and 10.9, respectively, whereas the ratios of the AM to total plasma concentrations based on the mean and median concentrations were 527 and 364, respectively. The sustained ELF and AM concentrations for 48 h after the third dose suggest that nafithromycin has the potential to be a useful agent for the treatment of lower respiratory tract infections. (This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under registration no. NCT02453529.)

KEYWORDS: alveolar macrophages, epithelial lining fluid, nafithromycin, pharmacokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Nafithromycin (WCK 4873) is a novel lactone ketolide with potent in vitro antimicrobial activity against both typical and atypical pathogens commonly associated with community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections (1–7). Nafithromycin has demonstrated potent in vitro activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae (MIC90 = 0.06 mg/liter; 100% of 1,911 isolates had MIC values of ≤0.25 mg/liter), including macrolide-resistant and telithromycin-nonsusceptible strains (1–3). It has also been demonstrated to have potent in vitro activity against a wide range of other bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis) (2, 3). It has also been confirmed to have in vitro activity against atypical pathogens, such as Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydophila pneumoniae (4–7). An ongoing phase 2, randomized, double-blind, comparative study is evaluating oral nafithromycin for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia in adults (ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT02903836).

Epithelial lining fluid (ELF) and alveolar macrophages (AM) are considered important sites for lower respiratory tract infections caused by extracellular and intracellular pathogens, respectively (8, 9). Antimicrobial agents, such as macrolides (e.g., clarithromycin, azithromycin) and ketolides (e.g., telithromycin, cethromycin, solithromycin), have been shown to have markedly higher drug concentrations in ELF and AM than plasma (9–16). The objectives of this study were to compare the plasma, ELF, and AM concentrations of nafithromycin and determine the safety and tolerability of multiple oral doses (800 mg once daily for three consecutive days) of nafithromycin in healthy adult subjects (ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT02453529).

(This work was presented in part at ASM Microbe 2016, Boston, MA, June 2016.)

RESULTS

Subjects.

A total of 38 subjects were enrolled in this study. The data for one subject who completed all phases of the study were not included in the pharmacokinetic analysis since the study entry inclusion and exclusion criteria were not met. The characteristics of the 37 study subjects who met the study entry criteria and completed at least one phase of the pharmacokinetic data collection are reported in Table 1. The only notable differences across sampling times for demographic characteristics were gender and total cell count in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (the mean value for the 48-h sampling time was higher than that for the other sampling times).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study subjects receiving oral nafithromycin at 800 mg once daily for 3 daysa

| Sampling time (h) | Sex (no. of subjects) | Age (yr) | Ht (cm) | Wt (kg) | Total cell count in BAL fluid (mm3) | % of macrophages in BAL fluid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | M (6) | 41 ± 12 | 176 ± 6 | 76.7 ± 5.9 | 70 ± 26 | 77 ± 15 |

| 6 | M (4), F (2) | 37 ± 8 | 170 ± 11 | 78.4 ± 9.6 | 103 ± 37 | 83 ± 7 |

| 9 | M (5), F (1) | 37 ± 9 | 174 ± 14 | 76.4 ± 11.5 | 68 ± 23 | 81 ± 8 |

| 12 | M (2), F (4) | 38 ± 8 | 165 ± 4 | 69.5 ± 9.2 | 86 ± 87b | 67 ± 19b |

| 24 | M (7) | 39 ± 10 | 176 ± 4 | 78.2 ± 12.4 | 99 ± 56c | 73 ± 17c |

| 48 | M (5), F (1) | 42 ± 5 | 173 ± 10 | 72.9 ± 10.3 | 150 ± 88 | 86 ± 8 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± 1 SD for all characteristics except sex. Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; BMI, body mass index.

Data are for 5 of 6 subjects at this sampling time.

Data are for 6 of 7 subjects at this sampling time.

Twenty-five of 38 subjects (65.8%) experienced a total of 37 adverse events over the course of the study. One serious adverse event (paranoia) occurred after discharge of the subject from the study site and was considered unlikely to be related to nafithromycin. All other adverse events were mild (n = 34) to moderate (n = 2) in severity. The most frequently reported adverse events (≥10% of subjects) included dysgeusia (i.e., bad taste) in 18 subjects and headache in 4 subjects. Twenty-five adverse events were considered to be certainly related (n = 20), possibly related (n = 4), or probably or likely related (n = 1) to nafithromycin administration. The remaining 12 adverse events were considered unlikely to be related or unrelated to nafithromycin. No clinically significant laboratory, vital sign, electrocardiogram (ECG), or physical examination findings were observed in this study.

Pharmacokinetics.

