Abstract

We explored the process of implementing an HIV testing program at an intimate partner violence (IPV) service agency from the client and provider perspectives. A qualitative descriptive approach was used wherein semi-structured interviews were conducted with 19 key informants (i.e., women with a history of IPV, HIV service providers, IPV service providers). Interviews focused on facilitators and barriers to HIV testing implementation, the decision-making process during HIV testing, and support needs. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. The text of the interviews was analyzed using directed content analysis. Unique factors were found to influence HIV testing in victims of IPV including potential for re-traumatization, readiness for testing, competing priorities, and the influence of children. The results provided important information that can be used to improve the implementation of HIV testing, tailoring processes so they are more trauma-informed, and better support individuals with a history of IPV.

Keywords: domestic violence, HIV, HIV screening

Intimate partner violence (IPV), defined as physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, or psychological aggression by a current or former intimate partner, is a critical public health concern (Breiding et al., 2014). Nearly one-third of U.S. women have reported being raped and/or physically assaulted by a current or past partner (Black et al., 2011). Studies have indicated important relationships between IPV and HIV infection (Campbell et al., 2008; Li et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2014). In the United States, women living with HIV infection experience IPV at rates higher than the general population (Gielen et al., 2007). Many of the dynamics involved in situations of IPV place victims at increased risk of acquiring HIV, including forced sex, sexual risk taking behaviors, decreased ability to negotiate safer sex practices, higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and abuse-related compromised immunity (Campbell et al., 2008; Maman, Campbell, Sweat, & Gielen, 2000).

The importance of this issue has been highlighted in recent years, not only through a growing body of research, but also through several initiatives enacted at both the national and international levels. These include the Unite with Women program of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS, 2014) and the Interagency Federal Working Group established by the White House to explore and provide recommendations on the intersection of HIV, violence against women and girls, and gender-related health disparities (White House Office of the Press Secretary, 2012). Most of these initiatives have called for increased efforts to integrate services for HIV and IPV, including increased HIV testing for this high-risk population. In 2013, the Violence Against Women Act (Public Law 113-4) was reauthorized by the U.S. Congress and included, for the first time, a provision for HIV testing, counseling, and post-exposure prophylaxis for victims of IPV and sexual assault (Office on Violence Against Women Department of Justice, 2013).

Current guidance describes the HIV testing process as “a collection of activities designed to increase clients’ knowledge of their HIV status, encourage and support risk reduction, and secure needed referrals for appropriate services” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009, p. 1). During this process, many decisions have to be made, such as whether or not to have a test, type of test to use, partner notification, risk reduction strategies, and follow-up services, many of which rely heavily on the preferences of the client (i.e., preference-sensitive decisions). In addition, when facing difficult health-related decisions, clients often face a degree of decisional conflict, or uncertainty about which course of action to take. The resolution of this conflict is greatly influenced by a client’s decision-making preferences and decision supports.

HIV counseling provides an important opportunity to guide individuals through this decision-making process. Researchers have noted that counseling strategies should go farther than just helping clients make decisions about whether or not to have an HIV test; they should also include elements of empowerment, ongoing psychological and emotional support, and assistance with accessing resources (Doull et al., 2006). The decision-making preferences and decision support needs of individuals undergoing HIV testing, however, are likely to differ for someone with a history of victimization and for whom issues such as safety, loss of autonomy, isolation, and chronic stress may be of particular concern. Research is needed to better understand the unique preferences and support needs of individuals with a history of IPV during the HIV testing process.

Studies have identified numerous barriers to HIV testing including fear, stigma, lack of knowledge about risk factors, treatment options and costs, and difficulty accessing/navigating the health care system (Evangeli, Pady, & Wroe, 2016; Messer et al., 2013; Schwarcz et al., 2011). Additional barriers exist for individuals with a history of IPV such as fear of subsequent violence from partners, social isolation that further limits the individual’s ability to access care, and a lack of knowledge on the part of many providers to identify individuals with a history of victimization and link them to appropriate services, including HIV testing (Draucker et al., 2015; Maher et al., 2000; Rountree, 2010). In order to reduce barriers to HIV testing for victims of IPV, it is crucial that HIV testing procedures be developed and conducted in a manner that is consistent with the unique needs and preferences of those affected by IPV.

