Abstract

Pomegranate has two types of flowers on the same plant: functional male flowers (FMF) and bisexual flowers (BF). BF are female-fertile flowers that can set fruits. FMF are female-sterile flowers that fail to set fruit and that eventually drop. The putative cause of pomegranate FMF female sterility is abnormal ovule development. However, the key stage at which the FMF pomegranate ovules become abnormal and the mechanism of regulation of pomegranate female sterility remain unknown. Here, we studied ovule development in FMF and BF, using scanning electron microscopy to explore the key stage at which ovule development was terminated and then analyzed genes differentially expressed (differentially expressed genes – DEGs) between FMF and BF to investigate the mechanism responsible for pomegranate female sterility. Ovule development in FMF ceased following the formation of the inner integument primordium. The key stage for the termination of FMF ovule development was when the bud vertical diameter was 5.0–13.0 mm. Candidate genes influencing ovule development may be crucial factors in pomegranate female sterility. INNER OUTER (INO/YABBY4) (Gglean016270) and AINTEGUMENTA (ANT) homolog genes (Gglean003340 and Gglean011480), which regulate the development of the integument, showed down-regulation in FMF at the key stage of ovule development cessation (ATNSII). Their upstream regulator genes, such as AGAMOUS-like (AG-like) (Gglean028014, Gglean026618, and Gglean028632) and SPOROCYTELESS (SPL) homolog genes (Gglean005812), also showed differential expression pattern between BF and FMF at this key stage. The differential expression of the ethylene response signal genes, ETR (ethylene-resistant) (Gglean022853) and ERF1/2 (ethylene-responsive factor) (Gglean022880), between FMF and BF indicated that ethylene signaling may also be an important factor in the development of pomegranate female sterility. The increase in BF observed after spraying with ethephon supported this interpretation. Results from qRT-PCR confirmed the findings of the transcriptomic analysis.

Keywords: bisexual flowers, functional male flowers, female sterility, Punica granatum L., transcriptomic analysis

Introduction

Female sterility is a widespread phenomenon in various plants, such as Arabidopsis (Robinson-Beers et al., 1992), tomato (Honma and Phatak, 1964), rice (Li et al., 2006), Japanese apricot (Shi et al., 2011), Xanthoceras sorbifolia (Gao et al., 2002), and Prunus armeniaca L. (Lillecrapp et al., 1999). There are three main types of female sterility: flowers with no pistil, or only an incomplete pistil; flowers with pistil but lacking normal ovules; and flowers with normal ovules but in which there is abnormal embryo growth following pollination (Li et al., 2006). For fruit crops, female sterility is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it is inversely proportional to the rate of fruit set, and it therefore seriously reduces fruit yield. On the other hand, it can help assist a plant to allocate limited resources to male and female reproductive function (Bertin, 1982).

Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) is a shrub that is native to central Asia (Holland et al., 2009), it is valued for its juicy aril sacs, which are claimed to be of benefit to human health (Lansky and Newman, 2007; Basu and Penugonda, 2008; Wang et al., 2012; Jaime et al., 2013). Two types of flowers are produced on an individual pomegranate tree: FMF and BF (Holland et al., 2009; Wetzstein et al., 2011). FMFs, which are referred as “female-sterile,” or “bell-shaped,” fail to set fruit and eventually fall from the tree. BFs, on the other hand, posses well-formed pistils and can set fruit; thus they are known as “female-fertile,” “vase-shaped” (Holland et al., 2009; Wetzstein et al., 2011). The proportion of BF correlates with fruit yield, whereas FMF assist in gene dispersal on account of their more efficient pollen production (Tanurdzic and Banks, 2004; Wetzstein et al., 2011). FMF female sterility is caused mainly by abnormal ovule development (Wetzstein et al., 2011). This is also the cause of female sterility in X. sorbifolia (Gao et al., 2002) and Prunus armeniaca L (Lillecrapp et al., 1999). However, the molecular mechanism of female sterility in fruit crops remains unknown.

In some plant species, such as Arabidopsis, cotton, and rice, significant progress in elucidating the molecular mechanism of ovule development has been achieved (Baker et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2006; Kubo et al., 2013). The ABCDE model of flower determination and development has indicated that a specific class of MADS-box genes are key regulators of ovule development (Colombo et al., 1995; Theißen and Saedler, 2001; Tsai and Chen, 2006). The investigation of agamous (AG) mutant in Arabidopsis showed a complete lack of both stamens and carpels, which indicate the importance of AG in specifying carpel identity (Bowman et al., 1991). AG is a key regulator of carpel development, through controlling the expression of other genes with regulatory functions (Ó’Maoiléidigh et al., 2013). In particular, AG subfamily genes positively regulate the expression of SPL (Ito et al., 2004). SPL regulates ovule development by repressing the expression of a number of genes that are important in ovule development, such as ANT, BEL1 and INO, but the mechanism of SPL repression of these genes remains unknown (Sieber et al., 2004; Wei et al., 2015). ANT and INO are key regulators of ovule integument formation (Grossniklaus and Schneitz, 1998). ANT is a member of (APETALA2)/EREBP (Ethylene Responsive Element Binding Protein) multi-gene family that regulates the formation of ovule integument primordium by controlling cell growth and number (Mizukami and Fischer, 2000; Shigyo et al., 2006). ANT contains two AP2 domains homologous with the DNA binding domain of ethylene response element binding proteins (EREBPs) which was most surely involved in ethylene signal transduction (Klucher et al., 1996; Cucinotta et al., 2014). Previous studies have demonstrated the roles of ethylene in regulating sex determination and increasing the number of female flowers in cucumber and orchid as well as restoring ovule development in the transformed tobacco (Iwahori et al., 1970; De Martinis and Mariani, 1999; Yamasaki et al., 2003; Papadopoulou et al., 2005; Boualem et al., 2008; Tsai et al., 2008). Consistent with ANT, AP2 also belongs to AP2 subfamily and encodes a transcription factor for putative protein which was same as ethylene responsive factor, ERF protein, that can inhibit the expression of AG gene (Pinyopich et al., 2003; Licausi et al., 2013). AG family genes are important upstream regulators of ovule development (Dreni and Kater, 2014).

The formation of pomegranate FMF has been associated with abnormal ovule development, but the stage at which ovule abortion occurs, and the causes of abortion, remain unknown. In this study, by means of morphological observations using SEM, we have identified the key developmental stage for ovule abortion. Then, through a combination of RNA sequencing and ethephon treatment, we have identified the candidate genes responsible for female sterility. Our results are important in shedding light on the mechanism of gynoecia development in pomegranate.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth and Sample Collection

Pomegranate flowers were collected from 10-year-old “Tunisiruanzi” trees grown in nursery of the Zhengzhou Fruit Research Institute located in Zhengzhou, Henan, China, and managed using conventional methods. BF and FMF were separated based on the morphology of the ovary, which in FMF is atrophied (Holland et al., 2009). The ovules of FMF cease differentiation when their BVD was 5.0–13.0 mm. A total of 18 accessions were sequenced, comprising three BF and three FMF, and including three biological replicates. To describe the accessions clearly, we used TNSI, TNSII, and TNSIII represent BF buds when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, 13.1–25.0 mm, respectively. Similarly, ATNSI, ATNSII, and ATNSIII represented the FMF buds when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, 13.1–25.0 mm, respectively. Following collection, all samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C.

RNA Extraction and Sequencing

Total RNA extraction was performed using the CTAB (Cetyltrimethyl Ammonium Bromide) method. RNA purity was checked using a NanoDrop® 2000 instrument (Thermo, Wilmington, CA, United States). RNA concentration and integrity were measured using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). Library preparation and sequencing reactions were carried out by 1Gene, Corp. (Hangzhou, China)1 according to the relevant manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States).

