Abstract

Recent studies projecting future climate change impacts on forests mainly consider either the effects of climate change on productivity or on disturbances. However, productivity and disturbances are intrinsically linked because 1) disturbances directly affect forest productivity (e.g. via a reduction in leaf area, growing stock or resource-use efficiency), and 2) disturbance susceptibility is often coupled to a certain development phase of the forest with productivity determining the time a forest is in this specific phase of susceptibility. The objective of this paper is to provide an overview of forest productivity changes in different forest regions in Europe under climate change, and partition these changes into effects induced by climate change alone and by climate change and disturbances. We present projections of climate change impacts on forest productivity from state-of-the-art forest models that dynamically simulate forest productivity and the effects of the main European disturbance agents (fire, storm, insects), driven by the same climate scenario in seven forest case studies along a large climatic gradient throughout Europe. Our study shows that, in most cases, including disturbances in the simulations exaggerate ongoing productivity declines or cancel out productivity gains in response to climate change. In fewer cases, disturbances also increase productivity or buffer climate-change induced productivity losses, e.g. because low severity fires can alleviate resource competition and increase fertilization. Even though our results cannot simply be extrapolated to other types of forests and disturbances, we argue that it is necessary to interpret climate change-induced productivity and disturbance changes jointly to capture the full range of climate change impacts on forests and to plan adaptation measures.

Keywords: fire, forest models, forest productivity-disturbances-climate change interactions, insects, storms, trade-offs

1. Introduction

In the 20th century, forest productivity in Europe has increased (Spiecker et al 1996, Boisvenue and Running 2006). Simultaneously, damage from disturbances, i.e. discrete events destroying forest biomass, has increased as well (Schelhaas et al 2003, Seidl et al 2014). Both trends are partly associated with a changing climate (Boisvenue and Running 2006, Seidl et al 2011), and future projections mostly agree on continued changes in forest productivity (Wamelink et al 2009, Reyer et al 2014) and disturbances (e.g. Lindner et al 2010, Seidl et al 2014) due to ongoing climate change.

However, with a few, recent exceptions (e.g. Zubizareta Gerendiain et al 2017) most studies projecting future climate change impacts on forests usually only consider either the effects of climate change on productivity (e.g. Kellomäki et al 2008, Wamelink et al 2009, Reyer et al 2014, Reyer 2015) or on disturbances (e.g. Jönsson et al 2009, Bentz et al 2010, Westerling et al 2011, Subramanian et al 2015). However, both forest productivity and susceptibility to disturbances change dynamically over forest development as affected by environmental (climate, site) conditions (Urban et al 1987, Gower et al 1996, Ryan et al 1997, Netherer and Nopp-Mayr 2005, Peltola et al 2010, Thom et al 2013, Hart et al 2015).

Furthermore, productivity and disturbance are intrinsically linked: 1) disturbances directly affect forest productivity, e.g. through a reduced ability of the ecosystem to capture resources (e.g. lowered leaf area) or a decreased ability to utilize them (Peters et al 2013), and 2) disturbance susceptibility is often coupled to a specific development phase of the forest (Dale et al 2000, White and Jentsch 2001), and productivity determines the time a forest remains in this specific phase of susceptibility. For example, the probability of wind damage is strongly associated with tree height and species (Peltola et al 1999, Cucchi et al 2005, Gardiner et al 2010, Albrecht et al 2012, Zubizareta Gerendiain et al 2017), and forests that are more productive may reach critical heights earlier, increasing their susceptibility to wind damage (Blennow et al 2010a, 2010b). In the case of forest fires, it is widely accepted that an increase of productivity implies a higher rate of fuel build-up and subsequently higher fire hazard. However, in managed, even-aged forests, younger, denser forest stands are more susceptible to forest fires (González et al 2007, Botequim et al 2013, Marques et al 2012) and higher productivity may enable them to grow out of this susceptible state faster (Schwilk and Ackerly 2001, Fonda 2001, Keeley et al 2011).

