Abstract

Numerous RNA-binding proteins have modular structures, comprising one or several copies of a selective RNA-binding domain generally coupled to an auxiliary domain that binds RNA non-specifically. We have built and compared homology-based models of the cold-shock domain (CSD) of the Xenopus protein, FRGY2, and of the third RNA recognition motif (RRM) of the ubiquitous nucleolar protein, nucleolin. Our model of the CSDFRG–RNA complex constitutes the first prediction of the three-dimensional structure of a CSD–RNA complex and is consistent with the hypothesis of a convergent evolution of CSD and RRM towards a related single-stranded RNA-binding surface. Circular dichroism spectroscopy studies have revealed that these RNA-binding domains are capable of orchestrating similar types of RNA conformational change. Our results further show that the respective auxiliary domains, despite their lack of sequence homology, are functionally equivalent and indispensable for modulating the properties of the specific RNA-binding domains. A comparative analysis of FRGY2 and nucleolin C-terminal domains has revealed common structural features representing the signature of a particular type of auxiliary domain, which has co-evolved with the CSD and the RRM.

INTRODUCTION

Many RNA-binding proteins have modular structures consisting of one or several copies of various selective RNA-binding domains, frequently coupled to so-called auxiliary domains (1). The RNA-binding domains can be divided into various classes, including the RNA recognition motif (RRM) class and the cold-shock domain (CSD) class (reviewed in 2). The RRM (∼90 amino acids in length and highly variable in sequence, see below) is the best characterised RNA-binding motif containing two highly conserved peptide motifs, an octapeptide and a hexapeptide called RNP-1 and RNP-2 consensus sequences, respectively. The three-dimensional structure of the N-terminal RRM of the U1A protein was the first to be determined, revealing a β1α1β2β3α2β4 folding topology (3,4). The RNP-1 and RNP-2 motifs are located on the central β3- and β1-strands, respectively, and their highly conserved aromatic residues exposed on the surface of the β-sheet constitute a potential interaction surface with RNA. Indeed the determination of the crystal structure of the complex formed between the first RRM of U1A and a 21 nt RNA hairpin derived from its cognate U1 snRNA revealed that the 10 nt RNA loop of the hairpin is bound as an open structure with two bases contacting conserved aromatic residues within the RNP-1 and RNP-2 motifs (5). More recent structural studies of other RRM–RNA complexes have also identified the β-sheet region as the binding site for RNA (6–8).

In contrast to the RRM, the CSD is the most conserved of the nucleic acid-binding domains, able to bind both single-stranded DNA and RNA (reviewed in 9). This domain is named after the 70 amino acid prokaryotic cold-shock protein (Csp) and is a key component of the eukaryotic Y-box family of proteins, where it is coupled to auxiliary domains (10). Following the report by Landsman (11) that the RNP-1 motif, the hallmark of the RRM, is also present in the CSD, analysis of the three-dimensional structures of two prokaryotic cold-shock proteins, CspA and CspB, placed the RNP-1 and RNP-2 motifs on adjacent β-strands of the CSD ‘β1β2β3β4β5’-type structure (12–15). This suggested that there might be spatial conservation of potential nucleic acid-binding surfaces between the RRM and the CSD (12). Furthermore, mutational studies demonstrated the involvement of aromatic residues of CspB RNP-1 and RNP-2 motifs in binding single-stranded DNA (16).

Another common feature shared by the RRM- and CSD-types of specific RNA-binding domains is their frequent coupling to auxiliary RNA-binding domains. This modular organisation is illustrated on the one hand by nucleolin, a ubiquitous abundant nucleolar protein which comprises four RRMs and one C-terminal Gly-Arg-rich ‘GAR’ domain (reviewed in 17), and on the other hand by FRGY2 (also called mRNP4), a Y-box protein from Xenopus laevis and a major component of ribonucleoproteic storage particles that comprises one CSD and one ‘basic/aromatic (B/A)-island’ containing C-terminal domain (18,19). In the present report, we focus in depth on the functional and structural similarities between the CSD and the RRM, taking as examples the CSD of FRGY2 and the third RRM of nucleolin. We use computer modelling to show how the structural similarity between these two domains affects the way they recruit the single-stranded region of their respective specific RNA targets. The RNA-binding properties of both the RRM and CSD domains are evaluated using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. We have then investigated the parallel roles of the respective auxiliary domains, which are coupled to these two RNA-binding domains, in the context of their integrated functions within the two proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of recombinant polypeptides

The coding DNA sequences corresponding to the third RRM of nucleolin, RRM3NUC, and the CSD of FRGY2, CSDFRG, were generated by PCR using Vent™ DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) and either hamster nucleolin cDNA (20) or FRGY2 cDNA (21) as templates. The primer oligonucleotide sequences were as follows: R3N, CCCCATATGACTTTGGTTTTAAGTAAC; R3C, CCCGGATCCGGTACCTTGTAACTCCAACCTGAT; CSN, GCCGCGGCATATGCGAAACCAGGCCAAC; CSC, TGGGACCCCGGATCCTGGGCCCGTCAC. PCR products contain NdeI and BamH1 sites at their 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively, used for subcloning into the corresponding sites of the pET-15b plasmid (Novagen). The BL21(DE3) plysS Escherichia coli strain was transformed with each recombinant pET-15b plasmid. The expression and purification of the two recombinant polypeptides were performed as previously described (22).

Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX)

A pool of RNAs were prepared by transcription from a set of random N25 oligodeoxynucleotides (Fig. 1A) as previously described (19,23). Five micrograms of N-terminal His-tagged RRM3NUC or CSDFRG were mixed with 2 µl Ni2+–NTA beads in NT2 buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM MgCl2). In a typical cycle of selection, 500 ng of random RNA were incubated with 5 µg of His-tagged RRM3NUC or CSDFRG bound to Ni2+–NTA beads for 10 min in 100 µl of reaction mixture [20 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 2.5% polyvinyl alcohol, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 µg/ml poly(A), 2 µg/ml vanadyl ribonucleoside complex, 0.5 mg/ml tRNA, 125 µg/ml bovine serum albumin, 80 U/ml RNasin (Promega)].Following incubation, the beads were washed five times with NT2 buffer, and bound RNA molecules were phenol extracted and precipitated. Reverse transcription and PCR were performed as previously described (19,23). The selection by RRM3NUC and CSDFRG resulted from 10 and 6 cycles, respectively. After the final PCR, the cDNAs were digested with XbaI and HindIII and subcloned in pSP64pA (Promega) for sequencing.

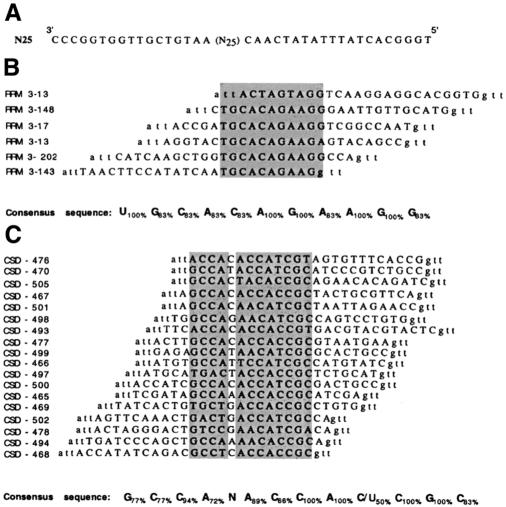

Figure 1.

