Abstract

Several clinical trials have evaluated naltrexone as a treatment for alcohol use disorders, but few have focused on women. The aim of this review was to systematically review and summarize the evidence regarding the impact of naltrexone compared to placebo for attenuating alcohol consumption in women with an alcohol use disorder (AUD).

A systematic review was conducted using PubMed, Cochrane, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Alcohol Studies Database to identify relevant peer-reviewed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published between January 1990 and August 2016.

Seven published trials have evaluated the impact of naltrexone on drinking outcomes in women distinct from men. 903 alcohol-dependent or heavy drinking women were randomized to receive once daily oral or depot (injectable) naltrexone or placebo with/without behavioral intervention. Two studies examining the quantity of drinks per day observed trends toward reduction in drinking quantity among women who received naltrexone vs. placebo. The 4 studies examining the frequency of drinking had mixed results, with one study showing a trend that favored naltrexone, two showing a trend that favored placebo, and one that showed no difference. Two of the three studies examining time to relapse observed trends that tended to favor naltrexone for time to any drinking and time to heavy drinking among women who received naltrexone vs. placebo.

While the growing body of evidence suggests a variety of approaches to treat alcohol use disorders (AUD), the impact of naltrexone to combat AUD in women is understudied. Taken together, the results suggest that naltrexone may lead to modest reductions in quantity of drinking and time to relapse, but not on the frequency of drinking in women. Future research should incorporate sophisticated study designs that examine gender differences and treatment effectiveness among those diagnosed with an AUD and present data separately for men and women.

Keywords: naltrexone, alcohol, women

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, alcoholism is a prevalent and costly public health issue with women representing the fastest-growing population of alcohol users [Krystal et al., 2001; NCADD, 2015]. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2016) estimates that 5.7 million women over 18 years in the US have an alcohol use disorder (AUD); the term used to describe problem drinking and is classified as mild, moderate or severe [NIAAA, 2016; SAMHSA, 2012; NIH, 2015]. Consequently, alcohol use disorders are the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the US [Mokdak et al., 2004; Stahre et al., 2014].

Multiple psychosocial, behavioral, and pharmacotherapy interventions have been shown to be effective in treating an AUD, however, the relapse rate approximates 70% [Moos & Moos, 2006]. The primary treatment goals for an AUD are abstinence from drinking or reduction in heavy drinking [Srisurapanont & Jarusuraisin, 2005; Maisel et al., 2012; Jonas et al., 2014]. Thus, women present a special subset of an AUD as a result of physiologic status, psychosocial factors, and genetic considerations [Mann et al., 1992; Mann et al., 2005; Ponce et al., 2005; Diehl et al., 2007; Greenfield et al., 2010]. Women who consume an extreme amount of alcohol can subject themselves to immediate effects that can increase their risk of harmful health conditions [CDC, 2015]. Likewise, excessive alcohol consumption can lead to the development of chronic diseases and other serious problems such as developing alcohol dependence or alcoholism [CDC, 2015]. While several medications (i.e., naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram) have been used to reduce heavy drinking and increase days of alcohol abstinence in drinkers, the efficacy of these interventions varies considerably [Streeton & Whelan, 2001; Srisurapanont & Jarusuraisin, 2005; Carmen et al., 2004; Maisel et al., 2012; Jonas et al., 2014].

As previously mentioned, naltrexone is a prescription medication that has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and promoted for use in AUD populations [Garbutt et al., 2005; Hernandez-Avila et al., 2006; Roozen et al., 2007]. Naltrexone acts to decrease alcohol cravings and reduce the reinforcing effects of alcohol consumption by blocking opioid-mediated increases in central dopamine release [Gianoulakis, 2001]. Administration options include oral medication once per day or a once-a-month injectable [Garbutt et al., 2005; Hernandez-Avila et al., 2006; Roozen et al., 2007]. While the optimal dose of naltrexone is not known, most studies used 50mg/day (range 50mg–150mg). Moreover, studies have reported that naltrexone is more effective than other pharmacotherapies particularly when combined with behavioral treatment [Anton et al., 2006; O’Malley et al., 2007]. However, clinical trials evaluating combinations of naltrexone and behavioral interventions have demonstrated mixed results [Anton et al., 2006; Ponce et al., 2005; Lovallo et al., 2012; Garbutt et al., 2014]. Most importantly, gender differences (i.e., absorption, genetics, vulnerability, etc.) underscore the need to evaluate the impact of specific treatment options for AUDs in women. While recent systematic reviews suggest slight benefit from naltrexone [Kranzler & Van kirk, 2006; Jonas et al., 2014; Donoghue et al., 2015], they do not specifically address variables specific to naltrexone treatment in women. Against this background, the objective of this paper is to systematically review and summarize the evidence regarding the impact of naltrexone vs. placebo for attenuating alcohol consumption in women with an alcohol use disorder (AUD).

