Abstract

Although catalytic mechanisms in natural enzymes are well understood, achieving the diverse palette of reaction chemistries in re-engineered native proteins has proved challenging. Wholesale modification of natural enzymes is potentially compromised by their intrinsic complexity, which often obscures the underlying principles governing biocatalytic efficiency. The maquette approach can circumvent this complexity by combining a robust de novo designed chassis with a design process that avoids atomistic mimicry of natural proteins. Here, we apply this method to the construction of a highly efficient, promiscuous, and thermostable artificial enzyme that catalyzes a diverse array of substrate oxidations coupled to the reduction of H2O2. The maquette exhibits kinetics that match and even surpass those of certain natural peroxidases, retains its activity at elevated temperature and in the presence of organic solvents, and provides a simple platform for interrogating catalytic intermediates common to natural heme-containing enzymes.

Catalytic mechanisms of enzymes are well understood, but achieving diverse reaction chemistries in re-engineered proteins can be difficult. Here the authors show a highly efficient and thermostable artificial enzyme that catalyzes a diverse array of substrate oxidations coupled to the reduction of H2O2.

Introduction

Tailor-made protein catalysts that are compatible with the natural biomolecular components of living cells are key to realizing the ambitious goals of synthetic biology and to the provision of cheap, green catalysts for industrial biotechnology1–3. While there have been notable successes in designing de novo enzymes from engineered natural protein scaffolds4–6, the inherent complexity of evolved proteins is not a prerequisite for sustaining sophisticated functions supporting enzymatic catalysis and may even hinder the acquisition and honing of enzymatic function in such proteins1–3. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that simple, manmade proteins can reproduce selected functions and catalytic activities of natural metalloenzymes7–10. Maquettes—simple 4-α-helix bundles designed from first principles3—in particular provide a blank canvas for tractable and iterative design processes, as demonstrated by the successful incorporation of sophisticated functions common to oxidoreductases such as oxygen binding11 and intermolecular electron transfer3. However, no enzymatic activity has yet been integrated into a maquette. We recently demonstrated that maquettes can be recognized by, and processed through, the post-translational cytochrome c maturation machinery in the periplasmic space of E. coli to covalently graft heme onto the maquette backbone12, 13. These c-type cytochrome maquettes (CTMs) retain the functional legacy of their maquette precursors (e.g., oxygen binding), while providing a robust, functional framework for further oxidoreductase engineering. That the CTMs are fully and functionally assembled in vivo affords an opportunity to examine de novo protein function within living cells and facilitates the use of directed evolution strategies to improve incipient function.

Here, we demonstrate the power of the maquette approach and the utility of the CTMs through the construction of a catalytically proficient de novo enzyme. Our strategy is based on a simple, two-step conversion of a non-catalytic, CTM to produce a catalytically active holoprotein from E. coli. Remarkably, this elementary design process yields a de novo enzyme that exhibits steady-state kinetics for oxidation and oxidative dehalogenation that match and even surpass those of natural peroxidases, while providing a thermostable and chemically resistant chassis for biocatalysis.

Results

C45 design and biophysical characterization

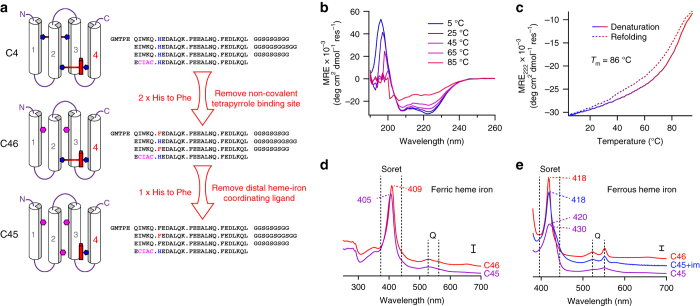

To expand the functional repertoire of our maquettes, we selected coupled substrate oxidation/H2O2 reduction for inclusion into a CTM. The natural heme-containing peroxidases that catalyze this chemistry typically contain heme B or C axially coordinated by a single histidine side chain14. We hypothesized that catalytic turnover of hydrogen peroxide within a maquette scaffold could be achieved by the construction of a monohistidine-ligated CTM from an existing CTM scaffold. To this end, we first selected a CTM with heme covalently appended to helix 4 (C4) owing to its increased thermal stability over the original parent design13. To restrict conformational flexibility and improve hydrophobic core packing, we replaced both histidines of the second, non-covalent tetrapyrrole-binding site with phenylalanine (C46) (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1A, C, E, G), removing the capacity to bind a second tetrapyrrole and increasing the melting transition temperature (T m) by 31 to 84 °C (Supplementary Fig. 2). Subsequent replacement of the distal histidine on helix 2 with phenylalanine yielded the monohistidine-ligated CTM C45; a predominantly helical protein that retains the hyperthermophilic characteristics of its precursor (T m(C45) = 86 °C) and reversibly refolds following thermal denaturation (Fig. 1b, c; Supplementary Fig. 1B, D, F, H).

Fig. 1.

Design and characterization of an artificial peroxidase. a The design process begins with C4, a CTM containing a bis-histidine heme C-binding site with the consensus motif for covalent heme incorporation on helix 4 with the distal histidine heme ligand on helix 2, and a second non-covalent tetrapyrrole-binding site (occluded by helix 2) consisting of a bis-histidine pair on helices 1 and 3. Mutation of both histidines of the non-covalent-binding site to phenylalanine produces the CTM, C46. Subsequent mutation of the distal heme C-ligating histidine ligand results in the mono-histidine ligated C45. Purification data are displayed in Supplementary Fig. 1. b Far-UV circular dichroism spectra of C45 with varying temperature collected in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58. c Temperature dependence of the CD signal monitored at 222 nm during denaturation (solid line) and refolding (dashed line). d, e UV/visible spectra of ferric (d) and ferrous (e) C45 (purple) and C46 (red). The spectrum of ferrous C45 with added exogenous imidazole is displayed in blue. Scale bars represent optical densities of 0.1