RNA sequences selected from a pool of randomised 25mers by RRM3NUC and CSDFRG. (A) Sequence of the oligodeoxynucleotide used to generate the pool of random RNA transcripts. (B and C) Alignments of the sequences of the DNA fragments resulting from the retrotranscription of the aptamer RNAs selected by either RRM3NUC (B) or CSDFRG (C). In each case the corresponding SELEX RNA consensus sequence is indicated below the alignment.

CD

CD spectra were recorded at 20°C with a Jobin-Yvon VI dichrograph. A cell of 1 cm optical path length was used to record spectra of RNA and polypeptide–RNA complexes at an RNA concentration of 10 µg/ml in 0.15 M NaCl/20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4 in the near-ultraviolet region (320–220 nm). The results are presented as normalised Δɛ values on the basis of the nucleotide mean residue mass of 330 Da. Taking into account the sensitivity of the apparatus [Δ(ΔA) = 10–6], the nucleotide concentration and the optical path length of the cell, the precision of the measurements is Δ(Δɛ) = ±0.03 dm3 mol–1 cm–1. A cell of 1 mm optical path length was used to record spectra of polypeptides at a peptide concentration of 0.2 mg/ml in 0.15 M NaCl/20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4 in the UV region (260–190 nm). Above this polypeptide concentration the solution became turbid. The results are presented as normalised [θ] values on the basis of the amino acid mean residue mass of 110 Da. The precision of the measurements is Δ([θ]) = ± 20 deg cm2 dmol–1.

Molecular modelling

Models were generated using the MSI Technologies, Inc. (San Diego, CA) modules INSIGHTII, BIOPOLYMER, DISCOVER, CHARMM, DOCKING and HOMOLOGY (version 98), run on Silicon Graphics O2 workstations.

Homology modelling of the two RNA-binding domains was performed according to the main principles outlined by Greer (24) with a special emphasis on the initial step of templates structural alignments. This provided an accurate definition of the structurally conserved regions (SCRs) within each domain family [the overall root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) being <1.2 Å]. Based on the level of sequence identity, the second RRM of sex-lethal protein and the major cold-shock protein of E.coli were identified as the best references to build the respective models of RRM3NUC and CSDFRG. The sequences of RRM3NUC and CSDFRG were aligned with those of their corresponding templates, allowing the assignment of the SCRs. Gap assignment was assisted by the information resulting from the structural alignments. The main modelling steps involved the transfer of co-ordinates between SCRs, the building of loops and a final structural refinement by energy minimisation applied to the most critical regions (junctions between SCRs and loops, mutated side chains in SCRs and loops). Energy minimisation was performed with the steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms, down to a maximum derivative of 0.01 kcal/Å using the Discover consistent valence force field ‘cvff’ and a forcing constant of 100 kcal/mol. The validity of the two models was assessed both by ‘structural check’ and ‘folding consistency verification’ using the Prostat (25,26) and Profiles_3D (27) programs, respectively, within the Homology module. No spurious angle, bond length or misfolded region was detected. The percentages of the so-called ‘most favoured regions’ in the Ramachandran plots were 83% for CSDFRG (relative to 87% for the template 1MJC) and 81% for RRM3NUC (relative to 84% for the template 3SXL).

Using ‘mfold’ version 3.0 (28), we predicted that both RNA consensus sequences adopt a single-stranded conformation for all the RNAs recruited by either RRM3NUC or CSDFRG. We then modelled two single-stranded RNA fragments, UGCACAGAAGG and GCCAUAACAUCGC, corresponding to the consensus regions in RRM 3-17 and CSD-499 RNA, respectively.

Docking of the RNAs (RRM 3-17 RNA and CSD-499 RNA) into their respective RNA-binding domains (RRM3NUC and CSDFRG) was performed using the Affinity program within the Docking module. Affinity is an energy-based method, which uses a Monte Carlo procedure in conjunction either with energy minimisation [to mimic the method by Li and Scheraga (29)] or with molecular dynamics and simulated annealing. Affinity allows predefined atoms of the ‘ligand’ (RNA) and the ‘binding site’ (RNA-binding domain) to relax during docking. We initially ‘pre-docked’ the RNAs into their respective RNA-binding domains by pre-positioning 2 nt, either adjacent (5′i, 3′i+1) or 1 nt apart (5′i, 3′i+2), at an approximate stacking distance from the two corresponding RNP-2 and RNP-1 conserved aromatic/hydrophobic amino acids. Each nucleotide pair was considered. Using Monte Carlo minimisation we screened these initial complexes in turn for their capacity to converge to a final structure offering both the best stacking interaction and the minimum energy complex. The parameters of the minimisation were 20 cycles of 1000 minimisation steps using the Cell_Multipole method as a non-bond summation procedure and convergence criteria of 10 kcal/mol as the energy test and 1 Å as the r.m.s.d. tolerance threshold. In the case of the selected RRM3NUC–RNA complex, the final interaction energy was –85 kcal/mol for the van der Waals component and 28 kcal/mol for the electrostatic component. In the case of the selected CSDFRG–RNA complex, the final interaction energy was –80 kcal/mol for the van der Waals component and 17 kcal/mol for the electrostatic component. Simulated annealing was then applied for each respective selected complex. No major change was observed after 50 stages of 100 fs, the initial and final temperatures being 500 and 300 K, respectively. The comparison of the structures before and after simulated annealing gave r.m.s.d. values of 0.1 Å for the RNA-binding domain and 0.3 Å for the RNA in each case.

The three-dimensional models of the motifs characteristic of the auxiliary domains were initially based on extended structures. These structures were then further refined through successive cycles of energy minimisation and molecular dynamics using the ‘charmm22’ force field (30). The target temperature was 300 K, the durations of the heat, equilibration and simulation phases were 3, 7 and 2 ps, respectively, with femtosecond steps.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RRM3NUC and CSDFRG as model systems for studying functional RRM- and CSD-type RNA-binding domains

RNA-binding selectivity. Nucleolin possesses three distinct domains, a 280 amino acid long N-terminal domain, which is able to modulate chromatin condensation (31,32), a central domain of 350 amino acids comprising four consensus RRMs and a C-terminal GAR domain, 85 residues long, rich in glycine interspersed with arginine and phenylalanine residues (33). We have previously shown that the RRMs and the auxiliary GAR domain function in synergy to efficiently package pre-ribosomal RNA (34). Several sites of interaction between nucleolin and pre-rRNA have been mapped within the 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA sequences as well as in the 5′-external transcribed spacer (5′-ETS) (35). A detailed study of the 5′-ETS interaction sites has been performed, leading to the identification of two phylogenetically conserved RNA motifs, which can be correlated with two respective RNA sequence families obtained by a selection–amplification (SELEX) approach (36,37). On the one hand, we have shown that the polypeptide corresponding to the first two RRMs of nucleolin is necessary and sufficient for the specific recognition of the ‘UCCCGA’ motif located in a stem–loop structure (the so-called ‘nucleolin-responsive element’, NRE) (22,38). The three-dimensional structure of the resulting complex in solution has recently been determined (39). On the other hand, the synergy of the four nucleolin RRMs is essential for the specific recognition of the ‘UCGA’ motif within a single-stranded RNA fragment (the so-called ‘evolutionary conserved motif’, ECM) (40). This shows that nucleolin uses at least two different combinations of its RRMs to determine RNA-binding specificity (note that the Kd for the ECM is 100 nM as compared to 5–20 nM for the NRE).

