Abstract

The migration and fate of cranial and vagal neural crest-derived progenitor cells (NCPCs) have been extensively studied; however, much less is known about sacral NCPCs particularly in regard to their distribution in the urogenital system. To construct a spatiotemporal map of NCPC migration pathways into the developing lower urinary tract, we utilized the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene to visualize NCPCs expressing Sox10. Our aim was to define the relationship of Sox10-expressing NCPCs relative to bladder innervation, smooth muscle differentiation, and vascularization through fetal development into adulthood. Sacral NCPC migration is a highly regimented, specifically timed process, with several potential regulatory mileposts. Neuronal differentiation occurs concomitantly with sacral NCPC migration, and neuronal cell bodies are present even before the pelvic ganglia coalesce. Sacral NCPCs reside within the pelvic ganglia anlagen through 13.5 days post coitum (dpc), after which they begin streaming into the bladder body in progressive waves. Smooth muscle differentiation and vascularization of the bladder initiate prior to innervation and appear to be independent processes. In adult bladder, the majority of Sox10+ cells express the glial marker S100β, consistent with Sox10 being a glial marker in other tissues. However, rare Sox10+ NCPCs are seen in close proximity to blood vessels and not all are S100β+, suggesting either glial heterogeneity or a potential nonglial role for Sox10+ cells along vasculature. Taken together, the developmental atlas of Sox10+ NCPC migration and distribution profile of these cells in adult bladder provided here will serve as a roadmap for future investigation in mouse models of lower urinary tract dysfunction.

Keywords: Sox10, sacral neural crest, lower urinary tract, pelvic ganglia, peripheral nervous system, autonomic nervous system, bladder

1. Introduction

Early in embryonic development, neural crest cells delaminate from the dorsal neural tube and migrate along prescribed paths to eventually differentiate into Schwann cells and glia, as well as peripheral neurons, melanocytes, chondrocytes, adrenal chromaffin cells and other cell lineages (Le Douarin et al., 2008; Shakova and Sommer, 2010). These migratory cells, termed neural crest-derived progenitor cells (NCPCs), express Sox10 and differentiate to form sensory and autonomic innervation for a variety of organs, including the lung, heart, kidney, and intestine (Freem et al., 2010; Itaranta et al., 2009; Lajiness et al., 2014; Lake and Heuckeroth, 2013; Musser and Southard-Smith, 2013; Obermayr et al., 2013; Verberne et al., 2000). Detailed spatiotemporal maps of neural crest derived innervation for these organs have been particularly informative for understanding disease processes. In contrast, surprisingly little is known at the cellular level about initial colonization of the lower urogenital tract (LUT) by Sox10+ NCPCs. Despite the fact that sacral NCPCs give rise to pelvic ganglia, which provide essential autonomic innervation to the LUT, the principal focus of prior sacral NC analysis has been the contribution of these progenitors to the enteric nervous system (Anderson et al., 2006; Kapur, 2000; Mundell et al., 2012).

A comprehensive understanding of LUT innervation and the factors that regulate this system have the potential to impact treatment and quality of life for patients who have sustained bladder damage. Injury to the bladder can result from a multitude of insults: congenital disorders, infection, trauma, cancer, or iatrogenic injury occurring during abdominopelvic surgery (Atala, 2011). Significant advances have been made in field of bladder repair using autologous patient cells to seed bladder scaffolds (Atala et al., 2006). However, efforts to innervate bladder scaffolds have not been successful (Lam Van Ba et al., 2015; Oberpenning et al., 1999). Thus, detailed understanding of the normal events that occur in development of LUT innervation may lead to strategies for regeneration of damaged or diseased neural inputs in the bladder.

We previously reported the distribution of neural elements in the fetal mouse urogenital tract (Wiese et al., 2012); however, much remains unknown about the initial stages when LUT innervation begins. Sacral NCPCs have been reported migrating around the distal hindgut on their way to the urogenital sinus as early as 11.5 days post coitus (dpc), and neuronal differentiation within pelvic ganglia is ongoing at 15.5 dpc (Anderson et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2011; Wiese et al., 2012). It has not yet been determined when autonomic pelvic ganglia first coalesce or when neurogenesis in these ganglia first initiates. Because regenerative strategies aimed at compensating for deficits of bladder innervation would benefit from understanding basic processes in the normal development of LUT nerves, we undertook a study of sacral NCPC migration during development of bladder innervation. Using our Sox10-Histone2BVenus (Sox10-H2BVenus) reporter strain (Corpening et al., 2011), we specifically examined when neuronal progenitors first enter the urogenital sinus mesenchyme that will become the primitive bladder, when markers of differentiating neurons and glia first appear within the structures of the LUT, and whether there are temporal variations in migration of NCPCs into the bladder that might suggest key regulatory stages. We concurrently documented the distribution of Sox10+ NCPCs in late fetal and adult bladders to establish a normal baseline that may prove informative in the analysis of mouse models of bladder dysfunction. Based on our initial observations of NCPC migration into the bladder and the potential interdependence between innervation and bladder muscle development and vascularization, we examined the distribution of NCPCs relative to the timeline of fetal smooth muscle and vascular development in the normal mouse bladder. We observed that the processes of innervation, vascularization and smooth muscle development appear to initiate independently of one another. Our initial survey of the distribution of Sox10+ cells in the adult bladder suggests heterogeneity of these cells within the bladder wall and sets the stage for future analysis of discrete neural crest-derived lineages in normal maturation and disease of the LUT.

2. Results

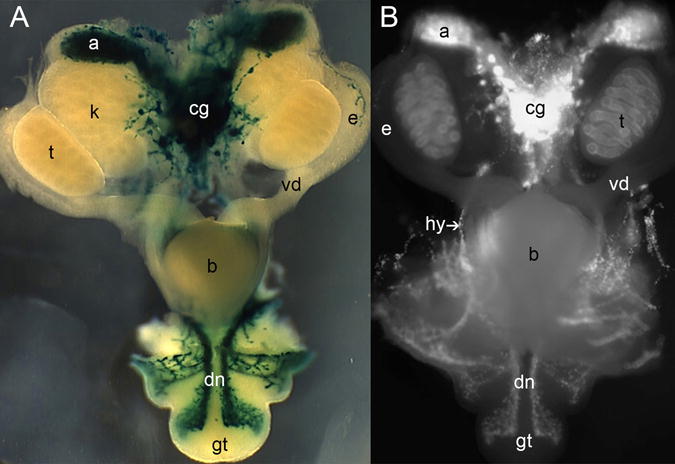

2.1 NCPCs that populate the urogenital tract are revealed by Sox10 expression

Initial studies characterizing the migration patterns of sacral NCPCs focused on progenitors expressing a dopamine beta-hydroxylase transgene (Dβh-nLacZ) and their differentiation as they approached the hindgut (Anderson et al., 2006; Kapur, 2000; Wang et al., 2011). While those studies identified Dβh+ cells within pelvic ganglia by 13 dpc, more comprehensive labeling of NCPCs would be advantageous for visualizing migration patterns throughout the developing genitourinary system. To assess the feasibility of using a Sox10 transgenic reporter for detection and characterization of NCPCs in the genitourinary system, we compared the expression pattern of our previously described transgenic line Sox10-H2BVenus to that of a knock-in allele for Sox10 that expresses LacZ (Sox10LacZ-KO/+)(Britsch et al., 2001). The Sox10-H2BVenus transgene line faithfully recapitulates Sox10 expression in rostral neural crest populations, including cranial ganglia, otic vesicles, branchial arches, dorsal root ganglia, cervical ganglia, and vagal enteric neural crest (Corpening et al., 2011). Thus, we expected transgene expression patterns to mirror endogenous Sox10 among sacral NCPC as well. Intact genitourinary tissues were micro-dissected from Sox10LacZ-KO/+ and Sox10-H2BVenus embryos at 14–14.5 dpc and either stained for LacZ activity or imaged for fluorescence of the Sox10-H2BVenus reporter in whole mount (Fig. 1). Nearly identical expression patterns were observed, with strong expression in the adrenal glands, celiac ganglia, and numerous nerves tracts of both Sox10LacZ-KO/+ and Sox10-H2BVenus tissues. The consistency between expression of Sox10LacZ-KO/+ and Sox10-H2BVenus in the genitourinary tract extends prior studies that demonstrated that the 28O11 BAC backbone used to drive heterologous transgene reporters recapitulates expression of the endogenous Sox10 gene (Corpening et al., 2011; Deal et al., 2006). While the majority of expression sites were comparable between the two Sox10 lines, one difference we observed was the presence of Sox10-H2BVenus signal in the Sertoli cells of the testes. Sox10 has previously been identified in Sertoli cells (Harding et al., 2011; Polanco et al., 2010); however, no comparable LacZ staining was seen in Sox10LacZ-KO/+ testes. While this discrepancy may result from the testes being impermeable to LacZ staining, it is more likely due to loss of essential regulatory elements required to drive testes-specific expression in the Sox10LacZ-KO/+ line. Multiple intronic enhancers have been identified for Sox10 and the Sox10LacZ-KO/+ allele deletes sequences from introns 3 through exon 5 as a result of LacZ reporter integration (Betancur et al., 2010; Betancur et al., 2011; Britsch et al., 2001). In contrast, all intronic regulatory domains are retained in the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene, and animals expressing this reporter are phenotypically normal because the transgene does not alter the endogenous Sox10 locus. Because the Sox10-H2BVenus reporter illuminates normally developing NCPCs, we used this line to assess migration of sacral NCPCs in the developing LUT.

Figure 1. Distribution of sacral neural crest-derived progenitor cells (NCPCs) in and Sox10-H2BVenus embryos.

Ventral views of micro-dissected urogenital tracts are shown in whole mount from (A) a 14.5 dpc Sox10LacZ-KO/+ and (B) a 14.5 dpc Sox10-H2BVenus embryo (70× magnification). The superior (anterior) surface of the genital tubercle is shown. Abbreviations: a, adrenal gland; b, bladder; cg, celiac ganglia; dn, dorsal nerve; e, epididymis; gt, genital tubercle; hg, hindgut; k, kidney; t, testis; vd, vas deferens.

