Abstract

Background

It remains unclear whether severe exacerbation and pneumonia of COPD differs between patients treated with budesonide/formoterol and those treated with fluticasone/salmeterol. Therefore, we conducted a comparative study of those who used budesonide/formoterol and those treated with fluticasone/salmeterol for COPD.

Methods

Subjects in this population-based cohort study comprised patients with COPD who were treated with a fixed combination of budesonide/formoterol or fluticasone/salmeterol. All patients were recruited from the Taiwan National Health Insurance database. The outcomes including severe exacerbations, pneumonia, and pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation (MV) were measured.

Results

During the study period, 11,519 COPD patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol and 7,437 patients receiving budesonide/formoterol were enrolled in the study. Pairwise matching (1:1) of fluticasone/salmeterol and budesonide/formoterol populations resulted in to two similar subgroups comprising each 7,295 patients. Patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol had higher annual rate and higher risk of severe exacerbation than patients receiving budesonide/formoterol (1.2219/year vs 1.1237/year, adjusted rate ratio, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.07–1.10). In addition, patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol had higher incidence rate and higher risk of pneumonia than patients receiving budesonide/formoterol (12.11 per 100 person-years vs 10.65 per 100 person-years, adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.13; 95% CI, 1.08–1.20). Finally, patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol had higher incidence rate and higher risk of pneumonia requiring MV than patients receiving budesonide/formoterol (3.94 per 100 person-years vs 3.47 per 100 person-years, aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05–1.24). A similar trend was seen before and after propensity score matching analysis, intention-to-treat, and as-treated analysis with and without competing risk.

Conclusions

Based on this retrospective observational study, long-term treatment with fixed combination budesonide/formoterol was associated with fewer severe exacerbations, pneumonia, and pneumonia requiring MV than fluticasone/salmeterol in COPD patients.

Keywords: COPD, ICS/LABA, exacerbation, pneumonia

Introduction

COPD is characterized by progressive and persistent airflow limitation.1 The disease is a major cause of chronic morbidity and is estimated to be the third leading cause of death worldwide by 2020.2–4 Exacerbation of COPD is a significant contributor to mortality, especially in patients who require hospitalization.5–8 Several studies9–13 have demonstrated that a fixed-dose combination of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) can effectively reduce the risk of COPD exacerbation. In Taiwan, there are two fixed-dose combinations of inhaled LABA and ICS available as treatment for COPD, namely budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort Turbuhaler, AztraZeneca) and fluticasone/salmeterol (Seretide Accuhaler and Seretide Evohaler, GlaxoSmithKline). Both combinations have been shown to result in fewer exacerbation episodes and to improve quality of life.9–13 However, it remains unclear whether the two combinations are equally effective at reducing the frequency of exacerbations.

Previously, our study and other studies all showed that ICSs are significantly associated with an increased risk of pneumonia in COPD patients.13,14 Findings from the PATHOS study revealed that budesonide/formoterol is more effective than fluticasone/salmeterol in preventing exacerbations and pneumonia in patients with moderate and severe COPD.13,15 However, most of the patients in that study were of Scandinavian origin, making it difficult to generalize their findings to Asian populations, such as Taiwanese.

The Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) consists of standard computerized claims documents submitted by medical institutions seeking reimbursement through the National Health Insurance (NHI) program. The NHI program provides the medical needs for more than 23 million people, representing >98% of the population in Taiwan, and records clinical diagnoses according to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. In this population-based study, we compared the effects of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol on the occurrence of severe exacerbation and pneumonia in propensity score-matched COPD patients with long-term follow-up sourced from the Taiwan NHIRD.

Methods

Data source

This study used a subset of the NHIRD comprising information on 2,200,000 individuals with COPD, representing 60.5% of all patients with heart or lung disease in the NHI database (n=3,635,539). This cohort was followed longitudinally from 1997 to 2010. The records of patients retrieved from the NHIRD were anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis. Therefore, no informed consent was required and it was specifically waived by the Institutional Review Board. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of NHRI.

