Abstract

This study introduces a novel class of imidazolium- and ammonium-based ionic liquids possessing two C12 and C14 tails and thioether linkers designed for lipoplex-mediated DNA delivery. Imidazolium-based ionic liquids displayed efficient gene delivery properties with low toxicity. Thiol-yne click chemistry was employed for the facile and robust synthesis of these thioether-based cationic lipioids with enhanced lipophilicity and low fluidity.

Graphical abstract

Novel lipidic ionic liquids with imidazolium headgroups (red), thioether linkers (black), and two hydrophobic tails (blue) as efficient gene transfection vectors, synthesized via thiol-yne click chemistry

Synthetic gene delivery vectors can serve as viable alternatives to viral vectors due to their reduced immunogenicity and cytotoxicity.4 Synthetic gene carriers including liposomes and lipoplexes are commonly formed with cationic lipids. Analogous to the structures of cell membrane lipids, cationic lipids consist of three critical structural subcomponents – a headgroup, a linker and a hydrophobic domain. A headgroup (e.g. ammonium, imidazolium and etc.), provides a locus of cationic charge and forms the electrostatic binding with DNA/RNA. Its cationic character facilitates the biosolubility of the self-assembled liposome, an attribute further enhanced by the commonly hard, hydrophilic nature of the counter ions. Cationic transfection agents are invariably paired with hydrophilic anions that enhance the interaction of the liposome with water. In turn, a linker provides a secondary means by which the transfection agent can interact with water, while linking the hydrophilic headgroup to the third structural subcomponent, lipidic tails. The latter consists of two saturated/unsaturated aliphatic chains, tethered to glyceryl moiety via a polar ether or ester link. The hydrophobic association of these tails in conjunction with the hydrophilic head leads to the subsequent self-assembly of the liposome, which generates a lipid bilayer capable of complexing with the negatively-charged phosphate backbone of DNA to formlipoplexes.5,6

Felgner et al. first described liposomes, self-assemblies of lipid-inspired amphiphiles that “interact with DNA spontaneously, fuse with tissue culture cells, and facilitate the delivery of functional DNA into the cell.”7 Since the development of DOTMA,7 various liposomal vectors have been developed via systematic variation of the distinct structural domains for the optimized delivery of nucleic acids into eukaryotic cells.6

Aromatic heterocycles (e.g. imidazolium) in cationic lipids exhibit well-balanced polar domains for packaging and releasing of nucleic acids, which is required for efficient gene transfection.8 The positive charge delocalization throughout the heterocyclic moiety leads to increased hydrophobicity in the polar head, which benefits the self-assembling ability of amphiphiles relative to the ammonium cations. The larger and charge-distributed heterocyclic headgroups with hydrophobic tails generate improved packing parameters (P∼ 1), enabling the formation of well-packed lamellar structures that bestows stability to lipoplexes within harsh in vivo enviroment.8

Aromatics were previously incorporated in to the structures of cationic amphiphiles, bridging the polar and nonpolar domains, to improve lipophilicity and self-assembly.9 However, Ilies et al. reported that cationic lipids with aliphatic linkers exhibit higher transfection efficacy and lower toxicity in comparison to their congeners with aromatic backbones.10 Relative position between cationic headgroups and hydrophobic chains on the backbone influences intravenous transfection activity. Ren et al. reported that higher activity was displayed among DOTMA analogs when the cationic headgroup and aliphatic tails are connected through two vicinal oxyalkyl tails at C2 and C3 positions of the backbone.11 Recently, Savarala et al. reported that the extension of the hydrophobic domains in the dopamine-derived cationic lipids led to greater transfection efficacy. In this regard, the oil/water interface was moved to the level of headgroup by effectively incorporating a more lipophilic linker and anion such as ether and [PF6-], respectively.12 However, the [PF6-] anion hydrolyzes in aqueous media and releases HF,13 which would raise toxicity and stability concerns, particularly when searching for transfection vectors.

There is structural congruence between DOTMA-type transfection agents and lipidic ionic liquids; however, the differences that are likely to impact their comparative liquefaction behavior seem more apparent. Lipid icionic liquids are a subclass of ionic liquids (ILs) that utilize structural features similar to natural lipids to introduce lipophilic structural elements while ensuring that their melting points (Tm) remain <100°C.14 Whereas the ILs have relatively large, charge-diffuse cationic head groups (generally thought to favor lower liquefaction temperatures), those in the DOTMA-type cations are more compact and charge localized. Second, the reported low-melting thioether-based ILs possess a single long aliphatic tail rather than two as in the transfection agents.

