Abstract

Background: Scientific evidence for the optimal number, timing, and size of meals is lacking.

Objective: We investigated the relation between meal frequency and timing and changes in body mass index (BMI) in the Adventist Health Study 2 (AHS-2), a relatively healthy North American cohort.

Methods: The analysis used data from 50,660 adult members aged ≥30 y of Seventh-day Adventist churches in the United States and Canada (mean ± SD follow-up: 7.42 ± 1.23 y). The number of meals per day, length of overnight fast, consumption of breakfast, and timing of the largest meal were exposure variables. The primary outcome was change in BMI per year. Linear regression analyses (stratified on baseline BMI) were adjusted for important demographic and lifestyle factors.

Results: Subjects who ate 1 or 2 meals/d had a reduction in BMI per year (in kg · m−2 · y−1) (−0.035; 95% CI: −0.065, −0.004 and −0.029; 95% CI: −0.041, −0.017, respectively) compared with those who ate 3 meals/d. On the other hand, eating >3 meals/d (snacking) was associated with a relative increase in BMI (P < 0.001). Correspondingly, the BMI of subjects who had a long overnight fast (≥18 h) decreased compared with those who had a medium overnight fast (12–17 h) (P < 0.001). Breakfast eaters (−0.029; 95% CI: −0.047, −0.012; P < 0.001) experienced a decreased BMI compared with breakfast skippers. Relative to subjects who ate their largest meal at dinner, those who consumed breakfast as the largest meal experienced a significant decrease in BMI (−0.038; 95% CI: −0.048, −0.028), and those who consumed a big lunch experienced a smaller but still significant decrease in BMI than did those who ate their largest meal at dinner.

Conclusions: Our results suggest that in relatively healthy adults, eating less frequently, no snacking, consuming breakfast, and eating the largest meal in the morning may be effective methods for preventing long-term weight gain. Eating breakfast and lunch 5–6 h apart and making the overnight fast last 18–19 h may be a useful practical strategy.

Keywords: meal frequency, meal timing, BMI, Adventist Health Study 2, weight control

Introduction

Like macronutrient composition and quality, meal frequency and timing are important aspects of nutrition. Excessive energy intake increases the risk of obesity and chronic disease, and obesity is a leading cause of disability and death in Western countries (1). A large proportion of the increased risk of obesity and chronic disease is related to aging (2, 3). Eating more frequently (snacking) is often recommended as a strategy for weight loss. It is presumed to reduce hunger (4) and thus energy intake and body weight.

However, the widely held opinion that eating more frequently is better for weight control than eating larger meals less frequently is not as scientifically well established as many believe. Some observational studies have suggested that people who consumed more snacks were less likely to be obese (5), but other large prospective studies seemed to have shown that frequent snacking leads to weight gain (6, 7), increased abdominal and liver fat (8), and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (9, 10) not only because of the higher energy intake mainly from added sugars (11) but also because of increased food stimuli (12), hunger, and the desire to eat (13).

In keeping with this, reduced meal frequency can prevent the development of obesity and chronic diseases and extend life spans in laboratory animals (14, 15). Mice under time-restricted feeding consumed equivalent calories from a high-fat diet as those with ad libitum access yet were protected against obesity and diabetes (16, 17). Intermittent fasting leads to a prolonged life span and positively affects glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in mice (14, 15, 18–21).

The effect of meal frequency on body weight in humans has been studied in only a small number of randomized clinical trials. These trials typically included small numbers of participants (maximum: 40), were only short term (maximum: 8.5 wk), and varied greatly in meal frequency manipulations (range: 1–12 meals/d). A thorough summary and overview of these trials has been published recently (22). An important consideration relevant to meal frequency is macronutrient quality. Some research suggests that the higher consumption of protein more frequently may be beneficial in overweight subjects (23). The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee stated in 2010 that there was a lack of research on meal frequency and body-weight management in humans and that research on this topic was greatly needed (24).

Data on meal timing have been better established than those on meal frequency. Some studies have suggested that eating meals later in the evening may adversely influence the success of a weight-loss therapy (25, 26). It has also been observed that eating breakfast regularly may protect against weight gain (27, 28) by reducing absolute energy intake within the day (29). Based on the existing data, the 2010 US dietary guidelines included a specific recommendation for breakfast consumption (30).

In this study, we sought to investigate the relation between meal frequency and timing and changes in BMI (in kg/m2) among subjects in the Adventist Health Study 2 (AHS-2), a relatively healthy population in the United States and Canada, and longitudinally assess weight change over a mean of >7 y. We hypothesized that increased meal frequency, together with a shorter overnight fast, would be associated with increases in BMI and that skipping breakfast and having dinner as the largest meal of the day would also be associated with an increase in BMI. We tested these hypotheses in a large number of free-living subjects who had a wide variety of baseline body sizes and were studied over a period of several years.

Methods

Study design and subject selection.

Recruitment and selection methods of the cohort have been described previously (31). Briefly, adult members of Seventh-day Adventist churches throughout the United States and Canada aged ≥30 y were enrolled and completed the baseline AHS-2 “Connecting Lifestyle to Disease and Longevity” questionnaire, which included medical history, dietary habits, physical activity, and demographic information. Follow-up through the biennial Hospital History Form (HHF) recorded hospitalizations, major health events, and some lifestyle and demographic factors. In the fourth biennial HHF (HHF4), the questions about meal frequency and timing were asked.

