Abstract

Increased walking knee joint stiffness has been reported in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) as a compensatory strategy to improve knee joint stability. However, presence of episodic self-reported knee instability in a large subgroup of patients with knee OA may be a sign of inadequate walking knee joint stiffness. The objective of this work was to evaluate the differences in walking knee joint stiffness in patients with knee OA with and without self-reported instability and examine the relationship between walking knee joint stiffness with quadriceps strength, knee joint laxity, and varus knee malalignment. Overground biomechanical data at a self-selected gait velocity was collected for 35 individuals with knee OA without self-reported instability (stable group) and 17 individuals with knee OA and episodic self-reported instability (unstable group). Knee joint stiffness was calculated during the weight-acceptance phase of gait as the change in the external knee joint moment divided by the change in the knee flexion angle. The unstable group walked with lower knee joint stiffness (p=0.01), mainly due to smaller heel-contact knee flexion angles (p<0.01) and greater knee flexion excursions (p<0.01) compared to their knee stable counterparts. No significant relationships were observed between walking knee joint stiffness and quadriceps strength, knee joint laxity or varus knee malalignment. Reduced walking knee joint stiffness appears to be associated with episodic knee instability and independent of quadriceps muscle weakness, knee joint laxity or varus malalignment. Further investigations of the temporal relationship between self-reported knee joint instability and walking knee joint stiffness are warranted.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, Instability, Stiffness, Kinematics, Gait

INTRODUCTION

Self-reported knee instability, described as buckling, shifting, or giving way of the knee joint is a prevalent complaint in as high as 60–80% of patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) [1–3]. While passive knee joint laxity has been identified as a risk factor associated with knee OA [4–6], evidence suggests that joint laxity does not necessarily play a role in self-reported knee instability in this patient population [2, 7, 8]. Previous attempts at exploring the potential relationships between other OA-related risk factors such as quadriceps strength, varus knee malalignment, and radiographic disease severity with self-reported instability have also been inconclusive [7, 9, 10].

Although passive measures of knee joint function appear to be inadequate in predicting self-reported knee instability in patients with knee OA, dynamic evaluation of knee joint function may provide more relevant insight. For example, it was recently reported that patients with knee OA and self-reported instability exhibit excessive medial compartment joint contact point translations and velocities during the weight-acceptance phase of downhill gait when compared to patients with knee OA without complaints of instability [11]. Increased levels of medial compartment muscle co-contraction involving the medial quadriceps, medial hamstrings, and medial gastrocnemius have also been reported in knee OA patients with self-reported instability during the weight-acceptance phase of level ground gait [9]. This increase in muscle co-contraction is presumably an attempt at stabilizing the unstable medial compartment, albeit unsuccessfully as episodic instability often persists.

In order to compensate for the increased laxity of the knee joint, it has been suggested that patients with knee OA often adopt a knee-stiffening gait strategy [4, 12, 13]. In support of this premise, increased levels of walking knee joint stiffness, which is a measure of increased resistance to movement provided by the muscles and the soft tissues of the knee joint, have been reported in patients with knee OA [13, 14]. Given the lack of differences in passive knee joint laxity between knee OA patients with and without self-reported instability [2, 7, 8], it stands to reason that in the absence of adequate walking knee joint stiffness, knee joint laxity could play a more significant role in causing dynamic episodes of instability.

From a biomechanical perspective, walking knee joint stiffness is defined as the slope of the line when the external knee flexion moment is plotted against the knee flexion angle [15]. Either increased external knee flexion moment or decreased knee flexion excursion can lead to increased walking knee joint stiffness. It was previously reported that 39% of the variance in walking knee joint stiffness during the weight-acceptance phase of gait was due to reduced knee flexion excursion in patients with knee OA, while changes in peak external knee flexion moment only accounted for a further 7% of the variance [14]. As such, it was recently reported that patients with knee OA and self-reported knee instability walk with increased knee flexion excursions during the weight-acceptance phase of gait compared to their counterparts without instability [16]. However, whether increased knee flexion excursion can lead to alterations in walking knee joint stiffness in patients with knee OA and self-reported instability during gait remains unknown.