Library Preparation for Transcriptome Sequencing

A total amount of 5 μg RNA per sample was used as input material for the RNA sample preparations. Sequencing libraries were generated using a NEBNext® UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, Ipswich, MA, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations, and index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. Briefly, mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. Fragmentation was carried out using divalent cations under elevated temperature in NEB-Next® First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5×) (NEB, Ipswich, MA, United States). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primer and M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (RNase H-). Second-strand cDNA synthesis was subsequently performed using DNA polymerase I and RNase H. Remaining overhangs were converted into blunt ends using exonuclease/polymerase activities. Following adenylation of the 3′-ends of the DNA fragments, a NEBNext adaptor with a hairpin loop structure was ligated to prepare the fragments for hybridization. In order to select cDNA fragments of preferentially 250–300 bp in length, the library fragments were purified using an AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, MA, United States). The size-selected, adaptor-ligated cDNA was incubated with 3 μl of USER Enzyme (NEB) at 37°C for 15 min. PCR was then performed with Q5 Hot Start HiFi DNA polymerase (NEB, Ipswich, MA, United States), Universal PCR primers and Index (X) Primer. Finally, the PCR products were purified (AMPure XP system) and library quality was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system.

Clustering and Sequencing

Clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using a TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v4-cBot-HS (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform and paired-end reads were generated.

Data Analysis

Quality Control

Raw data (raw reads) in FASTQ format were firstly processed through in-house Perl scripts. In this step, clean data (clean reads) were obtained by removing reads containing adapter, reads containing poly-N and low-quality reads from raw data. At the same time, the Q20, Q30 and GC content of the cleaned data were calculated. All the downstream analyses were based on the high-quality cleaned data.

Mapping Reads to the Reference Genome

Reference genome and gene model annotation files were obtained form our lab (unpublished data). The index of the reference genome was built using Bowtie v2.2.3 and paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using TopHat v2.0.12 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012; Kim et al., 2013). We selected TopHat as the mapping tool because TopHat can generate a database of splice junctions based on the gene model annotation file and thus produces a better mapping result than other non-splice mapping tools.

Quantification of Gene Expression Level

Reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped (RPKM) of each gene was calculated based on the length of the gene and the reads count mapped to this gene. RPKM, takes account simultaneously of the effect of sequencing depth and gene length for the reads count, and is currently the most commonly used method of estimating gene expression levels (Trapnell et al., 2010).

Differential Expression Analysis

Prior to differential gene expression analysis, for each sequenced library, the read counts were adjusted using the edgeR program package with a one-scale normalizing factor. Differential expression analysis of the two groups (three biological replicates per group) was performed using the DESeq R package (1.20.0)2. DESeq provides statistical routines for determining differential expression in digital gene expression data, using a model based on the negative binomial distribution. The resulting P-values were adjusted using the Benjamin and Hochberg approach for controlling the false discovery rate (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). Genes with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 found by DESeq were assigned as differentially expressed. An adjusted P-value of 0.005 and a log2 (fold change) of 1 were set as the threshold for significantly differential expression.

Go and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of DEGs was carried out using topGO, in which gene length bias was adjusted. GO terms with a adjusted P-value < 0.05 were considered to be significantly enriched in DEGs.

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) is a database resource for understanding the high-level functionalities of a biological system – such as the cell, the organism, and the ecosystem – from molecular-level information, especially data from large-scale molecular datasets generated by genome sequencing and other high-throughput experimental technologies3. R software was used to test the statistical enrichment of DEGs in KEGG pathways.

Gene Co-expression Network Analysis

Gene co-expression network analysis was performed using the weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA) (v1.29) package in R (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008). Only genes with a RPKM value greater than 2 in all samples were analyzed. The modules were obtained using the automatic network construction function “blockwiseModules” with default settings, TOMType “signed,” minModuleSize = 30, and mergeCutHeight = 0.25. The total connectivity and intramodular connectivity (function “softConnectivity”), kME, and kME-p-value were calculated. The correlations between modules and four traits (BVD, SL, OTD, and OVD) were calculated by the “cor” function in R, with significance calculated using corPvalueStudent. The correlation between modules and samples was undertaken using module Eigengenes in WGCNA. The networks were visualized using Cytoscape _v.3.0.04.

Real-time RT-PCR Analysis

To verify the RNA-Seq analysis, we performed qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of nine genes, which included two genes (ETR, ERF1/2) related to the ethylene response and seven genes (three AG, two SPL, one ANT and one INO) related to pistil development. The actin gene was used as a reference (Supplementary Table S9). RNA was extracted as described above and cDNA was synthesized using a TIANscript RT Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). PCR was performed using 2 × SYBR Green Real-time PCR Master Mix (Roche) on a real-time PCR instrument (Roche 480, Basle, Switzerland), with the following program: pre-incubation at 95°C for 5 min, then followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 10 s. The ddCt method was used to calculate gene expression levels (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S9.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Pistil of FMF and BF were collected when their BVD were 3.0–5.0, 5.1–10.0, 10.1–13.0, 13.1–15, 15.1–18.0, 18.1–20.0, 21.1–25.0, and 25.1–35.0 mm (blooming). Samples were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (pH = 7.4) for > 1 week at 4°C. Following fixation, they were dehydrated using an ethanol series [30% ethanol, 20 min; 50% ethanol, 20 min; 70% ethanol, 20 min; 100% ethanol, 30 min (twice)]. The dehydrated samples were then dried in a critical-point drying apparatus (Quorum, England). Dried samples were mounted on stubs and sputter-coated with gold (FEI, America) and observed under a SEM (FEI Quanta 250, America) in Henan University. Ten floral buds were observed in each stage.

Morphology of Bisexual Flowers (BF) and Functional Male Flowers (FMF)

Flower buds at different stages were collected based on BVDs. Measurements of flower BVD, OTDs, SL were made using a Dsect mirror (DS-Fiec, Nikon) or by vernier caliper. Ten biological replicates were measured for each stage. Difference significance analysis between BF and FMF using independent-samples t-test, P-value represent significance of difference.

Treatment with Plant Growth Regulator

“Tunisiruanzi” pomegranate trees were sprayed with an aqueous solution of ethephon at concentrations of 150, 200, and 250 mg/L, with three biological replications per treatment. Control sprayings were with water alone. Each tree was sprayed with 1. Five liter aqueous solution of ethephon or water (control). Treatments were sprayed on whole trees once, including both floral buds and leaves at a BVD of 3.0–5.0 mm (April 22, 2016), at which stage it is not yet possible to distinguish BF from FMF.

Results

Morphology of Pomegranate Bisexual Flowers (BF) and Functional Male Flowers (FMF)