Approximately 27% of the cohort was black with US and Caribbean origin, and the remaining participants were primarily white, with a minor proportion from other races. The Loma Linda University Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol, and all study participants provided written consent at the time of enrollment.

The following exclusions were implemented: age <30 y, invalid responses corresponding to unanswered pages or sections of the questionnaire, missing values for main exposure variables, BMI out of range (<14 or >60) at baseline or HHF4, weight changes >100 kg between baseline and HHF4, <4 or >11 h of sleep, and the last meal of the day before 1100. The numbers of participants excluded are shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

Outcome data.

The primary outcome of interest was change in BMI per year comparing BMI at baseline with that ascertained later from HHF4. The change per year accounted for variable follow-up time. BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight ascertained in both questionnaires. A high validity of self-reported BMI has been demonstrated previously in this population, in which the correlation coefficient with measured values was 0.97 (32).

Exposure variables.

In HHF4, study participants were also asked to give the exact times of the largest and smallest meals and of all other meals and snacks consumed per day. The number of meals and snacks consumed per day, length of overnight fast, consumption of breakfast, and timing of the largest meal were the exposure variables. Breakfast was defined as a meal eaten between 0500 and 1100, lunch between 1200 and 1600, and dinner between 1700 and 2300.

Dietary assessment and dietary covariates.

Dietary intake was assessed with the use of a self-administered FFQ at baseline. The FFQ was calibrated against multiple 24-h dietary recalls. In general, validity correlations were moderate to high for macronutrients, FAs, vitamins, minerals, and fiber (33). Dietary patterns were derived from the reported consumption of foods. We used total energy intake, protein consumption, and dietary pattern as the dietary covariates.

Lifestyle and sociodemographic covariate data.

Sociodemographic and lifestyle factors were assessed with the use of a questionnaire at baseline and included age, sex, marital status, minutes of exercise per week, hours of daily sleep, hours of television watching per day, and high blood pressure medication use. Ethnicity was categorized as black and nonblack. Education was categorized as high school or less, some college, and a bachelor’s degree or higher. Personal income was categorized as <$20,000, ≥$20,000–50,000, and >$50,000/y.

Statistical analysis.

All data were analyzed with the use of SAS/STAT version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Linear regression analyses stratified on baseline BMI (4 categories) included adjustments for age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, personal income, dietary pattern, exercise, sleep, television watching, energy intake, and use of high blood pressure medications. The dependent variable was BMI at HHF4 – BMI at baseline ÷ years to provide a rate of change.

Moderate- to large-valued correlations between some exposure variables of interest (collinearity) necessitated 2 separate analyses. The time of the largest meal and all covariates were used in both models, with the length of overnight fast in the first model and number of meals and snacks and eating breakfast in the second model. The one significant interaction with larger estimates was retained and was present in both models (interaction between race and lunch as the largest meal). All covariates were set at the reference or mean values (for categorical and continuous variables, respectively) to capture the effect of the main exposure variables.

A total of 8909 subjects were excluded from the analysis because of missing data (Supplemental Figure 1). All tests were of the null hypothesis that the β coefficient estimating the effect of interest was zero (Wald test). Significance was defined as α = 0.05.

Results

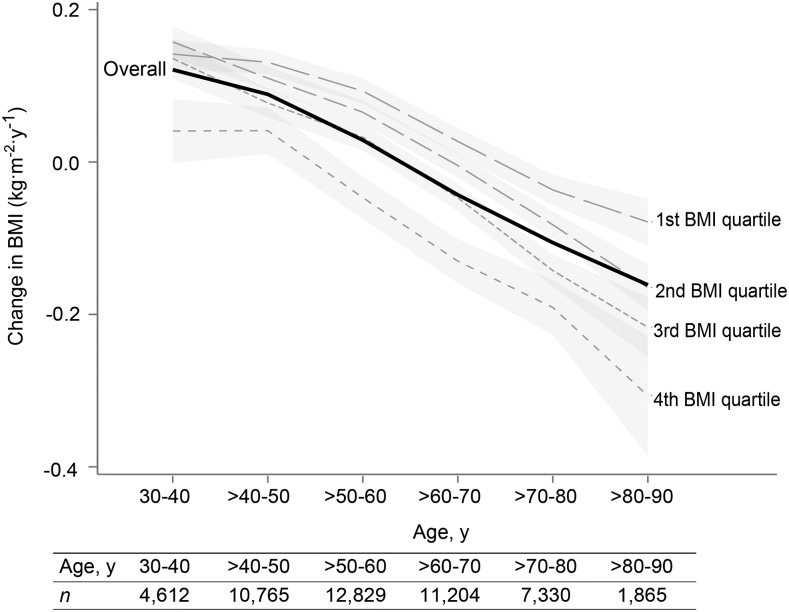

The baseline characteristics of this nonsmoking Adventist study population are shown in Table 1. We analyzed data from 50,660 subjects, and the mean ± SD follow-up time was 7 ± 1 y. The mean ± SD change in BMI per year was 0 ± 0.4, but it was dependent on age: participants aged ≤60 y experienced increases in BMI on average in contrast to those of an older age, whose BMI decreased over time (Figure 1). Thus, the term relative increase or decrease in BMI per year was necessary because of the striking underlying age trends. For instance, a relatively decreased BMI compared with some reference situation may still be an absolute increase (but less so) in younger subjects.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the AHS-2 study population1

