Abstract

The PEND protein is a DNA-binding protein in the inner envelope membrane of a developing chloroplast, which may anchor chloroplast nucleoids. Here we report the DNA-binding characteristics of the N-terminal basic region plus leucine zipper (bZIP)-like domain of the PEND protein that we call cbZIP domain. The basic region of the cbZIP domain diverges significantly from the basic region of known bZIP proteins that contain a bipartite nuclear localization signal. However, the cbZIP domain has the ability to dimerize in vitro. Selection of binding sites from a random sequence pool indicated that the cbZIP domain preferentially binds to a canonical sequence, TAAGAAGT. The binding site was also confirmed by gel mobility shift analysis using a representative binding site within the chloroplast DNA. These results suggest that the cbZIP domain is a unique DNA-binding domain of the chloroplast protein.

INTRODUCTION

In a previous study (1), we isolated a cDNA (PD2) for a DNA-binding protein from pea. The PD2 cDNA encodes a 70 kDa polypeptide, which was identified as a subunit of the PEND protein, a 130 kDa DNA binding protein in the inner envelope membrane of developing chloroplast (2). The chloroplast nucleoid is a complex of chloroplast DNA and various, mostly unknown DNA-binding proteins, and is known to change its morphology, size and localization within the chloroplast during the development of the leaf (3–6). In developing leaf cells, a large number of nucleoids are attached to the chloroplast envelope membrane during their replication. The PEND protein was identified as a candidate that plays a role in the binding of nucleoids to the envelope membrane during the replication of nucleoids (1,2). Various lines of evidence suggest that the endogenous 130 kDa PEND protein is likely to be a homodimer of 70 kDa PD2 polypeptides (or ‘PEND polypeptides’) (1). However, the PEND protein is a very strange membrane-bound protein that is hard to handle with common techniques, and we are trying to characterize this protein from various viewpoints, such as the localization and orientation within the chloroplast, the signal for targeting to the chloroplast, the molecular structure of the endogenous protein, etc.

The DNA-binding domain of the PEND polypeptide was located at the N-terminus of the mature protein. It consists of a region enriched in basic amino acid residues and a potential zipper region containing a heptad repeat of bulky hydrophobic residues. These characteristics were thought to be similar to those of the basic region plus leucine zipper (bZIP) proteins, one of the major groups of nuclear transcription factors. Essential features of the bZIP domains are dimerization through the zipper region and binding of the basic region to DNA (7,8). All bZIP proteins known to date are localized in the cell nucleus and function as transcription factors (7,9,10). A bipartite nuclear localization signal has been identified within the basic region of bZIP domains (asterisks in Fig. 1). However, a close examination of the DNA-binding domain of the PEND polypeptide indicates that this domain might be different from the bZIP domains. First, the PEND protein is localized to the chloroplast. Secondly, the basic region of the PEND polypeptide is not similar to the basic region of the bZIP domains. Nevertheless, we thought that the DNA-binding domain of the PEND polypeptide might act as a dimeric DNA-binding motif, as do bZIP domains, because of the presence of a basic region and a potential zipper region.

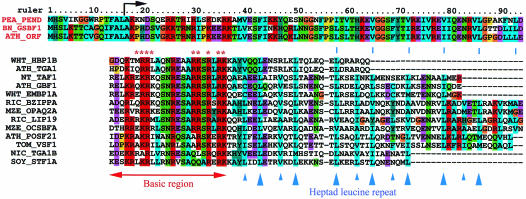

Figure 1.

Alignment of the cbZIP domains (upper sequences) with selected bZIP domains (lower sequences) of plant transcription factors. The bipartite nuclear localization signal of the bZIP domains is indicated by asterisks. The consensus residues are colored according to the default color table of the CLUSTAL X program. Complete N-terminal sequences of the PEND protein precursor and its homologs are shown with the location (arrow) of the N-terminus of purified pea PEND protein. Sources of sequences: pea (PEA), PEND (X98740); B.napus (BN), GSBF1 (X91138); A.thaliana (ATH), TGA1 (X68053), GBF1 (X63894), POSF21 (X61031), ORF (PEND homolog, AL049711 gene F4F15.280); wheat (WHT), HBP1B (X56782), EMBP1A (U07933); tobacco (NT), TAF1 (X60363); rice (RIC), BZIPPA (D78609), LIP19 (X57325); maize (MZE), OPAQ2A (M29411), OCSBFA (X62745); tomato (TOM), VSF1 (X73635); Nicotiana sp. (NIC), TGA1B (X16450); soy bean (SOY), STF1A (L28003).