2.2 Sox10+ progenitors populate the developing urogenital tract mesenchyme by 11 dpc

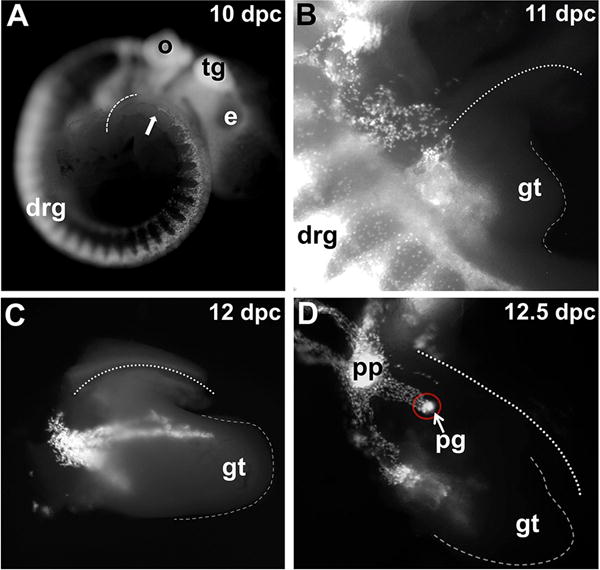

Using the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene reporter, we first examined early migration patterns of sacral NCPCs in whole mount tissues. At 10 dpc, it is apparent that sacral NCPCs, which arise at the level of somite 28 and posterior, have not yet delaminated from the dorsal neural tube (Fig. 2A, arrow). A day later at 11 dpc sacral NCPCs have migrated laterally and ventrally, coalescing as a loose stream of cells prior to migration towards the urogenital sinus mesenchyme and the genital tubercle (Fig. 2B). At 12 dpc in lateral whole mount views, the relationship of the forming bladder atop the genital tubercle, which is becoming innervated, is evident (Fig. 2C). At this stage, long streams of NCPCs have migrated nearly the entire length of the genital tubercle, remaining close to its dorsal (superior) surface and delineate the developing dorsal nerve. In addition, a second population of NCPCs have traveled caudally toward the ventral (inferior) aspect of the genital tubercle (Fig. 2C, see also Fig. 5). By 12.5 dpc, a definitive pelvic ganglion is visible proximal to the genital tubercle, just at the point of detachment from the remainder of the embryo. At this stage the contribution of the more dorsally situated pelvic plexus to the pelvic ganglion is evident in lateral whole mount views (Fig. 2D). In turn, the pelvic plexus is populated by NCPCs traveling along nerves coming from the dorsal root ganglia.

Figure 2. Initial migration of sacral NCPCs towards the the developing urogenital tract viewed in whole mount Sox10-H2BVenus embryos.

(A) Lateral view of a 10 dpc embryo imaged for H2BVenus fluorescence. The dorsal surface of the tail is outlined with a dashed line, and the most caudal neural crest cells are visible as punctate spots that are just emerging from the neural tube at the level of the hindlimb and are marked with an arrow. (B) Fluorescence image of H2BVenus-expressing NCPC entering the genital tubercle and pelvic mesenchyme of a 11 dpc embryo at the lumbosacral level (53× magnification). (C) Sox10-H2BVenus+ progenitors are visible in this lateral view of a micro-dissected lower urinary tract. The bladder is located above the genital tubercle and out of view behind the umbilical blood vessel in a 12 dpc embryo (50× magnification). (D) Lateral view of the urogenital system micro-dissected from a 12.5 dpc embryo shows Sox10+ NCPC migrating through the the pelvic plexus, prominent aggregation of cells within the pelvic ganglia anlagen (red circle), and migration of sacral NCPCs into the genital tubercle. The dashed line indicates the distal aspect of the genital tubercle. The dotted lines in (B), (C) and (D) denote the paths of umbilical blood vessels that flank the bladder. Abbreviations: e, eye; tg, trigeminal ganglion; o, otic vesicle; drg, dorsal root ganglia; gt, genital tubercle; pg, pelvic ganglion; pp, pelvic plexus.

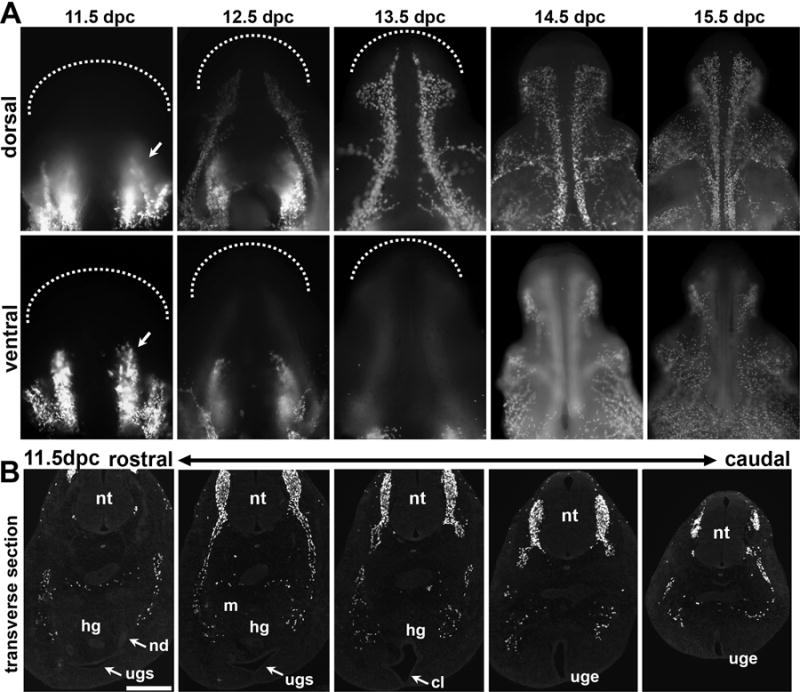

Figure 5. Stereotypical patterns of Sox10+ sacral NCPC migration throughout the developing genital tubercle.

(A) Wholemount Images of the dorsal (superior) surfaces of micro-dissected genital tubercle from Sox10-H2BVenus embryos at each developmental time point from 11.5 through 15.5 dpc are shown across the top row with ventral (inferior) surfaces shown immediately below. Arrows in panels for 11.5 dpc wholemount images indicate the position of ventral columnar aggregates that are pronounced at 11.5dpc and dissipate by 13.5 dpc. Dashed lines delineate the distal tip of the genital tubercle. (100×–150× magnification) (B) Fluorescent images of transverse sections through the caudal aspect of the sacral embryo show the relative locations of Sox10-H2BVenus+ NCPC that migrate around the metanephric mesenchyme (m) towards the urogenital sinus (ugs) in more rostral sections (right). Dispersed groups of Sox10+ cells at 11.5 dpc have not yet reached the flanks of the forming cloaca where the pelvic ganglia will form (middle). In more caudal sections (left) streams of H2BVenus+ cells are visible within the genital tubercle as it extends from the body wall marked by the urogenital epithelium (uge) at the midline. Individual sections are 18 microns with the entire span from the most rostral section to the most caudal section totaling approximately 550 microns. Scale bar = 200 microns.

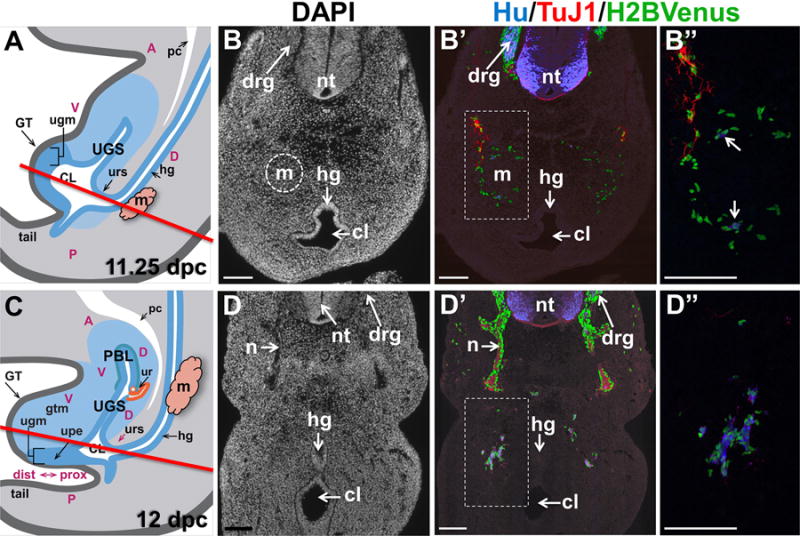

In our efforts to define migration patterns of sacral NCPCs into the LUT, we examined transverse sections stained with the pan-neuronal markers Hu-C/D (King et al., 1999), which labels cell bodies, and TuJ1, which labels neuronal processes, to determine when NCPCs initiate neuronal differentiation relative to when the pelvic ganglia coalesce within the urogenital sinus mesenchyme. At 11.25 dpc we observed that lumbosacral NCPCs migrating towards the urogenital sinus have reached and nearly surrounded the condensing metanephric mesenchyme, including the entire lateral aspect, but do not appear to enter the mesenchyme (Fig. 3A–B″). This distribution is consistent with a prior report that described migration of 10.5 dpc lumbosacral NCPCs ventrally between the lateral neural tube and somites towards the dorsal aspect of the metanephric mesenchyme (Itaranta et al., 2009). Even at this early stage of development, rare HuC/D+ neuronal cell bodies and TuJ1+ neuronal fibers are already admixed with Sox10+ cells, indicating that neuronal differentiation occurs as NCPCs are migrating toward the urogenital sinus and prior to aggregation of pelvic ganglia (Fig. 3A–A″).

Figure 3. Sacral NCPCs route around the metanephric mesenchyme and form loose aggregates in the pelvic ganglia anlagen by 12 dpc.

(A) Schematic diagram through the mid-sagital fetal LUT at 11.25 dpc illustrates the location of structures in the developing urogenital sinus. The metanephric mesenchyme is lateral to the midline (pink). A red line indicates the level of the plane of sections collected through the developing embryo that are shown in panel B. (B) Transverse cryosection through an 11.25 dpc Sox10-H2BVenus embryo at the level of the hindlimb stained with DAPI shows the anatomy of the metanephric mesenchyme (dashed circle) and the junction of the cloacal cavity with the hindgut. (B′) Immunostaining of the section in panel A with antibodies for HuC/D (neuronal cell bodies, blue) and TuJ1 (neuronal processes, red) shows the relative position of migrating Sox10-H2BVenus+ NCPC (green) (100× magnification). (B″) High magnification image (200×) of boxed area in A″ shows HuC/D+ cells emphasized by arrows. (C) Schematic diagram through the mid-sagital fetal LUT at 12 dpc illustrates the position of the forming primitive bladder and the rise of the metanephric mesenchyme (pink) relative to the hindgut. A red line indicates the plane of section shown in panel D. (D). Transverse cryosection through the sacral region of a 12 dpc Sox10-H2BVenus embryo at an axial level comparable to that shown in panel A. DAPI stain at this stage shows extension of nerve tracts from the neural tube and septation of the hindgut and cloaca. (D′) Immunostaining of the section in panel B with anti-HuC/D and TuJ1 antibodies reveals aggregates of NCPC co-mingled with HuC/D+ cells that are differentiating neurons (100× magnification). (D″) Magnification (200×) of boxed area in panel B′. Abbreviations: A, anterior; CL, cloaca; D, dorsal; drg, dorsal root ganglia; GT, genital tubercle; gtm, genital tubercle mesenchyme; hg, hindgut; m, metanephric mesenchyme; n, nerve tract; nt neural tube; P, posterior; PBL, primitive bladder; pc, peritoneal cavity; ugm, urogenital membrane; UGS, urogenital sinus; upe, urethral plate epithelium; ur, ureter; urs, urorectal septum, V, ventral. Scale bars = 100 microns. Schematic diagrams in Panels A and C were modified from Georgas et al., 2015.

