Abstract

Background

There is limited data on how maternal age is related to twin pregnancy outcomes.

Objective

To assess the relationship between maternal age and risk for preterm birth, fetal death, and neonatal death in the setting of twin pregnancy.

Study design

This population-based study of US birth, fetal death, and period linked birth-infant death files from 2007–2013 evaluated neonatal outcomes for twin pregnancies. Maternal age was categorized as 15 to 17, 18 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, and ≥40 years of age. Twin live births and fetal death delivered at 20 to 42 weeks were included. Primary outcomes included preterm birth (<34 weeks and <37 weeks), fetal death, and neonatal death at <28 days of life. Analyses of preterm birth at <34 and <37 weeks were adjusted for demographic and medical factors, with maternal age modeled using restricted spline transformations.

Results

A total of 955,882 twin live births between 2007 and 2013 were included in the analysis. Preterm birth rates at <34 weeks and <37 weeks were highest for women 15 to 17 years of age, decreased across subsequent maternal age categories, nadired for women age 35– 39 and then increased slightly for women 40 or over. Risk for fetal death generally decreased across maternal age categories. Risk for fetal death was 39.9 per 1,000 live births for women age 15 to 17, 24.2 for women age 18 to 24, 17.8 for women age 25 to 29, 16.4 for women age 30 to 34, 17.2 for women age 35 to 39 and, and 15.8 for women 40 or older. Risk for neonatal death <28 days was highest for neonates born to women age 15 to 17 (10.0 per 1,000 live births), decreased to 7.3 for women 18 to 24 and 5.5 for women 25 to 29, and ranged from 4.3 to 4.6 for all subsequent maternal age categories. In adjusted models, risk for preterm birth at <34 to <37 weeks was not elevated for women in their mid-to-late-thirties; however, risk was elevated for women <20 and increased progressively with age for women in their forties.

Conclusion

While twin pregnancy is associated with increased risk for most adverse perinatal outcomes, this analysis did not find advanced maternal age to be an additional risk factor for fetal death and infant death. Preterm birth risk was relatively low for women in their late thirties. Risks for adverse outcomes were higher among younger women and further research is indicated to improve outcomes for this demographic group. It may be reasonable to counsel women in their thirties that their age is not a major additional risk factor for adverse obstetric outcomes in the setting of twin pregnancy.

INTRODUCTION

Extremes of maternal age and twin pregnancy are both independent risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Advanced maternal age (AMA), defined as age 35 or older, is associated with increased risk for spontaneous and indicated preterm birth, fetal death, aneuploidy, and maternal complications.(1–3) Compared to the general population, teenage mothers are at increased risk for adverse outcomes including preterm birth, small for gestational age infant, and neonatal death.(4–6) Twin pregnancy is also a risk factor for preterm birth, fetal death, and multiple other adverse outcomes.(7) Women age 35 or older are more likely to become pregnant with twins, as both increasing parity and fertility treatment increase the risk for multiple gestation.(8, 9)

In recent decades in the United States the proportion of both twin and AMA births has increased.(10) Probability of twin pregnancy may be an important consideration in assisted reproductive technology decision-making, particularly for older infertility patients who desire more than one child.(11) However, there is limited research evidence regarding to what degree extremes of maternal age may be associated with increased risk for adverse outcomes. Data from IVF pregnancies suggests that AMA may not be a risk factor for preterm birth with twins.(12) Linked twin birth-infant death certificates from the 1980s and 1990s demonstrated decreased infant mortality with advancing maternal age.(13) More recent studies and subgroup analyses of twins have generally found that AMA is not associated with increased risk for adverse outcomes;(14–19) however these findings have been limited by the sample sizes of these reports. Data focused on twin pregnancy amongst teenage mothers is limited.(20)

Given that the role of maternal age in relation to twin pregnancy outcomes is not well characterized, we evaluated how risk for adverse outcomes may be affected by this factor. Better knowledge of maternal-age-based outcomes may be of value in preconception counseling for women seeking fertility treatment as well as those with a new diagnosis of twin pregnancy.