The aim of the present study is to characterize the DNA-binding domain of the PEND polypeptide. Here we show evidence that the DNA-binding domain can dimerize and bind to a specific octamer sequence within the chloroplast DNA. We propose a name ‘cbZIP’ for this DNA-binding motif which contains a unique basic region and a zipper region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Alignment of the cbZIP and bZIP sequences and computer-assisted sequence analysis

Representative plant bZIP protein sequences that are listed in a paper by Vettore et al. (11) were retrieved from the GenBank database release 106. The bZIP domains were extracted and aligned by the CLUSTAL X program (12). Then, another alignment of cbZIP sequences of pea PEND, Brassica GSBF1 (13) and an Arabidopsis homolog (GenBank accession no. ATF4F15) were added to this alignment. Manipulation and analysis of sequences were done with the SISEQ program package (14). BLAST program (15) was used for homology search. These programs were run on workstations, Sun Ultra 10 (Solaris 2.6), Silicon Graphics O2 (Irix 6.5) and IBM Think Pad 600E (Linux kernel 2.2.14).

Preparation of PEND fusion proteins

The cbZIP region (abbreviated as BZ) and the coiled-coil (CC) region of the PEND cDNA (Fig. 2C) were amplified by the primer sets BZ1F/BZ1R and CC1F/CC1R, respectively: BZ1F, 5′-ATGGATCCGCAAAGAAAAATGATTCTCAAGAGAGAAAGACT (nucleotides 248–280 in the database X98740); BZ1R, 5′-ATGTCGACCAGTCTGTCATTCGTATCGGGAACTTTGTT (nucleotides 616–587); CC1F, 5′-ATGGATCCACTAGCAGTGGAAGAGAAGGTTCTGAAGA (nucleotides 1502–1530); CC1R, 5′-ATGTCGACTAAAGTAGAATTATCTGTGGGCTCTATGCCTT (nucleotides 1639–1608). The underlined parts are BamHI or SalI linkers. The amplified DNAs were digested with BamHI and SalI and then inserted into either pGEX-4T-2 (Amersham/Pharmacia) or pMAL-c2 (New England Biolabs). Preparation of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins (GST–BZ and GST–CC) with glutathione–Sepharose 4B (Amersham/Pharmacia) or the maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins (MBP–BZ and MBP–CC) with amylose resin (New England Biolabs) were performed according to the directions of the respective manufacturers, except that the crude extract was treated with DNase I to reduce contamination of nucleic acids. Another cbZIP–GST fusion protein (GST–BZ2) was prepared from the pGEX-PD2zip plasmid containing a PEND sequence from nucleotide 227 to 642, which was constructed in a previous study (1; this plasmid was erroneously described to contain a PEND sequence from nucleotide 227 to 482). Proteins were finally dialyzed against stock buffer (20 mM HEPES/NaOH pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), mixed with 0.5 vol glycerol (33% final concentration) and stored at –15°C in an unfrozen state.

Figure 2.

Intermolecular interaction of cbZIP domains. (A) Binding of GST fusion proteins to the immobilised MBP fusion proteins. The MBP fusion proteins along with MBP alone were separated by SDS–PAGE, and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The first piece of membrane was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue to show protein bands. The other pieces were reacted with various GST fusion proteins as indicated. After washing, the GST was located by anti-GST antibody (goat) and anti-goat IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase. The phosphatase activity was visualized by color reaction. The numbers on the left indicate molecular mass markers. (B) Binding of MBP–BZ to immobilized GST fusion proteins. The GST fusion proteins as well as GST were separated by SDS–PAGE and then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The first piece of membrane was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue to show protein bands. The other pieces were reacted with MBP–BZ fusion protein. After washing, the MBP was located by anti-MBP antibody (rabbit) and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase. The phosphatase activity was visualized by color reaction. The numbers on the left indicate molecular mass markers. (C) Schematic diagram of the PEND protein showing the location of the partial polypeptides used in the experiments in (A) and (B). An extended zipper region consisting of two parts is shown here, but the second half of the zipper region is not conserved in the Brassica and Arabidopsis sequences.

To avoid contamination of Escherichia coli DNA, GST–BZ2 was purified by gel filtration in 0.5 M NaCl and used for selection of binding sites in Figure 4. For gel mobility shift analysis, the GST–BZ protein, which had been affinity-purified from DNase-treated E.coli extract, was cleaved with thrombin at 20°C for 3 h according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then GST was removed by repeated passage through a column of glutathione–Sepharose 4B. The unbound fraction (BZ), mostly free of GST and GST–BZ, was concentrated and stored in the presence of glycerol as described above.

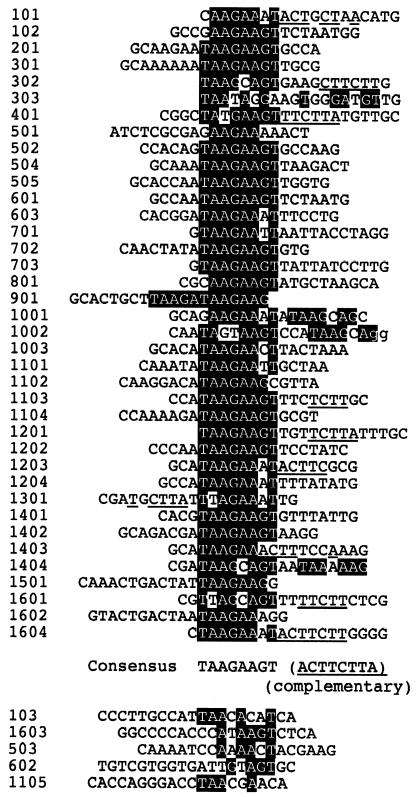

Figure 4.