The main objective of the current study was to compare walking knee joint stiffness during the weight-acceptance phase of gait between patients with knee OA with and without self-reported instability. We hypothesized that patients with self-reported instability would have reduced walking knee joint stiffness due to greater knee flexion excursions compared to their counterparts without reports of instability. In addition, a secondary aim of the current study was to evaluate the associations between walking knee joint stiffness with quadriceps strength, passive medial compartment joint laxity, and varus knee malalignment. It was hypothesized that quadriceps strength, passive medial compartment joint laxity, and varus knee malalignment would not be associated with walking knee joint stiffness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Biomechanical data from a subsample of 52 participants recruited as part of a randomized clinical trial of exercise therapy for knee OA [17] were utilized in this study. Participants were included in the current study if they met the 1986 American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria for knee OA [18] and had primarily medial compartment disease of greater than II on the Kellgren and Lawrence radiographic disease severity scale [19]. Participants with radiographic disease severity of grade II or greater in the lateral tibiofemoral compartment were excluded. Additionally, all participants were excluded if they had a history of lower extremity total joint arthroplasty, cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or neurological disorders that could affect their gait. For all participants, the knee in which they reported symptoms or episodes of instability was designated as the test knee. In cases where both knees experienced symptoms or instability, the more problematic knee as chosen by the participant was designated as the test knee.

Participants with knee OA were stratified into either a knee unstable (n = 17) or a knee stable (n = 35) group based on their response on a 6-point numeric scale to the following questions adopted from the Knee Outcome Survey [20]: “To what degree does giving way, buckling, or shifting of the knee affect your level of daily activity?” The definitions of the 6 levels of instability are provided in Table 1. The knee unstable group included patients indicating that the symptom of instability affects their ability to perform activities of daily living (rating of ≤ 3), while the knee stable group consisted of patients who reported no episodes of instability or did not perceive the symptom to affect their daily activities (rating of >4) [1]. The test-retest reliability of this tool has previously been determined as adequate with intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.72 in a population including individuals with knee OA [1]. All data reported in this study (Tables 1–4) were collected at baseline and prior to receiving any intervention. All participants provided written informed consent approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s institutional review board.

TABLE 1.

Summary of participant characteristics.*

| Stable (n=35) | Unstable (n=17) | Significance (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.2 ± 7.5 | 61.3 ± 6.5 | 0.38 |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (37%) | 11 (65%) | 0.06 |

| Height (cm) | 172.8 ± 8.5 | 166.5 ± 5.4 | <0.01 |

| Weight (kg) | 85.4 ± 14.8 | 84.6 ± 12.0 | 0.84 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.7 ± 5.5 | 30.6 ± 4.8 | 0.24 |

| Self-reported Knee stability Scale, n (%) | |||

| 0 = The symptom prevents all daily activity | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 1 = The symptom affects daily activity severely | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | |

| 2 = The symptom affects daily activity moderately | 0 (0%) | 5 (29%) | <0.01 |

| 3 = The symptom affects daily activity slightly | 0 (0%) | 11 (65%) | |

| 4 = The symptom does not affect daily activity | 12 (34%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 5 = No giving way, buckling, or shifting of the knee | 23 (66%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Medial Compartment radiographic severity, n (%)† | |||

| Grade 2 | 5 (14%) | 3 (18%) | |

| Grade 3 | 21 (60%) | 9 (53%) | 0.89 |

| Grade 4 | 9 (26%) | 5 (29%) | |

| WOMAC | |||

| Pain Score (0–20) | 4.8 ± 3.3 | 6.8 ± 2.6 | 0.04 |

| Physical Function Score (0–68) | 14.8 ± 10.7 | 24.3 ± 7.0 | <0.01 |

| Stiffness Score (0–8) | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | <0.01 |

| Gait Speed (m/s) | 1.31 ± 0.16 | 1.20 ± 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Quadriceps Muscle Strength (Nm/Kg) | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 0.34 |

| Medial Compartment Joint Laxity (mm) | 7.8 ± 2.6 | 7.6 ± 2.9 | 0.75 |

| Varus Knee Alignment (degrees) | 174.1± 3.0 | 171.1 ± 4.9 | 0.02 |

Values are mean ± standard deviations unless indicated otherwise. WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

All patients had to have at least a grade 2 knee OA to be included in the study.

