Abstract

BACKGROUND

Research has identified barriers and facilitators affecting cancer survivors’ return to work (RTW) following the end of active treatment (surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy). However, few studies have focused on barriers and facilitators that cancer survivors experience while working during active treatment. Strategies used by cancer survivors to solve work-related problems during active treatment are underexplored.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to describe factors that impact, either positively or negatively, breast cancer survivors’ work activities during active treatment.

METHODS

Semi-structured, recorded interviews were conducted with 35 breast cancer survivors who worked during active treatment. Transcripts of interviews were analyzed using inductive content analysis to identify themes regarding work-related barriers, facilitators and strategies.

RESULTS

Barriers identified included symptoms, emotional distress, appearance change, time constraints, work characteristics, unsupportive supervisors and coworkers, family issues and other illness. Facilitators included positive aspects of work, support outside of work, and coworker and supervisor support. Strategies included activities to improve health-related issues and changes to working conditions and tasks.

CONCLUSIONS

Breast cancer survivors encounter various barriers during active treatment. Several facilitators and strategies can help survivors maintain productive work activities.

Keywords: Content analysis, technology and tools, accommodation, cancer survivor, working during active treatment

1. Introduction

An estimated 6.7 million working-age Americans have a cancer diagnosis [1]. Work remains important for cancer survivors [2]. The National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship defines a cancer survivor as “anyone who has been diagnosed with cancer, from the time of diagnosis through the balance of his or her life”. Some cancer survivors must work for economic or health insurance reasons. For others, work may help retain a sense of normalcy and relieve boredom and isolation [3, 4]. Work can also be a distraction from cancer and cancer treatments [4–6].

The duration of active treatment varies by individual and cancer diagnosis, and may be as little as the time required for a single surgery, or multiple months of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation. Cancer diagnosis and active treatment (i.e. period of time during which curative-intent surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation are delivered) can profoundly affect work ability. Previous research has demonstrated favorable return to work (RTW) rates of cancer survivors after active treatment. Approximately 80% of breast cancer survivors were able to continue to work after they have completed all cancer treatments [7, 8], but fewer cancer survivors worked during active treatment [2, 9, 10]. During active treatment, survivors reported poorer health conditions, lower ability to work, and decreased work productivity as compared to a non-cancer population [11–15]. Cancer survivors often require time off from work for medical appointments during active treatment, and experience significant symptoms such as fatigue and pain [16] as well as emotional distress [17]. Cancer survivors also reported feeling vulnerable about their survival in the future, and uncertain about work resumption during active treatment [18]. Despite health insurance coverage, 38% of cancer survivors during treatment experienced financial hardship, especially younger survivors [19]. Being able to work during active treatment may mitigate this financial burden.

Few studies have specifically focused on work during active treatment. Most studies on RTW retrospectively examined the effect of active treatment using questionnaires one year or more after diagnosis [5]. For example, Bouknight et al. interviewed cancer survivors 12 and 18 months after cancer diagnosis but focused on the effect of chemotherapy [20]. Short et al. interviewed cancer survivors who were 1 to 5 years post cancer diagnosis, and asked about their employment since time of diagnosis to follow-up [9]. However, such retrospective evaluations of work experience may suffer from selection and recall bias, especially for long-term cancer survivors [21]. The dynamic nature of changes in job made retrospective evaluation more complicated as some job changes may not be related to cancer [21]. In addition, many studies have only looked at survivors who returned to work at variable time periods post active treatment, or did not differentiate between those survivors continuing to work and those returning to work post-treatment. Those studies focused on the changes (e.g. change of meaning of work, change of ability to work, change of confidence) due to cancer on work and life of cancer survivors, but failed to explicitly examine work experiences during active treatment [4, 22].

Previous studies investigating cancer survivors and RTW have found that symptoms, non-supportive work environment, employer discrimination, and manual work were barriers to RTW [8, 23] while employer accommodation, flexibility, coworker support, and supervisor support [5, 7, 24] were found to be important facilitators. Although some research has been done on facilitators and barriers of cancer survivors’ RTW, little is known on whether cancer survivors who worked during active treatment encounter the same barriers and facilitators. In addition, previous studies have primarily focused on cancer survivors’ coping strategies, such as acceptance, religion, and distraction from cancer [25–28]. Work-related strategies developed by cancer survivors to solve work-related problems are under-explored. Therefore, a prospective, qualitative study was conducted to examine the impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment on breast cancer survivors’ RTW and ability to work. The aim was to describe the barriers, facilitators and strategies of breast cancer survivors who worked during active treatment, and to understand the importance and the availability of support during active treatment.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting and participants

This study was part of a larger study to improve the ability to work of breast cancer survivors (the WISE study, clinical trial number: NCT01799031). Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Participants were recruited from The University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC). Inclusion criterion as follows; 1) newly diagnosed female breast cancer patients 2) aged 25–65 years old, 3) without prior cancer diagnosis, 4) employed at time of cancer diagnosis (defined as working > 20 hrs/week), 5) on active treatment (surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiation) but 6) within 6 months of completing active treatment were eligible. Exclusion criterion as follows; 1) patients who developed progressive disease during treatment, 2) patients not intending to resume to work after active treatment or 3) patients with distant metastases.