Selection of target DNA sequence for the GST–BZ2 protein from random sequence pool. Sequences that have affinity with the GST–BZ2 protein were selected from a random sequence pool. The common sequence motif TAAGAAGT is highlighted. The underlined residues show additional similarity to the complementary sequence ACTTCTTA. The five sequences shown below had a limited similarity to the consensus sequence. The residues in lower case are part of the primer region. The numbers on the left are sequence identifiers.

Far-western blot analysis

The GST fusion proteins (∼1 µg/lane) were separated by SDS–PAGE using a 12% gel, and then blotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membrane was incubated with one of the MBP fusion proteins, and then successively reacted with rabbit antibodies raised against MBP (New England Biolabs) and antibodies raised against rabbit IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Zymed). The signal was finally visualized by color reaction with NBT and BCIP (Promega). In a similar way, MBP fusion proteins were separated and blotted onto a PVDF membrane and reacted with GST fusion proteins. The GST was visualized with goat antibodies raised against GST (Amersham/Pharmacia) and antibodies raised against goat IgG conjugated with alkaline-phosphatase (Zymed).

Cross-linking analysis

The BZ protein (1 µg in 20 µl) that had been dialyzed against PBS (0.14 M NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 10 mM Na,K-phosphate pH 7.0) was mixed with either 1 µl of 10 mM bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate (BS3; Pierce) in 5 mM Na-citrate pH 5.0 or 1 µl of 15 mM 1,5-difluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DFDNB; Pierce) in methanol, and allowed to react on ice for 10 min. Then, 1 µl of 1 M Tris–HCl pH 7.5 was added to quench the cross-linking reagents. Ten minutes later, an equal volume of 2× SDS–PAGE sample buffer was added. Then, 10 µl per lane was analyzed by SDS–PAGE with a 15% polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with silver nitrate using the Silver Staining Kit (Wako Pure Chemicals).

Selection of binding sites from random sequence pool

Selection of binding sites for the GST–BZ2 protein from a random sequence pool was performed according to the method of Pierrou et al. (16), using the following template and primers: SelTempB20, 5′-TTCTCGACTCGAGATACC(N)20CGAGATCTAGACGTTAGC; SelTopB, 5′-TTCTCGACTCGAGATACC; SelBotB, 5′-GCTAACGTCTAGATCTCG.

The double-stranded DNA was synthesized from SelTempB20 and SelBotB with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (New England Biolabs). This DNA (10 µg) was mixed with GST–BZ2 (1 µg) in a 100 µl binding mixture containing 10 mM HEPES/KOH pH 7.7, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 µg/ml poly(dI–dC) and 0.5 µg/ml poly(dA–dT), and then applied to a column (30 µl bed volume) of glutathione–Sepharose 4B. After the column had been thouroughly washed, bound DNA was eluted with 0.5 M KCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, and a sample was amplified by PCR using the two primers. The conditions for the PCR were: 1 min at 94°C, 25 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 45 s at 60°C and 45 s at 72°C, and 2 min at 72°C. The affinity selection and PCR were repeated six times. The resulting DNA was digested with XbaI and XhoI, and cloned in pBluescript SK+ for sequencing.

Gel mobility shift analysis

Gel mobility shift analysis of DNA binding was performed essentially as described previously (1). The BZ protein was prepared by cleavage of GST–BZ with thrombin (see above). The PEND protein was purified from developing chloroplasts of 6-day-old pea seedlings as described previously (1). The synthetic probes used in the present study are shown in Figure 5B. The 5′ ends of the probes were labeled by polynucleotide kinase (Takara Biomedicals) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP (New England Nuclear), and purified by a spin column (1 ml bed volume) filled with Sephadex G-25 (Amersham/Pharmacia). After electrophoresis, the gel was dried on a cellophane sheet and then subjected to autoradiography with Fuji RX film. The density of the bands on the X-ray film image was analyzed with the NIH-image program.

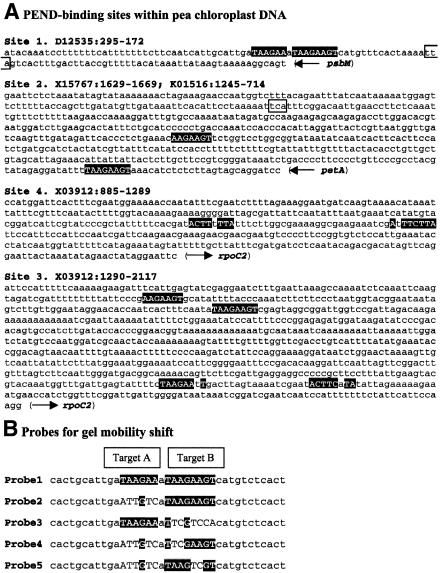

Figure 5.