C45 exhibits ferric and ferrous UV/visible spectra (Fig. 1d, e) similar to those of the monohistidine-ligated cytochrome c′15 and horse heart cytochrome c distal methionine mutants16, suggesting either a quantum mechanical admixture of low-spin and high-spin states exists at the heme iron17 or a titratable water molecule occupies the vacant axial coordination site18, 19. The ferric C45 spectrum is pH dependent (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B), yielding a pK a of 8.11 for the transition between spectra at neutral and alkaline pH (pH 6.5–11), similar to the acid-alkaline transition pK a of horse heart myoglobin (pK a = 8.9)18 and indicative of a heme C-bound water molecule occupying the available axial heme ligation site. C45 displays a marked pH-dependence in its heme redox potential (Supplementary Fig. 3C–E), increasing from −208 mV at pH 10 to −174 mV at pH 8.6. At pH 7.5 two redox potentials are observed, likely reflecting a mixture of spin states and the water/hydroxide equilibrium at the distal coordination site. The exogenous diatomic ligand-binding function of its CTM precursors12, 13 is retained in C45: it readily binds carbon monoxide and oxygen in the ferrous form, and cyanide in the ferric form (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B). The ability to bind oxygen is strongly indicative of the retention, from previous designs, of a relatively dry and conformationally stable oxygen-binding site on the distal heme face11, 12. O2 binds 10-fold more rapidly to C45 than the bis-histidine ligated C413 (Supplementary Fig. 4C, D). Imidazole readily binds to either ferric or ferrous C45, reproducing the spectra of the six-coordinate C46 and C4 CTMs (Fig. 1d, e).

Steady-state kinetics and substrate promiscuity of C45

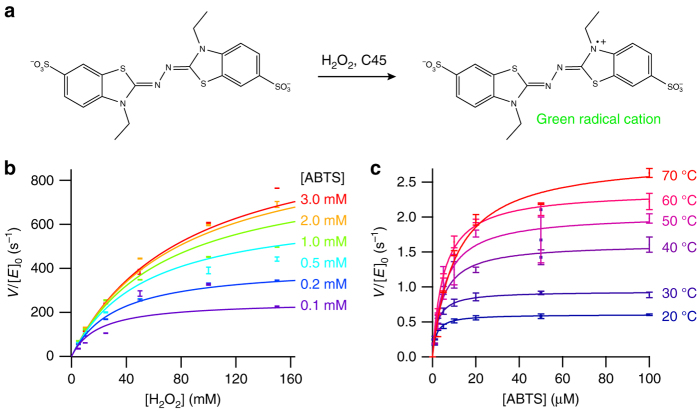

When rapidly mixed with hydrogen peroxide and the classical peroxidase substrate ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid))14, C46 very slowly bleaches indicating heme degradation with no evidence of spectroscopically isolable intermediates and little oxidized ABTS product. In contrast, when rapidly mixed with hydrogen peroxide, the monohistidine-ligated ferric C45 rapidly reacts with ABTS to form the green ABTS radical cation (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 5A). At the optimum reaction pH (pH = 8.58, Supplementary Fig. 6A, B) the reaction between C45 and H2O2/ABTS follows the ping-pong steady-state kinetics typical of natural peroxidases20 (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 7) (k cat = 1200 s−1; K m(H2O2) = 94 mM; K m(ABTS) = 379 μM), with exceptional catalytic efficiency for the electron transfer between peroxide-activated C45 and ABTS (k cat/K m = 3.2 × 106 M−1 s−1). This catalytic efficiency is among the highest observed in a de novo enzyme and matches well that of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) operating at its optimal pH (k cat = 4100 s−1; K m(ABTS) = 800 μM; k cat/K m(ABTS) = 5.13 × 106 M−1 s−1)21. Despite the high efficiency of the electron transfer step, the activation of peroxide by C45 is less catalytically efficient than in HRP (C45 k cat/K m = 1.3 × 104 M−1 s−1; HRP k cat/K m = 4.6 × 106 M−1 s−1 at pH 7.5)22, and is likely due to the lack of peroxide-activating amino acid side chains in the vicinity of the heme. Compared to other de novo heme-containing proteins that exhibit peroxidase activity, C45 is markedly more catalytically efficient and does not require helix-stabilizing additives such as trifluoroethanol for catalytic activity23–25. C45 is remarkably resilient to both elevated temperature (Fig. 2c) and the presence of organic solvents (Supplementary Fig. 6C, D), and retains impressive catalytic efficiency close to its denaturation temperature.

Fig. 2.

Steady-state kinetics of ABTS and hydrogen peroxide turnover by C45. a Transformation of ABTS to a green radical cation as catalyzed by natural peroxidases and C45. b Steady-state kinetics plot for ABTS turnover by C45 at varying [ABTS] and [H2O2]. Data are fit to a ping-pong steady-state kinetics model. c The thermal stability of C45 enables classical Michaelis–Menten kinetics to be determined up to 70 °C. All data were recorded in triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation. Michaelis–Menten parameters for the data contained in c are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Kinetic data were collected in 20 mM CHES, 100 mM KCl, pH 8.58 with 0.1 μM C45