In contrast to RRM-1, RRM-2 and RRM-4, specific RNA recognition can be demonstrated for the third RRM of nucleolin when isolated from the other domains. In vitro selection–amplification experiments using pools of random 25 nt RNA sequences identified a SELEX consensus sequence ‘UGCACAGAAGG’, which preferentially binds to RRM3NUC (Fig. 1B). Additional investigation, beyond the scope of the present study, is needed to relate this SELEX sequence to the SELEX sequence families identified by the entire nucleolin, as well as to one of the potential pre-rRNA binding sites. In the context of a comparative study of the RRM and the CSD, this particular nucleolin RRM offers the clear advantage of being able to form a specific binary complex with RNA.

In common with all Y-box proteins, the X.laevis protein FRGY2 contains a highly conserved domain, the CSD, that is 42% identical to the sequence of the bacterial cold-shock protein (18). Bouvet et al. (19) showed, using a SELEX approach, that FRGY2 is able to specifically recognise RNA sequences whose consensus is ‘AACAUCU’. Through a mutation/deletion analysis of the protein, these authors were able to ascribe this capacity to the CSD. In experiments using purified FRGY2 CSD and the same degenerate pool of in vitro transcripts used previously with RRM3NUC, we now show directly that CSDFRG selects RNA sequences whose bipartite consensus is ‘GCCA N AC(/A)CAC(/U)CGC’ (Fig. 1C). The second part of this sequence is clearly related to the previously described FRGY2 SELEX consensus sequence.

The affinities of RRM3NUC and CSDFRG for their respective selected RNA sequences were evaluated by filter binding assays as previously described (36) and shown to be at least one order of magnitude higher than that for non-specific RNA (data not shown). The apparent Kd values of these interactions were estimated to be in the sub-micromolar range for both types of domains. Similar Kd values (0.3–0.9 µM) were reported in the case of CspE and CspB for their respective SELEX RNA sequences whilst CspC has a 10-fold lower binding affinity for its SELEX sequence (41). This underlines the functional homology in terms of RNA-binding capacities between these cold-shock proteins from E.coli and certain eukaryotic CSDs. The affinity of RRM3NUC for its selected RNAs is in the range of the Kd values reported for known specific RRM–RNA complexes. This relatively large range of Kd values is best illustrated by the RRM-containing hnRNP A1 protein, which recognises different RNA sequences with a >100-fold range of affinities (2).

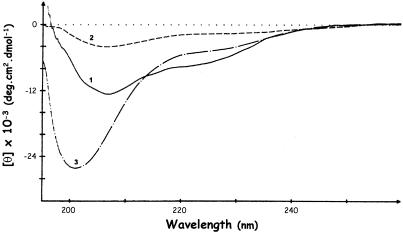

Domain topology. CD is a sensitive tool to probe protein supersecondary structure and is capable of distinguishing between ‘all-α’, ‘all-β’, ‘α+β’ and ‘α/β’ proteins, as shown by Manavalan and Johnson (42). In the CD spectrum of RRM3NUC (Fig. 2, curve 1), the band at 208 nm and the shallow minimum around 222 nm indicate the presence of separate α-helical and β-sheet regions typical of ‘α+β’ proteins, consistent with the supersecondary structure of a classical RRM. Such spectra have also been reported for polypeptides comprising either all four RRMs of nucleolin together (34) or only the first two RRMs (22). In contrast, and in line with the canonical CSD, the low intensity CD spectrum of CSDFRG (Fig. 2, curve 2) presents the characteristic features of one type of an ‘all-β’ protein such as pepsinogen (43). Taken together, our CD analysis is consistent with the folding of both RRM3NUC and CSDFRG in topologies typical of their respective RNA-binding domain families.

Figure 2.

CD assessment of polypeptide folding. CD spectra of RRM3NUC (curve 1), CSDFRG (curve 2) and FRGY2 (curve 3).

Structural and functional analogies between the CSD and the RRM

Although there is circumstantial evidence that the RNA-binding surface of CSD is similar to that of RRM, no direct structural evidence is available. With this goal in mind, we have made use of a computer modelling approach, taking advantage of recent technical advances in comparative modelling and molecular docking. We initially describe the construction of the two individual RNA-binding domains and then examine docking with their respective single-stranded RNA targets.