METHODS

This population-based analysis of twin pregnancies utilized US birth, fetal death, and period linked birth-infant death files from 2007 to 2013. The primary outcomes of this study were to evaluate the risks of: (i) fetal death; (ii) preterm birth at <34 and <37 weeks; and (iii) neonatal death at <28 days of life. To assess unadjusted neonatal death, preterm birth, and fetal death risk we used data for the entire US population. For adjusted models for preterm birth at <34 and <37 weeks, we restricted data to births reported in the revised 2003 version of the birth certificate; this newer format includes additional obstetric, demographic, and medical data.(21) Because the revised birth certificate was incorporated gradually on a statewide basis, the number of states included in the revised data increased annually and represents an increasing proportion of all US births. States using the revised format numbered 12 in 2005 (31% of all births), 19 in 2006 (49% of all births), 22 in 2007 (53% of all births), 27 in 2007 (65% of all births), 28 in 2009 (66% of all births), 33 in 2010 (76% of all births), 36 in 2011 (83% of all births), 38 in 2012 (86% of all births), and 41 in 2013 (90% of all births); New York City was not included in New York State data from 2005 to 2007 and Washington D.C. was included since 2010.(22)

While the quality and validity of data on birth certificates varies, prior analyses have found obstetric estimate of gestational age to be accurate.(23, 24) We included women between 15 and 50 years of age, and divided maternal age into seven categories: 15 to 17, 18 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, and ≥40 years. For fetal death, the majority of states require reporting based on either a gestational age of 20 weeks or greater or birth weight of 350 grams or greater.(5) To determine the risk of preterm birth, all twin live births from 20 to 41 completed weeks were included, and the proportions of births occurring at <34 weeks and <37 weeks based on the obstetric estimate of gestational age were calculated. To determine the risk of neonatal deaths, US vital statistics linked birth/infant death data was utilized. Within the US vital statistics data, linkage of infant deaths to live births is performed in over 98% of all cases.(6) Risk for neonatal death <28 days of life was calculated by dividing deaths that occurred <28 days by all live births.

For preterm birth at <34 weeks and <37 weeks based on obstetric estimate of gestational age, bivariate analyses for medical and demographic factors including maternal age were performed and then adjusted models were created from twin births reported in the 2003 revised format. In the adjusted models, demographic variables included parity, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic other, and Hispanic), highest level of education (<9th grade through professional degree), and marital status (married or unmarried). Medical factors included preexisting diabetes and chronic hypertension. As US vital statistics data are both publically available and de-identified, this analysis was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Statistical analysis

Bivariate analyses were performed using the χ2 test. Log-linear regression models for preterm birth <34 and <37 weeks in relation to maternal age were developed with risk ratio estimated by using a Poisson regression with robust error variance. Maternal age was modeled using restricted cubic spline transformations. Regression splines are nonparametric smoothing procedures that do not impose any restriction on the shape of distribution between the continuous predictor and the outcome, and this methodology allows flexibility in modeling the non-linear relationship between continuous predictors (maternal age) and the outcome.(25, 26) We elected to use regression splines because of data on risk for adverse outcomes being increased at either end of the maternal age spectrum; if we presumed a linear relationship between the continuous predictor and the outcome we would not be able to appropriately model the relationship. The appropriate number of knots for maternal age in the models was determined based on the likelihood-ratio test.(25) An eight-piece restricted cubic spline with knot locations for maternal age at 19 (4th percentile of the patient population), 24 (21st percentile), 27 (35th percentile), 30 (53rd percentile), 33 (71st percentile), 36 (86th percentile), and 42 (98th percentile) years was applied to the regression models for twin preterm birth <34 and <37 weeks gestational age. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

