Abstract

Objectives To describe how the methodological quality of primary studies is assessed in systematic reviews and whether the quality assessment is taken into account in the interpretation of results.

Data sources Cochrane systematic reviews and systematic reviews in paper based journals.

Study selection 965 systematic reviews (809 Cochrane reviews and 156 paper based reviews) published between 1995 and 2002.

Data synthesis The methodological quality of primary studies was assessed in 854 of the 965 systematic reviews (88.5%). This occurred more often in Cochrane reviews than in paper based reviews (93.9% v 60.3%, P < 0.0001). Overall, only 496 (51.4%) used the quality assessment in the analysis and interpretation of the results or in their discussion, with no significant differences between Cochrane reviews and paper based reviews (52% v 49%, P = 0.58). The tools and methods used for quality assessment varied widely.

Conclusions Cochrane reviews fared better than systematic reviews published in paper based journals in terms of assessment of methodological quality of primary studies, although they both largely failed to take it into account in the interpretation of results. Methods for assessment of methodological quality by systematic reviews are still in their infancy and there is substantial room for improvement.

Introduction

Critical appraisal of the methodological quality of primary studies is an essential feature of systematic reviews.1-3 A recent review showed that lack of adherence to a priori defined validity criteria may help explain why primary studies on the same topic provide different results.4 Some key issues still remain unresolved: which checklists and scales are the ideal approaches5 and how the results of quality assessment in a systematic review should be handled in the analysis and interpretation of results.6-10

We compared the approaches used for quality assessment of primary studies by Cochrane systematic reviews with systematic reviews published in paper based journals. We determined how quality assessment is used and whether systematic reviews consider quality assessment in their results.

Methods

We sampled systematic reviews from two databases in the Cochrane Library: the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, which includes reviews prepared by review groups of the Cochrane Collaboration; and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), which selects systematic reviews published in peer reviewed journals on the basis of their adherence to a few methodological requirements.11

We stratified all 1297 Cochrane systematic reviews published in issue 1, 2002, of the Cochrane Library by type of intervention (six levels: drugs; rehabilitation or psychosocial; prevention or screening; surgery or radiotherapy intervention; communication, organisational, or educational; other) and by Cochrane review group (50 levels). We used a computer generated randomisation scheme to select at least 50% of the systematic reviews in each cell. Our final sample represented 62.4% (n = 809) of the Cochrane reviews. The paper based systematic reviews were extracted from DARE, including all systematic reviews published in 2001 registered up to November 2002.

Data extraction form

We assessed the systematic reviews by using an ad hoc data extraction form. We developed this form by taking into account published reports on the quality assessment of trials included in systematic reviews.1,2,4-10,12-28

We did not aim at standardised operational definitions of the quality measures but accepted at face value what was reported by the authors of individual studies. As a common taxonomy for quality assessment does not exist, we used a large number of descriptive quality components to capture as many of the different definitions as possible.

For each systematic review we sought general information (title, authors, publication date, type of intervention, and presence of a meta-analysis). We then evaluated what authors reported in the methods section of their review for quality assessment. In particular, we tried to ascertain whether authors stated they would have assessed the quality and how (scale or checklist, components studied, composite score) and in what way they planned to use the quality assessment (for example, as exclusion criteria, for sensitivity analysis). See bmj.com for a summary version of the data extraction form.

We then evaluated how authors assessed quality. We recorded if trials were combined in a quantitative meta-analysis; if the quality was evaluated; if scales, checklists, and scores were used; and how the quality was formally incorporated. Assessors judged whether an attempt had been made to incorporate the quality assessment in the results, either qualitatively or quantitatively.

We purposely did not make our operationalised definition of qualitative too stringent. If authors made some comments or discussed the results with reference to the quality of trials then we considered this sufficient to classify the systematic review as having incorporated qualitatively the quality assessment.

Our definition of quantitative was more stringent and included the carrying out of a sensitivity or subgroup analysis (with quality as a stratifying factor) and use of a quality score as a weight or factor for cumulative meta-analysis or metaregression.