Selection of patients with COPD

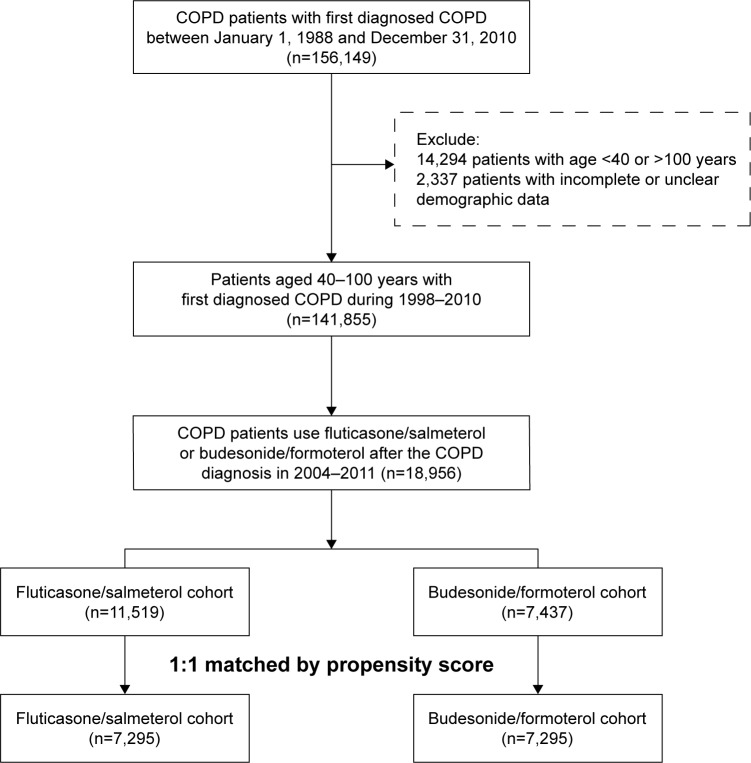

Adult patients with COPD ≥40 and ≤100 years were identified using ICD-9-CM codes 491, 492, and 496. Inclusion criteria included a record of at least three outpatient or one inpatient visits for COPD and ever undergone a lung function test within 1 year before and after the diagnosis of COPD had been established. Thus, a total of 141,855 patients were identified as having COPD. Of those patients, only 18,956 patients received a fixed ICS and LABA combination (budesonide/formoterol Turbuhaler or fluticasone/salmeterol Accuhaler or Metered Dose Inhaler) (Figure 1). The index date was defined as the date of the first fixed ICS/LABA combination prescription after COPD had been diagnosed. Patients were followed until 31 December 2010, or the end of treatment with a fixed combination, emigration or death.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study cohort selection.

Outcome measurements

Severe exacerbation was defined as COPD-related hospitalizations or emergency department visits. Pneumonia was defined as COPD patients who developed pneumonia requiring emergency department or hospital admission. Pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation (MV) was defined as COPD patients with pneumonia and using MV for respiratory failure.

Exposure measures and potential confounders

Fixed ICS/LABA combinations were defined as Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes R03AK06 or R03AK07 as previous report.14 COPD exacerbation events were calculated only during the same fixed ICS/LABA combination usage period. If the patient changed to the other fixed ICS/LABA combination, the patient was censored. In order to control for potential confounding factors, data regarding the use of ICSs (ATC code R03BA), LABAs (ATC codes R03AC12 and R03AC13), short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs; ATC code R03AC), and other related drugs were assessed.

Statistical analysis

We used pairwise 1:1 propensity score matching (greedy 5-to-1 digit matching without replacement) and logistic regression to reduce concerns related to nonrandom assignment of patients to treatments.16 The propensity score method is used to reduce potential confounding caused by unbalanced covariates. The matching starts with the smallest population (7,437 patients in the budesonide/formoterol group) and matches them 1:1 to the larger treatment group. Patients treated with either treatment combination were matched on the following criteria: age, sex, number of prescriptions for antibiotics, oral steroids, ICS, long-acting and short-acting bronchodilators, diagnosis of diabetes, cancer, heart failure, hypertension, stroke, and the number of previous severe COPD exacerbations – COPD-related hospitalizations or emergency department visits.

Intention-to-treat analyses were used as the primary analyses for this study because of more reliable estimates of comparative treatment effectiveness in real-world applications. Both cohorts were followed, until the study outcome, according to original treatment allocation, regardless of adherence to or subsequent withdrawal or deviation from the inclusion criteria. In the as-treated analyses, the person-time in the as-treated population, a subset of all person-time in the intention-to-treat analyses, was censored on the day of medication add-on, switching, or discontinuation. Cox regression models were used to calculate the crude and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) of different outcomes including mortality, pneumonia, and pneumonia requiring MV between the two study cohorts. Adjusted HRs and 95% CIs were calculated by using Cox regression models adjusted for propensity scores (continuous).