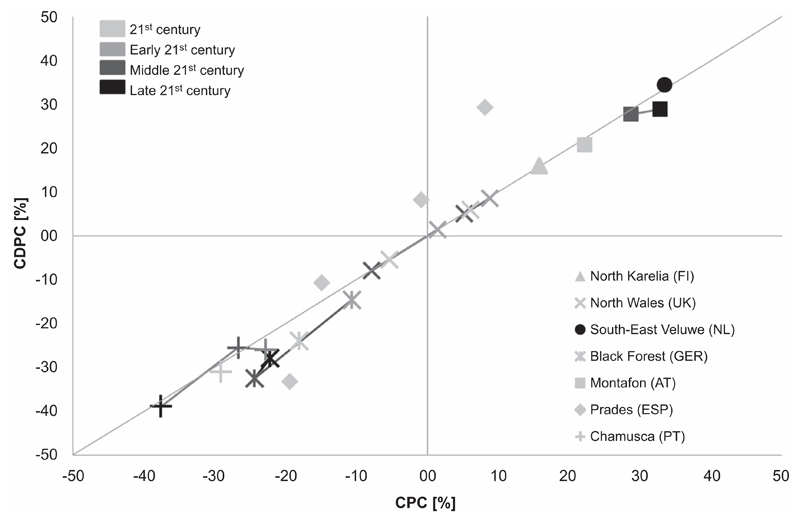

Here we compare the ‘climate-related productivity change’ (CPC), i.e. the change in forest productivity induced solely by climate change over a specific time period relative to a baseline period, to the ‘climate- and disturbance-related productivity change’ (CDPC), i.e. the change in forest productivity resulting from the joint effects of climate change and disturbances over the same time period relative to a baseline period including disturbances. The objective of this paper is to provide an overview of forest productivity changes in different forests in Europe under climate change, and partition these changes into effects induced by climate change alone and by climate change and disturbances.

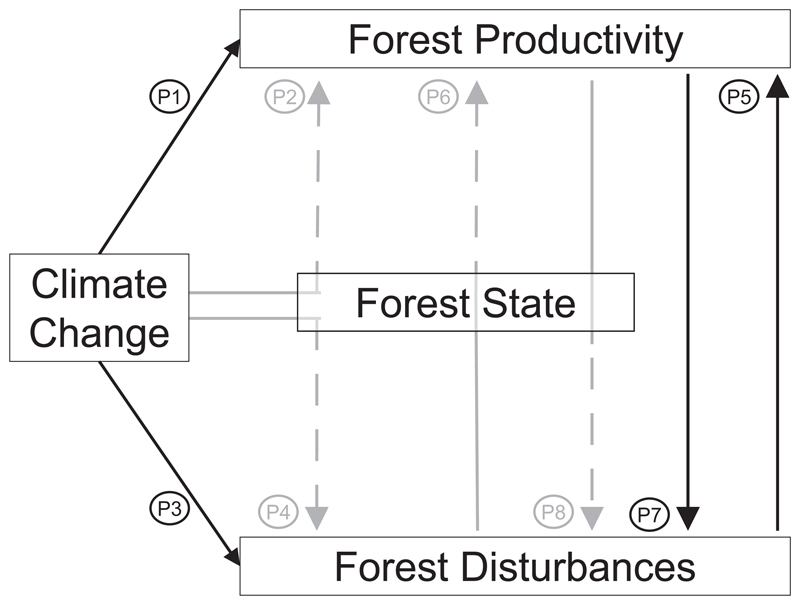

We present projections of CPC and CDPC from state-of-the-art forest models (table 1) that dynamically simulate forest productivity and the main European disturbance agents (fire, storm, insects), driven by the same climate scenario in seven forest case studies over a large climatic gradient throughout Europe. We classify these models based on a conceptual framework of different pathways of forest productivity-disturbances-climate change interactions (figure 1, table 2) and use them to test how climate change-induced productivity changes are interacting with simultaneously changing disturbances.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of the forest case studies. NTFP = Non-timber forest products.

| Country | Region | Area | Disturbance | Main ecosystem services | Tree species | Productivity Variable | Models | References introducing the forest region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | North Karelia | 950 ha | Wind | Timber, Bioenergy, Recreation, Biodiversity, NTFPs | Picea abies, Pinus sylvestris, Betula pendula, Betula pubescens | Mean Annual Timber Yield (m3 ha−1 yr−1) | Monsua | Zubizarreta-Gerendiain et al (2016, 2017) |

| UK | North Wales | 11500 ha | Wind | Timber, Recreation, Biodiversity | Picea sitchensis, Picea abies, Pinus sylvestris, Betula pubescens, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Pinus contorta, Larix kaempferi, Quercus petraea | Biomass production (t ha−1 yr−1) | MOTIVE8 simulation using ESC, ForestGALESb | Ray et al (2015) |

| Netherlands | South-East Veluwe | 1 ha (typical stand) | Wind | Conservation of natural and cultural history, Timber, Recreation | Pseudotsuga menziesii | Mean Annual Growth (m3 ha−1 yr−1) | ForGEMc, mechanical windthrow module based on HWINDb | Hengeveld et al (2015), Kramer et al (2006) |