Data extraction

We developed a draft of an extraction checklist and piloted it on 40 randomly selected Cochrane reviews. The checklist was revised and an instruction manual prepared. The checklist was further tested on another random sample of 130 systematic reviews, and further refinements were incorporated. Inter-rater agreement, based on a random sample of 5% of the Cochrane reviews and paper based reviews (48 reviews), was high. Inter-rater reliability was moderate to perfect (percentage mean agreement 94, range 71.1-100; prevalence and bias adjusted κ statistic mean 0.80, range 0.40-1.00).

Twelve pairs of investigators independently extracted the data. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and, when necessary, centrally reviewed.

Statistical analysis

Owing to the frequent imbalance of marginals in our contingency matrix, we used a prevalence and bias adjusted κ statistic to assess inter-rater reliability.29,30 We report confidence intervals of differences between proportions and P values of χ2 tests.

Results

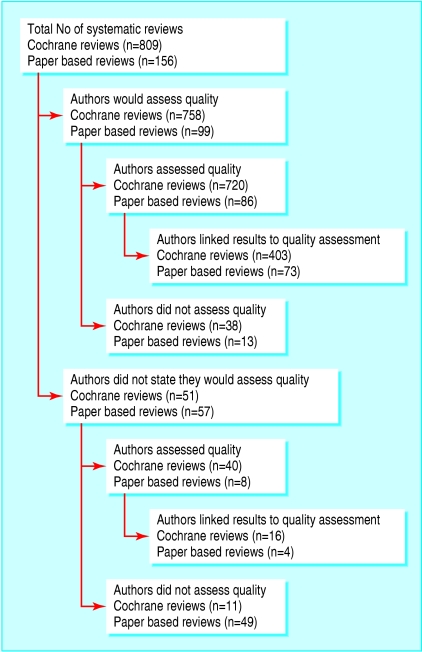

We analysed 965 systematic reviews: 809 Cochrane reviews and 156 reviews published in paper based journals (figure). Quality assessment was assessed in 854 (88.5%) of the reviews and was more often carried out in Cochrane reviews than in paper based reviews (93.9% v 60.3%, P < 0.0001; table 1). The same was true when we compared the proportions of reviews using quality assessment in an informal fashion (90.5% v 51.9%; P < 0.0001; table 2). The formal approaches most used by both types of review were exclusion criteria (12%), sensitivity analysis (10%), exploration of heterogeneity (8%), and subgroup analysis (4%).

Figure 1.

Flow of systematic reviews through trial

Table 1.

Distribution of three main quality assessment related variables investigated in study according to Cochrane systematic reviews and systematic reviews published in paper based journals. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Variable | Cochrane systematic reviews (n=809) | Paper based systematic reviews (n=156) | Difference between proportions (95% CI) | P value (χ2 test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors would carry out quality assessment | 758 (93.7) | 99 (63.5) | 30.2 (22.5 to 38.0) | <0.0001 |

| Quality assessment carried out | 760 (93.9) | 94 (60.3) | 33.6 (25.8 to 41.5) | <0.0001 |

| Quality assessment linked to results | 419 (51.8) | 77 (49.4) | 2.4 (−6.1 to 11.0) | 0.5777 |

Table 2.

Summary of approaches to quality assessment and formal quantitative analyses related to quality assessment used in Cochrane systematic reviews and systematic reviews published in paper journals. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Approaches used to incorporate quality assessment* | Cochrane systematic reviews (n=809) | Paper based systematic reviews (n=156) | Cochrane and paper based reviews | Difference between proportions (95% CI) | P value (χ2 test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal: | |||||

| General comment | 732 (90.5) | 81 (51.9) | 813 (95) | 38.6 (30.5 to 46.7) | <0.0001 |

| Formal: | |||||

| Exclusion criteria | 102 (12.6) | 9 (5.8) | 111 (12) | 6.8 (2.5 to 11.2) | 0.0142 |

| Exploration of heterogeneity | 63 (7.8) | 11 (7.1) | 74 (8) | 0.7 (−3.7 to 5.2) | 0.7517 |

| Subgroup analysis | 29 (3.6) | 8 (5.1) | 37 (4) | −1.5 (−5.2 to 2.1) | 0.3580 |

| Sensitivity analysis | 89 (11.0) | 9 (5.8) | 98 (10) | 5.2 (1.0 to 9.5) | 0.0476 |

| Weighting of estimates | 1 (0.1) | 0 | — | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.4) | 0.6604 |

| Cumulative meta-analysis | 1 (0.1) | 0 | — | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.4) | 0.6604 |

More than one answer possible.

