Abstract

Purpose of the review

Intestinal fibrosis is a common complication of several enteropathies with inflammatory bowel disease being the major cause. Intestinal fibrosis affects both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, and no specific anti-fibrotic therapy exists. This review highlights recent developments in this area.

Recent findings

The pathophysiology of intestinal stricture formation includes inflammation dependent and independent mechanisms. A better understanding of the mechanisms of intestinal fibrogenesis and the availability of compounds for other, non intestinal fibrotic diseases bring clincial trials in stricturing Crohn’s disease within reach.

Summary

Improved understanding of its mechanisms and ongoing development of clincial trial endpoints for intestinal fibrosis will allow the testing of novel anti-fibrotic compounds in inflammatory bowel disease.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, fibroblast, fibrosis, stricture

INTRODUCTION

Intestinal fibrosis is a common complication of several enteropathies with distinct pathophysiology, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), radiation enteropathy, graft-versus-host disease, collagenous colitis, eosinophilic enteropathy, drug-induced enteropathy, cystic fibrosis, intra-peritoneal fibrotic adhesions or desmoplastic reactions in gastrointestinal tumors leading to intestinal stenosis and obstruction. Of these enteropathies, IBD is the main cause of intestinal fibrosis since this disease is characterized by a persistent immuno-mediated intestinal inflammation (1, 2). It becomes clinically apparent in >30% of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and in about 5% with ulcerative colitis (UC). This review will highlight recent developments in the mechanisms of this complication and discuss what future therapies are available from organs other than the gut.

MORPHOLOGY AND MECHANISMS OF INTESTINAL FIBROSIS

CD-associated strictures are frequently unresponsive to any of the current anti-inflammatory drugs for CD and require alternative therapeutic approaches like endoscopic balloon dilation (3•), strictureplasty or bowel resection, and often recur after resection (2, 4, 5). Clinically, the CD fibrostenotic stricture needs to be distinguished from inflammation-related bowel wall thickening which may respond to anti-inflammatory therapy; the two often coexist, and their distinction is difficult since intestinal fibrosis follows the distribution and location of inflammation (6). In CD, fibrosis can involve the full thickness of the bowel wall (4, 7). It affects any part of the gastrointestinal tract and results in narrowing of the lumen leading to strictures that frequrntly cause intestinal obstruction. It has recently been reported that the smooth muscle hyperplasia/hypertrophy contributes to the majority of the CD stricturing phenotype, whereas fibrosis may be less significant (8•). In this report the authors proposed a novel histological grading system that covers not only inflammation and fibrosis but the full spectrum of inflammatory bowel disease pathology.

In UC extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition was believed to be restricted to the mucosal and submucosal layers of the large bowel and could be responsible for diarrhea and tenesmus even in the absence of inflammation (9). This paradigm has recently been questioned by Ippolito et al. (10•). Increased levels of ECM were observed throughout the full-thickness of the inflamed colonic wall in long-lasting ulcerative colitis, together with a cellular fibrotic switch in the tunica muscularis, which may be responsible for the colon tubular appearance and dysmotility. An up-regulation of RhoA expression in muscle layers was found. RhoA signaling plays a relevant role in the fibrogenic differentiation of intestinal SMCs (10•, 11) and novel approaches to antifibrotic strategies have been investigated by pharmacologic modulation of the RhoA pathway (12).

Fibrosis is a consequence of local chronic inflammation and is characterized by excessive ECM protein deposition (1, 2, 6). ECM is produced by a transient or permanent numerical expansion of activated myofibroblasts, which are modulated by both pro-fibrotic and anti-fibrotic factors. Whereas in other organs the source of ECM-producing myofibroblasts is restricted to a few cell types, in the intestine the situation is more complicated as multiple cell types may become activated ECM-producing myofibroblasts (1, 2, 6, 13). These cells derive not only from resident mesenchymal cells (fibroblasts, subepithelial myofibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells) but also from epithelial and endothelial cells (via epithelial-mesenchymal transition [EMT]/endothelial-mesenchymal transition [EndoMT]), stellate cells, pericytes, and bone marrow stem cells. Myofibroblasts are activated by a variety of mechanisms including paracrine signals derived from immune and nonimmune cells, autocrine factors secreted by myofibroblasts, pathogen-associated molecular patterns derived from microorganisms that interact with pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and the so called damage-associated molecular patterns derived from injured cells, including DNA, RNA, ATP, highmobility group box proteins, microvesicles, and fragments of ECM molecules (1, 14). The intestinal microbiota (15) (16–18•) as well as dietary components (19–21•) have been recognized to potentially modulate both intestinal inflammation and fibrogenesis. However, at present, neither specific bacterial strains nor specific micronutrients with pro-fibrotic or anti-fibrotic action have been clearly identified. Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) may be a novel cell type interacting with mesenchymal cells in a profibrogenic fashion. The orphan nuclear receptor RORα is important in ILC development, and deletion of RORα can ameliorate experimental intestinal fibrosis, independent of eosinophils, STAT6 signaling and Th2 cytokine production. The mechanism appears to involve group 3 ILCs, IL-17A and IL-22 (22••).