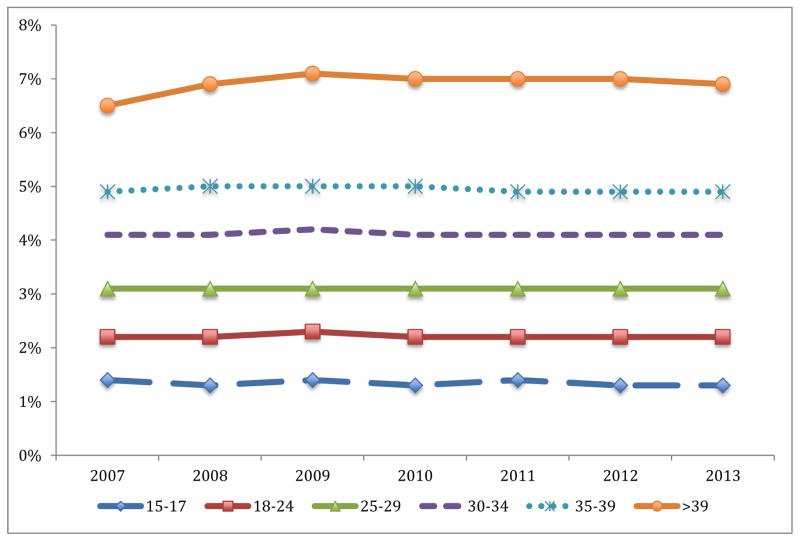

A total of 932,806 live twin births between 2007 and 2013 occurred for the entire US population and were included in the analysis. Of all twin births, 1.1% were born to women 15– 17, 19.8% to women 18–24, 26.1% to women 25–29, 29.6% to women 30–34, 17.5% to women 35–39, and 5.9% to women ≥40. 17,746 fetal deaths were included in the analysis. The proportion of twins of all births (including singletons and other higher order gestation) was relatively stable over the study period for each maternal age category (Figure 1). The probability of twin pregnancy increased with maternal age, with twins accounting for 6.9% of neonates born to women 40 or over, versus 5.0% for women 35 to 39, 4.1% for women 30 to 34, 3.1% for women 25 to 29, 2.2% for women 18 to 24, and 1.3% for women 15 to 17.

Figure 1. Twins as proportion of all neonates by year of birth and maternal age category.

The figure demonstrates the proportion of all live-born neonates for each maternal age category that are twins by year of birth.

Table 1 demonstrates demographic data restricted to 693,236 live twin births reported on the 2003 birth certificate revision. Older maternal age categories were associated with higher levels of education. For example, 30.9% women age 35 to 39 of had a bachelor’s and 19.0% had a master’s degree as highest educational attainment, compared to 21.9% and 7.1% for women age 25 to 29. In terms of parity, women age 30–34 were less likely to have had either one prior delivery or no prior deliveries (parity <2) (52.3%) compared to older women (61.1% for women 40 or older) and younger women (68.0% for women age 18–24). Women 30 or older were more likely to be married, white, and have pregestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, or both.

Table 1.

Demographic factors by maternal age group among twin pregnancies

| Maternal age, years | 15–17, n (%) | 18–24, n (%) | 25–29, n (%) | 30–34, n (%) | 35–39, n (%) | ≥40, n (%) |

|

| ||||||

| All patients | 7,192 | 136,986 | 182,008 | 205,138 | 120,301 | 41,611 |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| ≤8th grade | 489 (6.8) | 4,404 (3.2) | 5,474 (3.0) | 5,477 (2.7) | 3,521 (2.9) | 981 (2.4) |

| 9th–12th grade | 5,689 (79.2) | 28,995 (21.2) | 16,520 (9.1) | 10,064(4.9) | 4,664 (3.9) | 1,018 (2.5) |

| High school | 865 (12.0) | 55,296 (40.4) | 42,411 (23.3) | 29,356 (14.3) | 14,511 (12.1) | 3,929 (9.4) |

| Some College | 0 | 35,318 (25.8) | 42,387 (23.3) | 33,056 (16.1) | 16,271 (13.5) | 4,765 (11.5) |

| Associate Degree | 0 | 5,973 (4.4) | 17,952 (9.9) | 18,065 (8.8) | 9,723 (8.1) | 2,902 (7) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0 | 5,187 (3.8) | 39,883 (21.9) | 62,052 (30.3) | 37,192 (30.9) | 13,287 (31.9) |

| Master’s degree | 0 | 392 (0.3) | 12,854 (7.1) | 33,931 (16.5) | 22,911 (19.0) | 8,450 (20.3) |

| Doctorate | 0 | 48 (0.0) | 2,188 (1.2) | 9,990 (4.9) | 9,022 (7.5) | 4,093 (9.8) |

| Unknown | 99 (1.4) | 1,373 (1.0) | 2339 (1.3) | 3,147 (1.5) | 2,486 (2.1) | 2,186 (5.3) |

| Parity | ||||||

| 0 | 3,745 (52.1) | 39,606 (28.9) | 43,217 (23.7) | 48,171 (23.5) | 26,664 (22.2) | 11,165 (26.8) |

| 1 | 3,002 (41.7) | 53,596 (39.1) | 62,247 (34.2) | 70,029 (28.8) | 40,153 (33.4) | 14,277 (34.3) |

| 2 | 363 (5.1) | 28,196 (20.6) | 40,978 (22.5) | 44,362 (21.6) | 25,843 (21.5) | 7,460 (17.9) |

| ≥3 | 82 (1.1) | 14,488 (11.4) | 35,656 (19.6) | 42,576 (20.8) | 27,641 (23.0) | 8,709 (20.9) |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 364 (5.1) | 44,414 (32.4) | 121,901 (67.0) | 167,493 (81.7) | 101,861 (84.7) | 35,139 (84.5) |

| Not married | 6,828 (94.9) | 92,572 (67.6) | 60,107 (33.0) | 37,645 (18.3) | 18,440 (15.3) | 6,472 (15.6) |