The quality components most frequently assessed were, in decreasing order, allocation concealment, blinding, and losses to follow-up. The difference between Cochrane reviews and paper based reviews for these and intention to treat analysis significantly favoured Cochrane reviews (table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of quality components and quality scales most used in Cochrane systematic reviews and systematic reviews published in paper based journals analysed in study. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Variable | Cochrane systematic reviews (n=809) | Paper based systematic reviews (n=156) | Difference between proportions (95% CI) | P value (χ2 test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality components*: | ||||

| Allocation concealment | 639 (79.0) | 37 (23.7) | 55.3 (48.0 to 62.5) | <0.0001 |

| Any type of blinding | 604 (74.7) | 64 (41.0) | 33.7 (25.4 to 41.9) | <0.0001 |

| Generation of allocation sequence | 209 (25.8) | 26 (16.7) | 9.1 (2.6 to 15.8) | 0.0146 |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | 142 (17.6) | 17 (10.9) | 6.7 (1.1 to 12.2) | 0.0402 |

| Description of outcomes | 110 (13.6) | 14 (9.0) | 4.6 (−0.5 to 9.7) | 0.1142 |

| Intention to treat analysis | 240 (29.7) | 19 (12.2) | 17.5 (11.5 to 23.5) | <0.0001 |

| Sample size | 99 (12.2) | 24 (15.4) | −3.2 (−9.2 to 3.0) | 0.2805 |

| Losses to follow-up | 561 (69.3) | 52 (33.3) | 36.0 (28.0 to 44.1) | <0.0001 |

| Quality scale: | ||||

| Schulz | 37 (4.6) | 2 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.0 to 5.6) | 0.0560 |

| Jadad | 84 (10.4) | 29 (18.6) | −8.4 (−14.9 to −2.0) | 0.0025 |

| Cochrane Group | 133 (16.4) | 0 (0) | 16.4 (13.9 to 19.0) | <0.0001 |

| Other | 35 (4.3) | 20 (12.8) | −8.5 (−13.9 to −3.1) | <0.0001 |

More than one answer possible.

The most commonly used quality scale was the Jadad scale (n = 113, 11.7%; table 3). Cochrane reviews used the scale less often than paper based reviews. In 65.0% (n = 526) of Cochrane reviews and 48.1% (n = 75) of paper based reviews, authors carried out the quality assessment using single components rather than a formal scale.

No significant differences emerged when Cochrane reviews and paper based reviews were analysed separately by type of intervention assessed—for example, drug compared with non-drug interventions.

Utilisation of quality assessment

We found that 496 systematic reviews (51.4%) linked quality to the interpretation of results, with no difference in the proportions of Cochrane reviews and paper based reviews (51.8% v 49.4%, P = 0.58; table 1). This also held true for the subgroup analysis of drug compared with non-drug interventions.

Is quality assessment carried out as stated?

The authors of Cochrane reviews were more likely than those of paper based reviews to state that they would assess quality (93.7% v 63.5%) yet did not always do so (table 1). About 5% of systematic reviews in each group carried out quality assessment despite not being explicitly stated in the methods. Finally, only 328 (33.9%) of the systematic reviews formally specified how they planned to use the quality assessment in the methods (for example, for sensitivity analysis, exclusion criteria): 36.0% (n = 291) of Cochrane reviews and 23.7% (n = 37) of paper based reviews (P = 0.79).

Discussion

More than 50% of systematic reviews (both Cochrane reviews and reviews based in paper articles) did not specify in the methods whether and how they would use quality assessment in the analysis and interpretation of results. Cochrane reviews fared better than paper based reviews in carrying out quality assessment but were equally unsuccessful in taking it into account.