Integrating HIV services into established IPV programs may be an important strategy for increasing the availability of HIV services that are sensitive to IPV victim needs. This is important because victims of IPV often require numerous services (e.g., social, legal, housing) and can experience challenges coordinating service needs. Providing multiple services at the same location can reduce these challenges and increase the likelihood of engaging in services. Increasing access to testing can also raise awareness of HIV risk, which can facilitate subsequent testing and engagement in risk reduction strategies such as pre-exposure prophylaxis medication. Recent qualitative work has indicated that providing HIV testing and counseling services within IPV service agencies is acceptable to clients (Draucker et al., 2015). To date, however, most efforts in this area have focused on integrating IPV services into established HIV testing/treatment programs and, thus, more knowledge is needed about how HIV services can be integrated into established IPV programs (e.g., social services agencies).

The purpose of our study was to explore the process of implementing an HIV testing program at an IPV service agency from the client and provider perspectives. Specifically, we sought to better understand barriers and facilitators to the implementation of an HIV testing program in a non-traditional setting (i.e., a social service agency) that targeted a high-risk population (i.e., individuals with a history of IPV). This knowledge can help improve the provision of HIV testing services to individuals with a history of IPV, which is critical given the intersection between HIV and IPV.

Methods

Parent Study

The study reported here was conducted as an adjunct to an already-established NIH-funded study (P60MD002266) examining disparities in HIV, STIs, and testing in victims of IPV. The purpose of the parent study was to explore predictors of HIV, STI, and HIV/STI testing within a racially and ethnically diverse sample of victims of IPV and to identify culturally-informed strategies to potentially increase HIV/STI testing for this population. As part of the parent study, HIV testing was provided to clients at a family justice center located in a large, urban metropolitan area in the southeastern United States. The center provided coordinated, comprehensive, and compassionate services to victims of IPV, sexual violence, and human trafficking; their children; and the general community. The need for HIV services at the center was identified through prior community-based participatory research conducted by Gonzalez-Guarda, Cummings, Becerra, Fernandez, and Mesa (2013). The study reported here sought to complement and extend the work being done by the parent study by examining the barriers, facilitators, and decision-making processes involved as part of the HIV testing program from the perspectives of both providers and clients.

Study Design

A qualitative descriptive research design was used to guide the conduct of the study. Qualitative descriptive studies entail the presentation of the facts of the case in everyday language. Researchers using this method seek descriptive and interpretive validity, by staying close to their data (Sandelowski, 2000). Qualitative description is particularly amenable to obtaining straight and largely unadorned answers to questions of special relevance to practitioners and policy makers. In a naturalistic study there is no pre-selection of variables to study, no manipulation of variables, and no a priori commitment to any one theoretical view of a target phenomenon (Sandelowski, 2000).

Sample

Participants for our study included key informants who could provide valuable insight into the implementation and decision-making processes about HIV testing by victims of IPV. Key informants included women with a history of IPV, IPV service providers (e.g., advocates), and HIV service providers. Participants were recruited from the pool of participants in the parent study, the family justice center and its affiliated agencies, and other HIV testing sites in the local area. To be eligible, individuals had to be 18 years of age and older. In addition, the following criteria had to be met. Women with a history of IPV participants had to be (a) female victims of IPV seeking services at the family justice center, (b) a participant in the parent study, (c) eligible to receive and offered an HIV test as part of the parent study, and (d) purposively selected, so that 50% of those enrolled had received an HIV test as part of the parent study and the other 50% did not want to be tested. IPV service provider participants had to be (a) employed by the family justice center or an affiliated agency in which the primary mission of the agency was to provide services to victims of IPV, (b) certified as an HIV tester and counselor, and (c) experienced in providing HIV testing services to victims of IPV. HIV service providers had to be (a) employed by a registered HIV testing center in the local area in which the primary mission of the agency was not to provide services to victims of IPV, (b) certified as an HIV tester and counselor, and (c) experienced in providing HIV testing services to victims of IPV.

Eligibility was assessed in person or over the phone using a screening tool. If eligibility was met, a study team member provided further detail on the purpose of the study, assessed continued interest, and scheduled a time for an interview.

Data Collection

The study was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewer reviewed the informed consent form and interview procedures with the participant.

After obtaining consent, basic demographic data were collected from participants either through review of the client intake form (victims of IPV) or through a brief questionnaire (IPV and HIV providers). Semi-structured, qualitative interviews were conducted face-to-face in the participant’s preferred language (English or Spanish). The interviews focused on facilitators and barriers to the HIV testing implementation process, the decision-making process during HIV testing, and decision support needs. An interview guide was developed for the study, based partly on the Decisional Needs Assessment Interview Guide developed by Jacobsen, O’Connor, and Stacey (2013). All interviews were conducted in a private location and audio recorded; the interviews lasted approximately 1 hour. Recruitment continued until interviewers determined that data saturation occurred. Participants received $50 compensation for their time.