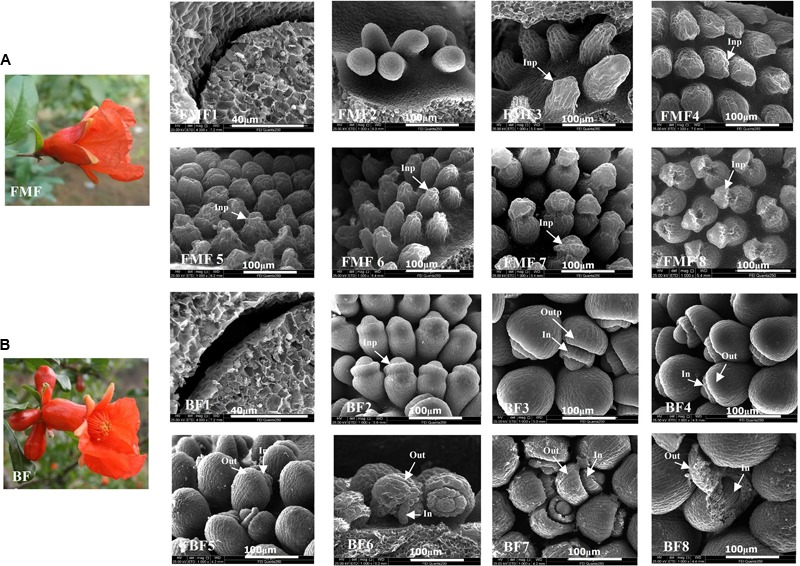

The morphology of FMF is bell-shaped, whereas that of BF is vase-shaped (Figures 1 FMF, 1BF). Pistils of FMF and BF were collected when their BVDs were: 3.0–5.0 mm (Figures 1FMF1, 1BF1); 5.1–10.0 mm (Figures 1FMF2, 1BF2); 10.1–13.0 mm (Figures 1FMF3, 1BF3); 13.1–15.0 mm (Figures 1FMF4, 1BF4); 15.1–18.0 mm (Figures 1FMF5, 1BF5); 18.1–20.0 mm (Figures 1FMF6, 1BF6); 20.1–25.0 mm (Figures 1FMF7, 1BF7) and during flowering (BVD ≥ 25.1 mm) (Figures 1FMF8, 1BF8). The dynamics of ovule development of FMF and BF were observed (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) and photographs showing the developmental stages of the functional male flowers (FMF) ovule and bisexual flowers (BF) ovule. (A) The morphologies of FMF, (B) the morphologies of BF. (FMF1–8) The ovule development of FMF when their bud vertical diameter (BVD) was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–10.0, 10.1–13.0, 13.1–15.0, 15.1–18.0, 18.1–21.0, and 21.1–25.0 mm, flowering time (BVD ≥ 25.1 mm). (BF1–8) represented the ovule development of BF when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–10.0, 10.1–13.0, 13.1–15.0, 15.1–18.0, 18.1–21.0, and 21.1–25.0 mm, flowering time (BVD > 25.1 mm).

There were no obvious differences observed between BF1 and FMF1 (BVD 3.0–5.0 mm), at this stage, the placenta had formed but no ovule primordia were observable. Stage BF2 (BVD 5.1–10.0 mm) was characterized by the formation of inner integument primordia. However, in FMF2, though the ovules were enlarged, no inner integument primordia had formed. At BF3 (BVD 10.1–13.0 mm), outer integument primordia formed, the inner integument showed an increase in the number of cell layers and became symmetrically enlarged, growing parallel to the nucellus by anticlinal division and cell elongation (Reiser and Fischer, 1993). By contrast, at FMF3 (BVD 10.1–13.0 mm), inner integument primordium formed in part of the ovules, but no inner integument extension and outer integument primordia were observed, ovules displayed wilting. Thereafter, ovules undergo wilting during stage FMF4–8. In BF, on the other hand, the integument continued to enlarge during stage BF4 (BVD 13.1–15.0 mm); and during the subsequent stages BF5–7 (BVD 15.1–25.0 mm), the outer integument exhibited a gradient of cell division, which showed maximal growth on the abaxial side and almost no growth on the adaxial side (Robinson-Beers et al., 1992). By the reason of this asymmetric growth, by stage BF8 (when the flowers were in bloom), the outer integument completely enclosed the inner integument and the nucleus. From this comparison of FMF and BF, it was apparent that early ovule development in FMF was indistinguishable from that in BF. One of the reasons for pistil abortion in FMF may be the termination of ovule development after stage FMF3 (BVD 10.1–13.0 mm).

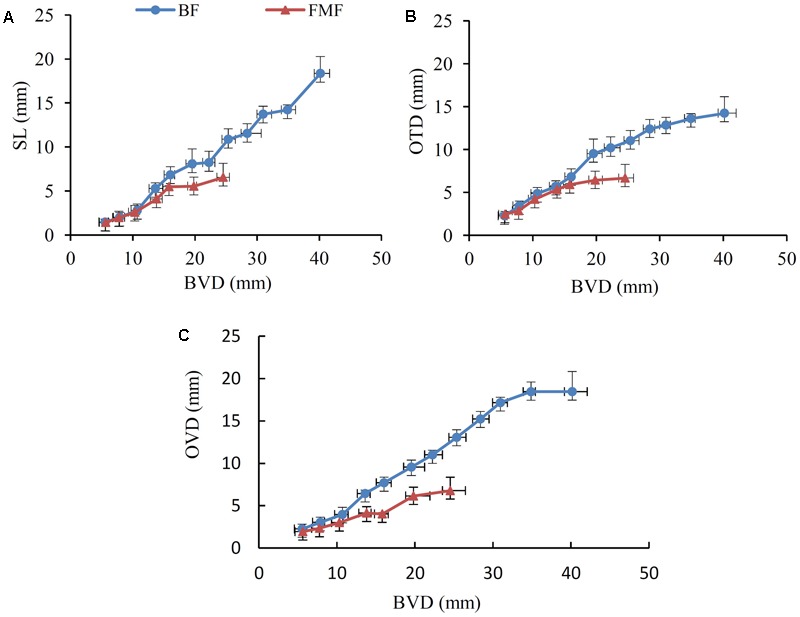

At flowering time, FMF were smaller than BF (Figure 1A). FMF bloomed at a BVD of 24.54 ± 1.59 mm (Figures 2A–C), a SL of 7.97 ± 1.0 mm (Figure 2A), an OTD of 6.67 ± 1.33 mm (Figure 2B), and an OVD of 14.22 ± 1.85 mm (Figure 2C). In contrast, BF bloomed at a BVD of 40.18 ± 2.37 mm (Figures 2A–C), a SL of 18.34 ± 1.48 mm (Figure 2A), an OTD of 14.22 ± 1.85 mm (Figure 2B), and an OVD of 14.22 ± 1.85 mm (Figure 2C). Thus, during the flowering period, the OTD (P < 0.01), the SL (P < 0.05) and the OVD (P < 0.01) were clearly shorter in FMF than in BF (Supplementary Table S1).

FIGURE 2.

Changing curve of style length (SL), ovary transverse diameter (OTD), and ovary vertical diameter (OVD) of BF and functionally male flowers of ‘Tunisiruanzi’ with BVD. (A) Changing curve of SL with BVD. (B) Changing curve of OTD with BVD. (C) Changing curve of OVD with BVD. SL, style length; OTD, ovary transverse diameter; OVD, ovary vertical diameter. Transverse error bars means standard deviation of BVD, vertical error bars means standard deviation of SL OVD and OTD. Each data point represents the mean value of 10 technical replicates.

Remarkably, in FMF, the increase in OTD, SL and OVD began to decline when BVD grow into 10.32 ± 0.77–15.82 ± 0.13 mm (Figures 2A,B), suggesting OTD, SL and OVD can be indicators for female sterility. The SEM results showed that the key stage at which ovule abortion occurred when BVD was 10.0–13.0 mm (Figure 1). The data further prove the key stage of pomegranate female sterility was 10.0–13.0 mm in BVD.