Thirty-seven study subjects completed at least one phase of the pharmacokinetic data collection. One subject (in the group sampled at 24 h) had only plasma concentration-time data (for both the first and the third doses) and was included for the plasma pharmacokinetic parameter analysis only since a bronchoscopy was not completed. An additional subject was enrolled to undergo a bronchoscopy at this sampling time in order to obtain a complete plasma and intrapulmonary concentration-time profile. A second subject (in the group sampled at 48 h) completed all phases of the pharmacokinetic study; however, the clinical laboratory was unable to measure an accurate differential of cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Only the plasma and ELF concentration-time data for this subject were used in the pharmacokinetic analysis. A third subject (in the group sampled at 12 h) had significantly lower plasma, ELF, and AM concentrations after the third dose than after the first dose and than in the plasma, ELF, and AM of all other subjects. Only the plasma concentration-time data for the first dose for this subject were included in the pharmacokinetic analysis.

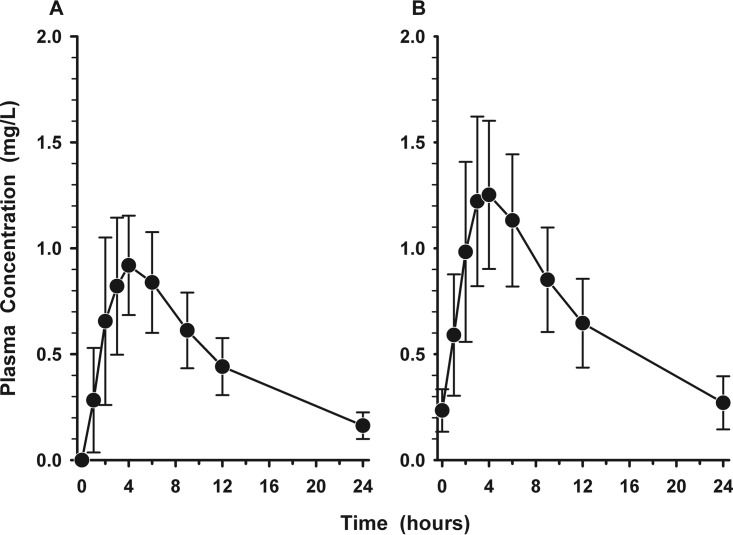

Figures 1A and B display the mean ± standard deviation (SD) plasma concentration-versus-time profiles for nafithromycin following the first and third doses, respectively. The mean ± SD values of the pharmacokinetic parameters for nafithromycin in plasma after the first and third doses are listed in Table 2. On average, the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) increased by 37% (from 1.015 mg/liter on day 1 to 1.387 mg/liter on day 3) and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) increased by 29% (from 12.89 mg · h/liter on day 1 to 16.64 mg · h/liter on day 3). The mean ± SD plasma concentrations of nafithromycin at 24 h after the first (24 h), second (48 h), and third (72 h) doses were 0.162 ± 0.063 mg/liter, 0.234 ± 0.100 mg/liter, and 0.270 ± 0.125 mg/liter, respectively. Trough concentrations progressively increased and approached steady state by the third dose of oral administration of nafithromycin.

FIG 1.

Mean ± SD plasma concentration-versus-time profile of nafithromycin before and in the 24-h interval following the first (A) and third (B) oral doses of 800 mg once daily.

TABLE 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for nafithromycin at 800 mg in plasmaa

| Dose | Cmax (mg/liter) | Tmax (h) | AUCb (mg · h/liter) | t1/2 (h) | V/F (liters) | CL/F (liters/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1.015 ± 0.314 | 3.97 ± 1.30 | 12.89 ± 3.77 | 7.69 ± 1.14 | 731 ± 190 | 67.3 ± 21.3 |

| Third | 1.387 ± 0.361 | 3.69 ± 1.28 | 16.64 ± 4.58 | 9.05 ± 1.72 | 666 ± 201 | 52.4 ± 18.5 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

AUC for the first dose was AUC0–∞, and AUC for the third dose was AUC0–24.

