Abstract

Background

In an effort to improve quality and reduce costs, payments are being increasingly tied to value through alternative payment models, such as episode-based payments. The objective of this study was to better understand the pattern and variation in outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries receiving lower extremity joint replacement over 90-day episodes of care.

Methods

Observed rates of mortality, complications, and readmissions were calculated over 90-day episodes of care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who received elective knee replacement and elective or non-elective hip replacement procedures in 2013–2014 (N=640,021). Post-acute care utilization of skilled nursing and inpatient rehabilitation facilities was collected from Medicare files.

Results

Mortality rates over 90-days were 0.4% (knee replacement), 0.5% (elective hip replacement), and 13.4% (non-elective hip replacement). Complication rates were 2.1% (knee replacement), 3.0% (elective hip replacement), and 8.5% (non-elective hip replacement). Inpatient rehabilitation facility utilization rates were 6.0% (knee replacement), 6.7% (elective hip replacement), and 23.5% (non-elective hip replacement). Skilled nursing facility utilization rates were 33.9% (knee replacement), 33.4% (elective hip replacement), and 72.1% (non-elective hip replacement). Readmission rates were 6.3% (knee replacement), 7.0% (elective hip replacement), and 19.2% (non-elective hip replacement). Patients’ age and clinical characteristics yielded consistent patterns across all outcomes.

Conclusions

Outcomes in our national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries receiving lower extremity joint replacements varied across procedure types and patient characteristics. Future research examining trends in access to care, resource use, and care quality over bundled episodes will be important for addressing the challenges of value-based payment reform.

Keywords: bundled payments, mortality, readmissions, complications, post-acute care

INTRODUCTION

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) intends to include more than half of Medicare total reimbursements in alternative payment models by the end of 2018.1 The goal is to make providers more “accountable for the quality and cost of the care they deliver to patients.”1, p.897 Alternative payment models include both accountable care organizations and episode-based payments. An example of a recently implemented episode-based payment model is the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) program.2

In the current fee-for-service payment model, each provider along the continuum of care receives specified payments for the services provided, regardless of prior or subsequent costs and outcomes.3 Under the CJR program, hospitals in the selected geographic areas will be responsible for costs and outcomes over the continuum of care. These providers will receive retrospective bundled payments for lower extremity joint replacement procedures and related care over the 90 days following discharge. “Related care” includes inpatient and outpatient services, rehabilitation, laboratory services, Part B drugs, durable medical equipment, and hospice.2

The transition to alternative payment models is a time of uncertainty “likely to have an extremely steep learning curve” for providers.4, p.7 Identifying targets for care improvement that reduce resource utilization over episodes of care will be critical. The primary objective of this study was to perform comprehensive descriptive analyses of outcomes over 90-day episodes of care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries undergoing lower extremity joint replacement procedures. The outcomes of interest were mortality, medical and surgical complications, hospital readmissions, and inpatient postacute care utilization. Conditions resulting in complications and readmissions were also examined. Our findings will 1) help inform providers on potential targets for care improvement, 2) help us understand how national quality metrics, such as readmissions or complications, perform over 90-day episodes of care, and 3) provide a baseline for tracking changes as providers respond to the pressures of episode-based payments, such as the CJR. We stratified our sample into three groups, patients receiving elective total knee arthroplasties, elective total hip arthroplasties, and non-elective total hip arthroplasties. We hypothesized outcomes would differ across these patient populations.

METHODS

Data Sources

The following 100% national Medicare files from 2012–2014 were used to address the study objectives: Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR), Beneficiary Summary, and Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Date Set 3.0 (MDS). The MedPAR file contains finalized Part A claims for all inpatient stays, including those in acute care hospitals, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), and inpatient rehabilitation facilities. This file was used to identify our cohort of interest- Medicare beneficiaries undergoing lower extremity joint replacements. Claims data from this file were also used to detect complications, readmissions, and post-acute care utilization. The Beneficiary Summary file contains beneficiary sociodemographic information and monthly enrollment (Part A fee-for-service and HMO). Patient sociodemographic information and mortality were extracted from this file. This file was also used to identify those with continuous Part A enrollment over the relevant observation windows. The MDS file contains assessment information from SNF and long-term care nursing home stays. We used this file to identify patients residing in long-term care at the time of their joint replacement procedure. Patient information was linked across files and claims using unique, encrypted beneficiary identification numbers. The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board. A Data Use Agreement was completed following CMS requirements.