Data Analysis

Demographic data were analyzed through descriptive statistics. Directed content analysis was used to examine the interview data. Through this process, data were examined under three major categories: (a) the decision-making process during HIV testing, (b) facilitators and barriers to HIV testing, and (c) support and resource needs. Each transcribed interview was read in its entirety in order to get a sense of its essential features, underlining key statements and writing a brief abstract of the distinctive elements (Sandalowski, 1995). The data were examined and coded using in-vivo codes that emerged from the data (Marshall & Rossman, 2015). Codes were then grouped into conceptual categories and themes generated from the data. A codebook was maintained to detail the codes and definitions. An audit trail of the coding process was kept as a running record of procedures for data collection and analytic strategies (Marshall & Rossman, 2015). Credibility of the data and analysis were addressed through a coding audit in which all of the text was double coded (i.e., coded independently by two researchers) and compared for consistency. Discrepancies were reviewed by both coders until consensus in major themes was achieved.

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. A total of 19 individuals participated: 10 women with a history of IPV, 5 HIV service providers, and 4 IPV service providers. Participants were from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds with 100% (n = 10) of women with a history of IPV and 77.8% (n = 7) of service providers identifying as Black or Hispanic/Latino, many of whom were born outside of the United States. Ages ranged from 24 to 50 years for victims of IPV and 26 to 53 years for service providers (mean 34.4 [SD = 10.5] and 38.1 [SD = 8.9], respectively). Most women with a history of IPV had received an HIV test at some point in their lives (n = 9; 90.0%). The majority of service providers had been a certified HIV tester and counselor for more than 1 year (n = 5; 55.6%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Women with a History of IPV (n = 10) | Service Providers (n = 9) | |

| Age | 34.4 (10.5) | 38.1 (8.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2 (20.0) | 1 (11.1) |

| White, Hispanic | 8 (80.0) | 6 (66.7) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) |

| Preferred Language | ||

| English | 5 (50.0) | 9 (100) |

| Spanish | 5 (50.0) | 0 (0) |

| Place of Birth | ||

| United States | 3 (30.0) | 5 (55.6) |

| Outside of the United States | 7 (70.0) | 4 (44.4) |

| Ever Received an HIV Test | ||

| Yes | 9 (90.0) | N/A |

| No | 1 (10.0) | N/A |

| Time of initial HIV testing certification | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Within the past year | N/A | 4 (44.4) |

| 1–5 years ago | N/A | 2 (22.2) |

| More than 5 years ago | N/A | 3 (33.3) |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

Decision-Making Process During HIV Testing

Women with a history of IPV

Participants discussed the decision-making process one goes through during HIV testing. For women with a history of IPV, this discussion centered on feelings about the process. They were often concerned with the comfort and convenience of the testing process. Those who received HIV testing at the family justice center provided a lot of detail about the process, stating it was comfortable and warm because it was not a hospital or clinic. As stated by one participant,

Honestly, I think that at a clinic it would be too cold – like, you go and pay for a service and have it done. And here, I don’t know – her service was like giving me care and protection. Do you understand? She made me feel important.

Feeling supported by the HIV tester and counselor was also discussed as an important part of the process as indicated through the following quote:

The person who did it was great. She didn’t make me feel like if I was in a hospital. She made me feel like it’s normal. She made everything feel casual and then on top of that she informed me and gave me stories to make me feel comfortable of doing this.

Participants appreciated the convenience of having HIV testing services at the family justice center and not needing to go somewhere else. One participant stated,

I was actually really, really relieved that they did the testing here. I was. Because I haven’t done it in such a long time, and then the lady asked me. I was like, ‘Yes. Finally. I don’t have to go anywhere else.’ I could just do it.

Service providers

Service providers discussed HIV testing in more technical terms. They described it as a structured process that included providing information and education to clients (e.g., risk factors and window period); informing about privacy, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of testing; gathering data; and the process of conducting the test (usually rapid testing), including an explanation of the results. Service providers also discussed challenges of the testing process including funding, length of certification training, and extensiveness of data collection. IPV service providers discussed additional challenges when collecting data from victims of IPV. Specifically, they felt many of the risk behavior questions they were required to ask by the health department were sensitive for this population and might even lead to re-victimization. For example, one provider stated,

The clients are not very comfortable with the questions that we need to ask…sometimes I feel like I have to somehow sugar-coat it or try to see how I can ask her those personal questions, intimate questions about sex. And we’re dealing with someone that could be in crisis or is dealing with the abuse already, so, I find it that they’re not comfortable with us asking them those questions; having to recall past abuse.