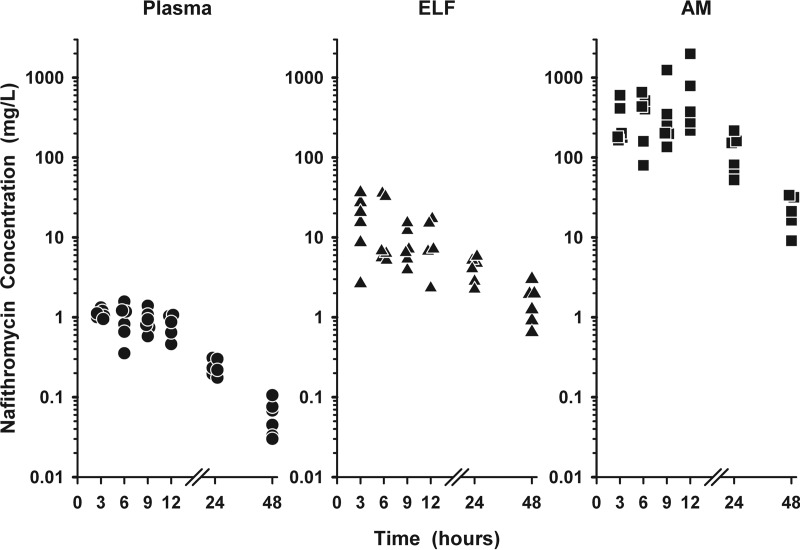

The individual plasma (total), ELF, and AM concentrations of nafithromycin following the third dose are shown in Fig. 2. Once-daily dosing of nafithromycin at 800 mg produced steady-state concentrations in ELF (2.5 to 36.3 times) and AM (134 to 1,862 times) higher than the simultaneous concentrations in plasma (total) throughout the 24-h dosing interval. The concentrations of nafithromycin in ELF (20.2 to 37.8 times) and AM (202 to 707 times) also remained higher than the concentrations in plasma (total) in the six subjects having a sampling time of 48 h after the third dose.

FIG 2.

Individual concentrations of nafithromycin in plasma (circles), epithelial lining fluid (ELF; triangles), and alveolar macrophages (AM; squares) at 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 48 h after the third oral dose of 800 mg once daily. The data on the y axis are on the log scale.

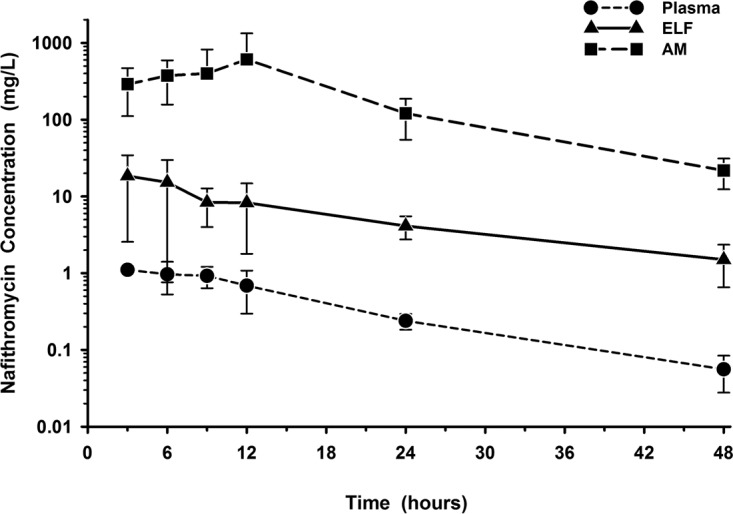

The mean ± SD concentrations of nafithromycin in plasma (total), ELF, and AM after three oral doses are reported in Table 3. The highest mean ELF concentrations of nafithromycin occurred at the 3-h sampling time, whereas the highest mean AM concentrations occurred at the 12-h sampling time. The mean ± SD concentrations of nafithromycin in plasma (total), ELF, and AM at the bronchopulmonary sampling times are illustrated in Fig. 3. It is noteworthy that the ELF and AM concentrations remained measurable at 48 h after the third dose, with the mean ± SD values being 1.62 ± 0.86 and 22.4 ± 10.4 μg/ml, respectively. The values of AUC from time zero to 24 h postdosing (AUC0–24) based on the mean and median ELF concentrations were 224.1 and 176.3 mg · h/liter, respectively. The ratio of the ELF to total plasma nafithromycin concentrations based on the mean and median AUC0–24 values were 13.8 and 10.9, respectively. The AUC0–24 values based on the mean and median concentrations in AM were 8,538 and 5,894 mg · h/liter, respectively. The ratio of the AM to the total plasma nafithromycin concentrations based on the mean and median AUC0–24 values were 527 and 364, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Nafithromycin concentrations in plasma, ELF, and AM at time of bronchoscopy and BALa

| Sampling time (h) | Nafithromycin concn (mg/liter) in: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ELF | AM | |

| 3b | 1.105 ± 0.140 | 18.48 ± 12.31 | 290.2 ± 179.0 |

| 6b | 0.966 ± 0.439 | 15.29 ± 14.53 | 375.4 ± 218.2 |

| 9b | 0.922 ± 0.286 | 8.37 ± 4.38 | 401.1 ± 420.3 |

| 12c | 0.817 ± 0.261 | 9.67 ± 6.20 | 729.4 ± 739.0 |

| 24d | 0.239 ± 0.055 | 4.13 ± 1.38 | 120.9 ± 66.2 |

| 48b | 0.060 ± 0.029 | 1.62 ± 0.86 | 22.4 ± 10.4 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± 1 SD.

Data are for six concentrations per matrix at this sampling time.

Data are for five concentrations per matrix at this sampling time.

Data are for six plasma and ELF concentrations and five AM concentrations at this sampling time.

FIG 3.

Mean ± SD concentration-versus-time profiles of nafithromycin in plasma, epithelial lining fluid (ELF), and alveolar macrophages (AM) at 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 48 h after the third oral dose of 800 mg once daily. The data on the y axis are on the log scale.