Patient Population

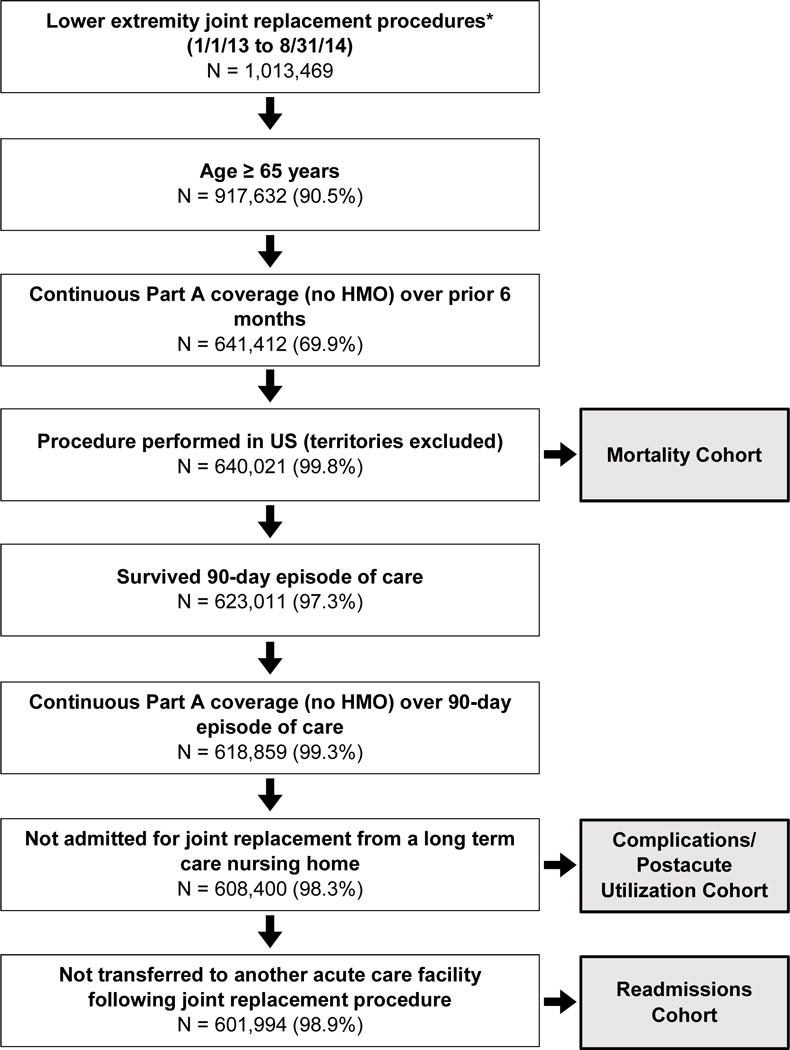

The population of interest was Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries undergoing an elective knee replacement, elective hip replacement, or non-elective hip replacement procedure between January 1, 2013 and August 31, 2014 (N=1,013,469). Joint replacement claims after August were excluded to ensure all complications and readmissions were captured in the 2014 data, even those resulting in a lengthy rehospitalization (30 days) and occurring at the end of the 90-day observation window. If a patient had multiple joint replacements over the study period, one procedure was randomly selected for inclusion.5 We limited our cohort to those 65 years and older (N=917,632) with continuous Part A coverage (no HMO enrollment) over the six months prior to their joint replacement procedure (N=641,412). Continuous Part A coverage allowed a six-month look back at prior hospitalizations and comorbidities. We also included only those who underwent surgery in the United States, not a territory (N=640,021). This initial cohort was used for examining mortality. Two additional cohorts were created for analyses of the remaining outcomes.

To examine complication rates and post-acute care utilization over the 90-day episode of care, additional exclusion criteria were applied. Patients had to survive (N=623,011) and have continuous Part A coverage (N=618,859) for 90 days following the joint replacement procedure. Continuous Part A coverage was required for identifying claims-based outcomes (i.e. complications, post-acute care utilization, and readmissions). We also excluded those admitted from long-term care nursing homes, as they are a distinct cohort and nursing home residence may influence these outcomes.6–8 The complications/post-acute care utilization cohort included 608,400 patients.

Finally, for examining readmissions, patients transferred from one acute care setting to another were excluded, per specifications of the Hospital-Level 30-day All Cause Risk-Standardized Readmission Rate Following Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) measure (N=601,994). Refer to Figure 1 for detailed selection of cohorts.

Figure 1. Cohort selection.

Number of eligible cases remaining as criteria applied. Percentages are percent remaining from the previous step. *Elective knee replacement, elective hip replacement, and non-elective hip replacement procedures. Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; US, United States

Outcomes

Mortality

All-cause mortality over the 90-day episode of care was identified using beneficiary death date from the Beneficiary Summary file. Patients were classified as “alive” or “dead” at the end of the 90-day post-discharge observation window.

Medical and Surgical Complications

Medical and surgical complications were identified using specifications from the Hospital-Level Risk-Standardized Complication Rate Following Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty Algorithm, Version 5.0.5 This measure is endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF) and used for quality reporting on the Hospital Compare website.9 It is one of the quality measures being collected on facilities participating in the CJR program.2

Complications include acute myocardial infarction (AMI), pneumonia, sepsis/septicemia/shock, surgical site bleeding, pulmonary embolism, mechanical complications, and periprosthetic joint infection/wound infection.5 Under the CJR model, hospitals are accountable for complications occurring while the patient is under their care for the joint replacement procedure and for complications occurring post-discharge, if the complication results in a hospital readmission. The post-discharge observation windows vary across complications; however, all start on the day of hospital admission for the procedure.5 Providers are accountable for AMI, pneumonia, and sepsis/septicemia/shock occurring within seven days, surgical site bleeding and pulmonary embolism occurring within 30 days, and mechanical complications and periprosthetic joint infection/wound infection occurring within 90 days.5 Per measure specifications, complications were defined as a dichotomous outcome. Patients experiencing one or more complications were considered to have the outcome of interest. The dichotomous complication variable was used for calculating overall rates. For analyses examining complication conditions, all complications were included.