| Variables | Values |

| Age, y | 58 ± 132 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |

| At baseline | 27 ± 5 |

| At HHF4 | 27 ± 6 |

| Difference | 0 ± 3 |

| Change per year | 0 ± 0.4 |

| Follow-up time, y | 7 ± 1 |

| Dietary energy, kcal/d | 1930 ± 727 |

| Dietary fiber, g/d | 33 ± 16 |

| Dietary protein, g/d | 70 ± 29 |

| Number of meals and snacks/d | 4 ± 1 |

| Mean overnight fast, h | 14 ± 3 |

| Exercise, min/wk (moderate intensity) | 85 ± 96 |

| Sleep, h/d | 7 ± 1 |

| Television watching, h/d | 2 ± 1 |

| Sex | |

| Missing | 11 (0.02) |

| Women | 31,346 (64) |

| Men | 17,339 (36) |

| Race | |

| Missing | 184 (0.4) |

| Nonblack | 40,636 (83) |

| Black | 7876 (16) |

| Education | |

| Missing | 412 (1) |

| ≤High school | 21,586 (44) |

| Trade school, some college, or associate’s degree | 8275 (17) |

| ≥College | 18,423 (38) |

| Annual income | |

| Missing | 3334 (7) |

| <$20,000 | 18,448 (38) |

| ≥$20,000–50,000 | 16,737 (34) |

| >$50,000 | 10,177 (21) |

| Marital status | |

| Missing | 634 (1) |

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 37,508 (77) |

| Married/common law | 10,554 (22) |

| Type of residence | |

| Missing | 790 (2) |

| Owned/rented | 46,579 (96) |

| Assisted | 215 (0.4) |

| Nursing home | 84 (0.2) |

| Family/friends | 1028 (2) |

| Smoking status | |

| Missing | 346 (1) |

| Never | 40,177 (83) |

| Previous | 7905 (16) |

| Current | 268 (1) |

| Alcohol use within the last 2 y | |

| Missing | 167 (0.3) |

| No | 43,861 (90) |

| Yes | 4668 (10) |

| Diabetes | |

| Missing | 79 (0.2) |

| No | 46,326 (95) |

| Yes | 2291 (5) |

| Use of statin | |

| Missing | 2889 (6) |

| No | 40,983 (84) |

| Yes | 4824 (10) |

| Use of high blood pressure medication | |

| Missing | 2671 (5) |

| No | 39,299 (81) |

| Yes | 6726 (14) |

| Consumption of breakfast | |

| No | 3229 (7) |

| Yes | 45,467 (93) |

| Largest meal consumed per day | |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Breakfast | 10,285 (21) |

| Lunch | 20,234 (42) |

| Dinner | 18,177 (37) |

All values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. AHS-2, Adventist Health Study 2; HHF4, fourth biennial Hospital History Form.

Mean ± SD (all such values).

FIGURE 1.

Changes in BMI per year in the AHS-2 population by quartile of baseline BMI (interrupted lines) and over all subjects (solid line). The regression model was change in BMI per year = α + Σ(βj ⋅ agej) + Σ(βk ⋅ covariatek), where j represents the J-1 age range indicator variables, and k the K covariates. Data are the predicted values of change in BMI per year at a particular age, conditional on covariates at mean values (continuous variables) or reference values (categorical variables), with 95% confidence bands. AHS-2, Adventist Health Study 2.