The annual severe exacerbation event rate (emergency department visits or admissions to hospital) observed with each ICS/LABA regimen was compared between the groups using Poisson regression, with events as the dependent variable and time on specific fixed combination treatment as an offset variable. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance in all analyses. The software packages used for data analysis included SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, 18,956 patients received a fixed ICS/LABA combination (11,519 patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol and 7,437 patients receiving budesonide/formoterol). Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of these two groups. Before propensity score matching, patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol were older and more male patients received budesonide/formoterol. Patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol had more frequent severe acute exacerbations, and less use of COPD inhaled and oral drugs except long-acting muscarinic antagonist than patients receiving budesonide/formoterol. Pairwise matching (1:1) of fluticasone/salmeterol and budesonide/formoterol populations resulted in two similar subgroups each comprising 7,295 patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of COPD patients prescribed fluticasone/salmeterol and budesonide/formoterol before and after matching by propensity score matching

| Variables | Before propensity score matching

|

After propensity score matching

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluticasone/salmeterol | Budesonide/formoterol | P-value | Fluticasone/salmeterol | Budesonide/formoterol | P-value | |||||

| Patient (n) | 11,519 | 7,437 | 7,295 | 7,295 | ||||||

| Age (year) | 65.95±10.26 | 63.28±10.40 | <0.0001 | 63.66±10.33 | 63.53±10.30 | 0.4334 | ||||

| Male gender | 8,801 | 76.40% | 5,434 | 76.14% | <0.0001 | 5,386 | 73.83% | 5,360 | 73.47% | 0.6251 |

| Index year | ||||||||||

| 2004 | 1,963 | 17.04% | 1,430 | 20.04% | <0.0001 | 1,439 | 19.73% | 1,408 | 19.30% | 0.9301 |

| 2005 | 1,261 | 10.95% | 1,231 | 17.25% | 1,102 | 15.11% | 1,146 | 15.71% | ||

| 2006 | 1,326 | 11.51% | 990 | 13.87% | 987 | 13.53% | 972 | 13.32% | ||

| 2007 | 1,486 | 12.90% | 973 | 13.63% | 991 | 13.58% | 967 | 13.26% | ||

| 2008 | 1,375 | 11.94% | 843 | 11.81% | 841 | 11.53% | 833 | 11.42% | ||

| 2009 | 1,543 | 13.40% | 762 | 10.68% | 746 | 10.23% | 762 | 10.45% | ||

| 2010 | 1,571 | 13.64% | 815 | 11.42% | 818 | 11.21% | 814 | 11.16% | ||

| 2011 | 994 | 8.63% | 393 | 5.51% | 371 | 5.09% | 393 | 5.39% | ||

| Monthly income, n (%) | ||||||||||

| <19,100 | 4,040 | 35.07% | 2,481 | 34.76% | 0.0006 | 2,429 | 33.30% | 2,455 | 33.65% | 0.8927 |

| 19,100–41,999 | 6,012 | 52.19% | 3,874 | 54.28% | 3,831 | 52.52% | 3,805 | 52.16% | ||

| ≥42,000 | 1,467 | 12.74% | 1,082 | 15.16% | 1,035 | 14.19% | 1,035 | 14.19% | ||

| Hospital level, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Level 1 | 4,651 | 40.38% | 3,077 | 43.11% | <0.0001 | 2,944 | 40.36% | 3,004 | 41.18% | 0.7384 |

| Level 2 | 4,887 | 42.43% | 2,907 | 40.73% | 2,920 | 40.03% | 2,880 | 39.48% | ||

| Level 3 | 1,477 | 12.82% | 1,016 | 14.24% | 1,016 | 13.93% | 990 | 13.57% | ||

| Level 4 (rural area) | 504 | 4.38% | 437 | 6.12% | 415 | 5.69% | 421 | 5.77% | ||

| COPD severe AE | ||||||||||

| 0 | 6,340 | 55.04% | 4,580 | 64.17% | <0.0001 | 4,443 | 60.90% | 4,457 | 61.10% | 0.7490 |