Readmissions

Unplanned hospital readmissions were identified using the Hospital-Level 30-day All Cause Risk-Standardized Readmission Rate Following Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) Algorithm, Version 5.0.10 This measure is endorsed by NQF and used for quality reporting on the Hospital Compare website.9 We extended the observation window to include all readmissions within 90-days of hospital discharge. Readmissions were considered a dichotomous outcome. Reasons for the first readmission (ICD-9 code) were extracted for reporting. Readmissions and complications, as described above, were not mutually exclusive outcomes. Post-discharge complications are by definition a readmission.5

Post-acute Care Utilization

We defined post-acute care utilization as the number of inpatient days spent in an SNF or inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF). MedPAR claims data were used to identify stays in either setting within 90-days of hospital discharge. Setting-specific total days were calculated by summing lengths of stay for all identified claims. Post-acute stays extending beyond the end of the 90-day episode were truncated on day 90 for reporting.

Patient Characteristics

The following sociodemographic characteristics were extracted from the Beneficiary Summary file: age, sex (male/female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, other), disability entitlement (disability original reason for Medicare, yes/no), and dual eligibility (Medicare and Medicaid eligible, yes/no). MedPAR claims data were reviewed to obtain information on clinical characteristics, including prior hospitalizations, intensive or coronary care unit utilization (ICU/CCU), procedure hospitalization length of stay, and comorbidities. Prior hospitalizations (count) were the number of acute care stays over the six months preceding the lower extremity joint replacement procedure. A dichotomous ICU/CCU utilization variable (yes/no) was created, indicating whether patients were admitted to the ICU or CCU during their procedure hospitalization. Finally, Elixhauser comorbidities were identified by reviewing the diagnoses associated with all hospitalizations over the prior 6 months, including the joint replacement procedure hospitalization.11 The Elixhauser approach was developed for use with administrative datasets and identifies 31 comorbid conditions, defined as diagnoses that may impact healthcare utilization and/or mortality.11,12

Data Analysis

The cohorts were stratified into three groups for analyses: elective knee replacement, elective hip replacement, and non-elective hip replacement procedures. The Hospital-Level Risk-Standardized Complication Rate Following Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty measure specifies ICD-9 codes that disqualify hip replacements from inclusion as “elective” procedures.5 We used these codes to identify our non-elective hip replacement group (Supplement 1). Observed rates of each outcome were calculated for the three procedure groups, as well as rates by patient characteristics.

Complications were categorized as AMI, pneumonia, sepsis/septicemia/shock, surgical site bleeding, pulmonary embolism, mechanical complications, or periprosthetic joint infection/wound infection per measure specifications.5 Rates of complications across the categories were calculated for each procedure. Complication rates were also calculated and stratified by whether they occurred during the joint replacement hospitalization or post-discharge.

Primary diagnoses (ICD-9 codes) of the first unplanned readmissions were grouped into Clinical Classification Software (CCS) diagnostic categories.13 These diagnostic categories were developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project to group ICD-9 codes into clinically meaningful categories.13 Frequencies of each CCS category were calculated to identify common reasons for readmissions for each procedure.

RESULTS

Mortality

The mortality cohort (N=640,021) included 360,520 knee replacement, 168,848 elective hip replacement, and 110,653 non-elective hip replacement procedures. Mortality rates were 0.37% (knee replacement), 0.48% (elective hip replacement), and 13.43% (non-elective hip replacement) over the 90-day episode. Rates by patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Similar patterns were observed across all groups. Mortality rates increased with increasing age, number of prior hospitalizations, procedure hospital length of stay, and number of comorbidities. Rates were also higher for males compared to females; non-Hispanic blacks compared to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and Other race/ethnicity; those with dual eligibility; and those with ICU/CCU utilization during their index admission.

Table 1.

Mortality over 90-day episode of care stratified by procedure type (N=640,021)

| Knee Replacement | Elective Hip Replacement | Non-elective Hip Replacement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N | Mortality, % | N | Mortality, % | N | Mortality, % | |

| Overall | 360520 | 0.37 | 168848 | 0.48 | 110653 | 13.43 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| < 70 | 114820 | 0.18 | 50089 | 0.18 | 7988 | 6.33 |

| 70–74 | 105590 | 0.27 | 46365 | 0.32 | 11508 | 7.50 |

| 75–79 | 78787 | 0.43 | 35876 | 0.48 | 16914 | 8.91 |

| 80–84 | 43878 | 0.66 | 23820 | 0.81 | 24158 | 11.75 |

| ≥85 | 17445 | 1.30 | 12698 | 1.61 | 50085 | 18.25 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 131328 | 0.53 | 65504 | 0.59 | 30918 | 18.97 |

| Female | 229192 | 0.28 | 103344 | 0.41 | 79735 | 11.28 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 317769 | 0.37 | 154537 | 0.48 | 101038 | 13.56 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 18397 | 0.43 | 7551 | 0.54 | 3933 | 13.81 |