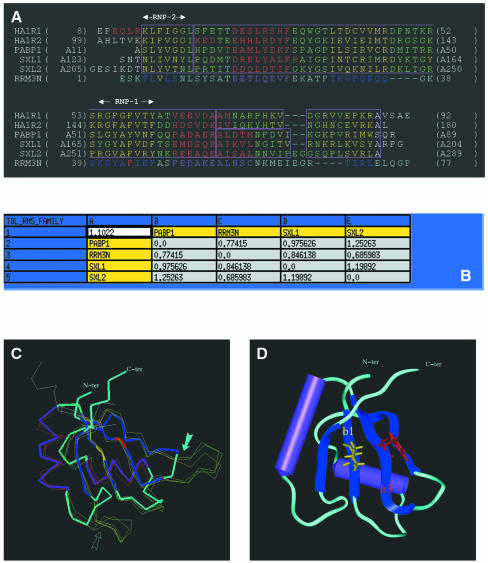

Computer-modelling of the three-dimensional structures of the RRM3NUC and CSDFRG domains. Structural alignment of template proteins is a crucial step in homology modelling since it allows a better definition of the boundaries of the SCRs. This is especially important when the overall sequence homology between family members is relatively low, as is the case for the RRMs (∼30%). Atomic co-ordinates are now available for a number of high-resolution RRM structures, either in isolation or in complex with their respective RNA targets (5–8,44,45). We built structural alignments of RRMs using the crystallography-derived atomic co-ordinates of the following seven RRMs: the first RRM of U1A, the two RRMs of hnRNPA1, the first two RRMs of PABP and the two RRMs from the sex-lethal protein, with respective Protein Data Bank (PDB) accession nos 1URN (5), 2UP1 (7), 1CVJ (6), 1B7F (8). Applying stringent criteria of structural similarity (r.m.s.d. of 1.2 Å as the upper limit for the overall r.m.s.d. calculated at the level of the SCRs), we were able to accurately align five out of the seven initial RRM templates (Fig. 3A). This defines one main structural family which itself comprises two sub-families depending on the length of the second helix in the domain. Interestingly, the first RRM of U1A as well as the second RRM of PABP had to be excluded from these alignments, indicating that they belong to other RRM structural sub-families. Based on the level of sequence identity, the second RRM of sex-lethal protein was identified as the best reference with which to build the model of RRM3NUC. The sequence of RRM3NUC was thus aligned with that of its template, allowing the assignment of the SCRs. We made use of the structural alignment in assigning gap positions when aligning the two proteins sequences. The resulting model for the structure is displayed in Figure 3C and D (see Materials and Methods for a detailed account of the model building and structural check protocols). The r.m.s.d. value between the modelled RRM3NUC structure and that of its template SXL2 is 0.7 Å (Fig. 3B). Approximately the same r.m.s.d. values are found when a pairwise comparison is made with the structures of the other two RRMs of the same sub-family (PABP1 or SXL1; Fig. 3B, line 3 or column C). The main distinctive features of RRM3NUC are the two shorter loops between the β2- and β3-strands and between the α2-helix and β4-strand, respectively (Fig. 3C, solid and outlined arrows, respectively). Within the RRM consensus fold, the conserved RNP-1 and RNP-2 motifs corresponding to the β3- and β1-strands, respectively, are spatially adjacent and include the two most conserved hydrophobic/aromatic RRM residues. The corresponding RRM3NUC side-chains have been highlighted in red (Phe) and in yellow (Val) (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Homology modelling of RRM3NUC. (A) Structural alignment of RRMs as explained in Materials and Methods: HA1R1 and HA1R2 are the two RRMs of hnRNPA1, PABP1 is the first RRM of PABP and SXL1 and SXL2 are the two RRMs of the sex-lethal protein. Colour-coded boxes (outlined in magenta) indicate the SCRs. The secondary structure elements of these RRMs have been colour-coded (β-strands, yellow; helices, red). The sequence of the third RRM of nucleolin (RRM3N) has been aligned with that of SXL2. (B) Table of pairwise structural similarities estimated from r.m.s.d. values expressed in Å. The overall r.m.s.d. value (1.1 Å) calculated for the whole RRM sub-family is displayed at the top left corner of the table. (C) Superimposition of the traces (Cα) of the crystallographic structures of the templates (narrow lines) and the modelled structure of RRM3NUC (thick line). The same colour-coding is used as in the alignment (A). The two arrows point to distinctive features of RRM3NUC (see text). (D) Homology-derived model of RRM3NUC. The six structurally conserved elements ‘β1α1β2β3α2β4’ are similarly colour-coded (helices, purple; β-strands, blue) as in the three-dimensional model and in the alignment (A). Amino acid side chains are shown for the pair of conserved aromatic/hydrophobic residues: Phe44 (red) from RNP-1(/β3-strand) and Val6 (yellow) from RNP-2(/β1-strand). Colour-coding for these two residues is the same as in the alignment (A).

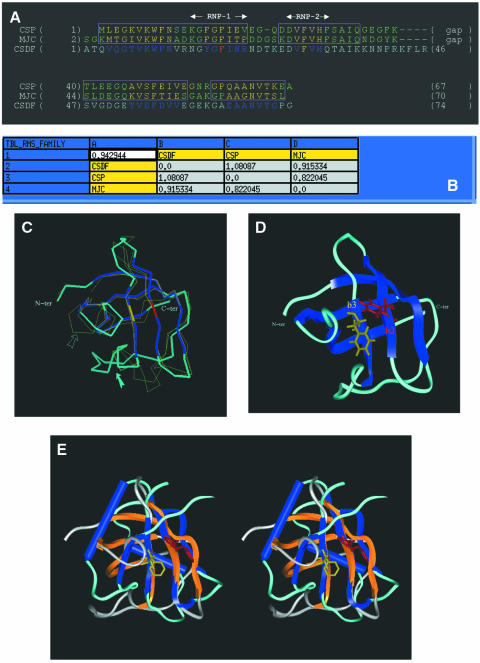

The degree of sequence homology within the CSD family is much higher (up to 60% identity) as compared with the RRM family. High-resolution structures for the major cold-shock protein from E.coli (CspA) and for the cold-shock protein from Bacillus subtilis (CspB) have been determined and lead to a straightforward structural alignment illustrated in Figure 4A. The atomic co-ordinates of CspA served as a template to model build CSDFRG and the resulting model is displayed in Figure 4C and D (see Materials and Methods for a detailed account of the model building and structural check protocols). The r.m.s.d. values between the predicted CSDFRG structure and those of either its template ‘MJC’ (/CspA) or the other member of the family ‘CSP’ (/CspB) are 0.9 and 1 Å, respectively (Fig. 4B, line 2 or column B). The main distinctive feature of CSDFRG is a longer loop between the β3- and β4-strands as compared with CspA and CspB (Fig. 4C, solid arrow). The general flexibility of the loop between β4 and β5 is highlighted (Fig. 4C, outlined arrow). As for the RRM fold, the two conserved RNP-1 and RNP-2 motifs of CSDFRG are spatially adjacent, and this time located on the β2- and β3-strands. Furthermore, two highly conserved aromatic residues (2 × Phe) are present within these motifs and, as for the RRM, these have been colour-coded in red and yellow (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Homology-derived model of CSDFRG. (A) Structural alignment of the cold-shock proteins from B.subtilis (CSP) and from E.coli (MJC). The same colour-coding as in Figure 3 has been used for the SCR boxes and for the secondary structure elements of the proteins. The sequence of CSDFRG (CSDF) has been aligned with that of MJC. (B) Table of pairwise structural similarities estimated from r.m.s.d. values expressed in Å. The overall r.m.s.d. value (0.9 Å) calculated for the whole CSD sub-family is displayed at the top left corner of the table. (C) Superimposition of the crystallographic structures of the templates and the modelled structure of CSDFRG.. The two arrows point to distinctive features of CSDFRG (see text). (D) The five conserved elements ‘β1β2β3β4β5’ of the secondary structure of CSDFRG are similarly colour-coded (blue) in the three-dimensional model as in the alignment (A). Amino acid side chains are shown for the most conserved aromatic residues: Phe19 (red) from RNP-1(/β1-strand) and Phe30 (yellow) from RNP-2(/β3-strand). Phe19 and Phe30 are colour-coded according to the sequence alignment (A). (E) Stereo-view of the two domains following superimposition of their respective RNP-1 motifs. Colour-coding: RRM3NUC β-strands and α-helices, blue; RRM3NUC loops, turquoise; CSDFRG β-strands, orange; CSDFRG loops, grey.

We next asked whether the three-dimensional topologies of RRM3NUC and CSDFRG are able to generate similar potential single-stranded RNA-binding surfaces despite both the low degree of sequence homology and significant differences in the supersecondary structure (‘β1α1β2β3α2β4’ versus ‘β1β2β3β4β5’) of the two domains. To evaluate this we attempted to superimpose the backbones of the respective homologous RNP-1 motifs (KGYAFIEF corresponding to the RRM3NUC β3-strand and NGYGFINR corresponding to the CSDFRG β2-strand). Strikingly, the superimposition of the RNP-1 motifs (r.m.s.d. = 0.9 Å) brings into remarkable register the spatially adjacent RNP-2 motifs (Fig. 4E). This underlines the structural similarity between the two potential RNA-binding surfaces.

Computer modelling of the three-dimensional structures of the complexes between the RRM3NUC and CSDFRG domains and their respective single-stranded RNA targets. Folding predictions for the SELEX consensus RNA sequences selected by RRM3NUC and CSDFRG indicate thatthey both correspond to single-stranded RNA regions (data not shown). This is consistent with the fact that the CSD generally interacts with single-stranded RNA, also a major determinant in the first step of the RRM-mediated recognition process. We thus modelled the consensus sequences U1G2C3A4C5A6G7A8A9G10G11 and G1C2C3A4U5A6A7C8A9U10C11G12C13 from RRM 3-17 RNA and CSD-499 RNA, respectively, in a single-stranded conformation and docked them into their respective protein domains.