Less than one day later in development, at 12 dpc, the embryo has elongated and the metanephric mesenchyme has ascended from the distal end of the hindgut upwards. As a result there is no longer any obstacle to NCPC migration toward the urogenital sinus mesenchyme. In sections collected at an anatomic level that transects the embryo just above the point of septation of the cloaca from the hindgut, Sox10+NCPCs are visible in loose aggregates dorsolateral to the cloaca, admixed with TuJ1+ nerve bundles (Fig. 3B–B″). Within these dorsolateral aggregates, NCPC-derived cells have undergone neuronal differentiation so that they have down-regulated the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene and exhibit expression of pan-neuronal markers (HuC/D and TuJ1) (Fig. 3B″).

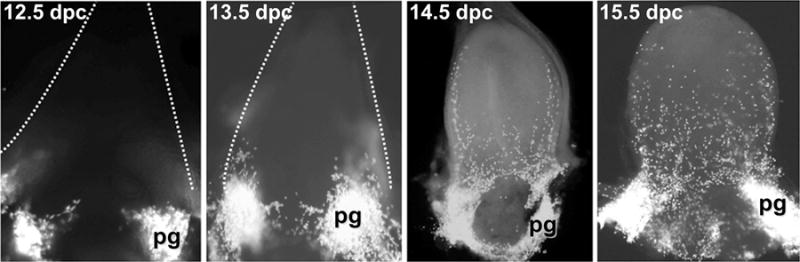

2.3 Colonization of the developing bladder and genital tubercle by Sox10+ progenitor cells is temporally and spatially orchestrated

When viewed in whole-mount from an anterior perspective looking down on the bladder flanked by the umbilical blood vessels, the coalescing pelvic ganglia are much more readily visible as bright clusters of Sox10+ cells than in any single transverse histologic section. At 12 dpc, Sox10+ NCPCs are aggregated in clusters bilaterally at the base of the developing bladder, but no migration into the bladder has begun (Fig. 4). Condensation of ganglia cells continues through 13 dpc with increasing numbers of Sox10+ NCPCs becoming more evident in the pelvic ganglia anlagen and little migration away from the ganglion core. By 14 dpc, the pelvic ganglion has increased markedly in size and wraps around the dorsal aspect of the urethra behind the bladder base and extends posteriorly along the urethra. Most notably at 14 dpc individual Sox10+ NCPCs have begun migrating out from the pelvic ganglia in pronounced streams along the lateral walls of the bladder and have nearly reached the bladder dome. At this stage there is minimal migration of NCPCs into the medial bladder body. By 15 dpc, many more NCPCs are evident in the bladder body due to a secondary wave of migration that populates the center of the bladder and produces a more uniform distribution of Sox10+NCPC in the medial region. However, at this point in development the bladder dome, near the urachus, is still sparsely populated by NCPCs. The consistent restriction of NCPCs within the anlagen of the pelvic ganglia from 12 dpc, when Sox10+ progenitors initially arrive, until 14dpc suggests this region may contain regulatory cues and function as a temporary “stop” along the path of NCPC migration into the bladder.

Figure 4. Sacral NCPC populate the primitive bladder by migration from the pelvic ganglia out into the bladder body.

Fetal bladder tissue micro-dissected from 12.5 dpc to 15.5 dpc Sox10-H2BVenus embryos was laid flat and imaged by fluorescent stereomicroscopy from the anterior aspect (4×–10× magnification). NCPC are labeled by bright fluorescence of the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene in the pelvic ganglia anlagen and visible as individual discrete cells that migrate out into the bladder body by 14.5 dpc due to nuclear localization of the H2BVenus reporter. Dashed lines delineate the blood vessels flanking the urogenital sinus/bladder at 12.5 and 13.5 dpc. The bladder dome is apparent in the 14.5 dpc and 15.5 dpc bladders.

A consistently orchestrated pattern of NCPC migration throughout the developing genital tubercle is likewise observed. At 11.5 dpc pronounced columnar aggregates of NCPC are visible in the dorsal aspect of the genital tubercle (Fig 5, top row). Transverse sections collected from the top of the urogenital sinus through the posterior aspect of the genital tubercle show these NCPCs flank the urogenital epithelium of the genital tubercle (Fig. 5B) but have not yet populated the location of the pelvic ganglia where the cloaca and hindgut septate. One day later at 12.5 dpc bilateral “streams” of NCPCs migrate laterally and distally along nearly the entire dorsal length of the genital tubercle (Fig. 5, top row). These two tracts are consistent with the location of the dorsal nerve of the penis/clitoris at maturity. By 13.5 dpc the dorsal tracts have shifted to a more medial location in the dorsal aspect of the genital tubercle and extend in parallel down to the distal tip that will eventually form the glans (Georgas et al., 2015). Foci of lateral migration are initiated at the distal tip and midshaft of the genital tubercle, resulting in a diaphanous, web-like distribution of NCPCs that wrap around the genital tubercle from the dorsal to ventral surfaces by 14.5 dpc and 15.5 dpc. On the ventral surface of the genital tubercle, columnar aggregates of NCPCs, which are so apparent at 11.5 dpc, appear to completely dissipate from the area of labioscrotal swelling by 13.5 dpc as cells migrate around from the dorsal surface to surround the swelling (Fig. 5, bottom row, compare arrows at 11.5, 12.5, and 13.5 dpc). The fate of these cells remains unclear and open to speculation. It is unlikely, however, that they undergo cell death, as fragmentation of the nuclear H2BVenus signal characteristic of apoptosis is not evident (Corpening et al., 2011).

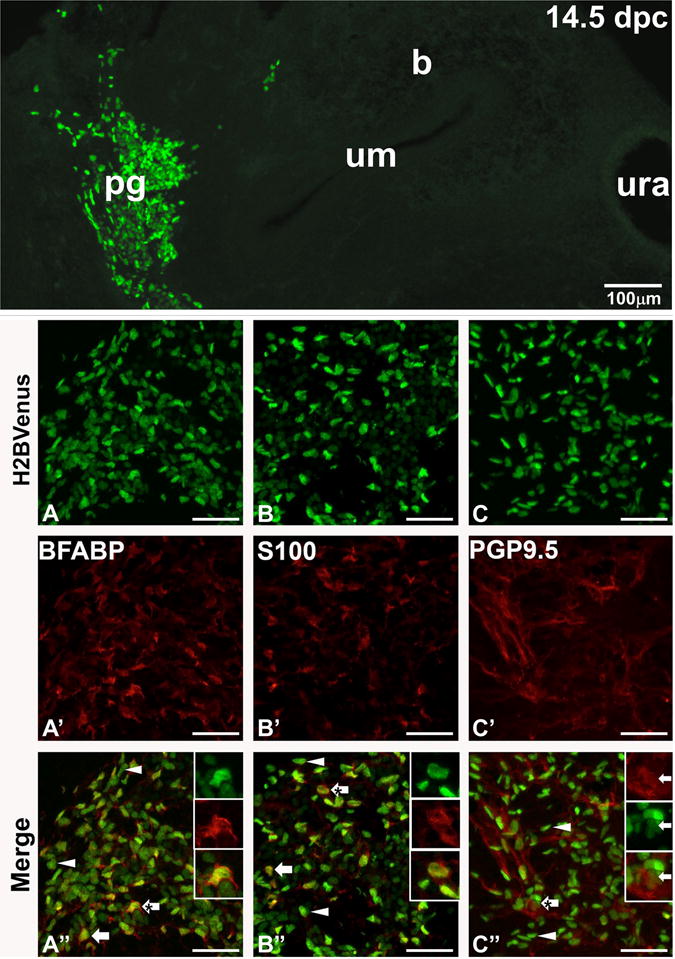

2.3 Sox10+ NCPCs undergo differentiation within the pelvic ganglia by 14 dpc

Previously we determined that neurogenesis is well along in the pelvic ganglia by 15.5 dpc, with HuC/D+/Phox2b+ neurons evident in large numbers (Wiese et al., 2012); however it has not been clear when gliogenesis occurs in the ganglia. To assess the appearance and distribution of peripheral glia relative to Sox10+ NCPCs, we undertook immunohistochemical analysis in cryosections at 14.5 dpc using the glial markers BFABP and S100β. By this stage the pelvic ganglia are highly condensed and visible as large clusters in sagittal sections (Fig. 6, top panel). BFABP is expressed in many glial cells and is the earliest glial marker detected during differentiation of NCPCs in the enteric nervous system (Young et al., 2003). Similarly, at 14.5 dpc within the pelvic ganglia there is readily visible colocalization of the early glial marker BFABP with Sox10+ cells marked by H2BVenus expression (Fig. 6, first column). Of H2BVenus+ cells within pelvic ganglia sections at 14.5 dpc 19 ± 2% exhibit strong co-localization of BFABP (n=5 ganglia sections, 2804 total cells counted). At this stage of development, co-localization with the glial marker S100β, which appears later in the progression of peripheral glial cell differentiation, is also visible in a subset of Sox10+ NCPC (Fig. 6, second column). Sox10+ NCPC exhibited coincident expression of S100β, in 15 ± 2% of pelvic ganglia cells at 14.5 dpc (n=5 pelvic ganglia sections, 4889 total cells counted). Concurrent with the initiation of gliogenesis, the Sox10 transgene down-regulates in the majority of differentiating pelvic ganglia neurons marked by PGP9.5; however, there are some cells that exhibit weak perdurance of the H2BVenus signal that overlaps with PGP9.5 expression. We counted H2BVenus+ cells that showed coincident expression of PGP9.5 and observed that 6 + 2% of differentiating neurons exhibited residual low intensity expression of the transgene (n=5 pelvic ganglia sections, 4701 total cells counted). These observations largely agree with lineage divergence of neurons and glia in the enteric nervous system, where Sox10 expression marks migrating progenitors that populate the intestine and is maintained in enteric glial cells but is extinguished when NCPCs undergo neuronal differentiation (Anderson et al., 2006; Young et al., 2003).

Figure 6. Neuronal-glial lineage divergence is ongoing within the pelvic ganglia at 14.5 dpc.