Working status at baseline and 3 months post accrual was derived from responses to two survey questions: 1) current work status being full or part time and 2) work hours during past two weeks being great than zero. Participants who worked at baseline during active treatment and those who did not work at baseline, but worked at a 3-month time point while still on treatment were included in this study. Therefore, participants included breast cancer survivors who worked throughout treatment or those who took time off but returned to work during part of active treatment.

2.2. Data collection

Both semi-structured interviews and questionnaires were employed to collect data. Electronic questionnaires on socio-demographic information and work-related questions were administered at enrollment (baseline) and 3, 6 and 12 months after baseline assessment. Participants completed the questionnaire either in the oncology clinic using a tablet or via an email link. Data from the baseline questionnaires used in this study included sociodemographic information (e.g., age, race, occupation, household incomes, and highest level of education) and work status (e.g. work full time/part time or not work, and work hours per week in the past two weeks). Semi-structured, 30-minute face-to-face interviews on barriers, facilitators and strategies affecting work were conducted at 3 months and 6 months post-baseline in a private meeting room in the oncology clinic, and were audio-recorded. When face-to-face interviews were not feasible, a telephone interview was conducted for two participants. Two study coordinators from UWCCC received training from the research team on conducting interviews with patients, and led the interview using the interview guide, which included the following questions reported on in this paper.

Tell me about your decision to go to work.

Did cancer diagnosis or treatment affect your work? What difficulties do you have at work?

What helped you be able to work? Who has provided support for you to work?

Did you get as much support as you wanted or needed?

Can you tell me what strategies you used to keep working during active treatment?

Are there other things that affected you being able to work during active treatment?

The study coordinators were observed by researchers to ensure interviews were conducted in a similar manner. Two research graduate students participated in the interviews to take notes, record the interview, and ask follow up questions. Recorded audio files from the interviews were transcribed, reviewed for accuracy, and any sensitive information was redacted. The present analysis used data from the 3-month interview since participants were still on active treatment or just completing active treatment at the 3-month time point (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of Socio-demographic information

| Variables | (N = 35) N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 48.06 (10.3) | |

| Race | White | 33 (94.3) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.9) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.9) | |

| Education | Graduate or professional degree | 9 (25.7) |

| Some graduate school | 1 (2.9) | |

| Four year college graduate | 12 (34.3) | |

| Two year college graduate | 3 (8.6) | |

| Some college | 2 (5.7) | |

| Technical or trade school | 2 (5.7) | |

| High school graduate/GED | 6 (17.1) | |

| Income | <$15,000 | 1 (2.9) |

| $15,001–$30,000 | 1 (2.9) | |

| $30,001–$50,000 | 4 (11.4) | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 4 (11.4) | |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 8 (22.9) | |

| $100,001–$150,000 | 11 (31.4) | |

| $150,001–$200,000 | 1 (2.9) | |

| More than $200,000 | 3 (8.6) | |

| I prefer not to answer | 2 (5.7) | |

| Occupation | Professional | 20 (57.1) |

| Management/administration | 5 (14.3) | |

| Technical | 1 (2.9) | |

| Service | 1 (2.9) | |

| Clerical | 4 (11.4) | |

| Other | 4 (11.4) | |

| If on treatment at 3 month time point | On treatment | 17 (48.57) |

| Off treatment | 18 (51.43) |

2.3. Data analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using inductive content analysis to identify work-related barriers, facilitators, and strategies. All transcripts were imported into NVivo10 (QSR, Australia), a qualitative data analysis software. Transcripts from the first five 3-month interviews were coded by the research team (multidisciplinary experts from human factors engineering, physical therapy, oncology and nursing) and used to identify themes on barriers, facilitators and strategies. This provided the initial coding scheme, which included the themes and their definitions. Two researchers then coded the subsequent interview transcripts independently, based on the initial coding scheme, and compared their results. Any disagreements or newly emerging themes were first discussed by the two original coders. New themes and any unresolved disagreements were then brought to the entire research team for consensus.

2.4. Definitions

Barriers were defined as any factors (people, places or things) that breast cancer survivors perceived as encumbering their work: e.g. heavy physical demanding tasks or unsupportive supervisors. Facilitators were defined as any factors that breast cancer survivors perceived as being helpful to their work: e.g. flexible working hours or supportive coworkers. An important feature of facilitators and barriers is that they are aspects of the system, i.e. the properties of the organization or work place. Strategies were defined as any factors or actions that a survivor utilized or implemented to assist in her ability to continue to work. Strategies could involve the utilization of facilitators to overcome barriers: e.g. a survivor requesting a lift table to help lift heavy objects.

