Abstract

Compared to normal cells, cancer cells have a unique metabolism by performing lactic acid fermentation in the presence of oxygen, also known as the Warburg effect. Researchers have proposed several hypotheses to elucidate the phenomenon, but the mechanism is still an enigma. In this review, we discuss three typical models, such as “damaged mitochondria”, “adaptation to hypoxia”, and “cell proliferation requirement”, as well as contributions from mass spectrometry analysis toward our understanding of the Warburg effect. Mass spectrometry analysis supports the “adaptation to hypoxia” model that cancer cells are using quasi-anaerobic fermentation to reduce oxygen consumption in vivo. We further propose that hypoxia is an early event and it plays a crucial role in carcinoma initiation and development.

Keywords: Cancer metabolism, Warburg effect, mass spectrometry, review

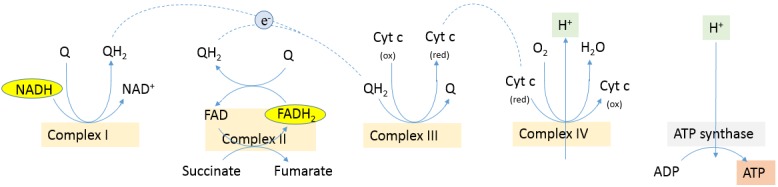

Living organisms are able to carry-out a highly integrated network of chemical reactions, known as metabolism, in order to extract energy and reducing power from their environment and synthesize the building blocks of macromolecules (1). In mammalian cells, the first step in the degradation of glucose is glycolysis that is an oxygen-independent metabolic pathway. Pyruvate molecules produced by glycolysis are actively transported across the inner mitochondrial membrane, and into the matrix. Pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA by oxidative decarboxylation catalyzed by the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex. Then, acetyl-CoA is fed into the Krebs (also known as tricarboxylic acid, TCA) cycle. Carbon dioxide and NADH are produced both by the PDH-catalyzed oxidative decarboxylation and the TCA cycle, and the latter also produces FADH2. The NADH and FADH2 formed in glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation and the Krebs cycle are energy-rich molecules because each contains a pair of electrons that have a high transfer potential. When these electrons are donated to molecular oxygen through a series of electron carriers in mitochondria, a large amount of free energy is liberated to generate ATP as shown in Figure 1. Fermentation is less efficient at using the energy from glucose: only 2 ATP are produced per glucose, compared to the 38 ATP per glucose produced by aerobic respiration.

Figure 1. Oxidative phosphorylation in mammalian cell. Electrons are transferred from NADH and FADH2 to oxygen in redox reactions. These redox reactions are carried out by a series of protein complexes (NADH dehydrogenase or complex I, succinate dehydrogenase or complex II, cytochrome c reductase or complex III, cytochrome c oxidase or complex IV). The energy released by electrons flowing through the electron transport chain is used to transport protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This pH gradient generates an electrical potential energy across the membrane. When protons flow back across the membrane through ATP synthase, the energy is stored in ATP (1). Cytochrome c oxidase mediates the final reaction in the electron transport chain and transfers electrons to oxygen, while pumping protons across the membrane (2, 3).

It is well-known that cancer cells have a unique metabolism compared to normal cells. In the 1920s, using slices of living tissues, Otto Warburg studied the energy metabolism of a tumor and first reported that cancer cells produced large amounts of lactate even in aerobic condition (4). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1931 for his "discovery of the nature and mode of action of the respiratory enzyme." In oncology, the Warburg effect is the observation that most cancer cells predominantly produce energy by a high rate of glycolysis followed by lactic acid fermentation in the cytosol, rather than by a comparatively low rate of glycolysis followed by oxidation of pyruvate in mitochondria as in most normal cells (5-7). Investigators have proposed several hypotheses to elucidate the mechanism, but a unanimous agreement has not been reached (8,9). Herein, we attempt to discuss three typical models and the contributions of mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomic analysis.