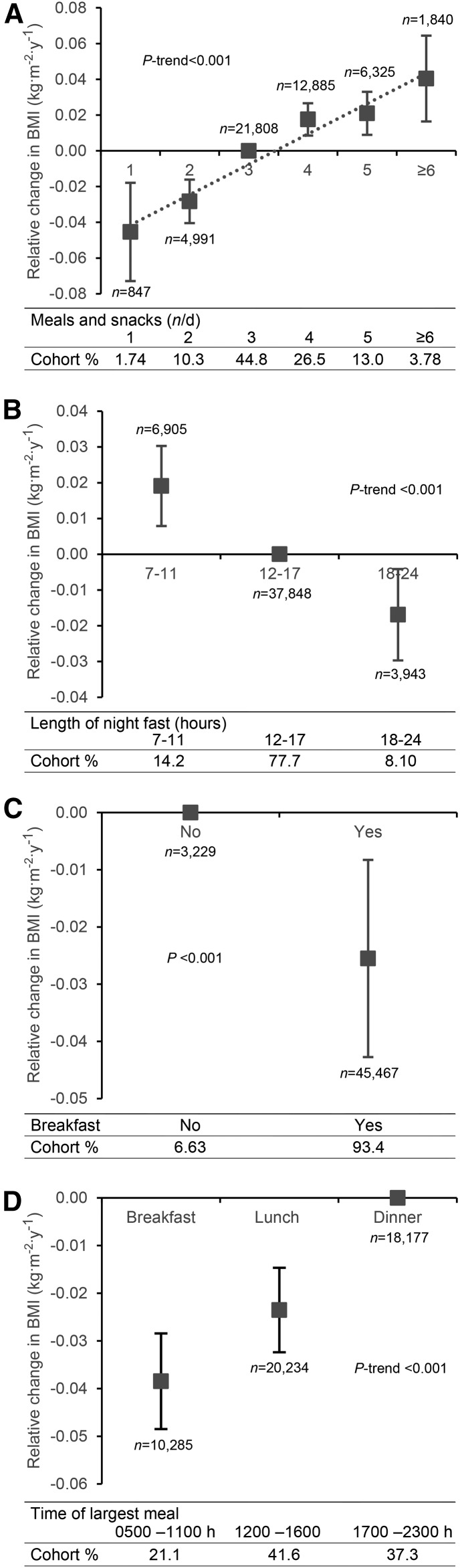

As shown in Figure 2, eating 1 (prevalence: 1.7%) or 2 (prevalence: 10.3%) meals/d was associated with a relative decrease in BMI (−0.05; 95% CI: −0.07, −0.02 and −0.03; 95% CI: −0.04, −0.02, respectively) compared with eating 3 meals/d (prevalence: 44.8%). On the other hand, eating >3 meals (snacking) compared with 3 meals/d was associated with a relative increase in BMI per year [0.02 (95% CI: 0.01, 0.03); 0.02 (95% CI: 0.01, 0.03); and 0.04 (95% CI: 0.02, 0.06)] for 4 (prevalence: 26.5%), 5 (prevalence: 13%), and ≥6 (prevalence: 3.8%) meals/d, respectively. We observed a linear association between the number of meals eaten per day and changes in BMI: more meals per day were associated with a greater increase in BMI, even within the snacking range (>3 meals/d; P-trend <0.001) (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

The relation between meal frequency and timing and the change in BMI per year relative to the reference exposure value in the AHS-2 population. (A) Number of meals and snacks consumed per day (reference: 3 meals/d), (B) length of overnight fast (reference: 12–17 h), (C) consumption of breakfast (reference: no), and (D) timing of the largest meal (reference: dinner). P values are given for trends or differences (as appropriate). Data are predicted values ± 95% CIs conditional on covariates at mean or reference values. AHS-2, Adventist Health Study 2.

Corresponding to the meal frequency results, subjects who had a long overnight fast (prevalence: 8.1%) experienced a relative decrease in BMI per year (−0.02; 95% CI: −0.03, −0.004) in contrast to those with a short overnight fast (prevalence: 14.2%) whose BMI was relatively increased (0.02; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.03), both compared with a medium overnight fast (prevalence: 77.7%) of 12–17 h (P-trend <0.001) (Figure 2B).

Breakfast eaters (prevalence: 93.4%) experienced a relative decrease in their BMI compared with breakfast skippers (prevalence: 6.6%) (−0.03; 95% CI: −0.04, −0.01; P < 0.001) (Figure 2C). Those whose largest meal was breakfast (prevalence: 21.1%) experienced the largest relative decrease in BMI (−0.04; 95% CI: −0.05, −0.03) compared with those who ate their largest meal at dinner (prevalence: 37.3%), and those who ate lunch as the largest meal (prevalence: 41.6%) experienced a smaller relative decrease in BMI (−0.02; 95% CI: −0.03, −0.01; P-trend <0.001) (Figure 2D).

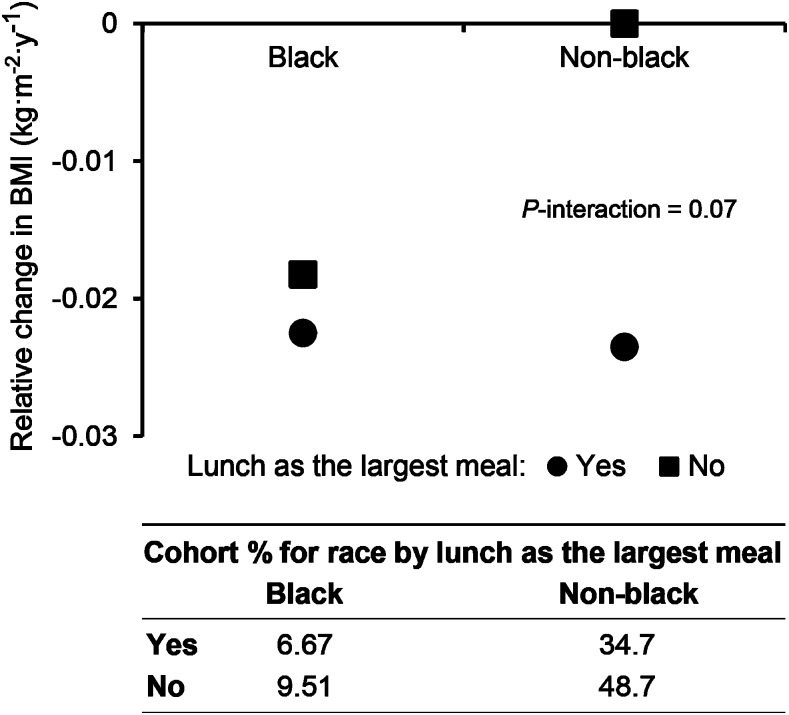

A borderline significant interaction was observed between eating the largest meal at lunch and race on the change in BMI (P = 0.07) (Figure 3). Eating lunch as the largest meal of the day was associated with a relative decrease in BMI only in nonblack subjects (Figure 3). There was little evidence of interactions with age and no significant differences.