The relative size and position of a fetal pelvic ganglia in relation to the urinary bladder is shown in a cryosection (top, 100× magnification), where Sox10+ NCPC are labeled by intense H2BVenus expression. Below confocal images of cryosections immunostained with antibodies against BFAPF (red, early glial marker, left column panels) identify Sox10-H2BVenus+ cells (green, A) that exhibit co-localization in merged images (arrows, A″). There are some Sox10+ nuclei that do not show any BFABP co-localization (arrowheads, A″). At 14.5 dpc fewer Sox10-H2BVenus+ show co-localization with the more mature marker of peripheral glial S100b (red, middle column panels, B–B″) in cryosections stained for this antigen (arrows, B′), while most H2BVenus+ cells show no S100b labeling (arrowheads, B″). In contrast, confocal images of pelvic ganglia stained for PGP9.5 (red, neuronal marker, right column panels C – C″) reveal limited co-localization with this marker due to residual perdurance of the Sox10-H2BVenus+ transgene in cells that have progressed towards the neuronal lineage (arrows, C′), while there are many Sox10-H2BVenus+ cells that show no co-localization with PGP9.5 (arrowheads, C″). Confocal magnification is 400× for all images. High magnification insets to illustrate co-localization are show in the upper right of panels A″, B″, and C″. Abbreviations: b, bladder; pg, pelvic ganglia, um, urothelium; ura, urachus. Scale bars in panels A–C″ = 50 microns.

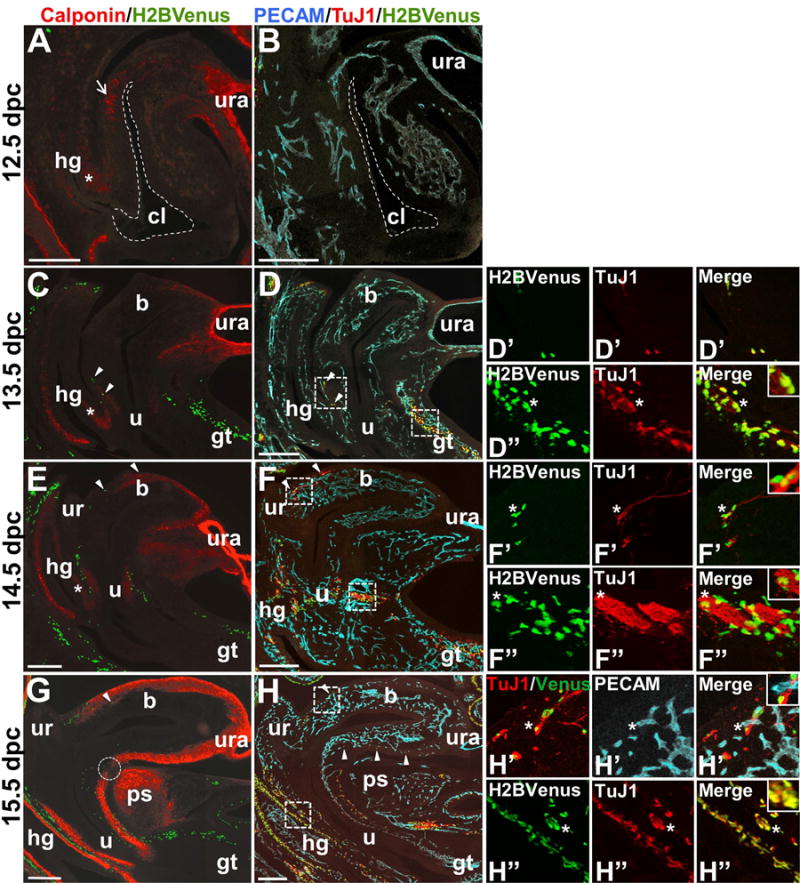

2.4. Smooth muscle differentiation, vascularization, and innervation of the developing LUT appear to be concurrent but spatially independent processes

In order to assess the colonization of the bladder body by NCPCs relative to differentiation of smooth muscle, we performed immunohistochemical labeling for calponin, which exclusively labels smooth muscle cells, in contrast to smooth muscle actin, which is also expressed in other cell types (Duband et al., 1993). At 12.5 dpc, the urachus is strongly positive for calponin and multiple foci of immunoreactive smooth muscle cells are observed within the pericloacal mesenchyme nearest the hindgut that will become the dorsal aspect of the bladder (Fig. 7). We were surprised to observe this regional initiation of calponin expression in one side of the primitive bladder instead of uniform appearance of calponin+ cells around the bladder circumference. Smooth muscle differentiation is also detected by calponin immunoreactivity in the distal end of the hindgut at the entrance to the cloaca. This was unexpected given that differentiation of the bowel occurs in a proximal to distal wave and that more proximal hindgut regions visible on the same sections show little, if any, calponin staining at this stage. One day later in development at 13 dpc, smooth muscle differentiation marked by calponin expression is still most prominent closest to the urachus and continues to extend dorsally from the bladder dome toward the bladder neck. At this stage, no smooth muscle is evident at the dorsal most aspect of the bladder neck where the ureters will eventually insert into the bladder wall. In contrast, smooth muscle is apparent in the urethra at 13 dpc and is spatially separated from smooth muscle differentiation in the bladder body. These two domains of smooth muscle differentiation in the urethra and bladder body continue to express higher levels of calponin in parallel and converge at the bladder neck at 15 dpc but remain separated by a small isthmus of non-reactive mesenchyme.

Figure 7. Temporal and spatial independence of sacral NCPC migration marked by Sox10-H2BVenus expression relative to smooth muscle and vasculature development in the bladder wall.

Images of sagittal cryosections through the developing lower urogenital tract of 12.5 dpc through 15.5 dpc Sox10-H2BVenus+ embryos are shown. Sox10-expressing NCPCs are visible as a result of H2BVenus transgene fluorescence (green) in sections immunostained either for calponin (red, panels A, C, E, G) to detect smooth muscle alone or jointly immunostained for PECAM (blue, endothelial cells) and TuJ1 (red, neuronal processes) in panels B, D, F, H. In all images, the ventral aspect of the embryo is on the right. Cryosections immunostained for PECAM and TuJ1 were approximately 160um lateral to the midsagittal sections used to detect calponin. For this reason, some midline structures are not visible in the sections used for PECAM/TuJ1 detection. All fluorescent (calponin) and confocal (PECAM/TuJ1) images were taken at 100× magnification and tiled in Adobe Photoshop to generate the composite images shown. An asterisk indicates the position of the extending urorectal septum that separates the hindgut from the cloaca (dashed outline, panels A, B) where smooth muscle differentiation marked by calponin immunoreactivity appears initially. A dotted circle emphasizes a gap in the continuity of calponin staining at the junction between the bladder neck and urethra at 15.5 dpc. Arrowheads indicate the locations of individual Sox10+ NCPCs that are integral to the urethral and bladder walls. High magnification insets in the rightmost column coincide with boxed insets in panels D, F, and H. At 13.5 dpc Abbreviations: b, bladder; cl, cloaca (dashed outline); gt, genital tubercle; hg, hindgut; ps, developing pubic symphysis; u, urethra; ur, ureter; ura, urachus. Scale bars = 200 microns.

At the earliest stages when smooth muscle differentiation is ongoing in the LUT, NCPCs have not yet entered the bladder body and remain in the pelvic ganglia anlagen. At 12 dpc, as shown in Figure 7, the bladder and genital tubercle are devoid of NCPCs and any TuJ1+ nerve processes. By 13.5 dpc infrequent NCPCs, marked by nuclear H2BVenus, are detected in the dorsal aspect of the urethra and are observed in large numbers along the dorsal surface of the genital tubercle where innervation by the pudendal nerve occurs. While NCPCs appear sparse in 14 dpc mid-sagittal sections that reveal the anatomic structures of the developing LUT, they are present in greater numbers than at 13dpc in the dorsal urethra and have also invaded the smooth muscle of the ventral urethra. Even greater numbers of NCPCs are observed in more lateral areas of the bladder within sections collected further away from the midline, consistent with the higher density of NCPCs in the lateral bladder walls that are evident in the whole mount images of Figure 4 (data not shown). At 13.5 dpc many Sox10+ NCPCs colocalize with the neuronal marker TuJ1, while fewer show colocalization at 14.5 dpc, suggesting that NCPC migration and neuronal differentiation occur simultaneously (Fig. 7). By 15 dpc NCPCs are visible in mid-sagittal sections along both the dorsal and ventral aspects of the bladder, within the smooth muscle and submucosa of the urethra, and in large numbers along the length of the genital tubercle. By 15 dpc, Sox10-H2BVenus and TuJ1 generally label distinct populations of cells surrounding the bladder neck, migrating through the posterior bladder wall, and extending down the genital tubercle. Colocalization of H2BVenus with TuJ1 is still present at these later time points in the LUT, but is not as prominent. By comparison, colocalization of Sox10-H2BVenus with TuJ1 is still prominent in the fetal hindgut at 15.5 dpc.

Because close associations between NCPC-derived enteric ganglia and capillaries have been observed, it has been proposed that development of peripheral nerves and vasculature may be coordinated (Fu et al., 2013). To investigate this, we applied the endothelial cell marker PECAM to visualize formation of blood vessels relative to migration of NCPC into the LUT. Numerous PECAM+ endothelial cells condensing into vasculature tubes are evident in the LUT as early as 12.5 dpc, despite the near absence of smooth muscle differentiation and total absence of innervation at this stage (Fig. 7B). Nascent vasculature develops throughout the entire LUT in a fairly uniform manner, in contrast to the dorsal to ventral migration of NCPCs into this system. Not until 15 dpc did we observe intimate association of Sox10-H2BVenus+ cells with forming PECAM+ endothelial cells, most notably in the developing urethra (Fig. 7H). Most likely these Sox10-H2BVenus+ NCPC are differentiating glia, as they are closely juxtaposed with TuJ1+ processes. Despite extensive formation of PECAM+ vasculature from 12–15 dpc in the bladder, urethra, and hindgut, we noted that the epithelium and its immediate underlying mesenchyme in these tissues is completely devoid of vascularization at these stages. Our analysis of markers for innervation, smooth muscle differentiation, and vascularization shows that these processes do not proceed concurrently in the developing LUT.