TABLE 4.

Strength of association between walking knee joint stiffness during the weight-acceptance phase of gait and quadriceps strength, medial compartment joint laxity and varus knee malalignment. All analyses were adjusted for the potential effects of gait speed and gender.

| β | SE | 95% CI | R2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quadriceps Muscle Strength | −0.16 | 0.002 | −0.50,0.17 | 0.10 | 0.33 |

| Medial Compartment Joint Laxity | 0.002 | 0.028 | −0.053,0.060 | 0.03 | 0.94 |

| Varus Knee Malalignment | 0.001 | 0.023 | −0.045,0.046 | 0.06 | 0.98 |

beta = standardized coefficient; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval

Gait Analysis

Participants wore their usual walking shoes and walked along an 8.5 m vinyl-tiled level walkway at a self-selected speed. An eight camera Vicon® 612 motion measurement system (Vicon Peak, VICON Motion Systems, Oxford, UK) was used to capture three-dimensional motion data at a sampling rate of 120 Hz using a Plug-In-Gait marker set [21, 22]. Two Bertec® force platforms (Bertec Corporation, OH, USA) were used to obtain ground reaction forces at a rate of 1080Hz which were synchronized with the motion data. An average of five gait trials at each subject’s self-selected velocity was collected and used for analysis.

Gait analysis was performed using a custom-written code (MatLab TM version7.0 The Mathworks, Inc, Natick, MA, USA). Joint angle trajectories from the Plug-In-Gait model and ground reaction force data were low-pass filtered (Butterworth fourth order, zero phase lag) at 6 and 40 Hz, respectively. The trajectory data from the reflective markers combined with the ground reaction forces were used to calculate the external joint moments and were normalized by body weight and height.

Walking knee joint stiffness was calculated as the change in sagittal plane knee joint moment (M) divided by the change in sagittal plane knee joint angle (θ):

| (1) |

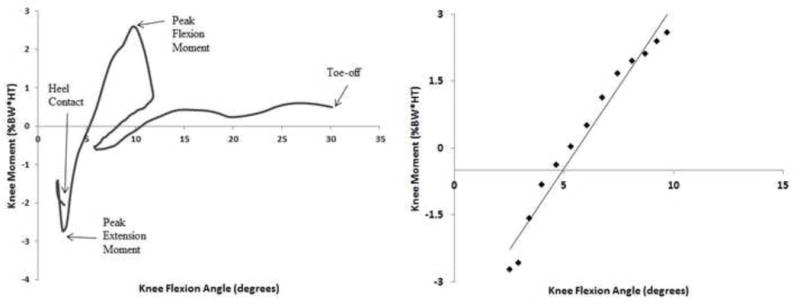

A linear regression curve was fitted to the data points created by plotting the sagittal plane knee joint moment on the Y-axis and the knee flexion angle on the X-axis during the period from peak external knee extension moment to the peak knee joint flexion angle or the peak external knee joint flexion moment, whichever occurred first (Figure 1). This time period corresponded roughly with the first 0–12% of the gait cycle (i.e. weight-acceptance), which began shortly after initial heel contact and included the loading response phase of gait during which the impact of the ground reaction forces are absorbed [23]. Walking knee joint stiffness was then determined as the slope of the fitted curve.

FIGURE 1.

Representative sample of knee flexion angle versus the external knee flexion moment plot (left). Walking knee joint stiffness was calculated as the slope of the linear regression line (right) from peak external knee extension moment to the peak knee flexion angle or peak external knee flexion moment (whichever occurred first) during the weight-acceptance phase of gait.