Facilitators and Barriers to HIV Testing

Women with a history of IPV

Women with a history of IPV discussed many factors that influenced their decisions to get an HIV test. Common reasons for getting a test included peace of mind, pregnancy, knowing someone with HIV, and risk history. Infidelity was a major concern when discussing potential risk. Many women knew or suspected that their partners had multiple sex partners during the time they were with them. In describing why she decided to get an HIV test, one participant stated,

The aggressor is my husband. I’m still in the process of divorce; it hasn’t ended. So after we married, a few months later, when we had a lot of problems, he confessed that he had had sexual relations with his ex-sister-in-law – the sister of his other wife before me.

Children were also discussed as an influencer of the decision to get an HIV test, and often reported as the most important consideration. Most stated it was important to know their HIV status to better provide for their children; however, some felt that knowing their status could have a negative impact on their children. For example, one participant stated, “I have a child and I don’t want to imagine someone telling me I have a mortal illness because I wouldn’t know what my life and my son’s would be like from that moment onwards.” Fear, both in general and specifically for one’s children, and the stress of knowing one’s status were the primary reasons why participants said they would not get tested or had not been tested in the past.

Despite these barriers, most stated that the pros of testing outweighed the cons. When asked about the pros of testing, participants generally stated it was “good to know.” They also said it was important because if you were positive, you could get early access to treatment, reduce transmission to others, and improve your health and quality of life. The decision to get tested, despite being afraid was indicated by one woman,

Well, it wasn’t easy – honestly, I was very afraid to. I was afraid because you don’t want to find out about something like that, but it’s worse to live with doubts, or to find out when it’s too late, so that’s why I had to gain courage and do it.

Service providers

In describing facilitators to HIV testing, service providers highlighted their overall goals for facilitating the process. One important goal involved providing appropriate education to clients. The education focused on helping the women develop communication skills with their partners, and learn about the HIV disease process and the HIV testing window, including the need for retesting. Another goal was related to identifying a client’s risk for HIV. This involved having the client acknowledge her risk and determining what was important for her at that moment. Understanding the client’s motivating factors was identified as important for developing a tailored testing and risk reduction strategy. Providers also identified linking clients to resources as an important goal, primarily focused on mental health and health care services, and services for HIV retesting. Finally, providers discussed the importance of providing a confidential and supportive environment in facilitating HIV testing. Many of these goals were illustrated in the following quote,

So, our departmental goal is to educate folks, to get them tested, to give them information about how often they should be getting tested, sometimes how to talk to their partners about getting tested, and then also to make referrals to other services that those community members might need.

Providers also recognized the many pros to HIV testing, while at the same time, they acknowledged the barriers clients faced in deciding to get tested. Pros of testing primarily focused on gaining early access to treatment for those who were diagnosed with HIV and education about prevention for those who were not. As one participant stated,

I firmly believe that a negative test is one of the best tools to stay negative. So, if you’ve done a series of tests and they’re negative, you can stay negative by doing proper things like reducing partners or putting on condoms. Obviously, if you’ve tested positive for something then getting a linkage to the medical care is obviously another pro of testing.

General barriers to testing focused on client attitudes about HIV. Providers stated that “people don’t like to talk about it,” “don’t know how to approach the topic,” and that offering testing “could be offensive to the patient.”

Providers also acknowledged that victims of IPV had unique needs and challenges related to HIV and HIV testing. This viewpoint was more prominent for IPV service providers. Providers noted that victims were often dealing with many competing priorities, particularly when leaving an abusive relationship. These priorities included maintaining safety, securing housing, obtaining child custody and other legal services (e.g., immigration), and working through mental health issues. HIV testing was often not high on the list of priorities and might, in fact, create additional difficulties if the result were positive. Providers also stated that victims often felt stigmatized by their abuse history and finding out they had HIV infection could add another layer of stigma. Providers stressed difficulties when counseling victims of IPV about risk reduction strategies because often they were not responsible for the situations that placed them at risk for HIV (e.g., forced-sex and/or inability to negotiate condom use with an abusive partner). Finally, providers noted challenges in following up with clients for re-testing because they often did not have stable or safe housing or forms of communication (e.g., phone, email). In describing the challenges victims of IPV faced, one participant stated,

Well, for intimate partner violence, it’s a little different. Because what their needs are, are totally different than someone who is not going through their situation. This person may be worrying about where they’re gonna’ live, where their kid’s gonna’ live, their family getting threatened by the person. It’s just so much other things that’s on that person’s mind that is going through this intimate partner violence, that they may put HIV, STIs, AIDS, on the back burner. They may put it on a back burner, because that’s not a priority to them.