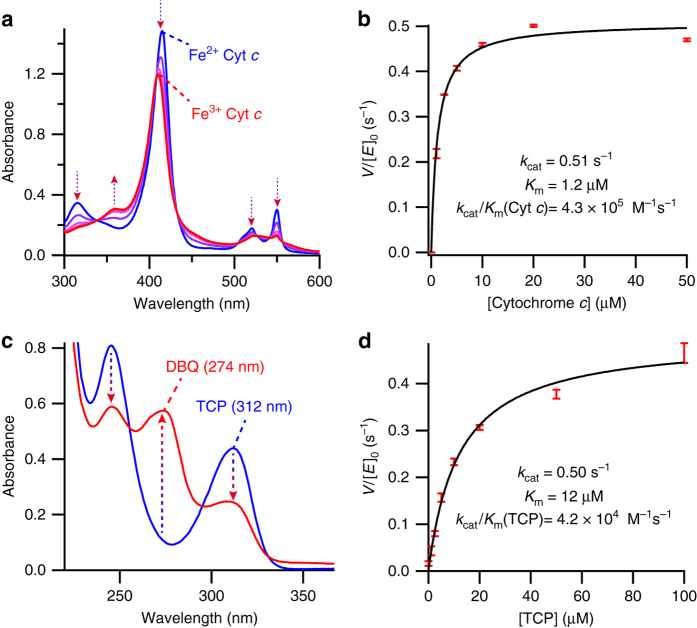

Previous work by Fry et al.26 has illustrated that heme maquettes can undergo rapid interprotein electron transfer with natural proteins such as cytochrome c, facilitated by complementary surface electrostatic interactions. Since C45 presents similar electrostatic surfaces to these maquettes, we reasoned that ferrous cytochrome c could act as an electron donor in the peroxidase reaction with C45, reproducing the activity of the natural cytochrome c peroxidases14. C45 is indeed capable of functioning as an efficient artificial cytochrome c peroxidase (Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary Fig. 5B), though the high K m(H2O2) of C45 precludes the determination of precise enzyme mechanism due to the high background rate of ferrous cytochrome c oxidation at millimolar H2O2 concentrations. We therefore fit the data to a simple Michaelis–Menten steady-state model with k cat here representing the observed maximum rate constant at limiting H2O2 concentration (100 μM). C45 exhibits impressive catalytic efficiency at limiting H2O2 concentrations (k cat/K m(cytc) = 4.3 × 105 M−1 s−1 vs. k cat/K m(cytc) = 1.62 × 107 M−1 s−1 for the natural yeast cytochrome c peroxidase27); however, under non-limiting concentrations of peroxide, we predict that k cat and k cat/K m(cytc) will be significantly increased. Nevertheless, this demonstrates the ability of C45 to couple interprotein electron transfer to a chemical transformation at a protein-bound heme, an intrinsic feature of respiratory enzymes such as cytochrome oxidase28.

Fig. 3.

Cytochrome c oxidation and TCP oxidative dehalogenation catalyzed by C45. a Representative changes to the UV/visible spectrum of equine cytochrome c during C45-catalyzed oxidation. b Michaelis–Menten plot of equine cytochrome c oxidation catalyzed by C45 in the presence of limiting H2O2 (100 μM). c Representative changes to the UV/visible spectrum of TCP during C45-catalyzed oxidative dehalogenation to the dichloroquinone product (DBQ). d Michaelis–Menten plot of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol oxidative dehalogenation catalyzed by C45 in the presence of limiting H2O2 (100 μM). All data were recorded in triplicate and error bars represent the standard deviation

Much like the natural heme-containing peroxidases14, C45 exhibits significant substrate promiscuity: it catalyzes the oxidation of peroxidase substrates including guaiacol, p-anisidine, o-phenylenediamine, 5-aminosalicylic acid, luminol, reactive blue 4, reactive black 5, and the anti-tuberculosis prodrug, isoniazid (Supplementary Fig. 8). This catalytic promiscuity also extends to the oxidative dehalogenation of halogenated phenols such as 2,4,6-trichlorophenol (TCP) (Supplementary Fig. 5C) and its bromo-analog and fluoro-analog, and 4-bromophenol. Like the ferrous cytochrome c oxidation described above, the mechanistic interrogation of TCP dehalogenation by C45 and H2O2 is hampered by the high C45 K m(H2O2) and incompatibility of the assay with millimolar [H2O2], and the data were therefore analyzed using a simple Michaelis–Menten model (Fig. 3c, d) at a limiting hydrogen peroxide concentration (100 μM). Compared to the dehaloperoxidase from Amphitrite ornata 29, an enzyme with a globin evolutionary heritage, C45 improves 5-fold on the natural enzyme’s catalytic efficiency at this limiting H2O2 concentration (k cat/K m(TCP) = 4.2 × 104 M−1 s−1 vs. k cat/K m(TCP) = 8.1 × 103 M−1 s−1 for DHP A). We predict k cat and k cat/K m(TCP) values at non-limiting H2O2 concentrations also to be significantly higher than for the natural enzyme.

Isolation of a reactive intermediate

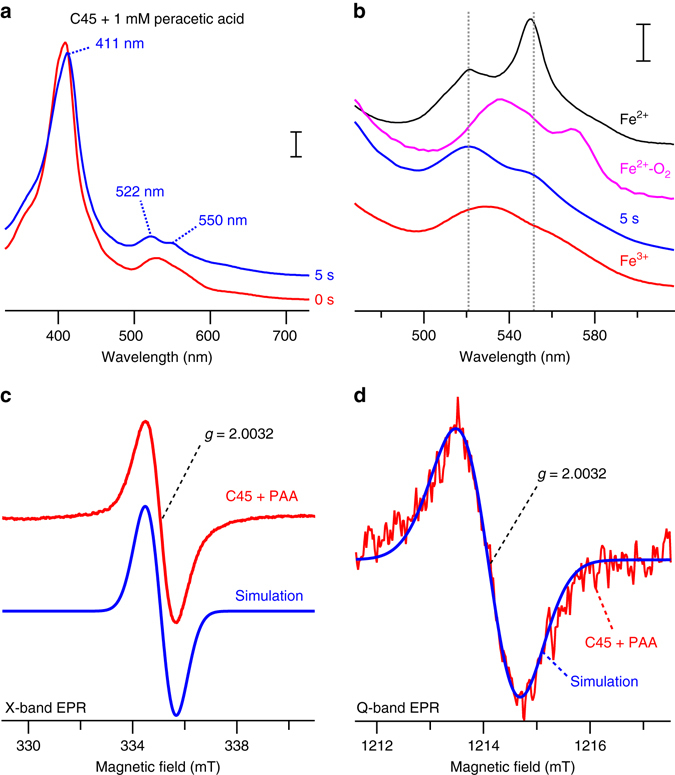

To further probe the artificial peroxidase mechanism, we rapidly mixed ferric C45 with hydrogen peroxide or organic peracids in a stopped flow spectrophotometer. Approximately 5 s later, we observed a spectroscopic intermediate (Fig. 4a, b) resembling cytochrome c peroxidase compound I27. We subsequently examined this intermediate using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy and observed the appearance of a new narrow EPR signal centered around g = 2.0032 with a line width of 1.1 mT (peak to peak). Microwave power saturation experiments at X-band and Q-band (34 GHz) suggest that this is an isolated species indicative of an amino acid-based radical. The lack of any discernible g-anisotropy at 34 GHz indicate a tryptophan side chain as the origin of this radical species (most likely W43 which is closest to the heme), analogous to the characteristics of cytochrome c peroxidase compound I30, 31.

Fig. 4.