This study introduces novel lipidic ILs as lipoplex-mediated DNA delivery vectors, prepared via thiol-yne click chemistry in quantitative yields (Scheme 1). The synthesized salts are capable of condensing, packaging and releasing plasmid DNA, proving to be efficient for in vitro DNA delivery in 293T cells, an epithelial line derived from human kidney tissue. While the overall design follows the paradigm established by the cationic lipid template, the new design involves incorporation of thioether moieties as more lipophilic linkers to move the position of hydrophobic/hydrophilic interface at the level of the headgroup. This would be further stabilized by pairing with a more hydrophilic anion like [Cl−]. For this purpose, we used a facile two-step synthetic strategy based on thiol-yne chemistry for the construction of accurately engineered structures (and subsequent properties) of theimidazolium and ammonium-based ILs with C12 and C14 saturated tails and thioether linkers (Scheme 1, ILs 2, 3, 5 and 6), mimicking the glycerol core of the phospholipids' structure. In particular, the effect of aliphatic tail length is examined to elucidate the efficiency of DNA transfection attributed to these lipidic ILs.[Cl−] counter anion was investigated in the present study due to its proven optimum transfection efficiency/cytoxicity ratio, demonstrated in conjugation with the aromatic head groups.12 Our data provides a promising proof-of-principle that lays the foundation to create a new class of thioether-functionalized cationic lipids as efficient gene transfection vectors.

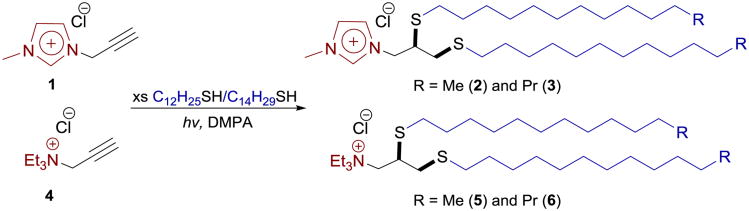

Scheme 1.

Photochemically-induced synthesis of novel lipidic ionic liquids containing imidazolium and ammonium headgroups (red), thioether linkers (black), and two C12 and C14 hydrophobic tails (blue) via thiol-yneclick chemistry.

We previously suggested that a now-popular synthetic paradigm, click chemistry, had much to offer when conceptualizing the synthesis of new functional ions for use in IL formulations.15 We employed the thiol-ene click chemistry in the synthesis of a number of new ILs, most recently species with appended trialkoxysilane and thioether groups.16 Here we report our results on the use of the thiol-yne chemistry, which involves the radical addition of S-H bonds across carbon-carbon triple bonds to access functionalized ILs, containing two thioether groups.

Although the thiol-yne reaction was previously employed for the construction of polyplexes and tertiary amine-derived lipoids,17,18 to our knowledge, the compounds presented here are the first example of the preparation of synthetic cationic lipoids via thiol-yne chemistry as DNA transfection vectors. Additionally, our study demonstrates the first instance of using this chemistry for the preparation of functionalized ILs.

The general strategy employed in this study is the incorporation of two C12 and C14 thioether linkages into the structure of yne–bearing imidazolium (2 and 3) and ammonium (5 and 6) ILs in the presence of a photoinitiator (2,2-dimethoxy-2-acetophenone, DMPA), as indicated in Scheme 1. The thiol-yne reaction was accomplished in a modular single step with minimal requirements for the work-up process. Since no by-products are generated during the consecutive alkylation and thiol-yne coupling, the process does not involve the use of chromatographic purification methods and halogenated solvents for work-up process. Novel thioether-functionalized amphiphilic ILs (2, 3, 5 and 6) were formed as white crystalline solid in quantitative yields. Complete addition of thiols was readily determined by the loss of alkyne signals of 1 and 4 in 1H and 13C NMR spectra (see ESI).