Transcriptome Sequencing of Pistils

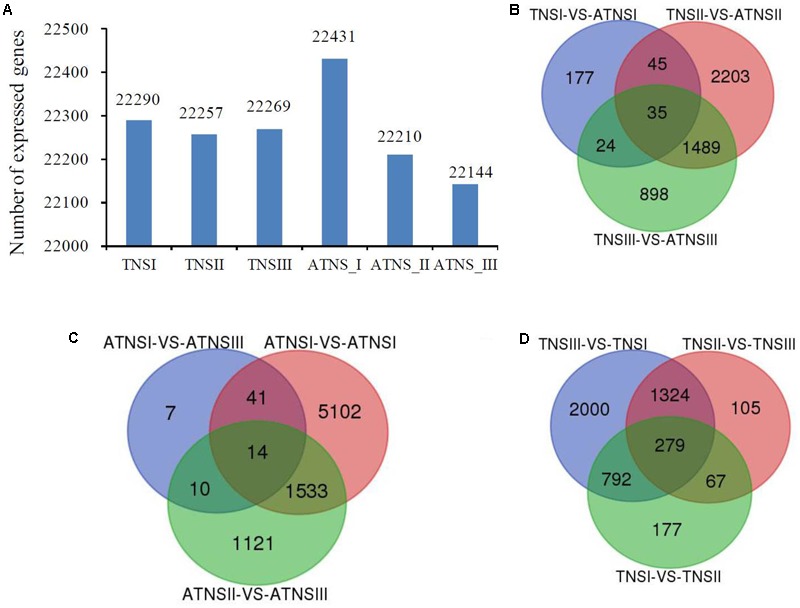

In order to denote the accessions clearly, we used TNSI, TNSII, and TNSIII represent the BF buds’ pistils when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, 13.1–25.0 mm, respectively. Similarly, the designations ATNSI, ATNSII, and ATNSIII were used to represent the FMF buds’ pistils when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, 13.1–25.0 mm, respectively. There were three replicates for each developmental stage. In total, 18 accessions were used for transcriptomic sequencing. Sequencing of 18 accessions by Illumina platform obtained a total of 841 million clean reads of sequence, with an average of 46.7 million clean reads and 92.08% of mapped rate for each accession (Supplementary Table S2). The raw data were uploaded to NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), a total of 18 samples with accession numbers SRX2735567-SRX2735584 were uploaded5. Pearson r2 correlation values for all replications were used to evaluate the consistency of the raw data. Most of them varied from 0.85 to 1.0, and data with a value <0.80 were removed prior to subsequent analysis (Supplementary Figure S1). The data showed that the sequencing quality was high enough for further analysis (Supplementary Figure S1). A total of 25,959 genes were detected, with only a small variation between accessions (Supplementary Table S2). The highest number of expressed genes was 22,431, obtained from ATNSI (Figure 3A), while the lowest number (22,144) was from ATNSIII (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table S2).

FIGURE 3.

The number of different expressed genes. (A) Different number of expressed genes in different stages. (B–D) Unique and shared DEGs among different stages for both BF and FMF. TNSI, TNSII, TNSIII represent pistil of BFs when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm, respectively. ATNSI, ATNSII, ATNSIII stand for pistil of FMFs when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm, respectively. (B) The number of DEGs between ATNSI -VS- TNSI, ATNSII -VS- TNSII, ATNSIII -VS- TNSIII. (C) The number of DEGs between ATNSI -VS- ATNSII, ATNSI -VS- ATNSIII, ATNSII -VS- ATNSIII; (D) The number of DEGs between TNSI -VS- TNSII, TNSI -VS- TNSIII, TNSII -VS- TNSIII; Venn diagrams were drawn using a online tool Venn Diagrams (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). BF, bisexual flowers; FMF, functional male flowers. VS in B–D represent versus.

Differentially Expressed Genes and Enrichment Analysis

A total of 9662 unique DEGs were obtained. Between TNSI and ATNSI, the number of DEGs was 281, whereas it was 3,772 between TNSII and ATNSII. However, the number decreased to 2,446 when comparing TNSIII with ATNSIII (Figure 3B). Moreover, a total of 7,828 DEGs were detected between the FMF different development stages (ATNSI-ATNSII, ATNSI-ATNSIII, and ATNSII-ATNSIII) and 4,744 DEGs were detected between three stages of BF development (TNSI-TNSII, TNSI-TNSIII, and TNSII-TNSIII) (Figures 3C,D). The DEGs were listed in Supplementary Table S3.

An enrichment analysis was performed to determine whether the genes (DEGs) that were differentially expressed between FMF and BF were markedly associated with specific pathways or biological processes. The DEGs were characterized using the GO and KEGG databases. The GO terms comprise three categories: molecular function, cellular component, and biological process. A total of 4,781 unique genes were enriched between FMF and BF (TNSI-ATNSI, TNSII-ATNSII, and TNSIII-ATNSIII). For the TNSI-ATNSI DEGs, the classification terms that showed enrichment included “response to hormone” (GO:0009725), “cell death” (GO:0008219), “signal transduction” (GO:0007165), “regulation of programmed cell death” (GO:0043067), “response to ethylene” (GO:0009723), “ethylene biosynthetic process” (GO:0009693), and “regulation of cellular process (GO:0050794)” (Supplementary Table S3). In contrast, for the TNSII-ATNSII DEGs, the enriched classification terms were “cell proliferation” (GO:0008283), “DNA methylation” (GO:0006306, GO:0044728), “regulation of cell cycle” (GO:0051726), “cell cycle” (GO:0007049), “mitotic cell cycle process” (GO:1903047), “G2/M transition of mitotic cell cycle” (GO:0000086), “cell division” (GO:0051301), “regulation of gene expression, epigenetic” (GO:0040029), and “nuclear division” (GO:0000280) (Supplementary Table S3). For the TNSIII-ATNSIII comparison, the enriched terms belonged to categories including “cell cycle” (GO:0007049), “cell division” (GO:0051301), “mitotic cell cycle process” (GO:1903047), “regulation of growth” (GO:0040008), “flower development” (GO:0009908), “nuclear division” (GO:0000280), “reproductive structure development” (GO:0048608), and “floral organ morphogenesis” (GO:0048444) (Supplementary Table S3). From the SEM results, ovule development of FMF ceased after the formation of the inner-integument primordium. Thus, the DEGs in the enriched categories such as “cell cycle,” “cell division,” “floral development,” and “floral organ morphogenesis” may be candidate genes associated with pistil abortion. The enrichment analysis revealed a total of 114 DEGs related to flower development (Supplementary Table S3).

Spraying with ethephon can increase the proportion of BF (Chaudhari and Desai, 1993). Consistent with this, the category “response to ethylene” (GO:0009723) was enriched between BF and FMF, consistent with the role of ethylene in pomegranate female sterility.

Pathway assignment was carried out by KEGG to analyze the biological functions of DEGs. A total of 1,302 unique DEGs between FMF and BF were mapped into KEGG pathways, containing 41, 809 and 452 DEGs between TNSI-ATNSI, TNSII-ATNSII and TNSIII-ATNSIII comparison, respectively. For the TNSI-ATNSI comparison, pathways related to “plant hormone signal transduction” (ko04075), “plant–pathogen interaction” (ko04626), and “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” (ko01110) were enriched (Supplementary Table S4). For the TNSII-ATNSII comparison, the main pathways included “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” (ko01110), “plant hormone signal transduction” (ko04075), and “metabolic pathways” (ko01100) (Supplementary Table S4). Similarly, “plant hormone signal transduction” (ko04075), “metabolic pathways” and “biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” (ko01110) were enriched in the TNSIII-ATNSIII comparison (Supplementary Table S4). The process of plant hormone signal transduction (Supplementary Figure S3) was concluded to be a putative pathway affecting pomegranate FMFs’ ovule development.