| Germany | Black Forest | 1260 ha | Bark Beetle | Timber, Biodiversity, Recreation | Picea abies, Fagus sylvatica, Abies alba, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Quercus petreae, 25 others. | Biomass production (t−1 ha−1 yr−1) | LandClimd | Temperli et al (2012, 2013) |

| Austria | Montafon | 215 ha | Bark Beetle | Timber, Protection | Picea abies, Abies alba, Fagus sylvatica, Acer pseudoplatanus, Sorbus aucuparia, Alnus incana, Alnus alnobetula | Net Primary Production (kgC−1 ha−1 yr−1) | PICUS v1.5e | Maroschek et al (2015) |

| Spain | Prades | 4 typical stands, 1 ha each | Fire | Small-scale forestry, Recreation, NTFPs | Pinus sylvestris | Net Primary Production (Mg−1 ha yr−1) | GOTILWA+ f and adjusted fire modelg | Sabaté et al (2002) |

| Portugal | Chamusca | 483 ha | Fire | Pulp and Paper | Eucalyptus globulus | Current Annual Growth (m3 ha−1 yr−1) | Glob3PGh and management optimizeri | Palma et al (2015) |

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of interactions between climate change, forest productivity and forest disturbances. Solid, black arrows indicate direct effects; dashed arrows in gray indicate indirect effects mediated through effects on the state of the forests. P1–P8 refer to interaction pathways described in the text.

Table 2.

Classification of the models used in this study according to the productivity-disturbances-climate change interaction pathways specified in the conceptual framework shown in figure 1.

| Model | Climate change effect on productivity | Climate change effect on disturbances | Disturbance effect on productivity | Productivity effects on disturbance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct (P1) | Indirect (P2) | Direct (P3) | Indirect (P4) | Direct (P5) | Indirect (P6) | Direct (P7) | Indirect (P8) | |

| Monsu | Species- and site-specific scaling of growth functions/site index according to simulations with physiological model | Change in species composition | Na | Probability of wind damage increases by 0.17% per year due to gradual increase of unfrozen soil period | Wind damage reduces forest productivity when windthrown trees are not harvested | Non-optimal harvesting time may reduce forest productivity via effects on forest structure | Na | Changes in dominance of different tree species, stocking (stand density), height and height/diameter ratio of trees. |

| MOTIVE8 | Temperature, precipitation and moisture deficit affect growth | Na | Na | Na | Wind damage before planned harvest date reduces forest productivity | Harvesting before stands reach Maximum Mean Annual Increment to reduce wind risk reduces forest productivity as the full productive potential of the site is never reached | Na | Changes in height growth alter susceptibility to wind damage |

| ForGEM + mechanical windthrow module based on HWIND | Species- and site-specific scaling of growth functions/site index according to simulations with physiological model | Na | Na | Na | Removal of trees | Effect on forest structure | Na | Changes in height growth alter susceptibility to wind damage |

| LandClim | Temperature and precipitation affect growth | Change in species composition | Changes in temperature affect the reproduction rate of bark beetles | Bark beetle disturbance susceptibility depends on drought-stress, age and basal area share of Norway spruce as well as the windthrown spruce biomass | Bark beetle disturbance causes tree mortality decreasing forest productivity | Change in species composition | Na | Basal area share of Norway spruce influences bark beetle disturbance susceptibility |

| PICUS v1.5 | Temperature, precipitation, radiation and vapor pressure deficit affect growth | Temperature and precipitation affect tree species composition | Changes in temperature affect the reproductive rate of bark beetles | Bark beetle susceptibility depends on drought stress of host trees as well as host tree availability, basal area, and age | Disturbances reduce leaf area and thus the radiation absorbed, which in turn affects productivity | Change in species composition | Na | Stand structure (age, Norway spruce share) influences bark beetle disturbance susceptibility |

| GOTILWA + and adjusted fire model | Temperature and precipitation affect growth | Na | Climate change affects the predicted annual fire occurrence probability | Drought-stressed trees are more susceptible to die after fire | Mortality and a temporal (1 to 3 years) decrease in tree growth | Ash fertilization; a ‘thinning from bellow effect’ of fire reducing competition for water | Na | Probability of fire and post-fire mortality are estimated according to the structure of the forest |

| Glob3PG and management optimization method | Temperature and precipitation affect growth | Na | Climate change leads to 5% decrease in fire return interval and 5% increase in area burnt | Na | Increased fire frequency and increased affected area destroy biomass | Periodical reductions in area productivity due to fire, changes optimum management in each management unit attempting to respect flow constraints | Na | Na |

2. Conceptual framework of forest productivity-disturbances-climate change interactions

Conceptually, the interaction between climate change, forest productivity and disturbances can take eight pathways (P1–P8 in the following) which we characterize as ‘direct’ if the interaction is established through a clear cause-effect relationship while we use ‘indirect’ if the interaction is mediated through changes in the forest state (figure 1). According to this logic, the influence of climate change on productivity and disturbances can take four pathways (P1–P4) just like the interaction between forest productivity and disturbances (P5–P8).