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2,253 (31.3) | 61,718 (45.1) | 108,055 (59.4) | 133,025 (64.9) | 76,667 (63.7) | 27,010 (64.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2,021 (28.1) | 37,539 (27.4) | 30,183 (16.6) | 23,139 (11.3) | 12,010 (10.0) | 3,571 (8.6) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 154 (2.1) | 3,783 (2.8) | 8,708 (4.8) | 15,149 (7.4) | 10,999 (9.1) | 3,799 (9.1) |

| Hispanic | 2,2713 (37.7) | 32,979 (24.1) | 33,471 (18.4) | 31,533 (15.4) | 18,633 (15.5) | 5,404 (13.0) |

| Unknown | 51 (0.7) | 967 (0.7) | 1,591 (0.9) | 2,281 (1.1) | 1,992 (1.7) | 1,827 (4.4) |

| PDM | ||||||

| Present | 26 (0.4) | 689 (0.5) | 1,394 (0.8) | 1,906 (0.9) | 1,318 (1.1) | 467 (1.1) |

| Absent | 7,104 (98.8) | 135,348 (98.8) | 179,708 (98.7) | 202,375 (98.7) | 118,557 (98.6) | 40,974 (98.5) |

| Unknown | 60 (0.8) | 949 (0.7) | 906 (0.5) | 857 (0.4) | 426 (0.4) | 170 (0.4) |

| Chronic HTN | ||||||

| Present | 64 (0.9) | 1,769 (1.3) | 3,237 (1.8) | 4,280 (2.1) | 3,162 (2.6) | 1,496 (3.6) |

| Absent | 7,068 (98.3) | 134,268 (98.0) | 177,865 (97.7) | 200,001 (97.5) | 116,713 (97.0) | 39,945 (96.0) |

| Unknown | 60 (0.8) | 949 (0.7) | 906 (0.5) | 857 (0.4) | 426 (0.4) | 170 (0.4) |

| Year | ||||||

| 2007 | 1,054 (14.7) | 16,414 (12) | 19,699 (10.8) | 20,253 (9.9) | 12,702 (10.6) | 3,894 (9.4) |

| 2008 | 1,151 (16.0) | 18,407 (13.4) | 22,978 (12.6) | 24,037 (11.7) | 15,176 (12.6) | 5,088 (12.2) |

| 2009 | 1,148 (16.0) | 18,969 (13.9) | 23,669 (13.0) | 25,531 (12.5) | 15,184 (12.6) | 5,429 (13.1) |

| 2010 | 1,032 (14.4) | 19,812 (14.5) | 26,344 (14.5) | 29,260 (14.3) | 17,327 (14.4) | 6,076 (14.6) |

| 2011 | 1,066 (14.8) | 21,316 (15.6) | 28,962 (15.9) | 33,424 (16.3) | 19,013 (15.8) | 6,784 (16.3) |

| 2012 | 910 (12.7) | 20,930 (15.3) | 29,414 (16.2) | 35,678 (17.4) | 20,150 (16.8) | 7,129 (17.1) |

| 2013 | 831 (11.6) | 21,138 (15.4) | 30,942 (17.0) | 36,955 (18.0) | 20,749 (17.3) | 7,211 (17.3) |

Comparisons for all demographic and medical variables differed significantly by maternal age category (p <0.001). PDM, pregestational diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension. Demographics were calculated based on data reported in the 2003 revised birth certificate format.

Table 2 demonstrates rates of preterm birth, fetal death, and neonatal death by maternal age categories for the entire US population. Preterm birth risk at <34 weeks and <37 weeks were highest for women 15 to 17 years of age, decreased across subsequent maternal age categories, nadired for women age 35–39 and then increased slightly for women 40 or over. For example, the risk of preterm birth for <34 weeks gestational age was 32.7% for women age 15 to 17, decreased to 18.4% for women age 35 to 39, and was 20.5% for women 40 or older. The risk of preterm birth <37 weeks was 67.7% for women age 15 to 17, 56.1% for women age 35–39, and 58.1% for women 40 or older. Risk for fetal death generally decreased across maternal age categories. Risk for fetal death was 39.9 per 1,000 births for women age 15 to 17, 24.2 for women age 18–24, 17.8 for women age 25 to 29, 16.4 for women age 30 to 34, 17.2 for women age 35 to 39 and, and 15.8 for women 40 or older. Similarly, risk for neonatal death <28 days was highest for neonates born to women age 15 to 17 (10.0 per 1,000 live births), decreased to 7.3 for women 18 to 24 and 5.5 for women 25 to 29, and was then lower for all subsequent maternal age categories.