3. Results

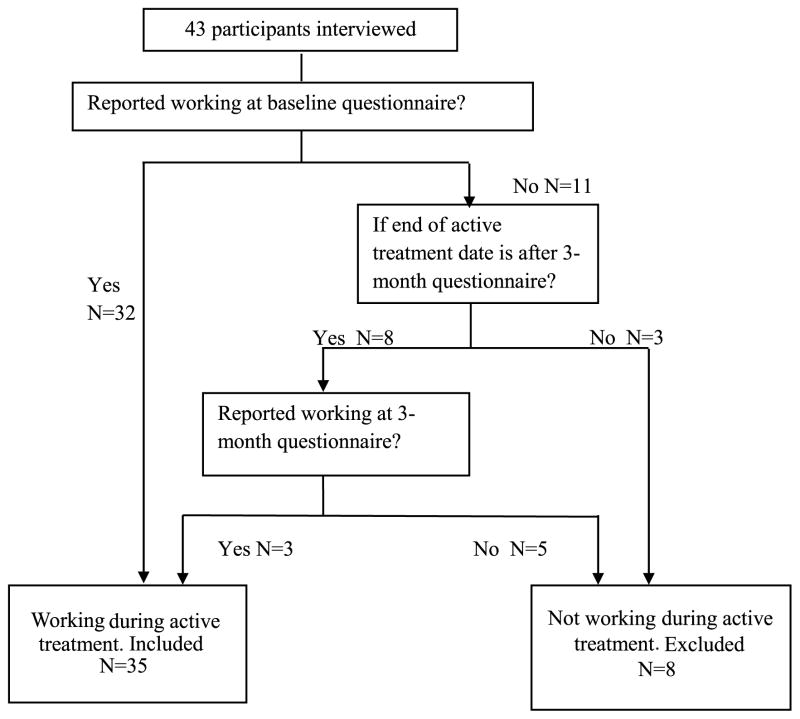

Forty-four participants were enrolled in the WISE parent study. One participant was excluded from follow-up assessment due to development of metastatic disease after baseline assessment. Thus, 43 participants were interviewed. Among them, 35 participants worked during active treatment, which was based on their work hours and work status reported at baseline, 3 month questionnaire, and treatment end date (Fig. 1). These 35 participants constitute the cohort for this analysis. Table 1 provides the socio-demographic information of participants. The majority were Caucasian (94.3%) and had at least a college education (77.2%). Breast cancer survivors reported varying work patterns during active treatment: some worked through active treatment and only took time off for medical appointments; some worked during radiotherapy but took time off during chemotherapy; some worked during chemotherapy and radiotherapy but took time off for surgery.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of participants selection process.

3.1. Barriers

Barriers identified during interviews (Table 2) included: symptoms, emotional distress, appearance change, time constraints, work characteristics, unsupportive supervisors or coworkers, family issues and other illness. Each of these barriers with supporting data are described below. Although all the participants discussed barriers, six participants perceived that their cancer diagnosis or treatment did not affect their work overall.

Table 2.

Barriers identified

| Theme and definition | Example |

|---|---|

| Symptoms – due to cancer treatment or medication that negatively affect the ability to work of breast cancer survivors. |

|

| Emotional distress – The reaction due to cancer diagnosis or treatment that negatively affected breast cancer survivors’ ability to work. | |

| Unwanted appearance change – The appearance change due to cancer treatment that negatively affected breast cancer survivors’ ability to work. |

|

| Time constraints – The time needed to attend cancer treatments/appointment negatively affected breast cancer survivors’ ability to work. |

|

| Job/Work characteristics – Requirements or inherent nature of the job that made working difficult. |

|

| Unsupportive supervisors and coworkers – Supervisor or coworkers lack of support affected breast cancer survivors’ ability to work. |

|

| Other illness and family issues – Other events that were not caused by cancer that affected breast cancer survivors’ ability to work. |

|

3.1.1. Symptoms

Participants discussed various symptoms due to cancer treatment that contributed to difficulties working during active treatment. They reported blurry vision, cognitive impairment, fatigue, lack of mobility, lack of strength, nausea, neuropathy, pain, fever, shortness of breath, and sleepiness. Symptoms resulted in difficulties performing work tasks, or working the required number of hours. “It was definitely all the symptoms and just, you know, the rigor of having to be here [at work] so much. But I think the symptoms …, more so than anything, it was how you felt. Fatigue is the absolute worst.”

3.1.2. Emotional distress

Emotional distress due to cancer diagnosis also impacted work during active treatment. For example: “So initially, the processing of, oh gosh, I’m 40 years old, and I have two little kids, and I was just diagnosed with breast cancer. So I, for a couple days didn’t work just because I was in shock and processing.”

3.1.3. Appearance change

Unwanted changes to appearance, such as losing hair and nail changes made breast cancer survivors uncomfortable interacting with people at work. They worried about others’ negative impression of them due to the appearance change. For example: “You don’t expect those things, but people notice those things in my profession. I’m shaking hands with people on a regular basis, and you don’t think that having a, it looks like a dirty thumbnail doesn’t make an impression on somebody when you’re interviewing them.”

3.1.4. Time constraints

Time constraints included the time needed to attend cancer treatments/appointment. Participants discussed the work schedule disruption and inability to attend work due to cancer treatment and medical appointment. For example: “I kept a full-time status. But obviously, that was difficult, because I had surgery and chemotherapy. So I obviously missed days that I had to miss. And then there were several days that I missed because I was so sick.” “So it [treatment] disrupts my schedule for work because I have to travel.”

3.1.5. Job/work characteristics

Job/work characteristic barriers included physical demanding tasks, job stress, job challenges (e.g. traveling and driving), hazards associated with work tasks, lack of flexibility, inaccessibility of technology, unable to use technology/tools at work, and difficulty communicating about cancer at work.

Participants reported difficulties performing physically demanding tasks. They were also concerned about physically demanding tasks negatively affecting their health. For example: “It did in the sense that I wasn’t able to do some of the things like climb on a roof to take readings for stack runners, those types of things. Collect storm water things, you know, for outside. Because I would be out in the elements, and the only way you can do storm water assessments is to be out in the rain, which wasn’t good for me.”