Isolation of high-valent oxo-iron species in a CTM. a, b UV/visible spectra of ferric C45 (red) and peracetic acid-treated C45 (blue) obtained by rapid mixing experiments in a stopped-flow spectrophotometer. Ferrous (black), Ferric (red), and oxyferrous C45 (magenta) spectra are displayed for comparison. The putative C45 compound I species in a, b were generated by mixing 2 mM peracetic acid with 20 μM ferric C45 in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58. Scale bars represent optical densities of 0.05 (a) and 0.02 (b). c X-band cw-EPR spectrum of C45 mixed with peracetic acid (red) indicates the formation of a radical species with g = 2.0032. Simulated data of a tryptophan radical species within C45 are presented in blue. Spectra were obtained by mixing 1 mM peracetic acid with C45 (700 μM) in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58. Experimental conditions: EPR microwave frequency = 9.3933 GHz, microwave power = 1 mW, modulation amplitude = 0.3 mT, temperature = 12 K. d Q-band cw-EPR spectrum of C45 mixed with peracetic acid (red, conditions as for the X-band EPR data) and simulated data of a tryptophan radical species in C45 are presented in blue. The lack of observable g-anisotropy of the radical signal indicates the presence of an amino acid side chain-based radical species. Experimental conditions: EPR microwave frequency = 34.027 GHz, microwave power = 3 μW, modulation amplitude = 0.3 mT, temperature = 50 K

NMR spectroscopy and computational modeling

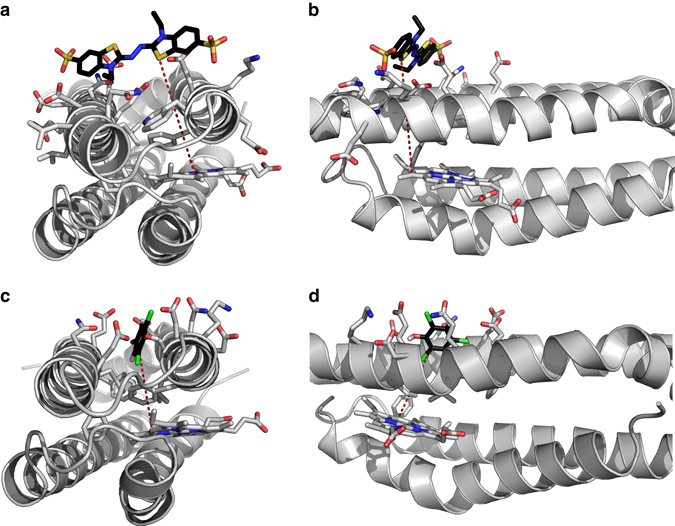

Despite the apparently dry interior of the protein, the 1D 1H and 2D 1H-15N SOFAST HMQC NMR spectra indicates that ferric C45 exists in a conformationally heterogeneous and dynamic state as evidenced by relatively low-peak dispersion (Supplementary Fig. 9B). However, C45 forms a discrete, monomeric, and thermally stable structure with scant evidence of conformational heterogeneity during oxygen binding. These structural characteristics and rather unusual 1H-15N spectra are observed in many heme-containing maquettes3, 12 and de novo proteins32, and evidently do not inhibit efficient peroxidase activity in C45. Indeed, there are notable examples of natural and engineered enzymes that exhibit analogous flexibility either globally or locally at the active site33–35. In these cases, the substrate is thought to confer structural rigidity through the induced-fit mechanism, though to date we have no experimental evidence of this behavior in C45. Though conventional substrate-binding sites are observed in some natural peroxidases, such as ascorbate peroxidase36, there are peroxidases for which the precise substrate:protein interactions are not definitively known14 and others where substrate is proven to associate at the enzyme surface rather than a well-defined cavity within the protein (e.g., lignin peroxidase)37. To investigate the structure and substrate interactions of C45, we constructed a computational model of C45 using Chimera38 and ran multiple 1 μs molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using GROMACS39 with the CHARMM27 forcefield40. C45 converges to a stable structure after 40 ns of simulation (Supplementary Fig. 10A), adopting a non-coiled-coil 4-helix bundle consistent with simulations of previous CTMs13 (Supplementary Fig. 10B, C). We then selected 10 snapshots of the 1 μs C45 MD simulations to capture conformational heterogeneity at the amino acid side-chain level. These 10 snapshots were then probed for ABTS and TCP binding using BUDE (Bristol University Docking Engine)41 in surface scanning mode, running a further 10 ns of MD simulation on the top 30 BUDE-derived complexes with highest binding energies. While the calculations indicate that ABTS may bind in up to 10 sites on the surface of the protein with similar binding energies (Fig. 5a, b; Supplementary Fig. 11A–C), there are relatively few hotspots for TCP binding despite the variation in side chain conformation in the starting C45 poses (Supplementary Fig. 11D–G). Furthermore, the highest calculated binding energy for TCP is for a cleft close to the heme (<10 Å) (Fig. 5c, d), ideal for the rapid electron tunneling necessary to support the observed catalytic rate42. This binding mode is stable in MD simulations. The two computational methods concur in identifying the binding site for TCP, suggestive of binding with good affinity and the indications are that this substrate-binding site is relevant for catalytic activity, offering potential for enhancing specify through designed modification. Despite the differences between the ABTS and TCP-binding interactions with C45, the substrate binding hotspots are all found at the protein surface. We therefore surmise that C45 behaves in a similar manner to lignin peroxidase37 and other natural peroxidases, presenting an interaction surface for substrate to dock prior to rapid electron transfer to the reactive heme intermediates.

Fig. 5.