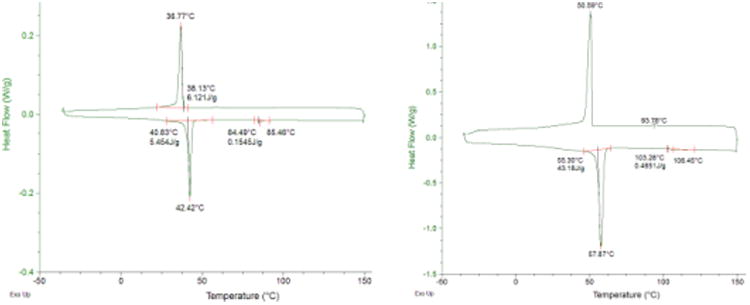

The Tm values of the products were determined by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) with a heating/cooling rate of 10°C/min (Figure 1). The Tm values of 2, 3, 5 and 6 are 40.8°C, 55.3°C, 27.7°C and 38.20°C, respectively, which provide a solid basis for their description as ILs. ILs 2 and 3 display transitions at 84.5°C and 103.3°C (Tiso), respectively that are clearly attributed to the formation of the liquid crystalline phase (Figure 1). This is mainly due to the strong ionic interactions, H-bonding and van der Waals forces between the chains. The structure of the hydrophobic domain determines the phase transition temperature and the fluidity of the bilayer. Comparison of the Tm values of 2, 3, 5 and 6 versus the analogs with saturated C12 and C14 tails allows for the ready identification of some key structure−property relationships. First, the depression of Tm achieved by the introduction of sulfur atoms in the lipophilic side chain is profound; that premise formed the basis for our earlier study. Moreover, side-chain branching is another structural feature of the new ILs that appears to have an important impact upon Tm. We acquired compelling evidence that the collective Tm-depressing effect of a sulfur atom and a methyl branch in the long side-chains of imidazolium ILs brings about substitutional decrease in Tm values relative to the analogs bearing saturated side chains of the same length.15 Thus, incorporation of two thioether chains into the structures of 2 and 3 led to the dramatic Tm depression with ΔTm of 25.9°C and 16.4°C relative to imidazolium IL references, containing C16 (Tm = 66.7°C) and C18 (Tm = 71.7°C) saturated sidechains.19

Figure 1.

DSC traces of 2 (left) and 3 (right).

In order to evaluate the stability versus decomposition, a thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed by heating the sample (10°C/min) from room temperature to 400°C. 2, 3, 5 and 6 are thermally stable up to 264.5°C and 239.7°C, 235.3°C and 239.68°C, respectively where 5% mass loss is reached (see ESI).

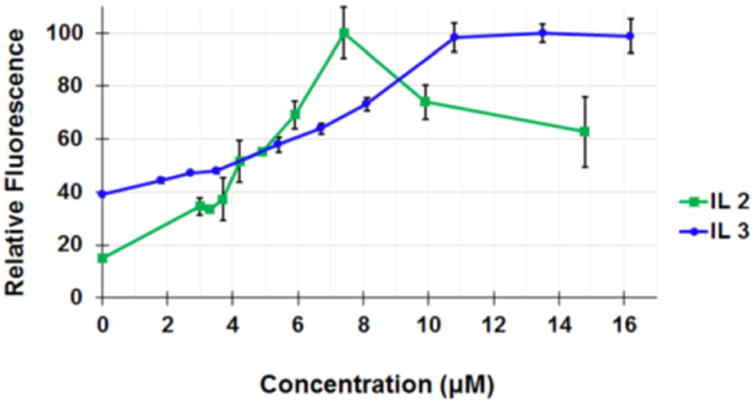

The transfection ability of synthesized ILs were investigated employing a DNA plasmid encoding for green fluorescent protein (pCMVieeGFP) in 293T cells. ILs 2, 3, 5, and 6 were re-suspended at stock concentrations of 8.9, 1.6, 5.2 and 3.1 mM, respectively, in water with up to 10% v/v dimethyl sulfoxide to facilitate solubility. Poly-L-lysine (PLL) at a concentration of 8.6 × 10-6μM in water was used to condense approximately 2 μg pCMVieeGFP. The condensed plasmid was then combined with ILs of various dilutions to determine the best DNA to IL ratio for transfection efficacy. Imidazolium-based ILs (2 and 3) were identified as positive “hits” (Figure 2); however, the ammonium counterparts (5 and 6) exhibited no clear trend of transfection activity (ESI, Figure S7). Our initial hypothesis was that better transfection agents encompass stronger electrostatic interaction with DNA as a presumptive key step in gene delivery. As shown here, support for this explanation was obtained by the correlation of transfection activity of imidazolium-based lipoids (which induce the biggest local bilayer anisotropy via the structure of a large charge-distributed cation) relative to the ammonium analogs. IL 2 is the more efficient vector in terms of transfection efficiency/cytotoxicity ratios due to their higher fluidity generated via the presence of shorter hydrophobic domain. To gain further insight into the relative efficacy of the new ILs, transfection of MirusTransIT 293 as a commercially-available gene transfection agent was studied. IL 2 shows ∼35% transfection efficacy in comparison to the Mirus TransIT 293 (ESI, Figure S9). Further investigation to evaluate the potential of this screening library are currently underway.