Job stress was recognized as a barrier to work by some participants. The addition of the stress of a cancer diagnosis and treatment to an already stressful job was described by one participant, “Yeah, I mean, there’s only, you know, six people, seven, that work there, and so it was stressful, very stressful. And not only that, the calls in between the diagnosis before the cancer, needing to take phone calls from here, the cancer center, and you know, you have your phone on you at all times, and you’re with a patient, and you have to step out of the room to take a phone call.”

Participants discussed how hazards associated with tasks, such as working with kids or older adults, negatively influenced their work during active treatment because of health-related concerns. For example, a participant reported the reason that she stopped working during chemotherapy was that she worked with kids: “I ended up stopping work because, first of all, kids are sick. They have lots of germs … And they cough right at you.”

Inflexibility at the work place was also a barrier recognized by participants since they needed time off for treatments and recovery. For instance, jobs that required set working schedules at set locations, or jobs that did not allowing breaks were problematic. Being unable to work remotely was reported frequently as a significant barrier. Participants also mentioned that the inability to work at home was often due to lack of technology or resources being supplied by the job. Commuting to work was a challenge: “ … the one thing that I wish they would’ve done is let me work from home more. Because they’re just saving that 45 minutes of getting here and going home every day. Because there were a lot of days when I drove home, that I was struggling, don’t let me fall asleep, God. Don’t let me hit another car because I am that tired, you know.” “Because I deal with a lot of confidential websites, okay, and that’s not something that they’re willing to just set up for everybody in a home environment.”

Inability to use technology was identified as another barrier. A participant revealed how limited mobility after surgery made it hard to use a computer mouse, and blurry vision due to chemotherapy made it difficult to read the computer screen. For example: “ … as I said, my hardest part is just moving the mouse. After surgery, it was just a little more tender to do that.”

Some participants reported experiencing difficulty sharing information about their cancer diagnosis with others at work. They were concerned that a cancer diagnosis might negatively impact the opinions of people at work. “I’m like… do I tell them it’s a wig? Do I not tell them? Like that sort of thing, but the reason why I didn’t want them to be, to know about that out in the units was I didn’t really want the patients [she worked with patients] to know. And sometimes, you know how it is. Sometimes people talk in the nurses’ station and are overheard by patients. And I didn’t want to get a lot of questions or people to know.”

3.1.6. Unsupportive supervisors and coworkers

Participants reported unsupportive supervisors and coworkers as barriers to working during active treatment. Issues included: 1) not enough accommodations and support being provided, 2) accommodations that were offered but not implemented, and 3) over-protectiveness at work. Participants reported that some employers did not provide accommodations at all or did not provide enough accommodations. They also were unwilling to reduce working hours when requested. “And they, just so you know, were extremely unwilling to work with my hours. So I was required to be onsite for them 24 hours in the week, plus I was running my own business.”

A participant mentioned her work schedule was filled even before she took time off: “ … actually even before I left, the [work] schedule was already filled. But I have to take care of myself, and that’s the part that’s very stressful too.” Some supervisors or employers offered accommodations, but did not implement them. A participant talked about her company planning to offer accommodations at the beginning of the cancer treatment, but never receiving any: “We talked about it at the beginning after surgery, when we knew I would have to have chemo for four months, they discussed re-working kind of my duties to lighten my load. And then that kind of petered out after, I think, a couple weeks.” The participant also mentioned that she was allowed to work at home, but an unsupportive supervisor questioned the amount of work she was doing at home: “I was kind of questioned by my supervisor about how much work I was really doing from home. So that kind of made me not ever want to work from home anymore, and I really didn’t.”

However, too much support by supervisors and coworkers was also identified as a barrier. Coworkers and supervisors sometimes removed work activities or did not offer work activities that participants felt they were capable of performing. “And they would purposely not be putting me on the next big project. So that’s where, you know … It wasn’t considered in their eyes a bad thing to take the duties away from me if they’re trying to help. You know, but in my mind, it’s like, don’t take those away from me. You know, so.”

Participants also discussed other difficulties which included indifferent supervisors, a lack of part-time opportunities, and lack of benefits (e.g. vacation or sick days) due to having a new job.

3.1.7. Other illness and family issues

Other illnesses or conditions affecting the cancer survivor, or her family, had an impact on the ability to work for some participants. Family issues included moving, an ill family member, and a family member being laid off. “I got sick with the normal flu, and it lasted for four-and-a-half weeks. You know, and, I mean, the whole [work] department were just, everybody’s sick. You know, so maybe if I didn’t have cancer, I still would’ve gotten sick.” “Yeah, my husband being laid off was the big one. We had a lot of drama, I guess, surrounding my cancer diagnosis. That probably made it just more stressful to work.”

3.2. Facilitators

Participants reported both facilitators within, and outside of the workplace, that assisted with working during active treatment. Table 3 presents all the facilitators, which include positive aspects of work, support outside the workplace, and coworker and supervisor support.

Table 3.

Facilitators identified

| Theme and definition | Example |

|---|---|

| Positive aspects of work – The reasons why breast cancer survivors continue working during active treatment. |

|

| Support from outside the workplace – Non-work support mainly helped with breast cancer survivors’ emotional health and life, which benefited their ability to work indirectly. |

|

| Coworker and supervisor support at work – Supervisors or coworkers offered accommodations for breast cancer survivors. |

|

3.2.1. Positive aspects of work

Positive aspects of work included income/finances, job retention, love of the job, sense of normalcy, sense of responsibility, and social aspects. Any single participant might report multiple positives inherent to their work. For example: “I think it was going to keep my mind off of things, well, also monetary factor, but mostly, I think, to keep my mind off, like kind of busy.” “Plain and simple, I love my job.”