Alterations of the smooth muscle cells due to activation by the overlying mucosal inflammation are well known (1, 2, 6, 13). A two-way communication between mucosal epithelial cells and smooth muscle cells, as well as between immune cells and smooth muscle cells, appears to exist. Several inflammatory stimuli, including cytokines involved in different types of immune responses (Th1, Th2 and Th17), are known to affect the function and structure of smooth muscle cells (23, 24). TGF-β1, the main driving factor of fibrosis, and IGF were found to promote the growth of smooth muscle cells (25, 26). In fibrostenotic CD, the TGF-β1 induces IGF-I and mechano-growth factor (MGF) production in intestinal smooth muscle and results in muscle hyperplasia/hypertrophy and collagen I production that contribute to stricture formation (27). Furthermore, noncanonical STAT3 activation regulates excess TGF-β1 and collagen I expression in muscle of stricturing Crohn's disease (28). A complex interaction between the ECM and smooth muscle cells may exist, suggesting that sequential changes characterized by chronic inflammation driving fibrosis lead to smooth muscle hyperplasia/hypertrophy. All these data are indicative of an important role of smooth muscle cells in CD-associated 'fibrostenosis', and this could also explain the promising results of treatment with pneumatic dilation and strictureplasty (5), which could act directly on the narrowing and stiffness of stenosis induced by the abnormal contractile activity of muscle hyperplasia/hypertrophy.

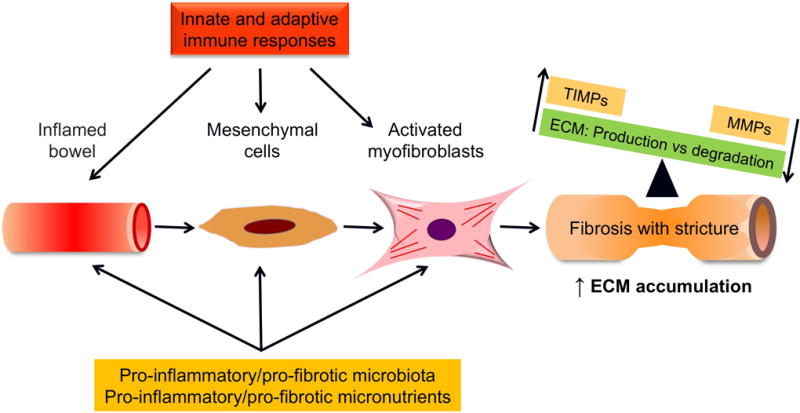

Fibrosis depends on the balance between the production and degradation of ECM proteins. ECM degradation is mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and the fine balance between MMPs and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) appears to be altered in intestinal fibrosis (1, 2, 6, 13, 14) (Fig. 1). It is unclear, however, which specific MMPs and TIMPs are involved in fibrosis and how they are regulated. In addition to playing a central role in ECM turnover, MMPs proteolytically activate or degrade a variety of non-matrix substrates including chemokines, cytokines, growth factors, and junctional proteins. Thus, they are increasingly recognized as critical players both in inflammatory response and fibrogenesis (29, 30). In fact, inhibition of MMP9 can prevente experimental fibrosis in mice (31•).

Fig 1. Mechanisms of intestinal fibrosis in inflammatory bowel disease.

Fibrogenesis is dynamic and multifactorial process, which is accompanied by an imbalance between matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases. Abbreviations: ECM-extracellular matrix; MMP-matrix metalloproteinase; TIMP- tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases.

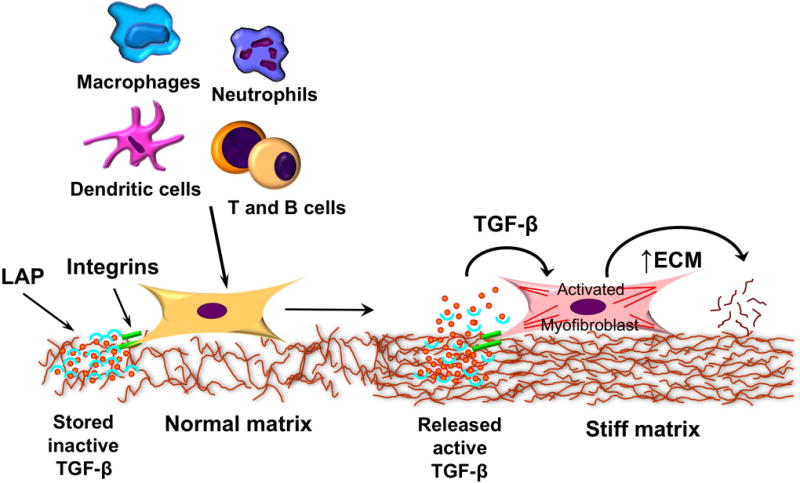

The composition and stiffness of fibrotic tissue appears to be involved in the progression of fibrosis (1, 2, 6, 13, 14). Tissue stiffness is determined by the composition and contraction of the ECM, as well as by the contractility of fibroblast, myofibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. The ECM is the storage site for cytokines and fibrotic growth factors, including TGF-β. These can be released and promoted myofibroblasts activation and deposition and crosslinking of ECM components changing its local mechanical properties and making it stiffer (32, 33). Interestingly, insightful observations, made in in vitro studies, suggest that stiffness of intestinal tissues can trigger morphological and functional changes in human colonic fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, from a non-proliferative to an activated fibrogenic myofibroblast phenotype (32–34). In this light, a stiff ECM could be considered not only as a result, but also as a source of tissue fibrosis in IBD, with a critical role in further progression of fibrosis (Fig. 2).

