Abstract

Alcohol use and sexual behavior are important risk behaviors in adolescent development, and combining the two is common. The reasoned action approach is used to predict adolescents’ intention to combine alcohol use and sexual behavior based on exposure to alcohol and sex combinations in popular entertainment media. We conducted a content analysis of mainstream (n=29) and Black-oriented movies (n= 34) from 2014 and 2013–2014, respectively, and 56 television shows (2014–15 season). Content analysis ratings featuring character portrayals of both alcohol and sex within the same 5-minute segment were used to create exposure measures that were linked to online survey data collected from 1,990 14–17 year-old adolescents (50.3% Black, 49.7% White, 48.1% female). Structural equation modeling and group analysis by race were used to test whether attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioral control mediated the effects of media exposure on intention to combine alcohol and sex. Results suggest that for both White and Black adolescents, exposure to media portrayals of alcohol and sex combinations is positively associated with adolescents’ attitudes and norms. These relationships were stronger among White adolescents. Intention was predicted by attitude, norms, and control, but only the attitude-intention relationship was different by race group (stronger for Whites).

Keywords: adolescents, alcohol, drinking, sexual behavior, co-occurrence, media

Introduction

Adolescence is a period of developmentally normative heightened experimentation. Nevertheless, more adverse forms of risk behaviors initiated during this time may continue into adulthood and result in adverse long term outcomes (Kann et al., 2014). Adolescent behavioral research usually focuses on a specific behavior (e.g., alcohol consumption) but risk behaviors frequently co-occur with one another (Brener & Collins, 1998; DuRant, Smith, Kreiter, & Krowchuk, 1999; Hair, Park, Ling, & Moore, 2009; Richard Jessor, 1991). In particular, studies have shown a relationship between sexual activity and alcohol use (Carpenter, 2005; Cooper, 2002; Willoughby, Chalmers, & Busseri, 2004).

Alcohol use prior to or during sexual activity may lead to riskier sex (Carpenter, 2005; Cooper, 2002). The concurrent use of alcohol and sexual activity is associated with several risk factors for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection (STI), such as multiple partners (Santelli, Robin, Brener, & Lowry, 2001; Yan, Chiu, Stoesen, & Wang, 2007) and unprotected sexual intercourse (Baskin-Sommers & Sommers, 2006). These relationships tend to be stronger among female adolescents compared to males, and among white adolescents compared to African-American, Hispanic or Asian groups (Ritchwood, Ford, DeCoster, Sutton, & Lochman, 2015). Adolescent and young adults (ages 15–24) are disproportionately burdened by STIs, and comprise approximately 50% of incident infections (Satterwhite et al., 2013).

When alcohol and sex are used concurrently, it is referred to as “situational co-occurrence” (Cooper, 2002). The behaviors occur at the same time or on the same occasion. For example, according to 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015), 20.6% of surveyed high school students who were sexually active reported drinking alcohol or using drugs before their most recent sexual intercourse. However, behavioral co-occurrence can be global or situational (Cooper, 2002). “Global overlap” (Leigh & Stall, 1993) refers to the extent to which an individual performs both behaviors (e.g., an individual who both drinks alcohol and has sex), and whether there is an increase in the likelihood of performing one based on the performance of the other (Cooper, 2002). Global co-occurrence of alcohol use and sex is also problematic, but does not necessarily confer the same immediate risks as a sexual encounter influenced by intoxication.

Content analyses of popular media such as movies and television demonstrate that these behaviors tend to cluster onscreen just as they often do in adolescent behavior (Bleakley, Romer, & Jamieson, 2014; Flynn, Morin, Park, & Stana, 2015). Despite the widespread popularity of social media, television and film content remain an important source of envrionmental influences. According to national estimates of adolescents’ media use, television continues to dominate the time that they spend with media (Rideout, 2015). Eighty-one percent of teens report watching television daily, and those teens spend on average 3 hours and 15 minutes doing so. In comparison, 58% of teens report using social media daily and of those who use social media, they do so for about 2 hours per day. There are also large racial differences in the time spent watching television daily: Whites who watch TV spend about 2 hours and 56 minutes per day, compared to 4 hours and 33 minutes reported by Black TV users.

In this study, we use the reasoned action approach, based on the Integrative Model of Behavioral Change and Prediction (Fishbein et al., 2001), to examine adolescents’ intention to combine alcohol and sexual activity at the same time or on the same occasion, i.e, situational co-occurrence. The behavior of interest is therefore the act of combining these behaviors – not the behaviors of drinking alcohol and having sex as separate outcomes. We focus on investigating predictors of intention to combine alcohol use and sex (i.e., attitude, normative pressure, and control) and also how exposure to onscreen (television and movies) portrayals of sex and alcohol combinations is related to these constructs. Media exposure has been used as a background variable in previous applications of the reasoned action approach to explain adolescent sexual behavior (Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2011; Gottfried, Vaala, Bleakley, Hennessy, & Jordan, 2013), but its utility in examining situational combinations, and particularly the combination of alcohol and sex, has not yet been determined.

The relationship between alcohol use and sex

There are several explanations for the relationship between alcohol use and sexual activity. The idea of a “problem behavior syndrome” (R. Jessor & Jessor, 1977) serves as the foundation for much of the research in this area. It conceptualizes the behaviors co-occurring on a global level and is based on the premise that there is a single trait that explains the interrelationships among health risk behaviors that is a caused by a “tendency toward deviance or unconventionality” (Donovan & Jessor, 1985; Willoughby et al., 2004). Although there is partial empirical support for a syndrome as an underlying cause of risky problem behaviors (Hair et al., 2009; Willoughby et al., 2004; Zweig, Lindberg, & McGinley, 2001) it is also the case that individual behavior can vary based on situation and contextual factors (Byrnes, 2003), and individual-level moderating factors such as gender and age (Willoughby et al., 2004).