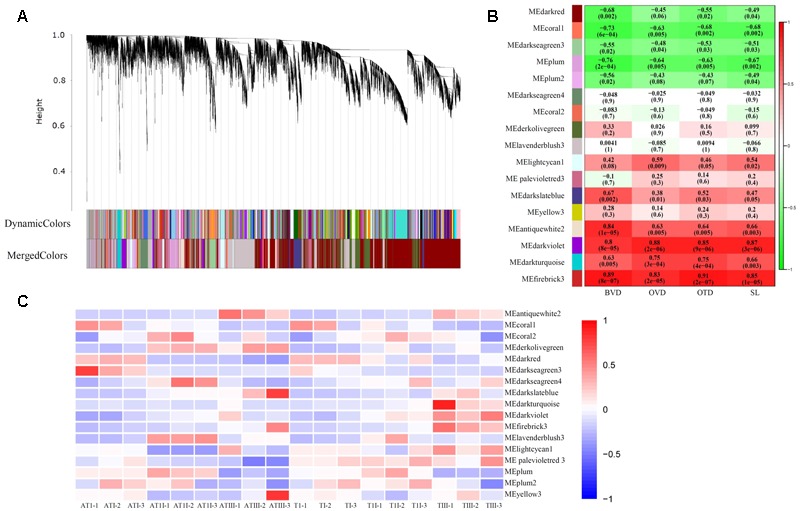

Gene Co-expression Network Analysis Using WGCNA

Constructing a dendrogram, a total of 17 distinct modules were obtained, in which each tree branch formed a module, and each leaf in the branch represented one gene (Figure 4A and Supplementary Table S5). The correlation between different modules were showed in Supplementary Figure S2. Genes in different modules were characterized by GO (Supplementary Table S6). From the measurement of the various different indices for FMF and BF, we determined differences in OTD, OVD, and SL as the growth of BVD between FMF and BF (Figure 2). The associations between these parameters and the 17 distinct modules were then compiled (Figure 4B). The modules related to SL are those named MEantiquewhite2, MEdarkviolet, MEdarkturquoise and MEfirebrick 3 (r ≥ 0.6) (Figure 4B); the same correlations were seen for OTD and OVD (Figure 4B); the modules related to BVD are those named MEdarkslateblue, MEantiquewhite2, MEdarkviolet, MEdarkturquoise and MEfirebrick 3 (r ≥ 0.6) (Figure 4B). According to the GO enrichment, “single-organism process” (GO:0065007), “organic substance metabolic process” (GO:0071704), “biological regulation” (GO:0065007), “organic substance biosynthetic process” (GO:0044711), “small molecule metabolic process” (GO:0044281), “phosphate-containing compound metabolic process” (GO:0006796), “lipid metabolic process” (GO:0006629), “lipid biosynthetic process” (GO:0008610) and “organonitrogen compound metabolic process” (GO:1901564) were also enriched in these modules (Supplementary Table S6). Genes related to flower development were revealed by the association between modules and tissues (Figure 4C). Gene modules showing differential expression between FMF and BF are named MElavenderblush 3, MElightcyan1, MEdarkred, MEdarkolivegreen, and MEpalevioletred 3 (Figure 4C). These modules were enriched mainly in the categories “cellular process” (GO:0009987), “single-organism process” (GO:0044699), and “metabolic process” (GO:0008152). Processes associated with flower development were also enriched (GO:0048573, GO:0009911, GO:0010227, GO:0048573, GO:0009911, GO:0009908, GO:0009909, GO:0048574) (Supplementary Table S6). A total of 20 genes related to flower development were enriched by the module-tissues association (Supplementary Figure S4 and Table S7). Analysis of the association between modules and tissues revealed enrichment of 20 genes related to flower development (Supplementary Figure S3 and Table S7).

FIGURE 4.

Genes co-expression network analysis with WGCNA. (A) Hierarchical cluster tree of different co-expression modules. Each branch constitute one module, and each leaf in the branches represented one gene. A total of 17 distinct modules were labeled by different colors. (B) Module-trait association. Each row corresponds to a module. Each column amount to a trait. BVD, bud vertical diameter; OTD, ovary transverse diameter; OVD, ovary vertical diameter; SL, style length. The color at the right represented the size of correlation coefficient, the digital labels in the box in B stand for correlation coefficient (r) (upside) and test value (P-value) (bottom). Those modules with r > 0.6, P-value < 0.05 were selected to discuss. (C) Module-tissue association. Each row corresponds to a module. Each column amount to a tissue. The color of each box at the row/column intersection showed the size of correlation coefficient between the module and the tissue type. ATI, ATII, ATIII represented pistil of FMF when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm. TI, TII, TIII represented pistil of BF when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm.

Genes Related to Ovule Development

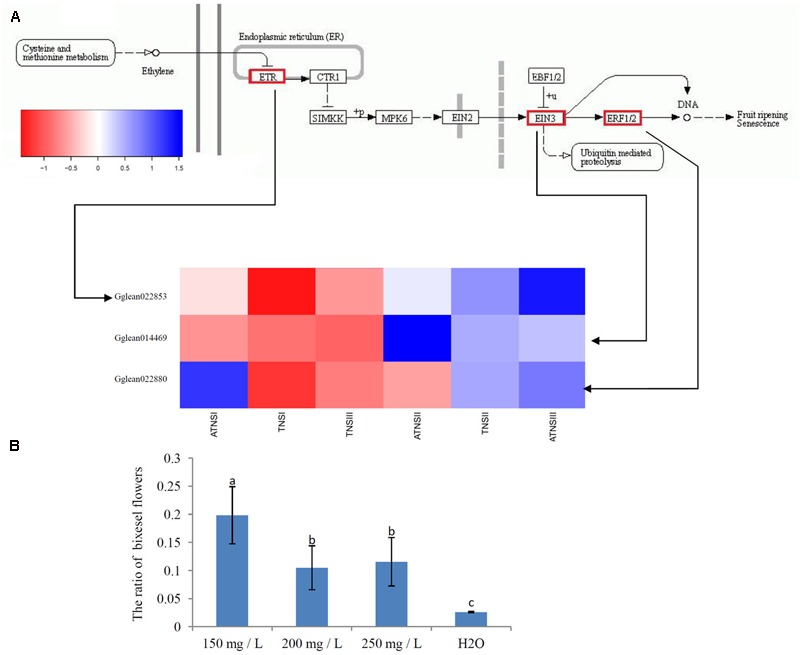

Abnormal ovule development was the main factor responsible for the abortion of pomegranate flowers. Ovule development comprises several processes: primordia initiation, specification of identity, pattern formation, and eventually morphogenesis and cellular differentiation (Grossniklaus and Schneitz, 1998). The pathway of regulation of Arabidopsis ovule development was showed in Figure 5, and key regulators include AGAMOUS (Yanofsky et al., 1990; Drews et al., 1991), SPL (Ito et al., 2004), INO (L’eon-Kloosterziel et al., 1994), ANT and BEL1 (Brown et al., 2010). A total of ten AGAMOUS-like DEGs (Gglean016200, Gglean018861, Gglean020089, Gglean026618, Gglean028014, Gglean028632, Gglean030294, Gglean002838, Gglean006764, and Gglean022339), five SPL homolog genes (Gglean016197, Gglean022102, Gglean028488, Gglean001912, and Gglean005812), two ANT homolog genes (Gglean003340 and Gglean011480), two BEL1 homolog genes (Gglean014222 and Gglean001981), and one INO homolog gene (Gglean016270) involved in ovule development were differential expressed between BF and FMF (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S8). In the TNSII-ATNSII comparison, which was the key stage for pistil abortion in pomegranate FMF, three AG-like genes (Gglean026618, Gglean028632, and Gglean028014), one SPL homolog gene (Gglean005812), two ANT homolog genes (Gglean003340 and Gglean011480), and one INO homolog gene (Gglean016270) showed significantly different expression levels (Supplementary Table S8). The results indicated that these genes may be the main regulators for the formation of FMF.

FIGURE 5.

Expression of candidate genes involved in ovule development. Gene expression was measured by log2Ratio. ATNSI, ATNSII, ATNSIII represented pistil of FMF when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm. TNSI, TNSII, TNSIII represented pistil of BF when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm. Gene ID highlighted in red represent DEGs in ATNSII-TNSII comparison. Different colors from blue to red showed the relative log2 (expression ratio).