Model 1: Damaged Mitochondria

In the 1920s, it was well-known that eukaryotic cells use mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to obtain energy in aerobic condition and perform fermentation in anaerobic condition. When Otto Warburg observed that cancer cells produced lactic acid in vitro with ample oxygen, it was quite logical for him to deduce that there must be something wrong in the cancer cell’s mitochondria, disallowing the cell to perform oxidative phosphorylation in the presence of oxygen. Otto Warburg presumed that the in vivo microenvironment (nutrient, oxygen) of the cancer cell is the same as that of the normal cell, and he believed that the phenomenon is also displayed in vivo. He further developed a hypothesis that cancer should be interpreted as a mitochondrial dysfunction (4). However, this hypothesis is opposed by Sidney Weinhouse who reported that tumors and non-neoplastic tissues show no difference in their ability to convert glucose and fatty acids to carbon dioxide, a process that requires respiration and functional mitochondria. Weinhouse postulated that the increased glycolysis noted in all tumors was not the cause of the malignancy but a result of alterations in genetic function that affect specific genes that regulate the expression of the enzymes and other factors that control a complex metabolic pathway (10,11).

Today, hypotheses similar to Warburg’s “Damaged mitochondria” model are still popular in the cancer research field (12). For instance, a number of mutations among the TCA cycle enzymes, such as succinate dehydrogenase, fumarate hydratase, and isocitrate dehydrogenase, have been discovered and their association with some tumor types has been established (13,14). Additionally, some researchers support a hypothesis that cancer cells have increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to a decline of ROS-scavenging enzyme superoxide dismutase in mitochondria. These researchers believe that the increase of ROS in cancer cells plays an important role in cancer initiation and progression (15-21).

Model 2: Adaptation to Hypoxia

Human cancers have been described for more than 2,000 years. The name “cancer”, referring to “crab” in the Greek language, comes from the appearance of the cut surface of a solid malignant tumor, with the veins stretched on all sides, similar to the position of a crab’s legs (22). At first glance, tumors have blood vessels and are accessible to oxygen. However, analysis from Less et al. shows that solid tumor vascular architecture, while exhibiting several features that are similar to those observed in normal tissues, has others that are not commonly seen in normal tissues. These features of the tumor microcirculation may lead to heterogeneous local hematocrits, oxygen tensions, and drug concentrations, thus reducing the efficacy of present day cancer therapies (23). Contrary to Otto Warburg’s presumption that oxygen deficiency is out of the question for cancer cells in vivo, some investigators believe that oxygen is a serious limiting factor for cancer cells in vivo. In the past several decades, researchers observed that regions within solid tumors experience mild to severe oxygen deprivation, due to aberrant vascular function. These hypoxic regions are associated with altered cellular metabolism, as well as increased resistance to radiation and chemotherapy (7,24).

Notably, Gatenby and Gillies proposed that the Warburg effect is an adaptation to intermittent hypoxia in pre-malignant lesions: “the pre-malignant lesions, provided their basement membranes remain intact, will inevitably develop hypoxic regions near the oxygen diffusion limit, as persistent proliferation leads to a thickening of the epithelial layer, pushing cells ever more distant from their blood supply, which remains on the other side of the basement membrane.” They explained that cells derived from tumors typically maintain their metabolic phenotypes in culture under normoxic conditions due to stable genetic or epigenetic changes (25,26). Basically, this model supports an idea that the cancer cells are performing anaerobic fermentation due to hypoxia and will not display the Warburg effect (aerobic fermentation) in vivo.

Model 3: Cell Proliferation Requirement

In the year 2008, Christofk et al. reported that tumor cells express exclusively the embryonic M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase (PKM2) and switching pyruvate kinase expression to the M1 form (PKM1) leads to reversal of the Warburg effect. The authors concluded that the PKM2 expression is necessary for aerobic glycolysis and that this metabolic phenotype provides a selective growth advantage for tumor cells in vivo (27). The authors further suggested that selective targeting of PKM2 by small-molecule inhibitors is feasible for cancer therapy (28). This report attracted much attention in the research field of cancer, and some researchers performed follow-up studies to understand the PKM2 activity regulation in tumor cells (29-39). However, the authors’ statement that “tumor cells express exclusively PKM2” is not consistent with previous publications that PKM2 is expressed in lung tissues as well as all cells with high rates of nucleic acid synthesis (40,41). The authors’ statement that “there is a switch of PKM1 to PKM2 during development of cancer” is also challenged by a quantitative MS analysis that PKM2 is the prominent isoform in several analyzed cancer samples and matched control tissues (42). Noticeably, the knowledge that PMK2 is indeed expressed in normal tissue is now accepted in the cancer research community after these arguments (43).