Theories of situational co-occurrence of alcohol and sex, on the other hand, tend to focus on alcohol use causing sexual activity and/or risky sexual activity. There are primarily two mechanisms through which this can occur (Carpenter, 2005; Cooper, 2002). The first is through alcohol’s effects on information processing. According to alcohol myopia theory (Steele & Josephs, 1990), alcohol can affect a particular behavior by blocking or reducing access to salient cues that would typically inhibit that behavior. Alcohol affects one’s ability to engage in further processing and what is referred to as “response conflict”, when a response is the result of weighing salient cues against inhibitory cues. For example, if one were sober, the desire for unprotected sex may also be met by cues such as possible negative consequences (e.g. a sexually transmitted infection) that would result in avoiding unprotected sex. Alcohol myopia would hinder processing to the point where inhibitory cues would not be as influential during intoxication.

The second mechanism through which alcohol can affect sexual behavior is based on expectancies related to alcohol and sex (Fromme, Katz, & Rivet, 1997; Lang, 1985). An individual’s beliefs that alcohol use may lead to, or encourage, sexual behavior “in the manner of a self-fulfilling prophecy” (Cooper, 2002). Those with the expectation that alcohol leads to sex will be more likely to have sex following alcohol consumption (Fromme, D’Amico, & Katz, 1999). In other words, “expectancy provides an attributional excuse to engage in desired but socially prohibited acts” (Hull & Bond, 1986). Both alcohol myopia and relevant expectancies are supported in previous research, and it is likely that a combination of the pathways that predicts the situational co-occurrence of alcohol use and sex. But regardless of the causal nature of the relationship between alcohol use and sexual behavior, these two behaviors often co-occur situationally in adolescent and emerging adult (e.g, college student) populations. The use of the reasoned action approach in this study to examine the combination of alcohol and sex is consistent with the idea of expectancies explaining one’s decision to use alcohol and engage in sexual activity. This approach assumes that behavioral beliefs about what may or may not happen when these two behaviors are combined in a particular situation underlie the constructs relevant to intention formation: attitudes, normative pressure, and self-efficacy/control. Of particular interest is the role of exposure to media risk portrayals as a predictor of such risky intentions and behaviors. Media exposure has been found to play a role in adolescent expectancy formation and risk behavior across multiple behavioral domains (Strasburger, Jordan, & Donnerstein, 2010).

Media effects on risk behavior

Studies have linked exposure to specific media content featuring risk to adolescent behavior in areas such as smoking initiation (Sargent et al., 2005), alcohol use (Dal Cin, Worth, Dalton, & Sargent, 2008), sex (Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2008; Brown et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2004), and violence (Anderson et al., 2003). This body of research, however, has focused on linking one particular type of content with corresponding behavior whereas in the current study we focus on the combination of two prevalent behaviors: alcohol and sex. Regardless of the behavioral focus (singular versus combinations), a number of theories explain why and how media affect behavior. Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) (A Bandura, 1977) posits that children and adolescents learn from media and that learning is likely to be translated into behavior when (a) the role model is similar to the viewer (e.g., gender matched), (b) the behavior and/or context are realistic, (c) the role model is attractive, and (d) the behavior is positively reinforced (A. Bandura, 1994). SCT suggests that adolescents seeing others in the media enjoying risk behaviors have an increased probability of observational learning and behavioral imitation. This effect takes place through processes of “priming” or acceptance of stereotypes and schemas (L.M. Ward, 2003; L.M. Ward & Friedman, 2006) and scripts (Eggermont, 2006; Huesmann LR, 1988). The reasoned action approach can also be used to explain the effects of media content on behavior because the behavioral, normative, and control beliefs that guide behaviors are learned from direct experience or from significant others. Prior research has provided strong support for the utility of a reasoned action approach as a basis for predicting and explaining media’s influence on adolescent sexual behavior (Bleakley et al., 2011).

It is important to note that strength of media effects tend to vary by racial group. In particular, the relationship between media exposure and behavior is typically stronger among white adolescents compared to Black adolescents, as evidenced by studies on smoking initiation (Dal Cin, Stoolmiller, & Sargent, 2013) and sexual behavior (Hennessy, Bleakley, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2009). Given the various mechanisms through which media effects operate, it is necessary to examine differential media effects more closely to better understand when the relationship varies in way that could explain health and behavioral disparities. It is hypothesized that one reason for this observed difference might be that studies linking media content and behavior with Black adolescents focus too much on mainstream content and fail to capture the media content that Black adolescents are actually using (Dal Cin et al., 2013; Ellithorpe & Bleakley, 2016). Therefore, in the present study we include film and television content popular with Black adolescents in addition to those with mainstream popularity.

The Reasoned Action Approach

Reasoned action is a psychosocial model of behavior explanation and prediction that is a synthesis of the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), Social-Cognitive Theory (A. Bandura, 1986), the Health Belief Model (Janz & Becker, 1984), and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, 1992). It has been applied in numerous studies to understand and predict outcomes such as condom use, sexual behaviors, alcohol use and binge drinking, and many others (Ajzen, 2015). As noted, reasoned action has also been used to demonstrate how exposure to sexual media affects adolescent sexual behavior; such content increased perceived norms about similar other engaging in sexual behavior (Bleakley et al., 2011).