FIGURE 3.

Modification by race of the association between the relative change in BMI according to whether lunch was the largest meal. The P value is for interaction by race. Data are predicted values of change in BMI per year conditional on the chosen values of race and lunch as the largest meal, with other covariates at mean or reference values.

Discussion

Principal findings.

This study investigated the relation between meal frequency, timing, and changes in BMI in the AHS-2 cohort. In accordance with our hypotheses, we demonstrated that eating 1 or 2 meals/d was associated with a relative decrease in BMI compared with 3 meals/d. Furthermore, participants who ate >3 meals/d experienced a relative increase in BMI: the more meals and snacks per day, the greater the increase in BMI. Correspondingly, the change in BMI among those with a long overnight fast was relatively decreased compared with those with a medium overnight fast, but both had a relatively decreased change in BMI compared with those with a short overnight fast. Breakfast eaters experienced a relative decrease in their BMI compared with breakfast skippers. Those eating their largest meal at breakfast experienced a relatively large decrease in BMI compared with those eating their largest meal at lunch or dinner.

A striking feature of these analyses is that there were underlying powerful age-dependent trends in BMI that the meal patterns could nevertheless modify. BMI increased in subjects aged <60 y and decreased on average thereafter (Figure 1). Thus, meal patterns that favor relative decreases in BMI may not always be healthful in subjects already experiencing substantial decreases for other reasons such as chronic disease.

Findings in relation to other research.

The finding that eating less frequently (and eating no snacks) may prevent or reduce increases in BMI is consistent with 2 previous large prospective studies that found that frequent eating (and snacking) is associated with a greater risk of a 5-kg weight gain or risk of developing overweight and obesity (6, 7), mainly because of unhealthy food choices (34) and uncontrolled energy balance (35). These studies were limited to a fixed 5-kg weight change or exceeding particular BMI values rather than treating weight change as a continuous variable as we did.

The positive linear response with meal frequency observed in our study even within the snacking range (>3 meals/d) highlights the potential importance of these findings from a public health perspective, although macronutrient quality must also be considered. We performed analyses with the exposure being the number of eating episodes to give more power when reflecting changes in BMI. The snacks-alone analyses added no more information than those scored as >3 eating episodes.

The association that we describe between a long overnight fast and a relative decrease in BMI provides further support for the benefits of less frequent eating. Our results are in strong agreement with animal studies that have demonstrated protective effects of intermittent fasting regimens against the development of obesity (14, 15). Thus, a consideration of this variable views meal frequency and changes in body size from a different perspective.

The observed relation between breakfast consumption and a relative decrease in BMI is also in line with previous studies (27, 28). It has been shown that people who usually skip breakfast have an increased risk of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases (28, 36, 37). Our study adds to this evidence.

This study has a relatively precise timing for the largest meal. Two other studies have also suggested that consuming a large meal in the morning may be an effective weight-loss strategy (38, 39). The ability to examine the timing of the largest meal provides information about the distribution of total energy intake during the day. Eating 2 large meals/d, breakfast and lunch, and having a longer overnight fast every day, is a historically recommended Adventist meal pattern. Its benefits and potential risks and its effects on protein synthesis and energy balance need to be further studied in large-scale long-term studies as well as in randomized clinical trials.

The relatively small estimated effects on BMI per year of each meal frequency and timing exposure variable were similar in size to a study that evaluated effects of dietary differences on BMI over time in another population containing many vegetarians (40). However, from a public health perspective, having a population of young adults avoid a weight gain of 12–15 pounds, which is often very difficult to lose in a healthy fashion, would be a great advantage. It is also likely that by following a change in meal pattern there may be a period of more rapid relative change in BMI for several months.

Our results also differ from most other reports in that they describe the outcome of change in BMI as a continuous variable over time in relation to meal frequency and timing. Thus, all subjects provided an endpoint, not just those who achieved a fixed BMI or BMI change endpoint. The striking underlying dependency of the direction of the BMI change variable on age (≥60 y) complicates the interpretation of the meaning of such trends, particularly seeing that as distinct from the underlying trend the directions of the effects of meal frequency and timing on changes in BMI seem to be the similar at all ages. Similar trends in changes in BMI with age have been reported from Australia (41), Norway (42), and Sweden (43), although the oldest age groups were not represented in these studies. We performed separate analyses for those aged ≤60 and >60 y, and the effects of meal frequency and timing on changes in BMI seemed very similar in magnitude and direction.

Potential mechanisms.

