Abstract

Sensationalistic media coverage has fueled stereotypes of the Mexican border city of Tijuana as a violent battleground of the global drug war. While the drug war shapes health and social harms in profoundly public ways, less visible are the experiences and practices of hope that forge communities of care and represent more private responses to this crisis. In this article, we draw on ethnographic fieldwork and photo elicitation with female sex workers who inject drugs and their intimate, non-commercial partners in Tijuana to examine the personal effects of the drug war. Drawing on a critical phenomenology framework, which links political economy with phenomenological concern for subjective experience, we explore the ways in which couples try to find hope amidst the horrors of the drug war. Critical visual scholarship may provide a powerful alternative to dominant media depictions of violence, and ultimately clarify why this drug war must end.

Keywords: Mexico, critical phenomenology, drug war, hope, injection drug use, photo elicitation

The Mexico–USA border is a key site of the global assault against drug use. In the United States, the Nixon administration was well known for launching the militaristic “War on Drugs” against domestic drug use and illicit trade, although historically, efforts to regulate domestic drugs date back to the early 1900s (Inciardi 2002). By 2015, US drug war expenditures exceeded $26 billion annually and primarily targeted interdiction and supply eradication efforts (Drug Policy Alliance 2015). South of the US border, the drug war entered a particularly violent period in Mexico beginning in 2006 when then-President Calderón launched a military offensive against cartels that resulted in more than 121,000 deaths, of which 65,000–80,000 were organized crime-style homicides (Heinle, Ferreira, and Shirk 2016). Between 2007 and 2011 alone, Mexico’s homicide rate tripled from 8.1 to 23.5 homicides per 100,000, reaching “epidemic” levels according to World Health Organization standards (Heinle, Molzahn, and Shirk 2015). Sensationalistic media coverage of this period of drug-related violence has simplified the issues and exoticized Mexico as a dangerous “Other”. Yet manifestations of what we heretofore call the “drug war” on both sides of the Mexico–USA border are inexorably linked, as the majority of drugs transported through Mexico are destined for US consumption and vast numbers of cartel weapons have US origins (Boullosa and Wallace 2015).

On both sides of the Mexico–USA border, where militarization, interdiction efforts, and forms of drug surveillance are highly visible, the war also has less-noted but profoundly detrimental effects on communities. Gruesome media representations of the war have fueled stereotyped understandings of the border city of Tijuana as a particularly violent war zone. Although Tijuana is an important transit point for heroin and methamphetamine destined for US markets (Brouwer et al. 2006), depicting the impact of this war in death counts and militaristic terms glosses over the multitude of other health and social harms that have resulted. In particular, the policies, practices, and ideologies underlying this war cast people who use drugs as somehow responsible for the problem, thereby obscuring the structural factors at play and exacerbating their social and economic marginalization (Singer and Page 2014). Despite intensified research attention to global wars and forms of violence, few studies have interrogated the more human effects of the drug war in Mexico (Garcia 2015). In this article, we suggest that critical ethnographic and visual anthropological perspectives are well suited to expose the pernicious effects of the drug war by illustrating the personal experiences of drug users who are ensnared in the crossfire.

Toward a critical phenomenology of the drug war

Based on our long-term engagement in public health studies of drug use and HIV risk along the Mexico–USA border, we build a critical phenomenology (Desjarlais 1997) of the drug war in relation to the major battleground city of Tijuana. Critical phenomenology links political economic factors that configure life possibilities with phenomenological concern for subjective experience. Medical anthropologists frequently draw on critical perspectives to demonstrate how sex work, drug use, violence, and HIV and AIDS are historically and structurally produced (Bourgois 2003; Rhodes et al. 2011; Singer 1998). A rich body of anthropological scholarship on health and illness has also drawn on phenomenological concepts privileging experience, embodiment, and subjectivity (Biehl, Good, and Kleinman. 2007; Csordas 1993; Kleinman 1988). Desjarlais (1997) has called for anthropologists to specifically link political economic and phenomenological frames through a “critical phenomenology” approach. Using a lens of hope, we draw connections between the structural violence of the drug war and its intimate effects on the experiences of people who use drugs.

On a global level, we conceptualize the drug war as part of a larger biopolitical agenda that has resulted in widespread misery disproportionately affecting poor and marginalized populations. Increasingly, interdisciplinary researchers and practitioners are calling for a reconceptualization of the drug war that will bring it to an end (Csete et al. 2016; Godlee and Hurley 2016). Borrowing from David Graeber’s analysis of modern capitalist systems, we view this war as part of a broader “machinery of hopelessness” created and enforced by the global military-industrial complex, law enforcement, border security, surveillance systems, the media, and other forms of biopower that serve to “shred and pulverize the human imagination [and] destroy our ability to envision an alternative future” (Graeber 2009). In contrast to hopelessness and despair, hope is a concern with imagined futures. In particular, media institutions hold power to “shape the imaginative context in which we live” (Harvey 2000:165), thereby limiting our ability to contemplate alternative solutions. In contexts of conflict, media depictions can dehumanize people and generate apathy by leaving people feeling hopeless and incapable of enacting change (Avni 2006). Sensationalistic media stories of the drug war “serve to reinforce a narrative that’s been ingrained into our media culture: Drug crises are unpredictable, dangerous, and can only be dealt with the firm hand of the criminal justice system” (Werb 2016). In Mexico, images of gruesome drug violence not only divert attention from the futility of drug control tactics (Sharp 2014) but fuel misrecognition that violence is a necessary response to drug-related “threats” to society, and misery is deserved by those who continue to use drugs despite the war efforts.

On the ground, this “machinery of hopelessness” enacts its harms both politically and phenomenologically. The Mexico–USA border has the greatest level of socioeconomic inequality between any two contiguous countries in the world (Clemens, Montenegro, and Pritchett 2009). With a highly mobile population nearing 1.7 million people, Tijuana is the largest Mexican border city and shares one of the world’s busiest land border crossings with San Diego, California. Since US Prohibition, Tijuana has supported a leisure economy involving its famous Zona Roja (Red Light District), where gambling venues, bars, strip clubs, and availability of drugs and street- and hotel-based sex for purchase create a chaotic tourist atmosphere. While larger trends in economic development and threats of drug violence have reinforced unemployment and inequality in Tijuana, the Zona’s persistence has contributed to linked epidemics of sex work, substance use, and epidemics of HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Katsulis 2009; Strathdee et al. 2011). Although HIV prevalence among adults is low throughout Mexico (0.2 percent nationally), transmission remains concentrated among “high risk” groups in Tijuana, where prevalence reaches 3.4 percent among people who inject drugs, 5 percent among female sex workers, and 7.3 percent among female sex workers who inject drugs (Strathdee et al. 2012).