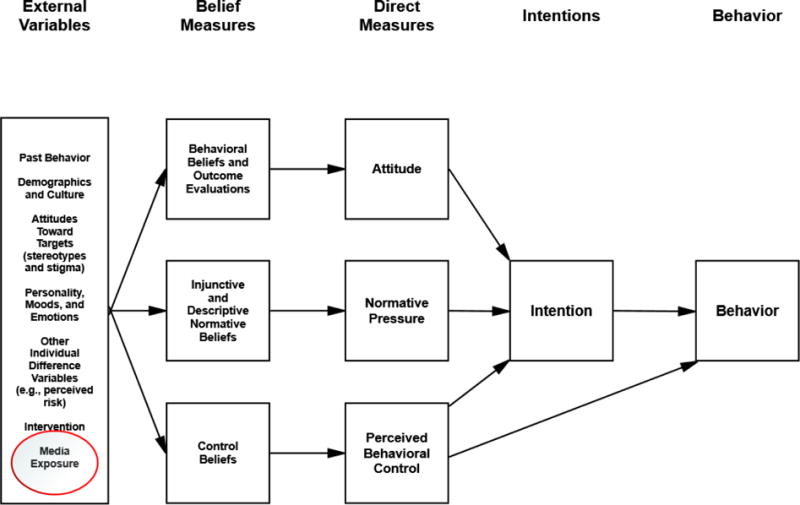

As shown in Figure 1, the focus of reasoned action is one’s intention to perform a specific behavior (the “target behavior”) as both a dependent variable and as a predictor of behavior. That is, the model is concerned with the factors influencing intention formation as well as with the relationship between intention and subsequent performance of the target behavior (Kim & Hunter, 1993). The model assumes that behavior is primarily determined by intentions, although one may not always be able to act on one’s intentions because environmental factors and/or a lack of skills and abilities.

Figure 1.

Generic Model for Reasoned Action Approach

Intention to perform the target behavior (in this case, combining alcohol and sex) is a function of one’s attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) specific to performing the behavior of interest. Attitudes reflect one’s favorableness or unfavorableness towards personally performing the behavior. Normative pressure is based on both injunctive and descriptive norms. Injunctive norms refer to perceptions about what others think one should do with regard to performing the behavior by emphasizing normative approval or disapproval. Descriptive norms, however, focus on perceptions of what others do with regard to performing the behavior. Perceived behavioral control is similar to the construct of self-efficacy, and is based on one’s perceptions about his or her ability and capacity to perform the behavior assuming that one wanted to do so.

Specific beliefs underlie all three of the predictors of intention. For example, attitudes are determined by one’s beliefs that performing the behavior will lead to certain positive or negative consequences while normative pressure beliefs identify the specific referent others who support the respondent’s intention to perform the target behavior and also those who are perceived as performing the behavior themselves. Note that in the reasoned action approach, background variables such as personality traits (e.g., sensation seeking), demographic characteristics, and media exposure are expected to influence behavior only indirectly; their effects on intention are assumed to be mediated by the more proximal variables of attitudes, normative pressure, and control (Hennessy et al., 2010). Exposure to particular media content is therefore treated as a background variable that affects intention (and ultimately behavior) by affecting the underlying beliefs and the corresponding constructs. These mediating relationships are depicted in Figure 1.

Study Hypotheses

Using media exposure to risk as a background variable, we conduct a mediational analysis of such exposure on intention to combine alcohol use and sex based on the generic theoretical model shown in Figure 1 (using only the direct measures and not the underlying beliefs). We hypothesize that the association between exposure to co-occurring alcohol and sex media content and intention to combine these behaviors will be mediated by attitudes, normative pressure, and PBC. Given the lack of theoretical testing on the combination alcohol use and sexual activity as a behavior, we cannot predict which construct(s) will be most strongly associated with risky media exposure and which construct(s) will be most strongly related to intention. We also consider participant race (White and Black/African American) as a moderating factor but with the inclusion of media content popular specifically with Black youth, we are unable to make predictions about the magnitude of exposure effects on attitude, normative pressue, and control for either group.

Methods

Content Analysis Sample

Television shows

Nielsen statistics for adolescents aged 14–17 were used to determine the television shows from the 2014–2015 season (from September 22, 2014 and June 28, 2015) that would be coded. The lists were separated by Black and non-Black adolescents because Black and non-Black adolescents tend to watch different kinds of shows (Ellithorpe & Bleakley, 2016), with the final goal being lists of the top 30 shows watched by Black adolescents and the top 30 shows watched by non-Black adolescents (including primarily white viewers, but also Hispanic, Asian, and others). Only narrative television content with primarily human characters was included. Old shows airing repeat episodes and syndicated shows were also included, but only when the number of repeats aired were equivalent to at least of one season of that show.

Creating the episode pool

The top 30 shows for Blacks and the top 30 for non-Blacks were selected for coding; four shows appeared on both lists, thus 56 shows were coded. The season of each show that aired in 2014–2015 was obtained for inclusion in the coding pool, with the exception of a handful of shows in syndication or reruns (e.g., How I Met Your Mother) in which case the last season produced was coded. Either 3 or 5 episodes were randomly selected from each season for coding (Manganello, Franzini, & Jordan, 2008). If a show had ten or fewer episodes in the 2014–2015 season, 3 episodes were randomly selected (n=5, 8.93% of shows). If a show had more than ten episodes that season, 5 episodes were randomly selected (n=47, 83.93% of shows). If a show had a 15-minute runtime, six episodes were selected to equate the amount coded to a half-hour show (n=4, 7.14% of shows).

Films

While adolescent viewing data was not available for the study’s films, adolescents are over represented in terms of movie box office sales and Blacks are comparable to Whites in per capita box office attendance (Motion Picture Association of America, 2014). Therefore, the sample taken was of top-grossing films (for mainstream viewership) and of Black-oriented films (for Black viewership). The top 30-grossing films of 2014 according to Variety magazine were selected as representing popular mainstream films. For the purposes of the present study, Black-oriented films were defined as those where Black actors comprised 50% or greater of the main characters and/or a narrative theme of race, racism, or Black culture (Schooler, 2008; Schooler, Ward, Merriwether, & Caruthers, 2004). Of the top 500 films for 2013 and 2014 (1,000 total) according to www.boxofficemojo.com, 30 films from 2013 and 19 films from 2014 were selected. Three films that did not have predominantly Black casts but covered Black or racial themes (Allen, Dawson, & Brown, 1989; Sheridan, 2006) were added to the list (42 (38% Black cast), 12 Years a Slave (29% Black cast), and Fruitvale Station (33% Black cast)). Finally, one film that was originally coded with the mainstream films (Ride Along) met the criterion for a predominately Black cast (50%). Thus the final sample included 29 mainstream films and 34 Black-oriented films.