Fig 2. Extracellular matrix stiffness and progression of fibrosis.

Myofibroblasts can be activated by immune cells to increase the deposition of extracellular matrix. They respond to the stiffness of their matrix environment, which keeps them in a persistent activated phase, but also allows the release of TGF-β1 from the latency associated peptide through integrin mediated mechanisms. Abbreviations: ECM-extracellular matrix; TGF- transforming growth factor; LAP-latency associated peptide.

CLINICAL OBSERVATIONS SUGGESTING REVERSIBILITY OF INTESTINAL FIBROSIS

The conventional view that intestinal fibrosis is an inevitable and irreversible process in patients with IBD is gradually changing in light of an improved understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underline its pathogenesis (1, 2, 4). The concept of intestinal fibrosis has changed from being a static and irreversible entity to a dynamic and reversible condition, as seen in other organs including skin, kidney, lung, heart and liver, in which fibrosis has been shown to be reversible (35). Novel observations indicate that established intestinal strictures are reversible (35). After performance of strictureplasty in CD fibrosis regression at the site of the prior stricture can be observed (36), and fibrosis recurrence at a strictureplasty site is a rare event (37). On serial ultrasound examinations after strictureplasty, a reduced thickness and inflammation of the intestinal wall was found (38).

PROMISING THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES FROM OTHER ORGANS THAN THE GUT

Knowledge about mechanisms of intestinal fibrosis significantly lags behind that of other organs such as liver, kidney or lung. The concept that control of sustained injury can reduce fibrosis was shown in liver cirrhosis with the emergence of successful therapies against Hepatitis B (HBV) or C virus (HCV), but also with better control of liver injury of other etiologies (39). Up to 70% of patients with HBV or HCV cirrhosis show reversibility of fibrosis on follow-up biopsies (40, 41). Aside removing the trigger of injury, targeting the activation of myofibroblasts and deposition of ECM is promising. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib is approved for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy and targets broad signaling pathways of fibrosis. Multiple proliferative cytokines, including platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and TGF-β signal through tyrosine kinases. Sorafenib has been shown to be anti-fibrotic in experimental liver cirrhosis (42). Other examples for drugs targeting the same mechanism include imatinib (43) and nilotinib (44). Downstream intracelluar targets include ROCK, a kinase involved in the shape and movement of the cytoskeleton. Inhibition of ROCK reduced liver fibrosis (45). To choose a global approach for rendering future targets for anti-fibrotic therapy Wang et al. used whole genome expresison arrays in liver biopsy samples from chronically HBV infected patients. This unbiased approach followed by a functional analysis revealed integrin subunit β-like 1 (ITGBL1) as a crucial regulator of fibrogenesis (46•).

A concept that has been explored in liver nut not intestinal fibrosis is the pleiotropic and divergent action of macrophages, depending on the stage of fibrosis development. In the early stages of liver fibrosis, macrophages may act in a pro-fibrogenic fashion through TGF-β and PDGF-mediated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation. Macrophage depletion during the injury phase of experimental liver fibrosis resulted in decreased scarring and reduced numbers of myofibroblasts (47). In contrast, their depletion during the recovery phase of experimental liver fibrosis resulted in impaired scar resolution (47), indicating that this cell type has not only a role in initiation, but also in resolution of fibrosis depending on the timing of action. One possible mechanism could be mediated through the scavenger receptor stabilin-1 on marcrophages. Deficiency of stabilin-1 increased the expression of chemokine CCL3, exacerbated induction of fibrosis and delayed resolution during the recovery phase of experimental liver fibrosis. This is a novel pathway in which a failure to remove fibrogenic products of lipid peroxidation via a scavenger receptor drives fibrosis (48••).

In kidney fibrosis angiotensin II (Ang II) has been identified as a principal mediator of disease progression, acting via TGF-β. Inhibitors have shown promise in experimental models and humans (49–51) and this effect is independent of changes in blood pressure, making this therapy potentially transferable to IBD. Systemic inhibition of the chief pro-fibrotic mediator TGF-β1 poses a challenge due to possible side effects of inflammation and neoplasia, which is of particular concern in IBD. One possible approach is the inhibition of cell surface activation of TGF-β1 through blockade of the integrin receptor αVβ6 that is upregulated only in areas of injury and essential for its activation. Integrin antagonists have shown promise in experimental pulmonary fibrosis(52) and human antibodies are available. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is another mediator in the TGF-β1 pathway. A human CTGF antibody FG-3019 was safe and well tolerated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients in an open label phase 2 trial (53•) after showing efficacy in experimental models (54). Tumor protein p53 has been implicated in renal fibrogenesis. Yang and colleagues recently provided a mechanism by which p53 blockade attenuated experimental kidney fibrosis. It appears to signal through the microRNA miR-199a-3p, SOCS7 and STAT3 and the changes in this pathway could be recapitulated in human kidney fibrosis (55•).