Vander Heiden et al. further developed the “Cell proliferation requirement” model and disagreed with the above “Adaptation to hypoxia” model that tumor hypoxia selects for cells dependent on anaerobic metabolism (44). The authors argued that: “cancer cells appear to use glycolytic metabolism before exposure to hypoxic conditions. For example, leukemic cells are highly glycolytic, yet these cells reside within the bloodstream at higher oxygen tensions than cells in most normal tissues. Similarly, lung tumors arising in the airways exhibit aerobic glycolysis even though these tumor cells are exposed to oxygen during tumorigenesis.” The authors believed that hypoxia is a late-occurring event that may not be a major contributor in the switch from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis by cancer cells. The authors concluded that lactate fermentation is required for normal proliferative tissue or tumor (5% pyruvate enters into TCA, 85% pyruvate converts to lactate), suggesting that oxidative phosphorylation and cell proliferation are largely mutually exclusive. This conclusion is based on a statement that “many unicellular organisms proliferate using fermentation.” However, using this statement as an evidence to support the authors’ “Cell proliferation requirement” model is questionable. For example, yeast, a centrally important unicellular model organism in modern cell biology research and one of the most thoroughly researched eukaryotic microorganisms, produces ethanol by fermentation under low-oxygen conditions. In 1857, French microbiologist Louis Pasteur showed that by bubbling oxygen into the yeast broth, cell growth could be increased, but fermentation was inhibited – an observation later called the Pasteur effect (45). Surely, fermentation is not a necessity for yeast proliferation and yeast does not preferentially ferment glucose when oxygen is abundant. Anyway, this model is welcomed among some researchers who are interested in targeting of cancer metabolism (46,47).

Contribution by Mass Spectrometry Analysis

MS is used routinely for large-scale protein identification and global profiling of post-translational modifications (PTMs) from complex biological mixtures. Remarkably, the MS analyses have identified a large number of dysregulated metabolic enzymes including PKM2 in cancer cells. Particularly, the MS analysis showed that L-lactate dehydrogenase B (LDH-B) is up-regulated in pancreatic cancer cells, indicating that LDH-B is in great need for lactic acid fermentation (Table I). On the contrary, mitochondrial proteins are down-regulated in cancer cells, resulting from either decreased expression of proteins in each individual mitochondrion or a lessened number of mitochondria in each cell (48-50). The down-regulation of mitochondrial proteins was also observed by Pan et al. in one MS analysis of mouse hepatoma cell. The authors further confirmed that the number of mitochondria in the cancer cell is reduced by fluorescent staining of mitochondria (51). This observation implicates that, even though cancer cells harness a lower number of mitochondria, these mitochondria are sufficient for macromolecules synthesis and energy production requirement. According to adaptation theory, cells will express proteins when needed, and reduce proteins when not needed. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that cancer cells need less mitochondria because less oxygen is consumed. All things considered, the MS analysis of cancer metabolism largely supports a revised “Adaptation to hypoxia” model that cancer cells are using quasi-anaerobic fermentation to reduce oxygen consumption in vivo (52). In this model, each mitochondrion in a cancer cell is still active, consistent with the observation by Weinhouse; however, compared to normal cells, cancer cells have lessened oxidative phosphorylation capacity at cellular level. Additionally, the proteomic data suggest that the Warburg effect is a consequence of an adaptation to low-oxygen environments within tumors, and the tumor-derived cell lines can maintain their metabolic phenotype in culture under regular condition with ample oxygen, due to irreversible gene mutations in the cells, as proposed by Weinhouse.

Table I. The important MS studies related to the Warburg effect.