Since 1987 several authors have explored the extent to which systematic reviews and meta-analyses incorporate quality assessment into the results, with unsatisfactory findings.22,31-34 Moher et al analysed 240 systematic reviews19: quality assessment was carried out more often in Cochrane reviews than in reviews published in paper based journals (36/36, 100% v 78/204, 38%; P < 0.001), although only 29 took such assessment into account during their analysis (paper based reviews 27/78 34% v Cochrane reviews 2/36 6%; P < 0.001).

During the past 15 years research has concentrated on two main issues: which components of the quality assessment (for example, allocation concealment) are predictive of valid results and what tool (scales or checklists) best assesses quality. In 2003 Egger et al found that allocation concealment and double blinding were strongly related to treatment effects.4,20,35 Despite the dozens of quality scales and checklists that have been proposed,5,7,18 the answer is still unclear and many doubt that a generic quality assessment tool that would prove valid in all cases can ever be found. In our study the most frequently used tool was the Jadad scale, a tool that has been criticised for its low sensitivity and that does not consider allocation concealment because it was developed before the importance of concealment was established.21 Moreover, less attention has been paid to explore how quality can be used in the interpretation of the results of systematic reviews.8,9,13,36

As Cochrane reviews are preceded by a published protocol and the Cochrane handbook mandates that some form of quality assessment of primary studies is to be done,37 it is not surprising that authors of Cochrane reviews state that they will carry out quality assessment and do so. Yet when it comes to the more complex, yet potentially relevant, aspect of incorporating quality into the results, Cochrane reviews fared no better than their paper based counterpart.

These findings may have several explanations. That Cochrane reviews provide more details may be due to the absence of limitations on space in electronic publications; however, most of the medical journals now publish a web version of their papers, with different space restrictions. We investigated this potential of the electronic versions but found that none of the paper based reviews was supplemented with an electronic appendix of quality assessment. It is also possible that authors are unaware of, or that editors are not interested in, publishing extensive electronic versions. Moreover, most authors of paper based articles may be aware of space limitations imposed by journals and thus omit details of quality assessment because they believe that they not are relevant to their results. This could be a reflection of a bad practice: a more common use of unplanned outcome dependent subgroup analyses. Where subgroup analyses are not predefined, the risk exists that data may have been dredged in search of a significant result.38 Cochrane systematic reviews are, at least in principle, protected against post hoc analyses through the preliminary publication of a detailed study protocol.

Limitations of the study

One limitation of our study is that the Cochrane reviews were published between 1995 and 2002, whereas the paper based articles were first published in 2001. Although older, the Cochrane reviews still fared better for frequency of quality assessment. The Cochrane reviews were, however, remiss in their efforts to incorporate the quality assessment findings in the presentation and interpretation of results. We believe that this difference in publication dates did not affect our results because between 1995 and 2000 no major methodological advances or new consensus emerged in the literature on systematic reviews. Another limitation is whether DARE39 was an appropriate source from which to sample paper based articles. This is a legitimate concern as it may have led to the selection of a control group with better than average quality. Any selection bias would move our estimate towards the null effect or would minimise the difference between the two types of reviews. Thus, our results could be understated.

A third possible limitation is that incomplete reporting might have influenced our assessment. Evidence, however, suggests that what is reported about important aspects of the conduct of a study typically do reflect what is actually done.40,41

Finally, we assessed quality assessment using a checklist that had been developed ad hoc. Although the lack of validation may be criticised, we believe that the items have good face validity: we attempted to reduce assessors' subjectivity, and the inter-rater reliability was acceptably high. We did have trouble with the classification of quality items, tools, and approaches, as there are innumerable ways to define study quality.7,20 It is possible that we recorded quality data with slightly different meanings from those intended by the authors of the studies. Given that almost all systematic reviews were incomplete in their reporting and given the narrative nature of the quality assessment, it is likely that our checklist may have had decreased ability to reflect what authors truly wanted to do and did. It was beyond the scope of our study to assess the appropriateness of the methods chosen for quality assessment by the authors.