DISCUSSION

The plasma concentration-time data observed in our study are similar to those observed in two preliminary reports describing the pharmacokinetics of orally administered nafithromycin in healthy subjects (17, 18). The mean ± SD Cmax of nafithromycin after the first dose of 800 mg in our study was 1.015 ± 0.314 mg/liter (at a mean time to Cmax [Tmax] of 3.97 h), whereas the reported range of mean Cmax values after a single dose was 0.932 to 1.207 mg/liter (at mean Tmax ranging from 3.88 to 4.0 h). Our observed value for the AUC from time zero extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞) after the first dose (12.89 ± 3.77 mg · h/liter) was consistent with the values observed in subjects who received a single 800-mg dose in the fasted (12.49 mg · h/liter) or fed (14.85 mg · h/liter) state or on the first day (AUC0–24, 11.99 mg · h/liter) of a multiple-dose study. Previously reported data provided evidence that the plasma exposure of nafithromycin was only mildly increased by food (AUC and Cmax were approximately 1.2 to 1.3 times higher than those in the fasted state), and measurements of plasma exposure were increased in a greater than dose-proportional manner over the 100-mg to 1,200-mg single-dose range (17, 18). These reported differences in the AUC and Cmax values between the three studies are small and most likely explained because of differences in the study design, subject enrollment, and pharmacokinetic data analysis.

The intrapulmonary concentrations of nafithromycin were significantly higher than the simultaneous total plasma concentrations throughout the 24-h dosing interval on day 3 and up to 48 h after the third dose (Fig. 3). Similar to other ketolide, azalide, and macrolide agents, the levels of ELF and AM exposure (measured by AUC) for nafithromycin were over 10-fold and 100-fold higher, respectively, than the total plasma concentrations (9–16). Because the pattern and time course of ELF and AM concentrations are mutual among these agents, the major difference between agents is the absolute magnitude of exposure in each matrix. In general, agents with higher total plasma exposure usually have higher ELF and AM exposures. For example, solithromycin, a fluoroketolide, had an AUC0–24 (based on the median concentrations at BAL fluid sampling times) of 7.8, 80.3, and 1,498 mg · h/liter in plasma, ELF, and AM, respectively (16). In comparison, nafithromycin had an AUC0–24 (based on the median concentrations at BAL fluid sampling times) of 16.2 mg · h/liter in plasma, which was approximately 2.5-fold higher than that of solithromycin. The increase in plasma exposure of nafithromycin resulted in AUC0–24 values of 176.2 mg · h/liter and 5,894 mg · h/liter in ELF and AM, respectively, which translates to values that are approximately 2.8- and 4.6-fold higher in ELF and AM, respectively, than those observed for solithromycin. This becomes even more important when considering other ketolides (e.g., telithromycin, cethromycin) and azithromycin, whose AUC0–24 values for plasma, ELF, and AM exposures were markedly lower than those of nafithromycin (9–11, 13–15). The higher plasma exposure and increased drug concentrations in the intrapulmonary compartments will likely be a significant advantage for nafithromycin over older agents.

The ratio of the AUC0–24 to the MIC (AUC0–24/MIC) has been suggested to be the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameter that best correlates with the efficacy of macrolides, azalides, and ketolides (9–16). Two preliminary studies have suggested that both ELF and unbound plasma AUC0–24/MIC ratios were the parameters predictive of the efficacy of nafithromycin (19, 20). Bader and colleagues described a population pharmacokinetic model (based on three phase 1 pharmacokinetic studies, including data from this report) and used the median ELF AUC/MIC ratio target of 833, associated with a reduction of 1 log10 in the number of CFU of isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae, including telithromycin-nonsusceptible strains, from the baseline (19). The percent probabilities of target attainment were ≥99.6% at the MIC90 value of 0.06 mg/liter and ≥94.0% for four ELF and plasma AUC/MIC ratios against a worldwide collection of 1,911 strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae for an 800-mg once-daily dosing regimen of 3 days' duration. Satav and colleagues have recently demonstrated that for Haemophilus influenzae the ELF AUC0–24/MIC ratio associated with a 1 log10 reduction in the number of CFU from the baseline was 16.19 in a neutropenic mouse model of lung infection (20). The in vitro activity of nafithromycin against Haemophilus influenzae in this study included strains with MIC values of 4 and 8 mg/liter. Combining these pharmacodynamic concepts and MIC values with our observed median ELF AUC0–24 value (176.3 mg · h/liter), the estimated AUC0–24/MIC90 ratios in ELF would be 2,938 for a Streptococcus pneumoniae strain with an MIC of 0.06 mg/liter and 44 and 27 for Haemophilus influenzae strains with MICs of 4 and 8 mg/liter, respectively. These preliminary reports of findings from pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic studies have provided support for selection of the dosage to be used against extracellular pathogens in the ongoing phase 2 comparative study evaluating oral nafithromycin at 800 mg once daily for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia in adults (ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT02903836).