(A) Localization of the canonical target sequence for the cbZIP domain within the previously identified binding sites for the PEND protein. Sites 1–4 were described by Sato et al. (1). Site 1, a 0.17 kb minimal binding region near the psbM gene within the initially identified site 1; site 2, a 0.5 kb region containing the downstream half of the petA gene; sites 4 and 3, consecutive regions within the rpoC2 gene. The canonical target sequence for the cbZIP domain is highlighted by white uppercase characters on a black background. The stop codons are shown by boxes. The rest of the sequences is printed in lowercase characters. (B) Double-stranded DNA probes used for the gel mobility shift experiments. Probe 1 sequence (40 bp) was taken from the tandemly repeated canonical target sequence of site 1. Probe 2 contains mutated target A, while probe 3 contains mutated target B. Probes 4 and 5 are derivatives of probe 2 that contained partially mutated target B. Residues in the target sites are printed in uppercase while other residues are printed in lowercase.

RESULTS

Comparison of cbZIP domains with known bZIP domains

Close examination of the basic region of the PEND polypeptide (Fig. 1) showed that the positions of basic amino acid residues are different in the PEND polypeptide from those in plant bZIP proteins. The common motif or pattern of the basic region of typical bZIP domains (Prosite accession no. PS00036) was not found in the basic region of the PEND polypeptide. In this respect, the DNA-binding region of the PEND polypeptide is not a bZIP domain. A BLAST search of the GenBank database (release 112) revealed that two more plant protein sequences were found highly homologous to the DNA-binding domain of the PEND polypeptide. One was the GS-box binding factor 1 (GSBF1) of Brassica napus (13), and the other was a putative PEND or GSBF1 homolog of Arabidopsis thaliana (GenBank ID ATF4F15, ORF number 280). No additional protein-coding sequences have been found in the current GenBank database (release 121) or the complete A.thaliana genome. All three sequences are highly homologous in the putative bZIP region as well as the C-terminal transmembrane domain (data not shown), although the six times repeat discovered in the pea PEND polypeptide was imperfectly conserved in the Brassica and Arabidopsis sequences (see Fig. 2C for diagram of structure). Since the N-terminus of the purified PEND protein has been identified as Ala16 (1), the preceding short sequence of 15 residues was judged to be a presequence. The putative presequences of these three proteins are all 15 residues long and highly conserved (Fig. 1). Detailed analysis of the localization and chloroplast targeting signal of the PEND protein will be published elsewhere (Y.Ohki, K.Hashimoto and N.Sato, manuscript in preparation).

The three PEND-like sequences are also different from the nuclear transcription factors in the hinge region, which is located between the basic region and the zipper region. In addition, many of the heptad leucine residues are replaced by other hydrophobic residues such as valine, isoleucine, or phenylalanine in the PEND-like sequences. Since the conservation of the leucine residue is not obligatory for the dimerization of zipper domain (11), the presence of various hydrophobic residues at the heptad positions might not directly disprove the dimerization function of the zipper domain of the PEND polypeptide. These results suggest that the three PEND-like sequences represent a novel type of bZIP domains. To distinguish these novel domains from the classic, nuclear bZIP domains, ‘cbZIP’ (for chloroplast bZIP) will be used hereafter, though the localization of these proteins might need further examination (see Discussion).

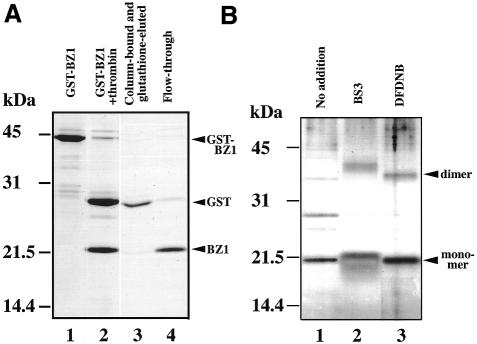

Homodimerization of cbZIP domains

To demonstrate that the cbZIP domains can interact with each other, two series of Far-western blotting experiments were done (Fig. 2). In the first series (Fig. 2A), MBP fusion proteins, MBP–BZ and MBP–CC, were blotted on a membrane, then incubated with GST fusion protein, GST–BZ, GST–CC or GST–BZ2 and finally visualized with anti-GST antibodies and alkaline phosphatase-linked secondary antibodies. GST–BZ and GST–BZ2 reacted with MBP–BZ on the membrane (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 and 11). MBP–CC did not react with GST–CC under the experimental conditions (Fig. 2A, lane 9). In a complementary series of experiments, the GST fusion proteins were blotted on a membrane and reacted with MBP–BZ (Fig. 2B). MBP–BZ reacted with GST–BZ and GST–BZ2 (Fig. 2B, lanes 6 and 7). These results clearly show that the cbZIP domains can interact with each other. In contrast, this blotting experiment did not provide evidence that the putative CC domains of the PEND polypeptide can bind to each other.