Computational scanning for substrate–C45 interactions. a, b Single snapshot from an MD simulation of lowest energy ABTS-binding site on the C45 surface derived from BUDE. c, d Single snapshot from MD simulation of lowest energy TCP-binding site on the C45 surface derived from BUDE. The carbons of the substrates are colored black for clarity

Discussion

Our simple, systematic construction of a functional de novo enzyme highlights the power and utility of the maquette approach to functional oxidoreductase design. Similar to the construction of the original oxygen-binding maquette11, the engineering steps required to attain the desired catalytic function in this simple protein scaffold are few in number, reflecting the relative ease with which evolutionarily naive proteins can be rationally engineered in a tractable, iterative process. In this case, the concomitant restriction of conformational flexibility and removal of a heme ligand were sufficient to attain efficient, multistep catalysis within a heat-resistant and solvent-resistant maquette chassis, representing just three amino acid substitutions from the oxygen-binding progenitor. Despite the relatively low-catalytic efficiency of hydrogen peroxide turnover (104 M−1 s−1), the enzymatic rate constant k cat(ABTS) is among the highest yet observed in a de novo enzyme, and k cat/K m(ABTS) is greater than the catalytic efficiencies of the best reported de novo enzymes5, 8. Given the lack of a highly specific substrate-binding site, it is perhaps unsurprising that C45 exhibits broad substrate promiscuity. However, this catalytic promiscuity may be a general feature of primitive, nascent enzymes43. Since C45 is fully assembled in vivo, there is now a tantalizing opportunity to employ both rational protein design and directed evolution methodologies to optimize the catalytic chassis toward a selected substrate or chemical mechanism. We therefore anticipate that the descendants of this de novo designed enzyme will act as cheap, green, and catalytically proficient catalysts for industrial biotechnology and versatile bioblocks for synthetic biology, while providing insight into the rules underpinning the engineering of natural and designed enzymes.

Methods

General

All chemicals were purchased from either Sigma or Fisher Scientific, and T7 Express competent cells and Q5 polymerase were purchased from NEB.

Molecular biology, protein expression, and purification

Mutagenesis was performed using the ligase-independent cloning/mutagenesis method of Tillett44. Artificial CTMs were purified from E. coli using established procedures12, 13. To inhibit proteolysis, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride was added to the resuspended cell pellets. These cell pastes were then lysed by sonication (Soniprep plus MSE) and the soluble lysate was collected by centrifugation (40,000 × g for 30 min). This was then filtered (0.22 μM syringe filter, Millipore) and applied to a 5 ml HisTrap HP IMAC column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 40 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Potassium Phosphate at pH 8.0 (lysis buffer). The bound protein was then washed with lysis buffer (50 ml) and eluted with a linear gradient (0–100%) of 250 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Potassium Phosphate at pH 8.0 (elution buffer). SDS PAGE gel analysis revealed the cleanest fractions from the column, which were subsequently pooled and dialysed for 16 h against 5 liters of 0.5 mM EDTA and 20 mM Tris pH 8.0 in a 3 kDa semi-permeable dialysis membrane. 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) or dithiothreitol (DTT) was then added to the dialysed protein and TEV protease (1 μM) was added under anaerobic conditions (Belle Technology Glove Box, <5 p.p.m. O2) to facilitate cleavage of the N-terminal hexahistidine tag. Cleavage was complete after 5 h, and the protein was centrifuged (4000 × g, 10 min) and filtered (0.22 μM syringe filter, Millipore) to remove precipitated TEV protease. The protein was then loaded onto a HisTrap IMAC column equilibrated with lysis buffer as described above. Protein lacking the N-terminal hexahistidine tag eluted in the column flow through and was then placed in centrifugal concentrators (10 kDa Vivaspin Sartorius Stedim) to sufficiently increase concentration for the subsequent purification steps.

If HPLC-purification was required, the following procedure was followed using a Varian SD HPLC system: a C-18 reversed-phase HPLC column (Phenomenex) was equilibrated with 30% acetonitrile: 70% water (both with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid). Samples (0.5 ml) were then loaded on the column at 5 ml/min and following application of 25 ml of 30% acetonitrile, a linear gradient of 30–55% acetonitrile was applied. Absorbance was monitored at 280 and 395 nm to enable assessment of protein and heme content of the eluted fractions. Fractions containing the highest heme:protein ratio from a single peak were pooled and lyophilized to remove acetronitrile and trifluoroacetic acid. Proteins were then resuspended in appropriate buffer as stated in the respective methods.

Alternatively, it was found that size-exclusion chromatography was sufficient to produce clean CTM samples. Therefore, if HPLC was not employed, then the following procedure was followed: CTM samples were concentrated to approximately 1.5 ml with a centrifugal concentrator (10 kDa Vivaspin Sartorius Stedim) and split into three 0.5 ml samples that were loaded in separate runs onto a HiLoad Superdex 75 PG column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58, and flowing at 1 ml/min. Samples eluted in two distinct peaks, the first was aggregated protein and the second was pure maquette. The maquette peak was collected, concentrated to approximately 300 μM, and stored at 4 °C for further analysis.

Electronic spectroscopy and stopped-flow spectrophotometry

All UV-visible spectra were recorded on an Agilent Cary-60 UV-visible spectrophotometer. CTM samples were reduced by the addition of a few grains of sodium dithionite. To confirm the presence of c-type heme and to enable accurate determination of heme extinction coefficients, the pyridine hemochrome method of Berry et al.45 was employed. Using the pyridine hemichrome and hemochrome ε 550 nm (32,700 and 8430 M−1 cm−1), extinction coefficients of ε 406 nm = 147,300 M−1 cm−1 and ε 420 nm = 119,900 M−1 cm−1 were determined for the ferric and ferrous C45 Soret absorption bands.

To examine the pH-dependence of the ferric UV/visible spectrum of C45, 5 μM samples of C45 were prepared at pHs between pH 6.5 and 11.0. For pHs 6.0–6.5, 7.0–8.25, 8.5–10, and 10.5–11.0, the buffers employed were Bis-Tris, Tris, CHES, and CAPS, respectively, all at 50 mM. UV/visible spectra of the samples were measured and the Soret λmax was subsequently plotted vs. pH and fitted to a double ionization model yielding two pK a values.

Oxygen-binding kinetics of C45 were determined using a SX20 Stopped Flow Spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics) housed in an anaerobic glove box under N2 ([O2] <5 p.p.m.; Belle Technology). C45 samples (5 μM) in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58 were passively degassed in the anaerobic box overnight and then reduced with a stoichiometric quantity of sodium dithionite. Using the stopped flow spectrophotometer, ferrous C45 was then rapidly mixed with oxygenated buffer (540 μM O2 in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58) at 15 °C. Oxygen concentration was determined using a Lutron PDO-520 oxygen probe. Full spectra were collected over 1 or 100 s using a diode array detector, and a single wavelength corresponding to oxyferrous C45 (569 nm) was plotted against time. This trace was then fit to two consecutive single exponential functions representing the formation of the oxyferrous complex (0–0.04 s) and its subsequent autoxidation (0.04–100 s).