Nafithromycin has potent in vitro activity against intracellular respiratory pathogens, including Legionella pneumophila (MIC90, 0.03 mg/liter), Chlamydophila pneumoniae (MIC90, 0.25 mg/liter), and the atypical pathogen Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MIC90, 0.000125 mg/liter) (4–7). Nafithromycin has also been demonstrated to have potent in vitro bactericidal activity against erythromycin-resistant strains of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 using an intracellular infection model with human monocytes (5). The concentrations of nafithromycin in AM during the 24-h dosing interval ranged from 52.5 to 1,990 mg/liter, with 86% of these AM concentrations being greater than 100 mg/liter (Fig. 2). The individual AM concentrations at the 48-h sampling time ranged from 9.1 to 33.8 mg/liter (mean, 22.4 mg/liter). The ratios of the AM to the simultaneous total plasma concentrations in individual subjects ranged from 134 to 1,861, with the AUC0–24 ratios based on the mean and median concentration values being 527 and 364, respectively. While no pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters predictive of activity against these atypical pathogens have been established, the potent in vitro potency and extremely high intracellular concentrations in AM would suggest that nafithromycin should have efficacy against these atypical respiratory pathogens.

The ELF and AM penetration ratios of nafithromycin reported throughout this article were based on total (bound plus unbound) plasma drug concentrations. The mean percent protein binding of nafithromycin at concentrations of 2.5 and 10 mg/liter in human serum was 62% and 72%, respectively (Wockhardt Ltd., data on file, correspondence from 14 September 2015). As has been demonstrated in this study, the ELF and AM concentrations and the ratios of the ELF and AM to total plasma concentrations represent some of the highest observed among the ketolide, azalide, and macrolide agents. If the unbound plasma concentrations were used, our penetration ratios for ELF and AM would be even greater than those that we have reported when we used total plasma concentrations. From a pharmacodynamics perspective, the preliminary studies have suggested that AUC0–24/MIC ratios based on values obtained from unbound plasma or ELF concentrations may be predictive of the efficacy of nafithromycin (19, 20).

In summary, the results of this study provide important information on the time course and magnitude of the extracellular and intracellular concentrations of nafithromycin in the lung. Oral administration of nafithromycin at 800 mg produced higher concentrations in ELF (2.5 to 37.9 times) and AM (134 to 1,861 times) than the simultaneous concentrations in plasma throughout the 48-h period after 3 days of once-daily dosing. The ratios of ELF to plasma concentrations and AM to plasma concentrations based on the median AUC0–24 values were >10 and >350, respectively. The in vitro activity of nafithromycin against common typical and atypical pathogens and the sustained concentrations of nafithromycin in ELF and AM suggest that nafithromycin has the potential to be a useful antibacterial agent for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and subjects.

This was a phase 1, multiple-dose, open-label pharmacokinetic study in healthy male and female adult subjects. The protocol was approved by the Quorum Review Institutional Review Board (Seattle, WA), and the subjects were enrolled after informed, written consent was obtained. Healthy subjects between the ages of 18 and 55 years without evidence of organ dysfunction or significant laboratory abnormalities were eligible for inclusion in the study. All subjects were required to have a baseline medical history, physical examination, laboratory evaluation, and electrocardiogram (ECG) within 28 days (at the screening visit and/or the baseline) prior to nafithromycin administration. Subjects had to have body weights between 55 and 100 kg and body mass indexes between 18.5 and 30 kg/m2; the values for both characteristics are inclusive. The estimated creatinine clearance needed to be ≥60 ml/min both at the screening visit and at baseline testing. Male subjects engaging in sexual activity and female subjects of childbearing potential were required to use two highly effective methods of birth control (as defined in the protocol) from the time of the screening visit until 30 days following the last dose of nafithromycin. Male subjects were also not allowed to donate sperm for 90 days after the last dose of nafithromycin.

Exclusion criteria included a history or presence of clinically significant medical disorders, surgeries, or concurrent infection; alcohol or drug abuse within the past 2 years; excessive intake of alcohol within the last 6 months before the screening visit; positive laboratory tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus surface antigen, or anti-hepatitis C virus antibody; hypersensitivity or idiosyncratic adverse reactions to any macrolide, azalide, or ketolide antibiotics; allergy or other serious adverse reactions to lidocaine or benzodiazepines; and any clinically significant baseline laboratory abnormalities. Subjects must not have had a history of tobacco use (defined as smoking or the use of snuff chewing tobacco and other nicotine or nicotine-containing products) during the 6 months before the screening procedures. Subjects were excluded if the QTcF interval was greater than 450 ms or they had a history of prolonged QT syndrome at the screening visit. Female subjects who were pregnant or lactating were excluded. Subjects could not have received a prescription drug (with the exception of hormonal contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy) within 14 days before the first dose of nafithromycin. Unless prior approval was granted by the investigators and the sponsor, the use of acetaminophen, multivitamins and vitamin C, and all other nonprescription medications (including health supplements and herbal remedies) was prohibited within 3, 7, and 14 days before the first dose of nafithromycin, respectively. Subjects could not have a positive alcohol breath test or urine drug screen test at the time of screening or on day 1 of baseline laboratory testing. Beverages or food containing caffeine or grapefruit could not be consumed within 48 h prior to the first dose of nafithromycin and until the time of discharge from the clinical research center. Subjects could not have donated blood or experienced significant blood loss within 60 days of the screening visit. Subjects could not have received an investigational drug or device or participated in another research study within 30 days or 5 half-lives of the investigational agent (whichever was longer) before the screening visit.