Tijuana has among the highest levels of drug use per capita in Mexico, in part due to “spillover” from northbound drug trafficking (Brouwer et al. 2006). In response to growing concerns around drug use and related health harms, Mexico recently joined a broader Latin American movement toward harm reduction by decriminalizing small amounts of drugs for personal possession in 2009 (Robertson et al. 2014). While this policy has alternatively been criticized and praised as a hopeful alternative to drug control and criminal justice approaches, the ethnographic landscape nevertheless remains challenging for those affected by drug use (Werb et al. 2014). Although harm reduction services such as syringe exchange programs are variously available in Tijuana, inadequate funding and unstable political commitment have prevented these services from reaching all those in need (Philbin et al. 2008). Local policing practices (e.g., targeting users for arrest, patrolling specific areas, confiscating syringes) have further impinged upon injectors’ ability to adopt safer injection behaviors (Beletsky et al. 2013, 2015). Drug treatment services, which are supported under the new legislation, remain limited throughout Mexico and often involve abusive, punitive, and abstinence-based approaches (Bazzi et al. 2016; Garcia 2015), representing another form of structural violence integral to the drug war that blames “failure” to “succeed” on the individual rather than on treatment modality. Taken together, these structural conditions relating to the drug war imprint a false sense of responsibility upon people who use drugs for their own condition, adding to their everyday experiences of poverty, social exclusion, violence, and heightened HIV/HCV risk that characterize their “lived experience of embodied structural vulnerability” (Rhodes et al. 2011:211).

In juxtaposition to hopelessness, we conceptualize hope as both an existential lens to understand personal experience (Crapanzano 2003; Jensen 2016) and a form of practice (Mattingly 2010) to explore how the structural violence of the drug war becomes embodied among drug-using populations along the border. Hope is at once a deeply personal but complex cultural phenomenon situated within broader political, economic, and social processes (Harvey 2000; Novas 2006). As a form of practice, Mattingly eloquently writes that “[h]ope most centrally involves the practice of creating, or trying to create, lives worth living even in the midst of suffering, even with no happy ending in sight” (2010:6). Through this suffering, she suggests, new communities of care emerge as people come together to create shared meaning and find a sense of self-worth. Hope lies in a critical, liminal space between imagined futures of possibility and pragmatic daily survival amidst adverse conditions.

Our interest lies in exploring the experiences and practices of hope among couples who use drugs along the Mexico–USA border. Ethnographic research is well suited to reveal rarely-acknowledged forms of hope within the seemingly hopeless drug war. In line with this special issue, a further goal of our work is to integrate critical and phenomenological perspectives in medical anthropology with a complimentary visual anthropology. Visual data add depth and perspective to critical social analyses while posing new questions about representation that are particularly relevant to highly charged, sensitive topics like illicit drug use (Bourgois and Schonberg 2009). In the context of the drug war, we contend that photographs generated by people who use drugs and ethnographers who immerse themselves in situations to understand human experiences can provide a powerful alternative to dominant media depictions of violence.

How do we depict war?

This study was embedded within Proyecto Parejas, a social epidemiology study of HIV risk among female sex workers and their intimate male partners along the Mexico–USA border.1 Conducted from 2009 to 2012, our fieldwork took place at the height of drug war-related violence in Mexico. In 2011, we purposefully sampled six couples in Tijuana based on the female partner’s injection drug use, migration history, and rapport with the first author to generate an engaged sample whose heightened vulnerability to HIV also represented a diverse set of life experiences along the border. The project was designed to gain an in-depth understanding of these relationships, and included a visual component to elicit insight into how couples experienced and prioritized their daily lives. We were particularly interested in using photography to help assess the emotional dimensions of couples’ relationships (Edwards 2015; Pink 2006) in light of the harsh conditions of the drug war-ravaged border. Within this physical and emotional space of drug use, relationships, and struggle, an anthropology of hope emerged.

Following informed consent and life history interviews, individual participants were given disposable cameras with standardized instructions to photograph a typical day in their life, including the people, places, and activities that were important to them. Photo elicitation is a valuable method in contentious contexts in that it allows dangerous “Others” to generate images of places and people that researchers may never be able to see due to trust, timing, safety concerns, and other factors. One to two weeks later, we collected cameras from everyone (except one individual).2 Disposable cameras provided an easy, low technology option in this context.

After collecting cameras and developing participants’ photographs, we conducted individual or joint photo elicitation interviews, depending on the woman’s preference (Harper 2002; Ortega-Alcázar and Dyck 2012; Smith 2015). In open-ended interviews, we used each photograph as a prompt to explore everyday experiences. Following audio-recorded interviews, participants kept hard copy photographs and negatives while we kept digital copies. Our inductive analyses of interviews and fieldnotes are accompanied by selected images taken by the participants and authors in Tijuana between 2011 and 2015 to collaboratively co-construct narratives of the drug war.

We obtained written consent to disseminate participants’ photographs. Nonetheless, in deciding which photographs to include here, we carefully considered ongoing ethical debates and negotiations regarding identity politics (Perry and Marion 2010) and voyeurism of people who are poor and vulnerable. In particular, we considered how images can raise consciousness about overlooked and uncomfortable social issues (Farmer 1999) while inadvertently perpetuating marginalization and misinterpretation (Rhodes and Fitzgerald 2006). Bourgois and Schonberg (2009) decided to reveal identities in their work with homeless heroin injectors in San Francisco, drawing, in part, from a point made by their informant Nicki, who said, “if you can’t see the face, you can’t see the misery” (Bourgois and Schonberg 2009:11). Indeed, recent photojournalistic work in Tijuana has created powerful and humanizing portraits of the HIV risk environment experienced by marginalized groups (Cohen and Linton 2015).

In curating our project, we were inspired by Stone’s (2015) recent call for anthropologists to reconsider representations of structural violence. Drawing on Sontag’s “images of suffering” (1977) and critiques that using such images—even for altruistic work—can promote injustice (Kleinman and Kleinman 1996), Stone argues that a focus on corporality can erase the inequalities that ravage bodies in the first place, thus reinforcing dominant frameworks that naturalize suffering, ignoring the core issues at stake, and leaving little room for imagined alternative solutions. Stone calls instead for “scenes of confrontation” that highlight structural vulnerability without stripping subjects of their agency. This approach to visual narration of violence and suffering requires creativity, as “without being confronted or challenged in some way, viewers are not required to think analytically and nothing is made visible that was not already apparent” (Stone 2015:188).

We carefully deliberated over our decisions about inclusion of photographs. In selecting photographs, we prioritized the lesser-acknowledged, everyday effects of the drug war over images that could potentially replicate dominant media depictions of drug-violence, physically ravaged bodies of “addicts,” and other “uses of the useless” (Singer and Page 2014:21). In doing so, we offer no easy answers in determining what makes some visual images a method of “Othering” and others a contestation of this process. While none of our participants took photographs of violence or militarization,3 a significant proportion of photographs revealed identities (e.g., through self-portraits and photographs of friends and family) and frequently depicted graphic images of drug use including dangerous injections in the breast, neck, and groin. However, we made a conscious decision not to share such images because revealing faces could be misinterpreted as salacious gaze and the act of injecting does not reveal anything new in this context.