METHODS

Search Strategy

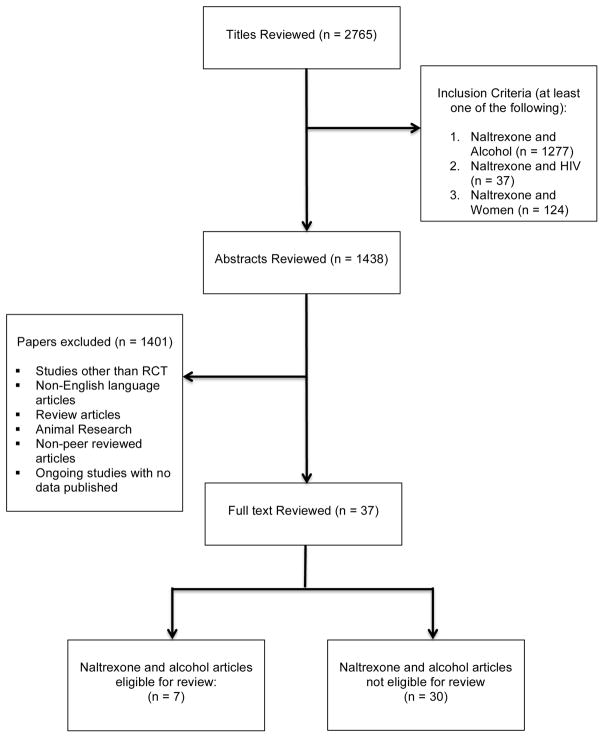

From January 1990 – August 2016, we queried online databases PubMed, Cochrane, Web of Science, CINAHL, and the Alcohol Studies Database for peer-reviewed original human research (Figure 1). A search was undertaken using the following search terms: naltrexone AND (alcohol; OR alcohol dependence; alcohol use disorders; hazardous drinking; heavy drinking; binge drinking; alcohol consumption) AND (women; OR female). Additional searches of Google Scholar and references of identified secondary literature were also carried out. This review included all relevant randomized controlled trials (RCT). The first author (SC) screened all eligible articles for relevance using titles and abstracts. Additionally, three researchers (GC, CC, and RC) independently reviewed eligible papers.

Figure 1.

This review included trials that evaluated the impact of naltrexone on drinking outcomes in women alone or distinct from men. This review used the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: (1) must include a RCT design, (2) published in English or capable of being translated, (3), published between 1990 to 2016, (4) intervention was oral or injectable naltrexone with or without behavioral intervention, (5) assessed a measurable drinking outcome, (6) study must present results for women alone or distinct from men, and (7) participants were 18 years of age or older. For the purposes of this review, we included only clinical trials as defined by the National Cancer Institute (2015) as, “a study in which participants are randomly assigned (by chance) to receive one of the several pharmacotherapies and/or behavioral interventions.”

For each eligible study, we abstracted information on the study population, intervention and comparison group, and main results. Because each study had different measures of alcohol use and slightly different combinations of treatments, we did not create a summary measure of risk; rather, we provided the results of each study. Drinking outcomes reported in the studies could be grouped into three general categories, including alcohol quantity (drinks per day, reduction in drinks/day, drinks per drinking day), frequency of drinking (days/month, percent drinking days (%), percent heavy drinking days (%), percent days abstinent (%)), and/or to time to relapse (time to any drinking, time to heavy drinking). Results were presented as significant differences if there was a statistically significant result (p<0.05); as trends if there was at least a 20% difference in outcomes, but the p-value was either not significant or not reported; and as “no difference” if the results were essentially the same or p-value was >0.5.