| Hispanic | 13844 | 0.34 | 3147 | 0.48 | 3199 | 11.88 |

| Other | 10510 | 0.35 | 3613 | 0.39 | 2483 | 9.38 |

| Disability entitlementa | ||||||

| No | 328280 | 0.36 | 156155 | 0.46 | 101436 | 13.58 |

| Yes | 32240 | 0.56 | 12693 | 0.65 | 9217 | 11.75 |

| Dual eligibilityb | ||||||

| No | 332092 | 0.35 | 158961 | 0.46 | 87261 | 13.25 |

| Yes | 28428 | 0.59 | 9887 | 0.79 | 23392 | 14.09 |

| Prior hospitalizations | ||||||

| 0 | 330936 | 0.35 | 153522 | 0.42 | 83492 | 11.86 |

| 1 | 26749 | 0.61 | 13332 | 0.86 | 19238 | 16.78 |

| 2 | 2379 | 1.01 | 1608 | 2.05 | 5434 | 20.30 |

| 3+ | 456 | 1.75 | 386 | 3.11 | 2489 | 25.19 |

| Hospital LOS (days)c | ||||||

| < 4 | 303724 | 0.28 | 143063 | 0.33 | 23918 | 9.51 |

| 4 – 7 | 53550 | 0.63 | 24057 | 0.91 | 69846 | 11.45 |

| >7 | 3246 | 5.36 | 1728 | 6.48 | 16889 | 27.13 |

| ICU/CCUd | ||||||

| No | 345241 | 0.29 | 160786 | 0.39 | 86511 | 10.84 |

| Yes | 15279 | 2.14 | 8062 | 2.22 | 24142 | 22.69 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Sum | ||||||

| 0–1 | 122967 | 0.17 | 65400 | 0.19 | 16809 | 6.15 |

| 2–4 | 204338 | 0.34 | 88997 | 0.46 | 58061 | 10.63 |

| 5+ | 33215 | 1.33 | 14451 | 1.88 | 35783 | 21.38 |

Abbreviations: LOS, length of stay; ICU/CCU, intensive care unit/coronary care unit

“Disability” original reason for receiving Medicare

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid

Length of stay for joint replacement procedure hospitalization

Admitted to ICU or CCU during joint replacement hospitalization

Complications

The cohort for examining complication rates and post-acute care utilization (N=608,400) included 355,155 knee replacement, 166,075 elective hip replacement, and 87,170 non-elective hip replacement procedures. Complication rates were 2.09% (knee replacement), 2.96% (elective hip replacement), and 8.51% (non-elective hip replacement). Rates by patient characteristics are presented in Table 2. Patterns of complication rates were similar to those observed with mortality, except for a few notable differences. In the elective hip replacement group, complication rates were higher for females than males. In the non-elective hip replacement group, rates were highest in the 70–74 years age category, and rates were lowest among non-Hispanic blacks compared to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and Other race/ethnicity.

Table 2.

Complications over 90-day episode of care stratified by procedure type (N=608,400)

| Knee Replacement | Elective Hip Replacement | Non-elective Hip Replacement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N | Complication, % | N | Complication, % | N | Complication, % | |

| Overall | 355155 | 2.09 | 166075 | 2.96 | 87170 | 8.51 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| < 70 | 113253 | 1.76 | 49398 | 2.45 | 7008 | 8.12 |

| 70–74 | 104256 | 1.96 | 45771 | 2.76 | 9912 | 8.81 |

| 75–79 | 77650 | 2.27 | 35342 | 3.07 | 14293 | 8.51 |

| 80–84 | 43066 | 2.57 | 23330 | 3.69 | 19418 | 8.37 |

| ≥85 | 16930 | 3.00 | 12234 | 4.01 | 36539 | 8.57 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 129242 | 2.26 | 64459 | 2.78 | 22874 | 9.90 |

| Female | 225913 | 1.98 | 101616 | 3.07 | 64296 | 8.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 313403 | 2.08 | 152090 | 2.97 | 79609 | 8.53 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 17956 | 2.40 | 7363 | 3.02 | 2974 | 7.97 |

| Hispanic | 13466 | 2.07 | 3067 | 2.58 | 2514 | 8.07 |

| Other | 10330 | 1.81 | 3555 | 2.45 | 2073 | 8.78 |

| Disability entitlementa | ||||||

| No | 323698 | 2.01 | 153743 | 2.80 | 80078 | 8.33 |

| Yes | 31457 | 2.84 | 12332 | 4.89 | 7092 | 10.46 |

| Dual eligibilityb | ||||||

| No | 328085 | 2.01 | 156776 | 2.85 | 72423 | 8.15 |

| Yes | 27070 | 3.01 | 9299 | 4.73 | 14747 | 10.26 |

| Prior hospitalizations | ||||||

| 0 | 326687 | 2.03 | 151503 | 2.85 | 68233 | 7.93 |

| 1 | 25836 | 2.55 | 12787 | 3.74 | 13835 | 10.00 |

| 2 | 2231 | 4.12 | 1473 | 5.63 | 3583 | 11.83 |

| 3+ | 401 | 4.49 | 312 | 7.69 | 1519 | 12.84 |

| Hospital LOS (days)c | ||||||

| < 4 | 299750 | 1.17 | 141110 | 2.15 | 19858 | 4.01 |

| 4 – 7 | 52398 | 5.49 | 23411 | 6.04 | 56263 | 6.88 |

| >7 | 3007 | 34.02 | 1554 | 29.86 | 11049 | 24.89 |

| ICU/CCUd | ||||||

| No | 340417 | 1.74 | 158344 | 2.58 | 70227 | 6.49 |

| Yes | 14738 | 10.08 | 7731 | 10.57 | 16943 | 16.88 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Sum | ||||||