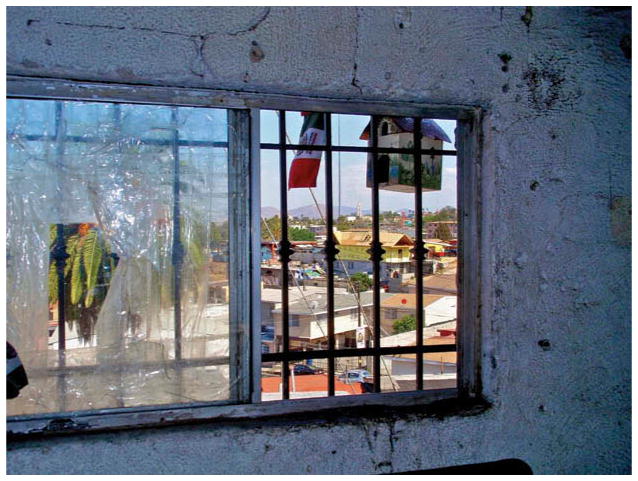

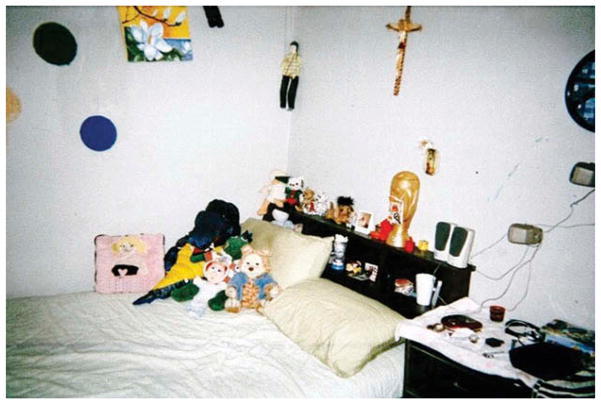

We are left with images of everyday, mundane contradictions and complexities of couples’ lives that we wish neither to demonize nor romanticize. These photographs, combined with our own from long-term immersion fieldwork, capture one particular version of the drug war as experienced by members of a marginalized border community. While ethnographies of drug use tend to depict public spaces such as streets, shooting galleries, and clinics, our research was also conducted within the safe havens of couples’ private homes (see Figure 1), offering a more intimate view of the drug war’s far-reaching and insidious effects (Syvertsen and Bazzi 2015).

Figure 1.

View of Tijuana from inside a couple’s home. Despite rapid economic development throughout Mexico and in the border region during recent decades, the economic gains have not been distributed equally. We spent most of our time with participants in their homes, which were basic and often substandard in terms of building materials, protection from the elements, and physical safety. Nevertheless, couples decorated these spaces to feel like home. Photograph by Angela Robertson Bazzi 2011.

Thematically, the following stories and photographs depict the drug war as a “machinery of hopelessness” through which paradoxical experiences and practices of hope emerge. Our own hope as researchers is that our work shows how the structural violence of the drug war shapes vulnerability to myriad health and social harms, and requires a more humanizing approach to drug policy, while it acknowledges the creative responses of people who use drugs as less visible dimensions of this war. The following stories examine the institutions, communities of care, family dynamics, and formation of “dangerous safe havens” (Syvertsen and Bazzi 2015) that couples use to develop hope amidst the horrors of the drug war.

Institutions of the drug war

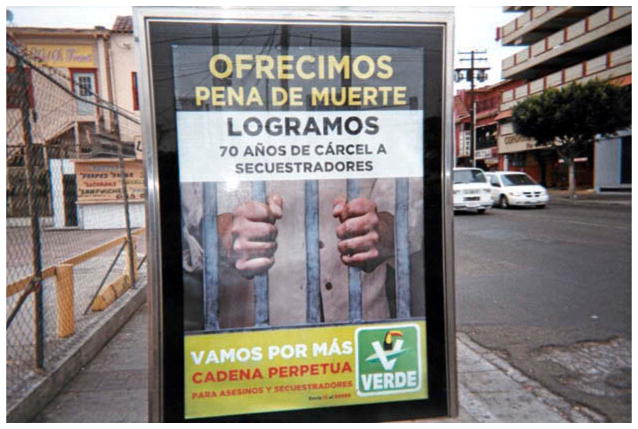

Institutions such as prisons, drug treatment centers, and hospitals comprise integral battlegrounds of the drug war, which are further complicated by an international border and legal restrictions regarding who can navigate it. Maria, 46, and Geraldo,4 40, met because of drugs. He knew that she smoked crack when they met, and purposefully started buying crack and coming around her San Diego neighborhood to invite her to use. Their now 20-year relationship has been marked by periods of separation, including several years that he spent incarcerated for drug-related offenses while Maria enrolled in drug treatment. Counter to any logic of the drug war, Geraldo acquired the habit of injecting heroin while in prison in Tijuana (see Figure 2). The day he was released, Maria picked him up, they promptly scored, and he showed her how to inject. He lamented, “You don’t know how sorry I am” for initiating her to injection, and he felt responsible for her heroin use. In contrast to dominant narratives of women being coerced into drug use by male partners, Maria said she started injecting because she was “tired of being sober” anyway.

Figure 2.

Photograph of a Green party political ad: “We offered the death penalty, we got 70 years in prison for kidnappers. Let’s go get life in prison for murderers and kidnappers.” Geraldo took this photograph in 2011 because it reminded him how much of his life he has spent incarcerated, primarily related to drug charges.

Unfortunately, Maria was unable to participate in the photo elicitation portion of the project because she was hospitalized for deep vein thrombosis in her leg (a mass that causes blockage in a distant part of the body). Geraldo explained that she had been taking large doses of ibuprofen far too frequently without eating to contend with the pain. One night when she started hallucinating, he got scared and called her family in San Diego for help. She later had a stroke and acquired a drug-resistant infection (MRSA) in the hospital. She remained hospitalized in San Diego for several months, where she was stabilized with methadone. Seeking health care in California was driven by cross-border health system inequalities, including perceptions of American health care superiority, lack of evidence-based treatment (i.e., opioid substitution therapy) in Mexican public hospitals, and reports of discrimination against people who use drugs by health care professionals in Tijuana.