Self-reported symptoms and functional status

The 24-item Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) was used to gather knee-specific information on symptoms and limitations during performance of functional tasks. The WOMAC is a valid and reliable disease-specific measure of pain, stiffness, and physical function for individuals with knee OA [24]. Higher scores on the WOMAC indicate increased severity of symptoms or functional limitations.

Quadriceps Muscle Strength

The maximum voluntary isometric torque output for the quadriceps was measured using a Biodex System 3 dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems, Shirley, NY, USA). Strength testing was performed with the subject seated and the knee at 60° of flexion. This knee joint position was chosen based on a previous report that patients with knee OA demonstrate reduced knee extension strength at longer muscle lengths, which may not be associated with limitations observed in daily functional activities [25]. The highest maximum torque output of 6 trials was recorded as the quadriceps strength score and was normalized to the subject’s body weight. To verify the reliability of strength measurements, quadriceps strength testing was repeated for 40 participants on two different days which yielded an excellent ICC of 0.96.

Medial Compartment Joint Laxity

Medial compartment joint laxities were measured from stress radiographs using a TELOS stress device (Austin Associates, Fallston, MD, USA) [26]. The x-ray beam was centered approximately 91 cm above the knee joint with the knee flexed to 20 degrees and the patella facing anteriorly. The TELOS device was used to apply a 150 N force to the joint line to produce an opening on the opposite side of the joint. Medial compartment joint laxity was then calculated as the measurement of the medial joint space during a valgus stress test minus the medial joint space during a varus stress test, when the medial joint surfaces were approximated. Excellent reliability (ICC= 0.97 to 0.98) has been previously reported for this protocol [4, 7].

Radiographic Knee Alignment

Knee alignment was determined using a single full-leg, anteroposterior, weight-bearing radiograph [27]. The mechanical axis of the femur was found by drawing a line from the center of the femoral head to the center of the knee. To determine the mechanical axis of the tibia, a second line was drawn from the center of the tibia to the center of the ankle. Knee alignment was then taken to be the angle of intersection between the femoral and tibial axes. Varus and valgus knee malalignment were indicated by values <180° and >180°, respectively. Excellent reliability (ICC = 0.98) has been previously reported for this protocol [28].

Statistical Analysis

Independent sample t-tests and chi-square tests were used to determine group differences in subject characteristics and OA-related risk factors. In addition, differences in biomechanics variables were determined using Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA), adjusting for the effects of gait velocity and gender. Before performing the ANCOVA tests, all variables were evaluated for the assumption of normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The only variable not meeting this assumption was our primary variable of walking knee joint stiffness. Therefore, a log transformation [29] was applied to the walking knee joint stiffness data to meet the assumption of normal distribution. A multiple regression analysis model was also used to determine the contribution of knee flexion angle at heel contact, along with peak knee flexion angle and the peak external knee flexion moment to walking knee joint stiffness in the entire cohort. Separate multiple regression models were used to evaluate the strength of association between walking knee joint stiffness with each OA-related risk factor for the entire cohort. All multiple regression analyses were adjusted for the potential confounding effects of gait speed and gender. A significance level of p<0.05 was selected for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

The knee unstable group was shorter compared to the knee stable group (p<0.01) and had significantly worse (higher) WOMAC subscale scores for pain (p=0.04), physical function (p<0.01) and stiffness (p<0.01). The knee unstable group also walked with a slower self-selected gait velocity (p=0.02) and had greater degrees of varus knee malalignment (p=0.02) compared to the knee stable group (Table 1).

Gait analysis revealed that walking knee joint stiffness was significantly lower in the knee unstable group compared to the knee stable group (p=0.01; Table 2). Additionally, the knee unstable group walked with significantly smaller knee flexion angles at heel contact (p<0.01) but had similar peak knee flexion angles (p=0.50), which together contributed to a significantly greater knee flexion excursion (p<0.01).