A changing climate directly influences key productivity processes such as photosynthesis or respiration (Ryan 1991, Bonan 2008) (P1), but has also indirect effects through changes in soil characteristics or changes in species composition (Bolte et al 2010) (P2). In turn, disturbances may be directly affected by climate change, e.g. through higher wind speeds and changing storm tracks (Shaw et al 2016) or higher temperatures increasing bark beetle reproduction rates (Wermelinger and Seifert 1999, Mitton and Ferrenberg 2012) (P3), but could also experience indirect effects such as increasing susceptibility to wind damage because of unfrozen soils (Kellomäki et al 2010) (P4).

Likewise, disturbances may directly influence forest productivity by killing trees (e.g. Michaletz and Johnson 2007) or through more subtle effects of disturbances on productivity (P5). For example, insect defoliation may reduce the amount of absorbed photosynthetic active radiation, the carbon uptake, the stored carbohydrates and nitrogen remobilization, thus reducing overall productivity (Pinkard et al 2011) and stem growth (Jacquet et al 2012, 2013). Disturbances may also indirectly influence forest productivity by changing forest structure and composition (Bolte et al 2010, Perot et al 2013) (P6). For example, a disturbance-induced increase in tree species diversity can bolster forest productivity (Silva Pedro et al 2016). Productivity may also directly affect the susceptibility to disturbances (P7). For example, more productive trees may be more vital and hence better able to cope with insect attacks due to an increased availability of carbohydrates for defense (Wermelinger 2004, McDowell et al 2011). Changing productivity e.g. due to changing atmospheric CO2 concentrations may also influence leaf element stoichiometry and hence influence the palpability and nutritional value of leaves for herbivores (Ayres and Lombardero 2000, Netherer and Schopf 2010). Finally, changing productivity indirectly determines a forest’s susceptibility to disturbances by altering key structural features of a forest (P8). For example, simulation studies indicate that increasing productivity under climate change in Sweden leads to increasing height growth and tree heights which in turn increases the probability of wind damage (Blennow et al 2010a, 2010b).

3. Material and methods

The seven forest case studies studied here are located in North Karelia (Finland), North Wales (United Kingdom), the South-east Veluwe (The Netherlands), Black Forest (Germany), Montafon (Austria), Prades (Spain) and Chamusca (Portugal). They provide a wide range of ecosystem services to society, are shaped by different climatic, edaphic and socio-economic environments and are characterized by varying disturbance regimes (table 1, SOM1 (available at stacks.iop.org/ERL/12/034027/mmedia) cf. Fitzgerald and Lindner 2013, Reyer et al 2015). In each case study a specific forest model or differing chains of forest models were applied, utilizing the best available models for each system, and building on a large body of work on testing and evaluating these models for the respective ecosystems. We chose to use the best locally available models for each case study rather than a one-size-fits-all model in order to best capture the local ecosystem dynamics and disturbances, management legacies, species choices and responses to climate change. Consequently, the time periods analyzed and output indicators are not fully homogenized to account for constraints of respective models and local data availability (table 1, see SOM2 for details).

For each forest, four model simulations were carried out: one under baseline climate (B) and one including the effects of climate change on forest productivity (CC) to calculate CPC. Subsequently, these two simulations were repeated also accounting for the effects of disturbances (abbreviated BD and CCD respectively) to calculate CDPC. According to the framework developed in section 3, the simulations required to calculate CPC include the pathways P1 and/or P2 while the simulations for CDPC potentially include all pathways (P1–P8) if included in the model used in each case study (table 2). The climate change simulations all used forcing from the A1B emission scenario from the ENSEMBLES project (van der Linden and Mitchell 2009), and were bias-corrected and downscaled to the respective case study at a 100 m spatial resolution (Zimmermann 2010). All simulations assumed business-as-usual management (two different ones in the Prades region) typical for the region, and expressed changes in productivity using slightly different indicators such as net primary production or mean annual growth, depending on the model applied. More details about the forests, modeling approaches and data sources can be found in table 1 and SOM1-2. In the following, we briefly describe how, in each forest, productivity and disturbances are affected by climate change, following the conceptual framework outlined above (table 2). We then synthesize results from the case studies across the different indicators of forest productivity and disturbances used in each study by comparing CPC and CDPC.