Content Coding Procedures

The selected television episodes and films were coded by trained coders in five-minute segments. Intercoder reliability was achieved using a test sample of 59 film and television segments before coding the selected sample independently. Each segment was coded for the portrayal of alcohol and sex, including which character was involved in the behavior. Krippendorff’s Alpha was calculated as a measure of reliability for identifying the presence of each behavior in a segment. Alcohol portrayal was defined as a character being directly involved any activity related to alcohol, ranging from handling of bottles to observed consumption (Krippendorff’s α=0.94). Sexual content was defined as any type of sexual contact, ranging from kissing on the lips to explicit intercourse (Krippendorff’s α=0.93). This coding scheme has been used and validated in previous research (Bleakley, Jamieson, & Romer, 2012; Bleakley et al., 2014; Nalkur, Jamieson, & Romer, 2010).

Combinations of alcohol and sex

A combination of alcohol and sex was coded as having occurred when the same character was coded as portraying both alcohol use and sexual behavior in the same five-minute segment. The number of segments containing a portrayal of the alcohol and sex combination for each television show or film were then divided by the total number of segments coded for that show or film to create a measure of the proportion of content that involved the combination of alcohol and sex.

Online Survey

Participants

Participants were 2,432 adolescents aged 14–17 years who were recruited from opt-in panels through the online survey company GfK (for more information see http://www.gfk.com/) between November 13, 2015 and December 14, 2015. More than three-quarters of the respondents (76%) were recruited through their parents, and the remaining were recruited directly. Potential respondents were screened for whether they were a teen aged 14–17, a parent of a teen aged 14–17, or not eligible. Parents of teens were asked to consent for their child to participate before being asked to bring their teen to complete the rest of the survey. All teens were given assent information before beginning the survey and received points through the survey panel for their participation. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the sponsoring institution.

Eight participants who indicated a sex of “other” were removed from analysis, leaving 2,424 participants (1,167 or 48.14% female). Black participants were oversampled for a roughly equal sample of Black and White respondents. For the purposes of racial group comparison in the present analysis, only non-Hispanic Black (n=1000) and non-Hispanic White (n=990) participants were included (total n=1,990). The median survey time was 26.7 minutes. All of the demographic information that follows is based only on the White (49.8%) and Black (50.2%) respondents used in this analysis. The age breakdown for these respondents was evenly divided by age: 14 years (21.3%), 15 years (25.7%), 16 years (26.0%), and 17 years (27.0%). Almost 47% of the sample reported receiving free lunch at school and 42.9% of the sample reported that their mother graduated from college or held a graduate degree. Most respondents (41.7%) reported taking the survey on a laptop computer, followed by either a desktop computer (24.2%), a smartphone (23.6%), or a tablet (9.6%).

Survey Measures

Media exposure

Participants were asked to indicate how often they watched each coded television show in the past year, on a scale from 0=never to 3=often (M=0.68, SD=0.54). For films participants indicated whether they had seen each film never (0), once (1), or more than once (2); M=0.44, SD=0.33).

Exposure to alcohol and sex

Exposure to the combination of alcohol and sex was operationalized by multiplying the proportion of segments for each television show or film containing the combination by each participants’ self-reported exposure to the show or film. These scores were then summed across all shows to create a measure of total exposure to alcohol and sex in television (M=1.02, SD=0.84, range=0.00–4.11), and summed across all films to create a measure of total exposure to alcohol and sex in film (M=0.75, SD=0.82, range=0.00–4.43). The standardized (z-score) versions of the measures were created and then summed together to create a measure of overall screen exposure to alcohol and sex (M=0.00, SD=1.80, range=−2.12 to 8.19). This approach has been used in previous studies (Bleakley, Fishbein, et al., 2008; Bleakley, Hennessy, et al., 2008; Bleakley et al., 2011; Hennessy et al., 2009).

Reasoned action constructs

The following measures pertain to the RAA (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Participants were provided with the following explanation of the combination before answering the theory measures, “The questions below are about drinking alcohol and having sex. When we say “drinking alcohol and having sex,” we mean doing them together or around the same time. For example, having one or more drinks before or during sexual intercourse.” Drinking alcohol was defined by: “When we say ‘drinking alcohol’, we mean having at least one drink of alcohol. In this survey, a ‘drink of alcohol’ is one 12 oz. can or bottle of beer, or one 4 oz. glass of wine, or one mixed drink, or one shot of liquor.”

Attitude

My drinking alcohol and having sex in the next 6 months would be… bad/good, foolish/wise, not enjoyable/enjoyable, unpleasant/pleasant, boring/exciting, harmful/beneficial, and unplanned/planned (scale 1 to 7; M=2.46, SD=1.64, Cronbach α= .84).

Normative pressure

Do most people who are important to you think that you should not/should drink alcohol and have sex in the next 6 months (scale 1, Should not combine to 7, Should combine; M=1.57, SD=1.33)? Will most people like you drink alcohol and have sex in the next 6 months (scale 1, Will not combine to 7, Will combine; M=2.28, SD=1.83)? Each was entered into the model separately as two aspects of normative pressure (McEachan et al., 2016).

Control

If I really wanted to I am certain that I could drink alcohol and have sex in the next 6 months; It is completely up to me if I drink alcohol and have sex in the next 6 months (scale 1, Strongly disagree to 7, Strongly agree; M=4.59 SD=2.00).

Behavioral Intention

How likely is it that you will drink alcohol and have sex in the next 6 months (scale 1, Extremely unlikely to 7, Extremely likely; M=1.79, SD=1.54)?

Sensation seeking

Sensation-seeking was measured using the four-item brief sensation seeking scale (range 1 to 5, M=3.29, SD=1.00, Cronbach α = . 87)(Stephenson, Hoyle, Palmgreen, & Slater, 2003).

