Abstract

Immune cell recognition of bacterial products usually occurs via specific pattern recognition receptors, but new research recently published in Cell by Wolf et al. (2016) demonstrates that the glycolytic enzyme hexokinase can act as an innate immune sensor by binding to bacterial derived N-acetylglucosamine (NAG).

The ability to detect and respond to pathogens is essential for an organism’s survival, and one of the first lines of defense against infection is the innate immune system. Metabolic adaptations are at the nexus of innate immune responses. Reprogramming of cellular metabolism in innate immune cells is necessary for their efficient activation, and many antimicrobial defenses such as nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and itaconate are products of metabolic processes (O’Neill and Pearce, 2016). Adding to the diverse role that metabolism has in innate immunity, new research by Wolf et al. (2016) demonstrates that the glycolytic enzyme hexokinase senses Gram-positive bacteria and facilitates inflammasome activation.

Activation of innate immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DC) occurs through detection of pathogen specific molecular signatures by pattern recognition receptors (PRR). Activation of PRRs, such as the canonical TLR and NOD-like receptors, leads to the release of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, and the induction of a full-scale innate immune defense. This process can be mediated through NOD-like receptor (NLR) family, pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3). Upon activation, NLRP3 forms an inflammasome complex in association with caspase-1 and the adaptor protein ASC, mediating mature IL-1β and IL-18 production.

Mitochondria are key in the induction of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and the work of Wolf et al. (2016) provides an intriguing link between mitochondria and NLRP3 activation. They demonstrate in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-primed bone marrow-derived macrophages that hexokinase responds to elevated concentrations of N-acetylglucosamine (NAG), a sugar subunit found in bacterial peptidoglycan (PGN), by dissociating from mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs). Although NAG can both inhibit hexokinase activity, as well as cause its dissociation from VDAC, the induction of the NLRP3 inflammasome appears to be mediated by the latter. Using a peptide that competes with hexokinase for the binding site of VDAC, they find that dissociation of hexokinase from VDAC induces IL-1β and IL-18 production in an NLRP3-dependent manner. Using excess glucose-6-phosphate (hexokinase’s enzymatic product) or the glucose analog 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), Wolf et al. (2016) also demonstrate that induction of IL-1β occurs following inhibition of hexokinase. To assess these effects in vivo, Wolf et al. (2016) utilized PGN from bacillus anthracis, which contains deacetylated NAG and does not activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. When they re-acetylated the b. anthracis PGN, thus enhancing NAG concentration, an IL-1β dependent inflammatory response was induced.

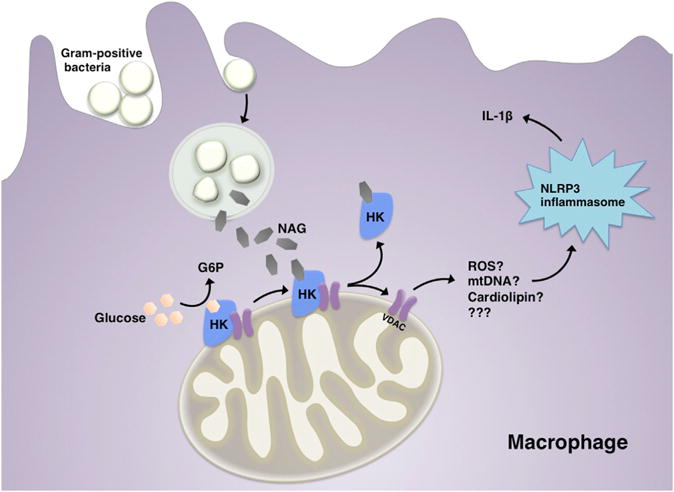

Collectively, their results suggest that NAG induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation through binding and dissociating hexokinase (Figure 1). The signal connecting hexokinase dissociation from VDAC and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome remains to be determined. Potassium efflux is a common mechanism underlying NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Muñoz-Planillo et al., 2013), but surprisingly it does not appear to play a role in PGN-induced inflammasome activation, as increasing extracellular potassium had no effect on IL-1β production. Also NLRP3 inflammasome activation was not due to loss of mitochondrial integrity, as mitochondrial membrane potential was maintained following PGN administration. Interestingly, this effect is distinct from a previous study that found 2-DG reduced mitochondrial membrane potential in macrophages (Nomura et al., 2015). Another mechanism could be mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) release, as increased mtDNA was evident in the cytosol in response to PGN. Other inflammasome activators, including mitochondrial ROS and cardiolipin, may also contribute to these effects (Sutterwala et al., 2014).

Figure 1. N-acetylglucosamine Causes NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Binding to Hexokinase.