RESULTS

The screening of relevant titles yielded a total of 2,765 articles. After reviewing the full-text articles (n=37) an additional thirty studies were eliminated. The 7 studies included in this review presented drinking outcomes for women distinct from men. Five studies were double-blind RCTs, one study was a factorial design RCT, and another study conducted an exploratory analysis post-hoc analysis from a double-blind RCT. Participants were randomized to a group treated with naltrexone (either oral once daily or targeted (drinking days only) 50mg– 150mg or injectable naltrexone 380mg or 190mg, with or without a behavioral intervention or to a group receiving placebo with or without a behavioral intervention.

Six studies enrolled participants with alcohol dependence, diagnosed by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [Kranzler et al., 2009; Greenfield et al., 2010; O’Malley et al., 2007; Garbutt et al., 2009; Kiefer, Jahn & Wiedemann, 2005; Pettinati et al., 2008]. All of the studies except Pettinati et al. (2008) excluded persons who were dependent on substances other than alcohol or nicotine. The 7 studies included a total of 2,590 randomized participants, of whom 903 were women with a mean age range 39.2 to 49. In the four studies that reported race/ethnicity, the majority of women were Caucasian (n=576), followed by Hispanic (n=38), and then African American (n=37). Five studies reported the proportion of women who received naltrexone (daily or targeted) (n=271) or placebo (n=202) [Greenfield et al., 2010; O’Malley et al., 2007; Garbutt et al., 2009; Kiefer, Jahn & Wiedemann, 2005; Pettinati et al., 2008]. All of the studies reported the timing of intervention application, ranging from 8 weeks to 16 weeks. Furthermore, the 7 studies utilized variable participant recruitment methods: advertisements [Greenfield et al., 2010; O’Malley et al., 2007; Hernandez-Avila et al., 2006], clinicians referrals [Kranzler et al., 2009; Hernandez-Avila et al., 2006], alcohol treatment study sites [Greenfield et al., 2010; O’Malley et al., 2007; Kiefer, Jahn, & Wiedemann, 2005; Pettinati et al., 2008], public hospitals, private and Veteran Administration clinics, or tertiary care settings [Garbutt et al., 2009].

Study Summaries

Detailed information about each study is as follows (Table 1 includes study summary). Kranzler et al. (2009) conducted a 12-week factorial design study in the United States to determine the impact of targeted use of naltrexone to reduce heavy drinking. A total of 163 alcohol-dependent randomized participants (95 men and 68 women) received daily or targeted naltrexone (50mg/d) or daily or targeted placebo. The authors measured the drinking outcome drinks per day at multiple time points.

Table 1.

The main characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Methods | Participants | Recruitment | Interventions | Drinking Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kranzler et al., 2009 | RCT, factorial study design, 12-week study | Alcohol dependence (DSM-IV); 18–70 years old, women and men | Advertisements in local media, patient referrals by primary care physician or other clinician | NAL: naltrexone 50mg, (N= 83) PL: placebo tablet identical to naltrexone once daily: (N=80) BST: biweekly counseling sessions |

DPD: drinks per day |

| Greenfield et al., 2010 | RCT, double blind, 16-week study | Alcohol dependence (DSM-IV) 18 years and older, women and men | Advertisements and from clinical referrals at 11 academic sites | NAL: naltrexone 25mg, 50mg, or two 50mg once daily: (N= 49) PL: placebo tablet identical to naltrexone once daily: (N=50) MM: nine sessions of medical management delivered over (0,1,2,4,6,8,10,16) weeks |

PDA: percent days abstinent PHDD: percent heavy drinking days THDD: time to first heavy drinking day |

| O’Malley et al., 2007 | RCT, double blind, 12-week study | Alcohol dependence (DSM-IV); 18 to 55 years old, women only | Newspaper advertisements and from patients seeking treatment at the Substance Abuse Treatment Unit of the Connecticut Mental Health Center | NAL: naltrexone 50mg: (N= 53) PL: placebo tablet identical to naltrexone once daily: (N=50) CBCST: weekly group sessions |