Each subject received 800 mg (2 tablets of 400 mg each) of nafithromycin, administered once daily for 3 days. The tablets were administered with 240 ml of drinking water at a consistent time within 2 h after a standard meal and under direct observation at the study site. Blood samples were collected to measure the concentrations of nafithromycin in plasma within 15 min prior to and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h following the first dose of nafithromycin. The sample collected 24 h after the first dose was collected prior to the second dose on day 2. Blood samples were collected to measure the concentrations of nafithromycin in plasma within 15 min prior to and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 36 h following the third dose of nafithromycin. Subjects scheduled for bronchoscopy at 48 h after the third dose of nafithromycin also had a blood sample collected to measure the concentrations of nafithromycin in plasma.

Each subject had one standardized bronchoscopy and BAL at either 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, or 48 h following the third dose of nafithromycin. Aliquots of BAL fluid were obtained to determine urea concentrations in BAL fluid and the cell count with differential. A blood sample was obtained at the time of the scheduled bronchoscopy to determine the plasma urea concentration. The bronchoscopy and BAL procedures and sampling preparation methods for the collection of plasma and intrapulmonary samples have been previously described (10–12).

Nafithromycin concentration determination.

The nafithromycin concentrations in plasma, the BAL fluid supernatant, and the cell pellet were assayed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) methods at Keystone Bioanalytical (North Wales, PA) (report numbers 150704, 150705, and 150706, respectively).

A total of 729 plasma samples were assayed between 14 July 2015 and 27 July 2015. All plasma samples were analyzed in 13 analytical runs. Eighty samples (10.97% of the total samples analyzed) were reassayed to evaluate the incurred sample reproducibility (ISR) of previously analyzed samples.

An LC-MS/MS method was developed and validated for the quantification of nafithromycin in human plasma. The method used protein precipitation (with acetonitrile) to isolate nafithromycin and the internal standard, clarithromycin, from human plasma. A 25-μl human plasma sample was used for sample preparation and analysis. After vortex mixing and centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to an injection vial which contained 300 μl of 0.1% formic acid in 20:80 acetonitrile-water. A total injection volume of 8 μl was used for LC-MS/MS analysis. Plasma standard curves were linear (r2 > 0.994) over the concentration range of 10.0 to 5,000 ng/ml for nafithromycin. Precision (i.e., the percent coefficient of variation) and accuracy (i.e., the percent bias) of the nafithromycin plasma standards were 2.13 to 6.60% and −4.23 to 3.35%, respectively. The precisions for quality control (QC) plasma samples at 30, 500, and 3,750 ng/ml of nafithromycin were 5.76%, 4.17%, and 2.94%, respectively. The accuracies for plasma QC determinations of nafithromycin ranged from 0.89 to 3.33%. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of the nafithromycin concentration in plasma was 10 ng/ml. The difference between the original and ISR values for nafithromycin in all of the samples selected for reproducibility testing was within 20.0%.

A total of 37 BAL fluid samples were assayed for the nafithromycin concentration in three analytical runs. The standard curve for nafithromycin in human BAL fluid was linear (r2 ≥ 0.994) over the concentration range of 1.0 to 200 ng/ml. The precision and accuracy for the nafithromycin BAL fluid standards were 0.43 to 3.51% and −6.06 to 8.91%, respectively. The precision for QC BAL fluid samples at 3, 40, and 150 ng/ml of nafithromycin were 13.60%, 2.61%, and 2.54%, respectively. The accuracy for BAL fluid nafithromycin QC determinations ranged from −5.52 to 6.83%. The LLOQ of the nafithromycin concentration in BAL fluid was 1 ng/ml. The assay variability values were within 20.0% for all 10 samples selected for ISR testing.

A total of 37 cell pellet samples were assayed for the nafithromycin concentration in three analytical runs. The standard curve for nafithromycin in cell pellets was linear (r2 ≥ 0.997) over the concentration range of 1.0 to 200 ng/ml. The precision and accuracy of the nafithromycin cell pellet standards were 1.33 to 3.70% and −4.85 to 5.36%, respectively. The precision for QC cell pellet samples at 3, 40, 150, 3,000, and 7,500 ng/ml of nafithromycin were 7.21%, 3.62%, 3.28%, 4.00%, and 2.28%, respectively. The accuracy for cell pellet QC determinations of nafithromycin ranged from −7.84 to 1.27%. The LLOQ of the nafithromycin concentration in cell pellets was 1 ng/ml. Ten samples were reassayed to evaluate the ISR, and all assay variability values were within 20.0% of the values for the samples in the previous analysis.