TABLE 2.

Summary of group differences in knee joint angle, external knee joint moment and walking knee joint stiffness during the weight-acceptance phase of gait. All analyses were

| Stable (n=35) | Unstable (n=17) | Significance (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knee Flexion Angle at Heel Contact (°) | 5.9 ± 5.1 | 3.6 ± 5.9 | <0.01 |

| Peak Knee Flexion Angle (°) | 17.9 ± 5.8 | 19.1 ± 6.8 | 0.50 |

| Knee Flexion Excursion (°) | 12.3 ± 5.1 | 15.6 ± 6.0 | <0.01 |

| Peak Knee Extension Moment (% BW·HT) | −1.8 ± 0.6 | −1.7 ± 0.6 | 0.83 |

| Peak Knee Flexion Moment (% BW·HT) | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 3.7 ± 1.7 | 0.61 |

| Change in Sagittal Plane Knee Moment (% BW·HT) | 5.1 ± 1.7 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 0.52 |

| Knee Joint Stiffness (% BW·HT/°) | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.01 |

adjusted for the group differences in gait speed and gender.

Regression analysis further revealed that the knee flexion angle at heel contact, along with peak knee flexion angle and the peak external knee flexion moment explained about 74.0% of the variance in walking knee joint stiffness (P < 0.001), after adjusting for the potential effects of gait speed and gender (Table 3). The nature of this relationship was such that a greater knee flexion angle at heel contact, a smaller peak knee flexion angle or a greater peak external knee flexion moment were associated with greater walking knee joint stiffness. On the other hand, quadriceps muscle strength, passive medial compartment joint laxity, and varus knee malalignment were not independently associated with walking knee joint stiffness (Table 4).

Table 3.

Results of the multiple regression analysis used to determine the contribution of knee joint biomechanics during the weight-acceptance phase of gait to walking knee joint stiffness. All analyses were adjusted for the potential effects of gait speed and gender.

| β | SE | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee Flexion Angle at Heel Contact | 0.07 | 0.009 | 0.06,0.09 | < 0.01 |

| Peak Knee Flexion Angle | −0.08 | 0.008 | −0.09, −0.06 | < 0.01 |

| Peak Knee Flexion Moment | 0.18 | 0.025 | 0.13,0.23 | < 0.01 |

| Gait Speed | 0.09 | 0.266 | −0.44,0.62 | 0.74 |

| Gender | −0.07 | 0.084 | −0.24,0.10 | 0.38 |

| Constant | −0.30 | 0.359 | −1.02,0.42 | 0.41 |

beta = standardized coefficient; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval

DISCUSSION

Our initial hypothesis that walking knee joint stiffness would be lower in patients with knee OA and self-reported instability compared to their knee stable counterparts was supported by the data. As increased walking knee joint stiffness has been previously proposed as a compensatory strategy to counteract the deleterious effects of increased knee joint laxity in patients with OA [13], walking with lower knee joint stiffness in our knee unstable group suggests an absent compensatory adaptation to control medial compartment joint laxity during gait. However, given the cross-sectional design of our study, the observed findings garner limited information regarding the temporal nature of the relationship between self-reported knee joint instability and walking knee joint stiffness. Additional studies are needed to clarify whether decreased walking knee joint stiffness is the underlying cause of episodic knee joint instability or if a history of instability leads to volitional changes in movement patterns that reduce walking knee joint stiffness.

Also consistent with our initial hypothesis, the significantly greater knee flexion excursions during the weight-acceptance phase of gait was found to be a major contributor to reduced walking knee joint stiffness in the knee unstable group. The findings of our regression analysis revealed that knee flexion angle at heel contact, along with peak knee flexion angle and peak knee flexion moment during the weight-acceptance phase of gait explain about 74% of the variance in walking knee joint stiffness. Given that no group differences were observed for peak knee flexion angle or peak knee flexion moment, the smaller knee flexion angles at heel contact appears to be the primary reason for the lower walking knee joint stiffness in the knee unstable group. Alternatively, it could also be argued that smaller knee flexion angles at heel contact could be the direct cause of episodic instability that subsequently resulted in decreased walking knee joint stiffness. Regardless of the underlying mechanism, gait retraining strategies aimed at achieving greater knee flexion angles at heel contact and reducing knee flexion excursion warrant future evaluation as potential intervention targets for patients with knee OA and self-reported instability.