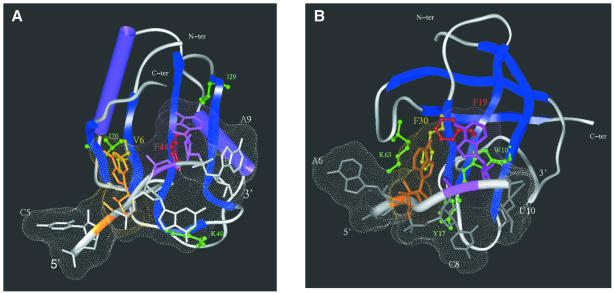

A common feature present in all the RRM–RNA complexes studied so far is a stacking interaction between the RNP-1/RNP-2 conserved aromatic(/hydrophobic) residues and 2 RNA nt, either adjacent or 1 nt apart (5–8). We therefore performed a systematic search for a suitable stacking interaction between 2 nt and the two critical residues (Phe and Val) of RRM3NUC. Using a docking protocol described in detail in Materials and Methods, we identified a favourable low energy complex involving stacking between the RNP-1 Phe44 and the RNP-2 Val6 and nucleotides A8 and A6, respectively (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, each of these stacking interactions is reinforced by the presence of a conserved hydrophobic residue, Ile29 and Ile70 located at a stacking distance from A8 and A6, respectively. Moreover, C7 is stacked with the aliphatic portion of the K40 side chain. Note that amino acid substitutions at this position in the RRM structural alignment (K replaced by R, L or Y) conserve the potential for hydrophobic stacking (Fig. 3A).

Figure 5.

Modelling of the interaction between RRM3NUC and CSDFRG and their specific single-stranded RNAs. (A) Docking of RRM3NUC with the RRM 3-17 RNA. Note the two pairs of stacked residues: RNP-1 Phe44/A8 (red/mauve, respectively) and RNP-2 Val6/A6 (yellow/brown, respectively). Additional important residues are green-coded (see text). (B) Docking of CSDFRG with the CSD-499 RNA. Note the two pairs of stacked residues: RNP-1 Phe19/A9 (red/mauve, respectively) and RNP-2 Phe30/A7 (yellow/brown, respectively). Additional important residues are green-coded as in (A) (see text). In both complexes the Connolly surface of the RNA has been calculated (shown as small dots).

Similarly, we were able to identify an analogous low energy complex involving stacking between the RNP-1 Phe19 and the RNP-2 Phe30 of CSDFRG and nucleotides A9 and A7, respectively, of the corresponding single-stranded RNA (Fig. 5B). The comparative analysis between the respective binding interfaces of the two complexes identifies analogous conserved hydrophobic clusters involving the stacking of W10, K63 and Y17 with A9, A7 and C8, respectively. Finally, both RNAs adapted their structures to their respective proteic surfaces as previously observed for a variety of RRM–RNA complexes (6,8). On the other hand, no significant conformational change in the protein component could be detected after docking in either case. A further example of RNA adaptability is illustrated by the study of the interaction between mRNA and the ribosomal protein S15 (46).

Our model of the CSDFRG–RNA complex constitutes the first three-dimensional prediction of the structure of a CSD–RNA complex. Our results highlight the analogy between the CSD and the RRM with respect to the first step of single-stranded RNA specific recognition. In both cases, the selection of a pair of nucleotides is made possible by the precise positioning of spatially adjacent aromatic/hydrophobic β-strand motifs. Strikingly, the extent of structural conservation for the [RNP-1/RNP-2]-based interaction surface between RRM and CSD (Fig. 4E) is as high as between two RRMs. Moreover, in certain cases, this interaction surface is the only structural element that can be adequately superimposed (with a r.m.s.d. value <2 Å) between RRMs. For example, this is the case for the structural alignments of RRM-1 and RRM-2 of nucleolin, either between each other or with the modelled structure of RRM3NUC. In conclusion, our findings support the hypothesis of the convergent evolution of CSD and RRM towards a similar single-stranded RNA-binding surface.

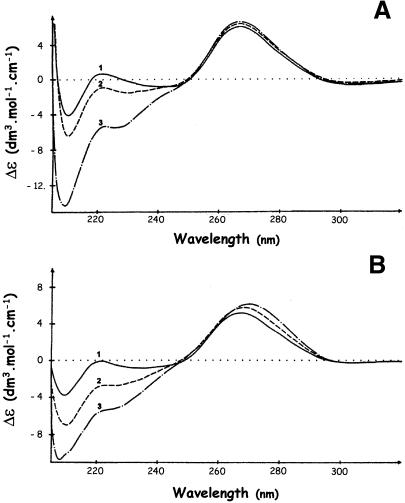

Similarities in RNA conformational changes induced by RRM and CSD binding

CD spectroscopy has been used extensively in the study of protein–DNA/RNA interactions since two distinct wavelength windows provide information about the conformation of each of the partners in nucleoprotein complexes (reviewed in 47). In the 210–230 nm range, CD spectra are dominated by the amidic contributions of the protein backbone, whereas, in the spectral region above 240 nm, nucleic acids have strong CD bands by comparison with the comparatively weak bands of the protein aromatic side chains. CD has been used both in the study of RNA secondary structure perturbations and in the characterisation of various states of RNA condensation (47). As can be seen in Figure 6A, the interaction between RRM3NUC and the specific RRM 3-17 RNA (Fig. 1B, line 3) causes an increase in Δɛ at 265 nm from 5.82 ± 0.03 to 6.55 ± 0.03. A similar effect, i.e. an increase in Δɛ at 265 nm from 5.30 ± 0.03 to 6.00 ± 0.03, is obtained when the specific CDS-499 RNA (Fig. 1C, line 9) is complexed with CSDFRG (Fig. 6B). In both cases, maximum effects are observed at 1:1 polypeptide/RNA stoichiometries. This increase in CD signal indicates a local increase in either intra- or intermolecular nucleotide stacking. We consider intramolecular stacking as unlikely since the interaction of both domains with their single-stranded RNA targets is more likely to lead to unstacking, at least at the binding sites (Fig. 5A and B). On the other hand intermolecular stacking could arise from interactions between RNA molecules brought into close proximity by the multimerisation of the associated CSD or RRM. Significantly, this property is shared by both isolated domains (data not shown). The fact that we observed similar effects of RRM3NUC and CSDFRG on non-specific RNAs (in this case at a 3-fold higher protein/RNA stoichiometry, in line with the lower affinities of the domains for these RNAs; data not shown) lends support to the hypothesis that a relatively non-specific phenomenom such as domain multimerisation may be the cause of RNA packaging. Moreover, ordered arrays of complexes between poly(A) and the first two RRMs of PABP have been observed (6). Since packaging of stored maternal mRNA in Xenopus oocytes is likely to be one key function of FRGY2 (48) and packaging preribosomal RNA into ‘exportable’ RNP particles is probably an important function of nucleolin (17), this would be consistent with a role for both domains as potential effectors of RNA packaging. However, it is now essential to extend this study to include the key relationship, which has evolved between these two domains and their so-called ‘auxiliary’ RNA-binding domains.

Figure 6.

CD analyses of the interactions between RRM3NUC, CSDFRG and their respective SELEX RNA targets. (A) Interaction between RRM3NUC and RRM 3-17 RNA. (B) Interaction between CSDFRG and CSD-499 RNA. In both cases, the polypeptide/RNA stoichiometries were: 0 (curves 1); 0.3 (curves 2); 1 (curves 3).