Urea concentration determination.

The concentrations of urea in plasma and the BAL fluid supernatant were determined using an LC-MS/MS method that was developed and validated at Keystone Bioanalytical (North Wales, PA) (report numbers 150701 and 150703, respectively). The method used protein precipitation (with methanol) to isolate urea from plasma and [13C, 15N2]urea as an internal standard for both matrices. The blank control matrix for the calibration standards was phosphate-buffered saline solution for the plasma assay and 0.9% sodium chloride for the BAL fluid assay. Human plasma or BAL fluid plus the blank control was used to prepare QC samples.

The assay was linear (r2 ≥ 0.998) for concentrations of urea in plasma and BAL fluid ranging from 100 to 3,000 μg/ml and 0.2 to 10 μg/ml, respectively. The accuracy ranges for all urea calibration standards in plasma and BAL fluid were −4.28 to 3.04% and −3.50 to 3.29%, respectively. The precision for QC samples at 207.81, 1,000, and 2,250 μg/ml of urea in plasma were 1.09%, 0.18%, and 0.41%, respectively. The accuracy for these QC samples ranged from −4.09 to 1.53%. The LLOQ for the urea concentration in human plasma was 100 μg/ml. For urea in human BAL fluid and saline, the coefficients of variation were 6.78%, 2.53%, and 2.77% for QC samples with urea at 0.6, 3.0, and 7.5 μg/ml, respectively. The accuracy for the QC samples ranged from −1.13 to 5.47%. The LLOQ of the urea concentration in human BAL fluid was 0.2 μg/ml.

Calculation of concentrations of nafithromycin in ELF and AM.

The urea dilution method described by Rennard and colleagues was used to determine the apparent volume of ELF in BAL fluid (21). The concentration of nafithromycin in ELF (NAFELF) was determined as follows: NAFELF = NAFBAL × (ureaplasma/ureaBAL), where NAFBAL is the concentration of nafithromycin in BAL fluid, ureaplasma is the concentration urea in plasma, and ureaBAL is the concentration of urea in BAL fluid. The concentration of nafithromycin in alveolar macrophages (NAFAM) was determined as follows: NAFAM = NAFpellet/VAM, where NAFpellet is the concentration of nafithromycin measured in the cell suspension and VAM is the volume of alveolar cells in the 1-ml cell suspension. A differential cell count of the BAL fluid was carried out, and the percentage of macrophages was determined. A mean macrophage cell volume of 2.42 μl/106 cells was used in the calculations for VAM (10–12).

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Noncompartmental methods were used to generate the values of pharmacokinetic parameters for nafithromycin in plasma. The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), the time to Cmax (Tmax), and the minimum plasma concentration (Cmin) were read from the observed plasma concentration-time profile following the first and third doses of nafithromycin. Cmin was the plasma concentration 24 h after the first and third doses. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) after the first and third doses was calculated with the linear-log trapezoidal rule (WinNonlin software, version 6.3; Pharsight Corporation, Cary, NC). The AUC for the first dose was extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞), and the AUC for the third dose was determined for the 24-h dosing interval (AUC0–24 or the AUC for the dosing interval ending at tau [AUC0–tau]). The elimination rate constant (β) was determined by nonlinear least-squares regression. The elimination half-life (t1/2) was calculated by dividing β into the natural logarithm of 2. For nafithromycin, the apparent clearance (CL/F) and volume of distribution (V/F) were calculated with the following equations: CL/F = dose/AUC and V/F = dose/AUC · β, where F is the fraction of bioavailability and was assumed to equal a value of 1 (100%) and where AUC was AUC0–∞ for the first dose and AUC0–24 for the third dose.

The intrapulmonary penetration of nafithromycin was estimated from the ratios of the AUC0–24 for ELF or AM to the AUC0–24 for plasma. Both the mean and median values of the plasma, ELF, and AM concentrations at the bronchopulmonary sampling times were used to estimate AUC0–24 by the linear-log trapezoidal rule. The nafithromycin concentration at the 24-h sampling time after the third dose for each matrix was also used as a time zero value for the determination of AUC0–24. In addition, the ratios of the ELF and AM concentrations to the simultaneous plasma concentrations were calculated and reviewed for each subject and summarized for each sampling time.

Laboratory and safety assessment.