3.1. Influence of climate change on productivity and disturbances in the European forest case studies

3.1.1. North Karelia (FI)

In the MONSU simulation system, climate change impacts on productivity were simulated by adjusting species- and site-specific growth functions with data from simulations by a physiological model (Pukkala and Kellomaki 2012). Under a changing climate, the probability of wind damage was expected to increase by 0.17% per year to account for an increase of the unfrozen soil period (Kellomäki et al 2010), but no change in wind climate was assumed (Gregow 2013). Productivity changes alter the dominance of different tree species, stocking (stand density), height and height/diameter ratio of trees all of which affect the critical values of wind speed that determine wind damage.

3.1.2. North Wales (UK)

In the ‘MOTIVE8’ model framework (Ray et al 2015), temperature, precipitation and moisture deficit affect forest growth. Climate change impacts on forest biomass production were simulated through species- specific scaling of site index. A changing growth rate affects the age at which the trees become vulnerable to windthrow. There was no clear signal of climate change on wind climate in this region, hence the same wind climate as for the past was assumed.

3.1.3. South-east Veluwe (NL)

In the ForGEM model (Schelhaas et al 2007), climate change impacts on productivity were mimicked through species-specific scaling of site index according to simulations with a physiological model (Reyer et al 2014), see also (Schelhaas et al 2015). Since the parameters of the height growth curve are linked to the site class, increasing productivity also means an increase in height growth leading to higher susceptibility to wind damage. There was no clear signal of climate change on wind climate in this case study, hence the historic wind climate was used.

3.1.4. Black forest (GER)

In the LandClim model, temperature and precipitation affect productivity according to response functions and through changes in species dominance (Schumacher et al 2004). Changes in temperature affect the reproduction rate of bark beetles. Moreover, bark beetle disturbances depend on drought-stress, age and basal area share of Norway spruce as well as on windthrown spruce biomass (Temperli et al 2013). They lead to changes in bark beetle population dynamics. Moreover, LandClim accounts for the beetle-outbreak-triggering effect of windthrow by increased forest susceptibility to bark beetles in the vicinity (<200 m) of windthrow patches and in relation to the windthrown spruce biomass (Wichmann and Ravn 2001). For the simulations considered in this study, the frequency of and area of stochastically simulated windthrow events was assumed to remain constant under climate change, while bark beetles responded dynamically to a changing climate.

3.1.5. Montafon (AT)

In the PICUS v1.5 model, temperature and precipitation affect productivity according to a radiation use efficiency model of stand growth as well as through changes in species dominance (Lexer and Hönninger 2001, Seidl et al 2005, Seidl et al 2007). Changes in temperature also affect the reproduction rate of bark beetles. Moreover, the bark beetle susceptibility of Norway spruce stands depends on stand age, basal area, host tree share, and drought stress of potential host trees (Seidl et al 2007).

3.1.6. Prades (ESP)

In the GOTILWA+ model (Gracia et al 1999), temperature and precipitation affect productivity by changing the photosynthetic carbon uptake. Climate change affects the predicted annual fire occurrence probability and fuel moisture. Moreover, drought-stressed trees with reduced amounts of mobile carbohydrates are more likely to die after fire. Changes in productivity modify forest structure and fuel loads and therefore also fire occurrence and severity since the probability of fire is estimated each year, according to the state of the forest (stand basal area, mean and degree of evenness of tree size) and the climatic conditions affecting fuel moisture. Once a fire occurs, it causes mortality plus a temporal (1–3 years) decrease in tree growth (Valor et al 2013). The decrease in tree growth can be compensated by ash fertilization or a ‘thinning from below effect’ of fire, depending on fire intensity and structure of the stand. The ‘thinning from below effect’ is in most cases a result of low to medium severity fires (non-stand-replacing fires) that modify stand structure and may reduce tree competition for water resources.

3.1.7. Chamusca (PT)

In the Glob3PG model (Tomé et al 2004), temperature and precipitation affect productivity directly through modification of canopy quantum efficiency and, in the case of precipitation, by affecting available soil water that controls biomass allocation to roots. Climate change was assumed to lead to 5% decrease in fire return interval and 5% increase in area burnt.