Aging promotes inflammation, fibrosis and decline in organ function, as seen in cardiac fibrosis. Peptidylarginine deimidase 4 (PAD4) is a regulator of the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), an important feature of acute inflammation. Martinod et al. found increased NETs with aging associated with fibrosis and this observation could be prevented by deletion of PAD4 in experimental models of cardiac fibrosis. This suggests that PAD4 regulates age-related organ fibrosis and could be a novel anti-fibrotic target (56••).

The field of fibrosis has undergone transformation in the recent years. Significant strides have been undertaken to define and refine trial endpoints, leading to two new molecules approved for clinical use in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: pirfenidone and nintedanib (57). Pirfenidone combines anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory properties. It led to a 22.8% relative reduction in the decline of the forced vital capacity (FVC) and 26% improvement in progression free survival (58). When focusing on patients most benefitting from treatment the relative reduction in FVC decline increased to 47.9% (59). Nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, led to a 68.4% drop in the rate of annual FVC decline compared to placebo (60). Further clinical trials confirmed this efficacy (61). Taken together, this suggests that anti-fibrotic therapy is able to delay progression of lung fibrosis. One promising new concept is to facilitate tissue restitution to break the cycle of injury and repair leading to fibrosis. Liang at al. detected that the ECM component hyaluronan and TLR4 are critical in promoting type 2 alveolar epithelial cells, stem cells of the adult lung, augmenting repair of lung injury and limiting the amount of fibrosis (62••). The concept of targeting injury and repair is not restricted to the epithelium. Repetitive lung injury activates pulmonary capillary endothelial cells, promoting fibrosis through downregulation of the chemokine receptor CXCR7. Administration of CXCR7 agonist after experimental lung injury promotes lung repair and ameliorates fibrosis (63).

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the wealth of knowledge of fibrogenic mechanisms in the gut and elsewhere, the availabiliyt of various animal models, and indication that fibrosis is reversible in other organs, such as the lung, there is no anti-fibrotic available for IBD. The clinical problem is significant, affecting approximately 50% of patients with CD (2), and anti-fibrotic therapy would likely be chronically administered making this an attractive area for pharmaceutical companies. Nevertheless, there has not been a single trial for an anti-fibrotic in IBD to date. The field of intestinal fibrosis faces comparable obstacles to that of lung fibrosis about a decade ago: 1) The time from disease onset to development of clinically apparent fibrosis is long; 2) fibrosis clinically presents in late stages; 3) there are no reliable biomarkers for prediction, amount of fibrosis or response to therapy; 4) clincial trial endpoints are soft and non-validated.

From a perspective of a clinical trial in intestinal fibrosis a starting point would likely be already established fibrosis, given the lack of biomarkers that allow stratification of patients into high risk groups for progression to fibrosis. This way the long duration from disease onset to clinically apparent fibrosis can be circumvented, and instead reversal or lack of progression of already established fibrosis may be an appropriate endpoint. Utmost care should be exercised to select a population without the co-presence of internal penetrating disease due to unclear effects of therapies that influence tissue remodeling in these patients.

The biggest challenge lies in the selection of the clincial trial endpoints. The ideal endpoint should be non-invasive and correlate with a clinically relevant outcome. Several promising imaging techniques exist. Delayed enhancement MRI, which measures the contrast enhancement over a 7 minute period, has shown its ability to distinguish severe from moderate or mild fibrosis, but it is not able to separate mild from moderate fibrosis (64••). This technique uses altered tissue perfusion as a surrogate marker of intestinal fibrosis. Changes in tissue elasticity associated with fibrosis can be measured via ultrasound elastography, determining the ‘hardness’ or ‘softness’ of tissue (65). Shear wave elastography generates an ultrasonic pressure wave that correlates with tissue density and stiffness (66). Magnetization MRI (MT-MRI) has shown promise in animal models of intestinal fibrosis and pilot studies in humans demonstrate feasibility for separation of fibrosis and inflammation in stricturing CD (67, 68). A different approach is the direct detection of macromolecules, specifically collagen. MT-MRI is a technique that evaluates the exchange of protons between fixed macromolecules and surrounding water within a tissue (69).