PDA: percent days abstinent PHDD: percent heavy drinking days THDD: time to first heavy drinking day |

| Garbutt et al., 2009 | RCT, double blind 24-week study | Alcohol dependence (DSM-IV); 18 years or older, women and men | Public hospitals, private and Veteran Administration clinics, or tertiary care settings | NAL: naltrexone 380mg injectable, (N= 67), NAL: naltrexone 190mg injectable (N=68) PL: placebo (N=66) SST: 12 sessions |

HDD: number of heavy drinking days |

| Kiefer, Jahn and Wiedemann, 2005 | RCT, double blind 12-week study | Alcohol dependence (DSM-IV); 18–65 years old, women and men | Alcohol treatment study sites | NAL: naltrexone 50mg oral, (N= 9) PL: placebo tablet, 50 mg oral, (N=13) PT: biweekly group therapy |

TFD: Time to first drink THDD: Time to first heavy drinking day |

|

| |||||

| Hernandez-Avila et al., 2006 | RCT, double blind 8-week study | Heavy drinkers; 18–60 years old, women and men | Newspaper advertisements and referrals from area clinicians | NAL: naltrexone 50mg/daily, (N= 33) NAL: naltrexone, 50mg/targeted, (N= 42) PL: placebo tablet identical to naltrexone once daily 50mg: (N=39) PL: placebo, 50mg/targeted, (N= 36) BCST: counseling sessions |

DPD: drinks per day |

|

| |||||

| Pettinati et al., 2005 | RCT, double blind 12-week study | Alcohol dependence (DSM-IV); 18–65 years old, women and men | Alcohol treatment study sites | NAL: naltrexone 150mg, (N= 24) PL: placebo tablet identical to naltrexone once daily 150mg: (N=24) CBT: weekly counseling sessions |

AU: Alcohol use (measured in days) DD: drinking days (percent) DDD: drinks per drinking day HDD: Heavy drinking days |

NAL: Naltrexone; BST: Brief Skills Training; PL: Placebo; MM: Medical Management; CBST: Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills Therapy; AU: Alcohol use (measured in days); DD: Drinking days; DPD: Drinks per day; DDD: Drinks per drinking day; HDD: Heavy drinking days; PDA: Percent days abstinent; PHDD: Percent heavy drinking days; TFD: Time to first drink, THDD: Time to first heavy drinking day, SST: Standardized Supportive Therapy; PT: Psychotherapy; BCST: Brief Coping Skills Therapy; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Greenfield et al. (2010) conducted a secondary analysis of the COMBINE Study (a national, multisite 16-week double-blind study in the US) to assess gender differences in treatment outcomes. A total of 1226 alcohol-dependent randomized participants (848 men and 378 women) assigned to one of eight groups received medical management with active naltrexone (100mg/d) or placebo, active acamprosate (3g/day) or placebo, with or without a behavioral intervention (CBI). The study assessed drinking outcomes percent days abstinent, percent heavy drinking days, and time to first heavy drinking day.

O’Malley et al. (2007) conducted a double-blind, 12-week study in the United States to investigate the safety and efficacy of oral naltrexone 50mg in a sample of 103 alcohol-dependent randomized women who received naltrexone or placebo. The study assessed drinking outcomes percent days abstinent, percent heavy drinking days, and time to first heavy drinking day.

Garbutt et al. (2009) conducted a 24-week double-blind study in the United States to determine the efficacy and tolerability of a long-acting intramuscular formulation of naltrexone. A total of 624 alcohol-dependent randomized participants (423 men and 201 women) received long-acting injectable naltrexone (380mg or 190mg) or placebo and standardized supportive therapy. The study measured the drinking outcome number of heavy drinking days at multiple time points.

Kiefer, Jahn & Wiedemann (2005) conducted an exploratory analysis post-hoc from Kiefer et al., (2003) (a 12-week double-blind study in Germany) to compare and combine naltrexone and acamprosate in relapse prevention in alcoholism. A total of 160 alcohol-dependent randomized participants (118 men and 42 women) assigned to one of four groups received active naltrexone (50mg/d), acamprosate (1998mg/d), naltrexone plus acamprosate, or placebo. The authors measured drinking outcomes mean time to first drink and mean time to relapse.