Conclusions

Within the Cochrane Collaboration there is room for better standardisation of approaches to quality assessment. The Cochrane handbook should provide clearer guidelines on how to do it. Less clear is how to improve quality assessment in articles published in paper based journals. For such reviews, improvement may only come once a consensus of methodology for systematic reviews has been decided. Peer reviewers and editors should scrutinise systematic reviews to ensure consistency among the various sections and to avoid outcome dependent analyses.

We believe that more research is needed to understand how best to assess and incorporate the methodological quality of primary studies into the results of systematic reviews. Progress towards the necessary improvements highlighted by the results of this study may come from two international meetings planned in May and June 2005 that will be dedicated to, respectively, an improvement of the current section of the Cochrane handbook on quality assessment in systematic reviews and a revision of the QUOROM statement.2

What is already known on the topic

Appraisal of the methodological quality of primary studies is essential in systematic reviews

No consensus exists on the ideal checklist and scale for assessing methodological quality

The Cochrane Collaboration encourages a simple approach to quality assessment based on individual components such as allocation concealment

What this study adds

Approaches to quality assessment of primary studies by systematic reviews are heterogeneous and reflect a lack of consensus on best practice

Cochrane reviews assess methodological quality more often than paper based reviews

Both types of review failed to link the quality assessment to the interpretation of results in almost half of cases

Supplementary Material

Summary version of data extraction form is on bmj.com

Summary version of data extraction form is on bmj.com

We thank Sabrina Bidoli and Sheila Iacono for their help with data entry and organisational activities; Simone Mangano and Luca Clivio for their support in developing the database; the other members of the Cochrane Collaboration who commented on the study and our interpretation of it when it was presented at the International X and XI Cochrane Colloquia (Stavanger, Norway, 2002 and Barcelona, Spain, 2003); and David Moher, Peter Tugwell, Keith O'Rourke, and Dave Sackett for commenting on an earlier version of this paper.

Contributors: LPM, ET, RD'A, and AL wrote the protocol of the study and RD'A and AL developed the grant application to complete this project. ET and LPM coordinated the project, participated in the quality assessment, data extraction, database development, and data entry. LC, IM, and RD'A participated in the quality assessment, data extraction, and data entry. RD'A, LPM, and IM completed the data analyses. All authors provided feedback on earlier versions of the paper. LPM, RD'A, and AL took primary responsibility for writing the manuscript, which was revised by coauthors. AL is guarantor for the paper. Metaquality Study Group: the following researchers were members of the Milano master course in systematic reviews and contributed to the study in the pilots, reading and quality assessment of systematic reviews, data extraction, and data entry: Battaggia Alessandro, Bianco Elvira, Calderan Alessandro, Colli Agostino, Ferri Marica, Fraquelli Mirella, Girolami Bruno, Marchioni Enrico, Mezza Elisabetta, Piccoli Giorgina, Vignatelli Luca, Monaco Giuseppe, Morganti Carla, Franceschini Roberta, Bermond Francesca, Cevoli Sabina, Franzoso Federico, Ruggeri Marco, Joppi Roberta, Minesso Elisabetta, Lomolino Grazia, and Bellù Roberto.

Funding: Ministero della Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca, Rome, Italy (protocol grant No 2002061749 COFIN 2002).

Competing interests: All members of the research team are members of the Cochrane Collaboration. ET, IM, RD'A, LC, and AL are authors of Cochrane reviews published in the Cochrane Library. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cochrane Collaboration.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Juni P, Altman DG, Matthias E. Assessing the quality of randomised controlled trials. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context, 2nd ed. London: BMJ Books, 2001.

- 2.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet 1999;354: 1896-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. Guidelines for reading literature reviews. CMAJ 1988;138: 697-703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egger M, Juni P, Bartlett C, Holenstein F, Sterne J. How important are comprehensive literature searches and the assessment of trial quality in systematic reviews? Empirical study. Health Technol Assess 2003;7: 1-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 1999;282: 1054-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT, eds. Assessment of study quality. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2.2 [updated March 2004]; Section 6. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Chichester: Wiley, 2004. (accessed 1 Apr 2005).