The findings of our study also demonstrated that there were no group differences in passive medial compartment joint laxity or quadriceps strength between the knee stable and knee unstable groups. Additionally, no significant associations were observed between medial compartment joint laxity and walking knee joint stiffness. Despite a previous report of an inverse association between quadriceps strength and walking knee joint stiffness in patients after total knee arthroplasty [30], quadriceps strength was also not independently associated with walking knee joint stiffness. Together, these findings suggest that increased walking knee joint stiffness and self-reported knee instability are most likely the result of more complex mechanisms than just increased medial compartment joint laxity or quadriceps muscle weakness. Although we did find greater varus malalignment in our knee unstable group compared to the knee stable group, varus malalignment was also not independently associated with walking knee joint stiffness. This finding is not surprising as varus malalignment is more likely to contribute to alterations in the frontal plane biomechanics during gait, while walking knee joint stiffness is a sagittal plane measure of knee joint function.

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. It is acknowledged that gait speed plays an important role in determining walking knee joint stiffness [13]. Our subjects with self-reported instability walked with slower self-selected gait speeds which could have contributed to their lower walking knee joint stiffness. However, a post-hoc analysis of the relationship between gait speed and walking knee joint stiffness revealed that the two variables were not associated (Pearson’s r = −0.13, p=0.31). Similarly, the knee unstable group had a much larger proportion of females compared to the knee stable group (65% versus 37%). As such, the potential confounding effect of gait speed and gender on walking knee joint were statistically controlled for in all analyses. It is also recognized that participants’ use of their usual walking shoes could have affected their walking knee joint stiffness due to differences in shoe materials and structure. Additionally, the knee unstable group in our study had significantly higher (worse) self-reported knee joint stiffness scores on the WOMAC despite having lower walking knee joint stiffness compared to the knee stable group. This apparent discrepancy may be due to the fact that these measures evaluate different aspects of knee joint stiffness in patients with knee OA [14] which also merits further investigation.

CONCLUSION

Patients with knee OA and self-reported instability appear to walk with lower knee joint stiffness compared to their counterparts without instability. Additionally, walking knee joint stiffness appears to be independent of the commonly observed OA-related risk factors of quadriceps weakness, passive medial compartment joint laxity, and varus knee malalignment. Considering the cross-sectional design of the current study, however, whether increased walking knee joint stiffness is the direct cause of episodic knee joint instability in patients with knee OA remains unknown and warrants further investigation.

Highlights.

Self-reported knee instability was associated with lower knee joint stiffness.

Increased knee flexion excursion was associated with lower knee joint stiffness.

Lower heel-contact knee flexion was also associated with lower knee joint stiffness.

Quadriceps muscle strength was not associated with walking knee joint stiffness.

Medial compartment laxity was also not associated with walking knee joint stiffness.