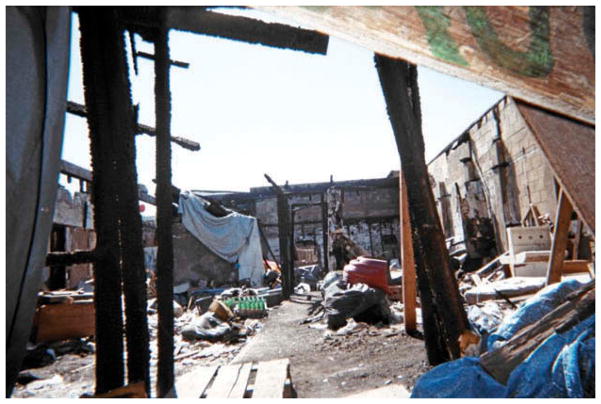

While Maria stayed in San Diego, Geraldo participated in the photo project because he said that Maria would want him to. His heavily drug-themed photographs provided insight into the structural conditions of his life, including his frequent attendance at a public picadero (shooting gallery) where he received help injecting in his neck. This particular picadero was an empty lot strewn with garbage and lacking running water where upwards of 40 people injected daily (see Figure 3). In such open spaces, users could quickly run away when sirens approached, or as Geraldo described, “hide in a garbage pile.” Punitive policing behaviors can rush injections and elevate health risks (Beletsky et al. 2013), upholding a pervasive sense of powerlessness embodied as a “fatalistic acceptance of harm and suffering” (Rhodes et al. 2011:212).

Figure 3.

One of many picaderos in Tijuana. Photograph by Geraldo 2011.

From a public health standpoint, picaderos are considered unsafe, unsanitary spaces where people use and share drugs in ways that heighten transmission of HIV/HCV. Anthropologically, picaderos could also be viewed as social spaces where forms of mutual care circulate in a “moral economy” (Bourgois 1998) wherein people pool money to buy drugs, assist one another with difficult injections, and ensure that people are present to help if overdoses occur. Picaderos thus have context-dependent social and public health risks and benefits. For Geraldo, visiting this site was a practice of hope in the context of despair: it provided inclusion into a community of care that helped him “get well” in the absence of his usual patterns of drug use with Maria.

Nearly in tears during one of his interviews, Geraldo described how he increased his drug use in Maria’s absence to cope with his emotional distress. He produced a photograph from his wallet from six years ago when he was released from prison and met up with Maria who had stopped using heroin while on the US side. He pointed out in an endearing way that she looked “gordita,” referring to the fullness in her face and her improved physical health, and explained that he privileged her current recovery efforts over his personal desires to see her. The wallet photograph represented a beacon of hope and symbol of strength in their decades-long relationship that had survived the institutions and border that separated them. No matter the circumstances, Geraldo held onto this hope and said that he and Maria “will always be together.”

Communities of care

Celia’s life was profoundly shaped by the drug war. While her intimate relationship was of critical importance, Celia’s family, friends, and other contacts from the streets of Tijuana formed an extended network that enabled mutual survival amidst shared conditions of deportation, exclusion, poverty, and drug use. Celia, 36, met her partner Lazarus, 43, in a Tijuana picadero. They formed a fast friendship hustling for money and drugs and eventually became intimately involved. Like her brothers, with whom she and Lazarus shared an apartment, Celia was deported after spending nearly her entire life in Southern California. Celia always spoke her mind, typically using multiple curse words to do so. She often wore loose fitting clothing in case she was stopped by the police and needed to feign pregnancy to try to avoid arrest by local police who arbitrarily harassed known and suspected drug users (Beletsky et al. 2013).

Celia and Lazarus’s rented apartment was located near the Tijuana River Canal. Known as El Bordo (an earthen dam or levee), the canal is a massive, recessed concrete waterway near the US border that runs adjacent to downtown and provides a shared meeting and living space for a growing population of migrants, deportees, and people who inject drugs (see Figure 4). Tijuana is one of the largest destinations for deportees in Mexico, overwhelming the city’s social and health services and leaving many, some of whom were raised in the United States and do not speak fluent Spanish, to seek refuge in places like the canal (Brouwer et al. 2009). At times, the stench of refuse and stagnant water is nauseating. On numerous occasions we observed public drug injection and makeshift tent cities that were erected between periodic police sweeps of the area.

Figure 4.

The Tijuana River Canal. Homeless migrants and people who use drugs have lived inside the western section of El Bordo since the 1980s and have been constant targets of policing and forced displacement. For example, a 2015 operativo (field operation) involving municipal and military law enforcement and local health authorities forced upwards of 500 people into drug rehabilitation programs lacking evidence-based services (Guerrero 2015). However, people have since returned to live and use drugs in El Bordo. Photograph by Jennifer Syvertsen 2011.

Within this harsh risk environment marked by drug violence, police brutality, homelessness, and unsanitary living conditions, Celia, Lazarus, and her brothers often let people from the canal take temporary refuge in their apartment. Although their second floor apartment did not have any private bedrooms, all household members had distinct sleeping spaces, including Celia’s small sanctuary in the kitchen area that she decorated and roped off with curtains. Every time we visited the apartment, the furniture was rearranged and decorations were reorganized. On different visits, we met a gaunt 13-year-old boy who Celia and her brothers were caring for, and Tito, a skinny “hit doctor” from El Bordo who was invited upstairs to help everyone inject. Tito had been out on the street with a makeshift cardboard tray wrapped around his neck selling dusty packs of gum and random knickknacks. After helping Celia and her brother inject in the bathroom, Tito took a hot shower and received a fresh change of clothes in this version of the moral economy.

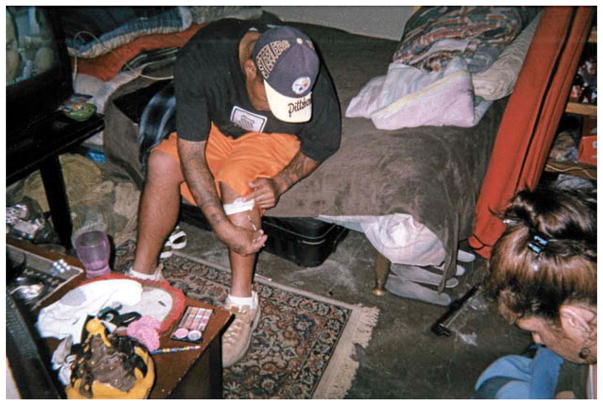

Celia and everyone else in the household participated in the sobreruedas (flea markets) that have formed a significant portion of the informal economy in Tijuana during recent years. With prison records, precarious documentation due to deportation, little formal education, and debilitating drug use, Celia and many of her friends and family members were excluded from formal employment. This exclusion shaped their participation in Tijuana’s growing and largely unregulated informal economy, which enabled their basic survival but also rendered them essentially invisible and ineligible for state-funded care. In the absence of other support, Celia, Lazarus, and her brothers formed their own community of care. Garcia (2014) has highlighted the vital forms of support that families of drug users provide for each other; casting such situations as “co-dependency” ignores implicit moral obligations and oversimplifies the depth of family ties. In Celia’s world, friends and canal refugees whose very sense of home was a casualty of the drug war joined this extended network of kin to enable mutual survival (see Figure 5). These relationships represented a community of care that provided support and hope where otherwise none existed.

Figure 5.

Injecting in private spaces like Celia and Lazarus’s apartment shields individuals from multiple health risks, including police harassment and the unsanitary conditions of public injection. While sharing needles or ancillary equipment heightens HCV/HIV risk, using in a private space may decrease infectious disease transmission because people injecting have more time to prepare and use their drugs, thereby reducing the risk of accidentally mixing up needles, cookers, cottons, water, or other injection equipment. Photograph by Lazarus 2011.