Figure 2.

Transfection efficacy of 2 and 3, employing plasmid DNA (pCMVieeGFP) in 293T cells.

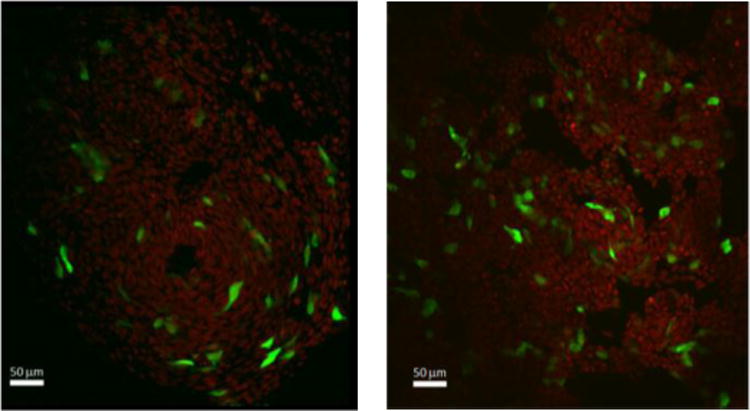

Confocal microscopy was further utilized to observe intracellular distribution of plasmid-expressed GFP in 293T cells. As shown in Figure 3, the fluorescing green cells appear throughout the field of view for transfections using 2 and 3, suggesting efficient cellular uptake of the ILs.

Figure 3.

Confocal microscopy images of 293T cells transfected with pCMVieeGFP using 2 (left) and 3 (right). Plasmid expression in the 293T cellline was observed as green fluorescence. Cell nuclei were counterstained with a far-red dye (646/697 nm ex/em wavelength) DRAQ5 Fluorescent Probe and false colored red to contrast GFP expression.

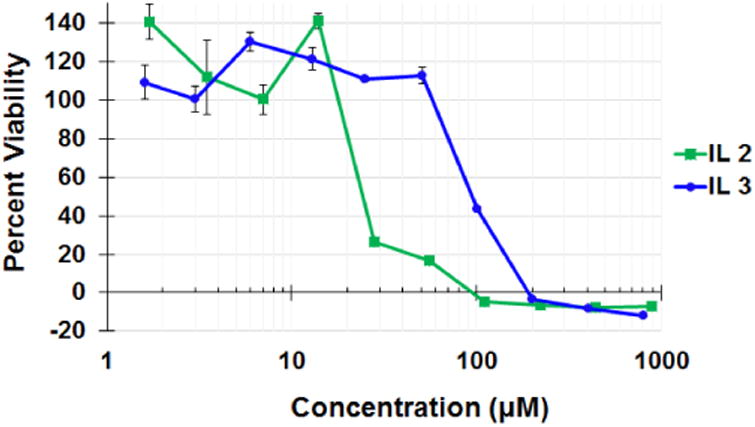

An MTT cell viability assay was performed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of ILs by determining metabolic activity of IL treated HeLa cells, a human derived cervical cancer cell line. To evaluate the extent of IL induced cell death, HeLa cell monolayers were incubated with dilutions of the ILs in complete cell media for 24h and then assessed for viability. ILs 2 and 3 exhibited TC50 of approx. 21 μM and 101μM, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cellular toxicity of IL 2 and 3 in HeLa cells. Cell viability is presented as IL-treated cell absorbance normalized to the absorbance of non-treated cell control. Absorbance measured at 560 nm.

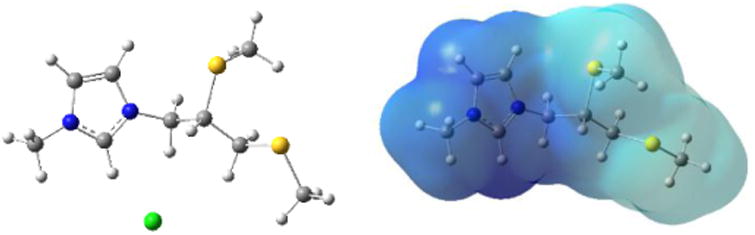

The structures of imidazolium ILs were optimized using the B3LYP exchange–correlation functional and the 6-311++G(d,p) basis set as implemented in the Gaussian09 suite of programs.20 Stable structures were confirmed by computing analytic vibrational frequencies. At the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level, an imidazolium IL has four optimized structures, in which the anion occupies different locations (Figs. 5 and S9). In most stable conformer, the distance between [Cl−] and hydrogen atoms at C2(ring), C1, C2, and C3 atoms amount to 2.088, 2.547, 3.541, 2.893 Å, respectively. This is consistent with the electrostatic surface of imidazolium cation shown in Figure 5, where most positive charges are near the hydrogen atoms of C2(ring). Interestingly, the molecule's polarity and the boundary between hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains can be clearly observed and shows that sulfur atoms are in the hydrophobic area (Figure 5, left). The electrostatic potential energy map of salt demonstrates a strong interaction between the anion and the positively-charged imidazolium ring (ESI, Figure S10).