Daily TV time

We calculated a measure of daily hours of TV time but asking participants to indicate how many hours they spent watching television in the previous day in three times periods: from wake until before noon, between noon and 6pm, and after 6pm. In order to have a maximum of 24 hours, responses greater than six hours for the time period between noon and 6pm (n=41, 2.09%) were recoded as 6 hours, and responses greater than nine hours were recoded as nine for the other two time periods (before noon n=28, 1.42%; after 6pm n=15, 0.08%). Responses were then summed to create a measure of average hours per day (M=5.50, SD=4.61; Median=4.5).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted on all variables, as well as bivariate correlational analyses on the theoretical constructs, exposure variables, and relevant covariates. Structural equation modeling in Stata 13 was used to test the theoretical model using group analysis by race. Group differences were tested using Wald tests.

Results

Correlations between media exposure and reasoned action mediators

Correlations between exposure to onscreen alcohol and the reasoned action constructs, as well as sensation seeking and daily TV time, are presented by race group in Table 1. Note that the correlations between onscreen sex and alcohol and all the reasoned action constructs (except control) appear stronger for White adolescents compared to Black adolescents. Also, for Black adolescents, daily TV time is not significantly correlated with intention to combine sex and alcohol use, but is related to intention (r=.15) among White adolescents (although the correlation between the content-specific exposure and intention is stronger (r=.32).

Table 1.

Correlations of reasoned action constructs, media exposure, and covariates, by race group

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Exposure to alcohol and sex combination onscreen | – | .32 | .27 | .34 | .27 | .03 | .22 | .32 |

| 2. Intention | .15 | – | .65 | .50 | .52 | .22 | .24 | .15 |

| 3. Attitude | .12 | .51 | – | .49 | .49 | .19 | .27 | .08 |

| 4. Injunctive norm | .08 | .47 | .40 | – | .48 | .07 | .20 | .19 |

| 5. Descriptive norm | .10 | .52 | .39 | .56 | – | .29 | .22 | .15 |

| 6. Perceived behavioral control | .03 | .21 | .18 | .10 | .28 | – | .11 | .00 |

| 7. Sensation seeking | .13 | .11 | .12 | .05 | .07 | .16 | – | .08 |

| 8. Daily TV time | .22 | .06 | .01 | .01 | .01 | −.01 | .07 | – |

Bolded values are significant at the p<.05 level or less.

The coefficients below the diagonal (shaded) are Black adolescents; the coefficients above the diagonal are White adolescents.

Relationship between media exposure and attitude, norms, and control

An initial group invariance test between White and Black participants suggested that most paths from background variables (i.e., daily TV time, sensation seeking, age, and sex) to the mediators were equal between groups, with the exception of sensation seeking in predicting attitudes, and of daily TV time predicting injunctive and descriptive norms. All three paths were stronger for White participants than for Black participants. The remaining paths were constrained to be equal across groups for the subsequent analyses to enhance parsimony; this constraining did not cause meaningful differences in the results.

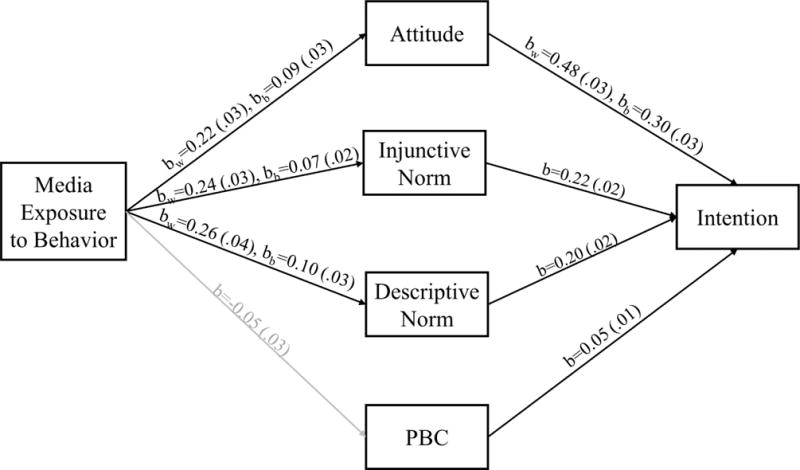

Fit statistics and the regression results are in Figure 1. Unstandardized coefficients are reported because comparing standardized coefficients between groups in a multiple group analysis is misleading due to differential variance adjustments (Arnold, 1982; Kline, 2011). When there were no significant path differences, the effect holding the paths constant across groups is reported. Regression coefficients for the covariates on reasoned action mediators can be found in Table 2. Exposure to onscreen alcohol and sex co-occurrence was significantly associated with attitudes, injunctive norms, and descriptive norms among both White and Black adolescents, but not significantly related to control. The effect of exposure was significantly greater for White adolescents compared to Black adolescents for all three constructs: attitude χ2(1)=10.23, p=.001, injunctive norms (injunctive: (χ2(1)=23.92, p<.001) and descriptive norms χ2(1)=10.85, p=.001).

Table 2.

Unconstrained unstandardized regression coefficients of covariates in predicting reasoned action mediators

| Reasoned Action Mediators

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Injunctive Norms | Descriptive Norms | Control | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Variable | All n=1990 b (se) |

White n=990 b (se) |

Black n=1000 b (se) |

All n=1990 b (se) |

White n=990 b (se) |

Black n=1000 b (se) |

All n=1990 b (se) |

White n=990 b (se) |

Black n=1000 b (se) |

All n=1990 b (se) |

White n=990 b (se) |

Black n=1000 b (se) |

| Daily TV time | −0.01 (.01) |

– | – | 0.01 (.01) |

0.03 (.01)* |

−0.01 (.01) |

0.01 (.01) |

0.03 (.01)* |

−0.01 (.01) |

−0.01 (.01) |

– | – |

| Age | 0.15 (.03)* |

– | – | 0.05 (.03)* |

– | – | 0.16 (.04)* |

– | – | 0.24 (.04)* |

– | – |

| Female | −0.58 (.07)* |

– | – | −0.11 .06)* |

– | – | −0.35 (.08)* |

– | – | −0.01 (.09) |

– | – |

| Sensation Seeking | 0.26 (.03)* |

0.30 (.04)* |

0.20 (.05)* |

0.10 (.03)* |

– | – | 0.23 (.04)* |

– | – | 0.30 (.05)* |

– | – |

p<.05 of less.