Nucleolin and FRGY2 auxiliary domains are equivalent modulators of RNA conformation

We have previously shown that the Gly-rich C-terminal domain of nucleolin is structured in repeated β-turns, centred on a repeat motif RGGF, and leading to a non-specific interaction with RNA in which the RNA is unstacked (33). Another important property of this domain is its capacity to significantly modify the RNA-binding properties of nucleolin’s central core (34). When the polypeptide comprising the four RRMs of nucleolin interacts with RNA, the resulting complex appears as long fibres when viewed under the electron microscope and has a CD spectrum characteristic of a highly condensed form of RNA. Such a condensed form was never observed in the case of complexes between RNA and either the complete nucleolin or a polypeptide comprising the four nucleolin RRMs and the C-terminal domain. This implies that the nucleolin C-terminal GAR domain is indispensable for orchestrating an ordered interaction with nucleolar RNA. Note that the GAR domain, also referred to as the RGG-box domain, is contained in a number of nucleolar proteins (49).

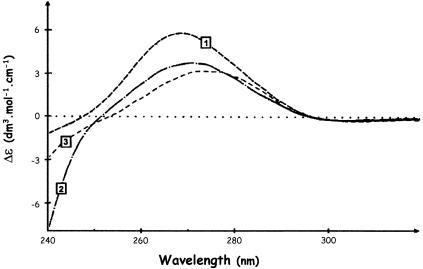

The FRGY2 protein also has a modular structure comprising the N-terminal CSD and a C-terminal domain, which interacts with RNA (50) without showing any apparent sequence specificity (19). A characteristic feature of this domain is that it contains stretches of basic and aromatic amino acids, B/A-islands (18). An alignment of the FRGY2 C-terminal domain with homologous domains from various CSD-containing proteins also reveals a significant proportion of conserved glycine, proline and glutamine residues (50). Strikingly, a secondary structure prediction of the 240 amino acid FRGY2 C-terminal domain indicates a total lack of α-helices and β-strands and points to an ‘only-loop’ structure [based on ‘PredictProtein’ (51)]. Furthermore, the CD spectrum minimum of the entire FRGY2 protein (Fig. 2, curve 3) is shifted towards 200 nm by comparison with that of the CSD spectrum (Fig. 2, curve 2) and displays a shallow minimum at 230 nm. These two CD spectral features are diagnostic for the presence of poly(l-proline) II (PPII) helix (52).

The CD spectrum of the complex between the whole FRGY2 protein and the specific CSD-499 RNA (Fig. 7, curve 2; Δɛmax = 3.25 ± 0.03) is quite different both from that of the CSDFRG–CSD-499 RNA complex (Fig. 7, curve 1; Δɛmax = 6.00 ± 0.03) and from that of free RNA (Fig. 6B, curve 1; Δɛmax = 5.30 ± 0.03). On the other hand it is similar to those observed for complexes between RNA and either the whole nucleolin or its C-terminal domain (33,34). These latter are characterised by a decrease of the free RNA maximum Δɛ value at 265 nm, accompanied by a slight red-shift of this maximum, indicating a certain degree of base unstacking as well as RNA packaging in nucleoproteic particles. This argues that the FRGY2 C-terminal domain is able to modulate the RNA conformation induced by its CSD, just as the C-terminal domain of nucleolin influences the interaction between the RRM central core and target RNA. Thus, despite their lack of sequence homology, nucleolin and FRGY2 auxiliary domains may play similar roles within each of the two proteins. Further evidence in favour of this comes from the fact that the nucleolin C-terminal domain, acting in trans, modulates RNA unstacking and packaging in a manner comparable to that of the C-terminal domain of FGRY2 itself (Fig. 7, compare curve 2 with curve 3).

Figure 7.

Modulation of RNA condensation by auxiliary domains analysed by CD. Curve 1, CD spectrum of the CSDFRG–CSD-499 RNA complex in the spectral window characteristic of RNA; curve 2, interaction between FRGY2 and the same specific RNA; curve 3, CD spectrum of the CSDFRG–CSD-499 RNA complex after addition of the C-terminal domain of nucleolin; polypeptide/RNA ratio of 1 in all cases.

This hypothesis is in line with the conclusion reached by Matsumoto et al. (53) concerning the respective roles played by the two domains of FRGY2 in translational repression (masking) of mRNA in Xenopus oocytes on the basis of both in vitro and in vivo assays. These authors have demonstrated that the sequence-selective recognition of RNA by the CSD only enhances translational repression of mRNA by FGRY2, whereas the relatively non-specific interaction of the C-terminal domain with mRNA is in fact essential for this activity. In other words, RNA conformational changes induced by the C-terminal domain of FRGY2 are dominant and likely to be the most significant from the functional point of view. It has been proposed that there is a correlation between RNA packaging and the repression of translation. Interestingly, FRGY2 and nucleolin, both with the potential to package RNA, are present within the large translation regulatory particle isolated by Yurkova and Murray (54).

Our results suggest that RNA stacking and packaging regulation may now be added to the list of reported roles of auxiliary domains in processes as varied as strand annealing, protein–protein interactions, nuclear localisation and in vitro splicing (1,55). We propose that this particularly successful coupling between both types of RNA-binding domains, specific and auxiliary, provides the corresponding proteins with a fine-tuning mechanism, which likely explains their dual ability to inhibit or enhance translation according to the cellular context (56).

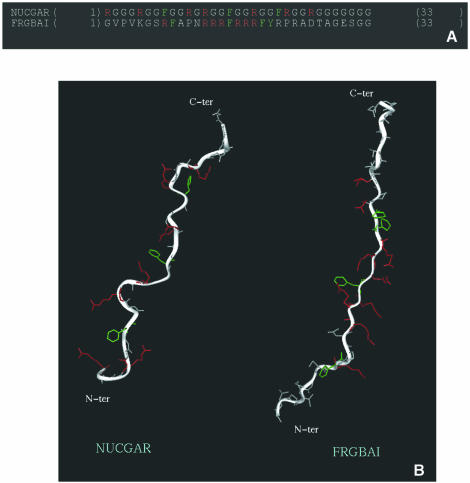

Common features of auxiliary domains associated with the RRM and the CSD

As stated above, structure prediction indicates the absence of α-helical or β-strand regions in the FRGY2 C-terminal domain and CD analysis points to an extended PPII helix-like conformation, previously shown to be the case for the nucleolin C-terminal GAR domain (33). The similarity in RNA-binding properties between the auxiliary domains of nucleolin and FRGY2 presumably correlates more with their structural similarity than with their sequence homology. Indeed, the predicted three-dimensional structures of motifs characteristic of each domain suggest both similar flexibility of the peptide backbone and accessibility of the key arginine and aromatic residues necessary for RNA binding (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Structural similarities between auxiliary C-terminal domains of nucleolin and FRGY2. (A) Sequences of motifs characteristic of each domain: ‘NUCGAR’ designates one portion of the CHO nucleolin GAR domain (PIR: A27441; residues 669–701) and ‘FRGBAI’ the first B/A-island of the X.laevis FRGY2 C-terminal domain (SWISS-PROT: P21574; residues 113–145). (B) Three-dimensional structure models of these motifs (see Materials and Methods).