Table 2.

Pregnancy, neonatal, and infant outcomes among twins by maternal age group

| Maternal age range, years | 15–17 | 18–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35–39 | ≥40 |

|

| ||||||

| Preterm birth, % (n) | ||||||

| <34 weeks | 32.7 (3,208) | 24.6 (45,432) | 20.5 (48,896) | 18.7 (51,515) | 18.4 (29,989) | 20.5 (11,271) |

| <37 weeks | 67.7 (6,641) | 61.6 (113,942) | 58.9 (143,456) | 56.6 (156,027) | 56.1 (91,565) | 58.1 (31,968) |

|

| ||||||

| Fetal deaths, rate (n)* | 39.9 (408) | 24.2 (4,597) | 17.8 (4,406) | 16.4 (4,591) | 17.2 (2,859) | 15.8 (885) |

|

| ||||||

| Neonatal death <28 days, rate (n)# | 10.0 (98) | 7.3 (1,352) | 5.5 (1,342) | 4.3 (1,195) | 4.6 (751) | 4.3 (237) |

Fetal death rate calculated per 1,000 births (live births and fetal deaths).

Neonatal death rate <28 days calculated per 1,000 live births. All outcomes in this table were calculated using a full population of US natality data (2003 revised and unrevised birth certificate).

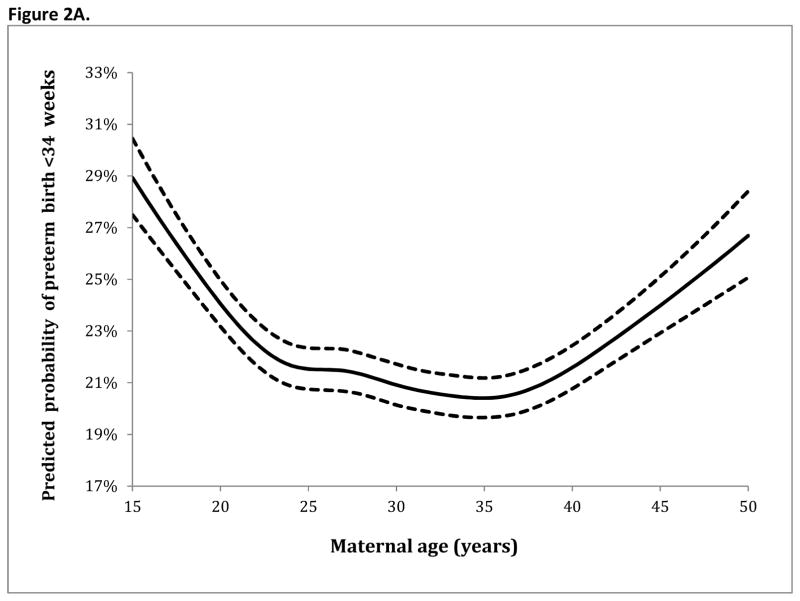

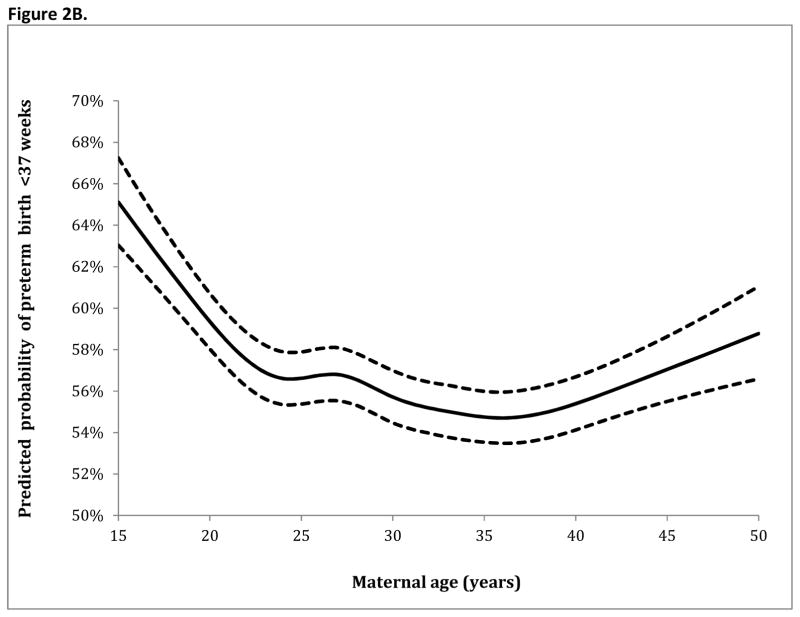

Table 3 demonstrates the adjusted analyses for preterm birth at <34 and <37 weeks. Factors associated with increased rates of preterm birth at both <34 weeks and <37 weeks included: Black race (with white race as a referent) (RR 1.22 95% CI 1.20–1.24, RR 1.04 95% CI 1.03–1.05, respectively), pregestational diabetes (RR 1.34 95% CI 1.28–1.41, RR 1.14 95% CI 1.11–1.18), and chronic hypertension (RR 1.25 95% CI 1.21–1.29, RR 1.18 95% CI 1.16–1.21). Parity >0 was associated with decreased risk of preterm birth <34 weeks. With maternal age analyzed as a continuous variable (based on spline transformation), the adjusted analysis for preterm birth at <34 weeks and <37 weeks gestational age are demonstrated in Figure 2A and Figure 2B, respectively. For preterm birth at <34 weeks and <37 weeks in the adjusted model, risk (demonstrated in the figures) was highest for the youngest women with risk then decreasing and nadiring at age 36 before rising again for older women.

Table 3.

Adjusted models for twin preterm birth at <34 weeks and <37 weeks

| Preterm birth cutoff | <34 weeks | <37 weeks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Risk ratio | 95% CI | Risk ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Parity | 0 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 1 | 0.87 | (0.86–0.88) | 0.96 | (0.95–0.97) | |

| 2 | 0.75 | (0.74–0.76) | 0.93 | (0.92–0.94) | |

| ≥3 | 0.82 | (0.81–0.84) | 0.96 | (0.95–0.97) | |

| Education | ≤8th grade | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| 9th–12th grade | 1.11 | (1.07–1.15) | 1.07 | (1.05–1.10) | |

| High school | 1.05 | (1.01–1.08) | 1.07 | (1.05–1.10) | |