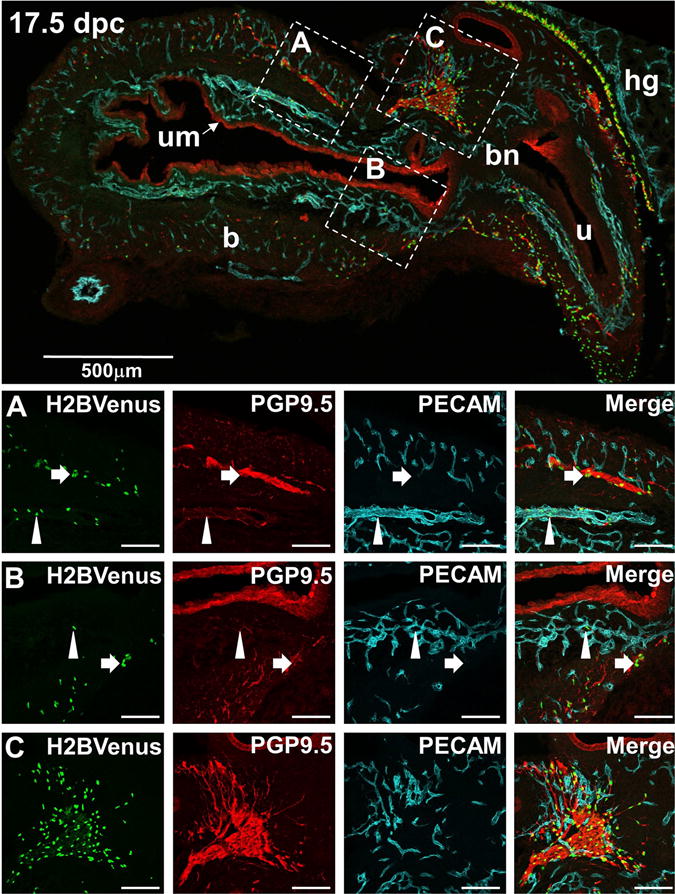

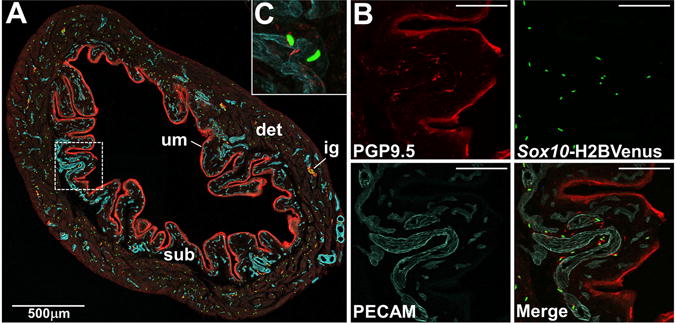

2.5. In late fetal development and adult bladder, Sox10+ sacral NC-derivatives primarily associate with neuronal processes, but a subpopulation are intimately associated with vascular endothelium

By 17.5 dpc, Sox10-H2BVenus cells are distributed extensively throughout the LUT, and we investigated the spatial relationship of those cells to the PGP9.5+ neurons and PECAM+ vasculature within the bladder wall (Fig. 8, top). In contrast to exclusion of endothelial cells from the epithelium that is apparent at 15 dpc, by 17.5 dpc the developing vasculature is widely dispersed throughout the detrusor muscle and is now prominent within the submucosa. Use of PGP9.5 as a neuronal marker, instead of TuJ1, also produces characteristic staining of urothelium in the bladder, which highlights the intimate contact of the vasculature with the basal surface of the urothelium. Other investigators have detected PGP9.5 in the urothelium and a knock-in allele of Uchl1 (Uchl1tm1Dgen) also has been reported in the urothelium(Georgas et al., 2015; Wiese et al., 2013), however this expression does not show co-localization with other neuronal markers like HuC/D or TuJ1 and is clearly non-neuronal.

Figure 8. Association of NCPCs with both neuronal processes and blood vessels in the 17.5 dpc developing bladder.

The top panel shows a low-magnification (70×) midsagittal view of an E17.5 bladder from an Sox10-H2BVenus (green) fetal mouse immunostained with the neuronal marker PGP9.5 (red) and the endothelial marker PECAM (blue). Images in Rows A, B, and C are higher magnification views (200×) of the corresponding areas delineated by dashed squares in the top panel. Typical Sox10-H2BVenus+ glial cells intimately associated with neuronal processes are highlighted by arrows in Rows A and B. Rare Sox10+ cells closely associated with vascular endothelium and distant from neuronal processes are highlighted by arrowheads in Row A and B. A high density of Sox10+ cells, neuronal processes, and vascular endothelium is present within the pelvic ganglion shown in Row C. This tight aggregate of cells precludes an assessment of whether a subpopulation of Sox10+ cells associates more closely with endothelial cells than with neuronal processes. The staining of urothelium with PGP9.5 antibody is consistently observed by many laboratories (See www.gudmap.org Gene Expression Database).

Throughout the bladder wall, the majority of Sox10+ cells are tightly associated with neuronal processes by 17.5 dpc and no longer show any co-localization with neuronal markers like TuJ1+ and PGP9.5 (Fig. 8, Rows A and B, arrows). Interestingly, we observed rare Sox10+ NCPCs in close proximity to the vascular endothelium, at a distance from neurons and neuronal processes (Fig. 8, Rows A and B, arrowheads). At this same stage, the pelvic ganglia are composed of tight aggregates of cells of multiple lineages, including glia, neurons, and vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 8, Row C). Due to the density of ganglia cells at 17 dpc, it was not possible to reliably assess whether a subpopulation of NCPCs are associating with vascular endothelium within the pelvic ganglia like those seen in the bladder wall.

In order to determine whether heterogeneity of expression among Sox10+ cells also occurred at older ages, we performed a similar labeling of PGP9.5+ neurons and PECAM+ vasculature in adult bladder tissue. Consistent with the distribution of PECAM+ cells observed at 17.5 dpc, we observed rich vascularization of the submucosa beneath the urothelium (Fig. 9, left panel). In addition we also observed Sox10-H2BVenus+ cells whose nuclei were intimately associated with PECAM+ vasculature, as had been seen at 17.5 dpc (Fig 9, right panels). These observations indicate that the heterogeneity of Sox10+ cells in the bladder wall observed in fetal stages is due to maintenance of Sox10 expression in a variety of cell types throughout the bladder wall.

Figure 9. Association of Sox10+ NC-derived cells with vasculature in the adult bladder.

(A) Confocal image of a cryosection from adult mouse Sox10-H2BVenus transgenic bladder stained with PECAM (blue, endothelial cells of vasculature) and PGP9.5 (red, neuronal cells and urothelium) shown at 100× magnification. Individual Sox10 expressing cells are labeled by nuclear expression of the H2BVenus reporter (green). (B) Higher zoom confocal images from the boxed region in panel A show individual fluorophore labeling in the bladder wall just beneath the urothelium (200× magnification). (C) High magnification images reveal the presence of Sox10-H2BVenus+ cells whose nuclei are tightly associated with PECAM+ vaculature and appear to wrap around vessels (400× magnification). Abbreviations: det, detrusor muscle; sub, submucosa; um, urothelium. Scale bars = 100 microns.

2.6. In the adult bladder Sox10 expression is retained in glial cells

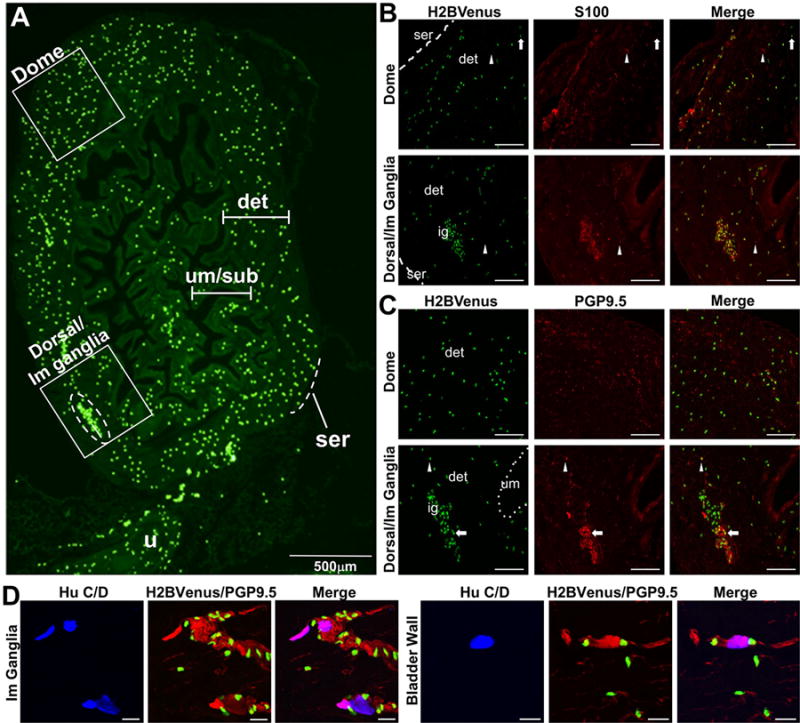

In the adult bladder, Sox10+ cells labeled by H2BVenus are relatively uniformly scattered throughout the detrusor and submucosa, with the exception of intramural ganglia located in the dorsal wall of the bladder, where numerous Sox10+ cells are clustered within the ganglia (Fig. 10A, dashed oval). Throughout the detrusor muscle, many of Sox10+ cells marked by H2BVenus express S100β+, which is a well established glial lineage marker and is consistent with the role of Sox10 in gliogenesis in multiple aspects of the peripheral nervous system. All of the H2BVenus+ cells within the adult bladder wall co-localize with S100β immunoreactivity, while 86 ± 1% of H2BVenus+ cells within intramural ganglia co-localize with S100β (n = 137 cells in 4 ganglia). Entire cell bodies that were clearly labeled by S100β immunoreactivity that were not also H2BVenus+ were also rarely observed (Fig. 10B, arrowheads). In the detrusor muscle of the bladder, we did not observe any colocalization of Sox10-H2BVenus in PGP9.5+ cells with large nuclei that would be characteristic of neurons in the bladder wall (Fig. 10C, “Dome”). However within intramural ganglia of the bladder wall, we did observe very infrequent Sox10+,PGP9.5+ double positive cells (Fig. 10C, “Dorsal/Im Ganglia”). Since PGP9.5 is known to label mature neurons and neuronal progenitor populations, it is possible that these double positive cells within the intramural ganglia may not yet be terminally differentiated and thus are marked by both perduring Sox10-H2BVenus and intiation of PGP9.5. However, PGP9.5 also labels non-neuronal cells types in the bladder including most prominently cells of the urothelium (Georgas et al., 2015; Harding et al., 2011). Therefore, to pinpoint the locations of mature neuronal bodies within the bladder wall, we stained for HuC/D, which distinctly labels the nucleus of differentiated neurons. Mature neurons marked by HuC/D within the bladder wall are very sparse (n = 12 total adult bladder sections surveyed; 26 total neurons observed), exhibit very large nuclei, and are detected in the bladder neck or lower anterior/ventral bladder wall within the detrusor. The distribution of HuC/D+ neurons in the bladder that we observed is consistent with prior reports in the rat (Forrest et al., 2014; Zvarova and Vizzard, 2005). No neurons labeled by HuC/D+ exhibited any co-localization with H2BVenus in adult mouse bladder (Fig. 10D). In contrast to the density of Sox10+ cells we observed in other bladder layers, the serosa and urothelium were devoid of Sox10-H2BVenus+ cells at all stages examined.