| 0–1 | 121711 | 1.02 | 64742 | 1.77 | 14990 | 4.42 |

| 2–4 | 201426 | 2.12 | 87575 | 3.17 | 47570 | 7.46 |

| 5+ | 32018 | 5.94 | 13758 | 7.16 | 24610 | 13.02 |

Abbreviations: LOS, length of stay; ICU/CCU, intensive care unit/coronary care unit

“Disability” original reason for receiving Medicare

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid

Length of stay for joint replacement procedure hospitalization

Admitted to ICU or CCU during joint replacement hospitalization

Rates stratified by procedure, complication type, and timing (during admission for joint replacement procedure or post-discharge) are presented in Table 3. For patients undergoing knee replacement procedures, the highest complication rate occurring during hospitalization for the procedure was for pneumonia (0.50%). The highest post-discharge complication rate was for periprosthetic joint infections/wound infections (0.46%). For patients undergoing elective and non-elective hip replacements, the highest complication rates occurring during hospitalization for the procedures were for pneumonia (0.44% and 3.43%, respectively), and the highest post-discharge complication rates were for mechanical complications (1.15% and 2.09%, respectively).

Table 3.

Timing and types of complications over 90-day episode of care (N=608,400)

| Complication rate, %

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Elective Knee Replacement | Elective Hip Replacement | Non-elective Hip Replacement | |

| Overall | |||

| AMI | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.97 |

| Pneumonia | 0.55 | 0.47 | 3.50 |

| Sepsis/septicemia/shock | 0.15 | 0.23 | 1.02 |

| Surgical site bleeding | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.68 |

| Mechanical complications | 0.20 | 1.26 | 2.27 |

| Periprosthetic joint infection/Wound infection | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.90 |

| Joint replacement admission | |||

| AMI | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.90 |

| Pneumonia | 0.50 | 0.44 | 3.43 |

| Sepsis/septicemia/shock | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.95 |

| Surgical site bleeding | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.39 |

| Mechanical complications | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Periprosthetic joint infection/Wound infection | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Readmission(s) | |||

| AMI | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Pneumonia | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| Sepsis/septicemia/shock | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Surgical site bleeding | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.31 |

| Mechanical complications | 0.18 | 1.15 | 2.09 |

| Periprosthetic joint infection/Wound infection | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.88 |

Abbreviations: AMI, acute myocardial infarction

Note: Patients could have multiple complications over episode of care, all are included.

Post-acute Care Utilization

Inpatient rehabilitation and SNF utilization varied across the three procedures. Inpatient rehabilitation facility services were utilized by 5.96% of patients undergoing knee replacement procedures, 6.70% of patients undergoing elective hip replacements, and 23.47% of patients undergoing non-elective hip replacements. Skilled nursing facility services were utilized by 33.85% of patients undergoing knee replacements, 33.43% of patients undergoing elective hip replacements, and 72.05% of patients undergoing non-elective hip replacements. These rates are not mutually exclusive. Patients could use both IRF and SNF services over the 90-day window. On average, patients undergoing knee replacements used less IRF (0.59 ± 2.55 days) and SNF (5.87 ± 11.03 days) services than patients undergoing elective hip replacements (0.71 ± 2.92 days, IRF; 6.41 ± 12.36 days, SNF) or non-elective hip replacements (3.19 ± 6.31 days, IRF; 29.03 ± 27.38 days, SNF).

Readmissions

The cohort for examining 90-day readmission rates (N=601,994) included 351,183 knee replacement, 164,508 elective hip replacement, and 86,303 non-elective hip replacement procedures. Readmission rates were 6.32% (knee replacement), 7.02% (elective hip replacement), and 19.22% (non-elective hip replacement). Rates by patient characteristics are presented in Table 4. Patterns were consistent across groups and similar to those observed with mortality and complications.

Table 4.

Hospital readmissions over 90-day episode of care stratified by procedure type (N=601,994)

| Knee Replacement | Elective Hip Replacement | Non-elective Hip Replacement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N | Readmission, % | N | Readmission, % | N | Readmission, % | |

| Overall | 351183 | 6.32 | 164508 | 7.02 | 86303 | 19.22 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| < 70 | 112283 | 4.74 | 49056 | 5.08 | 6916 | 15.86 |

| 70–74 | 103095 | 5.59 | 45391 | 6.00 | 9799 | 16.87 |

| 75–79 | 76664 | 7.16 | 34933 | 7.70 | 14131 | 18.53 |

| 80–84 | 42401 | 8.84 | 23032 | 9.43 | 19234 | 19.46 |

| ≥85 | 16740 | 11.30 | 12096 | 12.09 | 36223 | 20.64 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 127799 | 6.79 | 63860 | 6.88 | 22605 | 22.55 |