| Some College | 1.00 | (0.97–1.04) | 1.08 | (1.06–1.10) | |

| Associate Degree | 0.99 | (0.95–1.03) | 1.08 | (1.05–1.10) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.93 | (0.90–0.96) | 1.03 | (1.01–1.05) | |

| Master’s degree | 0.91 | (0.87–0.94) | 1.02 | (1.00–1.04) | |

| Doctorate | 0.91 | (0.87–0.95) | 1.04 | (1.01–1.06) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Not married | 1.09 | (1.07–1.10) | 1.01 | (1.00–1.02) | |

| Race | Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.22 | (1.20–1.24) | 1.04 | (1.03–1.05) | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 0.94 | (0.92–0.97) | 0.95 | (0.93–0.96) | |

| Hispanic | 0.99 | (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 | (0.98–1.00) | |

| Pregestational DM | Present | 1.34 | (1.28–1.41) | 1.14 | (1.11–1.18) |

| Chronic HTN | Present | 1.25 | (1.21–1.29) | 1.18 | (1.16–1.21) |

| Infant gender | Male | 1.05 | (1.04–1.06) | 1.02 | (1.01–1.02) |

| Female | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |

DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension. For pregestational diabetes and chronic hypertension the risk ratios are presented with the absence of the condition as the reference

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. Spline regression model for preterm birth <34 weeks gestational age

Figure 2B. Spline regression model for preterm birth <37 weeks gestational age

The solid line demonstrates the estimated risk for preterm birth within the regression models at <34 and <37 weeks gestational age with knot locations at maternal ages of 19 (4th percentile of the age distribution), 24 (21st percentile), 27 (35th percentile), 30 (53rd percentile), 33 (71st percentile), 36 (86th percentile), and 42 (98th percentile). The dashed lines represent the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study suggest that while extremes of maternal age may be associated with increased risk for preterm birth among twin pregnancies, the risks for fetal death and neonatal death were generally lower for older women than the rest of the population. Furthermore, women in their mid-to-late 30s had the lowest risks of preterm birth at <34 weeks and <37 weeks, with risk for women in their early forties similar to that of women in their early twenties. Given that nearly three quarters of AMA twins were to women age 35 to 39, these findings suggest that for the majority of AMA pregnancies, maternal age will not be a major risk factor for adverse outcomes including preterm birth. Conversely, risk for adverse outcomes including preterm birth, fetal death, and neonatal birth was higher for the youngest women who were the highest risk patients in this cohort.