Figure 10. Heterogeneity of Sox10+ NC-derived cells in the adult mouse bladder.

(A) A low-magnification sagittal view of an adult bladder expressing the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene (4× magnification) shows three anatomic layers, urethra, and bladder dome labeled to provide orientation. The urothelium and submucosa present as convoluted folds in an empty adult bladder to provide room for expansion when filled with urine. An intramural ganglion is shown within the dashed oval. Two additional, smaller intramural ganglia are present along the dorsal aspect of the bladder. Areas of the bladder wall defined by boxed insets are shown on the right at higher magnification (200×) following immunohistochemistry performed with a glial marker (S100β) and a neuronal marker (PGP9.5). (B) In the bladder dome and dorsal wall of the bladder, the majority of Sox10+ cells are S100β+. However, infrequent Sox10+, S100β− cells (arrows) and very rare Sox10−, S100β+ cells (arrowheads) are also present. (C) In the detrusor muscle of the bladder dome, there is no colocalization of Sox10-H2BVenus with PGP9.5. However, within the intramural ganglia, there are infrequent Sox10-H2BVenus+ cells that also express PGP9.5 (arrow). A rare Sox10+, PGP9.5+ cell is present near the ganglion (arrowhead). (D) Sox10+ cells are in close proximity but do not colocalize with HuC/D+ large neuronal nuclei that are present in small groups of two to five cells within intramural ganglia (left) or present as individual cells in the bladder wall (right). Abbreviations: ser, serosa; det, detrusor muscle; um, urothelium; ig, intramural ganglion. Scale bars Panels B and C = 100 microns. Scale bars panel D = 20 microns

3. Discussion

In order to monitor routes of NCPCs to and within the LUT, we examined the distribution of Sox10+ cells labeled by expression of H2BVenus from the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene reporter (Corpening et al., 2011). This strategy is advantageous because it is a monoallelic system that permits direct fluorescence visualization, the nuclear localized reporter provides pinpoint localization of individual cells via association of the Histone2B fusion reporter with chromatin, and it does not suffer from effects of Sox10 haploinsufficiency. We initially established that the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene accurately reflects expression of Sox10 in migrating sacral NCPCs in the LUT by comparing it to a Sox10LacZ-KO/+ knock-in allele (Fig. 1) and our prior analysis of Sox10+ cells detected by in situ hybridization of fetal urogenital tracts (Wiese et al., 2012). Subsequently, we utilized the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene expression patterns to construct a spatiotemporal map of NCPC progression throughout the developing LUT and investigated the relationship of NCPCs to bladder innervation, smooth muscle differentiation, and vascularization during fetal development and in adult tissue. We observed that by 11.25 dpc, NCPCs have migrated ventrolaterally from the dorsal neural tube to surround the metanephric mesenchyme but do not appear to invade this structure (Fig. 3). This finding is in agreement with the work of others, who concluded that NCPCs are likely not essential to early kidney morphogenesis although they do integrate with the kidney later in development (Itaranta et al., 2009).

Previously it has not been clear when sacral NCPCs that populate the urogenital tract initiate neuronal differentiation. Prior studies that traced the migration of sacral NCPCs around the hindgut using a DβH-LacZ reporter suggested that neuronal differentiation may be occurring as these progenitors enter the urogenital sinus mesenchyme (Anderson et al., 2006). Consistent with this, we observed that neuronal glial lineage segregation is well underway within the pelvic ganglia at 14.5 dpc (Fig. 6). However, through sectional analysis at 11.25 dpc, we discovered that NCPCs were already undergoing neuronal differentiation, as evidenced by rare HuC/D+ cells admixed with Sox10+ cells (Fig. 3A″). The extent of differentiation clearly increased by 12 dpc (Fig. 3B″), when the embryo had elongated and the metanephric mesenchyme had ascended rostrally. These findings provide the first evidence that neuronal differentiation is an ongoing process concurrent with sacral NCPC migration, rather than a stepwise series of events that occur after sacral NCPCs coalesce to form pelvic ganglia.

Although NCPCs are actively differentiating as they populate the caudal regions of the embryo, we observed that these progenitors do not take up residence alongside the cloaca and coalesce to form pelvic ganglia until 12.5 dpc (Figures 2D, 4, and 5). There are large numbers of sacral NCPCs that migrate around the flanks of the extending hindgut on their way to populate the developing lower urinary tract. Our data is consistent with prior analyses of sacral NCPC that have documented migration around the hindgut at 11.5 dpc (Anderson et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2011). Discerning when the pelvic ganglia form becomes challenging given the close apposition of these migrating streams to the hindgut, the extension of the urorectal septum to separate the hindgut from the cloaca that will become the bladder, and the concurrent protrusion of the genital tubercle. The complex anatomy of the developing urogenital system as well as the presence of many NCPCs within the genital tubercle during early protrusion phases (Figure 5), and emergence of neuronal marker expression as NCPCs are progressing towards the cloaca (Figure 3) could lead to the confusion as to which NCPC subsets form the pelvic ganglia. By careful whole mount and sectional imaging, we show that streams of NCPC arrive at the edges of the cloaca, the site of future pelvic ganglia, and coalesce there at 12.5 dpc. The timing of this process and its spatiotemporal dynamics are of interest for future efforts that seek to define the signaling pathways that direct migration of NCPC to this very specific location.

Just as sacral NCPCs appear to follow a prescribed route from the neural tube to the pelvic ganglia, their emigration from the pelvic ganglia into the bladder appears tightly regulated and follows a very stereotypical pattern (Fig. 4). While the pelvic ganglia are clearly formed and recognizable by 12.5 dpc, exodus of NCPCs from the pelvic ganglia out into the bladder body is delayed until after 13.5 dpc. Migration into the bladder then proceeds in a stepwise fashion, with the first wave of NCPCs trekking along the lateral walls of the bladder toward the dome by 14.5 dpc, followed by a second wave migrating through the medial aspect of the bladder at 15.5 dpc. Perhaps the pelvic ganglion is the site of regulatory “instruction” for NCPCs prior to their immigration into the bladder, or perhaps the bladder mesenchyme requires additional time to generate effective levels of signaling molecules to promote entry of NCPCs into the bladder wall. This is definitely an avenue for future investigation, as deficits in guidance cues within the pelvic ganglia, or anywhere along the NCPC migratory pathway, may contribute to congenital abnormalities of bladder innervation (Woolf et al., 2014). Moreover, identification of signaling pathways that control trafficking of NCPCs into the bladder wall may be important for efforts seeking to innervate artificial scaffolds in bladder augmentation therapies (Atala, 2011).

Migration of NCPCs into the genital tubercle is also highly orchestrated and temporally regulated (Fig. 5). NCPC colonization of the genital tubercle precedes that of the bladder. There are distinct columnar aggregates of Sox10+ cells in the posterior of the genital tubercle on either side of the urethral plate epithelium at 11.5 dpc that are no longer present by 13.5dpc. One day later at 12.5dpc NCPCs have infiltrated the entire length of dorsal genital tubercle, but have not yet begun their migration into the bladder body. Interestingly, there are notable similarities in the patterns of gene expression for a Wnt5-associated network in the genital tubercle and the spatial distribution of Sox10+ neural crest that we observed (Chiu et al., 2010). Chiu et al observed the same distribution of Dkk1 at the dorsal aspect of the distal genital tubercle wrapping around in the spatial pattern we report here for Sox10+ NCPCs. Moreover, the patterns of Sox10+ NCPCs in the genital tubercle complement those reported for Wnt5a and Frzb, wherein NCPCs are absent from areas expressing these molecules (Chiu et al., 2010). Future studies will be needed to determine whether Wnt signaling functions to promote colonization or patterning of nerves in the developing genital tubercle. Discerning such regulatory events in normal development could provide insight for regenerative efforts following surgical or traumatic injury to penile nerves.

We also investigated other concomitant developmental processes, including bladder smooth muscle differentiation in relation to NCPC migration (Fig. 7). We found that smooth muscle differentiation is multifocal within the bladder, initiating at the bladder dome, immediately adjacent to the urachus, and shortly thereafter in the dorsal aspect of the primitive bladder near the most anterior aspect of the cloaca. Initial smooth muscle differentiation proceeds in a direction opposite innervation and does not appear to be dependent upon innervation. While it is possible that there could be some interdependency of these processes in the LUT, the spatial patterning and temporal progression that we observed appears distinct at each of the stages of LUT development we examined. The temporal appearance of smooth muscle cells marked by calponin in the developing LUT has not previously been reported and raises several possibilities for how this process is regulated. We observed the earliest and greatest intensity of calponin staining in the urachus. Signals emanating from the urachus is one possibility for regulation of smooth muscle differentiation. However at the temporal and spatial resolution of the studies we conducted, we cannot discern whether smooth muscle cells actually delaminate from the urachus around 12.5-13 dpc and infiltrate the bladder mesenchyme. Another possibility is that there are molecular signals forming a gradient that induces differentiation from the serosal surface inward. Clearly, additional investigation is required, particularly in light of a previous study implicating signaling gradients of Smad family members initiating at the urothelium and extending through bladder mesenchyme as essential for smooth muscle differentiation (Islam et al., 2013).

We paid particular attention to the formation of vasculature relative to colonization of the LUT by Sox10+ sacral NCPCs. We observed that vascularization of the developing bladder clearly occurs early (before 12.5 dpc) and precedes both innervation and smooth muscle differentiation (Fig. 7). Moreover, there is a spatial patterning to this process, with the mesenchyme of the bladder wall becoming vascularized first, followed later by extensive vascularization of the submucosa (Fig. 8). This is analogous to processes in the fetal intestine where NCPC migration throughout the gut is always preceded by formation of an established capillary plexus (Delalande et al., 2014; Hatch and Mukouyama, 2015). Despite the fact that there is close apposition of NCPCs to developing capillaries at later stages (17 dpc), our analysis of NCPC migration relative to LUT vascularization suggests that these processes are independent temporally and spatially. Mutant analyses in the fetal intestine have shown unequivocally that NCPC migration proceeds normally in the absence of an established vascular network (Delalande et al., 2014). Similar studies will be required in the future to rule out the possibility that there is any co-dependency between developing vasculature and innervation in the LUT.