| Female | 223384 | 6.06 | 100648 | 7.10 | 63698 | 18.04 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 310029 | 6.24 | 150707 | 7.03 | 78832 | 18.98 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 17576 | 8.10 | 7232 | 8.09 | 2931 | 24.97 |

| Hispanic | 13360 | 6.38 | 3044 | 6.37 | 2499 | 21.37 |

| Other | 10218 | 5.69 | 3525 | 4.94 | 2041 | 17.64 |

| Disability entitlementa | ||||||

| No | 320125 | 6.02 | 152317 | 6.67 | 79294 | 18.85 |

| Yes | 31058 | 9.46 | 12191 | 11.33 | 7009 | 23.40 |

| Dual eligibilityb | ||||||

| No | 324423 | 6.04 | 155315 | 6.77 | 71709 | 18.17 |

| Yes | 26760 | 9.80 | 9193 | 11.24 | 14594 | 24.37 |

| Prior hospitalizations | ||||||

| 0 | 323093 | 5.98 | 150112 | 6.59 | 67585 | 16.79 |

| 1 | 25581 | 9.48 | 12651 | 10.14 | 13696 | 25.14 |

| 2 | 2124 | 16.34 | 1439 | 18.69 | 3528 | 32.45 |

| 3+ | 385 | 29.87 | 306 | 30.07 | 1494 | 43.64 |

| Hospital LOS (days)c | ||||||

| < 4 | 296634 | 5.58 | 139849 | 6.22 | 19609 | 14.13 |

| 4 – 7 | 51597 | 9.74 | 23138 | 10.87 | 55794 | 19.08 |

| >7 | 2952 | 21.00 | 1521 | 21.70 | 10900 | 29.10 |

| ICU/CCUd | ||||||

| No | 336649 | 6.17 | 156869 | 6.78 | 69568 | 17.71 |

| Yes | 14534 | 9.96 | 7639 | 11.91 | 16735 | 25.51 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Sum | ||||||

| 0–1 | 120642 | 4.16 | 64288 | 4.44 | 14874 | 11.14 |

| 2–4 | 199088 | 6.54 | 86692 | 7.58 | 47118 | 17.36 |

| 5+ | 31453 | 13.27 | 13528 | 15.64 | 24311 | 27.78 |

Abbreviations: LOS, length of stay; ICU/CCU, intensive care unit/coronary care unit

“Disability” original reason for receiving Medicare

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid

Length of stay for joint replacement procedure hospitalization

Admitted to ICU or CCU during joint replacement hospitalization

The five most frequent medical conditions resulting in readmissions following each procedure are presented in the Appendix. For knee replacements, readmissions were most frequently for complications of surgical procedures or medical care (12.6%). For elective and non-elective hip replacements, readmissions were most frequently for complications of implant or graft (22.9% and 13.3%, respectively). Septicemia was also one of the top five reasons for unplanned readmissions across all procedures (4.5%, knee replacement; 4.0%, elective hip replacement; 6.8%, non-elective hip replacement).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of our investigation was to perform comprehensive descriptive analyses of outcomes over 90-day episodes of care among Medicare beneficiaries receiving elective knee replacements, elective hip replacements and non-elective hip replacements. Medicare implemented the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement payment program in April 2016. As a result, bundled payments for joint replacements are a reality in selected geographic regions.2 Providers, payers, and consumers are interested in learning more about outcomes during a 90-day episode of care.2 A summary of our results is presented below based on four outcomes: mortality, complications, utilization of post-acute care services, and readmissions.

Mortality

The 90-day mortality rates observed in our cohort for those undergoing elective procedures (knee replacement, 0.4%; hip replacement, 0.5%) were similar to previously reported 30-day rates.6 This suggests that among patients undergoing elective knee and hip replacement procedures mortality rates are low and a majority of deaths occur within the first 30-days following surgery. Patients undergoing non-elective hip replacements are at higher risk of mortality within 90 days. This is an expected finding given that a majority (96%) of non-elective procedures in our cohort were fracture-related. The association between hip fracture and mortality within 90 days is well-established.21

Complications

Previously reported complication rates for patients undergoing knee replacement procedures range from 2.5 to 3.7%4,14,15 and for patients undergoing hip replacements from 2.6 to 3.6%.14,15 The observation windows (e.g., during hospitalization versus 90 days post-discharge) and diagnoses considered “complications” varied across studies. We used the specifications of the NQF endorsed complications metric and observed complication rates of 2.1% following knee replacement procedures, 3.0% following elective hip replacement procedures, and 8.5% following non-elective hip replacement procedures.

Across all three procedure categories, pneumonia was the most common complication occurring during hospitalization for joint replacement. Risk of pneumonia is multifaceted; however, some forms of pneumonia (e.g. bacterial) are considered to have a degree of preventability.16,17 This is encouraging for providers trying to identify targets for improving outcomes and reducing costs over episodes of care. The most common post-discharge complications differed between those undergoing knee and hip replacements. Following knee replacement, periprosthetic joint infection/wound infection was the most common post-discharge complication, and following hip replacement (elective or non-elective), mechanical complications were the most common complications. Of note, periprosthetic joint infection/wound infection and mechanical complications are the complication categories with the longest accountability window (90 days post-admission). Extended surveillance and or/prevention efforts may be required.