| 1 | 1,915 | 16.62% | 1,102 | 15.44% | 1,122 | 15.38% | 1,090 | 14.94% | ||

| ≥2 | 3,264 | 28.34% | 1,755 | 24.59% | 1,730 | 23.71% | 1,748 | 23.96% | ||

| Medication for COPD | ||||||||||

| LABA | 412 | 3.58% | 366 | 5.13% | <0.0001 | 338 | 4.63% | 347 | 4.76% | 0.7247 |

| SABA | 3,400 | 29.52% | 2,514 | 35.22% | <0.0001 | 2,396 | 32.84% | 2,426 | 33.26% | 0.5975 |

| LAMA | 1,488 | 12.92% | 711 | 9.96% | <0.0001 | 694 | 9.51% | 708 | 9.71% | 0.6941 |

| ICS | 3,155 | 27.39% | 2,591 | 36.30% | <0.0001 | 2,459 | 33.71% | 2,478 | 33.97% | 0.7396 |

| Medication for hypertension | ||||||||||

| Alpha-blocker | 1,258 | 10.92% | 782 | 10.96% | 0.3784 | 802 | 10.99% | 774 | 10.61% | 0.4552 |

| Beta-blocker | 3,159 | 27.42% | 1,910 | 26.76% | 0.0082 | 1,902 | 26.07% | 1,889 | 25.89% | 0.8061 |

| Calcium-channel Blocker | 5,579 | 48.43% | 3,358 | 47.05% | <0.0001 | 3,306 | 45.32% | 3,315 | 45.44% | 0.8810 |

| Diuretic | 4,359 | 37.84% | 2,450 | 34.33% | <0.0001 | 2,413 | 33.08% | 2,432 | 33.34% | 0.7384 |

| ACEI or ARB | 4,139 | 35.93% | 2,492 | 34.92% | 0.0006 | 2,494 | 34.19% | 2,456 | 33.67% | 0.5064 |

| Other medication | ||||||||||

| Aspirin | 1,542 | 13.39% | 813 | 11.39% | <0.0001 | 782 | 10.72% | 807 | 11.06% | 0.5064 |

| Clopidogrel | 633 | 5.50% | 335 | 4.69% | 0.0025 | 321 | 4.40% | 331 | 4.54% | 0.6887 |

| Ticlopidine | 221 | 1.92% | 117 | 1.64% | 0.0794 | 120 | 1.64% | 116 | 1.59% | 0.7929 |

| Dipyridamole | 1,558 | 13.53% | 886 | 12.41% | 0.0012 | 889 | 12.19% | 881 | 12.08% | 0.8392 |

| Nitrate | 153 | 1.33% | 77 | 1.08% | 0.0721 | 74 | 1.01% | 76 | 1.04% | 0.8696 |

| Statin | 1,429 | 12.41% | 896 | 12.55% | 0.4635 | 867 | 11.88% | 883 | 12.10% | 0.6835 |

| NSAID | 8,791 | 76.32% | 5,748 | 80.54% | 0.1222 | 5,676 | 77.81% | 5,636 | 77.26% | 0.4275 |

| Anti-hyperglycemic drugs | 1,857 | 16.12% | 1,019 | 14.28% | <0.0001 | 1,015 | 13.91% | 1,011 | 13.86% | 0.9237 |

| Proton-pump inhibitor | 1,371 | 11.90% | 804 | 11.27% | 0.0213 | 781 | 10.71% | 793 | 10.87% | 0.7488 |

| Baseline comorbidities | ||||||||||

| Charlson score (mean ± SD) | 1.64±1.00 | 1.55±0.90 | <0.0001 | 1.55±0.90 | 1.55±0.90 | 0.5337 | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 190 | 1.65% | 95 | 1.33% | 0.0398 | 86 | 1.18% | 94 | 1.29% | 0.5485 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1,030 | 8.94% | 584 | 8.18% | 0.0087 | 567 | 7.77% | 584 | 8.01% | 0.6016 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 92 | 0.80% | 52 | 0.73% | 0.4412 | 53 | 0.73% | 52 | 0.71% | 0.9220 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 578 | 5.02% | 279 | 3.91% | <0.0001 | 255 | 3.50% | 276 | 3.78% | 0.3532 |

| Dementia | 194 | 1.68% | 67 | 0.94% | <0.0001 | 65 | 0.89% | 67 | 0.92% | 0.8612 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 114 | 0.99% | 74 | 1.04% | 0.9710 | 71 | 0.97% | 70 | 0.96% | 0.9326 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1,703 | 14.78% | 1,052 | 14.74% | 0.2231 | 1,018 | 13.95% | 1,032 | 14.15% | 0.7387 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 7 | 0.06% | 2 | 0.03% | 0.2958 | 2 | 0.03% | 2 | 0.03% | 1.0000 |