In the course of our studies, we observed rare Sox10+ cells in the bladder wall that did not co-label with markers of glia (S100 β) or neurons (PGP9.5) (Figs. 8 and 9). Some of these were found in close association with PECAM+ endothelial cells of the vasculature. It is possible that these cells are glia that are not in immediate contact with neural processes, given prior reports of heterogeneous glial cells in the enteric nervous system that varied in expression of traditional glial markers, morphology and location in the intestinal wall (Boesmans et al., 2015). However, others have reported that vascular pericytes in the thymus, retina, and choroid derive from neural crest based on studies using Cre lineage tracing (Trost et al., 2013; Zachariah and Cyster, 2010). The nature and function of the rare Sox10+ vascular-associated cells we observe in the bladder wall remain to be investigated. Despite attempts to label these rare cells with pericyte lineage markers such as NG2 and PDGFRβ, we have not yet been successful in optimizing conditions that permit specific cell labeling (data not shown). Thus it is possible that NCPCs may give rise to pericytes in the LUT. Future work using robust Cre drivers for lineage tracing of neural crest will be necessary to definitively address this possibility.

Within intramural ganglia of mouse bladders, we detected colocalization of Sox10 with PGP9.5 in a minority of cells, both at late fetal (17 dpc) and adult (6 week) ages. This finding suggests that neuronal progenitors within the intramural ganglia have not yet undergone terminal lineage restriction (Fig. 10). It is known that the number of neurons in the pelvic ganglia more than doubles between birth and adulthood in the mouse, and evidence suggests this is the result of maturation of neuronal precursor cells into differing neuronal types rather than simple cell division (Yan and Keast, 2008). This process could account for the Sox10+/PGP9.5+ cells we observe within the intramural ganglia and in their immediate vicinity in the bladder wall. Less likely is the possibility that NCPCs remain at some undetermined location where they are actively giving rise to differentiating neurons. Future analyses using neural crest lineage tracers such as Wnt1-Cre and Nestin-Cre in combination with physiological labels of dividing cells will be needed to determine whether replacement of LUT neurons is a process that continues in older animals.

The studies we present here provide the first spatiotemporal map of sacral NCPC migration extending from the dorsal neural tube throughout the LUT of the mouse, encompassing early fetal development to adulthood. Our study reveals several potential key regulatory pause points along the pathway of sacral NCPC migration that will require further investigation. We have also described the patterns of smooth muscle differentiation and vascularization in the developing bladder and their temporal and spatial relationship to NCPC migration. This wild type sacral NCPC “roadmap” will facilitate future studies in mouse models of LUT dysfunction, as departures from this map should provide insight into pathological mechanisms of disease. Exciting future questions that can be pursued with the baseline established here include: What regulatory cues direct NCPCs towards the site of the pelvic ganglia? What controls lineage restriction as NCPC differentiate within the pelvic ganglia? And, Are vascular development and smooth muscle differentiation of the bladder altered if NCPCs are perturbed.

4. Methods

4.1 Animal Husbandry and Genotyping

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt University Medical Center approved all animal procedures. A LacZ knock-in allele of Sox10, Sox10tm1Weg/+, hereafter referred to as Sox10LacZ-KO/+ (RRID:MGI_#5552012) was a kind gift of Dr. Michael Wegner and bred to congenicity on a C3HeB/FeJ strain background (Jackson Laboratory, Stock #000658) (Britsch et al., 2001). Mice carrying the H2BVenus transgene reporter driven by Sox10 regulatory regions, Tg(Sox10−HIST2H2BE/Venus)ASout (RRID:MGI_#3769269), hereafter referred to as Sox10-H2BVenus, were maintained by backcrossing to C3Fe females. Sox10LacZ-KO/+ mice were genotyped using primers and PCR parameters listed in Table 1. Sox10-H2BVenus transgenic mice were genotyped with T7, SP6, and internal primers to ensure integrity of the entire transgene as previously described (Corpening et al., 2011; Deal et al., 2006) (See Table 1). Timed matings were set to obtain staged mouse fetuses, designating the morning of plug formation as 0.5 days post coitum (dpc). The staging of fetuses was confirmed by examination of fore and hind limbs in comparison to published standards (Kaufman, 1995). Slight variations in age (+/− 0.5 days) were noted between fetuses within a litter and ages confirmed by limb staging are indicated on figure panels. Litters were typically dissected in the morning, however some dissections were done late in the day to obtain fetuses of the desired stage.

Table 1.

Primers Used to Genotype Sox10LacZ/KO and Sox10H2BVenus Mice

| Genotype | 5′ to 3′ Sequence | PCR Parameters | Expected Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sox10LacZ/KO |

1: CAGGTGGGCGTTGGGCTCTT 2: CAGAGCTTGCCTAGTGTCTT 3: TAAAAATGCGCTCAGGTCAA |

94°C, 5 min; 35 cycles of: (94°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30s, ramp 0.5C/s to 72°C; 72°C, 30 s, ramp 0.5°C/s to 94°C); 72°C, 10 min | Wild type allele ~500bp |

| LacZ allele ~600bp | |||

| Sox10H2BVenus |

Sp6 Forward: GTTTTTTGCGATCTGCCGTTTC Sp6 Reverse: GGCACTTTCATGTTATCTGAGG |

as above | 227bp |

|

T7 Forward: TCGAGCTTGACATTGTAGGAC T7 Reverse: AAGAGCAAGCCTTGGAACTG |

as above | 202bp | |

|

Internal Forward: CTGGTCGAGCTCGACGGCGACGTA Internal Reverse: AGTCGCGGCCGCTTTACTTG |

94°C, 5 min; 35 cycles of: (94°C, 45 s; 55°C, 45s, ramp 0.5C/s to 72°C; 72°C, 45 s, ramp 0.5°C/s to 94°C); 72°C, 10 min | 580bp |

4.2 Embryo Procurement and Tissue Preparation

At the desired time points, embryos were harvested into 1× ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (1× PBS, Sigma) and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF, Sigma) from 6 h to overnight at 4°C, depending on size. Embryos were equilibrated in 1× PBS containing 30% sucrose and stored at 4°C. As needed, further micro-dissection of lower urinary tract organs was performed, and embryos and tissues to be sectioned were cryopreserved in tissue freezing media (General Data Healthcare). Tissues were sectioned (20 μm thick ness) using a Leica CM1900 cryostat (Leica) and processed through immunohistochemistry.

4.3 Whole Mount Detection of βGal and Immunohistochemistry

For detection of β gal expression, organs of the lower urinary tract were micro-dissected and subsequently fixed in neutral buffered formalin (NBF) at 4°C for 20 min, then washed, stained at room temperature for up to 72 h, and stored according to established protocol (Chandler et al., 2007; Deal et al., 2006).

For immunohistochemical localization of cell type specific markers, cryosections were mounted on microscope slides previously coated with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (3-APES, Sigma) to promote adhesion according to established methods (Maddox and Jenkins, 1987) and subsequently warmed to 37°C for 30 min. Tissue freezing media was removed and tissue permeabilization enhanced by washing the slides once in 1× PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 8 min. After blocking for 1 hr at RT in 1× PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 017-000-121, RRID:AB_2337258) and 0.1% BSA, Fraction V (Sigma), primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution were applied at 4°C at concentrations specified in Table 2. Following washes in 1× PBS, appropriate secondary antibodies diluted in blocking solution were added for 1 hr at RT. After final washes in 1× PBS with 0.3% TX-100, slides were incubated in quenching solution (0.5mM cupric sulfate in 50mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.0) for 10 min to minimize autofluorescence (Polanco et al., 2010), and the quenching reaction was terminated by transferring the slides to sterile water. Slides were then immediately mounted with Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences, Inc.). When it was desirable to visualize nuclei, staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen, 1:50,000) was performed for 5 min in 1× PBS, followed by three 10-min washes, prior to mounting coverslips.

Table 2.

Antibodies Used in Immunohistochemical Analysis

| Antigen | Host | Supplier | Catalog No.; RRID | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFABP | Rabbit | Gift of T. Muller | N/A | 1:1,000 |

| PGP9.5 | Rabbit | Biogen (antibody no longer sold) | 7863504; N/A | 1:4,000 |

| Class III β-tubulin (TuJ1) | Rabbit | Covance | PRB-435P; AB_291637 | 1:10,000 |

| HuC/D | Human | Gift of V. Lennon | N/A | 1:10,000 |

| S100β | Rabbit | Dako | Z0311; AB_10013383 | 1:500 |

| Calponin | Rabbit | Abcam | ab46794; AB_2291941 | 1:250 – 1:500 |

| PECAM1 (CD31) | Rat | Abcam | ab28364; AB_726362 | 1:500 |

Abbreviations: N/A, not applicable; RRID, Research Resource Identifier

4.4 Fluorescent Microscopy

Initial imaging of embryos and micro-dissected urogenital tracts was performed on a Leica M205 FA microscope with an ORCA-Flash4.0 V2 digital CMOS camera (Hamamatsu) or a Zeiss M2Bio microscope with a Retiga 4000R-F-M-C camera (Q-Imaging) and accompanying software. Imaging of cryosections was initially performed on a Leica DMI6000 B microscope using SimplePCI version 6.6.0.16 imaging software (Hamamatsu). Confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss Scanning Microscope LSM510 using a 633 nm laser for imaging Cy5 (649–745 bandpass filter), 543 nm laser for imaging Cy3 (560–615 bandpass filter), and a 488 nm laser for imaging Venus (YFP, 505–550 bandpass filter) to visualize transgene expression and secondary antibody fluorophores. Images were captured with the Zeiss LSM Image Browser Software (free download, http://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/en_de/website/downloads/lsm-image-browser.html). Images were then exported from the Image Browser software as .tiff files and assembled in Adobe Photoshop (2014 2.2 release, Adobe Systems Inc.).

4.5 Cell Counting

Alternating sections of 18 micron thickness were collected and processed through immunohistochemistry to avoid counting the same cells twice then imaged as above. Confocal images were exported as .tiff files for assembly and analysis in Adobe Photoshop. Due to variation of expression intensity of the Sox10-H2BVenus transgene in different cell types, images were minimally adjusted for optimal brightness and contrast. Co-localization of transgene expression in neurons (PGP9.5+) and glia (BFABP+ or S100b+) was manually quantified by visual inspection of assembled confocal stacks. Venus+ cells were counted within minimally four independent sections of fetal pelvic ganglia, adult bladder neck, or adult bladder wall. Average values are reported accompanied by standard error of the mean.

Table 3.