Children of the drug war

The children of the drug war are caught between bureaucratic intuitions and intimate communities of care where conflicting versions of children’s best interests clash. Mildred and Ronaldo, both 44, have been together since she found out she was pregnant eight years ago. Although their relationship was caring, their bond has been sustained largely due to the shared responsibility of raising their daughter. Lodged between a burned-down house on a garbage-strewn lot and a newly constructed two-story home likely funded by remittances, Mildred and Ronaldo lived in a modest single-story structure with a tenuous roof and broken window facing the street. Their front door opened into a dimly lit hallway partially blocked by a discarded toilet lodged in the corner. We conducted our interviews around a table in the kitchen, which was sparse other than simple appliances and a torn ET movie poster above the sink. Further into the house was a living room, bathroom, and two bedrooms; one used by Mildred, Ronaldo, and their daughter and the other by Ronaldo’s brother Marco and his girlfriend. During our interviews, we observed a consistent flow of mostly male drug users who were relatives or friends greeted by Marco and escorted into the bedroom. As in Celia’s apartment, Mildred and Ronaldo’s house functioned as a type of informal picadero.

While their home provided a safe haven for injection, it also drew heightened police surveillance. Ronaldo recounted an illegal search and seizure inside their home that culminated in their daughter being taken into state custody. Once there, social services requested her birth certificate, which the couple could not procure because, after she was born, they owed 6000 pesos (~US $450) to the General Hospital, which withheld her documents.5 Unable to pay, access to education and government health services was complicated. Ronaldo expressed anger over their treatment by the criminal justice, health care, and child welfare institutions.

To regain custody of their daughter, Mildred and Ronaldo underwent state-mandated drug testing, an enactment of biopower to regulate and control behavior among the poor. Because penalties for women were more severe due to the stigma against women who use drugs as bad, “selfish” mothers, the couple acquired a drug-free urine specimen to fake her test results. Ronaldo submitted his own urine, which tested positive for methamphetamines, as they calculated that if one of them tested positive, it might reduce the authorities’ suspicion. The positive result mandated Ronaldo to parenting and “personal reconstruction” classes targeting emotional regulation and psychological issues. Without dismissing the importance of mental health, such individualistic approaches obscured the broader structural and social dimensions of their situation, instead blaming Ronaldo as an unfit parent requiring moral transformation.

Ronaldo could not think of any specific reasons for taking the photographs in his project, including the one of a broken bicycle (see Figure 6). Instead, his emotionally charged interview kept circling back to his daughter. Afterwards, the lead author was reminded of an earlier interview when he described selling his bike because his daughter was hungry; he needed his bike but he loved his daughter and would sacrifice anything for her. Such practices of hope provide a powerful counter-narrative to dominant portrayals of parents who use drugs as selfish and uncaring.

Figure 6.

Photograph by Ronaldo 2011.

Mildred and Ronaldo’s story reflects wider calls to discipline poor drug users for their “bad decisions” instead of acknowledging how the structural violence of the drug war constrains their ability to be “good parents” (Knight 2015). Were they unfit parents whose drug use rendered them as undeserving of having children? Should state authorities be empowered to decide if parents are suitable caretakers? For Mildred and Ronaldo, the “machinery of hopelessness” enacted by health care, child welfare, and law enforcement systems brought the drug war inside their private lives and undermined their future as a family. Despite their collusion in hopes of winning their daughter back, both partners said that her removal exacerbated their hopelessness and challenged any attempts at sobriety.

Dangerous safe havens

The hopelessness and hardships experienced by couples fed into their multiple years of drug use, which the punitive approach of the drug war fails to address. As we have argued elsewhere, shared experiences of marginalization and the search for acceptance by intimate partners who also struggled with drug use rendered couples’ relationships of critical material and emotional importance. Amidst the public tactics of the drug war, couples’ relationships formed “dangerous safe havens” from these threats (Syvertsen and Bazzi 2015). In forming these havens, couples engaged in shared acts of drug procurement, use, and withdrawal, acting in concert to help each other navigate their drug use and the adverse social conditions of their daily lives. In the process, injection-related risk behaviors such as syringe sharing represented emotional intimacy that virally endangered partners while socially sustaining their relationships.

Mariposa, 23, and Jorge, 29, were the youngest couple in our sample and their story illustrated such themes. Despite engagement in sexual relationships and drug use with outside partners, including Mariposa’s sex work that supported their drug use, the couple shared a close relationship that they qualitatively differentiated from their involvement with other people. The majority of their photographs were portraits of each other or depicted time spent together in the hotel room where they lived. In contrast to its location in the heart of the Zona Roja, the dangerous safe haven of their hotel room (see Figure 7) conveyed an innocent and child-like feel, including Mariposa’s favorite poster of Minnie Mouse, which she colored herself and personalized with a caption, Te Amo (“I love you”). Other photographs evidenced the playful nature of their relationship, and Jorge laughed especially deeply throughout his interview at the images they took of themselves getting high on methamphetamine and hamming it up for the camera. At another point, he stared deeply at a photograph of Mariposa and clenched his fist to his heart as he spoke about how much she meant to him.

Figure 7.

A couple’s “dangerous safe haven” in the Zona Roja. Many photographs taken by couples depicted the intimate spaces inside their homes. Photograph by Mariposa 2011.

Jorge and Mariposa originated from the interior of Mexico and found important forms of support and companionship in each other in their new city. They both said that drug use and other stigmatized behaviors were hidden in their home communities in comparison to the “fun and free” lifestyle and anonymity of Tijuana. Indeed, the drug war has reinforced the relaxed zones of transit and vice that have historically characterized liminal border spaces. Campbell (2010) has described the El Paso-Ciudad Juarez border as a fluid cultural space where identities could be regenerated and the value and meaning of drugs were constantly negotiated. For Mariposa, Jorge, and likely countless other young people in the border region, drug use, at least initially, represented imagined futures of freedom and escape from their socially conservative upbringing. Flourishing drug markets catering to young people seeking fun and danger have been documented in other dynamic border regions (Zoccatelli 2014) and counter monolithic narratives of depraved drug use requiring the heavy handed discipline of the drug war.

Jorge and Mariposa were content in their “outlaw love” (Bourgois and Schonberg 2009:73) and daily methamphetamine use. Nevertheless, vulnerability to arrest, incarceration, harassment, violence, and disease are real future possibilities as long as the drug war continues to rage outside the safe haven of their hotel room. In the meantime, the hope embedded in their relationship helped insulate them from such fears.