Coefficients by race group provided when there was a statistically significant difference between groups.

Relationship between attitude, norms, and control on intention

Figure 1 also depicts the relationships of the mediating constructs to intention. Attitude toward combining alcohol use and sex was associated with one’s intention for both White and Black adolescents, with a significantly greater association among Whites (χ2(1)=23.21, p<.001). Injunctive norms, descriptive norms, and control were also all related to intention, and there were no differences by race on any of these paths. Standardized coefficients indicate that intention to combine alcohol use and sex was mostly strongly related to attitude for both Whites (β=0.46, p<.001) and Blacks (β=0.32, p<.001), compared to the effect of injunctive (β=0.19, p<.001), descriptive norms (β=0.23, p<.001), and control (β=0.06, p<.001). Variance explained by the model in intention to combine alcohol and sex was R2=.50 for Whites and R2=.40 for Blacks.

Discussion

The situational co-occurrence of alcohol use and sexual activity among adolescents is associated with riskier sexual practices (e.g., multiple sex partners and unprotected sex) that can increase an adolescent’s likelihood of acquiring an STI (Baskin-Sommers & Sommers, 2006; Santelli et al., 2001; Yan et al., 2007). The reasoned action approach provides a useful model for examining adolescents’ cognitions as they pertain to combining these behaviors, and also builds on previous studies that point to individuals’ expectancies as contributing factors to situational co-occurrence. Our results demonstrate that combining alcohol use and sex is a behavioral outcome that can be explained and predicted by intention and as a function of one’s attitude, norms, and control. Black and White adolescents showed largely similar effects in terms of the relationships among the reasoned action mediators and intention, with the exception that attitudes are more strongly associated with intention to combine alcohol and sex for White adolescents. The model presented here also demonstrates how attitude and norms (but not control) mediate the effect of exposure to onscreen portrayals of alcohol and sex combinations in television and movies. In addition, even when media content poplar with Black teens are included in the sample, White adolescents are still more vulnerable to influence from what they see onscreen.

The use of reasoned action to examine the combination of two risk behaviors is a novel application of a theoretical framework that is based on the premise of behavioral correspondence and specificity. By conceptualizing the co-occurrence of alcohol use and sexual activity as a singular behavioral outcome, it becomes possible to elicit expectancies and other beliefs specific to performing these behaviors in conjunction with one another. Expectancies about drinking and having sex in a particular situation may be different than expectancies associated with each singular behavior, and research is needed to understand the beliefs that underlie one’s decision to combine these risky behaviors.

Critics of this approach might assert that sexual activity following alcohol use is not necessarily a planned, “reasoned”, or “rational” behavior that can be explained through a cognitive model of behavior. The idea that the reasoned action approach relies on “rationality” is a common misunderstanding, which leads to two fundamental errors (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). First, some critics assume that the cognitive processing of the underlying beliefs must be “rational”, although the definition of “rational processing” is not well articulated. However, reasoned action simply assumes that the three types of belief constructs predict intention and that intention is the primary determinant of behavior. It does not describe how these beliefs actually form, thus there is no assumption that underlying beliefs form intention in a “rational” way. The second error is the assertion that the beliefs need to be accurate or have empirical truth value, which is not the case (see Hennessy, Delli Carpini, Blank, Wennig, & Jamieson, 2015 for how beliefs about the paranormal, the search for Bigfoot, or the background of American presidents predict voting intention in the US). The reasoned action approach, however, is concerned with volitional behavior, meaning that unless using alcohol and engaging in sex are not under the volitional control of an individual (Fishbein & Ajzen 2010), the reasoned action approach is a promising way to view situational co-occurrence of alcohol and sex and other behaviors as well (aggression and alcohol use), with implications for intervention design.

As demonstrated here, one factor shaping relevant expectancies and beliefs is exposure to media content that features onscreen combinations of alcohol and sex. In our analyses we demonstrate that an adolescent’s attitude and normative beliefs were positively associated with their media exposure. Adolescents are seeing content that is resulting in favorable evaluations of performing the behavior, increased notions that people like them are also combining sex and alcohol, and that important others may approve of them engaging in the alcohol/sex combination. According to Social Cognitive Theory, characters in media programming act as models for behavior, resulting in a process of observational learning which may culminate in the adolescent adopting the scripts, beliefs, and/or behaviors enacted by the character(s) (A. Bandura, 1994). This process is particularly relevant for the many adolescents who lack their own experience to draw on, thus potentially giving more weight to what are they are exposed to through their media choices.

A stronger relationship was found between media exposure and adolescents’ cognition about alcohol and sex combinations among White adolescents compared to their Black counterparts. This finding is consistent with other studies that show stronger media effects among White youth ((Dal Cin et al., 2013; Hennessy et al., 2009), although typically media content popular with Black youth is not included in the media samples as it was here. It is possible that because White adolescents tend to initiate alcohol use and sexual activity later than their Black peers (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015), their lack of real-world experience results in greater learning from external sources. Their vulnerability may also perhaps at least partially due to the fact that mainstream representations in TV and film continue to construct White teens as the prototypical teenager. In other words, White adolescents consistently see themselves in film and television, whereas Black teenagers see themselves less frequently but in more stereotypical roles.

Another possibility is that because Black adolescents spend more than 1.5 times more time watching television compared to White teens (Rideout, 2015), perhaps any effect of the content to which they are exposed gets diluted, or they are exposed to content that may present more mixed messages. It could also be the case that Black adolescents are consistently confronted with negative, stereotypical images of themselves in media content and perhaps are critical consumers of media that do not view these representations as realistic (L Monique Ward, Hansbrough, & Walker, 2005). More research is needed to investigate these possibilities more closely. That said, there were still significant relationships between media exposure and outcomes for Black adolescents, just on a lesser scale than for White adolescents.