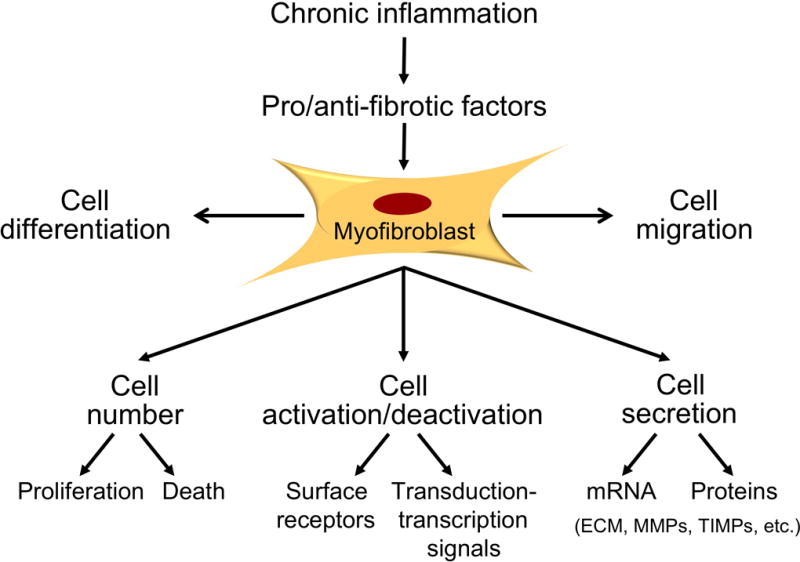

Ultimately the approach to therapy of intestinal fibrosis will be multimodal: we need to A) eliminate the primary cause of injury, B) improve control of the underlying intestinal inflammation and prevent or reduce tissue injury, C) target accumulation of ECM by blocking pro-fibrotic mediators and intracellular signaling pathways, and D) promote of the resolution of fibrosis (Tab. 1). Putative drugs treating established fibrosis can include agents able to reduce the activation of ECM-producing cells and their pro-fibrogenic properties (proliferation, motility, ECM deposition, contraction), agents with pro-apoptotic effect for ECM producing cells and agents able to increase ECM degradation (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Mechanisms potentially effective in the reversal of intestinal fibrosis

|

Fig 3. Schematic representation of potential therapeutic targets in intestinal fibrosis.

Abbreviations: ECM-extracellular matrix; MMP-matrix metalloproteinase; TIMP- tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases.

Although there is no specific medical therapy to treat fibrotic intestinal strictures, multiple compounds are now in clinical development or clinical practice in other organs than the intestine that could be employed in CD and may represent an entirely new class of drugs in the armentarium of IBD therapy.

KEY POINTS.

-

-

Intestinal fibrosis is a serious clinical problem

-

-

No specific anti-fibrotic therapies exist

-

-

Novel mechanisms are being discovered contributing to stricture formation in IBD

-

-

Mulitple anti-fibrotic compounds are becoming available from other organs, such as lung, liver, kidney

-

-

Novel developments in clinical trial endpoints put the clinical development of anti-fibrotic drugs within reach

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [T32DK083251, P30DK097948 Pilot, K08DK110415] and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation to F.R., and grants from the University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

None.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT OR SPONSORSHIP None.

ABBREVIATIONS

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- TGF

Transforming growth factor

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- TIMP

Tissue inhibitor of matrix-metalloproteinases

- EMT

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- EndoMT

Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

F.R. is on the Advisory Board for AbbVie and UCB, consultant to Samsung, Celgene, UCB and Roche and on the speakers bureau of AbbVie. G.L. has no competing interests.