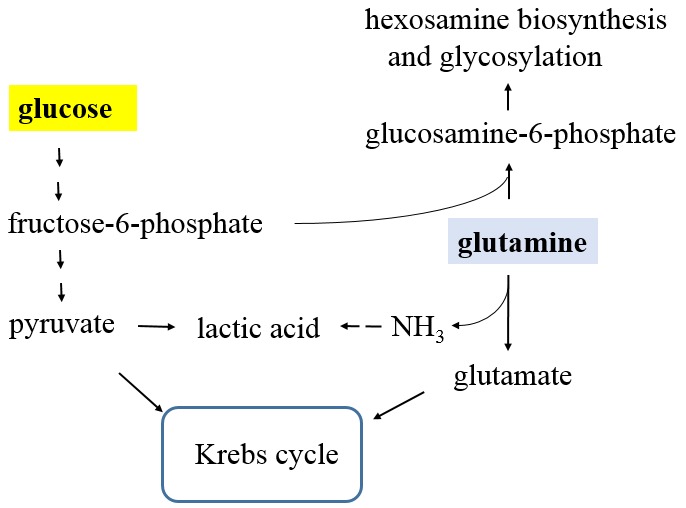

Next, compared with normal cells, tumor cells produce increased amounts of protons (H+) owing to lactic acid fermentation. The role of the proton transporter in the pH homeostasis in cancer cells has been discussed previously (53). Notably, the MS analysis confirmed that glutaminase is up-regulated in cancer cells (49). Since glutamine can be hydrolyzed to glutamate and ammonia by glutaminase, we propose that the reaction of ammonia with lactic acid can play a part in the pH balance in cancer cells as shown in Figure 2. Since many cultured cancer cells exhibit increased glutamine consumption (54), this proposal may help to explain the glutamine addiction by cancer cells.

Figure 2. The link of glycolysis and glutaminolysis. Pyruvate and glutamate, products from glycolysis and glutaminolysis, are substrates for Krebs cycle. Separately, glutamine and fructose-6-phosphate (product from glycolysis) are used for hexosamine biosynthesis and glycosylation, catalyzed by glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate transaminase. Additionally, glutamine can be hydrolyzed to glutamate and ammonia (NH3) by glutaminase. The resulted ammonia can react with lactic acid to form ammonium lactate to help the pH balance in cancer cells.

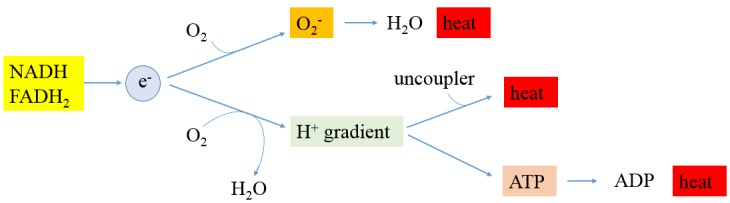

Moreover, the MS analysis showed that enzymes involved in oxidative stress in cancer cells are down-regulated, indicating that cancer cells have lower oxidative stress, and cancer cells adaptively lessened the expression of these enzymes (49). This conclusion does not support the current prevailing ROS theory that cancer cells have higher ROS. According to the cancer ROS theory, antioxidants can be used by healthy people and cancer patients as a strategy to fight cancer; however, some clinical trials with antioxidants show that antioxidants actually increase cancer risks (55,56). Here, we suggest that ROS production is an important heat generation mechanism in normal cells as shown in Figure 3. In mammalian cells, oxygen is the final electron acceptor, and the consumption of oxygen is proportional to heat production. Therefore, compared to normal cells, hypoxic cancer cells consume less oxygen and will generate less heat. Indeed, using a thermographic imaging technique, Song et al. observed that the tumors are cooler than the surrounding tissue (59).

Figure 3. Heat production in mammalian cells. About 2,880 kJ mol–1 of energy is released when burning glucose in air (C6H12O6 + 6O2 → 6CO2 + 6H2O). The same amount of energy will be released by aerobic respiration in mammalian cells; however, the chemical energy is first stored in synthesized ATP by a series of biochemical reactions including glycolysis, Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation, and the energy stored in ATP can then be released in a controlled way to drive processes requiring energy such as biosynthesis and transportation of molecules. Surprisingly, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation as shown in Figure 1 is not perfectly coupled to ATP synthesis. Proton-leak catalyzed by uncoupling proteins in adipocytes accounts for a significant part of the resting metabolic rate (57). Separately, although the last destination for an electron along the electron transport chain is an oxygen molecule to form water catalyzed by cytochrome c oxidase in normal conditions, a certain percentageof electrons can be leaked before this reaction takes place and oxygen is prematurely and incompletely reduced to superoxide radical (O2 + e– →O2–) (58). In compliance with the relationship of chemical reaction rate and concentration, it is expected that less superoxide radical can be formed in hypoxia condition. Remarkably, it is well-established that mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide (Mn3+-SOD + O2− → Mn2+-SOD + O2, Mn2+-SOD + O2− + 2 H+ → Mn3+-SOD + H2O2). Catalase, which is concentrated in peroxisomes located next to mitochondria, reacts with the hydrogen peroxide to catalyze the formation of water and oxygen (2 H2O2 → 2 H2O + O2). Consequently, the combined reaction catalyzed by superoxide dismutase and catalase is 4 O2− + 4 H+ → 2 H2O + 3 O2, and energy stored in superoxide radical is released as heat.