In contrast to race differences in the exposure-mediator relationships, the relationships between the mediators and intention is consistent across groups. There was only one significant group difference: the effect of attitude on intention such that one’s intention is more attitudinally driven for White adolescents compared to Black adolescents. Interventions therefore can focus on the same constructs for both groups. Perceived behavioral control, while related to intention, had the weakest relationship to intention for both groups (when compared to attitude and both types of norm measures).

Limitations

Adolescents who participated in this survey may be different from other adolescents, such as those who are not enrolled with opt-in survey panels or those who do not have parents who are enrolled in such panels. Because of the online nature of the survey, the adolescents who participated may be more engaged with media than other youth, but the findings here are consistent with previous research in this area. The cross-sectional nature of the data prohibits any causal conclusions about the direction of relationship between media exposure and attitude and norms, however there is a stronger theoretical precedent for modeling intention using attitude, norms, and control as outcomes of media exposure (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Additionally, without a behavioral outcome, we cannot infer if behavior would be affected by media exposure and can only comment on intention. However, numerous meta-analyses that test the intention-behavior relationship demonstrate that “intention has a significant impact on behavior”, although the size of effect varies depending on whether the studies were experimental or correlational in nature (Webb & Sheeran, 2006).

The content analysis has limitations as well. The context of the sexual behavior was not taken in account, and although messages of risk and responsibility are uncommon (Kunkel et al., 2003), it is possible that there were portrayals that discouraged alcohol and sex combinations. Additionally, the way alcohol and sex combinations were operationalized leaves room for the possibility that within the 5-minute segment the behaviors were not in fact linked to one another and merely appeared within the same 5-minute segment but in entirely different scenes. However, we would argue that since the assessments of exposure were based on the same character’s involvement in the behaviors, that if the combination depicted did not reflect situational co-occurrence, the depiction of global co-occurrence is still relevant. Another potential measurement issue to our sexual content measure. We chose to include any sexual activity because it is not necessarily the direct depiction of a particular behavior (e.g., sex intercourse) that can influence the scripts and attitudes, norms, and control around intention to drink and have sex. The sexual scripts and cues present in such media content often include sexual talk and innuendo along with “less risky” sexual activity that has implications for riskier behaviors. Given that most onscreen sexual content is less explicit (e.g., does not directly depict intercourse), any relationship found is still notable and would likely be an underestimate of the association.

Conclusion

Adolescents often combine risk behaviors, both globally and situationally (Cooper, 2002). The combination of alcohol use and sexual behavior on a situational level is of particular interest, as approximately 20.6% of sexually active adolescents reported drinking alcohol or taking drugs using a substance before their most recent sexual intercourse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Previous research has focused on the alcohol and sex combination in order to understand how the behaviors may be mutually reinforcing (Cooper, 2002; Fromme et al., 1999; Steele & Josephs, 1990), but has not examined associations with exposure to media content that features these combinations. Our findings indicate that exposure to this situational combination of alcohol use and sexual behavior seems to play a role in influencing adolescents’ intention to engage in the combination. This is the case for both Black and White adolescents, although the relationship between exposure and the mediators was stronger for White adolescents compared to Black adolescents. Future research should examine how specific expectancies and beliefs about behavioral co-occurrences, which may vary by racial group, are related to risk behavior and the role of media in the development of such beliefs.

Figure 2. Path analysis results (n=1,990).

Note: greyed out path indicates pooled non-significant effect. Group coefficients presented when coefficients were significantly different between White and Black adolescents. Goodness of Fit: χ2(10)=62.8, p<.05, CFI=.99, TLI=.96, RMSEA=.042 (.030, .055). Correlations between error terms of mediating variables not shown for clarity.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the coders and managers for their contributions to this project: Anna Rose Bedrosian, Sebastian Lemus Camacho, Anna Jose, Mia Leyland, Rachel MacDonald, Haley Mankin, and Jaléssa Mungin.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (Grant Number 1R21HD079615). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD.

References

- Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior: A Bibliography: 1985–2015. 2015 Retrieved from http://people.umass.edu/aizen/tpbrefs.html.

- Allen RL, Dawson MC, Brown RE. A schema-based approach to modeling an African-American racial belief system. American Political Science Review. 1989;83:421–441. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1962398. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Berkowitz L, Donnerstein E, Huesmann LR, Johnson JD, Linz D, Wartella E. The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2003;4(3):81–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2003.pspi_1433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold HJ. Moderator variables: A clarification of conceptual, analytic, and psychometric issues. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 1982;29(2):143–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: a Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs: NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In: Bryant J, Zillman D, editors. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers A, Sommers I. The co-occurrence of substance use and high-risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(5):609–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.010. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Hennessy M, Jordan A, Chernin A, Stevens R. Developing respondent based multi-media measures of exposure to sexual content. Communications Methods and Measures. 2008;2(1 & 2):43–64. doi: 10.1080/19312450802063040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, Jordan A. It works both ways: the relationship between exposure to sexual content in the media and adolescent sexual behavior. Media Psychology. 2008;11(4):443–461. doi: 10.1080/15213260802491986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Using the Integrative Model to explain how exposure to sexual media content influences adolescent sexual behavior. Health Education and Behavior. 2011;38(5):530–540. doi: 10.1177/1090198110385775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Jamieson PE, Romer D. Trends of sexual and violent content by gender in top-grossing U.S. films, 1950–2006. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Romer D, Jamieson PE. Violent Film Characters’ Portrayal of Alcohol, Sex, and Tobacco-Related Behaviors. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):71–77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Collins JL. Co-occurrence of health-risk behaviors among adolescents in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;22(3):209–213. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, L’Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C. Sexy media matter: Exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television, and magazines predicts back and white adolescents’ sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1018–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes JP. Changing views on the nature and prevention of adolescent risk taking. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. 2003:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C. Youth alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: evidence from underage drunk driving laws. Journal of Health Economics. 2005;24(3):613–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data website. 2015:1991–2015. Retrieved from http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/