References

- 1.Latella G, Rogler G, Bamias G, Breynaert C, Florholmen J, Pellino G, et al. Results of the 4th scientific workshop of the ECCO (I): pathophysiology of intestinal fibrosis in IBD. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2014;8(10):1147–65. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rieder F, Fiocchi C, Rogler G. Mechanisms, Management, and Treatment of Fibrosis in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):340–50 e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3•.Bettenworth D, Gustavsson A, Atreja A, Lopez R, Tysk C, van Assche G, et al. A Pooled Analysis of Efficacy, Safety, and Long-term Outcome of Endoscopic Balloon Dilation Therapy for Patients with Stricturing Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(1):133–42. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000988. The largest study to date evaluating safety and efficacy of endoscopic balloon dilation in Crohn's disease associated strictures. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rieder F, Zimmermann EM, Remzi FH, Sandborn WJ. Crohn's disease complicated by strictures: a systematic review. Gut. 2013;62(7):1072–84. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rieder F, Latella G, Magro F, Yuksel ES, Higgins PD, Di Sabatino A, et al. European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation Topical Review on Prediction, Diagnosis and Management of Fibrostenosing Crohn's Disease. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latella G, Di Gregorio J, Flati V, Rieder F, Lawrance IC. Mechanisms of initiation and progression of intestinal fibrosis in IBD. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2015;50(1):53–65. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.968863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke JP, Mulsow JJ, O'Keane C, Docherty NG, Watson RW, O'Connell PR. Fibrogenesis in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(2):439–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Chen W, Lu C, Hirota C, Iacucci M, Ghosh S, Gui X. Smooth Muscle Hyperplasia/Hypertrophy is the Most Prominent Histological Change in Crohn's Fibrostenosing Bowel Strictures: A Semiquantitative Analysis by Using a Novel Histological Grading Scheme. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2017;11(1):92–104. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw126. This investigation proposes that smooth muscle cell hyperplasia is a more prominent component to stricture formation compared to excessive deposition of extracellular matrix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon IO, Agrawal N, Goldblum JR, Fiocchi C, Rieder F. Fibrosis in ulcerative colitis: mechanisms, features, and consequences of a neglected problem. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(11):2198–206. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10•.Ippolito C, Colucci R, Segnani C, Errede M, Girolamo F, Virgintino D, et al. Fibrotic and Vascular Remodelling of Colonic Wall in Patients with Active Ulcerative Colitis. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2016;10(10):1194–204. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw076. Fibrosis is an important component of ulcerative colitis and can present in a transmural fashion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourgier C, Haydont V, Milliat F, François A, Holler V, Lasser P, et al. Inhibition of Rho kinase modulates radiation induced fibrogenic phenotype in intestinal smooth muscle cells through alteration of the cytoskeleton and connective tissue growth factor expression. Gut. 2005;54(3):336–43. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson LA, Rodansky ES, Haak AJ, Larsen SD, Neubig RR, Higgins PD. Novel Rho/MRTF/SRF Inhibitors Block Matrix-stiffness and TGF-beta-Induced Fibrogenesis in Human Colonic Myofibroblasts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(1):154–65. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000437615.98881.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrance IC, Rogler G, Bamias G, Breynaert C, Florholmen J, Pellino G, et al. Cellular and Molecular Mediators of Intestinal Fibrosis. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrance IC, Rogler G, Bamias G, Breynaert C, Florholmen J, Pellino G, et al. Cellular and molecular mediators of intestinal fibrosis. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazagova M, Wang L, Anfora AT, Wissmueller M, Lesley SA, Miyamoto Y, et al. Commensal microbiota is hepatoprotective and prevents liver fibrosis in mice. FASEB J. 2015;29(3):1043–55. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-259515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naftali T, Reshef L, Kovacs A, Porat R, Amir I, Konikoff FM, et al. Distinct Microbiotas are Associated with Ileum-Restricted and Colon-Involving Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(2):293–302. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17•.Yoo JH, Ho S, Tran DH, Cheng M, Bakirtzi K, Kukota Y, et al. Anti-fibrogenic effects of the anti-microbial peptide cathelicidin in murine colitis-associated fibrosis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1(1):55–74 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2014.08.001. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin can reverse intestinal fibrosis by direct inhibition of collagen synthesis in colonic fibroblasts. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashima S, Fujiya M, Konishi H, Ueno N, Inaba Y, Moriichi K, et al. Polyphosphate, an active molecule derived from probiotic Lactobacillus brevis, improves the fibrosis in murine colitis. Transl Res. 2015;166(2):163–75. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Yang J, Ding C, Dai X, Lv T, Xie T, Zhang T, et al. Soluble Dietary Fiber Ameliorates Radiation-Induced Intestinal Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Fibrosis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0148607116671101. The soluble dietary fiber pectin is protective against radiation induced fibrosis, which may be mediated by altered short chain free fatty acid concentration and reduced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Achiwa K, Ishigami M, Ishizu Y, Kuzuya T, Honda T, Hayashi K, et al. DSS colitis promotes tumorigenesis and fibrogenesis in a choline-deficient high-fat diet-induced NASH mouse model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;470(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tao Q, Wang B, Zheng Y, Jiang X, Pan Z, Ren J. Vitamin D prevents the intestinal fibrosis via induction of vitamin D receptor and inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta1/Smad3 pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(4):868–75. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22••.Lo BC, Gold MJ, Hughes MR, Antignano F, Valdez Y, Zaph C, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORα and group 3 innate lymphoid cells drive fibrosis in a mouse model of Crohn’s disease. Nat Immunol. 2016;1(3):8864. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaf8864. This investigation establishes RORα as a novel factor in fibrogenesis independent of eosinophils, STAT6 signaling and Th2 cytokine production. The mechanisms apears to involve type 3 ILCs, IL-17A and IL-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shea-Donohue T, Notari L, Sun R, Zhao A. Mechanisms of smooth muscle responses to inflammation. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2012;24(9):802–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair DG, Miller KG, Lourenssen SR, Blennerhassett MG. Inflammatory cytokines promote growth of intestinal smooth muscle cells by induced expression of PDGF-Rbeta. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2014;18(3):444–54. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hazelgrove KB, Flynn RS, Qiao LY, Grider JR, Kuemmerle JF. Endogenous IGF-I and alpha v beta3 integrin ligands regulate increased smooth muscle growth in TNBS-induced colitis. American journal of physiology. 2009;296(6):G1230–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90508.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flynn RS, Murthy KS, Grider JR, Kellum JM, Kuemmerle JF. Endogenous IGF-I and alphaVbeta3 integrin ligands regulate increased smooth muscle hyperplasia in stricturing Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(1):285–93. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li C, Vu K, Hazelgrove K, Kuemmerle JF. Increased IGF-IEc expression and mechano-growth factor production in intestinal muscle of fibrostenotic Crohn's disease and smooth muscle hypertrophy. American journal of physiology. 2015;309(11):G888–99. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00414.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Iness A, Yoon J, Grider JR, Murthy KS, Kellum JM, et al. Noncanonical STAT3 activation regulates excess TGF-beta1 and collagen I expression in muscle of stricturing Crohn's disease. J Immunol. 2015;194(7):3422–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Bruyn M, Vandooren J, Ugarte-Berzal E, Arijs I, Vermeire S, Opdenakker G. The molecular biology of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in inflammatory bowel diseases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;51(5):295–358. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2016.1199535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breynaert C, de Bruyn M, Arijs I, Cremer J, Martens E, Van Lommel L, et al. Genetic Deletion of Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1/TIMP-1 Alters Inflammation and Attenuates Fibrosis in Dextran Sodium Sulphate-induced Murine Models of Colitis. Journal of Crohn's & colitis. 2016;10(11):1336–50. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31•.Goffin L, Fagagnini S, Vicari A, Mamie C, Melhem H, Weder B, et al. Anti-MMP-9 Antibody: A Promising Therapeutic Strategy for Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Complications with Fibrosis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(9):2041–57. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000863. Despite common belief that inhibition of MMPs may promote fibrogenesis this study shows that blockade of MMP9 ameliorates intestinal fibrosis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells RG. The role of matrix stiffness in regulating cell behavior. Hepatology. 2008;47(4):1394–400. doi: 10.1002/hep.22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson LA, Rodansky ES, Sauder KL, Horowitz JC, Mih JD, Tschumperlin DJ, et al. Matrix stiffness corresponding to strictured bowel induces a fibrogenic response in human colonic fibroblasts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(5):891–903. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182813297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson LA, Rodansky ES, Haak AJ, Larsen SD, Neubig RR, Higgins PD. Novel Rho/MRTF/SRF inhibitors block matrix-stiffness and TGF-β-induced fibrogenesis in human colonic myofibroblasts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(1):154–65. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000437615.98881.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bettenworth D, Rieder F. Reversibility of Stricturing Crohn's Disease-Fact or Fiction? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(1):241–7. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto T, Fazio VW, Tekkis PP. Safety and efficacy of strictureplasty for Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(11):1968–86. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fazio VW, Tjandra JJ, Lavery IC, Church JM, Milsom JW, Oakley JR. Long-term follow-up of strictureplasty in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(4):355–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02053938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maconi G, Sampietro GM, Cristaldi M, Danelli PG, Russo A, Bianchi Porro G, et al. Preoperative characteristics and postoperative behavior of bowel wall on risk of recurrence after conservative surgery in Crohn's disease: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2001;233(3):345–52. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pellicoro A, Ramachandran P, Iredale JP, Fallowfield JA. Liver fibrosis and repair: immune regulation of wound healing in a solid organ. Nature reviews. 2014;14(3):181–94. doi: 10.1038/nri3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, Afdhal N, Sievert W, Jacobson IM, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381(9865):468–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.D'Ambrosio R, Aghemo A, Rumi MG, Ronchi G, Donato MF, Paradis V, et al. A morphometric and immunohistochemical study to assess the benefit of a sustained virological response in hepatitis C virus patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):532–43. doi: 10.1002/hep.25606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong F, Chou H, Fiel MI, Friedman SL. Antifibrotic activity of sorafenib in experimental hepatic fibrosis: refinement of inhibitory targets, dosing, and window of efficacy in vivo. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(1):257–64. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2325-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuo WL, Yu MC, Lee JF, Tsai CN, Chen TC, Chen MF. Imatinib mesylate improves liver regeneration and attenuates liver fibrogenesis in CCL4-treated mice. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16(2):361–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1764-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaker ME, Ghani A, Shiha GE, Ibrahim TM, Mehal WZ. Nilotinib induces apoptosis and autophagic cell death of activated hepatic stellate cells via inhibition of histone deacetylases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(8):1992–2003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi SS, Sicklick JK, Ma Q, Yang L, Huang J, Qi Y, et al. Sustained activation of Rac1 in hepatic stellate cells promotes liver injury and fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2006;44(5):1267–77. doi: 10.1002/hep.21375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46•.Wang M, Gong Q, Zhang J, Chen L, Zhang Z, Lu L, et al. Characterization of gene expression profiles in HBV-related liver fibrosis patients and identification of ITGBL1 as a key regulator of fibrogenesis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43446. doi: 10.1038/srep43446. This investigation combined an unbiased gene expression screen with a functional analysis identifying ITGBL1 as a novel regulator of fibrogenesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, Clay S, Partolina M, Vuthoori S, et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115(1):56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48••.Rantakari P, Patten DA, Valtonen J, Karikoski M, Gerke H, Dawes H, et al. Stabilin-1 expression defines a subset of macrophages that mediate tissue homeostasis and prevent fibrosis in chronic liver injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113(33):9298–303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604780113. Deficiency of stabilin-1 increased the expression of chemokine CCL3, exacerbated induction of liver fibrosis and delayed resolution during the recovery phase of experimental liver fibrosis. This is a novel pathway in which a failure to remove fibrogenic products of lipid peroxidation via a scavenger receptor drives fibrosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kagami S, Border WA, Miller DE, Noble NA. Angiotensin II stimulates extracellular matrix protein synthesis through induction of transforming growth factor-beta expression in rat glomerular mesangial cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1994;93(6):2431–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI117251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fogo AB. Progression and potential regression of glomerulosclerosis. Kidney international. 