4. Results

4.1. Climate change impacts on forest productivity with and without including effects of disturbances

In North Karelia, South-East Veluwe and Montafon, CPC ranged from +15.8% to +33.6% (figure 2, table SOM2). The productivity increases in North Wales were smaller and turned negative for the drier site. In the Black Forest, CPC was negative and ranged between −10.6% and −24.4%, depending on the time period considered. In the two southern European forest case studies, CPC was mostly negative (−22.8% to −37.6% in Chamusca and −0.8% to −19.4% in Prades) with the exception of forests on deep soils in the Prades region, which showed a small productivity increase (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative climate change-induced productivity changes with (CDPC) and without (CPC) accounting for disturbances in different forest case studies in Europe. Legend details: 21st century = long-term average over the entire 21st century, Early 21st century = early 21st century average (ca 2000–2040), Middle 21st century = mid-21st century average (ca 2040–2070), Late 21st century = late 21st century average (ca 2070–2100). The exact dates vary slightly according to the different models and are listed in table SOM2. Symbols linked by lines indicate a temporal sequence of results. The horizontal and vertical lines indicate ‘no change’ and the diagonal line is a 1:1 line. Points above the 1:1 line indicate increased productivity as a result of disturbance, while points below it illustrate cases where disturbances decrease productivity.

These patterns remained largely consistent when disturbances were included in the simulations (figure 2) with the exception of simulations for the unmanaged Prades forest on deep soils. This forest’s CDPC amounted to +8.2% opposed to a slightly negative CPC (−0.8%) because positive feedbacks from fire caused a release from competition and a fertilization effect.

However, even if the patterns remained the same in most cases, including disturbances had negative effects on productivity, either by reducing positive CPCs or by exacerbating negative CPCs (figure 2). These decreases were rather small and range between −0.05% and −14.0%. In a few cases, including disturbances in the simulations increased positive CDCs but only in the managed Prades forest on deep soils this amounted to a tangible change of +21.1%. In some of the simulations for Prades (unmanaged forest on deep soils and managed forest on shallow soils) and Chamusca (simulation for 2041–2070) regions the negative climate change effects were partly alleviated by including disturbances. These positive effects of disturbances ranged between +1.1% to +9.0%.

For those simulations for which the effects of climate change and disturbances on productivity were studied for more than two time periods, interesting temporal patterns emerged. In the Black Forest, mid-century CDPC was lowest while in Chamusca, the mid-century CDPC was slightly higher than the early- or late 21st century simulations.

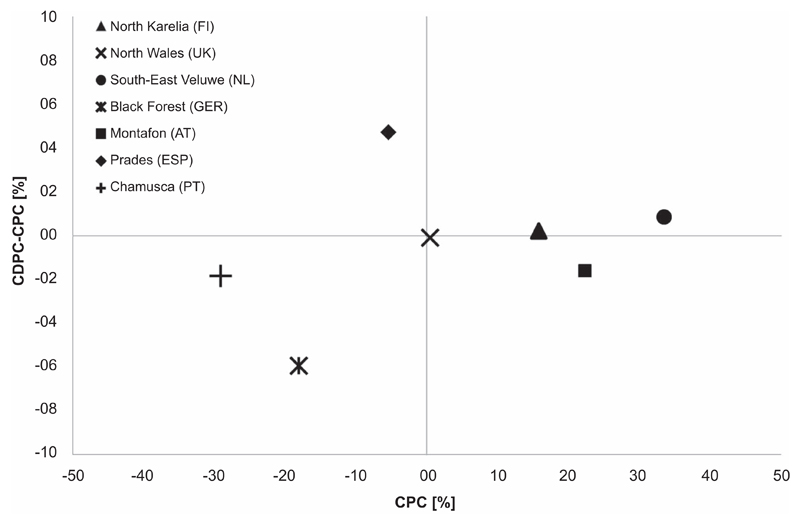

To further test how CPC and CDPC interact, we only considered the difference of CPC and CDPC of those data points that represent the longest possible simulation period for each forest case study (figure 3). This analysis showed that in those forests where CPC was negative (left quadrants in figure 3, Chamusca and Black Forest), disturbances were exacerbating productivity losses. In Prades, disturbances alleviated productivity losses even though the CDPC remained negative. For North Wales and Montafon for which CPCs were positive (right quadrants in figure 3), disturbances were decreasing the positive CPCs but the CDPC remained positive. For the Southern Veluwe and North Karelia, the CDPC was slightly positive because the storm damage in these forests reduced competition among the remaining trees.

Figure 3.

Difference of productivity change induced by climate change and disturbances (CDPC) and climate change only induced productivity changes (CPC) over climate change only induced productivity changes (CPC) for the longest available simulations in each forest case study. Note that the data for Prades and North Wales are the average over the forests stands as shown in table SOM2.