3.2.2. Support outside the workplace

Overall, support outside the workplace mainly helped with participants’ emotional health, which in turn benefited their ability to work. Support outside the workplace included: family and friends support, having a positive outlook, and other support such as support from health care providers, social workers, and cancer survivors program.

Support from family and friends was recognized by all of the participants as an important facilitator as this assisted both financially and emotionally. “My husband and my mother made it possible. My mom lives with us now, and is amazing in helping keep the house going so I can focus the energy I had on my kids and then on some of the work too, so.”

Having a positive outlook was reported by several participants as a facilitator “As long as my attitude is good, I feel good, people around me feel good, and that’s, I mean, not to get too philosophical on anyone, but I just think that attitude is everything. And if you sit and wallow in your grief, you’re probably not going to heal very well. And I just get up and pretend like nothing’s wrong, and I don’t let anything slow me down.”

Support from health care providers, social workers, and cancer survivor advocacy groups was also reported by some participants as a positive facilitator. For example: “I had come in for radiation, and I talked to a nurse here. I had asked to see a nurse because I was feeling so poorly. And she really gave me support. She’s the one who said like you really need to take care of yourself and rest as much as you can. And it was really what I needed to hear. And really, you know, because it’s hard for us to call people up and say, no, I can’t do this, and, no, I can’t do that.”

3.2.3. Coworker and supervisor support at work

Even though some breast cancer survivors did not request accommodations, some supervisors and employers offered accommodations. These included reducing workload or/and work hours for participants, changing work tasks, offering different ways of doing tasks, and offering benefits such as paid time off and FMLA (Family and Medical Leave Act). Some employers provided paid time off, and protected their job position when breast cancer survivors took needed time off. For example: “..and as much time as I spent away from work, they did not take one dime out of my salary. I even got a bonus, which was unexpected.”

Related to paid leave was the use of flexible work hours and work location. It allowed participants to take time off for medical appointments and make up the work hours later. For example: “So I’ve been able to go to chemo and doctor’s appointments and CT scans. I’m planning a scan this morning. I was gone for an hour and a half.”

Most participants talked about experiencing decreased work ability due to symptoms. Reducing workload and shortening work hours, altering work tasks (typically from physically demanding tasks to sedentary tasks), and offering different ways of doing tasks to lower work demands were reported as accommodations that improved ability to work. For example: “I was given that discretion that if I couldn’t go out to their home, I could try to do as much as I could over the phone.” “Because she said she would … modify whatever I needed to do.”

Coworkers helped in multiple ways. They were able to take over some work tasks, helped with participants’ performing tasks, and switched work tasks with participants when they were not feeling well. For example: “the girl in the front that answers the phone, a couple times she would come back. If I was too tired, I would just go answer phones. So I had that out if I needed it.” “So I didn’t have any difficulty, and people were more than accommodating and would say, if you can’t work tonight, I’ll find somebody to work.”

Coworkers and supervisors also provided emotional support. For example: “Work has been very supportive. Like I said, they want me to get better, and they want me to get back to work. Yeah, it’s nice. But I feel they genuinely care about me. It’s not like now there’s this big hole, this big void. I feel they genuinely care about me. So on the work side, I have that support, which is really nice.”

3.3. Strategies

In order to overcome barriers, survivors also developed strategies to assist with continuing to work (Table 4). Two types of strategies were identified: health-related strategies to assist work indirectly, and work-related strategies that directly focused on work barriers.

Table 4.

Strategies identified

| Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Health-related strategies – Health-related strategies of breast cancer survivors mainly focused on improving overall health, which improves the ability to work. |

|

| Work-related strategies – Work-related strategies focused on improving the way breast cancer survivors’ performance work task. |

|

3.3.1. Health-related strategies

Health-related strategies mainly focused on improving health in an effort to improve ability to work. Many breast cancer survivors viewed exercise as a main strategy they employed to facilitate their ability to work. Participants also reported eating a healthy diet, minimizing exposure to germs, and reading books and online information to learn more about cancer. For example: “You know, the only thing I was able to do then was to take the weights to keep my upper body moving and I also do exercises. I lay on the floor and stretch my back to keep my back flexible because you have a lot of bending, stooping, and stuff that you’ve got to do.”

3.3.2. Work-related strategies

Work-related strategies focused on improving the way participants performed work tasks. Because many participants reported some cognitive impairments or memory problems, they used strategies such as taking notes, keeping good organizational skills, devising plans, making lists, and prioritizing tasks while working. Some participants adjusted their work schedule, work tasks, and workload based on the timing of their cancer treatments as the treatments had the ability to impact their health. They worked when they felt they were able to. Reducing non-work related activities was also a strategy used by several participants, such as hiring housekeepers and not attending social events, so they could focus on work and their health. Some examples include: “I plowed through it, but I made a lot of lists, because I was definitely having trouble remembering things, which I think was caused by the drugs I was on, I think, when it was all those side effects.” “So as the chemo was going along, I couldn’t do that totally. I tended to work more eight hour days. And I would frontload some hours on the weekend, like put in about eight hours when nobody is there to do paperwork so in case I felt bad during the week.” “and what got me through that last week was just saying no to everything else except working and resting.”

Another significant strategy identified was to adjust the ways of doing tasks, especially for those with physically demanding tasks. For example: “An example would be I have to deep suction through his trach sometimes, and usually in between the deep suction, and then use the ambu bag to re-ventilate, and I physically couldn’t do that. But we worked around it. . . . . And so we’ve made adjustments.”