Post-acute Care Utilization

Following lower extremity joint replacement procedures patients were more likely to receive post-acute care in an SNF than an IRF. This supports previous research,4 and is likely influenced by current Medicare policies.3 To qualify for Medicare reimbursement as an IRF, at least 60% of a facility’s patients have to meet certain condition criteria. Only patients undergoing bilateral lower extremity joint replacements, those who have a body mass index ≥50, or those aged 85 years or older count towards this compliance threshold.3 Additionally, to be eligible for referral to an IRF following discharge from an acute care hospital, patients must be able to tolerate three hours of intensive therapy per day (5 days per week). These rules and requirements influence the number and distribution of patients who will receive services in an IRF versus a SNF. The requirements will change under bundled payment programs, which could substantially alter post-acute care resource use for some diagnostic groups, including lower extremity joint replacement.2

Under bundled payment models, the focus is on providing services that meet the patients’ needs while containing costs. Post-acute care utilization is a driver of post-discharge costs over lower extremity joint replacement episodes of care.4,15 Under bundled payment models, hospitals will need to consider the cost versus benefit of various post-acute settings when discharging joint replacement patients. This a new consideration for hospitals; currently, hospitals and post-acute providers are distinct “silos” of care reimbursed under separate payment structures.3 The per capita and geographic variation in spending on post-acute care suggests there is room for improvement,18 and post-acute utilization may be a target for reducing episode costs. A community hospital implementing a lower extremity joint replacement bundled payment initiative observed that reducing rates of discharge to inpatient rehabilitation and skilled nursing facilities decreased episode costs.19 Future research should examine trends in post-acute care utilization and long term outcomes following joint replacement procedures to ensure shifts in patterns of post-acute care do not lead to poorer patient outcomes. We provide a baseline for inpatient rehabilitation and skilled nursing facility utilization over 90-day episodes of care.

Readmissions

In our sample the rate of unplanned 90-day readmissions was 6.3% following elective knee replacement procedures and 7.0% for elective hip replacements. The readmission rate for persons receiving a non-elective hip replacement was 19.2%. Our findings support existing research indicating that most 90-day readmissions following lower extremity joint replacements are procedure-related.9,28 Previously reported 90-day readmission rates following knee replacements range from 6.2 to 14.8%.9,20,29 Rates vary depending on the population studied and the approach used to identify readmissions. Prior research has frequently excluded non-elective hip replacements14,15 or grouped them with elective procedures.20 However, non-elective procedures are included in the CJR program, and our findings indicate outcomes differ in this vulnerable population.2

Implications for CJR and Episode Payment Models

In announcing the CJR program, Secretary Burwell stated that the CMS was “embarking on one of the most important steps we will take to improve the quality and value of care for hundreds of thousands of Americans who have hip and knee replacements through Medicare every year.”21 The success of the CJR model will depend on several factors. A key factor is ensuring the payment bundle provides adequate funding to cover the essential services the beneficiary will receive during the episode of care. This will be a challenge for the 90-day episode. Adequate funding and/or risk-adjustment will be critical for ensuring that access to care is not compromised for “high cost” patients and that stinting of care over bundled episodes does not occur.

Another key element to the success of the CJR program is the selection and development of appropriate quality measures. In a recent JAMA Forum article discussing episode payment models, Jha observed that, “Whether the EPM [episode payment model] will improve care or not will be driven in large part by having the right set of quality measures.”22 The CJR 90-day episode payment model includes three quality measures: complications, a survey of hospital consumer satisfaction, and a patient reported outcome (PRO) measure focused on pain management.2 Our findings provide baseline information on complications. Research on patient-based quality measures should be a high priority. This information will be critical for ensuring we continue to deliver patient-centered care as payment models evolve.2,23

Our analyses emphasized quality measures related to resource use. We were particularly interested in unplanned hospital readmissions during the 90-day episode, as this was considered as a potential quality indicator for the CJR program, but was not included in the final rule.3 We believe readmissions may be an important measure to reconsider. Even though the 90-day readmission rates for elective joint replacements are low (5.9% knee, 7.0% hip), our findings suggest many of the common reasons for readmission are potentially preventable. This is more important for non-elective hip replacements where the 90-day readmission rate was 19.2%. Among the top five reasons for readmission in this cohort are septicemia, non-hypertensive congestive heart failure, and urinary tract infections. These should be priority targets for provider and patient education and represent opportunities to improve quality of care and reduce cost. Future research should focus on the provider characteristics and care processes associated with efficiently delivering quality care to joint replacement patients.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. These include the reliability, accuracy and completeness of data collected for billing and administrative functions24 The majority of our analyses are descriptive and included the sample of individuals meeting our inclusion criteria. We did not include adjustments for potential mediating factors. Nor did we examine interactions across rehabilitation impairment conditions or other subgroups. The lack of variables directly measuring socioeconomic status and education in the Medicare claims files limits our ability to document the role of these factors. Our analyses involve a sub-set of the Medicare population receiving lower extremity joint replacements. We only included Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in the fee-for-service program. The decision to not include patients admitted for lower extremity joint replacements from institutional settings (e.g., long-term care nursing homes) changed the case-mix of the persons included in the analyses, and the findings from our study are not representative of the entire Medicare beneficiary population. Research focused on the long-term care nursing home cohort will be an important area for future research.