Figure 5.

Optimized structure of an imidazolium-based IL at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level (left) and the electrostatic potential map of the imidazolium cation (right).

All inter-ion interactions were taken into account by explicitly modeling the IL's structure using DFT computations The HOMO is localized on chloride ion. The LUMO orbital is delocalized on the ring. The transition from HOMO to LUMO is an intramolecular transition, with the HOMO-LUMO gap of 4.40 eV (ESI, Figure S11).

In summary, we have generated a class of new low-melting thioether-based imidazolium ionic liquids useful for DNA-complexing materials for gene delivery. The lipoids not only exhibit mesophase properties but also are promising amphiphilic molecules for DNA delivery. Consistent DNA transfection activity was not observed for their counterparts, containing ammonium headgroup with the same side chains. Indeed, such findings point to the importance of investigating the head group and linker portions of cationic amphiphiles. The major advantages that distinguish our compounds from other vectors are the fact that our click-mediated synthetic procedure is simple, green and cost effective while still producing comparable results. This chemistry is currently being used to optimize the transfection efficacy in anticipation that they ultimately lead to the discovery of materials for applications beyond gene delivery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from NSF CHE−1530959, NIH R01AI099210 (S.I. and S. F. M.), and the Brodie Scholarship from the FGCU Whitaker Center are acknowledged. A.M. is grateful to Prof. Jim Davis from University of South Alabama for the insightful suggestions.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Key MA. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:316. doi: 10.1038/nrg2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mingozzi F, High KA. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:341. doi: 10.1038/nrg2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhi D, Zhang S, Cui S, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Zhao D. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013;24:487. doi: 10.1021/bc300381s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya S, Bejaj A. Chem Commun. 2009:4632. doi: 10.1039/b900666b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montier T, Benvegnu T, Jaffres PA, Yaouanc JJ, Lehn P. Curr Gene Ther. 2008;8:296. doi: 10.2174/156652308786070989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draghici B, Illies M. J Med Chem. 2015;58:4091. doi: 10.1021/jm500330k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, Chan HW, Wenz M, Northrop JP, Ringold GM, Danielsen M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhi D, Zhang S, Cui S, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Zhao D. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013;24:487. doi: 10.1021/bc300381s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobbs W, Heinrich B, Bourgogne C, Donnio B, Terazzi E, Bonnet M, Stock F, Erbacher P, Bolcato-Bellemin A, Douce L. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13338. doi: 10.1021/ja903028f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilies MA, Seitz WA, Ghiviriga I, Johnson BH, Miller A, Thompson EB, Balaban AT. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3744. doi: 10.1021/jm0499763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren T, Zhang YK, Liu D. Gen Ther. 2000;7:764. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savarala S, Brailoiu E, Wunder SL, Ilies MA. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:2750. doi: 10.1021/bm400591d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swatloski RP, Holbrey JD, Rogers RD. Green Chem. 2003;5:361. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirjafari A, O'Brien RA, Davis JH., Jr . Synthesis and properties of lipid-inspired ionic liquids. In: Xu X, Guo Z, Cheong LZ, editors. Ionic Liquids in Lipid Processing and Analysis. Vol. 6. AOCS Press; 2016. pp. 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirjafari A, O'Brien RA, West KN, Davis JH., Jr Chem Eur J. 2014;20:7576. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez Zayas M, Gaitor JC, Nestor ST, Minkowicz S, Sheng Y, Mirjafari A. Green Chem. 2016;18:2443. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z, Yin L, Xu Y, Tong R, Ren J, Cheng J. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:3456. doi: 10.1021/bm301333w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Zahner D, Su Y, Gruen C, Davidson G, Levkin PA. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8160. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley AE, Hardacre C, Holbrey JD, Johnston S, McMath SEJ, Nieuwenhuyzen M. Chem Mater. 2002;14:629. [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648. [Google Scholar]; b) Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Chabalowski CF, Frisch MJ. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:11623. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.