Support and Resource Needs

Women with a history of IPV

Women with a history of IPV provided several recommendations for improving feelings of support and resources provided during the HIV testing process. They stressed the importance of feeling supported throughout the testing process and not feeling like it was just “an ordinary medical procedure.” Participants who received HIV testing at the family justice center reiterated that they felt very supported by staff. They believed it was better to have testing done at an IPV service agency because it was a safer, more confidential location and staff were more sensitive to their particular situations.

Participants also expressed a desire for more information and better resources related to HIV and HIV testing. There were mixed reports on the availability of HIV testing in the local area; some said they saw HIV testing everywhere and others said they never saw it. Media and advertising was cited as the primary source for information about testing, but they did not believe this was enough to encourage people to get tested. Rather, participants stated that a personal connection with someone (e.g., service provider, friend, family member) was needed to facilitate actual testing. Most participants said they were given information during the HIV testing process, but wanted more, particularly related to the HIV disease process, how the test worked, and what would happen if the test were positive. As one participant stated,

People already know that if you had sex unprotected, you can get HIV. But me, I just want to know more about HIV. How does it flow? Some more side effects that it will cause, or how else that you can get it. What happens if you are positive? It’s always good to know more information. It’s always good to know that. I would actually sit down and I would actually pay attention to that because I want to know.

Service providers

Providers discussed the importance of providing holistic services to meet the needs of clients, both in general, and specifically for those with a history of IPV. Holistic services were described as including not only HIV testing but additional support and education services. As illustrated by one provider,

So, we find that people need more than just HIV testing, and I think that we need to be able to at least provide them with a referral, or some more services. And, I think we’ll be doing okay, because a lot of places, you have to go over here for this, go over there for that. There’s nowhere where you can just come in and do everything.

To provide clients with proper support, providers stated that HIV testing must be conducted in a setting that is comfortable for the client, that staff should be trained to provide testing in a trauma-informed manner, and emotional support needed to be provided for clients with positive test results. Providers also acknowledged that clients often have needs outside the scope of HIV testing, such as other health or IPV-related concerns. Providers emphasized the importance of establishing interagency partnerships to improve the ability to provide or refer clients to these additional services. In discussing additional support needs, one participant said,

I think one of the things that we’re always looking for is different and better trainings to help our counselors be able to really look at the client who comes in and say, “Okay, I know what to do in this situation.” We’ve had trainings on [IPV], but I wouldn’t say that they’ve been super effective, and we do have a clear agency protocol about what that’s supposed to look like if someone says that. But in terms of – in particular with domestic violence or intimate partner violence – if someone were to come in and say that, I don’t know that my counselors would know exactly what to do…It’s also just knowing what other community resources are out there, and, again, addressing it within our agency protocol and making sure that we have something on our end that says, “If this comes up, here are some red flags. Here’s what you do.”

Education needs identified by providers included education about HIV risks, misperceptions, and the HIV testing process. Finally, providers discussed ways to improve the process of HIV testing, particularly for victims of IPV. These included increasing the availability of testing at locations where victims often accessed other services (e.g., courts, shelters) and consolidating the collection of data on sexual risk factors, as victims often have to provide this information numerous times when seeking IPV-related services and recalling traumatic experiences can be re-victimizing. As described by one participant,

We need to be sensible, sensitive, and competent in terms of knowing the issue and the community that you’re providing that service to. We need to evaluate clients’ needs and clients’ state of mind in traumatization processes before just jumping to do it. Because it can be so re-traumatizing. So, re-victimization can happen easily. And it can scare the person out of it. So, it requires – in this area, requires some sort of specific conversation and the specific knowledge that I don’t think is in place. I don’t think that it’s something that is offered.

Discussion

Our study provides insight on the HIV testing process from the perspectives of women with a history of IPV and providers with experience providing HIV testing to victims of IPV. Increased recognition of the intersection between HIV and IPV has led to numerous calls to improve the delivery of HIV services to be more responsive to those with a history of trauma (Sales, Swartzendruber, & Phillips, 2016). Results from our study highlight aspects of the testing process that may be unique for victims of IPV and have implications for improving the quality of HIV testing in this population.