Identification of Genes Involved in Ethylene Signal Transduction

We identified three DEGs involved in the ethylene signal transduction process: ETR (Gglean022853), EIN3 (Gglean14469), and ERF1/2 (Gglean022880) (Figure 6A and Supplementary Table S8). To verify the role of ethylene in FMF, we sprayed ethephon at the stage of TNSI (ATNSI) with different concentration. We found that at all concentrations used ethephon had a significant effect on the proportion of BF. With water sprayed as a control, the proportion of BF was 2.2 ± 0.00%. At 150 mg/L of ethephon, the proportion of BF was increased to 19.83 ± 0.51%, whereas at 200 and 250 mg/L ethephon the proportion was 11.5 ± 0.43 and 10.5 ± 0.39%, respectively. The results indicated that 150 mg/L was the optimal concentration for improving the proportion of BF in pomegranate (Supplementary Table S8). The findings using ethephon were consistent with the transcriptomics results indicating that DEGs related to ethylene response may be associated with pistil abortion in FMF (Figure 6B). Ethylene may act as an upstream factor for pomegranate FMF female sterility.

FIGURE 6.

Expression of candidate genes involved in ovule development. (A) Expression of candidate genes involved in ethylene signal transduction. Gene expression was measured by log2Ratio. ATNSI, ATNSII, ATNSIII represented pistil of FMF when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm. TNSI, TNSII, TNSIII represented pistil of BF when their BVD was 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm. Different colors from blue to red showed the size of correlation coefficient. (B) Effects of different concentrations of ethylene on the ratio of BF. mg/L stands for the concentrations of ethylene. Control sprayed by water. Different small letters indicate significant difference between treatments at P < 0.05 by Duncan’s new multiple range test. Error bar represented standard deviation.

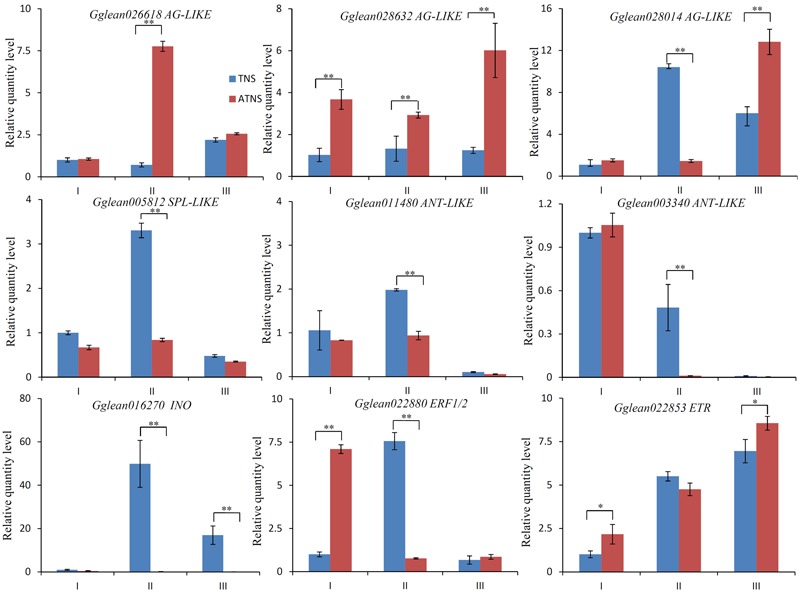

qRT-PCR Analysis of Selected DEGs

To confirm the results of RNA sequencing, seven DEGs related to ovule development including three AGAMOUS-like DEGs (Gglean026618, Gglean028632, and Gglean028014), one SPL homolog gene (Gglean005812), two ANT homolog genes (Gglean003340 and Gglean011480) and one INO homolog gene (Gglean016270) were selected for qRT-PCR analysis. In addition, two DEGs associated with ethylene signal transduction, ETR (Gglean022853) and ERF1/2 (Gglean022880), were also analyzed between BF and FMF at three stages during flower development (Figure 7). The results showed a similar expression trend to the transcriptome analysis. Three AGAMOUS-like homologous genes showed differing expression patterns. Gglean026618 was up-regulated in ATNSII in the ATNSII-TNSII comparison, and Gglean028632 displayed up-regulated in FMF in the comparisons ATNSI-TNSI, ATNSII-TNSII, and ATNSIII-TNSIII. In contrast, Gglean028014 was down-regulated in ATNSII relative to TNSII. Similarly, the SPL homolog gene Gglean005812 was down-regulated in ATNSII relative to TNSII. Two ANT homolog genes (Gglean003340 and Gglean011480) was down-regulated in ATNSII relative to TNSII and almost no expression in TNSIII and ATNSIII. The INO homolog gene (Gglean016270) displayed almost the same trend as the ANT homologs. ETR (Gglean022853), the repressor of ethylene signal transduction, was up-regulated in ATNSI relative to TNSI and ATNSIII relative to TNSIII. ERF1/2 (Gglean022880), the downstream gene in ethylene signal transduction pathway, displayed differential expression in both the ATNSI-TNSI and ATNSII-TNSII comparisons, being up-regulated in ATNSI relative to TNSI but down-regulated in ATNSII relative to TNSII.

FIGURE 7.

Relative quantity level of 9 selected genes at different stages of floral buds development in BF and FMF. Stage I, II, and III represents pistils of flower buds when their BVD were 3.0–5.0, 5.1–13.0, and 13.1–25.0 mm, blue column represents BF, red column represents FMF. Relative quantity levels were calculated by 2-ΔΔCT method with actin as a standard. ∗Represents the level of significance difference P < 0.05, ∗∗ represents the level of significance difference P < 0.01 in independent-samples t-test.

Discussion

Nutrient Metabolism May Effect Pomegranate Female Sterility

Here, we set out to explore candidate genes associated with pistil abortion in pomegranate FMF. The key stage for pistil abortion in FMF was found to be at a BVD of 5.0–13.0 mm, when the development of the ovule ceased following the formation of the inner integument primordium. Pistil abortion is widespread in a series of fruit crops, including Japanese apricot, X. sorbifolia, and Prunus armeniaca L. (Lillecrapp et al., 1999; Gao et al., 2002; Shi et al., 2011). Although the morphological characteristics of pistil abortion are distinct between species, all instances of pistil abortion result from the abnormal development of ovules. Pomegranate FMF display termination of ovule development after the formation of the inner integument primordium, and this may be the main reason for pistil abortion in this species. In addition, in Japanese apricot it has been reported that pistil abortion may be associated with the catabolism of macromolecular nutrients in the flower buds (Shi et al., 2011). Based on module-trait co-expression analysis (Figure 4B), some processes related to macromolecular nutrients, including “organic substance biosynthetic process” (GO:0044711), “small molecule metabolic process” (GO:0044281), and “organ nitrogen compound metabolic process” (GO:1901564), were found to be overrepresented, suggesting that the abortion of pomegranate FMF may be related to the catabolism of nutrients (Figure 4B).

Key Regulatory Factors of Ovule Development May Be Associated with Pomegranate Female Sterility

A comparative transcriptomic analysis between BF and FMF in different developmental stages was then undertaken to mine candidate genes. Significant progress in understanding the molecular mechanism of ovule development has been achieved in some species, such as Arabidopsis, cotton, and rice (Baker et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2006; Kubo et al., 2013). AG, SPL, ANT, BEL1 and INO have been found to be key regulators of ovule development (Ito et al., 2004; Sieber et al., 2004; Ó’Maoiléidigh et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2015). In the present study, seven DEGs related to ovule development, expressed differentially at the key stage of FMF pistil abortion, have been verified by means of qRT-PCR, including three AG homolog genes, one SPL homolog, two ANT homologs and one INO homolog. Previous studies have indicated that ANT and INO are key regulators of the formation of the ovule integument (Grossniklaus and Schneitz, 1998), and here both showed down-regulation in ATNSII relative to TNSII. Furthermore, the morphology of the ovules of pomegranate FMF was similar to that of Arabidopsis ant-72F5 ovules (Grossniklaus and Schneitz, 1998). Collectively, our results indicated that ANT may be a key regulator gene of pistil abortion in pomegranate FMF. SPL can promote the growth of ovule integuments (Balasubramanian and Schneitz, 2002). SPL was down-regulation in the key stage of pistil abortion (ATNSII-TNSII) in FMF, which indicated the role of SPL promoting pomegranate ovule development. Previous studies indicated SPL represses the expression of ANT and INO to control ovule development (Wei et al., 2015). However, in the present study, SPL, ANT and INO were down-regulated in ATNSII relative to TNSII, the possible explanation is that ANT and INO may be repressed by other upstream factors for pomegranate ovule abortion.