Possible reactive intermediates in C45 catalysis were generated by rapidly mixing 2 mM H2O2 or 2 mM peracetic acid with 20 μM ferric C45 (in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58) using an SX20 Stopped Flow Spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics) at 5 °C. Full UV/visible spectra were collected for at least 10 s after mixing.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

A JASCO J-815 CD polarimeter was used to measure circular dichroism spectra. Samples were typically loaded at concentrations of 0.015–0.15 mg/ml (1–10 μM) in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58 into a 1 mm pathlength quartz cell. Far-UV CD spectra were recorded at 100 nm/min with a sensitivity of 50 mdeg. To assess the thermal stability of the proteins, a ramp rate of 40 °C/h with 1 °C intervals was used and the ellipticity at 222 nm was measured throughout. The raw data were converted to mean residue ellipticity using the protein concentration and cell pathlength. The thermal denaturation midpoints (T ms) were assessed by plotting the second derivatives of the denaturation traces, the x-axis intercept corresponding to the T m.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Solutions of 0.5 mM CTM were prepared in redox buffer containing 10% v/v D2O (Sigma Aldrich, UK). 1D and 2D 1H-15N SOFAST HMQC spectra46 were acquired using a Shigemi tube (Sigma Aldrich, UK) on 30 μl of this solution using a 700 MHz Bruker AVANCE HD NMR spectrometer equipped with a 1.7 mm microcryo-coil triple resonance probe. 15N-enriched C45 was prepared by adding 1 g of 15NH4Cl (Cambridge Isotopes) to 1 liter of LB culture medium at the point of induction with isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), following the procedure described above. It should be noted that we were unable to obtain holoprotein with heme C covalently attached when attempting to isotopically label C45 in minimal medium. Demetallated C45 was obtained using the HF:pyridine method as described previously12.

EPR spectroscopy

Hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid (1 mM) was added to C45 (700 μM in 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58) in suprasil quartz sample tubes and flash frozen. X-band cw-EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker eleXsys E500 spectrometer using a standard rectangular Bruker EPR cavity (ER4102T) equipped with an Oxford helium cryostat (ESR900). Experimental parameters: microwave power, 1 mW; field modulation amplitude, 3 G; field modulation frequency, 100 kHz; measuring time 160 s; temperature 12 K. Q-band cw-EPR spectra were performed on a Bruker eleXsys E-560 spectrometer using a ER 5106QT-W1 resonator equipped with a home-built ARS cryogen-free cryostat. The measured spectra were corrected for an offset against a known g standard [1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl, g = 2.00351 ± 0.00002]. Spectral simulations were performed using the Matlab-based Easyspin package47.

Redox potentiometry

OTTLE potentiometry48 was used to measure heme redox potentials. CTMs (50–100 μM) were exchanged into 500 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 20 mM CHES, pH 8.58 and redox mediators (20 μM benzyl viologen, 20 μM anthroquinone-2-sulfonate, 20 μM phenazine, 25 μM 2-hydroxy-1,4-napthoquinone, 6 μM indigotrisulfonate, and 50 μM duroquinone) were added to facilitate equilibration between the electrodes and the redox cofactor. A home-built OTTLE cell was used for the measurements as previously described13, 48, consisting of a modified flat, quartz EPR tube (Wilmad, USA) with a platinum gauze working electrode, platinum counter electrode and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode (BASi, USA). A Biologic SP-150 potentiostat was used to apply potentials across the cell (+50 to −350 mV vs. NHE) in both reductive and oxidative directions to confirm equilibration, as evidenced by the lack of hysteresis in the data. To determine the heme reduction potentials, the wavelength corresponding to the heme Soret λmax was plotted against the applied potential and the data were subsequently fitted to functions corresponding to a single electron (Eq. (1)) or 2 × single electron (Eq. (2)) Nernst functions

| 1 |

| 2 |

In Eq. (1), A and B are y-axis values at 100% oxidized and reduced heme respectively; E m is the heme reduction potential. In Eq. (2), A and C are y-axis values at 100% oxidized and reduced heme, respectively, and B represents the point on the y-axis where there is a changeover between absorbance contributions from the first and second electron processes; E m1 and E m2 are the heme reduction potentials.

Steady-state kinetics

Steady-state kinetics of ABTS oxidation by C45 and H2O2 (where [ABTS] was varied) were carried out either in a 1 ml cuvette using an Agilent Cary-60 UV-visible spectrometer or on 96-well plate format (total volume per well = 300 μl) using a CLARIOstar plate reader (BMG Labtech). Unless specified, all enzymatic assays were carried out at 25 °C; enzymatic assays at elevated temperature were carried out in 1 ml cuvettes using an Agilent Cary-60 UV/visible spectrometer equipped with a TC 1 Peltier and BATH 10 circulator (Quantum Northwest). For assays conducted using the CLARIOstar plate reader, solutions of C45 and ABTS were prepared in a Sterilin 96-well plate (Thermo Fisher) at varying [ABTS] using a robotic liquid handling platform (Tecan). In all cases, reactions were initiated by the addition of H2O2 and the formation of the ABTS radical cation was monitored at 405 nm (ε 405 nm = 36,800 M−1 cm−1)49. Steady-state kinetics of H2O2 reduction by C45 and ABTS (where [H2O2] was varied) were carried out using a SX20 (Applied Photophysics) or HI-TECH SF-61DX2 Stopped Flow Spectrophotometer as the reaction rates were too rapid to enable measurement on a plate reader or in the standard 1 ml cuvette methods described above. 0.1 μM C45 and 24 mM ABTS (in 20 mM CHES, 100 mM KCl, pH 8.58) were rapidly mixed with varying concentrations of H2O2 between 0 and 1 M. The formation of the ABTS radical cation was followed at 525 nm (ε 525 nm = 4250 M−1 cm−1). Data were recorded in triplicate and fit to a ping pong steady-state model (Eq. (3)) using the Dynafit software package50.

| 3 |

To determine the pH optimum and corresponding pK a’s, ABTS oxidation kinetics were obtained at pH 6, 7, 8 (20 mM Potassium Phosphate), 8.5, 9, 10 (20 mM CHES), and 11 (20 mM CAPS). Data were fit to a double ionization model as described above.