Hernandez-Avila et al. (2006) conducted a secondary analysis of a study by Kranzler et al. (2003) (an 8-week double-blind study in the US) to examine the effects of daily naltrexone and targeted scheduled administration on a continuous outcome of drinks/day. A total of 150 heavy-drinking randomized participants (87 men and 63 women) assigned to one of four treatment groups received daily or targeted naltrexone (50mg/d) or daily or targeted placebo (50mg/day). The study measured the drinking outcome drinks per day at multiple time points.

Pettinati et al. (2008) conducted a 12-week double-blind study in the United States to determine the efficacy of a higher-than-normal daily dose of naltrexone among treatment-seeking participants with co-occurring cocaine and alcohol dependence. A total of 164 alcohol-dependent randomized participants (116 men and 48 women) received naltrexone (150mg/d) or placebo with cognitive behavioral therapy or medical management. The study measured drinking outcomes abstinence (yes/no), number of drinks per drinking day, the percentage of drinking days, and the percentage of heavy drinking days at multiple time points.

Study Outcomes

Overall, study outcomes focused on alcohol quantity (drinks per day, reduction in drinks/day, drinks per drinking day), frequency of drinking (days/month, percent drinking days (%), percent heavy drinking days (%), percent days abstinent (%)), and/or time to relapse (time to any drinking, time to heavy drinking).

Three studies reported findings related to drinking quantity. Kranzler et al. (2009) reported no difference in women’s drinking across the four study conditions (e.g. daily naltrexone, daily placebo, targeted naltrexone, and targeted placebo). However, a trend toward reduced alcohol consumption was observed among women at study week 12 in the daily naltrexone group compared to the daily placebo group (Naltrexone group: 2.6 drinks per day vs. placebo group: 3.5 drinks per day) (no p-value reported)[Kranzler et al., 2009]. Hernandez-Avila et al. (2005) reported no difference in mean drinks per day outcome among women at week 8 who received targeted naltrexone (2.75 drinks), targeted placebo group (2.5 drinks), daily naltrexone (2 drinks), or daily placebo (2 drinks) (no p-value reported). Pettinati et al. (2008) observed a trend toward reduced number of drinks per drinking day among women who received naltrexone (3.7 drinks (3.1)) versus placebo (6.4 drinks (6.7)) (no p-value reported).

Four studies considered the frequency of drinking as an outcome. Greenfield et al. (2010) observed a trend toward increased percentage of days abstinent among women who received naltrexone (78%) compared to placebo (71%) (p = 0.092); and a trend toward decreased percentage of heavy drinking days was observed among women receiving naltrexone (Naltrexone 14% of days vs. Placebo: 20.5% of days)) (no p-value reported)[Greenfield et al., 2010]. O’Malley et al. (2007) reported no difference in percent days abstinent (p = >.30) or percent heavy drinking days (p = >.30) among women who received naltrexone or placebo (actual results not provided). Pettinati et al. (2008) found a trend toward an increase in the percentage of any drinking days among women who received naltrexone (14.8% (16.6)) vs. placebo (9.8%(12.0)); but no difference in percentage of heavy drinking days among women (Naltrexone group: 6.9% (10.6) vs. Placebo group: 7.8% (12.2)) (no p-value reported). Garbutt et al. (2005) observed a trend toward greater percent drinking days among women who received 380mg injectable naltrexone vs. placebo, (HR, 1.23 (0.85–1.78), p = 0.28) or 190mg injectable naltrexone vs. placebo (HR, 1.07 (0.73–1.58), p = 0.72).

Three studies reported findings on the time to first drink outcome. Kiefer, Jahn, & Wiedemann (2005) observed a significantly longer time to first drink among women who received oral naltrexone (68.9 ± 8.7 days) vs. placebo (19.2 ± 6.1 days) (p < 0.001); and a significant increase in time to first heavy drinking day among women who received naltrexone (77.0 ± 8.0 days) vs. placebo (32.2 ± 8.0 days) (p < 0.05). Greenfield et al. (2010) observed a trend in longer time to relapse to first heavy drinking day (number of days in which 50% of the sample returned to drinking) among women who received naltrexone (42 days) vs. placebo (18 days)(p-value not reported). O’Malley et al. (2007) found no significant difference in time to return to drinking among women who received naltrexone (30 days) vs. placebo (40 days) (p = 0.88)