We then examined whether the common features shared by the FRGY2 and nucleolin C-terminal domains are also found in other auxiliary domains. In particular, if the nucleolin GAR domain and FRGY2 B/A-islands are functionally equivalent cassettes, it should be possible to find proteins containing a CSD coupled to a GAR domain. This is indeed the case, since a protein involved in planarian regeneration, DjY1, contains a single CSD in association with RG repeat motifs (57). A second protein, Trypanosoma brucei RBP16, is a recently identified mitochondrial Y-box family protein with guide RNA binding activity (58). RBP16 comprises a CSD at the N-terminus and a Gly-Arg-rich C-terminal region, which together confer RNA-binding activity (59). Since structure predictions of the RBP-16 C-terminal domain again indicates the absence of α-helical or β-strand regions, we believe that this domain is also likely to adopt an extended structure similar to those shown in Figure 8B.

We can thus define a special class of auxiliary domains able to assist CSD and RRM in their dual RNA-binding function. On the one hand they can unstack RNA bases and thus make key RNA regions available for the first step of specific recognition by CSD or RRM. On the other hand they can modulate the relatively non-specific RNA packaging induced by the selective domains.

Interestingly, it has been reported that a number of RNA-binding proteins from a cyanobacterium comprise a single RRM module and are highly expressed in response to cold-shock (60). Even more intriguing is the fact that these proteins also contain a short C-terminal Gly-rich domain. This correlation between the presence of an RRM and the response to low ambient temperatures has also been observed in plant and mammalian Gly-rich RNA-binding proteins, such as the mouse cold-inducible RNA-binding protein, CIRP (61). The N-terminal RRM of CIRP is associated with an Arg-Gly-rich C-terminal domain whose structure can again be predicted to adopt an extended conformation. It has been suggested that the cold-shock response depends on RNA-binding activities (62) and the very recent discovery that the cold stress-induced cyanobacterial DEAD-box protein CrhC is an RNA helicase is consistent with such a hypothesis (63). In particular the increased stability of mRNA at sub-optimal temperatures would be counteracted by the capacity of key RNA-binding proteins to promote/stabilise single-stranded RNA. Our results show that CSD- and RRM-containing proteins possess this capacity, especially if they function in conjunction with a particular auxiliary domain, rich in both arginine and aromatic residues and organised in an extended PPII helix-like structure.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to David Barker for useful suggestions and careful reading of the manuscript. This work was granted in part by the Région Midi-Pyrénées and, in part, by grants from the Fondation de la Recherche Médicale (FRM no. 20000061-12) and the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC no. 7373).