2001;59(2):804–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wengrower D, Zanninelli G, Latella G, Necozione S, Metanes I, Israeli E, et al. Losartan reduces trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colorectal fibrosis in rats. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(1):33–9. doi: 10.1155/2012/628268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puthawala K, Hadjiangelis N, Jacoby SC, Bayongan E, Zhao Z, Yang Z, et al. Inhibition of integrin alpha(v)beta6, an activator of latent transforming growth factor-beta, prevents radiation-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):82–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-806OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53•.Raghu G, Scholand MB, de Andrade J, Lancaster L, Mageto Y, Goldin J, et al. FG-3019 anti-connective tissue growth factor monoclonal antibody: results of an open-label clinical trial in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(5):1481–91. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01030-2015. Open label phase 2 trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of FG-3019 in subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. FG-3019 was safe and well-tolerated and changes in fibrosis were correlated with changed in pulmonary function. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ponticos M, Holmes AM, Shi-wen X, Leoni P, Khan K, Rajkumar VS, et al. Pivotal role of connective tissue growth factor in lung fibrosis: MAPK-dependent transcriptional activation of type I collagen. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(7):2142–55. doi: 10.1002/art.24620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55•.Yang R, Xu X, Li H, Chen J, Xiang X, Dong Z, et al. p53 induces miR199a-3p to suppress SOCS7 for STAT3 activation and renal fibrosis in UUO. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43409. doi: 10.1038/srep43409. This mechanistic study provides insight into the mechanisms of p53 in renal fibrosis in mice and humans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56••.Martinod K, Witsch T, Erpenbeck L, Savchenko A, Hayashi H, Cherpokova D, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase 4 promotes age-related organ fibrosis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2017;214(2):439–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160530. Aging promotes inflammation, fibrosis and decline in organ function. Peptidylarginine deimidase 4 (PAD4) is regulating the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), an important feature of acute inflammation. Martinod et al. found increased NETs with aging associated with fibrosis and this observation could be prevented by deletion of PAD4 in experimental models of cardiac fibrosis. This suggests that PAD4 regulates age-related organ fibrosis and could be a novel anti-fibrotic target. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hughes G, Toellner H, Morris H, Leonard C, Chaudhuri N. Real World Experiences: Pirfenidone and Nintedanib are Effective and Well Tolerated Treatments for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. J Clin Med. 2016;5(9) doi: 10.3390/jcm5090078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, Costabel U, Glassberg MK, Kardatzke D, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1760–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, Fagan EA, Glaspole I, Glassberg MK, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2083–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richeldi L, Costabel U, Selman M, Kim DS, Hansell DM, Nicholson AG, et al. Efficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1079–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2071–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62••.Liang J, Zhang Y, Xie T, Liu N, Chen H, Geng Y, et al. Hyaluronan and TLR4 promote surfactant-protein-C-positive alveolar progenitor cell renewal and prevent severe pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Nature medicine. 2016;22(11):1285–93. doi: 10.1038/nm.4192. This manuscript detected that the ECM component hyaluronan and TLR4 are critical in promoting type 2 alveolar epithelial cells, stem cells of the adult lung, augmenting repair of lung injury and limiting the amount of fibrosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cao Z, Lis R, Ginsberg M, Chavez D, Shido K, Rabbany SY, et al. Targeting of the pulmonary capillary vascular niche promotes lung alveolar repair and ameliorates fibrosis. Nature medicine. 2016;22(2):154–62. doi: 10.1038/nm.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64••.Rimola J, Planell N, Rodriguez S, Delgado S, Ordas I, Ramirez-Morros A, et al. Characterization of inflammation and fibrosis in Crohn's disease lesions by magnetic resonance imaging. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2015;110(3):432–40. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.424. Rimola et al. establish delayed enhancement MRI as a potential future method to separate inflammation in fibrosis in subjects with fibrostenosing Crohn's disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baumgart DC, Müller HP, Grittner U, Metzke D, Fischer A, Guckelberger O, et al. US-based Real-time Elastography for the Detection of Fibrotic Gut Tissue in Patients with Stricturing Crohn Disease. Radiology. 2015:141929. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14141929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fraquelli M, Branchi F, Cribiu FM, Orlando S, Casazza G, Magarotto A, et al. The Role of Ultrasound Elasticity Imaging in Predicting Ileal Fibrosis in Crohn's Disease Patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(11):2605–12. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dillman JR, Swanson SD, Johnson LA, Moons DS, Adler J, Stidham RW, et al. Comparison of noncontrast MRI magnetization transfer and T2 -Weighted signal intensity ratios for detection of bowel wall fibrosis in a Crohn's disease animal model. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(3):801–10. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pazahr S, Blume I, Frei P, Chuck N, Nanz D, Rogler G, et al. Magnetization transfer for the assessment of bowel fibrosis in patients with Crohn's disease: initial experience. MAGMA. 2013;26(3):291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10334-012-0355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wolff SD, Chesnick S, Frank JA, Lim KO, Balaban RS. Magnetization transfer contrast: MR imaging of the knee. Radiology. 1991;179(3):623–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.3.2027963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]