Acknowledgments

This study was approved by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant 1-R01-AR048760) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institute Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health career development award (K12 HD055931).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest regarding the work described in the current manuscript.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. Reports of joint instability in knee osteoarthritis: its prevalence and relationship to physical function. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:941–6. doi: 10.1002/art.20825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Esch M, Knoop J, van der Leeden M, Voorneman R, Gerritsen M, Reiding D, et al. Self-reported knee instability and activity limitations in patients with knee osteoarthritis: results of the Amsterdam osteoarthritis cohort. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:1505–10. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsey DK, Briem K, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A mechanical theory for the effectiveness of bracing for medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2398–407. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewek MD, Rudolph KS, Snyder-Mackler L. Control of frontal plane knee laxity during gait in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2004;12:745–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma L, Lou C, Felson DT, Dunlop DD, Kirwan-Mellis G, Hayes KW, et al. Laxity in healthy and osteoarthritic knees. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:861–70. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<861::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wada M, Imura S, Baba H, Shimada S. Knee laxity in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Brit J Rheumatol. 1996;35:560–3. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.6.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88:1506–16. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitt LC, Rudolph KS. Influences on knee movement strategies during walking in persons with medial knee osteoarthritis. Athritis Rheum. 2007;57:1018–26. doi: 10.1002/art.22889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitt LC, Rudolph KS. Muscle stabilization strategies in people with medial knee osteoarthritis: the effect of instability. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1180–5. doi: 10.1002/jor.20619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felson DT, Niu J, McClennan C, Sack B, Aliabadi P, Hunter DJ, et al. Knee buckling: prevalence, risk factors, and associated limitations in function. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:534–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrokhi S, Voycheck CA, Klatt BA, Gustafson JA, Tashman S, Fitzgerald GK. Altered tibiofemoral joint contact mechanics and kinematics in patients with knee osteoarthritis and episodic complaints of joint instability. Clin Biomech. 2014;29:629–35. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Childs JD, Sparto PJ, Fitzgerald GK, Bizzini M, Irrgang JJ. Alterations in lower extremity movement and muscle activation patterns in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech. 2004;19:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeni JA, Jr, Higginson JS. Dynamic knee joint stiffness in subjects with a progressive increase in severity of knee osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech. 2009;24:366–71. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon SJ, Hinman RS, Creaby MW, Kemp G, Crossley KM. Knee joint stiffness during walking in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:38–44. doi: 10.1002/acr.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis RB, DeLuca PA. Gait characterization via dynamic joint stiffness. Gait Posture. 1996;4:224–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrokhi S, O’Connell M, Gil AB, Sparto PJ, Fitzgerald GK. Altered gait characteristics in individuals with knee osteoarthritis and self-reported knee instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45:351–9. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Gil AB, Wisniewski SR, Oddis CV, Irrgang JJ. Agility and perturbation training techniques in exercise therapy for reducing pain and improving function in people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2011;91:452–69. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–49. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteoarthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irrgang JJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Wainner RS, Fu FH, Harner CD. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1132–45. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis RB, Ounpuu S, Tyburski D, Gage JR. A gait analysis data collection and reduction technique. Hum Movement Sci. 1991;10:575–87. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari A, Benedetti MG, Pavan E, Frigo C, Bettinelli D, Rabuffetti M, et al. Quantitative comparison of five current protocols in gait analysis. Gait Posture. 2008;28:207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry J, Burnfield JM. Gait analysis: normal and pathological function. 2nd. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins NJ, Misra D, Felson DT, Crossley KM, Roos EM. Measures of knee function: International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Knee Evaluation Form, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Physical Function Short Form (KOOS PS), Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily-Living Scale (KOS-ADL), Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, Oxford Knee Score (OKS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Activity Rating Scale (ARS), and Tegner Activity Score (TAS) Arthrit Care Res. 2011;63:S208–S28. doi: 10.1002/acr.20632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher N, Pendergast D. Reduced muscle function in patients with osteoarthritis. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1997;29:213–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore TM, Meyers MH, Harvey JP., Jr Collateral ligament laxity of the knee. Long-term comparison between plateau fractures and normal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:594–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreland JR, Bassett LW, Hanker GJ. Radiographic analysis of the axial alignment of the lower extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:745–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinman RS, May RL, Crossley KM. Is there an alternative to the full-leg radiograph for determining knee joint alignment in osteoarthritis? Arthrit Care Res. 2006;55:306–13. doi: 10.1002/art.21836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keene ON. The log transformation is special. Stat Med. 1995;14:811–9. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGinnis K, Snyder-Mackler L, Flowers P, Zeni J. Dynamic joint stiffness and co-contraction in subjects after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Biomech. 2013;28:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]