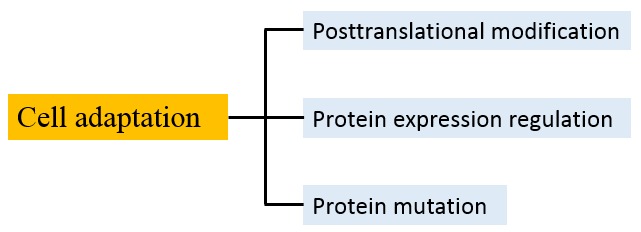

By and large, cancer is a genetic disease. Many important genes responsible for the genesis of various cancers have been discovered, their mutations precisely identified, and the pathways through which they act characterized (60). Recently, Tomasetti and Vogelstein et al. reported that lifetime cancer risk for particular tissues is mostly determined by the total number of stem cell divisions within the tissue, whereby most cancers arise due to "bad luck" – random mutations arising during DNA replication in normal, noncancerous stem cells (61). However, some researchers disagree with this conclusion. They argue that some mutations are initiated by chemical or viral exposures, and others occur without a known cause (62,63). Certainly, there are many types of cancer, and it is hard to use one model to describe the origin of cancer. Here, we postulate that hypoxia can be developed from long-term inflammation or carcinogen-induced local capillary circulation deficiency, and hypoxia promotes gene mutations in epithelial cells and selects the cell that is adapted to a low-oxygen environment, resulting in carcinoma initiation and development. This hypothesis is based on our characterization of cellular adaptation mechanism as shown in Figure 4. Noticeably, Zhang et al. recently proposed a driver model for the initiation and early development of solid cancers associated with inflammation-induced chronic hypoxia and ROS accumulation (69). We agree that hypoxia plays a crucial role in carcinoma initiation and development; however, we believe that ROS accumulation is insignificant in hypoxic cells and mutation is likely attributed to an unrevealed mechanism.

Figure 4. Mechanisms of cellular adaptation. Living organisms face a succession of environmental challenges as they grow and develop. In response to the imposed conditions, organisms are equipped with adaptive traits that are maintained and evolved by means of natural selection. Adaptation can be achieved by three typical mechanisms at the molecular and cellular level. First, reversible post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and methylation, are involved in rapid adaption of cellular exposure to stimulus. At physiological pH, the side chains of Ser/Thr/Tyr are not charged, the side chain of lysine is cationic, and the side chains of Asp/Glu are negatively charged. Consequently, phosphorylation of Ser/Thr/Tyr will introduce negative charge to these amino acid residues; N-acetylation of lysine side chain will quench the positive charge; methylation on carboxylate side chain will cover up a negative charge and add hydrophobicity. PTMmediated adaptation can be quickly achieved by affecting of protein’s catalytic activity, localization in the cell, stability, and the ability to form complex with other molecules. Second, by gene regulation, cells can express protein when needed. For example, Jacob and Monod et al. discovered the lac operon regulation system in the genome of E. coli in which some enzymes involved in lactose metabolism are expressed in the presence of lactose and absence of glucose (64). Since this mechanism requires de novo mRNA and protein synthesis, it is a slower response compared to PTMs. Third, in extreme conditions, cells are prepared to resort to gene mutation for survival if the above two mechanisms fail. The mutant protein gains a new catalytic activity that helps the cell to overcome harsh conditions. Although the intrinsic mutation rate is quite low (65), the rate can be increased under selection pressure such as hypoxia. This mechanism is supported by reports that sub-lethal antibiotic treatment can increase bacteria’s mutation rate and drug resistance (66-68).