| Renal disease | 271 | 2.35% | 153 | 2.14% | 0.1794 | 148 | 2.03% | 152 | 2.08% | 0.8155 |

| Moderate/severe liver disease | 1,255 | 10.90% | 706 | 9.89% | 0.0020 | 675 | 9.25% | 701 | 9.61% | 0.4614 |

| Cancer | 375 | 3.26% | 239 | 3.35% | 0.8738 | 241 | 3.30% | 234 | 3.21% | 0.7440 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 372 | 3.23% | 202 | 2.83% | 0.0440 | 205 | 2.81% | 199 | 2.73% | 0.7621 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor; AE, acute exacerbation; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long acting beta agonists; LAMA, long acting antimuscarinics; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SABA, short acting beta agonists.

Effect on severe exacerbation

Following matching, the post-index all severe exacerbation rates were 1.2219 and 1.1237 per patient-year in the fluticasone/salmeterol and budesonide/formoterol groups, respectively (adjusted rate ratio 1.08, 95% CI, 1.07–1.10) (Table 2). Patients treated with fluticasone/salmeterol had significantly higher rates of hospitalization (rate ratio 1.11, 95% CI, 1.08–1.13) or emergency department visits (rate ratio 1.09, 95% CI, 1.07–1.11) for COPD (Table 2). The results before matching were the same as following matching.

Table 2.

Yearly rates and rate ratios of severe exacerbation, hospitalization for COPD, and emergency department visits for COPD exacerbation in a matched cohort of COPD patients prescribed fluticasone/salmeterol and budesonide/formoterol

| Fluticasone/salmeterol cohort

|

Budesonide/formoterol cohort

|

Crude RR | (95% CI) | Adjusted RR* | (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yearly rate | Yearly rate | |||||

| Before propensity score matching | ||||||

| Severe exacerbation | 1.3368 | 1.1096 | 1.05 | (1.04–1.07) | 1.06 | (1.04–1.07) |

| Hospitalization for COPD | 0.6271 | 0.4827 | 1.14 | (1.11–1.16) | 1.10 | (1.07–1.12) |

| Emergency department visits for COPD | 1.0380 | 0.8601 | 1.06 | (1.04–1.07) | 1.07 | (1.05–1.08) |

| After propensity score matching | ||||||

| Severe exacerbation | 1.2219 | 1.1237 | 1.08 | (1.07–1.10) | 1.08 | (1.07–1.10) |

| Hospitalization for COPD | 0.5455 | 0.4915 | 1.11 | (1.08–1.13) | 1.11 | (1.08–1.13) |

| Emergency department visits for COPD | 0.9528 | 0.8688 | 1.09 | (1.07–1.11) | 1.09 | (1.07–1.11) |

Note:

Adjusted for propensity score.

Abbreviation: RR, rate ratio.

Effect on pneumonia and pneumonia requiring MV

Patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol had higher incidence rate and higher risk of pneumonia than patients receiving budesonide/formoterol (12.11 per 100 person-years vs 10.65 per 100 person-years, aHR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.08–1.20) (Table 3). In addition, patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol had higher incidence rate and higher risk of pneumonia requiring MV than patients receiving budesonide/formoterol (3.94 per 100 person-years vs 3.47 per 100 person-years, aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05–1.24; Table 3). Finally, patients receiving fluticasone/salmeterol had higher incidence rate and higher risk of mortality than patients receiving budesonide/formoterol (4.89 vs 4.50, aHR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01–1.17; Table 3). Similar results were obtained for both cohorts before propensity score matching.

Table 3.

Event rates and risks of pneumonia, pneumonia requiring MV in a matched cohort of COPD patients prescribed fluticasone/salmeterol and budesonide/formoterol

| Fluticasone/salmeterol cohort

|

Budesonide/formoterol cohort

|

Crude HR (95% CI) |

Adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Person-year | Incidence rate (per 100 person-years) | Event | Person-year | Incidence rate (per 100 person-years) | |||

| Before propensity score matching | ||||||||

| Mortality | 2,438 | 41,741.61 | 5.84 | 1,359 | 30,807.16 | 4.41 | 1.32 (1.24–1.41) | 1.09 (1.01–1.17) |

| Pneumonia | 4,610 | 32,150.0 | 14.34 | 2,610 | 24,829.2 | 10.51 | 1.31 (1.25–1.38) | 1.13 (1.08–1.20) |