Although the exact mechanisms linking meal frequency and timing and the regulation of body weight are, to our knowledge, unknown, we suggest several potential pathways. First, satiety hormones, such as leptin or ghrelin, may be involved. Ghrelin is a fast-acting orexigenic hormone, and its concentrations increase preprandially and especially at night (44). Correspondingly, hunger has its intrinsic circadian peak in the evening, promoting the tendency to eat the largest meals late in the day (45). However, eating a large breakfast reduces hunger, cravings (especially for sweets and fats), and postprandial ghrelin concentrations, thus counteracting weight gain (46). Postprandial ghrelin suppression depends on insulin release, and frequent eating seems to disrupt this relation similar to other insulin-resistant states (47). It is possible that some with shorter overnight fasts who snack at night have a sleep disorder. Sleep disorders have inconsistently been associated with weight gain in adults (48, 49). Thus, it may be that these changes in meal patterns affect energy intake and hence body weight in several ways.

Second, meal frequency and timing can reset and amplify the peripheral circadian clocks and the clock genes that control downstream metabolic pathways, which are perturbed in obesity and metabolic disease (50). It has been shown in experimental models and in humans that both feeding and fasting change transcription rates and the circadian phase of these genes (51, 52). Time-restricted feeding seems to improve the circadian oscillations of the key metabolic regulators such as cAMP response element-binding protein, mammalian target of rapamycin, and AMP-activated protein kinase (16).

Third, experimental data have also suggested that reduced meal frequency (and intermittent fasting) can prevent the development of obesity and is associated with less oxidative damage as well as higher stress resistance through the production of protein chaperones (e.g., heat-shock proteins) and growth factors (such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor) (14, 15), possibly because of improved adipose tissue signaling and subsequent less increase of fat depots (53).

Finally, regular breakfast consumption seems to increase satiety, reduce total energy intake, improve overall dietary quality (increasing especially consumption of fiber- and nutrient-rich foods commonly consumed at breakfast), reduce blood lipids, and improve insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance at a subsequent meal (28, 37, 54). There is also evidence of an increase in physical-activity thermogenesis, increase in adipose tissue insulin sensitivity, and more stable plasma glucose concentrations (lower glucose variability) during the day as a result of daily breakfast consumption (54). On the other hand, eating meals in the evening generally has the opposite effects (55), all of which adversely affect body weight regulation.

Strengths and weaknesses.

This study has several strengths, including a long-term longitudinal (although nonprospective) study design with a large number of participants and relatively high percentage of participants eating breakfast as their largest meal. The population was diverse in terms of age, sex, race, geographic location, and socioeconomic status, enhancing the relevance of its findings to the North American population. We used clearly specified measurements of dietary practices and extensive data on covariates with which to explore confounders and mediators of the associations under investigation. There were no major differences between the analytical sample and the excluded participants in BMI, age, sex, or meal frequency. One unique feature of our study lies in the more precise meal timing, which enabled us to assess the impact of the duration of the overnight fast and the timing of the largest meal more accurately. Another distinction of this study is the fact that we followed people with a wide range of age and BMI and observed significant changes in BMI in relation to meal frequency and timing across all ages, even in seniors who had lost weight during the follow-up.

Potential weaknesses include the nonprospective nature of our analyses because the meal pattern exposure variables were not gathered at the beginning of the follow-up. Thus, reverse causation must be considered. If those experiencing increasing weight were motivated to start consuming calories earlier in the day (i.e., breakfast), this would be inconsistent with our results. If such persons for some reason were instead motivated to consume calories later in the day, this could be consistent with our results. Stratifying on baseline BMI constrains the analyses to be within subjects having similar BMI starting points, which would be expected to partially compensate for such hypothesized cognitive effects. Furthermore, because of the strong age-related trends in BMI after the age of 60 y, even those with relative weight gains will actually usually be losing weight. This makes a reverse cause motivated by cognitive consequences of weight changes less plausible (although not impossible) because the changes observed by subjects, although relatively higher or lower, will often not reflect those descriptors in absolute terms. However, similar effects remain across the age spectrum.

The response rate at HHF4 was ∼55% of the cohort at baseline, so some response bias was possible. Probable errors in self-reported measures of meal frequency and timing (which were not validated) and other lifestyle-related data are acknowledged. Another potential weakness is the lack of information on the amount of food consumed per eating episode when seeking to explain observed associations. Although appropriate adjustments for confounders were made, there is still a possibility of some residual confounding. We were not able to differentiate between intentional and unintentional weight loss. Our subjects were health-conscious, nonsmokers, mostly nondrinkers, and those who eat less meat than the general population. However, there is no reason to believe that others subscribing to similar habits would not experience the same results. As with all observational studies, caution must be exercised in inferring causation from the results.

In conclusion, our results suggest that eating less frequently (and eating no snacks), consuming breakfast, and eating the largest meal in the morning may be effective long-term preventive tools against weight gain for those in whom this would be unhealthy. Eating only 2 meals/d, breakfast and lunch 5–6 h apart, may also be an interesting strategy for weight control. Although the annual effects of these meal patterns on BMI are small, they may be very important across a lifetime. The practical implication may be different for younger subjects who are prone to gain weight than for seniors who in contrast tend to lose weight and in whom the suggested meal pattern changes may further increase weight loss. Novel preventive and therapeutic strategies should incorporate not only the energy and macronutrient content but also meal frequency and timing. Future research on mechanisms might also include validated data on total energy intake and expenditure and include them as covariants in the model. Large-scale long-term prospective studies studying BMI change as a continuous variable would also be valuable for exploring these ideas further.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—HK and GEF: designed and conducted the research and wrote the paper; JIL, AM, and MH: analyzed the data and performed the statistical analysis; GEF: had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: AHS-2, Adventist Health Study 2; HHF, Hospital History Form; HHF4, fourth biennial Hospital History Form.