Oligomer state was also analyzed by gel filtration. The BZ protein, which was obtained by cleavage of the GST–BZ protein (Fig. 3A), was analyzed by gel filtration on a Superdex 75HR column. The BZ protein (13.4 kDa monomer) was eluted as a 33 kDa protein (results not shown). Judging from the apparent molecular mass, this complex was likely to be a dimer.

Figure 3.

Homodimerization of the cbZIP domain. (A) Cleavage of the GST–BZ protein with thrombin and preparation of the BZ protein. The proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE using a 15% gel and then stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Lane 1, original GST–BZ protein; lane 2, GST–BZ protein after treatment with thrombin; lane 3, proteins bound to the column of glutathione–Sepharose 4B and eluted with glutathione; lane 4, unbound proteins. The numbers on the left indicate molecular mass markers. Note that the 13.4 kDa BZ polypeptide migrated as a 21 kDa protein. (B) Cross-linking of the BZ protein. The BZ protein was cross-linked with BS3 or DFDNB and then analyzed by SDS–PAGE with a 15% gel. The proteins were stained with silver nitrate. The numbers on the left indicate molecular mass markers. The arrowheads indicate the monomer and dimer of BZ. Lane 1, no addition; lane 2, BS3; lane 3, DFDNB.

Dimerization was confirmed by cross-linking BZ protein with a water-soluble N-hydroxysuccinimide ester reagent, BS3, or a hydrophobic divalent aryl fluoride, DFDNB (Fig. 3B). The BZ protein co-migrated with a 21 kDa polypeptide because of its positive charges. A band at ∼42 kDa was found after the cross-linking. These results suggest that the cbZIP domain exists as a dimer in solution. The small difference in the mobility of proteins cross-linked with the two reagents reflects the difference in hydrophobicity of the reagents.

Selection of binding sites for the cbZIP domain from random sequence pool

Previously, we identified four sites on the pea chloroplast genome that had affinity for the PEND protein (1,2). But we were unable to pinpoint the target sequence of the PEND protein. Now we have selected sequences that have affinity for the GST–BZ2 fusion protein from a random sequence pool. We finally obtained 43 sequences (Fig. 4). Among them, 38 sequences shared a sequence, 5′-TAAGAAGT. Some selected sequences contained slightly different residues, but in these cases, an additional imperfect copy of the consensus sequence was found (sequences 101, 302, 303, 401, 1103, 1301, 1404 and 1601). The other five sequences shown below exhibited only a limited similarity to the canonical target sequence, and might represent imperfectly selected sequences. The sequence TAAGAAGT was also found in the four PEND-binding sites (sites 1–4) on the pea chloroplast genome, identified previously (1) (Fig. 5A): each of sites 1, 2 and 3 contained a copy of this octamer sequence as well as one to three sequences with a single mismatch, whereas site 4 contained two octamer sequences with a single mismatch. Although the complete sequence of the pea chloroplast genome is not available, two to 13 copies of the octamer motif were found in various completely sequenced chloroplast genomes (results not shown). There is no clear-cut relationship between the phylogeny and the copy number of the octamer sequence.