| Pneumonia requiring MV | 1,895 | 39,367.10 | 4.81 | 1,004 | 29,496.66 | 3.40 | 1.39 (1.28–1.50) | 1.13 (1.04–1.24) |

| After propensity score matching | ||||||||

| Mortality | 1,461 | 29,857.98 | 4.89 | 1,349 | 29,955.79 | 4.50 | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | 1.09 (1.01–1.17) |

| Pneumonia | 2,839 | 23,448.09 | 12.11 | 2,569 | 24,124.61 | 10.65 | 1.12 (1.06–1.17) | 1.13 (1.08–1.20) |

| Pneumonia requiring MV | 1,118 | 28,373.96 | 3.94 | 996 | 28,671.31 | 3.47 | 1.16 (1.07–1.25) | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) |

Note:

Adjusted for propensity score.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; MV, mechanical ventilation.

We obtained similar results in the sensitivity analyses (Table 4). In the as-treated analyses, we found the group of fluticasone/salmeterol had higher risk of pneumonia and pneumonia requiring MV. When death was treated as a competing risk, the risks of pneumonia and pneumonia requiring MV still remained lower in budesonide/formoterol group.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses for risk of pneumonia and pneumonia requiring MV among COPD patients using fluticasone/salmeterol and budesonide/formoterol

| Before propensity score matching

|

After propensity score matching

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude

|

Adjusted*

|

Crude

|

Adjusted*

|

|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Primary analysis | ||||

| Mortality | 1.32 (1.24–1.41) | 1.09 (1.01–1.17) | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | 1.09 (1.01–1.17) |

| Pneumonia | 1.31 (1.25–1.38) | 1.13 (1.08–1.20) | 1.12 (1.06–1.17) | 1.13 (1.08–1.20) |

| Pneumonia requiring MV | 1.39 (1.28–1.50) | 1.13 (1.04–1.24) | 1.16 (1.07–1.25) | 1.14 (1.05–1.24) |

| ITT analysis + competing risk | ||||

| Mortality | – | – | – | – |

| Pneumonia | 1.24 (1.17–1.30) | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) |

| Pneumonia requiring MV | 1.27 (1.17–1.38) | 1.09 (1.01–1.18) | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) |

| As-treated analysis | ||||

| Mortality | 1.54 (1.39–1.70) | 1.23 (1.09–1.37) | 1.25 (1.12–1.38) | 1.21 (1.08–1.35) |

| Pneumonia | 1.44 (1.34–1.54) | 1.17 (1.08–1.26) | 1.17 (1.09–1.25) | 1.17 (1.08–1.26) |

| Pneumonia requiring MV | 1.70 (1.51–1.91) | 1.32 (1.16–1.51) | 1.34 (1.19–1.52) | 1.32 (1.15–1.51) |

| As-treated analysis + competing risk | ||||

| Mortality | – | – | – | – |

| Pneumonia | 1.32 (1.22–1.42) | 1.11 (1.03–1.20) | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) |

| Pneumonia requiring MV | 1.48 (1.30–1.68) | 1.20 (1.06–1.37) | 1.21 (1.05–1.40) | 1.21 (1.05–1.39) |

Note:

Adjusted for propensity score.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; MV, mechanical ventilation; ITT, intention-to-treat.

Discussion

This national population-based study compromising two matched cohorts each comprising 7,295 COPD patients treated with either fluticasone/salmeterol or budesonide/formoterol has several significant findings. Most important of all, we found that the budesonide/formoterol group had fewer episodes of severe exacerbations than the fluticasone/salmeterol group. Moreover, patients treated with budesonide/formoterol had a significantly lower rate of hospitalization or emergency department visit for COPD exacerbation. In addition, the episodes of pneumonia and pneumonia requiring MV were significantly higher in the fluticasone/salmeterol group than in the budesonide/formoterol group. Our findings indicate that fixed combination budesonide/formoterol is more effective in preventing severe exacerbation of COPD and pneumonia than fluticasone/salmeterol.

One of the strengths of the present study is that it is a nationwide population-based cross-sectional study that includes almost all patients with COPD in Taiwan. In fact, the NHI program covers 99.0% of Taiwan’s population and the NHRID contains near complete follow-up information for the whole study population. In addition, the database is routinely monitored for diagnostic accuracy by the National Health Insurance Bureau. The diagnosis of COPD in most patients was made by physicians based on clinical findings without pulmonary function test results. To improve the accuracy of the COPD diagnosis, only patients who had received pulmonary function tests within 1 year of receiving a diagnosis of COPD were enrolled. In this study, we also used propensity score matching to minimize the effects of possible confounding variables. Therefore, our study should be representative of the status of patients with COPD in Taiwan who are treated with fixed ICS/LABA combinations. Besides we also performed sensitivity analyses and calculated competing risk with mortality.