5. Discussion

This paper shows that climate change-induced productivity changes and disturbances interact in different forests in Europe. In most cases, including disturbances in the simulations clearly exaggerate ongoing productivity declines or cancel out climate change-induced productivity gains. In fewer cases and in some regions only, disturbances also increase productivity or alleviate climate-change induced productivity losses. Only in rather specific situations such as for Prades, they are a real ‘game changer’, turning a climate change-induced productivity loss into a productivity gain. However, in general, the contribution of disturbances to productivity changes compared to those induced by climate change alone is rather small. It is important to note though, that our focus on productivity means that we base the interpretation of our findings on long-term averages (Blennow et al 2014) while the higher variability that comes with increased disturbances (as an unplanned event) might still increase management complexity in the short term. Even though this study does not allow us to quantify the individual contribution of the different productivity-disturbances-climate change interaction pathways, we show that indeed such interactions are operating in very different forests across Europe.

5.1. Climate change impacts on forest productivity with and without including effects of disturbances

The general trends of increasing CPC in North Karelia, South-East Veluwe and Montafon turning negative if water supply is limited such as in North Wales found in this study are consistent with climate impacts reported in earlier modelling studies for temperate and boreal forests (see Reyer 2015). The rather strong productivity decrease in the Black Forest can be explained by the dominance of Norway Spruce plantations that are very susceptible to climate change (Hanewinkel et al 2010, 2013). The decreases in productivity in the two southern European forest case studies (Chamusca and Prades) are also consistent with other modelling studies from Southern Europe (Sabaté et al 2002, Schröter et al 2005).

Our results reveal interesting temporal patterns of CDPC. The mid-century peak in negative CDPC in the Black Forest region can be explained by two mechanisms: 1) at this time, most of the forest is in a susceptible stage and 2) the damage is so high that later, even though the climate change signal is stronger, less forest area is actually damaged. The combined effects of climate change and bark beetle disturbance lead to a replacement of the beetle’s host species Norway spruce with deciduous and more drought adapted tree species. Similar processes have been found to influence the projected long-term carbon stocks in Swiss forests (Manusch et al 2014). Moreover, when considering only the longest possible simulation period for each forest region, the negative, additional effect of disturbances is rather small (maximum −5.9% in the Black Forest, figure 3) which is remarkable given the strong changes in forest composition and structure as well as ecosystem services provision going along with such changes (Temperli et al 2012, 2013).

5.2. Direct and indirect pathways of productivity-disturbance interactions under climate change

The classification of the models based on the conceptual framework of climate-productivity-disturbance interactions (figure 1) demonstrates that most models are representing both direct and indirect effects of disturbances on productivity (P5–P6, table 2). These models also include indirect effects of changes in productivity on disturbances (P8). However, no model covers all possible pathways and especially the direct effects of changes in productivity on disturbances are not explicitly represented in the set of models used here (P7), possibly because these models do not necessarily operate at the level of process detail required to capture these direct effects, e.g. by excluding leaf element stoichiometry or the role of carbohydrates in plant defense. Moreover, the models mostly cover one or two processes per pathway even though there might be more (e.g. bark beetle reproduction is affected by temperature in LandClim and PICUS but other climatic factors such as drought also play a role (Netherer and Schopf 2010). As our knowledge of these effects evolves the inclusion of such processes into forest models will become more important in the future. It is also important to note that some of the models used in this study also include ‘adaptive management responses’. The management changes according to the disturbance-productivity interactions under climate change by optimizing management to maintain stable resource flows (in Chamusca) or by reducing harvesting age to lower wind risks (in North Wales). More systematic studies of the effect and potential of management interventions to alleviate the effects of changing climate and disturbance regimes on forest productivity are hence needed.

Moreover, there is evidence for many more direct and indirect pathways of productivity-disturbance interactions beyond the ones discussed here (Seidl et al 2012). These will require attention in future model applications. Likewise, future studies should also focus on disentangling the importance of the different pathways and their spatial and temporal interactions. Furthermore, it is important to note that disturbances can have a wide variety of other impacts on forests and the services they provide for society beyond changing productivity (Andersson et al 2015, Thom and Seidl 2016, Zubizarreta-Gerendiain et al 2017).