Hope amidst the horror of war

The daily lives and experiences that we documented among socially marginalized couples who live on the Mexico–USA border reveal some of the small forms of hope that emerge in response to a global drug war. While the punitive nature of the war and its “machinery of hopelessness” unleash severe forms of physical and structural violence that disproportionately affect marginalized populations of people who use drugs, the dominant and violent images circulating in the media obscure the full story. In their own ways and to varying degrees of prosperity, the couples in our study tried to create “lives worth living even in the midst of suffering” (Mattingly 2010:6). As couples navigated the harsh tactics of the drug war, their vulnerabilities became shared embodied experiences, subjectivities of sympathy and understanding for others with similar struggles, and in the context of intimate relationships, a conduit of strength, hope, and love. Ethnographic and visual methods lend powerful insight into these shared relationships with partners, family, and extended social networks to recast pejorative notions of co-dependency as communities of care that ensure mutual survival.

Our integrative critical and visual approach highlights that despite grandiose rhetoric celebrating the militaristic drug control tactics of an ongoing but failing drug war, poor and marginalized people who use drugs disproportionately suffer its multiple consequences. We do not wish to romanticize the lives of these couples or simply invert dominant media narratives of the “good” and “bad” sides of the story. Geraldo’s increased drug use and injection in public picaderos during Maria’s illness, Celia’s hectic apartment of canal refugees, Ronaldo and Mildred’s safe injection space that potentially exposed their daughter to drug use, and Jorge and Mariposa’s reveling in a youth of methamphetamine use, can all be interpreted in various ways. We highlight these experiences and practices of hope to share humanizing accounts of drug-using couples’ everyday lives that the dominant coverage of the drug war misses. We also acknowledge that like all anthropological endeavors, our interpretations of hope do not represent a singular truth. Rather, this work is one small version of war protest that we as ethnographers had unique access to tell.

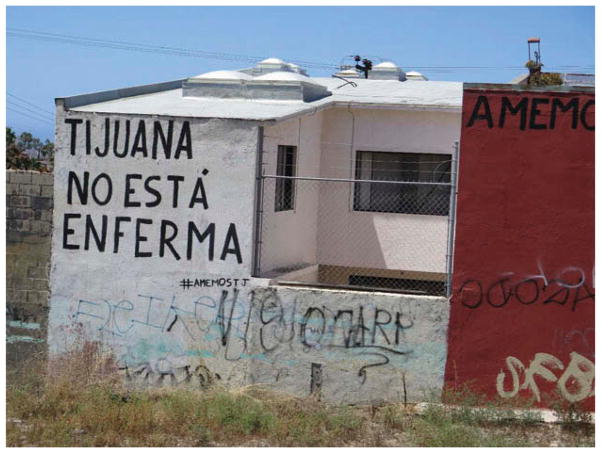

Postscript––Tijuana no está enferma

Despite uncertain relations with the US since its most recent presidential election and continued bouts of drug violence, Tijuana has been increasingly viewed as entering a period of “recovery” in which local industry and tourism are rebounding (Shirk 2014). Beyond such economic resilience, however, broader indications of hope beyond a drug war have appeared in multiple social spaces across the city (see Figure 8). We conclude by circling back to the sensationalistic media coverage of drug-related violence in Mexico to suggest that, just like the couples in our study, symbols and practices of hope permeate the city in subtle and public ways.

Figure 8.

“Tijuana is not sick;” #amemosTJ (#WeLoveTJ [Tijuana]). Counterpunching the threatening arcomensajes (warning messages left by drug cartels near crime scenes intending to terrorize the public; see Pérez, Pérez, and Pérez 2013), explicit “scenes of confrontation” across the city offer messages of hope amidst the failing drug war. Photograph by Jennifer Syvertsen 2015.

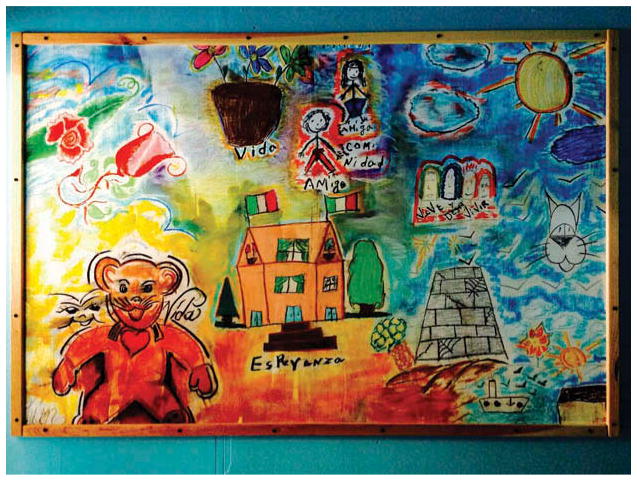

Several ongoing initiatives are also addressing drug use and the various health harms created by the drug war. Research engaging the Tijuana municipal police is testing a strategy to deliver HIV prevention education and training to active officers, including methods for interacting humanely with people who use drugs (Strathdee et al. 2015). The “Health Frontiers in Tijuana” (HFiT) clinic is a binational, student-run free clinic for underserved populations lacking access to routine medical care. This program also enables physicians and medical students to develop greater sensitivity to issues of drug use, homelessness, and other indicators of structural vulnerability (Ojeda et al. 2014). La Clínica de Heridas (the Wound Clinic) is another volunteer-run mobile clinic serving people who use drugs and suffer from injection-related wounds (abscesses). It reaches a wide population comprised largely of homeless migrants and US deportees who have been dispersed throughout Tijuana due to police victimization and violence (Mittal et al. 2016). People who inject drugs also engage in communal art projects, including a mural (see Figure 9) located inside a public health research office in the Zona Roja that provides an expressive venue for participants to enjoy.

Figure 9.

A mural created by people who inject drugs. Underneath the building, someone wrote “Esperanza,” or the Spanish word for “hope.” Plans are underway for future collaborative art projects to channel creativity and raise social consciousness about drug use along the border. Photograph by María Luisa Mittal 2015.

As a final note, these and numerous other initiatives in Tijuana require sustainable political and financial support and creative energy to continue to confront the deleterious drug war. While such individual efforts are significant and bring much needed hope, the drug war will nevertheless continue to ravage lives until governments on both sides of the border thoughtfully address the structural factors at its core. Recent calls to build a wall along the border are a dangerously simplistic policy proposal in a longer history of often contentious and uncertain bi-national relations. We call for a more humanistic approach to drug policy rather than continued reliance on political weaponry that disproportionately incarcerates, kills, and otherwise harms the most vulnerable among us. Through critical visual scholarship, our intent is to reveal structural violence while also highlighting the practices of care and forms of hope that emerge in its wake to further clarify why this drug war must end. A wall can be built, like a physical scar, but it will never completely sever communities or hope.