Interpretation of findings

These findings support previous analyses demonstrating that AMA in the setting of twin pregnancy is associated with outcomes similar to the general population.(7, 13, 14, 19) An important question in research on singleton outcomes is whether maternal age is an independent and direct risk factor for preterm birth, or whether the associations seen are due primarily to comorbid risk factors.(27) It is possible that the similar age-based risk in this analysis is due to women becoming pregnant with twins in their mid-thirties or forties being a self-selected group with otherwise good health and favorable obstetric factors. The cause of higher risk for adverse outcomes amongst younger women is unclear; our analysis was not able to assess determinants of social support and socioeconomic status other than marriage and education, and it may be that there are specific barriers to optimal care for women age 15 to 17. For high-risk pregnancies such as those complicated by multiple gestation, good quality prenatal care may obviate more risk than for low risk singletons. Addressing social barriers may be critical in reducing fetal death risk for adolescents.(28) For these at-risk women, increased surveillance may be warranted. We note that the additional adjusted risk for preterm birth <34 weeks for black women is below that demonstrated by other analyses.(22) This may be secondary to changes in risk for this population, more extensive modeling of the effect of maternal age, or unmeasured confounding (such as zygosity). Future research is indicated on preterm birth prevention strategies for twins given lack of validated strategies to reduce risk for these pregnancies. Close follow up during prenatal care and application of models that detect risk for preterm birth may lead to improved outcomes.

An important consideration of this analysis is that while these findings may be reassuring for AMA women with twin pregnancy, it is important to note that our findings demonstrate that overall twin pregnancies is associated with increased risk for preterm birth, fetal death, and neonatal death, and that outcomes for singleton pregnancy are significantly better.(29) Furthermore, increased risk for preterm birth <34 weeks was noted as women progressed towards their mid-forties.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Strengths of the study include: (i) a national sample of women with information on the primary outcomes of preterm birth, (ii) likely high quality data for gestational age,(23, 24) fetal death, neonatal death and maternal demographics such as age, (iii) the relatively long study period (7 years), and (iv) use of spline methodology that allows the effect of maternal age to be characterized in a non-linear manner.

Study limitations include: (i) limited covariates describing maternal and obstetric characteristics including socioeconomic status; (ii) that specific pregnancy factors such as chorionicity are not included in the natality data; (iiI) for fetal deaths multivariable analysis is not possible given that data is further restricted in terms of demographic and medical data; (iv) that some birth certificate characteristics relevant to the outcomes, such as congenital anomalies, use of assisted reproductive technology, and body mass index were not included in the analysis due to concern for poor sensitivity;(30) (v) that fetal deaths and delivery prior to 20 weeks was not evaluated and risk for adverse outcomes at these gestational may follow a different distribution by maternal age; (vi) that antenatal surveillance regiments are not included in the data, (vii) that obstetric interventions such as antenatal corticosteroids, baby aspirin, cerclage, and progesterone are not included in the data, and (viii) an analysis that takes the non-independence of outcomes within a twin sibship is not possible given that twins cannot be linked in the data set including evaluating risks of fetal death on a co-twin. That chorionicity is not included is a significant limitation; mono-chorionicity may be associated with increased risks for both preterm birth and major structural anomalies.(31) Given that parity >0 was associated with decreased risk for twin preterm birth <34 weeks, this factor may serve as a proxy that accounts in part for prior term (as opposed to preterm) birth. Because twins within a sibship could not be differentiated and listed birth certificate indications for delivery may have differed by birth certificate for the two fetuses within a twin pregnancy, we were not able to distinguish between indicated and spontaneous preterm birth. Given the large numbers of twins included in the analysis, some statistically significant differences may not be representative of meaningful clinical differences.

In summary, while twin pregnancy is associated with increased risk for most adverse obstetric outcomes, this analysis did not find advanced maternal age to be a significant additive risk factor for fetal death and neonatal death. Preterm birth rates were comparable to the general population (or lower) for women age 35–39. In comparison, the youngest mothers – those age 15–17 – were at highest risk for all adverse outcomes. It may be reasonable to counsel most AMA patients without other major obstetrical risk factors that after 20 weeks gestational age their prognosis during a twin pregnancy is similar to that of the general population.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Friedman is supported by a career development award (K08HD082287) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