Our results are based on observed rates of mortality, complications, and readmissions. Conclusions cannot be drawn on patient-level predictors from these data. Finally, it is important to understand that the Medicare files used in our analyses included data 1) prior to the implementation of the CJR program and 2) not specifically from the hospitals participating in the mandatory CJR program.

Conclusion

The shift to 90-day episode-based payment models, such as the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement program, represents an important new approach to the delivery and evaluation of integrated acute and post-acute health services. We studied medical and surgical complications, post-acute care utilization, hospital readmission, and mortality over 90-day episodes of care in a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries undergoing elective knee replacement, elective hip replacement, and non-elective hip replacement procedures. Consistent patterns related to patient characteristics were observed across the three surgical groups. Findings may help providers prepare for episode-based payment models and provide a baseline for evaluating outcomes as the CJR model evolves. Future research examining trends in access to care, resource use, and care quality over bundled episodes will be important for addressing the challenges involved in implementing value-based payment reform.

Supplementary Material

Supplement 1. ICD-9 codes excluded from “elective” procedures in the Hospital-Level Risk-Standardized Complication Rate Following Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty measure.1

Supplement 2. Five most frequent reasons for hospital readmissions over 90-day episodes of care following joint replacement

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01 HD069443 and 5K12HD055929-09); the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (grant number 90AR5009); and the National Institute on Aging (grant number P30-AG024832).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals–HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:897–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Federal Register. Medicare Program; Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Payment Model for Acute Care Hospitals Furnishing Lower Extremity Joint Replacement Services; Final Rule. 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2016 Mar; Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/reports/march-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Accessed 7/20/2016.

- 4.Cram P, Lu X, Li Y. Bundled Payments for Elective Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: An Analysis of Medicare Administrative Data. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2015;6:3–10. doi: 10.1177/2151458514559832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. 2016 Procedure-Specific Measure Updates and Specifications Report, Hospital-Level Risk-Standardized Complication Measure Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA)-Version 5.0. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed 7/15/2016.

- 6.Caldararo MD, Stein DE, Poggio JL. Nursing home status is an independent risk factor for adverse 30-day postoperative outcomes after common, nonemergent inpatient procedures. Am J Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogaisky M, Dezieck L. Early hospital readmission of nursing home residents and community-dwelling elderly adults discharged from the geriatrics service of an urban teaching hospital: patterns and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:548–52. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoverman C, Shugarman LR, Saliba D, et al. Use of postacute care by nursing home residents hospitalized for stroke or hip fracture: how prevalent and to what end? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1490–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare. Available at: https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed July 15, 2016.

- 10.Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. 2016 Procedure-Specific Readmission Measure Updates and Specifications Report, Hospital-Level 30-day Risk Standardized Readmission Measures, Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA)-Version 5.0. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed 7/19/2016.

- 11.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Clinical Classifications Software (CCS); 2015. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/CCSUsersGuide.pdf. Accessed 5/16/2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bozic KJ, Grosso LM, Lin Z, et al. Variation in hospital-level risk-standardized complication rates following elective primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:640–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichols CI, Vose JG. Clinical Outcomes and Costs Within 90 Days of Primary or Revision Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1400–6 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Prevention Quality Indicators Overview. Available at: http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/modules/pqi_resources.aspx. Accessed 6/16/2016.

- 17.RTI International and Abt Associates. Draft Measure Specifications: Potentially Preventable Hospital Readmission Measures for Post-Acute Care. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/Draft-Measure-Specifications-for-Potentially-Preventable-Hospital-Readmission-Measures-for-PAC-.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 18.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/reports/june-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed 7/20/2016.

- 19.Doran JP, Zabinski SJ. Bundled payment initiatives for Medicare and non-Medicare total joint arthroplasty patients at a community hospital: bundles in the real world. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:353–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurtz SM, Lau EC, Ong KL, et al. Hospital, Patient, and Clinical Factors Influence 30- and 90-Day Readmission After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CMS finalizes bundled payment initiative for hip and knee replacements. 2015 Nov 16; Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/11/16/cms-finalizes-bundled-payment-initiative-hip-and-knee-replacements.html. Accessed 8/29/2016.

- 22.Jha AK. JAMA Forum: Will Episode Payment Models Show How to Better Pay for Hospital Care? 2016 Aug 4; Available at: https://newsatjama.jama.com/2016/08/04/jama-forum-will-episode-payment-models-show-how-to-better-pay-for-hospital-care/. Accessed 8/29/2016.

- 23.Tefera L, Lehrman WG, Conway P. Measurement of the Patient Experience: Clarifying Facts, Myths, and Approaches. JAMA. 2016;315:2167–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Walraven C, Austin P. Administrative database research has unique characteristics that can risk biased results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1. ICD-9 codes excluded from “elective” procedures in the Hospital-Level Risk-Standardized Complication Rate Following Elective Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty and/or Total Knee Arthroplasty measure.1

Supplement 2. Five most frequent reasons for hospital readmissions over 90-day episodes of care following joint replacement