DISCUSSION

Our review systematically reviewed and summarized the evidence regarding the impact of naltrexone compared to placebo for attenuating alcohol consumption. To date, this is the first systematic literature review that focuses solely on women with an AUD. Our review identified seven studies conducted between 1990–2016 that met the a priori inclusion criteria. Two of the three studies examining the quantity of drinks per day observed trends toward reduction in drinking quantity among women who received naltrexone vs. placebo. The 4 studies examining the frequency of drinking had mixed results, with one study showing a trend that favored naltrexone, two showing a trend that favored placebo, and one that showed no difference. Two of the three studies examining time to relapse observed trends that tended to favor naltrexone for time to any drinking and time to heavy drinking among women who received naltrexone vs. placebo. Taken together, the results suggest that naltrexone may lead to modest reductions in quantity of drinking and time to relapse, but not on the frequency of drinking in women. However, among 7 studies, only 1 reported a statistically significant improvement in drinking outcomes among women who received naltrexone vs. placebo.

Due to a limited amount of research examining gender difference regarding naltrexone’s effectiveness coupled with the variability in intervention prescription dosage/duration, it is not possible to identify the optimal approach for use of naltrexone to treat alcohol use disorders in women. Unlike previously conducted systematic reviews [Srisurapanont & Jarusuraisin, 2005; Maisel et al., 2012], our review focused on women with an AUD or other evidence of serious drinking. Thus, this review was imperative given that many studies have not explored gender differences in the efficacy of naltrexone for women distinct from men. Six studies reported results for both men and three of these observed trends that indicated the effect of naltrexone to reduce drinking was stronger in men than in women [Kranzler et al., 2009; Garbutt et al., 2009; Pettinati et al., 2008].

We note several potential limitations as context for interpreting our findings. Four studies included fewer than 100 women and were relatively underpowered to detect significant changes in drinking over time. [Kranzler et al., 2009; Kiefer, Jahn & Wiedemann, 2005; Hernandez-Avila et al., 2006; Pettinati et al., 2008]. Due to the low representation of minority women in the 7 studies, results may not be generalizable to women of other ethnic/racial groups. Next, the intervention components varied across all of the studies with some women receiving more counseling interventions than others. Additionally, the measurement of alcohol consumption is limited to self-report, and our review only included one study using depot (injectable) naltrexone [Garbutt et al., 2005]. Most notably, the review lacked studies with common intervention strategies or outcome measures to justify doing a statistical summary of effect using meta-analysis techniques as done in other reviews.

In summary, the limited existing evidence suggests that naltrexone may have a very modest effect on drinking quantity and time to relapse, but not on overall frequency of drinking among women. Over time, better interventions are needed that can demonstrate a greater magnitude of effect. While the growing body of evidence suggests a variety of pharmacotherapy and behavioral intervention approaches to treat alcohol use disorders (AUD), the impact of naltrexone on combatting AUD in women is understudied. Future research should incorporate sophisticated study designs that examine gender differences and treatment effectiveness among those diagnosed with an AUD and present data separately for men and women. This may lead to the development of better treatment options for women or the ability to identify the subset of women who might benefit most from naltrexone.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant 3U01AA020797-04S1 and U2AA4022002 from the NIAAA.

References

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;295(17):2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmen B, Angeles M, Ana M, María AJ. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction. 2004;99(7):811–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer.gov. [Accessed October 19, 2015];Definition of randomized clinical trial - NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms - National Cancer Institute. 2016 [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms?cdrid=45858.

- CDC.gov. [Accessed May 25, 2016];CDC - Fact Sheets-Alcohol Use And Health - Alcohol. 2016a [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm.

- CDC.gov. [Accessed May 25, 2016];CDC - Alcohol and Public Health Home Page - Alcohol. 2016b [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Alcohol/

- CDC.gov. [Accessed May 25, 2016];CDC - Fact Sheets-Excessive Alcohol Use and Risks to Women’s Health - Alcohol. 2016c [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/womens-health.htm.