As important regulatory genes in flower development, AG homologs play important roles in the formation of the pistil and stamen (Bowman et al., 1991). In this study, we detected three AG homolog genes amongst the DEGs, of which two were up-regulated (Gglean026618 and Gglean028632) and one was down-regulated (Gglean028014) in ATNSII relative to TNSII. The two up-regulated genes in ATNSII were AGL19 homology gene (Gglean026618) and AGL8 homology gene (Gglean028632). Both of these two genes play important roles in floral transition (Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2000). AGL8 promotes reproductive transition through interaction with SVP and SOC1 factors (Balanzà et al., 2014). Similarly, AGL19 acts as a floral activator in FLC-independent vernalization pathway (Schönrock et al., 2006). Here we found the differential expression of these two genes between BF and FMF, suggesting AGL19 and AGL8 also play important roles in regulation of female sterility in pomegranate. The down-regulated AG gene was the homolog gene of AGL62, which can stimulate nucellus degeneration (Bertoni, 2016). Moreover, AGL62 homology gene Gglean028014 was up-regulated in ATNSIII relative to TNSIII. In this study, we observed ovule degradation in ATNSIII (Figure 1), suggesting that the up-regulation of AGL62 may underlie the female sterility by contributing to the degradation of ovule.

Ethylene May Act as an Upstream Factor for Pomegranate Female Sterility

Ethylene has been verified as an upstream factor for ovule development in tobacco (De Martinis and Mariani, 1999). In this study, ethylene response signal factor including ETR and ERF 1/2 displayed differential expression between BF and FMF. ETR protein acts as a repressor for the transmission of ethylene signal (Hua and Meyerowitz, 1998). ETR (Gglean022853) was up-regulated in ATNSI relative to TNSI indicated the suppression of ethylene signal transduction may be a factor influencing pomegranate ovule development. Down-regulation of ERF1/2 (Gglean022880) in ATNSII relative to TNSII also supported this point. Moreover, the increase of the ratio of BF in pomegranate with external ethephon treatment further confirmed the function of ethylene in pomegranate. Jointly, our findings indicated that ethylene may act as one of the upstream regulators influencing the development of pomegranate ovule. Furthermore, ANT contains two AP2 domains homologous with the DNA binding domain of EREBPs (Shigyo et al., 2006), The down-regulation of ANT may be related to ethylene.

Collectively, we indicated that ANT homolog gene (Gglean003340, Gglean011480) and INO homolog gene (Gglean016270) may act as the downstream genes that lead to ovule abortion for pomegranate FMF. AG-Like and SPL homology genes may be upstream genes impact ANT and INO expression, but there may also exist other upstream genes repressing the expression of ANT and INO in pomegranate ovule abortion. Moreover, ethylene and nutrient may be the upstream regulators that regulated some genes related to ovule development, and the optimal spraying concentration of ethephon was 150 mg / L, which can be referenced for improving the yield of pomegranate.

Author Contributions

SC and LC conceived the project and its components. JN, HX, and LC contributed to the acquisition of materials. BL and LC accomplished the observation of embryo. LC, FZ, DZ, and QW performed spraying of ethephon and counted up the ratio of bisexual flowers. JZ, XL, and LC conducted gene expression analysis. LC and HL performed qRT-PCR, LC wrote the paper. JZ and HL helped the article proofread.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Key Project of the National Science and Technology Basic Work of China (2012FY110100), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-2015-ZFRI).

Abbreviations

- ATNS

pistil of FMF

- BF

bisexual flowers

- BVD

bud vertical diameter

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- FMF

functional male flowers

- GO

gene ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- OTD

ovary transverse diameter

- OVD

ovary vertical diameter

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- SL

style length

- TNS

pistil of BF

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.01430/full#supplementary-material

Statistics of pomegranate morphological index.

Statistics of RNA-seq, normalized total gene read counts and expressed genes number and lists.

Number of differentially expressed gene (DEG) obtained, lists of DEG, Gene Ontology enrichment of each comparison.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway of the comparison of three stages between ATNS and TNS.

Modules of gene co-expression analysis.

Gene Ontology enrichment of each gene module.

Differentially expressed genes related to flower development which enriched by gene co-expression analysis.

Differentially expressed genes related to ovule development and ethylene signal transduction.

Primers of qRT-PCR.