Using or adjusting the tools to assist with work was another significant strategy recognized by participants. “I learned how to use different tools differently, I can put it to you that way. It’s like I have a little grabber for picking up stuff off the floor so I don’t have to bend over to do it. It sits right on my cart.” Participants also described enlarging font size to help with visualization.

Some participants used technology to assist with working during active treatment. Computers and smart phones allowed breast cancer survivors to work remotely, at home or even during treatments at the hospital or clinic. For example: “The other thing is technology now, you know, my tablet, my phone, my, you know, I could do it from bed. I didn’t even have to get out of bed to keep my fingers on the pulse of what was happening. So that’s changed so much in the last five years.”

Making the work environment comfortable was also mentioned by some participants. A comfortable environment made participants relax more and feel better during work. “We like brought in a teapot and had teatime and had a little tea bar in the office, so there were some adjustments made to just making it a more cozy space.”

Participants also discussed changing the layout of the work place to accommodate physical or cognitive limitations due to symptoms. For example, a participant reduced the walking distance: “I got a printer for my office so I don’t have to walk, my feet hurt.”

Other work strategies mentioned by the participants included asking for others’ help when encountering difficulties, and slowing down the pace of doing tasks. For example: “Like if it was at the end of the day, and if it was a real challenging job that had, or, you know, client that we had, or patient that we had to do a procedure on, I would sometimes ask the other gal to step in”. “I just slowed down the amount of phone calls I would take a day.”

3.4. Importance of work and availability of support

Most participants (n = 26, 76.47%) perceived work being important due to autonomy, distraction, wellbeing, financial, love of the job, mental challenge, normalcy and social aspects. Only 8 participants (23.53%) reported work was not important to them compared with other life issues. While majority of survivors reported that they received sufficient support during active treatment, a few participants reported that they did not receive enough support. Participants reported that some individuals at work were not as supportive as they expected. Conversely, a small number of participants reported they received too much support at work.

4. Discussion

The objective of this paper was to qualitatively describe the barriers, facilitators, and strategies that breast cancer patients experienced while working during active curative-intent treatment with emphasis on the importance of work and availability of support. Even though breast cancer survivors encountered various barriers during active treatment, facilitators and strategies were implemented to overcome these identified barriers to influence continuation of work. The findings are consistent with previous RTW studies in that the impact of treatment and treatment-related symptoms (such as fatigue, pain, decreased mobility, sleep problems) and emotional distress were the main barriers impacting ability to work [4, 29–33]. These barriers affected both returning to work after active treatment, as well as continuing to work during active treatment. Our results suggest that physical work demands, high cognitive demands, frequent traveling, high job stress, and lack of flexibility were the most frequently reported barriers in the workplace. Similarly, these factors have proved to negatively impact RTW time and RTW rate after cancer treatment in previous studies [23, 34, 36].

Perhaps more importantly, barriers were identified that specifically related to work during active treatment. The disruption to work schedule due to cancer treatment appointments was a major barrier for participants who worked during active treatment, which is consistent with previous studies [36]. Even though some participants did not experience severe symptoms, they still encountered time constraints due to medical appointments. Therefore, a flexible work schedule would be important for breast cancer survivors that work during active treatment. Several participants recognized the emotional impact of a cancer diagnosis as an added barrier to working during active treatment. Patients newly diagnosed with cancer faced the emotional impact of the diagnosis, and felt vulnerable [37]. Associations have been found between early return to work and use of coping strategies [38]. The emotional response emanating from diagnosis and treatment made it difficult for breast cancer survivors to concentrate on work related tasks. Individuals needed time to process the emotional response to a cancer diagnosis. Another barrier identified was unwanted appearance change, which has been identified as an important issue for cancer survivors’ quality of life in previous research [39–41]. It was recognized by participants in this study as a barrier that impacted their interactions at work.

Despite various barriers that emerged from working during active treatment, participants were motivated to continue working for diverse reasons. Financial and insurance needs, distraction from cancer and its treatment, and social connections at work were all motivating factors that were frequently reported from the participants. These findings are consistent with previous studies on motivation for returning to work after cancer treatment [4–6, 42, 43].

In addition to these motivating factors, facilitators such as work support from supervisors and coworkers may be necessary for breast cancer survivors that are continuing to work during active treatment. Supervisors can help to facilitate reduced workload, reduced work hours, and doing fewer physically demanding tasks. All of which were found to be important facilitators of working in this study. At the same time, support from outside of the workplace, such as emotional and financial support from family and friends, could benefit working indirectly. Family and friends were able to help participants with both physical and emotional needs. Some participants mentioned friends who were willing to drive them to work. Some reduced activity at home in order to preserve energy for work. These results are consistent with other studies that have found that support from family and friends [44], as well as from supervisors and coworkers [31] can improve the overall quality of life of cancer survivors.

Moreover, our findings also suggested the critical influence that supervisors and coworkers can have on an individual continuing to work during active treatment. In this study, some participants perceived that they needed greater workplace support while some survivors felt they were overprotected by coworkers and supervisors. It may be that supervisors and coworkers lack knowledge on how to provide appropriate support for cancer survivors [31].