Ferrocytochrome c was produced by reducing horse heart cytochrome c with sodium dithionite. Excess dithionite was removed using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) and the concentration of ferrocytochrome c was determined using ε 550 nm = 29,500 M−1 cm−1. The reaction kinetics were determined pH 8.58 by monitoring the disappearance of the cytochrome alpha band at 550 nm and data were fit to a simple Michaelis–Menten steady-state model.

A stock solution of TCP was prepared by dissolving 2 mg of TCP in 100% ethanol and then the required TCP concentrations were obtained through serial dilution. TCP concentrations were determined using the extinction coefficient at 312 nm (ε 312 nm = 5290 M−1 cm−1)51. Steady-state kinetics were recorded at pH 8.58 as described above for ABTS. The reaction kinetics were determined by monitoring the formation of the dichloroquinone product (ε 272 nm (of DCQ—TCP) = 11,670 M−1 cm−1) and the kinetic data were fit to a simple Michaelis–Menten steady-state model.

To determine the effects of organic solvents, ABTS oxidation and TCP oxidative dehalogenation were carried out in the presence of increasing concentrations of ethanol and methanol, respectively. Data were collected and analyzed as described above.

Computational methods

MD simulations of C45 were performed using GROMACS 4.6.4 (www.gromacs.org) running on local workstations and the University of Bristol HPC BlueCrystal. Gromacs tools were used to add hydrogen atoms consistent with pH 7, set up a cubic periodic box 0.18 nm large than the largest dimension of the protein and solvate the box with TIP3P water and 150 mM sodium chloride ions, ensuring overall charge neutrality. The CHARMM27 force field was modified to include heme C parameters, derived from the standard CHARMM heme B parameters52. An initial energy minimization was performed using steepest descents until the maximum force on any atom was less than 200 kJ mol−1 nm−1. Long-range electrostatics were treated with particle mesh Ewald (PME) and simulations performed as isothermal–isobaric ensemble (NPT) ensembles at 300 K and 1 bar maintained with v-rescale temperature coupling and isotropic Berendsen pressure coupling. An equilibration simulation was performed for 200 ps while restraining the protein atoms to their original positions. After removing restraints, the simulation was continued for 100 ns saving frames every 1 ns. Analysis and visualization was performed with the Gromacs tools and Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD).

BUDE surface scanning mode was used for the C45 substrates ABTS and TCP on 10 different snapshots from a Gromacs MD simulation of C45. The snapshots were taken every 10 ns during the 100 ns simulation. The structures of the ligands were obtained from the ZINC database online and parameterized with the program acpype.py using Antechamber and the General Amber Force Field53–55. The BUDE setup, BUDE running, processing for MD, MD setup, and MD post-processing was scripted where appropriate. Each combination of ligand and snapshot of C45 simulation (receptor) had 1200 randomly assigned surface positions explored. At each surface position the ligand was docked using the BUDE EMC method (a cut-down GA) whereby 3000 initial poses were developed for a further 10 generations, expanding the 30 best parents to 3000 children each generation. In total 1.08 × 1010 conformations were sampled per ligand with C45. The top 50 binding modes per ligand were then processed and run as a 10 ns Gromacs simulations as described above.

Data availability

All data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported at the University of Bristol by the BBSRC (grant no: BBI014063/1 and BB/M02315X/1), the Royal Society through a University Research Fellowship to J.L.R.A. and a Wolfson Research Merit Award to F.M., the ERC and BBSRC DTG for studentship for D.W.W., the BBSRC SWDTP for studentship for J.M.X.J. The authors wish to thank Prof. Dek Woolfson (Bristol) for kindly providing access to his equipment, Dr Chris Williams (Bristol) for help with acquiring the NMR spectra, and Dr Steve Burston (Bristol) for helpful discussions. We wish to thank the University of Bristol for access to the High-Performance Computing machine BlueCrystal via the Advanced Research Computing Centre (https://www.acrc.bris.ac.uk).

Author contributions

D.W.W., J.M.X.J., N.W., R.B.S., A.J.M., S.M., and J.L.R.A. designed the experiments. D.W.W., J.M.X.J., N.W., J.S., K.G., K.L.V., and H.J.B. performed the measurements; M.I.G. and M.P.C. recorded and analyzed the NMR spectra; G.C. aided the analysis of the enzyme kinetics; A.S.M. and F.M. recorded and analyzed the EPR spectra. All authors analyzed the data and contributed to the manuscript preparation; J.L.R.A. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00541-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nanda VK, Koder RL. Designing artificial enzymes by intuition and computation. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:15–24. doi: 10.1038/nchem.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watkins DW, Armstrong CT, Anderson JLR. De novo protein components for oxidoreductase assembly and integration. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014;19:90–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farid TA, et al. Elementary tetrahelical protein design for diverse oxidoreductase functions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:826–833. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Röthlisberger D, et al. Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature. 2008;453:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nature06879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blomberg R, et al. Precision is essential for efficient catalysis in an evolved Kemp eliminase. Nature. 2013;503:418–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiss G, Celebi-Olcum N, Moretti R, Baker D, Houk KN. Computational enzyme design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:5700–5725. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reig AJ, et al. Alteration of the oxygen-dependent reactivity of de novo due ferri proteins. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:900–906. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zastrow ML, Peacock AFA, Stuckey JA, Pecoraro VL. Hydrolytic catalysis and structural stabilisation in a designed metalloprotein. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:118–123. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tebo AG, Pecoraro VL. Artificial metalloenzymes derived from three-helix bundles. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015;25:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nastri F, et al. Design and engineering of artificial oxygen-activating metalloenzymes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:5020–5054. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00923E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koder RL, et al. Design and engineering of an O2 transport protein. Nature. 2009;458:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature07841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson JLR, et al. Constructing a man-made c-type cytochrome maquette in vivo: electron transfer, oxygen transport and conversion to a photoactive light harvesting maquette. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:507–514. doi: 10.1039/C3SC52019F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins DW, et al. A suite of de novo c-type cytochromes for functional oxidoreductase engineering. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1857:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poulos T. Heme enzyme structure and function. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:3919–3962. doi: 10.1021/cr400415k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zahn JA, Arciero DM, Hooper AB, Dispirito AA. Cytochrome c′ of methylococcus capsulatus bath. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;240:684–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0684h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace CJA, Clark-Lewis I. Functional role of heme ligation in cytochrome c. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:3852–3861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss R, Gold A, Terner J. Cytochromes c′: biological models for the S=3/2, 5/2 spin-state admixture? Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2550–2579. doi: 10.1021/cr040416l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonini, E. & Brunori, M. Hemoglobin and Myoglobin in Their Reactions with Ligands 47–48 (North-Holland Pub. Co., 1971).