Perspectives

Cancer cells are cells that grow and divide at an unregulated, quickened pace, due to damaged or changed genetic material DNA. In the year 2000, Hanahan and Weinberg et al. published a well-cited article “The hallmarks of Cancer” to describe the characteristics of a cancer cell. The hallmarks of cancer comprise six biological capabilities acquired during the multistep development of human tumors. They include sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, and activating invasion and metastasis (70). In the year 2011, based on the recent research progress, Hanahan and Weinberg et al. published another article and added two more hallmarks of cancer without mention of the oxidative stress theory: reprogramming of energy metabolism, and evading immune destruction (71). Apparently, our understanding of cancer is still evolving and the importance of metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells is being increasingly recognized.

Cancer has been studied for many years, and scientists are still confronting the endless complexity of this disease (72). To date, the mechanism of the Warburg effect is still controversial, and discussions will continue among cancer researchers. As a powerful proteomic tool, MS technique recently has been applied to study cancer proteomes, and a large number of differentially expressed proteins including metabolic enzymes were revealed in cancer cells (73-76). There is no doubt that the continuous study of cancer metabolism by various tools including MS will benefit our understanding of the Warburg effect.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank the support from the College of Science in George Mason University.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stryer L. Biochemistry. W. H. Freeman and Company. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshikawa S, Muramoto K, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Aoyama H, Tsukihara T, Shimokata K, Katayama Y, Shimada H. Proton pumping mechanism of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1110–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brzezinski P, Gennis RB. Cytochrome c oxidase: exciting progress and remaining mysteries. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:521–531. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9181-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otto AM. Warburg effect(s)-a biographical sketch of Otto Warburg and his impacts on tumor metabolism. Cancer Metab. 2016;4:5. doi: 10.1186/s40170-016-0145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns RA. Drivers of the Warburg phenotype. Cancer J. 2015;21:56–61. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira LM. Cancer metabolism: the Warburg effect today. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010;89:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potter M, Newport E, Morten KJ. The Warburg effect: 80 years on. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:1499–1505. doi: 10.1042/BST20160094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinhouse S. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:267–269. doi: 10.1126/science.124.3215.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinhouse S. The Warburg hypothesis fifty years later. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1976;87:115–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00284370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boland ML, Chourasia AH, Macleod KF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer. Front Oncol. 2013;3:292. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desideri E, Vegliante R, Ciriolo MR. Mitochondrial dysfunctions in cancer: genetic defects and oncogenic signaling impinging on TCA cycle activity. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lokody I. Anticancer drugs: IDH2 drives cancer in vivo. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:826–827. doi: 10.1038/nrd4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohsawa S, Sato Y, Enomoto M, Nakamura M, Betsumiya A, Igaki T. Mitochondrial defect drives non-autonomous tumour progression through Hippo signalling in Drosophila. Nature. 2012;490:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabharwal SS, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles’ heel. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nrc3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan LB, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and cancer. Cancer Metab. 2014;2:17. doi: 10.1186/2049-3002-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa A, Scholer-Dahirel A, Mechta-Grigoriou F. The role of reactive oxygen species and metabolism on cancer cells and their microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;25:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Useros J, Li W, Cabeza-Morales M, Garcia-Foncillas J. Oxidative stress: a new target for pancreatic cancer prognosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2017;6:pii E29. doi: 10.3390/jcm6030029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galadari S, Rahman A, Pallichankandy S, Thayyullathil F. Reactive oxygen species and cancer paradox: to promote or to suppress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;104:144–164. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hajdu SI. A note from history: landmarks in history of cancer, part 1. Cancer. 2011;117:1097–1102. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Less JR, Skalak TC, Sevick EM, Jain RK. Microvascular architecture in a mammary carcinoma: branching patterns and vessel dimensions. Cancer Res. 1991;51:265–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertout JA, Patel SA, Simon MC. The impact of O2 availability on human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:967–975. doi: 10.1038/nrc2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891–899. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillies RJ, Gatenby RA. Metabolism and its sequelae in cancer evolution and therapy. Cancer J. 2015;21:88–96. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL, Cantley LC. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 2008;452:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vander Heiden MG, Christofk HR, Schuman E, Subtelny AO, Sharfi H, Harlow EE, Xian J, Cantley LC. Identification of small molecule inhibitors of pyruvate kinase M2. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1118–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Wu N, Asara JM, Cantley LC. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a phosphotyrosinebinding protein. Nature. 2008;452:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature06667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hitosugi T, Kang S, Vander Heiden MG, Chung TW, Elf S, Lythgoe K, Dong S, Lonial S, Wang X, Chen GZ, Xie J, Gu TL, Polakiewicz RD, Roesel JL, Boggon TJ, Khuri FR, Gilliland DG, Cantley LC, Kaufman J, Chen J. Tyrosine phosphorylation inhibits PKM2 to promote the Warburg effect and tumor growth. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra73. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anastasiou D, Poulogiannis G, Asara JM, Boxer MB, Jiang JK, Shen M, Bellinger G, Sasaki AT, Locasale JW, Auld DS, Thomas CJ, Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC. Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 by reactive oxygen species contributes to cellular antioxidant responses. Science. 2011;334:1278–1283. doi: 10.1126/science.1211485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lv L, Li D, Zhao D, Lin R, Chu Y, Zhang H, Zha Z, Liu Y, Li Z, Xu Y, Wang G, Huang Y, Xiong Y, Guan KL, Lei QY. Acetylation targets the M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase for degradation through chaperone-mediated autophagy and promotes tumor growth. Mol Cell. 2011;42:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo W, Hu H, Chang R, Zhong J, Knabel M, O’Meally R, Cole RN, Pandey A, Semenza GL. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a PHD3-stimulated coactivator for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;145:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaneton B, Hillmann P, Zheng L, Martin AC, Maddocks OD, Chokkathukalam A, Coyle JE, Jankevics A, Holding FP, Vousden KH, Frezza C, O’Reilly M, Gottlieb E. Serine is a natural ligand and allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase M2. Nature. 2012;491:458–462. doi: 10.1038/nature11540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang W, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Ji H, Chen X, Guo F, Lyssiotis CA, Aldape K, Cantley LC, Lu Z. ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1295–1304. doi: 10.1038/ncb2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Israelsen WJ, Dayton TL, Davidson SM, Fiske BP, Hosios AM, Bellinger G, Li J, Yu Y, Sasaki M, Horner JW, Burga LN, Xie J, Jurczak MJ, DePinho RA, Clish CB, Jacks T, Kibbey RG, Wulf GM, Di Vizio D, Mills GB, Cantley LC, Vander Heiden MG. PKM2 isoform-specific deletion reveals a differential requirement for pyruvate kinase in tumor cells. Cell. 2013;155:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iqbal MA, Gupta V, Gopinath P, Mazurek S, Bamezai RN. Pyruvate kinase M2 and cancer: an updated assessment. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2685–2692. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu VM, Van der Heiden MG. The role of pyruvate kinase M2 in cancer metabolism. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:781–783. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dayton TL, Jacks T, Van der Heiden MG. PKM2, cancer metabolism, and the road ahead. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1721–1730. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazurek S, Boschek CB, Hugo F, Eigenbrodt E. Pyruvate kinase type M2 and its role in tumor growth and spreading. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazurek S. Pyruvate kinase type M2: a key regulator of the metabolic budget system in tumor cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bluemlein K, Grüning NM, Feichtinger RG, Lehrach H, Kofler B, Ralser M. No evidence for a shift in pyruvate kinase PKM1 to PKM2 expression during tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2011;2:393–400. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Israelsen WJ, Van der Heiden MG. Pyruvate kinase: Function, regulation and role in cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;43:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van der Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krebs HA. The Pasteur effect and the relations between respiration and fermentation. Essays Biochem. 1972;8:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee N, Kim D. Cancer metabolism: fueling more than just growth. Mol Cells. 2016;39:847–854. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith LK, Rao AD, McArthur GA. Targeting metabolic reprogramming as a potential therapeutic strategy in melanoma. Pharmacol Res. 2016;107:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou W, Capello M, Fredolini C, Piemonti L, Liotta LA, Novelli F, Petricoin EF. Proteomic analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells reveals metabolic alterations. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1944–1152. doi: 10.1021/pr101179t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou W, Capello M, Fredolini C, Racanicchi L, Piemonti L, Liotta LA, Novelli F, Petricoin EF. Proteomic analysis reveals Warburg effect and anomalous metabolism of glutamine in pancreatic cancer cells. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:554–563. doi: 10.1021/pr2009274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou W, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF. Cancer metabolism: what we can learn from proteomic analysis by mass spectrometry. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2012;9:373–381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan C, Kumar C, Bohl S, Klingmueller U, Mann M. Comparative proteomic phenotyping of cell lines and primary cells to assess preservation of cell type-specific functions. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:443–450. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800258-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou W, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF. Cancer metabolism and mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parks SK, Chiche J, Pouysségur J. Disrupting proton dynamics and energy metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:611–623. doi: 10.1038/nrc3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wise DR, Thompson CB. Glutamine addiction: a new therapeutic target in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goodman M, Bostick RM, Kucuk O, Jones DP. Clinical trials of antioxidants as cancer prevention agents: past, present, and future. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1068–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Gal K, Ibrahim MX, Wiel C, Sayin VI, Akula MK, Karlsson C, Dalin MG, Akyürek LM, Lindahl P, Nilsson J, Bergo MO. Antioxidants can increase melanoma metastasis in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:308re8. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Busiello RA, Savarese S, Lombardi A. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins and energy metabolism. Front Physiol. 2015;6:36. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li X, Fang P, Mai J, Choi ET, Wang H, Yang XF. Targeting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species as novel therapy for inflammatory diseases and cancers. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song C, Appleyard V, Murray K, Frank T, Sibbett W, Cuschieri A, Thompson A. Thermographic assessment of tumour growth in mouse xenografts. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1055–1058. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10:789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. 2015;347:78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1260825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rozhok AI, Wahl GM, De Gregori J. A critical examination of the "bad luck" explanation of cancer risk. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:762–764. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashford NA, Bauman P, Brown HS, Clapp RW, Finkel AM, Gee D, Hattis DB, Martuzzi M, Sasco AJ, Sass JB. Cancer risk: role of environment. Science. 2015;347:727. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jacob F, Monod J. Genetic regulatory mechanisms in the synthesis of proteins. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:318–356. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(61)80072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drake JW. A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7160–7164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kohanski MA, DePristo MA, Collins JJ. Sublethal antibiotic treatment leads to multidrug resistance via radical-induced mutagenesis. Mol Cell. 2010;37:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Long H, Miller SF, Strauss C, Zhao C, Cheng L, Ye Z, Griffin K, Te R, Lee H, Chen CC, Lynch M. Antibiotic treatment enhances the genome-wide mutation rate of target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E2498–2505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601208113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nair CG, Chao C, Ryall B, Williams HD. Sub-lethal concentrations of antibiotics increase mutation frequency in the cystic fibrosis pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2013;56:149–154. doi: 10.1111/lam.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang C, Cao S, Toole BP, Xu Y. Cancer may be a pathway to cell survival under persistent hypoxia and elevated ROS: a model for solid-cancer initiation and early development. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2001–2011. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weinberg RA. Coming full circle-from endless complexity to simplicity and back again. Cell. 2014;157:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhu J, Nie S, Wu J, Lubman DM. Target proteomic profiling of frozen pancreatic CD24+ adenocarcinoma tissues by immuno-laser capture microdissection and nano-LC-MS/MS. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:2791–2804. doi: 10.1021/pr400139c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiśniewski JR, Duś-Szachniewicz K, Ostasiewicz P, Ziółkowski P, Rakus D, Mann M. Absolute proteome analysis of colorectal mucosa, adenoma, and cancer reveals drastic changes in fatty acid metabolism and plasma membrane transporters. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:4005–4018. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Danda R, Ganapathy K, Sathe G, Madugundu AK, Ramachandran S, Krishnan UM, Khetan V, Rishi P, Keshava Prasad TS, Pandey A, Krishnakumar S, Gowda H, Elchuri SV. Proteomic profiling of retinoblastoma by high resolution mass spectrometry. Clin Proteomics. 2016;13:29. doi: 10.1186/s12014-016-9128-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brandi J, Dando I, Pozza ED, Biondani G, Jenkins R, Elliott V, Park K, Fanelli G, Zolla L, Costello E, Scarpa A, Cecconi D, Palmieri M. Proteomic analysis of pancreatic cancer stem cells: functional role of fatty acid synthesis and mevalonate pathways. J Proteomics. 2017;150:310–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]