Setting limits at work based on employee’s current capacity is not easy [45]. It may be difficult for breast cancer survivors to know their current work capacity and request appropriate accommodations. Although the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Job Accommodation Network provided examples of accommodations that the employers could provide for cancer survivors, it may be difficult to decide the appropriate individual accommodations needed. Furthermore, research has found that survivors may be reluctant to approach employers about employment related issues and accomodations [46]. Improving communication between cancer survivors, coworkers and supervisors would potentially address this problem. Better guidance and support for supervisors and coworkers on how to provide accommodations to fit the cancer survivor’s unique situation may also be needed.

Participants in this study report numerous strategies employed to be able to work during treatment including: adjusting work schedule, performing or altering tasks, working at home, reducing non-work related activities, and reorganizing work related tasks. These findings are similar to the findings of Sandberg et al. [47] but they found participants reduced non-work-related physical activities at the workplace, such as remaining at the office during lunch breaks, as a strategy to conserve energy. In comparison, the participants in the current study reported reducing physical activities in both the workplace and home to conserve energy, such as reducing social activities or hiring a housekeeper to clean the house. Participants also reported concentrating on maintaining their physical health (e.g., exercise, diet) as an indirect way to improve their ability to work.

The findings of this study revealed the important role of technology and tools in working during active treatment, which has been underexplored in previous studies. Inability to use technologies or tools due to cancer treatment and symptoms was a barrier to continued working. For example, blurry vision from chemotherapy made it hard to read the computer screen; neuropathy made it hard to use a washing machine. However, using new technology to facilitate work or changing the tools to aid work may significantly improve the ability to work for breast cancer survivors during active treatment. Especially for breast cancer survivors who have physically demanding work, adjusting or using new technology or tools may provide safe and efficient ways to perform work tasks. For example, arm morbidity can affect work productivity in breast cancer survivors [48]. Computer input devices that are designed to accommodate may improve productivity. However, supervisors, coworkers and breast cancer survivors may need support and guidance about how to use technology or tools to accommodate symptoms and facilitate work.

Findings of this study should be interpreted with caution given some of the limitations. All participants were Caucasian and had higher socioectonomic status (28.6% had post-graduate degrees and 61.8% exceeded household income of $75,000). Thus, they may have had more resources available to assist with work than many breast cancer survivors. However, the present study is one of the few to describe how women manage work while undergoing active treatment for breast cancer. In addition, data were collected while women were participating in active treatment reducing the problem of recall bias. Future studies exploring barriers, facilitators, and strategies should address the experiences of a more diverse population, including survivors of various types of cancer.

The work provided from this study exhibits a detailed picture of barriers, facilitators, and strategies that breast cancer survivors experienced while working during active treatment. Results from this study may assist breast cancer survivors in identifying work related problems and providing a basis for guidance and facilitators to use for working during active treatment. This may potentially benefit employers and oncologists assisting breast cancer survivors who work during active treatment.

5. Conclusion

In summary, even though breast cancer survivors encountered various barriers during active treatment, facilitators and strategies assisted with overcoming barriers. Importantly, inability to use technologies or tools was a barrier to continued working. Collectively, our findings support the need for detailed instructions for both cancer survivors and employers on how to set up an ergonomic work place and guidance on how to use/adjust technology and tools to accommodate symptoms. Additionally, support and guidance on how to request or provide proper work accommodations that match breast cancer survivors’ current capacity may be needed.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this publication were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90IF0083-01-00). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