Acknowledgments

We would like to warmly thank the participants who shared their lives with us. Thanks to Liz Cartwright and Jerome Crowder for organizing the AAA panel where this article was originally presented and for providing valuable feedback on subsequent drafts. We also acknowledge Nancy Romero-Daza, David Himmelgreen, Liz Bird, Robin Pollini, Bryan Page, and Shana Hughes for their valuable insight and guidance on this project. Finally, we thank the helpful anonymous reviewers whose comments strengthened this article. Institutional review boards at the University of California, San Diego, The University of South Florida, and El Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana approved all study protocols.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants R01DA027772, R36DA032376, T32DA023356, P30AI060354, D43TW008633, R25TW009343, the University of South Florida Presidential Doctoral Fellowship, and the Boston University Peter Paul Career Development Professorship.

Biographies

Jennifer L. Syvertsen, PhD, MPH, is an assistant professor of anthropology at The Ohio State University. She received her PhD in medical anthropology and MPH in epidemiology from the University of South Florida and completed postdoctoral training in Global Public Health at the University of California, San Diego. Her work addresses health disparities, structural vulnerability, gender, and emotional well-being among socially marginalized populations most at risk for HIV.

Angela Robertson Bazzi, PhD, MPH, is an assistant professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the Boston University School of Public Health. She received her PhD in Global Health from the University of California, San Diego, and completed postdoctoral training at the Harvard School of Public Health. Her mixed methods research is focused on substance use, sexual health disparities, and the social determinants of infectious diseases among marginalized populations globally and in the United States.

María Luisa Mittal, MD, is a postdoctoral fellow at the Division of Global Public Health at UC San Diego, and an Adjunct Professor of Community Medicine at her alma mater Universidad Xochicalco in Tijuana, Mexico. Her research focuses on reducing harms associated with substance use worldwide, especially in the Mexico–USA border region. In collaboration with the Division of Global Public Health at the UCSD School of Medicine and the Mexico–USA Border Health Commission, her work has concentrated on HIV prevention with underserved, marginalized populations, including female sex workers and people who inject drugs in Tijuana, Mexico.

Footnotes

For an explanation of the parent study, see Syvertsen et al. (2012). Study protocol for the recruitment of female sex workers and their non-commercial partners into couple-based HIV research. BMC Public Health 12(1):136. For a photo blog discussing several analyses from the parent study, see http://ajphtalks.blogspot.com/2015/07/q-with-jennifer-syvertsen-of-ohio-state.html.

The final sample included six couples. One woman was given a camera, but was lost to follow-up before she returned it, so we excluded the couple from the study. One woman became seriously ill and was unable to participate in the photograph portion of the project, but her male partner was included. Each participant received one 27-exposure disposable camera, except that the first two women enrolled were given additional cameras for pilot testing. In total, we collected 301 images from 11 individuals. While we considered using smartphones or digital cameras, we opted for disposable cameras to reduce participants’ risk for theft or police violence.

One participant claimed to have witnessed someone get run over by a car and badly injured as he ran out of the canal to escape the police; she said she thought about taking photographs of the incident, but decided against it.

All names have been changed to protect identities.

This practice is no longer in place under universal health coverage in Mexico. Unfortunately, Mildred and Ronaldo’s daughter was born before Mexico’s national health insurance program, Seguro Popular, was introduced in 2003. Seguro Popular did not reach universal coverage until nine years after implementation. It is unknown how many drug-involved families are continuously marginalized by lack of access to health care services (Knaul et al. 2012).

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/gmea.

References

- Avni R. Mobilizing hope: Beyond the shame-based model in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. American Anthropologist. 2006;108(1):205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi AR, Syvertsen JL, Rolón ML, Martinez G, Rangel G, Vera A, Amaro H, et al. Social and structural challenges to drug cessation among couples in Northern Mexico: Implications for drug treatment in underserved communities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2016;61:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, Lozada R, Gaines T, Abramovitz D, Staines H, Vera A, Rangel G, et al. Syringe confiscation as an HIV risk factor: The public health implications of arbitrary policing in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Journal of Urban Health. 2013;90(2):284–298. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9741-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, Wagner KD, Arredondo J, Palinkas L, Magis Rodríguez C, Kalic N, Strathdee SA. Implementing Mexico’s “Narcomenudeo” drug law reform: A mixed methods assessment of early experiences among people who inject drugs. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2015;10(4):384–401. [Google Scholar]

- Biehl JG, Good B, Kleinman A. Subjectivity: Ethnographic Investigations. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boullosa C, Wallace M. A Narco History: How the United States and Mexico Jointly Created the “Mexican Drug War”. New York: OR Books; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. The moral economies of homeless heroin addicts: Confronting ethnography, HIV risk and everyday violence in San Francisco shooting encampments. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:2323–2351. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. Crack and the political economy of social suffering. Addiction Research and Theory. 2003;11:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Schonberg J. Righteous Dopefiend. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Lozada R, Cornelius WA, Firestone Cruz M, Magis-Rodríguez C, Zúñiga de Nuncio ML, Strathdee SA. Deportation along the US–Mexico Border: Its relation to drug use patterns and accessing care. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2009;11(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Strathdee SA, Magis-Rodríguez C, Bravo-García E, Gayet C, Patterson TL, Bertozzi SM, et al. Estimated numbers of men and women infected with HIV/AIDS in Tijuana, Mexico. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(2):299–307. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9027-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Case P, Ramos R, Magis-Rodriguez C, Bucardo J, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Trends in production, trafficking, and consumption of methamphetamine and cocaine in Mexico. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41(5):707–727. doi: 10.1080/10826080500411478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell H. Drug War Zone: Frontline Dispatches from the Streets of El Paso and Juarez. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clemens MA, Montenegro CE, Pritchett L. The place premium: Wage differences for identical workers across the US border (Working Paper No. RWP09-004) Boston, MA: Harvard Kennedy School; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Linton M. Tomorrow Is a Long Time: Tijuana’s Unchecked HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Hillsborough, NC: Daylight Books; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Crapanzano V. Reflections on hope as a category of social and psychological analysis. Cultural Anthropology. 2003;18(1):3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Csete J, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M, Altice F, Balicki M, Buxton J, Cepeda J, et al. Public health and international drug policy. The Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1427–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00619-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas TJ. Somatic modes of attention. Cultural Anthropology. 1993;8(2):135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais RR. Shelter Blues: Sanity and Selfhood among the Homeless. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Drug Policy Alliance. The Federal Drug Control Budget: New Rhetoric, Same Failed Drug War. New York: Drug Policy Alliance; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E. Anthropology and photography: A long history of knowledge and affect. Photographies. 2015;8(3):235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. Infections and Inequalities: The Modern Plagues. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A. The promise: On the morality of the marginal and the illicit. Ethos. 2014;42(1):51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A. Serenity: Violence, inequality, and recovery on the edge of Mexico City. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2015;29(4):455–472. doi: 10.1111/maq.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlee F, Hurley R. The war on drugs has failed: doctors should lead calls for drug policy reform. BMJ. 2016:355. http://idhdp.com/media/531191/bmj1.pdf.