References

- 1.Visscher TL, Seidell JC. The public health impact of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health 2001;22:355–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dutton GR, Kim Y, Jacobs DR Jr., Li X, Loria CM, Reis JP, Carnethon M, Durant NH, Gordon-Larsen P, Shikany JM, et al. 25-year weight gain in a racially balanced sample of U.S. adults: the CARDIA study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24:1962–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roos V, Elmstahl S, Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J, Lind L. Metabolic syndrome development during aging with special reference to obesity without the metabolic syndrome. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2017;15:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speechly DP, Buffenstein R. Greater appetite control associated with an increased frequency of eating in lean males. Appetite 1999;33:285–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keast DR, Nicklas TA, O’Neil CE. Snacking is associated with reduced risk of overweight and reduced abdominal obesity in adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:428–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Heijden AA, Hu FB, Rimm EB, van Dam RM. A prospective study of breakfast consumption and weight gain among U.S. men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howarth NC, Huang TT, Roberts SB, Lin BH, McCrory MA. Eating patterns and dietary composition in relation to BMI in younger and older adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koopman KE, Caan MW, Nederveen AJ, Pels A, Ackermans MT, Fliers E, la Fleur SE, Serlie MJ. Hypercaloric diets with increased meal frequency, but not meal size, increase intrahepatic triglycerides: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 2014;60:545–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mekary RA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, van Dam RM, Hu FB. Eating patterns and type 2 diabetes risk in men: breakfast omission, eating frequency, and snacking. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:1182–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mekary RA, Giovannucci E, Cahill L, Willett WC, van Dam RM, Hu FB. Eating patterns and type 2 diabetes risk in older women: breakfast consumption and eating frequency. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:436–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson N, Story M. A review of snacking patterns among children and adolescents: what are the implications of snacking for weight status? Child Obes 2013;9:104–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duval K, Strychar I, Cyr MJ, Prud’homme D, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Doucet E. Physical activity is a confounding factor of the relation between eating frequency and body composition. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:1200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohkawara K, Cornier MA, Kohrt WM, Melanson EL. Effects of increased meal frequency on fat oxidation and perceived hunger. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattson MP. Energy intake, meal frequency, and health: a neurobiological perspective. Annu Rev Nutr 2005;25:237–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anson RM, Guo Z, de Cabo R, Iyun T, Rios M, Hagepanos A, Ingram DK, Lane MA, Mattson MP. Intermittent fasting dissociates beneficial effects of dietary restriction on glucose metabolism and neuronal resistance to injury from calorie intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:6216–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, DiTacchio L, Bushong EA, Gill S, Leblanc M, Chaix A, Joens M, Fitzpatrick JA, et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab 2012;15:848–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherman H, Genzer Y, Cohen R, Chapnik N, Madar Z, Froy O. Timed high-fat diet resets circadian metabolism and prevents obesity. FASEB J 2012;26:3493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen CR, Hagemann I, Bock T, Buschard K. Intermittent feeding and fasting reduces diabetes incidence in BB rats. Autoimmunity 1999;30:243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anson RM, Jones B, de Cabod R. The diet restriction paradigm: a brief review of the effects of every-other-day feeding. Age (Dordr) 2005;27:17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang ZQ, Bell-Farrow AD, Sonntag W, Cefalu WT. Effect of age and caloric restriction on insulin receptor binding and glucose transporter levels in aging rats. Exp Gerontol 1997;32:671–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodrick CL, Ingram DK, Reynolds MA, Freeman JR, Cider NL. Effects of intermittent feeding upon growth and life span in rats. Gerontology 1982;28:233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raynor HA, Goff MR, Poole SA, Chen G. Eating frequency, food intake, and weight: a systematic review of human and animal experimental studies. Front Nutr 2015;2:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arciero PJ, Ormsbee MJ, Gentile CL, Nindl BC, Brestoff JR, Ruby M. Increased protein intake and meal frequency reduces abdominal fat during energy balance and energy deficit. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21:1357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers EF, Khoo CS, Murphy W, Steiber A, Agarwal S. A critical assessment of research needs identified by the dietary guidelines committees from 1980 to 2010. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:957–71.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garaulet M, Gómez-Abellán P, Alburquerque-Béjar JJ, Lee YC, Ordovs JM, Scheer FA. Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:604–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruge T, Hodson L, Cheeseman J, Dennis AL, Fielding BA, Humphreys SM, Frayn KN, Karpe F. Fasted to fed trafficking of fatty acids in human adipose tissue reveals a novel regulatory step for enhanced fat storage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:1781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purslow LR, Sandhu MS, Forouhi N, Young EH, Luben RN, Welch AA, Khaw KT, Bingham SA, Wareham NJ. Energy intake at breakfast and weight change: prospective study of 6,764 middle-aged men and women. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:188–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Timlin MT, Pereira MA. Breakfast frequency and quality in the etiology of adult obesity and chronic diseases. Nutr Rev 2007;65:268–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tani Y, Asakura K, Sasaki S, Hirota N, Notsu A, Todoriki H, Miura A, Fukui M, Date C. Higher proportion of total and fat energy intake during the morning may reduce absolute intake of energy within the day. An observational study in free-living Japanese adults. Appetite 2015;92:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.USDA. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington (DC): Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butler TL, Fraser GE, Beeson WL, Knutsen SF, Herring RP, Chan J, Sabate J, Montgomery S, Haddad E, Preston-Martin S, et al. Cohort profile: the Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2). Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bes-Rastrollo M, Sabaté J, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Fraser GE. Validation of self-reported anthropometrics in the adventist health study 2. BMC Public Health 2011;11:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaceldo-Siegl K, Knutsen SF, Sabate J, Beeson WL, Chan J, Herring RP, Butler TL, Haddad E, Bennett H, Montgomery S, et al. Validation of nutrient intake using an FFQ and repeated 24 h recalls in black and white subjects of the Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2). Public Health Nutr 2010;13:812–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartmann C, Siegrist M, van der Horst K. Snack frequency: associations with healthy and unhealthy food choices. Public Health Nutr 2013;16:1487–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yannakoulia M, Melistas L, Solomou E, Yiannakouris N. Association of eating frequency with body fatness in pre- and postmenopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma Y, Bertone ER, Stanek EJ III, Reed GW, Hebert JR, Cohen NL, Merriam PA, Ockene IS. Association between eating patterns and obesity in a free-living US adult population. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odegaard AO, Jacobs DR Jr., Steffen LM, Van Horn L, Ludwig DS, Pereira MA. Breakfast frequency and development of metabolic risk. Diabetes Care 2013;36:3100–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jakubowicz D, Barnea M, Wainstein J, Froy O. High caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:2504–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keim NL, Van Loan MD, Horn WF, Barbieri TF, Mayclin PL. Weight loss is greater with consumption of large morning meals and fat-free mass is preserved with large evening meals in women on a controlled weight reduction regimen. J Nutr 1997;127:75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosell M, Appleby P, Spencer E, Key T. Weight gain over 5 years in 21,966 meat-eating, fish-eating, vegetarian, and vegan men and women in EPIC-Oxford. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayes A, Gearon E, Backholer K, Bauman A, Peeters A. Age-specific changes in BMI and BMI distribution among Australian adults using cross-sectional surveys from 1980 to 2008. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:1209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reas DL, Nygard JF, Svensson E, Sorensen T, Sandanger I. Changes in body mass index by age, gender, and socio-economic status among a cohort of Norwegian men and women (1990–2001). BMC Public Health 2007;7:269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lilja M, Eliasson M, Stegmayr B, Olsson T, Soderberg S. Trends in obesity and its distribution: data from the Northern Sweden MONICA Survey, 1986–2004. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1120–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheer FA, Morris CJ, Shea SA. The internal circadian clock increases hunger and appetite in the evening independent of food intake and other behaviors. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:421–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jakubowicz D, Froy O, Wainstein J, Boaz M. Meal timing and composition influence ghrelin levels, appetite scores and weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults. Steroids 2012;77:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solomon TP, Chambers ES, Jeukendrup AE, Toogood AA, Blannin AK. The effect of feeding frequency on insulin and ghrelin responses in human subjects. Br J Nutr 2008;100:810–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garaulet M, Madrid JA. Chronobiological aspects of nutrition, metabolic syndrome and obesity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2010;62:967–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Theorell-Haglöw J, Lindberg E. Sleep duration and obesity in adults: what are the connections? Curr Obes Rep 2016;5:333–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capers PL, Fobian AD, Kaiser KA, Borah R, Allison DB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of the impact of sleep duration on adiposity and components of energy balance. Obes Rev 2015;16:771–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu T, Fu O, Yao L, Sun L, Zhuge F, Fu Z. Differential responses of peripheral circadian clocks to a short-term feeding stimulus. Mol Biol Rep 2012;39:9783–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawakami Y, Yamanaka-Okumura H, Sakuma M, Mori Y, Adachi C, Matsumoto Y, Sato T, Yamamoto H, Taketani Y, Katayama T, et al. Gene expression profiling in peripheral white blood cells in response to the intake of food with different glycemic index using a DNA microarray. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics 2013;6:154–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Are oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways mediators of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction? Diabetes 2003;52:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pereira MA, Erickson E, McKee P, Schrankler K, Raatz SK, Lytle LA, Pellegrini AD. Breakfast frequency and quality may affect glycemia and appetite in adults and children. J Nutr 2011;141:163–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Betts JA, Richardson JD, Chowdhury EA, Holman GD, Tsintzas K, Thompson D. The causal role of breakfast in energy balance and health: a randomized controlled trial in lean adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:539–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bandín C, Scheer FA, Luque AJ, Ávila-Gandía V, Zamora S, Madrid JA, Gómez-Abellan P, Garaulet M. Meal timing affects glucose tolerance, substrate oxidation and circadian-related variables: a randomized, crossover trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:828–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]