- 19.Lu I, Casimiro DR, Bren KL, Richards JH, Gray HB. Structurally engineered cytochromes with unusual ligand-binding properties: expression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Met80Ala iso-1-cytochrome c. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:11456–11459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunford, H. B. in Peroxidases in Chemistry and Biology Vol. 2 (eds Everse, J., Everse, K. E. & Grisham, M. B.) 1–24 (CRC Press, 1991).

- 21.Savenkova MI, Kuo JM, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Improvement of peroxygenase activity by relocation of a catalytic histidine within the active site of horseradish peroxidase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10828–10836. doi: 10.1021/bi9725780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neptuno Rodriquez-Lopez J, Smith AT, Thorneley RNF. Role of arginine 38 in horseradish peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:4023–4030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moffet DA, et al. Peroxidase activity in heme proteins derived from a designed combinatorial library. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7612–7613. doi: 10.1021/ja001198q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faiella M, et al. De novo design, synthesis and characterization of MP3, a new catalytic four-helix bundle hemoprotein. Chemistry. 2012;18:15960–15971. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vitale R, et al. An artificial heme-enzyme with enhanced catalytic efficiency: evolution, functional screening and structural characterization. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;17:4859–4868. doi: 10.1039/C5OB00257E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fry BA, Solomon LA, Dutton PL, Moser CC. Design and engineering of a man-made diffusive electron-transport protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1857:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy EJ, Metcalfe CL, Basran J, Moody PC, Raven EL. Engineering the substrate specificity and reactivity of a heme protein: creation of an ascorbate binding site in cytochrome c peroxidase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13933–13941. doi: 10.1021/bi801480r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshikawa S, Shimada A. Reaction mechanism of cytochrome c oxidase. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:1936–1989. doi: 10.1021/cr500266a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le P, Zhao J, Franzen S. Correlation of Heme binding affinity and enzyme kinetics of dehaloperoxidase. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6863–6877. doi: 10.1021/bi5005975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casadei CM, et al. Neutron cryo-crystallography captures the protonation state of ferryl heme in a peroxidase. Science. 2014;345:193–197. doi: 10.1126/science.1254398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvey JN, Bathelt CM, Mulholland AJ. QM/MM modeling of compound I active species in cytochrome P450, cytochrome c peroxidase, and ascorbate peroxidase. J. Comput. Chem. 2006;27:1352–1362. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy GS, Griesman JB, Hecht MH. De novo proteins with life-sustaining functions are structurally dynamic. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vamvaca K, Vogeli B, Kast P, Pervushin K, Hilvert D. An enzymatic molten globule: efficient coupling of folding and catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12860–12864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404109101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulengerg C, Stark Y, Kunzle M, Hilvert D. Comparative laboratory evolution of ordered and disordered enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:9310–9320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.638080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forouhar F, et al. Molecular insights into substrate recognition and catalysis by tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:473–478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610007104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharp KH, Mewies M, Moody PE, Raven EL. Crystal structure of the ascorbate peroxidase-ascorbate complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:303–307. doi: 10.1038/nsb913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miki Y, et al. Crystallographic, kinetic, and spectroscopic study of the first lignolytic peroxidase presenting a catalytic tyrosine. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:15525–15534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.220996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berendsen HJC, van der Spoel D, van Drunen R. GROMACS: a message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:43–56. doi: 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00042-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindahl E, Bjelkmar P, Larsson P, Cuendet MA, Hess B. Implementation of the CHARMM force field in GROMACS: analysis of protein stability effects from correction maps, virtual interaction sites, and water models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:459–466. doi: 10.1021/ct900549r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McIntosh-Smith S, Price J, Sessions RB, Ibarra AA. High performance in silico virtual drug screening on many-core processors. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl. 2015;29:119–134. doi: 10.1177/1094342014528252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moser CC, Anderson JLR, Dutton PL. Guidelines for tunneling in enzymes. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:1573–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.04.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen RA. Enzyme recruitment in evolution of new function. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 1976;30:409–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.30.100176.002205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiu J, March PE, Lee R, Tillett D. Site-directed, ligase-independent mutagenesis (SLIM): a single-tube methodology approaching 100% efficiency in 4 h. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e174. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berry EA, Trumpower BL. Simultaneous determination of hemes a, b and c from pyridine hemochrome spectra. Anal. Biochem. 1987;161:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schanda P, Kupce E, Brutscher B. SOFAST-HMQC experiments for recording two-dimensional heteronuclear correlation spectra of proteins within a few seconds. J. Biomol. NMR. 2005;33:199–211. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-4425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stoll S, Schweiger A. EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 2006;178:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ost TWB, et al. 4-cyanopyridine, a versatile spectroscopic probe for cytochrome P450BM3. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48876–48882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Childs RE, Bardsley WG. The steady-state kinetics of peroxidase with 2,2′azino-di(3-ethyl-benzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) as chromogen. Biochem. J. 1975;145:93–103. doi: 10.1042/bj1450093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuzmic P. Dynafit—a software package for enzymology. Methods Enzymol. 2009;467:247–280. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)67010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feducia J, et al. Characterization of dehaloperoxidase compound ES and its reactivity with trihalophenols. Biochemistry. 2009;48:995–1005. doi: 10.1021/bi801916j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Foloppe N, MacKerell AD., Jr. All-atom empirical force field for nucleic acids: I. Parameter optimization based on small molecule and condensed phase macromolecular target data. J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:86–104. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(20000130)21:2<86::AID-JCC2>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Irwin JJ, Sterling T, Mysinger MM, Bolstad ES, Coleman RG. ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012;52:1757–1768. doi: 10.1021/ci3001277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sousa da Silva AW, Vranken WF. ACPYPE—AnteChamber PYthon Parser interfacE. BMC Res. Notes. 2012;5:367. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Wang W, Kollman PA, Case DA. Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2006;25:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.