The concept of re-traumatization is a unique concern for those with a history of trauma such as IPV. Re-traumatization can occur when an individual re-experiences traumatic stress as a result of being in a situation that is similar to prior traumatic experiences (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). Participants in our study noted the potential for re-traumatization during HIV testing, particularly when asking HIV risk behavior questions, and the client’s need to feel supported through the testing process. Other unique factors included concerns about readiness for testing when faced with competing priorities and the role of children in influencing testing decisions.

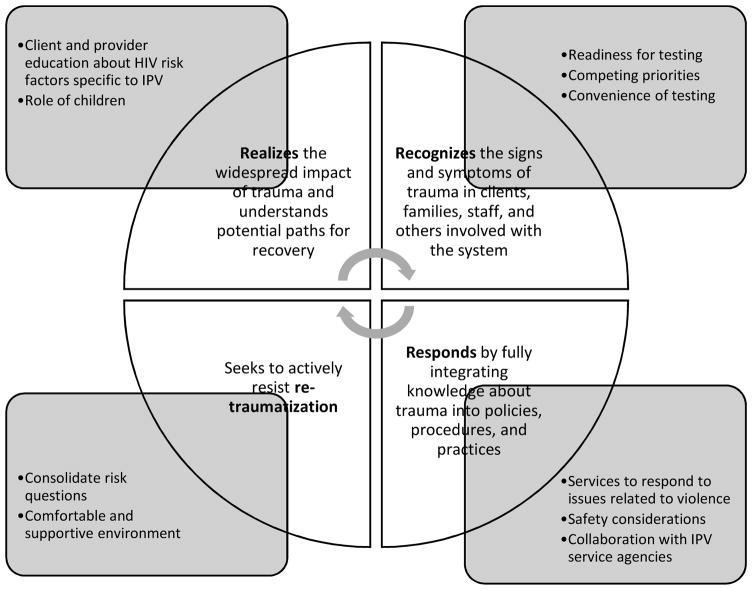

Many of the issues highlighted in the interviews can be viewed from a trauma-informed perspective. Trauma-informed services are based on an understanding of the vulnerabilities individuals with a history of trauma may have and are designed to be supportive and avoid re-traumatization (SAMHSA, 2015). According to SAMHSA (2015), “A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed:

Realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery;

Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system;

Responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and

Seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.” (¶ 2)

The results of our study point to several ways in which HIV testing can be tailored to meet the characteristics of trauma-informed programs. Figure 1 summarizes how the recommendations provided by our participants addressed each of the four characteristics of trauma-informed programing described by SAMHSA. We expand on the criteria below, with specific suggestions for how IPV and service agencies can tailor HIV testing to better address the needs of those affected by IPV. These recommendations are not meant to be an exhaustive list of components needed for effective trauma-informed HIV testing, but rather provide considerations for future intervention development.

Figure 1.

Recommendations from study findings for tailoring HIV testing programs based on SAMHSA’s trauma-informed approach (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2015).

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

Realization of Trauma Impact and Paths for Recovery

Experiences of trauma, such as IPV, can have numerous impacts on HIV risk, testing decisions, and paths for recovery (Draucker et al., 2015; Rountree, 2010; Sales et al., 2016). Providers in our study indicated that there was a need for improved awareness in both clients and providers that the experience of IPV increased an individual’s risk for acquiring HIV. They also noted a need for more education about the mechanisms through which increased risk occurs. In our study, women with a history of IPV seldom discussed HIV risk in relation to IPV. This may have been, in part, due to a lack of awareness about HIV risk. Research has shown a link between risk knowledge and HIV-testing behavior (Evangeli et al., 2016), but studies are needed to examine how risk knowledge specific to IPV impacts HIV testing in this population. Futures Without Violence provides several free resources about the intersection of HIV and IPV targeting both patients and providers (Futures Without Violence, 2017). These include pocket safety cards for patients and training modules for providers. Increasing the availability of these types of resources in IPV and HIV service agencies can support programs aimed at increasing awareness about HIV risk for victims of IPV.

The role of children was identified as a particularly important consideration when making decisions about HIV testing and may impact paths for recovery in individuals with a history of violence. Some participants were motivated to get tested because of their children while, for others, children were a reason to not get tested. Providers should be aware of this duality when discussing HIV testing options with clients in order to tailor conversations based on a client’s particular motivations regarding children.

Recognition of Signs and Symptoms of Trauma

To provide trauma-informed HIV services, it is also critical for service providers to recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma. This includes how signs and symptoms may impact receipt of services. Results of our study illustrate how signs and symptoms of IPV can impact receipt of HIV testing services. For example, providers particularly noted how the experiences of IPV can impact an individual’s readiness to take an HIV test. Individuals with a history of trauma, such as IPV, often experience mental health consequences that may impact how they approach HIV testing. Women with a history of IPV may also have many competing priorities, which can overshadow the need for HIV testing. Interventions are needed to help providers recognize how these signs and symptoms impact HIV testing, including tools for assessing readiness and competing priorities in individuals with a history of trauma.