The study authors would like to acknowledge Michelle Osterman at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for her assistance with analyzing the US Natality data set.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aldous MB, Edmonson MB. Maternal age at first childbirth and risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery in Washington State. Jama. 1993;270(21):2574–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobsson B, Ladfors L, Milsom I. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004;104(4):727–33. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000140682.63746.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleary-Goldman J, Malone FD, Vidaver J, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, et al. Impact of maternal age on obstetric outcome. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):983–90. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158118.75532.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser AM, Brockert JE, Ward RH. Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes. The New England journal of medicine. 1995;332(17):1113–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen XK, Wen SW, Fleming N, Demissie K, Rhoads GG, Walker M. Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a large population based retrospective cohort study. International journal of epidemiology. 2007;36(2):368–73. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khashan AS, Baker PN, Kenny LC. Preterm birth and reduced birthweight in first and second teenage pregnancies: a register-based cohort study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2010;10:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner MO, Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Tucker JM, Nelson KG, Copper RL. The origin and outcome of preterm twin pregnancies. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1995;85(4):553–7. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00455-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell RB, Petrini JR, Damus K, Mattison DR, Schwarz RH. The changing epidemiology of multiple births in the United States. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;101(1):129–35. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bortolus R, Parazzini F, Chatenoud L, Benzi G, Bianchi MM, Marini A. The epidemiology of multiple births. Human reproduction update. 1999;5(2):179–87. doi: 10.1093/humupd/5.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ. Three decades of twin births in the United States, 1980–2009. NCHS data brief. 2012;(80):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleicher N, Barad D. Twin pregnancy, contrary to consensus, is a desirable outcome in infertility. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2426–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong X, Dickey RP, Pridjian G, Buekens P. Maternal age and preterm births in singleton and twin pregnancies conceived by in vitro fertilisation in the United States. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2015;29(1):22–30. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misra DP, Ananth CV. Infant mortality among singletons and twins in the United States during 2 decades: effects of maternal age. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6):1163–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox NS, Rebarber A, Dunham SM, Saltzman DH. Outcomes of multiple gestations with advanced maternal age. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. 2009;22(7):593–6. doi: 10.1080/14767050902801819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki S. Obstetric outcomes in nulliparous women aged 35 and over with dichorionic twin pregnancy. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2007;276(6):573–5. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prapas N, Kalogiannidis I, Prapas I, Xiromeritis P, Karagiannidis A, Makedos G. Twin gestation in older women: antepartum, intrapartum complications, and perinatal outcomes. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2006;273(5):293–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-005-0089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristensen S, Salihu HM, Keith LG, Kirby RS, Pass MA, Fowler KB. Impact of advanced maternal age on neonatal survival of twin small-for-gestational-age subtypes. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2007;33(3):259–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blickstein I, Goldman RD, Mazkereth R. Incidence and birth weight characteristics of twins born to mothers aged 40 years or more compared with 35–39 years old mothers: a population study. Journal of perinatal medicine. 2001;29(2):128–32. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2001.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delbaere I, Verstraelen H, Goetgeluk S, Martens G, Derom C, De Bacquer D, et al. Perinatal outcome of twin pregnancies in women of advanced age. Human reproduction. 2008;23(9):2145–50. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salihu HM, Aliyu MH, Sedjro JE, Nabukera S, Oluwatade OJ, Alexander GR. Teen twin pregnancies: differences in fetal growth outcomes among blacks and whites. American journal of perinatology. 2005;22(6):335–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osterman MJ, Martin JA, Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Expanded data from the new birth certificate, 2008. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2011;59(7):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooperstock MS, Bakewell J, Herman A, Schramm WF. Association of sociodemographic variables with risk for very preterm birth in twins. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(1):53–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin JA, Wilson EC, Osterman MJ, Saadi EW, Sutton SR, Hamilton BE. Assessing the quality of medical and health data from the 2003 birth certificate revision: results from two states. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2013;62(2):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin JA, Osterman MJ, Kirmeyer SE, Gregory EC. Measuring Gestational Age in Vital Statistics Data: Transitioning to the Obstetric Estimate. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2015;64(5):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8(5):551–61. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010;29(9):1037–57. doi: 10.1002/sim.3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newburn-Cook CV, Onyskiw JE. Is older maternal age a risk factor for preterm birth and fetal growth restriction? A systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(9):852–75. doi: 10.1080/07399330500230912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Every newborn, every mother, every adolescent girl. Lancet. 2014;383(9919):755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2015;64(1):1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boulet SL, Shin M, Kirby RS, Goodman D, Correa A. Sensitivity of birth certificate reports of birth defects in Atlanta, 1995–2005: effects of maternal, infant, and hospital characteristics. Public health reports. 2011;126(2):186–94. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Wright C. Congenital anomalies in twins: a register-based study. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(6):1306–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]