Gel mobility shift analysis

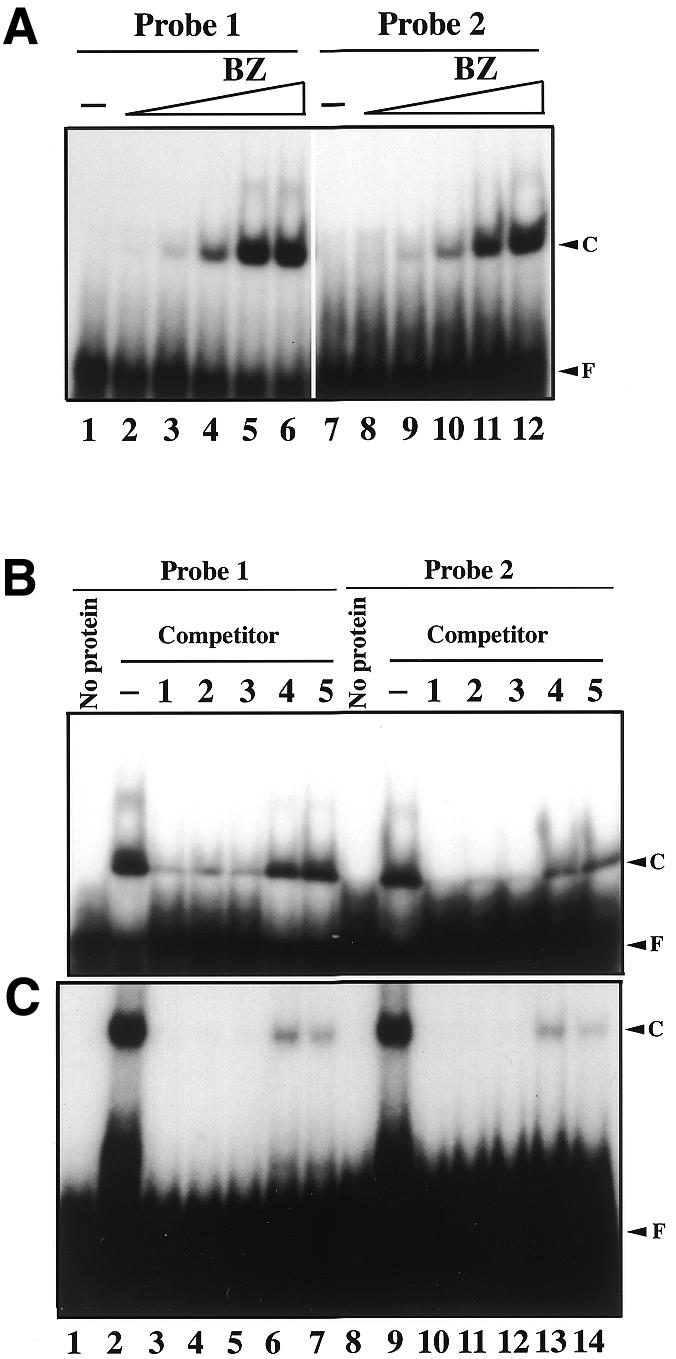

To verify that the octamer sequence is a preferred target for the cbZIP domain of the PEND polypeptide, gel mobility shift analysis was performed (Fig. 6). A 40 bp double-stranded synthetic DNA that corresponds to the octamer-containing region of site 1 was used as a parent probe (probe 1 in Fig. 5B). This region contains tandemly duplicated octamer sequences, complete (target B in Fig. 5B) and imperfect (target A). Probes 2 and 3 are mutated probes that contained only one target. Probes 4 and 5 are mutants derived from probe 2. In preliminary experiments, the GST–BZ protein bound to probe 1, while GST alone had no affinity with the probe tested (results not shown). Then the BZ part was cleaved from the GST–BZ protein and tested for the affinity for the probes. The BZ protein formed a complex with probes 1 and 2 (Fig. 6A). The affinity of BZ to probe 1 (Kd = 240 nM) was slightly higher than that to probe 2 (Kd = 600 nM). Since the mobility of the shifted bands obtained with both probes was similar, only one of the two target sequences within probe 1 must be used for the binding with BZ protein. Figure 6B shows the results of competition experiments. The binding of probe 1 was partially competed by unlabeled probes 1, 2 and 3, whereas the binding of probe 2 was effectively competed by the three unlabeled competitors. In both cases, probes 4 and 5 were ineffective competitors. The affinity for the BZ protein is therefore in the following order: probe 1 > probe 2 = probe 3 > probe 4 = probe 5. This suggests that the two AA sequences within the canonical target sequence are important for the binding of the BZ protein to the target DNA. In this respect, the second imperfect octamer, AtTTCTTA, in site 4 (identical to target A) must be a functional binding site, while the fourth octamer, ACTTCaTA, in site 3 might not be a high affinity binding site.

Figure 6.

Gel mobility shift analysis of the binding specificity of the cbZIP domain and the PEND protein. (A) Concentration dependence of binding of the BZ protein (1.5 µM) with probes 1 and 2. Lanes 1–6, probe 1 (12 nM); lanes 7–12, probe 2 (12 nM). Lanes 1 and 7, no protein; lanes 2 and 8, 15 nM BZ; lanes 3 and 9, 50 nM BZ; lanes 4 and 10, 150 nM BZ; lanes 5 and 11, 500 nM BZ; lanes 6 and 12, 1.5 µM BZ. F, free probe; C, DNA–protein complex. (B) Radiolabelled probe 1 or 2 (12 nM) was mixed with BZ (1.5 µM) in the presence of 100-fold molar excess (1.2 µM) of unlabeled competitors. Lanes 1–7, probe 1; lanes 8–14, probe 2. Lanes 1 and 8, no protein and competitor; lanes 2 and 9, no competitor; lanes 3 and 10, probe 1 as a competitor; lanes 4 and 11, probe 2 as a competitor; lanes 5 and 12, probe 3 as a competitor; lanes 6 and 13, probe 4 as a competitor; lanes 7 and 14, probe 5 as a competitor. (C) Similar competition experiments with the purified PEND protein (60 nM). The lanes correspond to those in (B).

The PEND protein, which had been purified from developing chloroplasts, was also tested in similar competition experiments (Fig. 6C). The results were very similar to those obtained with the BZ protein, and again probes 4 and 5 were ineffective competitors. These results suggest that the binding specificity of the native PEND protein is similar to that of the isolated cbZIP domain.