Finally, the convenience of HIV testing was identified as an important factor in facilitating HIV testing. Individuals who have experienced IPV often require services from multiple criminal justice, health, and social service agencies. To address their high service needs, the U.S. Government initiated the President’s Family Justice Center Initiative in 2003 (Office on Violence Against Women, 2007). The initiative created specialized, co-located, multi-disciplinary service centers (one stop shops) for victims of family violence and their children throughout the United States. Family justice centers and other IPV service agencies are well placed to integrate a trauma-informed approach to HIV testing due to the nature of their work.

Response Through the Integration of Trauma Knowledge

The integration of trauma knowledge in policies, procedures, and practices is necessary for organizations to effectively respond to those affected by trauma, such as victims of IPV. Results from our study indicated that issues related to violence often arise when implementing HIV testing in those with a history of IPV. Having access to services that allow providers to appropriately respond to issues related to IPV is needed in order to provide holistic services for this population. Additionally, the integration of trauma knowledge into testing settings should include a focus on how the safety of victims will be assured. Concerns about safety can present a barrier to testing. For HIV testing centers, developing strong collaborations with local IPV service agencies can be an effective strategy for providing access to trauma services and beginning the process of integrating trauma knowledge into current practices.

Active Resistance of Re-Traumatization

A common sentiment in the study interviews was a desire for testing to be conducted in a comfortable and supportive environment. Although this is likely a desire of most individuals receiving HIV testing, it is particularly important for those with a history of trauma due to the potential for re-traumatization. Individuals with a history of IPV can experience re-traumatization through services that are unsupportive and insensitive to their experiences.

Our participants also expressed concern about risk behavior questions asked during HIV testing. The HIV testing process includes questions about an individual’s sexual behaviors in order to assess risk for HIV. For an individual who has experienced IPV, these questions are often related to victimization experiences. Re-traumatization may occur due to a recall of traumatic experiences and the fact that victims of IPV are required to answer sensitive questions about sexual activities multiple times when accessing IPV-related services (e.g., legal, social, health). Ensuring that providers are sensitive to the fact that individuals with a history of IPV may engage in HIV risk behaviors as part of their victimization and that providers tailor risk reduction messaging accordingly, may reduce the potential for re-traumatization. In addition, service agencies should explore ways to consolidate sexual-risk questions to minimize the number of times clients have to answer these sensitive questions.

Limitations

In our study, individuals with a history of IPV were recruited from a domestic violence service agency. Nine of our 10 participants who had experienced IPV had received an HIV test at some point in their lives. Views on HIV testing may differ for those who have not engaged in HIV testing or help-seeking for IPV. Some participants were recruited from the parent study, which may have indicated a higher level of commitment to HIV testing and/or research. In addition, the interview guide we used was based, in part, on the Decisional Needs Assessment Interview Guide to elicit information related to decisions about disclosure (Jacobsen et al., 2013). The structure of the interview guide may have influenced responses in unintended ways.

Conclusions

Numerous factors influence an individual’s likelihood of engaging in HIV testing; experiences of IPV present unique considerations that can influence this decision-making process. Recognizing the factors that influence a client’s willingness to test for HIV as it relates to IPV is critical for improving HIV prevention in this population. Providers must recognize how factors related to IPV influence a client’s decision-making regarding HIV testing and adopt a trauma-informed approach when providing HIV testing services. Creating partnerships with HIV and IPV service agencies is a critical step in developing these approaches.

Key Considerations.

Individuals who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) are at increased risk of acquiring HIV; at the same time, they experience barriers to receiving HIV testing.

A better understanding of the HIV testing process from the perspective of victims of IPV and those who work with them may help reduce barriers and, ultimately, lead to higher rates of HIV testing and better quality services for this high-risk population.

Unique factors influence HIV testing for victims of IPV, including potential for re-traumatization, readiness for testing, competing priorities, and the influence of children.