- Collins R, Elliott M, Berry S, Kanouse D, Kunkel D, Hunter SB, Miu A. Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2004;114:280–289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1065-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;supplement(14):101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Stoolmiller M, Sargent JD. Exposure to Smoking in Movies and Smoking Initiation Among Black Youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(4):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.008. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Dalton MA, Sargent JD. Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction. 2008;103(12):1925–1932. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Jessor R. Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(6):890. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Smith JA, Kreiter SR, Krowchuk DP. The relationship between early age of onset of initial substance use and engaging in multiple health risk behaviors among young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153(3):286–291. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont S. Television viewing and adolescents’ judgment of sexual request scripts: a latent growth curve analysis in early and middle adolescence. Sex Roles. 2006;55:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Ellithorpe ME, Bleakley A. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, online first. 2016. Wanting to see people like me? Racial and gender diversity in popular adolescent television. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: A Reasoned Action Approach. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Triandis H, Kanfer F, Becker M, Middlestadt S, Eichler A. Factors influencing behavior and behavior change. In: Baum A, Reveson T, Singer J, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn MA, Morin D, Park SY, Stana A. “Let’s Get This Party Started!”: An Analysis of Health Risk Behavior on MTV Reality Television Shows. Journal of Health Communication. 2015;20(12):1382–1390. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D’Amico EJ, Katz EC. Intoxicated sexual risk taking: An expectancy or cognitive impairment explanation? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(1):54–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Katz EC, Rivet K. Outcome Expectancies and Risk-Taking Behavior. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 1997;21(4):421–442. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA, Vaala SE, Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Jordan A. Does the Effect of Exposure to TV Sex on Adolescent Sexual Behavior Vary by Genre? Communication Research. 2013;40(1):73–95. doi: 10.1177/0093650211415399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair EC, Park MJ, Ling TJ, Moore KA. Risky behaviors in late adolescence: Co-occurrence, predictors, and consequences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45(3):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Brown L, DiClemente R, Romer D, Salazar L. Differentiating between precursor and control variables when analyzing reasoned action theories. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(1):225–236. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9560-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Estimating the longitudinal association between adolescent sexual behavior and exposure to sexual media content. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:586–596. doi: 10.1080/00224490902898736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, Delli Carpini MX, Blank MB, Wennig K, Jamieson KH. Using Psychological Theory to Predict Voting Intentions. Journal of Community Psychology. 2015;43:466–483. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR. An information processing model for the development of aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1988;14(1):13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hull JG, Bond CF. Social and behavioral consequences of alcohol consumption and expectancy: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99(3):347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz N, Becker M. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12(8):597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, Chyen D. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(Suppl 4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Hunter J. Relationships among attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behavior. Communication Research. 1993;20(2):331–364. doi: 10.1177/009365093020003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Third. Guilford press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel D, Biely E, Eyal K, Cope-Farrar K, Donnerstein E, Fandrich R. Sex on TV3: A Biennial Report to the Kaiser Family Foundation (biennial report) Menlo Park, CA: 2003. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Lang AR. The social psychology of drinking and human sexuality. Journal of Drug Issues. 1985;15(2):273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV: Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychologist. 1993;48(10):1035. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden TJ, Ellen PS, Ajzen I. A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18(1):3–9. doi: 10.1177/0146167292181001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manganello J, Franzini A, Jordan A. Sampling television programs for content analysis of sex on TV: how many episodes are enough? Journal of Sex Research. 2008;45(1):9–16. doi: 10.1080/00224490701629514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachan R, Taylor N, Harrison R, Lawton R, Gardner P, Conner M. Meta-Analysis of the Reasoned Action Approach (RAA) to Understanding Health Behaviors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2016:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9798-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motion Picture Association of America. Theatrical Market Statistics. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.mpaa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MPAA-Theatrical-Market-Statistics-2014.pdf.

- Nalkur PG, Jamieson PE, Romer D. The effectiveness of the motion picture association of America’s rating system in screening explicit violence and sex in top-ranked movies from 1950 to 2006. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47(5):440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V. The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. Common Sense Media. 2015 Available at https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/census_researchreport.pdf [Accessed 3 February 2016]

- Ritchwood TD, Ford H, DeCoster J, Sutton M, Lochman JE. Risky sexual behavior and substance use among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review. 2015;52:74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Robin L, Brener ND, Lowry R. Timing of alcohol and other drug use and sexual risk behaviors among unmarried adolescents and young adults. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33(5):200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, Gibson JJ, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Carusi CP, Dalton MA. Exposure to movie smoking: Its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MCB, Weinstock H. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2013;40(3):187–193. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D. Real women have curves: A longitudinal investigation of TV and the body image development of Latina adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23(2):132–153. doi: 10.1177/0743558407310712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D, Ward ML, Merriwether A, Caruthers A. Who’s that girl: Television’s role in the body image development of young white and black women. Psychology of women quarterly. 2004;28(1):38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00121.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan E. Conservative implications of the irrelevance of racism in contemporary African American cinema. Journal of Black Studies. 2006;37(2):177–192. doi: 10.1177/0021934706292347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45(8):921. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson MT, Hoyle RH, Palmgreen P, Slater MD. Brief measures of sensation seeking for screening and large-scale surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;72(3):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasburger VC, Jordan AB, Donnerstein E. Health effects of media on children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):756–767. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM. Understanding the role of entertainment media in the sexual socialization of American youth: A review of empirical research. Developmental Review. 2003;23:347–388. [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM, Friedman K. Using TV as a guide: Associations between television viewing and adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(1):133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ward LM, Hansbrough E, Walker E. Contributions of music video exposure to black adolescents’ gender and sexual schemas. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20(2):143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Webb T, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(2):249–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby T, Chalmers H, Busseri MA. Where is the syndrome? Examining co-occurrence among multiple problem behaviors in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1022. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan AF, Chiu YW, Stoesen CA, Wang MQ. STD-/HIV-related sexual risk behaviors and substance use among US rural adolescents. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(12):1386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig JM, Lindberg LD, McGinley KA. Adolescent health risk profiles: The co-occurrence of health risks among females and males. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30(6):707–728. [Google Scholar]