The authors would also like to thank study coordinators from UWCCC: Sarah Maria Donohue, Tamara Koehn, and Jamie Zeal.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Ekwueme DU, Yabroff R, Guy GP, Banegas MP, De Moor JS, Li C, Han X, Zheng Z, Soni A, Davidoff A, Rechis R, Virgo KS. National Cancer Survivors Medical Costs and Productivity Losses of Cancer Survivors — United States, 2008–2011. Centers Dis Control Prev Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(23) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehnert A, de Boer A, Feuerstein M. Employment challenges for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(Suppl):2151–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amir Z, Neary D, Luker K. Cancer survivors’ views of work 3 years post diagnosis: A UK perspective. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(3):190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nachreiner NM, Dagher RK, McGovern PM, Baker BA, Alexander BH, Gerberich SG. Successful return to work for cancer survivors. AAOHN J. 2007;55(7):290–5. doi: 10.1177/216507990705500705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunfeld EA, Cooper AF. A longitudinal qualitative study of the experience of working following treatment for gynaecological cancer. Psychooncology. 2012;21(1):82–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamminga SJ. Enhancing return to work of cancer patients. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(9):639–848. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen JA, Feuerstein M, Calvio LC, Olsen CH. Breast cancer survivors at work. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(7):777–84. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318165159e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol Elsevier Ireland Ltd. 2011;77(2):109–30. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Short PF, Vasey JJ, Tunceli K. Employment pathways in a large cohort of adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1292–301. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bains M, Munir F, Yarker J, Steward W, Thomas A. Return-to-work guidance and support for colorectal cancer patients: A feasibility study. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34(6):E1–E12. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31820a4c68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taskila T, Martikainen R, Hietanen P, Lindbohm M-L. Comparative study of work ability between cancer survivors and their referents. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(5):914–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: Age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(1):82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, Davis WW, Brown ML. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: Findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(17):1322–30. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smedby KE. Cancer survivorship and work loss–what are the risks and determinants? Acta Oncol. 2014;53(6):721–3. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.913103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duijts SFA, Egmond MP, Spelten E, Muijen P, Anema JR, Beek AJ. Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23(5):481–92. doi: 10.1002/pon.3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velthuis MJ, Agasi-Idenburg SC, Aufdemkampe G, Wittink HM. The effect of physical exercise on cancer-related fatigue during cancer treatment: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) Elsevier Ltd. 2010;22(3):208–21. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nerenz DR, Leventhal H, Love RR. Factors contributing to emotional distress during cancer chemotherapy. Cancer. 1982;50(5):1020–27. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820901)50:5<1020::aid-cncr2820500534>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiedtke C, de Rijk A, Donceel P, Christiaens M-R, de Casterlé BD. Survived but feeling vulnerable and insecure: A qualitative study of the mental preparation for RTW after breast cancer treatment. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:538. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: A population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1608–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo Z. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):345–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steiner JF, Cavender TA, Main DS, Bradley CJ. Assessing the impact of cancer on work outcomes: What are the research needs? Cancer. 2004;101(8):1703–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips KM, McGinty HL, Gonzalez BD, Jim HSL, Small BJ, Minton S, Andrykowski MA, Jacobsen PB. Factors associated with breast cancer worry 3 years after completion of adjuvant treatment. Psychooncology. 2013;22(4):936–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taskila T, Lindbohm ML. Factors affecting cancer survivors’ employment and work ability. Acta Oncol. 46(4):446–51. doi: 10.1080/02841860701355048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stergiou-Kita M, Grigorovich A, Tseung V, Milosevic E, Hebert D, Phan S, Jones J. Qualitative meta-synthesis of survivors’ work experiences and the development of strategies to facilitate return to work. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(4):657–70. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0377-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vachon MLS. Meaning, spirituality, and wellness in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(3):218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauver D, Connolly-Nelson K, Vang P. Stressors and coping strategies among female cancer survivors after treatments. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(2):101–11. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000265003.56817.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beusterien K, Tsay S, Gholizadeh S, Su Y. Real-world experience with colorectal cancer chemotherapies: Patient web forum analysis. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013;7:361. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2013.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lebel S, Rosberger Z, Edgar L, Devins GM. Predicting stress-related problems in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res Elsevier Inc. 2008;65(6):513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groeneveld IF, de Boer AGEM, Frings-Dresen MHW. Physical exercise and return to work: Cancer survivors’ experiences. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(2):237–46. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleming L, Gillespie S, Espie CA. The development and impact of insomnia on cancer survivors: A qualitative analysis. Psychooncology. 2010;19(9):991–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamminga SJ, de Boer AGEM, Verbeek JHaM, Frings-Dresen MHW. Breast cancer survivors’ views of factors that influence the return-to-work process–a qualitative study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2012;38(2):144–54. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy F, Haslam C, Munir F, Pryce J. Returning to work following cancer: A qualitative exploratory study into the experience of returning to work following cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007;16(1):17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Main DS, Nowels CT, Cavender TA, Etschmaier M, Steiner JF. A qualitative study of work and work return in cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2005;1004(December 2004):992–1004. doi: 10.1002/pon.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spelten ER, Sprangers MAG, Verbeek JHaM. Factors reported to influence the return to work of cancer survivors: A literature review. Psychooncology. 2002;11(2):124–31. doi: 10.1002/pon.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carlsen K, Dalton SO, Diderichsen F, Johansen C. Risk for unemployment of cancer survivors: A Danish cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(13):1866–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munir F, Yarker J, McDermott H. Employment and the common cancers: Correlates of work ability during or following cancer treatment. Occup Med (Lond) 2009;59(6):381–9. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weisman AD. Early diagnosis of vulnerability in cancer patients. Am J Med Sci LWW. 1976;271(2):187–96. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197603000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnsson A, Fornander T, Rutqvist L-E, Olsson M. Work status and life changes in the first year after breast cancer diagnosis. Work. 2011;38:337–46. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2011-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, West MM. Adult cancer survivors: How are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104(11 Suppl):2565–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas-maclean R. Feminist Understandings of Embodiment and Disability: A “Material-Discursive”. Approach to Breast Cancer Related Lymphedema. 2005:92–103. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:523–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamminga SJ, de Boer aGEM, Verbeek JHaM, Frings-Dresen MHW. Return-to-work interventions integrated into cancer care: A systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(9):639–48. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rasmussen DM, Elverdam B. The meaning of work and working life after cancer: An interview study. Psychooncology. 2008;17(12):1232–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffman MA, Lent RW, Raque-Bogdan TL. A Social Cognitive Perspective on Coping With Cancer: Theory, Research, and Intervention. Couns Psychol. 2012;41(2):240–67. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noordik E, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Varekamp I, van der Klink JJ, van Dijk FJ. Exploring the return-to-work process for workers partially returned to work and partially on long-term sick leave due to common mental disorders: A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 33(17–18):1625–35. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.541547. 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy KM, Markle MM, Nguyen V, Wilkinson W. Addressing the employment-related needs of cancer survivors. Work Journal. 2013;46:423–32. doi: 10.3233/WOR-131678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandberg JC, Strom C, Arcury TA. Strategies Used by Breast Cancer Survivors to Address Work-Related Limitations During and After Treatment. Womens Health Issues Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health. 2014;24(2):e197–e204. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quinlan E, Thomas-MacLean R, Hack T, Kwan W, Miedema B, Tatemichi S, Towers A, Tilley A. The impact of breast cancer among Canadian women: Disability and productivity. Work Journal. 2009;34:285–96. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2009-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]