- 7.Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Boers M, van den Brandt PA. The art of quality assessment of RCTs included in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54: 651-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenland S, O'Rourke K. On the bias produced by quality scores in meta-analysis, and a hierarchical view of proposed solutions. Biostatistics 2001;2: 463-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Detsky AS, Naylor CD, O'Rourke K, McGeer AJ, L'Abbe KA. Incorporating variations in the quality of individual randomized trials into meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45: 255-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Jadad AR, Tugwell P. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials. Current issues and future directions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1996;12: 195-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petticrew M, Song F, Wilson P, Wright K. Quality-assessed reviews of health care interventions and the database of abstracts of reviews of effectiveness (DARE). NHS CRD review, dissemination, and information teams. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1999;15: 671-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 2001;323: 42-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenland S. Invited commentary: a critical look at some popular meta-analytic methods. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140: 290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linde K, Scholz M, Ramirez G, Clausius N, Melchart D, Jonas WB. Impact of study quality on outcome in placebo-controlled trials of homeopathy. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52: 631-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 1998;352: 609-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med 2001;135: 982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273: 408-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials 1995;16: 62-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Tugwell P, Moher M, Jones A, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomised trials: implications for the conduct of meta-analyses. Health Technol Assess 1999;3: 1-98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balk EM, Bonis PA, Moskowitz H, Schmid CH, Ioannidis JP, Wang C, et al. Correlation of quality measures with estimates of treatment effect in meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2002;287: 2973-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17: 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jadad AR, Cook DJ, Jones A, Klassen TP, Tugwell P, Moher M, et al. Methodology and reports of systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a comparison of Cochrane reviews with articles published in paper-based journals. JAMA 1998;280: 278-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996;276: 637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalmers TC, Smith H Jr, Blackburn B, Silverman B, Schroeder B, Reitman D, et al. A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials 1981;2: 31-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark HD, Wells GA, Huet C, McAlister FA, Salmi LR, Fergusson D, et al. Assessing the quality of randomized trials: reliability of the Jadad scale. Control Clin Trials 1999;20: 448-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown SA. Measurement of quality of primary studies for meta-analysis. Nurs Res 1991;40: 352-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho MK, Bero LA. Instruments for assessing the quality of drug studies published in the medical literature. JAMA 1994;272: 101-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colditz GA, Miller JN, Mosteller F. How study design affects outcomes in comparisons of therapy. I: medical. Stat Med 1989;8: 441-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46: 423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lantz CA, Nebenzahl E. Behavior and interpretation of the kappa statistic: resolution of the two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49: 431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulrow CD. The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med 1987;106: 485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shea B, Moher D, Graham I, Pham B, Tugwell P. A comparison of the quality of Cochrane reviews and systematic reviews published in paper-based journals. Eval Health Prof 2002;25: 116-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jadad AR, Moher M, Browman GP, Booker L, Sigouin C, Fuentes M, et al. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on treatment of asthma: critical evaluation. BMJ 2000;320: 537-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAlister FA, Clark HD, van Walraven C, Straus SE, Lawson FM, Moher D, et al. The medical review article revisited: has the science improved? Ann Intern Med 1999;131: 947-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juni P, Egger M. Allocation concealment in clinical trials. JAMA 2002;287: 2408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tritchler D. Modelling study quality in meta-analysis. Stat Med 1999;18: 2135-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT, eds. Developing a protocol. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2.2 [updated March 2004]; Section 3. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Chichester: Wiley, 2004. (accessed 1 Apr 2005).

- 38.Counsell CE, Clarke MJ, Slattery J, Sandercock PA. The miracle of DICE therapy for acute stroke: fact or fictional product of subgroup analysis? BMJ 1994;309: 1677-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DARE—a database of `high quality reviews' or `quality assessed reviews'? University of York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2004.

- 40.Altman DG, Dore CJ. Randomisation and baseline comparisons in clinical trials. Lancet 1990;335: 149-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liberati A, Himel HN, Chalmers TC. A quality assessment of randomized control trials of primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1986;4: 942-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.