- Graeber D. The Machinery of Hopelessness. Adbusters. 2009:82. https://www.adbusters.org/article/the-machinery-of-hopelessness/

- Guerrero J. Tijuana mandates drug treatment for hundreds Of homeless. KPBS. 2015 Apr 13; http://www.kpbs.org/news/2015/apr/13/tijuana-homeless-get-compulsory-treatment/

- Harper D. Talking about pictures: A case for photograph elicitation. Visual Studies. 2002;17(1):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. Spaces of Hope. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Heinle K, Molzahn C, Shirk DA. University of San Diego Department of Political Science & International Relations. San Diego, CA: University of San Diego; 2015. Drug Violence in Mexico: Data and Analysis through 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heinle K, Molzahn C, Shirk DA. Drug Violence in Mexico: Data and Analysis through 2015. University of San Diego Department of Political Science & International Relations; San Diego, CA: University of San Diego; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA. The War on Drugs III: The Continuing Saga of the Mysteries and Miseries of Intoxication, Addiction, Crime, and Public Policy. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. “Make sure somebody will survive from this:” Transformative practices of hope among Danish organ donor families. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2016;30(3):378–394. doi: 10.1111/maq.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsulis Y. Sex Work and the City: The Social Geography of Health and Safety in Tijuana, Mexico. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering and Healing and the Human Condition. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Kleinman J. The appeal of experience; the dismay of images: Cultural appropriations of suffering in our times. Daedalus. 1996;125(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Knaul FM, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantás O, García-Junco D, Arreola-Ornelas H, Barraza-Lloréns M, Sandoval R, et al. The quest for universal health coverage: achieving social protection for all in Mexico. The Lancet. 2012;380(9849):1259–1279. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight KR. Addicted Pregnant Poor. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly C. The Paradox of Hope: Journeys Through a Clinical Borderland. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal ML, González-Zúñiga P, Parish AJ, Lazos-Torres K, Rocha-Jiménez T, Arredondo J, Davidson P, et al. UCSD Public Health Research Day. La Jolla, CA: 2016. Apr 6, Building binational and interdisciplinary capacity for a sustainable mobile wound clinic for persons who inject drugs (PWID) in Tijuana, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Novas C. The political economy of hope: Patients’ organizations, science and biovalue. BioSocieties. 2006;1(3):289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda VD, Eppstein A, Lozada R, Vargas-Ojeda AC, Strathdee SA, Goodman D, Burgos JL. Establishing a binational student-run free-clinic in Tijuana, Mexico: A model for US–Mexico border states. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2014;16(3):546–548. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9769-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Alcázar I, Dyck I. Migrant narratives of health and well-being: Challenging ‘othering’ processes through photo-elicitation interviews. Critical Social Policy. 2012;32(1):106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez PLC, Pérez JGA, Jr, Pérez MCEC. Narco mensajes, inseguridad y violencia: Análisis heurístico sobre la realidad mexicana (Narco messages, insecurity and violence: Heuristic analysis about Mexican reality) Historia y Comunicación Social. 2013;18:839–853. [Google Scholar]

- Perry S, Marion JS. State of the ethics in visual anthropology. Visual Anthropology Review. 2010;26(2):96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Philbin M, Lozada R, Zuniga M, Mantsios A, Case P, Magis-Rodriguez C, Latkin C, et al. A qualitative assessment of stakeholder perceptions and socio-cultural influences on the acceptability of harm reduction programs in Tijuana, Mexico. Harm Reduction Journal. 2008;5(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-36. https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1477-7517-5-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pink S. The Future of Visual Anthropology: Engaging the Senses. New York: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Wagner KD, Strathdee SA, Shannon K, Davidson P, Bourgois P. Structural violence and structural vulnerability within the risk environment: Theoretical and methodological perspectives for a social epidemiology of HIV risk among injection drug users and sex workers. In: Campo PO, Dunn JR, editors. Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Towards a Science of Change. Paris: Springer-Verlag; 2011. pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Fitzgerald J. Visual data in addictions research: Seeing comes before words? Addiction Research & Theory. 2006;14(4):349–363. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AM, Garfein RS, Wagner KD, Mehta SR, Magis-Rodriguez C, Cuevas-Mota J, Gonzalez Moreno-Zuniga P, et al. Evaluating the impact of Mexico’s drug policy reforms on people who inject drugs in Tijuana, BC, Mexico, and San Diego, CA, United States: A binational mixed methods research agenda. Harm Reduction Journal. 2014;11:4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-11-4. https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1477-7517-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp E. Visualizing narcocultura: Violent media, the Mexican military’s Museum of Drugs, and transformative culture. Visual Anthropology Review. 2014;30(2):151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk DA. A tale of two Mexican border cities: The rise and decline of drug violence in Juárez and Tijuana. Journal of Borderlands Studies. 2014;29(4):481–502. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. Forging a political economy of AIDS. In: Singer M, editor. The Political Economy of AIDS. Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Company; 1998. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Page JB. The Social Value of Drug Addicts: Uses of the Useless. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. Of fish and goddesses: Using photo-elicitation with sex workers. Qualitative Research Journal. 2015;15(2):241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag S. On Photography. New York: Picador; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Stone LK. Suffering bodies and scenes of confrontation: The art and politics of representing structural violence. Visual Anthropology Review. 2015;31(2):177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Martinez G, Vera A, Rusch M, Nguyen L, Pollini RA, et al. Social and structural factors associated with HIV infection among female sex workers who inject drugs in the Mexico-US border region. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019048. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0019048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Arredondo J, Rocha T, Abramovitz D, Rolon ML, Mandujano EP, Rangel MG, et al. A police education programme to integrate occupational safety and HIV prevention: Protocol for a modified stepped-wedge study design with parallel prospective cohorts to assess behavioural outcomes. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008958. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008958. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/8/e008958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Magis-Rodriguez C, Mays VM, Jimenez R, Patterson TL. The emerging HIV epidemic on the Mexico-US border: An international case study characterizing the role of epidemiology in surveillance and response. Annals of Epidemiology. 2012;22(6):426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syvertsen JL, Bazzi AR. Sex work, heroin injection, and HIV risk in Tijuana: A love story. Anthropology of Consciousness. 2015;26(2):182–194. doi: 10.1111/anoc.12037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syvertsen JL, Robertson AM, Abramovitz D, Rangel MG, Martinez G, Patterson TL, Ulibarri MD, et al. Study protocol for the recruitment of female sex workers and their non-commercial partners into couple-based HIV research. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-136. http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-12-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb D. Is media coverage of the opioid crisis making it worse? Vice News. 2016 Oct 11; http://www.vice.com/en_ca/read/is-media-coverage-of-the-opioid-crisis-making-it-worse.

- Werb D, Mora ME, Beletsky L, Rafful C, Mackey T, Arredondo J, Strathdee SA. Mexico’s drug policy reform: Cutting edge success or crisis in the making? International Journal on Drug Policy. 2014;25(5):823–825. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccatelli G. “It was fun, it was dangerous”: Heroin, young urbanities and opening reforms in China’s borderlands. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2014;25(4):762–768. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]