- Diehl A, Croissant B, Batra A, Mundle G, Nakovics H, Mann K. Alcoholism in women: is it different in onset and outcome compared to men? European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2007;257(6):344–351. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0737-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C. Influence of the endogenous opioid system on high alcohol consumption and genetic predisposition to alcoholism. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience: JPN. 2001;26(4):304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, Loewy JW, Ehrich EW Vivitrex Study Group. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2005;293(13):1617–1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Pettinati HM, O’Malley S, Randall PK, Randall CL. Gender differences in alcohol treatment: an analysis of outcome from the COMBINE study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(10):1803–1812. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Avila CA, Song C, Kuo L, Tennen H, Armeli S, Kranzler HR. Targeted versus daily naltrexone: secondary analysis of effects on average daily drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(5):860–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, Bobashev G, Thomas K, Wines R, Kim MM, Shanahan E, Gass CE, Rowe CJ, Garbutt JC. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2014;311(18):1889–1900. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F, Jahn H, Wiedemann K. A neuroendocrinological hypothesis on gender effects of naltrexone in relapse prevention treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38(04):184–186. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Tennen H, Armeli S, Chan G, Covault J, Arias A, Oncken C. Targeted naltrexone for problem drinkers. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2009;29(4):350. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181ac5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, Kirk GF, Rosenheck RA. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(24):1734–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, King AC, Farag NH, Sorocco KH, Cohoon AJ, Vincent AS. Naltrexone effects on cortisol secretion in women and men in relation to a family history of alcoholism: studies from the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns Project. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(12):1922–1928. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K, Ackermann K, Croissant B, Mundle G, Nakovics H, Diehl A. Neuroimaging of gender differences in alcohol dependence: are women more vulnerable? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(5):896–901. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164376.69978.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K, Batra A, Günthner A, Schroth G. Do women develop alcoholic brain damage more readily than men? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16(6):1052–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Jama. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):212–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependency, Inc. [Accessed November 30, 2016];Alcoholism, Drug Dependence and Women. 2015 [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.ncadd.org/about-addiction/addiction-update/alcoholism-drug-dependence-and-women.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) [Accessed October 10, 2015];Alcohol Facts and Statistics | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) 2016 [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-facts-and-statistics.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) [Accessed October 10, 2015];Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM-IV and DSM-5. 2016 [ONLINE] Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/dsmfactsheet/dsmfact.pdf.

- O’Malley SS, Sinha R, Grilo CM, Capone C, Farren CK, McKee SA, Rounsaville BJ, Wu R. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral coping skills therapy for the treatment of alcohol drinking and eating disorder features in alcohol-dependent women: a randomized controlled trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(4):625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Suh JJ, Dackis CA, Oslin DW, O’Brien CP. Gender differences with high-dose naltrexone in patients with co-occurring cocaine and alcohol dependence. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2008;34(4):378–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce G, Sanchez-Garcia J, Rubio G, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Jimenez-Arriero MA, Palomo T. Efficacy of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence disorder in women. Actas espanolas de psiquiatria. 2004;33(1):13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Publications | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism | Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM–IV and DSM–5. [Accessed 25 May 2016];Publications | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism | Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM–IV and DSM–5. 2016 [ONLINE] Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/dsmfactsheet/dsmfact.htm.

- Roozen HG, de Waart R, van den Brink W. Efficacy and tolerability of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: oral versus injectable delivery. European addiction research. 2007;13(4):201–206. doi: 10.1159/000104882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Substance Dependence or Abuse in the Past Year among Persons Aged 18 or Older by Demographic Characteristics. 2012 Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2012/NSDUH-DetTabs2012/HTML/NSDUH-DetTabsSect5peTabs1to56-2012.htm#Tab5.8A.

- Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;8(02):267–280. doi: 10.1017/S1461145704004997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeton C, Whelan G. Naltrexone, a relapse prevention maintenance treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2001;36(6):544–552. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, et al. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11:E109. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey JW, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Gwaltney CJ, Miranda R, McGeary JE, MacKillop J, Swift RM, Abrams DB, Shiffman S, Paty JA. Moderators of Naltrexone’s Effects on Drinking, Urge, and Alcohol Effects in Non-Treatment-Seeking Heavy Drinkers in the Natural Environment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(1):58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]