Hexokinase is a glycolytic enzyme that converts glucose to glucose-6-phosphate (G6P). New research from Wolf et al. (2016) demonstrates that bacterial N-acetylglucosamine (NAG), derived from phagocytosed Gram-positive bacteria, can bind to and inhibit hexokinase (HK) in macrophages. NAG binding can also cause the dissociation of HK from voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs) on the outer mitochondrial membrane. This in turn leads to NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β release by an undetermined mechanism, which could be related to release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), cardiolipin, or some other factor (???).

VDAC interacts with hexokinase and is implicated in NLRP3 activation in response to noxious stimuli including monosodium urate, silica, and alum (Zhou et al., 2011). Hexokinase dissociation may allow VDAC to carry out this role. It willbe informative to block or silence VDAC to explore its function in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in response to PGN, and if hexokinase dissociation regulates mitochondrial ROS or mtDNA release (Zhou et al., 2011).

In macrophages, NLRP3 relocates to mitochondria following stimulation with alum or nigericin, possibly to be in closer proximity to activating signals from mitochondria (Zhou et al., 2011). Mitochondria may facilitate assembly of the inflammasome, and mitochondrial structure is key for its activation. Inducing mitochondrial fission might restrict NLRP3 inflammasome assembly/activation and NLRP3 has been shown to associate with the mitochondrial fusion protein mitofusin 2 (Ichinohe et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015). It would be intriguing to investigate whether such alterations in mitochondrial dynamics affect hexokinase dissociation.

NAG is an atypical microbial danger signal as it is derived from PGN but is also synthesized in the glycosylation pathway as uridine diphosphate (UDP-NAG), which can then be released following degradation of glycosylated proteins. Since intrinsically produced NAG is likely to be present at low concentrations, higher concentrations are likely required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Wolf et al. (2016) showed that NAG in the low millimolar range inhibited purified hexokinase. However, enhanced IL-1β secretion was only observed in cells treated with much higher concentrations, likely suggesting that NAG was not readily entering the cell or that hexokinase dissociation from the mitochondria occurs at a higher concentration than hexokinase inhibition. Determining whether the concentration of PGN-derived NAG in the cytoplasm after bacterial infection is sufficient to dissociate hexokinase from VDAC could be a focus of future work.

Wolf et al. (2016) found that disruption of hexokinase activity by high concentrations of 2-DG also enhanced IL-1β secretion. Although previously observed (Nomura et al., 2015), this result contrasts with studies demonstrating that blocking glycolysis with 2-DG can inhibit IL-1β activation (O’Neill and Pearce, 2016; Tannahill et al., 2013). It is conceivable that differences in stimulation conditions, 2-DG concentration, level of cell death, or the timing of hexokinase inhibition could explain these differential effects. Metabolic reprograming of macrophages and DCs occurs after PRR stimulation, and aerobic glycolysis is essential in the development of subsequent inflammatory responses (Everts et al., 2014; O’Neill and Pearce, 2016). In the current study, macrophages exposed to NAG or PGN were previously stimulated with LPS, which induces a classical inflammatory phenotype. Given the importance of aerobic glycolysis in classical macrophage activation, it would be informative to observe what effect NAG has on bioenergetics. It is possible that in a system using live Gram-positive bacteria, initial inflammatory signals would come from other bacterial components, such as muramyl dipeptide, and that NAG induced NLRP3 activation would occur at a later time point, when sufficient NAG has been digested and released into the cytosol. Comparing mitochondrial respiration and aerobic glycolysis in macrophages after exposure to PGN and NAG versus exposure to whole bacteria would help address these questions.

The NLRP3 inflammasome is dysregulated in a variety of metabolic and inflammatory diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, NLRP3 is an appealing therapeutic target and understanding what regulates or activates it is of vital importance. The exciting results of Wolf et al. (2016) demonstrate that the glycolytic enzyme hexokinase acts as a sensor of Gram-positive bacteria, highlighting a surprising discovery in the link between innate immune responses and metabolism.

References

- Everts B, Amiel E, Huang SC-C, Smith AM, Chang C-H, Lam WY, Redmann V, Freitas TC, Blagih J, van der Windt GJW, et al. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:323–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe T, Yamazaki T, Koshiba T, Yanagi Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17963–17968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312571110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Núñez G. Immunity. 2013;38:1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura J, So A, Tamura M, Busso N. J Immunol. 2015;195:5718–5724. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill LA, Pearce EJ. J Exp Med. 2016;213:15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Won JH, Hwang I, Hong S, Lee HK, Yu JW. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15489. doi: 10.1038/srep15489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutterwala FS, Haasken S, Cassel SL. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1319:82–95. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, Frezza C, Bernard NJ, Kelly B, Foley NH, et al. Nature. 2013;496:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AJ, Reyes CN, Liang W, Becker C, Shimada K, Wheeler ML, Cho HC, Popescu NI, Coggeshall KM, Arditi M, et al. Cell. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.076. Published online June 29, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]