References

- Alvarez-Buylla E. R., Liljegren S. J., Pelaz S. (2000). MADS-box gene evolution beyond flowers: expression in pollen, endosperm, guard cells, roots and trichomes. Plant J. 24 457–466. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2000.00891.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. C., Robinson-Beers K., Villanueva J. M., Gaiser J. C., Gasser C. S. (1997). Interactions among genes regulating ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 145 1109–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balanzà V., Martínez-Fernández I., Ferrándiz C. (2014). Sequential action of FRUITFULL as a modulator of the activity of the floral regulators SVP and SOC1. J. Exp. Bot. 65 1193–1203. 10.1093/jxb/ert482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S., Schneitz K. (2002). NOZZLE links proximal-distal and adaxial-abaxial pattern formation during ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 129 4291–4300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A., Penugonda K. (2008). Pomegranate juice: a heart healthy fruit juice. Nutr. Rev. 67 49–56. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00133.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 57 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bertin R. I. (1982). The evolution and maintenance of andromonoecy. Evol. Theor. 6 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni G. (2016). What the nucellus can tell us. Plant Cell 28:1234 10.1105/tpc.16.00433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boualem A., Fergany M., Fernandez R., Troadec C., Martin A., Morin H. (2008). A conserved mutation in an ethylene biosynthesis enzyme leads to andromonoecy in melons. Science 321 836–838. 10.1126/science.1159023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. L., Smyth D. R., Meyerowitz E. M. (1991). Genetic interactions among floral homeotic genes of Arabidopsis. Development 112 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. H., Nickrent D. L., Gasser C. S. (2010). Expression of ovule and integument-associated genes in reduced ovules of Santalales. Evol. Dev. 12 231–240. 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2010.00407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari S. M., Desai U. T. (1993). Effects of plant growth regulators on flower sex in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 63 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo L., Franken J., Koetje E., Went J. V., Dons H. J., Angenent G. C. (1995). The petunia MADS-box gene FBP11 determines ovule identity. Plant Cell 7 1859–1868. 10.1105/tpc.7.11.1859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta M., Colombo L., Roig-Villanova I. (2014). Ovule development, a new model for lateral organ formation. Front. Plant Sci. 5:117 10.3389/fpls.2014.00117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Martinis D., Mariani C. (1999). Silencing gene expression of the ethylene-forming enzyme results in a reversible inhibition of ovule development in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Cell 11 1061–1071. 10.1105/tpc.11.6.1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreni L., Kater M. M. (2014). MADS reloaded: evolution of the AGAMOUS subfamily genes. New Phytol. 201 717–732. 10.1111/nph.12555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews G. N., Bowman J. L., Meyerowitz E. M. (1991). Negative regulation of the Arabidopsis homeotic gene AGAMOUS by the APETALA2 product. Cell 65 991–1002. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90551-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S. M., Ma K., Du X. H., Li F. L. (2002). Advances in research on Xanthoceras sorbifolia. Chin. Bull. Bot. 19 296–301. [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus U., Schneitz K. (1998). The molecular and genetic basis of ovule and megagametophyte development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 9 227–238. 10.1006/scdb.1997.0214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland D., Hatib K., Bar-Yaakov I. (2009). Pomegranate: botany, horticulture, breeding. Hortic. Rev. 35 127–191. 10.1002/9780470593776.ch2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honma S., Phatak S. C. (1964). A female-sterile mutant in the tomato. J. Hered. 55 143–145. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J., Meyerowitz E. M. (1998). Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 94 261–271. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81425-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Wellmer F., Yu H., Das P., Ito N., Alves-Ferreira M. (2004). The homeotic protein AGAMOUS controls microsporogenesis by regulation of SPOROCYTELESS. Nature 430 356–360. 10.1038/nature02733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahori S., Lyons J. M., Smith O. E. (1970). Sex expression in cucumber plants as affected by 2-chloroethylphosphonic acid, ethylene, and growth regulators. Plant Physiol. 46 412–415. 10.1104/pp.46.3.412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaime A., Silva T. D., Rana T. S., Narzary D., Verma N., Meshram D. T., et al. (2013). Pomegranate biology and biotechnology: a review. Sci. Hortic. 160 85–107. 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.05.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., Salzberg S. L. (2013). TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14:R36 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klucher K. M., Chow H., Reiser L., Leonore R., Robert F. (1996). The AINTEGUMENTA gene of Arabidopsis required for ovule and female gametophyte development is related to the floral homeotic gene APETALA2. Plant Cell 8 137–153. 10.1105/tpc.8.2.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo T., Fujita M., Takahashi H., Nakazono M., Tsutsumi N., Kurata N. (2013). Transcriptome analysis of developing ovules in rice isolated by laser microdissection. Plant Cell Physiol. 54 750–765. 10.1093/pcp/pct029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P., Horvath S. (2008). WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9:559 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansky E. P., Newman R. A. (2007). Punica granatum (pomegranate) and its potential for prevention and treatment of inflammation and cancer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 109 177–206. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. J., Hassan O. S. S., Gao W., Kohel R. J., Wei N. E., Kohel R. J. (2006). Developmental and gene expression analyses of a cotton naked seed mutant. Planta 223 418–432. 10.1007/s00425-005-0098-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. C., Yang L., Deng Q. M., Wang S. Q., Wu F. Q., Li P. (2006). Phenotypic characterization of a female sterile mutant in rice. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 48 307–314. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2006.00228.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Licausi F., Ohme-Takagi M., Perata P. (2013). APETALA2/Ethylene responsive factor (AP2/ERF) transcription factors: mediators of stress responses and developmental programs. New Phytol. 199 639–649. 10.1111/nph.12291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillecrapp A. M., Wallwork M. A., Sedgley M. (1999). Female and male sterility cause low fruit set in a clone of the ‘Trevatt’ variety of apricot (Prunus armeniaca). Sci. Hortic. 82 255–263. 10.1016/S0304-4238(99)00061-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’eon-Kloosterziel K. M., Keijzer C. J., Koornneef M. (1994). A seed shape mutant of Arabidopsis that is affected in integument development. Plant Cell 6 385–392. 10.1105/tpc.6.3.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami Y., Fischer L. R. (2000). Plant organ size control: AINTEGUMENTA regulates growth and cell numbers during organogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 942–947. 10.1073/pnas.97.2.942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ó’Maoiléidigh D. S., Wuest S. E., Rae L., Kwaśniewska K., Das P., Lohan A. J., et al. (2013). Control of reproductive floral organ identity specification in Arabidopsis by the C function regulator AGAMOUS. Plant Cell 25 2482–2503. 10.1105/tpc.113.113209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou E., Little H. A., Hammar S. A., Grumet R. (2005). Effect of modified endogenous ethylene production on sex expression, bisexual flower development and fruit production in melon (Cucumis melo L.). Sex. Plant Reprod. 18 131–142. 10.1007/s00497-005-0006-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinyopich A., Ditta G. S., Savidge B., Liljegren S. J., Baumann E., Wisman E. (2003). Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature 424 85–88. 10.1038/nature01741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser L., Fischer R. L. (1993). The ovule and the embryo sac. Plant Cell 5 1291–1301. 10.1105/tpc.5.10.1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Beers K., Pruitt R. E., Gasser C. S. (1992). Ovule development in wild-type Arabidopsis and two female-sterile mutants. Plant Cell 4 1237–1249. 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönrock N., Bouveret R., Leroy O., Borghi L., Köhler C., Gruissem W., et al. (2006). Polycomb-group proteins repress the floral activator AGL19 in the FLC-independent vernalization pathway. Genes Dev. 20 1667–1678. 10.1101/gad.377206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi T., Zhang Q. L., Gao Z. H., Zhang Z., Zhuang W. B. (2011). Analyses on pistil differentiation process and related biochemical indexes of two cultivars of Prunus mume. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 20 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shigyo M., Hasebe M., Ito M. (2006). Molecular evolution of the AP2 subfamily. Gene 366 256–265. 10.1016/j.gene.2005.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber P., Petrascheck M., Barberis A., Schneitz K. (2004). Organ polarity in Arabidopsis. NOZZLE physically interacts with members of the YABBY family. Plant Physiol. 135 2172–2185. 10.1104/pp.104.040154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanurdzic M., Banks J. A. (2004). Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants. Plant Cell 16 S61–S71. 10.1105/tpc.016667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theißen G., Saedler H. (2001). Plant biology: floral quartets. Nature 409 469–471. 10.1038/35054172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Williams B. A., Pertea G., Mortazavi A., Kwan G., Baren M., et al. (2010). Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28 511–515. 10.1038/nbt.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai W. C., Chen H. H. (2006). The orchid MADS-box genes controlling floral morphogenesis. Sci. World J. 6 1933–1944. 10.1100/tsw.2006.321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai W. C., Hsiao Y. Y., Pan Z. J., Kuoh C. S., Chen W. H., Chen H. W. (2008). The role of ethylene in orchid ovule development. Plant Sci. 175 98–105. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.02.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Ho J., Glackin C., Martin-Green M. (2012). Specific pomegranate juice components as potential inhibitors of prostate cancer metastasis. Transl. Oncol. 5 344–355. 10.1593/tlo.12190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B., Zhang J., Pang C., Yu H., Guo D. S., Chen Z. Y. (2015). The molecular mechanism of SPOROCYTELESS/NOZZLE in controlling Arabidopsis ovule development. Cell Res. 25 121–134. 10.1038/cr.2014.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzstein H. Y., Ravid N., Wilkins E., Martinelli A. P. (2011). A morphological and histological characterization of bisexual and male flower types in pomegranate. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 136 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S., Fujii N., Takahashi H. (2003). Characterization of ethylene effects on sex determination in cucumber plants. Sex. Plant Reprod. 16 103–111. 10.1007/s00497-003-0183-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yanofsky M. F., Ma H., Bowman J. L., Drews G. N., Feldmann K. A., Meyerowitz E. M. (1990). The protein encoded by the Arabidopsis homeotic gene agamous resembles transcription factors. Nature 346 35–39. 10.1038/346035a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Statistics of pomegranate morphological index.

Statistics of RNA-seq, normalized total gene read counts and expressed genes number and lists.

Number of differentially expressed gene (DEG) obtained, lists of DEG, Gene Ontology enrichment of each comparison.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway of the comparison of three stages between ATNS and TNS.

Modules of gene co-expression analysis.

Gene Ontology enrichment of each gene module.

Differentially expressed genes related to flower development which enriched by gene co-expression analysis.

Differentially expressed genes related to ovule development and ethylene signal transduction.

Primers of qRT-PCR.