References

- 1.Weighardt F., Biamonti,G. and Riva,S. (1996) The roles of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNP) in RNA metabolism. Bioessays, 18, 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burd C.G. and Dreyfuss,G. (1994) Conserved structures and diversity of functions of RNA-binding proteins. Science, 265, 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagai K., Oubridge,C., Jessen,T.H., Li,J. and Evans,P.R. (1990) RNA–protein complexes. Nature, 348, 515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman D.W., Query,C.C., Golden,B.L., White,S.W. and Keene,J.D. (1991) RNA-binding domain of the A protein component of the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein analyzed by NMR spectroscopy is structurally similar to ribosomal proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 2495–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oubridge C., Ito,N., Evans,P.R., Teo,C.H. and Nagai,K. (1994) Crystal structure at 1.92 Å resolution of the RNA-binding domain of the U1A spliceosomal protein complexed with an RNA hairpin. Nature, 372, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deo R.C., Bonanno,J.B., Sonenberg,N. and Burley,S.K. (1999) Recognition of polyadenylate RNA by the poly(A)-binding protein. Cell, 98, 835–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding J., Hayashi,M.K., Zhang,Y., Manche,L., Krainer,A.R. and Xu,R.M. (1999) Crystal structure of the two-RRM domain of hnRNP A1 (UP1) complexed with single-stranded telomeric DNA. Genes Dev., 13, 1102–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Handa N., Nureki,O., Kurimoto,K., Kim,I., Sakamoto,H., Shimura,Y., Muto,Y. and Yokoyama,S. (1999) Structural basis for recognition of the tra mRNA precursor by the sex-lethal protein. Nature, 398, 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graumann P. and Marahiel,M.A. (1996) A case of convergent evolution of nucleic acid binding modules. Bioessays, 18, 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sommerville J. and Ladomery,M. (1996) Masking of mRNA by Y-box proteins. FASEB J., 10, 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landsman D. (1992) RNP-1, an RNA-binding motif is conserved in the DNA-binding cold shock domain. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 2861–2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schindelin H., Marahiel,M.A. and Heinemann,U. (1993) Universal nucleic acid-binding domain revealed by crystal structure of the B. subtilis major cold-shock protein. Nature, 364, 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnuchel A., Wiltscheck,R., Czisch,M., Herrler,M., Willimsky,G., Graumann,P., Marahiel,M.A. and Holak,T.A. (1993) Structure in solution of the major cold-shock protein from Bacillus subtilis. Nature, 364, 169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schindelin H., Jiang,W., Inouye,M. and Heinemann,U. (1994) Crystal structure of CspA, the major cold shock protein of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5119–5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newkirk K., Feng,W., Jiang,W., Tejero,R., Emerson,S.D., Inouye,M. and Montelione,G.T. (1994) Solution NMR structure of the major cold shock protein (CspA) from Escherichia coli: identification of a binding epitope for DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 5114–5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroder K., Graumann,P., Schnuchel,A., Holak,T.A. and Marahiel,M.A. (1995) Mutational analysis of the putative nucleic acid-binding surface of the cold-shock domain, CspB, revealed an essential role of aromatic and basic residues in binding of single-stranded DNA containing the Y-box motif. Mol. Microbiol., 16, 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginisty H., Sicard,H., Roger,B. and Bouvet,P. (1999) Structure and functions of nucleolin. J. Cell Sci., 112, 761–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolffe A.P. (1994) Structural and functional properties of the evolutionarily ancient Y- box family of nucleic acid binding proteins. Bioessays, 16, 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouvet P., Matsumoto,K. and Wolffe,A.P. (1995) Specific regulation of Xenopus chromosomal 5S rRNA gene transcription in vivo by histone H1. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 28297–28303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lapeyre B., Bourbon,H. and Amalric,F. (1987) Nucleolin, the major nucleolar protein of growing eukaryotic cells: an unusual protein structure revealed by the nucleotide sequence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 1472–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tafuri S.R. and Wolffe,A.P. (1990) Xenopus Y-box transcription factors: molecular cloning, functional analysis and developmental regulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 9028–9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serin G., Joseph,G., Ghisolfi,L., Bauzan,M., Erard,M., Amalric,F. and Bouvet,P. (1997) Two RNA-binding domains determine the RNA-binding specificity of nucleolin. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 13109–13116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai D.E., Harper,D.S. and Keene,J.D. (1991) U1-snRNP-A protein selects a ten nucleotide consensus sequence from a degenerate RNA pool presented in various structural contexts. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 4931–4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greer J. (1991) Comparative modeling of homologous proteins. Methods Enzymol., 202, 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laskowski R.A., Moss,D.S. and Thornton,J.M. (1993) Main-chain bond lengths and bond angles in protein structures. J. Mol. Biol., 231, 1049–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris A.L., MacArthur,M.W., Hutchinson,E.G. and Thornton,J.M. (1992) Stereochemical quality of protein structure coordinates. Proteins, 12, 345–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wesson L. and Eisenberg,D. (1992) ) Atomic solvation parameters applied to molecular dynamics of proteins in solution. Protein Sci., 1, 227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathews D.H., Sabina,J., Zuker,M. and Turner,D.H. (1999) Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol., 288, 911–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Z. and Scheraga,H.A. (1987) Monte Carlo-minimization approach to the multiple-minima problem in protein folding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 6611–6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazaridis T. and Karplus,M. (2000) Effective energy functions for protein structure prediction. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 10, 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erard M.S., Belenguer,P., Caizergues-Ferrer,M., Pantaloni,A. and Amalric,F. (1988) A major nucleolar protein, nucleolin, induces chromatin decondensation by binding to histone H1. Eur. J. Biochem., 175, 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kharrat A., Derancourt,J., Doree,M., Amalric,F. and Erard,M. (1991) Synergistic effect of histone H1 and nucleolin on chromatin condensation in mitosis: role of a phosphorylated heteromer. Biochemistry, 30, 10329–10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghisolfi L., Joseph,G., Amalric,F. and Erard,M. (1992) The glycine-rich domain of nucleolin has an unusual supersecondary structure responsible for its RNA-helix-destabilizing properties. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 2955–2959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghisolfi L., Kharrat,A., Joseph,G., Amalric,F. and Erard,M. (1992) Concerted activities of the RNA recognition and the glycine-rich C-terminal domains of nucleolin are required for efficient complex formation with pre-ribosomal RNA. Eur. J. Biochem., 209, 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serin G., Joseph,G., Faucher,C., Ghisolfi,L., Bouche,G., Amalric,F. and Bouvet,P. (1996) Localization of nucleolin binding sites on human and mouse pre-ribosomal RNA. Biochimie, 78,530–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghisolfi-Nieto L., Joseph,G., Puvion-Dutilleul,F., Amalric,F. and Bouvet,P. (1996) Nucleolin is a sequence-specific RNA-binding protein: characterization of targets on pre-ribosomal RNA. J. Mol. Biol., 260, 34–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ginisty H., Serin,G., Ghisolfi-Nieto,L., Roger,B., Libante,V., Amalric,F. and Bouvet,P. (2000) Interaction of nucleolin with an evolutionarily conserved pre-ribosomal RNA sequence is required for the assembly of the primary processing complex. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 18845–18850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouvet P., Jain,C., Belasco,J.G., Amalric,F. and Erard,M. (1997) RNA recognition by the joint action of two nucleolin RNA-binding domains: genetic analysis and structural modeling. EMBO J., 16, 5235–5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allain F.H., Bouvet,P., Dieckmann,T. and Feigon,J. (2000) Molecular basis of sequence-specific recognition of pre-ribosomal RNA by nucleolin. EMBO J., 19, 6870–6881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginisty H., Amalric,F. and Bouvet,P. (2001) Two different combinations of RNA-binding domains determine the RNA-binding specificity of nucleolin. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 14338–14343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phadtare S. and Inouye,M. (1999) Sequence-selective interactions with RNA by CspB, CspC and CspE, members of the CspA family of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol., 33, 1004–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manavalan P. and Johnson,W.C. (1983) Sensitivity of circular dichroism to protein tertiary structure class. Nature, 305, 831–832. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McPhie P. and Shrager,R.I. (1992) An investigation of the thermal unfolding of swine pepsinogen using circular dichroism. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 293, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allain F.H., Gilbert,D.E., Bouvet,P. and Feigon,J. (2000) Solution structure of the two N-terminal RNA-binding domains of nucleolin and NMR study of the interaction with its RNA target. J. Mol. Biol., 303, 227–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conte M.R., Grune,T., Ghuman,J., Kelly,G., Ladas,A., Matthews,S. and Curry,S. (2000) Structure of tandem RNA recognition motifs from polypyrimidine tract binding protein reveals novel features of the RRM fold. EMBO J., 19, 3132–3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Philippe C., Benard,L., Portier,C., Westhof,E., Ehresmann,B. and Ehresmann,C. (1995) Molecular dissection of the pseudoknot governing the translational regulation of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein S15. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woody R.W. (1995) Circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol., 246, 34–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouvet P., Dimitrov,S. and Wolffe,A.P. (1994) Specific regulation of Xenopus chromosomal 5S rRNA gene transcription in vivo by histone H1. Genes Dev., 8, 1147–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Girard J.P., Lehtonen,H., Caizergues-Ferrer,M., Amalric,F., Tollervey,D. and Lapeyre,B. (1992) GAR1 is an essential small nucleolar RNP protein required for pre-rRNA processing in yeast. EMBO J., 11, 673–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murray M.T. (1994) Nucleic acid-binding properties of the Xenopus oocyte Y box protein mRNP3+4. Biochemistry, 33, 13910–13917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rost B., Sander,C. and Schneider,R. (1994) PHD—an automatic mail server for protein secondary structure prediction. Comput. Appl. Biosci., 10, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sreerama N. and Woody,R.W. (1994) Poly(pro)II helices in globular proteins: identification and circular dichroic analysis [published erratum appears in Biochemistry (1995), 34, 7288]. Biochemistry, 33, 10022–10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsumoto K., Meric,F. and Wolffe,A.P. (1996) Translational repression dependent on the interaction of the Xenopus Y- box protein FRGY2 with mRNA. Role of the cold shock domain, tail domain, and selective RNA sequence recognition. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 22706–22712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yurkova M.S. and Murray,M.T. (1997) A translation regulatory particle containing the Xenopus oocyte Y box protein mRNP3+4. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 10870–10876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biamonti G. and Riva,S. (1994) New insights into the auxiliary domains of eukaryotic RNA binding proteins. FEBS Lett., 340, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sommerville J. (1999) Activities of cold-shock domain proteins in translation control. Bioessays, 21, 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salvetti A., Batistoni,R., Deri,P., Rossi,L. and Sommerville,J. (1998) Expression of DjY1, a protein containing a cold shock domain and RG repeat motifs, is targeted to sites of regeneration in planarians. Dev. Biol., 201, 217–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayman M.L. and Read,L.K. (1999) Trypanosoma brucei RBP16 is a mitochondrial Y-box family protein with guide RNA binding activity. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 12067–12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pelletier M., Miller,M.M. and Read,L.K. (2000) RNA-binding properties of the mitochondrial Y-box protein RBP16. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1266–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maruyama K., Sato,N. and Ohta,N. (1999) Conservation of structure and cold-regulation of RNA-binding proteins in cyanobacteria: probable convergent evolution with eukaryotic glycine-rich RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2029–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nishiyama H., Itoh,K., Kaneko,Y., Kishishita,M., Yoshida,O. and Fujita,J. (1997) A glycine-rich RNA-binding protein mediating cold-inducible suppression of mammalian cell growth. J. Cell. Biol., 137, 899–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Phadtare S., Alsina,J. and Inouye,M. (1999) Cold-shock response and cold-shock proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol., 2, 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu E. and Owttrim,G.W. (2000) Characterization of the cold stress-induced cyanobacterial DEAD-box protein CrhC as an RNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 3926–3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]