Blais et al conducted a 1-year, population-based, matched cohort study of 2,262 patients using data sourced from administrative health care databases from the Canadian province of Quebec and found no significant differences in frequency of COPD exacerbations between patients treated with fluticasone/salmeterol and those who received budesonide/formoterol (0.71 vs 0.63 exacerbation/patient-year).17 Although the rate of COPD exacerbations in the year after the index date was lower in the budesonide/formoterol group than in the fluticasone/salmeterol group after adjustment for confounding factors (adjusted risk ratio. 0.88, 95% CI, 0.76–1.00), the difference did not reach statistical significance.17 In contrast, the PATHOS study in Sweden, which enrolled two cohorts of 2,738 patients each, comprising more than 19,000 patient-years, who were followed for up to 11 years, found that budesonide/formoterol was significantly associated with fewer exacerbations than fluticasone/salmeterol in the first year and that the difference between the two combinations increased with study duration.15 The discrepancy in findings between the population-based study performed in Canada and that in Sweden may be due to differences in sample size or study duration. In our study, which included more than 30,000 patients and a longer follow-up period than in the PATHOS study or the study by Blais et al, the findings were similar to those reported in the PATHOS study.15 Finally, consistent with previous studies in western countries,15,17 we found budesonide/formoterol was associated with significantly lower rates of emergency department visits and hospitalization due to COPD than fluticasone/salmeterol. The above-mentioned findings suggest that fixed combination budesonide/formoterol more effectively prevents exacerbation of COPD than fluticasone/salmeterol in Caucasian as well as Asian populations.

Several factors may help to explain the differences in effectiveness between budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol. For example, studies have shown that budesonide/formoterol results in a more rapid onset of bronchodilation and offers faster symptom control than fluticasone/salmeterol.18,19 Better symptom control may contribute to the lower rate of emergency department visits or hospitalizations in the long term.17 The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of the two combinations may also explain, at least in part, the differences in effectiveness between fluticasone and budesonide. Several studies have demonstrated that fluticasone is a more lipophilic corticosteroid than budesonide, allowing for its longer retention in the airway, and that it is a more potent immunosuppressant, thereby facilitating bacterial colonization and infection-associated exacerbations.19–23

There are several limitations in this study. First, we did not have detailed data on pulmonary function test results or quality of life assessment. Therefore, we could not evaluate the severity of COPD or determine whether every patient received an ICS/LABA combination according to the recommended guidelines.1 Second, despite our use of propensity score matching, it is still possible that residual confounding factors, such as duration of COPD, smoking habit, the result of pulmonary function test or prior number of COPD exacerbation without hospitalizations were not taken into account in the analysis. Third, this study was not a randomized controlled study. Nonetheless, our findings are derived from the real world’s situation, and are more likely to be reflective of common clinical practice.

Conclusion

In our retrospective comparative study of ICS/LABA medication utilization for COPD, long-term treatment with the fixed combination of budesonide/formoterol was associated with fewer health care utilization-defined exacerbations than fluticasone/salmeterol in patients with moderate and severe COPD.