Secondary Antibodies Used in Immunohistochemical Analysis

| Secondary Antibody Detection and Type | Supplier | RRID | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cy3 Donkey anti-rabbit | Jackson ImmunoResearch | AB_2307443 | 1:1,000 |

| Cy5 Donkey anti-human | Jackson ImmunoResearch | AB_2340539 | 1:200 |

| Cy5 Donkey anti-rat | Jackson ImmunoResearch | AB_2340671 | 1:500 |

Abbreviation: RRID, Research Resource Identifier

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Michael Wegner for providing Sox10LacZ-KO/+ mice, Dr. Vanda Lennon for providing Hu antibody, and Dr. T. Muller for providing BFABP antibody. We appreciate the assistance of Dr. Sam Wells and the support staff of the Cell Imaging Shared Resource Core at Vanderbilt University for advice on confocal imaging. The Cell Imaging Shared Resource Core is supported by NIH grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, HD15052, DK59637, and EY08126. Kylie Muccilli of the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Research on Human Development provided graphic design support. We are grateful to K. Elaine Ritter for thorough reading and thoughtful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by funding from a US National Institutes of Health grant from NIDDK (R01DK078158, R56DK078158, RC1DK086594) to E.M.S2.

Footnotes

Author contributions

AC collected embryos and performed imaging. SJI collected embryos, performed immunohistochemistry, and captured images. CBW collected embryos, performed immunohistochemistry, captured images, performed cell counts, prepared draft figures, and aided in preparation of the text. KKD collected embryos, performed immunohistochemistry, captured images, participated with data analysis, prepared figures and assisted with compilation of the manuscript. EMS2 conceived the study and directed the project, participated with data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Anderson RB, Stewart AL, Young HM. Phenotypes of neural-crest-derived cells in vagal and sacral pathways. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;323:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atala A. Tissue engineering of human bladder. Br Med Bull. 2011;97:81–104. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atala A, Bauer SB, Soker S, Yoo JJ, Retik AB. Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet. 2006;367:1241–1246. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur P, Bronner-Fraser M, Sauka-Spengler T. Genomic code for Sox10 activation reveals a key regulatory enhancer for cranial neural crest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3570–3575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906596107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancur P, Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner M. A Sox10 enhancer element common to the otic placode and neural crest is activated by tissue-specific paralogs. Development. 2011;138:3689–3698. doi: 10.1242/dev.057836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesmans W, Lasrado R, Vanden Berghe P, Pachnis V. Heterogeneity and phenotypic plasticity of glial cells in the mammalian enteric nervous system. Glia. 2015;63:229–241. doi: 10.1002/glia.22746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britsch S, Goerich DE, Riethmacher D, Peirano RI, Rossner M, Nave KA, Birchmeier C, Wegner M. The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev. 2001;15:66–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.186601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler KJ, Chandler RL, Broeckelmann EM, Hou Y, Southard-Smith EM, Mortlock DP. Relevance of BAC transgene copy number in mice: transgene copy number variation across multiple transgenic lines and correlations with transgene integrity and expression. Mamm Genome. 2007;18:693–708. doi: 10.1007/s00335-007-9056-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu HS, Szucsik JC, Georgas KM, Jones JL, Rumballe BA, Tang D, Grimmond SM, Lewis AG, Aronow BJ, Lessard JL, Little MH. Comparative gene expression analysis of genital tubercle development reveals a putative appendicular Wnt7 network for the epidermal differentiation. Dev Biol. 2010;344:1071–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpening JC, Deal KK, Cantrell VA, Skelton SB, Buehler DP, Southard-Smith EM. Isolation and live imaging of enteric progenitors based on Sox10−Histone2BVenus transgene expression. Genesis. 2011;49:599–618. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal KK, Cantrell VA, Chandler RL, Saunders TL, Mortlock DP, Southard-Smith EM. Distant regulatory elements in a Sox10−beta GEO BAC transgene are required for expression of Sox10 in the enteric nervous system and other neural crest-derived tissues. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1413–1432. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delalande JM, Natarajan D, Vernay B, Finlay M, Ruhrberg C, Thapar N, Burns AJ. Vascularisation is not necessary for gut colonisation by enteric neural crest cells. Dev Biol. 2014;385:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duband JL, Gimona M, Scatena M, Sartore S, Small JV. Calponin and SM 22 as differentiation markers of smooth muscle: spatiotemporal distribution during avian embryonic development. Differentiation. 1993;55:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1993.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest SL, Osborne PB, Keast JR. Characterization of axons expressing the artemin receptor in the female rat urinary bladder: a comparison with other major neuronal populations. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:3900–3927. doi: 10.1002/cne.23648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freem LJ, Escot S, Tannahill D, Druckenbrod NR, Thapar N, Burns AJ. The intrinsic innervation of the lung is derived from neural crest cells as shown by optical projection tomography in Wnt1-Cre;YFP reporter mice. J Anat. 2010;217:651–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Rivera A, Tao L, Zhang X. Genetically modified T cells targeting neovasculature efficiently destroy tumor blood vessels, shrink established solid tumors and increase nanoparticle delivery. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:2483–2492. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgas KM, Armstrong J, Keast JR, Larkins CE, McHugh KM, Southard-Smith EM, Cohn MJ, Batourina E, Dan H, Schneider K, Buehler DP, Wiese CB, Brennan J, Davies JA, Harding SD, Baldock RA, Little MH, Vezina CM, Mendelsohn C. An illustrated anatomical ontology of the developing mouse lower urogenital tract. Development. 2015;142:1893–1908. doi: 10.1242/dev.117903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding SD, Armit C, Armstrong J, Brennan J, Cheng Y, Haggarty B, Houghton D, Lloyd-MacGilp S, Pi X, Roochun Y, Sharghi M, Tindal C, McMahon AP, Gottesman B, Little MH, Georgas K, Aronow BJ, Potter SS, Brunskill EW, Southard-Smith EM, Mendelsohn C, Baldock RA, Davies JA, Davidson D. The GUDMAP database–an online resource for genitourinary research. Development. 2011;138:2845–2853. doi: 10.1242/dev.063594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch J, Mukouyama YS. Spatiotemporal mapping of vascularization and innervation in the fetal murine intestine. Dev Dyn. 2015;244:56–68. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam SS, Mokhtari RB, Kumar S, Maalouf J, Arab S, Yeger H, Farhat WA. Spatio-temporal distribution of Smads and role of Smads/TGF-beta/BMP-4 in the regulation of mouse bladder organogenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itaranta P, Viiri K, Kaartinen V, Vainio S. Lumbo-sacral neural crest derivatives fate mapped with the aid of Wnt-1 promoter integrate but are not essential to kidney development. Differentiation. 2009;77:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur RP. Colonization of the murine hindgut by sacral crest-derived neural precursors: experimental support for an evolutionarily conserved model. Dev Biol. 2000;227:146–155. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MH. The Atlas of Mouse Development. First. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- King PH, Redden D, Palmgren JS, Nabors LB, Lennon VA. Hu antigen specificities of ANNA-I autoantibodies in paraneoplastic neurological disease. J Autoimmun. 1999;13:435–443. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1999.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajiness JD, Snider P, Wang J, Feng GS, Krenz M, Conway SJ. SHP-2 deletion in postmigratory neural crest cells results in impaired cardiac sympathetic innervation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E1374–1382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319208111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JI, Heuckeroth RO. Enteric nervous system development: migration, differentiation, and disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G1–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00452.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam Van Ba O, Aharony S, Loutochin O, Corcos J. Bladder tissue engineering: a literature review. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;82–83:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Calloni GW, Dupin E. The stem cells of the neural crest. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1013–1019. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.8.5641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox PH, Jenkins D. 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APES): a new advance in section adhesion. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:1256–1257. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.10.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundell NA, Plank JL, LeGrone AW, Frist AY, Zhu L, Shin MK, Southard-Smith EM, Labosky PA. Enteric nervous system specific deletion of Foxd3 disrupts glial cell differentiation and activates compensatory enteric progenitors. Dev Biol. 2012;363:373–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser MA, Southard-Smith EM. Balancing on the crest - Evidence for disruption of the enteric ganglia via inappropriate lineage segregation and consequences for gastrointestinal function. Dev Biol. 2013;382:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermayr F, Hotta R, Enomoto H, Young HM. Development and developmental disorders of the enteric nervous system. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:43–57. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberpenning F, Meng J, Yoo JJ, Atala A. De novo reconstitution of a functional mammalian urinary bladder by tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:149–155. doi: 10.1038/6146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanco JC, Wilhelm D, Davidson TL, Knight D, Koopman P. Sox10 gain-of-function causes XX sex reversal in mice: implications for human 22q-linked disorders of sex development. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:506–516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakova O, Sommer L. Neural crest-derived stem cells. Harvard Stem Cell Institute; Cambridge (MA): 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost A, Schroedl F, Lange S, Rivera FJ, Tempfer H, Korntner S, Stolt CC, Wegner M, Bogner B, Kaser-Eichberger A, Krefft K, Runge C, Aigner L, Reitsamer HA. Neural crest origin of retinal and choroidal pericytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7910–7921. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verberne ME, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, van Iperen L, Poelmann RE. Distribution of different regions of cardiac neural crest in the extrinsic and the intrinsic cardiac nervous system. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:191–204. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200002)217:2<191::AID-DVDY6>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chan AK, Sham MH, Burns AJ, Chan WY. Analysis of the sacral neural crest cell contribution to the hindgut enteric nervous system in the mouse embryo. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:992–1002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.002. e1001-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese CB, Fleming N, Buehler DP, Southard-Smith EM. A Uchl1-Histone2BmCherry:GFP-gpi BAC transgene for imaging neuronal progenitors. Genesis. 2013;51:852–861. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese CB, Ireland S, Fleming NL, Yu J, Valerius MT, Georgas K, Chiu HS, Brennan J, Armstrong J, Little MH, McMahon AP, Southard-Smith EM. A genome-wide screen to identify transcription factors expressed in pelvic Ganglia of the lower urinary tract. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:130. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf AS, Stuart HM, Roberts NA, McKenzie EA, Hilton EN, Newman WG. Urofacial syndrome: a genetic and congenital disease of aberrant urinary bladder innervation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29:513–518. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Keast JR. Neurturin regulates postnatal differentiation of parasympathetic pelvic ganglion neurons, initial axonal projections, and maintenance of terminal fields in male urogenital organs. J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1169–1183. doi: 10.1002/cne.21593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young HM, Bergner AJ, Muller T. Acquisition of neuronal and glial markers by neural crest-derived cells in the mouse intestine. J Comp Neurol. 2003;456:1–11. doi: 10.1002/cne.10448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah MA, Cyster JG. Neural crest-derived pericytes promote egress of mature thymocytes at the corticomedullary junction. Science. 2010;328:1129–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.1188222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvarova K, Vizzard MA. Distribution and fate of cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide (CARTp)-expressing cells in rat urinary bladder: a developmental study. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489:501–517. doi: 10.1002/cne.20657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]