Safety was monitored by clinical laboratory tests (serum chemistry, hematology, coagulation, and urinalysis), physical examination, standard 12-lead ECGs, vital sign determinations, and observation or reporting of adverse events. The investigators assessed the subjects for the occurrence of adverse events from the time that the informed consent was signed until the time that the last follow-up visit was completed. An adverse event was defined as any untoward, unfavorable, and unintended sign (e.g., an abnormal laboratory finding), symptom, or disease temporally associated with the use of nafithromycin, whether or not it was related to the treatment in the study. The population for safety analysis included all subjects who were enrolled into the study and received at least one dose of nafithromycin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Wockhardt Ltd.

Regarding conflicts of interest, K.A.R. and M.H.G. have been consultants to Wockhardt Ltd. R.C., M.G., H.D.F., and A.B. are current employees of Wockhardt Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Farrell DJ, Sader HS, Rhomberg PR, Flamm RK, Jones RN. In vitro activity of WCK 4873 (nafithromycin) against resistant subsets of Streptococcus pneumoniae from a global surveillance program (2014), abstr Saturday-455 Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubois J, Dubois M, Martel J-F. In vitro activity of a novel lactone ketolide WCK 4873 against resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, abstr Sunday-475 Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrell DJ, Sader HS, Rhomberg PR, Flamm RK, Jones RN. In vitro activity of lactone ketolide WCK 4873 when tested against resistant contemporary community-acquired bacterial pneumonia pathogens from a global surveillance program, abstr Sunday-476 Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubois J, Dubois M, Martel J-F. In vitro activity of a novel lactone ketolide WCK 4873 against resistant Legionella pneumophila, abstr Sunday-477. Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubois J, Dubois M, Martel J-F. In vitro intracellular activity of a novel lactone ketolide WCK 4873 against resistant Legionella pneumophila, abstr Sunday-479. Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waites KB, Crabb DM, Duffy LB. In vitro activities of investigational ketolide WCK 4873 (nafithromycin) and other antimicrobial agents against human mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas, abstr Sunday-480. Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohlhoff SA, Hammerschlag MR. In vitro activities of WCK 4873, a second generation ketolide, against Chlamydia pneumoniae, abstr Monday-012 Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nix DE. 1998. Intrapulmonary concentrations of antimicrobial agents. Infect Dis Clin North Am 12:631–646. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodvold KA, George JM, Yoo L. 2011. Penetration of anti-infective agents into pulmonary epithelial lining fluid: focus on antibacterial agents. Clin Pharmacokinet 50:637–664. doi: 10.2165/11594090-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodvold KA, Gotfried MH, Danziger LH, Servi RJ. 1997. Intrapulmonary steady-state concentrations of clarithromycin and azithromycin in healthy adult volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:1399–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodvold KA, Danziger LH, Gotfried MH. 2003. Steady-state plasma and bronchopulmonary concentrations of intravenous levofloxacin and azithromycin in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2450–2457. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2450-2457.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotfried MH, Danziger LH, Rodvold KA. 2003. Steady-state plasma and bronchopulmonary characteristics of clarithromycin extended-release tablets in normal healthy adults. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:450–456. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller-Serieys C, Soler P, Cantalloube C, Lemaitre F, Gia HP, Brunner F, Andremont A. 2001. Bronchopulmonary disposition of the ketolide telithromycin (HMR 3647). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:3104–3108. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.3104-3108.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadota J-I, Ishimatsu Y, Iwashita T, Matsubara Y, Tomono K, Tateno M, Ishihara R, Muller-Serieys C, Kohno S. 2002. Intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics of telithromycin, a new ketolide, in healthy Japanese volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:917–921. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.917-921.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conte JE Jr, Golden JA, Kipps J, Zurlinden E. 2004. Steady-state plasma and intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cethromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:3508–3515. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3508-3515.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodvold KA, Gotfried MH, Still JG, Clark K, Fernandes P. 2012. Comparison of plasma, epithelial lining fluid, and alveolar macrophage concentrations of solithromycin (CEM-101) in healthy adult subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:5076–5081. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00766-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatis A, Chugh R, Gupta M, Iwanowski P. 2016. Nafithromycin single ascending dose (SAD) and food effect (EF) study in healthy subjects, abstr Monday-514. Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chugh R, Gupta M, Iwanowski P, Bhatia A. Nafithromycin phase 1 multiple ascending dose study in healthy subjects, abstr Monday-513. Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bader JC, Lakota EA, Rubino CM, Patel MV, Bhagwat SS, Ambrose PG, Bhavnani SM. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) target attainment (TA) analysis to support WCK 4873 dose selection for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP), abstr Monday-507 Abstr ASM Microbe, Boston, MA American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satav J, Takalkar S, Umarkar K, Chavan R, Patel A, Bhagwat S, Patel M. 2017. WCK 4873 (nafithromycin): PK/PD analysis for H. influenzae (HI) through murine lung infection model, abstr OS1017. Abstr ECCMID, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rennard SI, Basset G, Lecossier D, O'Donnell KM, Pinkston P, Martin PG, Crystal RG. 1986. Estimation of volume of epithelial lining fluid recovered by lavage using urea as marker of dilution. J Appl Physiol 60:532–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]