DISCUSSION

Basic characteristics of the cbZIP domain

The results of the present study indicate that the cbZIP domain of the PEND polypeptide is a dimeric DNA-binding domain that has an affinity for the canonical octamer sequence TAAGAAGT. The two AA sequences were shown to be important for the binding. Although sequence comparison indicated that the cbZIP domain is significantly different from the classic bZIP domain with respect to the zipper region (Fig. 1), the cbZIP domain indeed forms a dimer, as do bZIP domains. We also note the presence of dipeptides KE and RE in the zipper region of the cbZIP domain (Fig. 1). A helical wheel analysis (not shown) suggests that these residues can form intermolecular salt bridge pairs and stabilize the CC structure of the zipper region.

The target DNA sequence for the cbZIP domain is quite different from those reported for bZIP proteins. The target site of the Opaque2 protein, a bZIP protein, consists of TGAC half sites (17). Most of the recognition sequences of bZIP proteins contain a palindrome sequence as a reflection of dimeric binding (18), but the target sequence of the cbZIP domain does not apparently fit to this rule.

A Brassica homolog of the PEND protein, GSBF1, is known to bind to the so-called split G-box or GS-box, namely CAC-N12–14-GTG, in vitro (13). However, a close examination of the GS-box sequences indicates that the internal sequence of the GS-box (the N12–14 region) is similar to the target sequence of the PEND polypeptide, if some mismatches are allowed. Further study is necessary for resolving this discrepancy in the binding sites.

Chloroplast localization of the PEND protein

We showed previously that the PEND protein is present in the envelope membrane of the developing chloroplast. Results of N-terminal sequencing of the purified PEND protein indicated that the N-terminal 15 residues of the predicted PEND polypeptide were removed by processing. The cleavage site fits to the specificity of known processing sites of the chloroplast processing enzyme (19). Although the bZIP domain contains a bipartite nuclear targeting signal (10), the cbZIP domain lacks the nuclear localization signal (Fig. 1). We also have evidence that the PEND polypeptide is targeted to the chloroplast both in vitro and in vivo (unpublished results). Curiously, the prediction of intracellular localization by the chloroP program (version 1.1) (20) did not support the chloroplast localization of the PEND polypeptide. This might be explained by the fact that the prediction capacity of a neural network program depends on the data sets used for training the system, and this failure of prediction does not disprove the chloroplast localization of the PEND protein. The cbZIP domain is, therefore, a new type of dimeric DNA-binding domain of a chloroplast protein. The GSBF1 protein is highly homologous to the PEND polypeptide, but has been shown to be a nuclear transcription factor (13). We need further experiments to resolve this discrepancy.

Binding sites and probable functions of the native PEND protein

Although the exact role of the binding of chloroplast nucleoids to the envelope membrane is yet to be elucidated, the PEND protein is a candidate for the membrane anchor of the chloroplast nucleoids (1,2,4). The replication and transcription of a genome take place on a solid support such as the cytoplasmic membrane in bacteria or nuclear matrix in eukaryotes, though the exact role of this anchoring has not been shown. The binding of the chloroplast nucleoids to the envelope membrane is similar to this observation. As stated in previous papers (1,2), the binding of nucleoids to the envelope membrane can ensure even partitioning of the nucleoids to daughter chloroplasts. Although the complete sequence of the pea chloroplast DNA is not known, a search in the org.dat file of EMBL database release 62 indicated that the canonical binding site, TAAGAAGT, is present in various parts of pea chloroplast DNA, such as the psbC gene (accession no. M27309), the petB2 intron (AF153442), the psbA gene (M16899), the trnT gene (X04761) and the atpH gene (M57711) as well as the sites presented in Figure 5A. Results of a previous study (2) showed that the DNA fragments containing the five genes listed above did not significantly bind to the PEND protein in South-western analysis and PCR-based site selection. The most plausible explanation is that the previously identified sites represent high affinity binding sites. High affinity binding of the PEND protein is likely to require multiple target sequences that are present in the vicinity as seen in Figure 5A and evidenced by the comparison of affinities of probe 1 (two targets) and probe 2 (single target) (Fig. 6A). Other sites were not recognized as binding sites under stringent binding conditions used in the South-western analysis with high concentrations of blocking or competition reagents such as calf-thymus DNA and skim milk.

It is hard to predict the probable function of the PEND protein within the chloroplast just by the target sequence of the cbZIP domain. However, we noticed that the target sequence of the PEND protein is similar to the AAG box reported earlier in barley (21) and non-consensus-type plastid promoters in tobacco (22). The PEND protein with a cbZIP domain can therefore be involved in the transcriptional regulation of chloroplast genes during an early phase of chloroplast development, and this possibility should be studied in the future.