Tailoring HIV testing processes so they are more trauma-informed can better support individuals with a history of IPV.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Prevention Implementation Methodology (Ce-PIM) for Drug Abuse and Sexual Risk Behavior Pilot Study Award (NIDA & OBSSR, P30-DA027828, IS-03-09) and the Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro (NIMHD, P60MD002266). We would like to acknowledge Dawn Stacey, RN, PhD, CON(C), for her consultation on the design and methods of this study. We would also like to acknowledge the Coordinated Victim Assistance Center of Miami-Dade County for their assistance in participant recruitment and our participants for sharing their stories.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jessica R. Williams, Assistant Professor, University of Miami School of Nursing and Health Studies, Coral Gables, Florida, USA.

Rosa M. Gonzalez-Guarda, Associate Professor, Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Vanessa Ilias, BSN Student, University of Miami School of Nursing and Health Studies, Coral Gables, Florida, USA.

References

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, … Stevens M. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. 2011 Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_report2010-a.pdf.

- Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Basile KC, Walters ML, Chen J, Merrick MT. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization--National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports Surveillence Summaries. 2014;63(8):1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: A review. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2008;15(4):221–231. doi: 10.1080/17457300802423224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV counseling, testing, and referral. 2009 Retrieved from https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/docs/default-source/public-health-strategies-docs/HIV_CTR_Procedural_Guide_8-09.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- Doull M, O’Connor A, Jacobsen MJ, Robinson V, Cook L, Nyamai-Kisia C, Tugwell P. Investigating the decision-making needs of HIV-positive women in Africa using the Ottawa Decision-Support Framework: Knowledge gaps and opportunities for intervention. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;63(3):279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draucker CB, Johnson DM, Johnson-Quay NL, Kadeba MT, Mazurczyk J, Zlotnick C. Rapid HIV testing and counseling for residents in domestic violence shelters. Women’s Health. 2015;55(3):334–352. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.996726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangeli M, Pady K, Wroe AL. Which psychological factors are related to HIV testing? A quantitative systematic review of global studies. AIDS & Behavior. 2016;20(4):880–918. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1246-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futures Without Violence. HIV and IPV resources. 2017 Retrieved from https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/?s=HIV.

- Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: Intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(2):178–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Cummings AM, Becerra M, Fernandez MC, Mesa I. Needs and preferences for the prevention of intimate partner violence among Hispanics: A community’s perspective. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2013;34(4):221–235. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen MJ, O’Connor AM, Stacey D. Decisional needs assessment in populations. A workbook for assessing patients’ and practitioners’ decision making needs. 2013 Retrieved from https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/implement/Population_Needs.pdf.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Unite with women - Unite against violence and HIV. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/20140312_JC2602_UniteWithWomen.

- Li Y, Marshall CM, Rees HC, Nunez A, Ezeanolue EE, Ehiri JE. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17:18845. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher JE, Peterson J, Hastings K, Dahlberg LL, Seals B, Shelley G, Kamb ML. Partner violence, partner notification, and women’s decisions to have an HIV test. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2000;25(3):276–282. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200011010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat MD, Gielen AC. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(4):459–478. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing qualitative research. 6. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Messer LC, Quinlivan EB, Parnell H, Roytburd K, Adimora AA, Bowditch N, DeSousa N. Barriers and facilitators to testing, treatment entry, and engagement in care by HIV-positive women of color. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2013;27(7):398–407. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office on Violence Against Women. The President’s family justice center initiative, best practices. 2007 Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/archive/ovw/docs/family_justice_center_overview_12_07.pdf.

- Office on Violence Against Women Department of Justice. VAWA 2013 summary: Changes to OVW-administered grant programs. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/ovw/legacy/2014/06/16/VAWA-2013-grant-programs-summary.pdf.

- Phillips DY, Walsh B, Bullion JW, Reid PV, Bacon K, Okoro N. The intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV in U.S. women: A review. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2014;25(Suppl 1):S36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree MA. HIV/AIDS risk reduction intervention for women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2010;38(2):207–216. doi: 10.1007/s10615-008-0183-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Swartzendruber A, Phillips AL. Trauma-informed HIV prevention and treatment. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2016;13(6):374–382. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0337-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandalowski M. Focus on qualitative methods qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin. Research in Nursing and Health. 1995;18:371–375. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz S, Richards TA, Frank H, Wenzel C, Hsu LC, Chin CS, … Dilley J. Identifying barriers to HIV testing: Personal and contextual factors associated with late HIV testing. AIDS Care. 2011;23(7):892–900. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.534436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 57. 2014 Retrieved from http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4816/SMA14-4816.pdf. [PubMed]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

- White House Office of the Press Secretary. Presidential Memorandum -- Establishing a working group on the intersection of HIV/AIDS, violence against women and girls, and gender-related health disparities. 2012 Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2012/03/30/presidential-memorandum-establishing-working-group-intersection-hivaids-