Acknowledgments

Taiwan Clinical Trial Consortium for Respiratory Diseases (TCORE) includes: Chong-Jen Yu, MD, PhD (NTUH, Director of Coordinating Center and Core PI of Committee), Hao-Chien Wang, MD, PhD (NTUH, PI of Committee), Diahn-Warng Perng, MD, PhD (Taipei Veterans General Hospital, PI of Committee), Shih-Lung Cheng, MD, PhD (Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, PI of Committee), Jeng-Yuan Hsu, MD, PhD (Taichung Veterans General Hospital, PI of Committee), Wu-Huei Hsu, MD, PhD (China Medical University Hospital, PI of Committee), Ying-Huang Tsai, MD, PhD (Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chia-Yi, PI of Committee), Tzuen-Ren Hsiue, MD, PhD (National Cheng Kung University Hospital, PI of Committee), Meng-Chih Lin, MD, PhD (Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung, PI of Committee), Hen-I Lin, MD (Cardinal Tien Hospital, PI of Committee), Cheng-Yi Wang, MD, PhD (Cardinal Tien Hospital, PI of Committee), Yeun-Chung Chang, MD, PhD (NTUH, PI of Committee), Ueng-Cheng Yang, PhD (National Yang-Ming University, PI of Committee), Chung-Ming Chen, PhD (NTUH, PI of Committee), Cing-Syong Lin, MD, PhD (Changhua Christian Hospital, PI of Committee), Likwang Chen, PhD (National Health Research Institutes, PI of Committee), Yu-Feng Wei, MD (E-Da Hospital, PI of Committee), Inn-Wen Chong, MD (Kaohsiung Medical University Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital, PI of Committee), Chung-Yu Chen (NTUH, Yun-Lin, PI of Committee). This study was supported by grants from National Science Council (NSC 101-2325-B-002-064, NSC 102-2325-B-002-087, NSC 103-2325-B-002-027, NSC 104-2325-B-002-035, and NSC-105-2325-B-002-030) and from National Health Research Institutes (intramural funding).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases . Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Vancouver, WA: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Accessed July 1, 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/statistics.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of diseases from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax. 2012;67(11):957–963. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Melo MN, Ernst P, Suissa S. Inhaled corticosteroids and the risk of a first exacerbation in COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(5):692–697. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00049604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourbeau J, Ernst P, Cockcoft D, Suissa S. Inhaled corticosteroids and hospitalisation due to exacerbation of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(2):286–289. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00113802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suissa S. Number needed to treat in COPD: exacerbations versus pneumonias. Thorax. 2013;68(6):540–543. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Melo MN, Ernst P, Suissa S. Rates and patterns of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Can Respir J. 2004;11(8):559–564. doi: 10.1155/2004/813058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J, et al. TRial of Inhaled STeroids ANd long-acting beta2 agonists study group Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9356):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. TORCH investigators Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):775–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calverley PM, Boonsawat W, Cseke Z, et al. Maintenance therapy with budesonide and formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(6):912–919. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00027003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szafranski W, Cukier A, Ramirez A, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(1):74–81. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00031402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janson C, Larsson K, Lisspers KH, et al. Pneumonia and pneumonia related mortality in patients with COPD treated with fixed combinations of inhaled corticosteroid and long acting β2 agonist: observational matched cohort study (PATHOS) BMJ. 2013;346:f3306. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang CY, Lai CC, Yang WC, et al. The association between inhaled corticosteroid and pneumonia in COPD patients: the improvement of patients’ life quality with COPD in Taiwan (IMPACT) study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2775–2783. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S116750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsson K, Janson C, Lisspers K, et al. Combination of budesonide/formoterol more effective than fluticasone/salmeterol in preventing exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the PATHOS study. J Intern Med. 2013;273(6):584–594. doi: 10.1111/joim.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Exploring the nature of covariate effects in the proportional hazards model. Biometrics. 1990;46(4):1005–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blais L, Forget A, Ramachandran S. Relative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in a 1-year, population-based, matched cohort study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Effect on COPD-related exacerbations, emergency department visits and hospitalizations, medication utilization, and treatment adherence. Clin Ther. 2010;32(7):1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tashkin DP, Rennard SI, Martin P, et al. Efficacy and safety of budesonide and formoterol in one pressurized metered-dose inhaler in patients with moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results of a 6-month randomized clinical trial. Drugs. 2008;68(14):1975–2000. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rennard SI, Tashkin DP, McElhattan J, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of budesonide/formoterol in one hydrofluoroalkane pressurized metered-dose inhaler in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from a 1-year randomized controlled clinical trial. Drugs. 2009;69(5):549–565. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969050-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorsson L, Edsbäcker S, Källén A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and systemic activity of fluticasone via Diskus and pMDI, and of budesonide via Turbuhaler. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52(5):529–538. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalby C, Polanowski T, Larsson T, et al. The bioavailability and airway clearance of the steroid component of budesonide/formoterol and salmeterol/fluticasone after inhaled administration in patients with COPD and healthy subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Respir Res. 2009;10:104. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brattsand R, Miller-Larsson A. The role of intracellular esterification in budesonide once-daily dosing and airway selectivity. Clin Ther. 2003;25(Suppl C):C28–C41. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ek A, Larsson K, Siljerud S, et al. Fluticasone and budesonide inhibit cytokine release in human lung epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages. Allergy. 1999;54(7):691–699. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]