The PEND protein or its homologs are found only in pea, Arabidopsis and Brassica in the current database. It has no obvious homolog in the cyanobacterial genomes sequenced so far. A plausible origin of the PEND protein is a duplication and modification of existing DNA-binding proteins during the evolution of the green plants. According to our hypothesis on the discontinuous evolution of the plastid genetic machinery (23), most of the prokaryotic DNA-binding proteins had been lost early after endosymbiosis, while the prokaryotic chloroplast DNA persisted. New regulators of chloroplast DNA expression became necessary during the evolution of the land plants, which change their morphology drastically during their life cycle to overcome various environmental stresses. We suggest that the PEND protein is one such new regulator acting during the early phase of chloroplast development, which appeared during the evolution of the land plants, most probably by changing the structure of a nuclear bZIP protein.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (nos 10170202, 11151202 and 11440232) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology, Japan.

References

- 1.Sato N., Ohshima,K., Watanabe,A., Ohta,N., Nishiyama,Y., Joyard,J. and Douce,R. (1998) Molecular characterization of the PEND protein, a novel bZIP protein present in the envelope membrane that is the site of nucleoid replication in developing plastids. Plant Cell, 10, 859–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato N., Albrieux,C., Joyard,J., Douce,R. and Kuroiwa,T. (1993) Detection and characterization of a plastid envelope DNA binding protein which may anchor plastids nucleoids. EMBO J., 12, 555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuroiwa T. (1991) The replication, differentiation, and inheritance of plastids with emphasis on the concept of organelle nuclei. Int. Rev. Cytol., 128, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato N., Rolland,N., Block,M.A. and Joyard,J. (1999) Do plastid envelope membranes play a role in the expression of plastid genome? Biochimie, 81, 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato N., Misumi,O., Shinada,Y., Sasaki,M. and Yoine,M. (1997) Dynamics of localization and protein composition of plastid nucleoids in light-grown pea seedlings. Protoplasma, 200, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyamura S., Nagata,T. and Kuroiwa,T. (1986) Quantitative fluorescence microscopy on dynamic changes of plastid nucleoids during wheat development. Protoplasma, 133, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Shea E.K., Klemm,J.D., Kim,P.S. and Alber,T. (1991) X-ray structure of the GCN4 leucine zipper, a two-stranded, parallel coiled coil. Science, 254, 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller W., König,P. and Richmond,T.J. (1995) Crystal structure of a bZIP/DNA complex at 2.2 Å: determinants of DNA specific recognition. J. Mol. Biol., 254, 657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menkens A.E., Schindler,U. and Cashmore,A.R. (1995) The G-box: a ubiquitous regulatory DNA element in plants bound by the GBF family of bZIP proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci., 20, 506–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varagona M.J., Schmidt,R.J. and Raikhel,N.V. (1992) Nuclear localization signal(s) required for nuclear targeting of the maize regulatory protein Opaque-2. Plant Cell, 4, 1213–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vettore A.L., Yunes,J.A., Neto,G.C., da Silva,M.J., Arruda,P. and Leite,A. (1998) The molecular and functional characterization of an Opaque2 homologue gene from Coix and a new classification of plant bZIP proteins. Plant Mol. Biol., 36, 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson J.D., Higgins,D.G. and Gibson,T.J. (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldmüller S., Müller,U. and Link,G. (1996) GSBF1, a seedling-specific bZIP DNA-binding protein with preference for a ‘split’ G-box-related element in Brassica napus RbcS promoters. Plant Mol. Biol., 32, 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato N. (2000) SISEQ: manipulation of multiple sequence and large database files for common platforms. Bioinformatics, 16, 180–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schäffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierrou S., Enerbäck,S. and Carlsson,P. (1995) Selection of high-affinity binding sites for sequence-specific, DNA binding proteins from random sequence oligonucleotides. Anal. Biochem., 229, 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yunes J.A., Vettore,A.L., da Silva,M.J., Leite,A. and Arruda,P. (1998) Cooperative DNA binding and sequence discrimination by the Opaque2 bZIP factor. Plant Cell, 10, 1941–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niu X., Renshaw-Gegg,L., Miller,L. and Guiltinan,M.J. (1999) Bipartite determinants of DNA-binding specificity of plant basic leucine zipper proteins. Plant Mol. Biol., 41, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter S. and Lamppa,G.K. (1998) A chloroplast processing enzyme functions as the general stromal processing peptidase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 7463–7468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emanuelsson O., Nielsen,H. and von Heijne,G. (1999) ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Prot. Sci., 8, 978–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim M. and Mullet,J.E. (1995) Identification of a sequence-specific DNA binding factor required for transcription of the barley chloroplast blue light-responsive psbD-psbC promoter. Plant Cell, 7, 1445–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapoor S., Suzuki,J.Y. and Sugiura,M. (1997) Identification and functional significance of a new class of non-consensus-type plastid promoters. Plant J., 11, 327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato N. (2001) Was the evolution of plastid genetic machinery discontinuous? Trends Plant Sci., 6, 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]