5.3. Limitations and uncertainties

One key limitation of our study is that we are relying only on one emission scenario from one climate model in each of the forest case studies, even though climate impacts differ in between emission scenarios and within emission scenarios when different climate models are considered (Reyer et al 2014). Therefore, our simulations do not provide a systematic assessment of the uncertainties induced by climate models and future socio-economic development, but rather provide a first look into how climate change, disturbances and productivity changes are interacting. Moreover, the simulation results presented in this study focus on one main disturbance agent in each forest region to be affected by climate change even though forest productivity may be strongly affected by the occurrence of multiple, compounding and interacting disturbances (Radeloff et al 2000, Dale et al 2001, Bigler et al 2005, Hanewinkel et al 2008, Temperli et al 2013, Temperli et al 2015). Wind-blown or drought-stressed trees for example provide breeding material for insects that then may even attack fully vigorous trees (e.g. Schroeder and Lindelöw 2002, Gaylord et al 2013). Newly created forest edges after a storm may expose formerly rather protected trees to subsequent storms. Thus, understanding the spatial and temporal interaction of disturbances and their interaction with changing productivity is another important research challenge (Andersson et al 2015, Seidl and Rammer 2016). Moreover, the models used in each forest case study are quite different in the way in which they incorporate the effects of climate change on productivity, and also their representation of disturbances. Therefore, comparing the impacts across different forests can only be done qualitatively, keeping in mind the differences in the models. Moreover, the forest case studies are themselves very different in terms of forest management, species choice etc which are all factors that determine the influence of climate change. Altogether, this means that more variation of the changes in forest productivity under climate change and disturbances than expressed by our results is to be expected. However, our results provide first indications of how climate change and disturbances may play out at larger spatial scales around our forest case studies and similar forest ecoregions.

Finally, this study has focused on the role of disturbances in particular. Future studies should aim at testing the interactions of all pathways of our conceptual framework to gain a full understanding of forest productivity-disturbances-climate change interactions. This could be achieved by developing and applying improved models of disturbance interactions based on experiments and observations of such interactions. Moreover, it would be necessary to study in greater depth whether our findings are consistent over different types of disturbances, stages of stand development, management regimes and soil conditions (which have proven to be very important in e.g. Prades). Such developments could then be integrated into larger-scale simulation models allowing upscaling from the case study level to the continental scale. However, it is important to consider that such larger–scale models will be limited in terms of the number of disturbances and potential interactions that can be included whenever the disturbances are not only resulting from large-scale driving forces (such as extreme heat events depending on planetary waves (Petoukhov et al 2016)) but also contingent on local site and forest conditions.

6. Conclusion

While the extrapolation of our case study-based results to other types of forests and disturbances requires caution, we argue that our findings have important implications for the assessment of climate change impacts on forest products and services in Europe. On the one hand, higher productivity in a future that is characterized by increasing disturbances may mean that more damage to forests may occur, especially if accompanied by higher standing volume stocks. On the other hand, reduced productivity may mean that less biomass is ‘available to be damaged’ but also that what is damaged is more valuable from a resource availability perspective. Therefore, it is necessary to interpret climate change-induced productivity and disturbance changes jointly to capture the full range of climate change impacts on forests and to plan adaptation. Likewise, these findings are important since currently many model studies, also those relying on models operating at larger spatial scales up to the global level, show that higher productivity will result in higher carbon storage and hence continued carbon uptake from the atmosphere even though the role of disturbances is only cursorily accounted for in many models.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available online

Acknowledgements

This study was initiated as part of the MOTIVE project funded by the Seventh Framework Program of the EC (Grant Agreement No. 226544) and benefitted further from the discussion carried out in the COST Action FP1304 PROFOUND as well as the Module E.8 of the IUFRO Task Force on ‘Climate Change and Forest Health’. CPOR acknowledges funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant no. 01LS1201A1). MJS and KK acknowledge funding from the strategic research programme KBIV ‘Sustainable spatial development of ecosystems, landscapes, seas and regions’, funded by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs. KK was additionally funded by the Knowledge Base project Resilient Forests (KB-29-009-003). RS acknowledges further support from the Austrian Science Fund FWF through START grant Y895-B25. HP acknowledges funding from the strategic research council of Academy of Finland for FORBIO project (no. 14970). The ISA-authors acknowledge funding from the CEF research Centre by project UID/AGR/00239/2013. NEZ acknowledges further support from Rafael O Wüest and from the Swiss Science Foundation SNF (grant #40FA40_158395). CTFC authors acknowledge funding from MINECO (Ref. RYC-2011-08983, RYC-2013-14262, AGL2015-67293-R MINECO/FEDER) and from CERCA Programme / Generalitat de Catalunya.

References

- Albrecht A, et al. Storm damage of Douglas-fir unexpectedly high compared to Norway spruce. Ann For Sci. 2012;70:195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M, Kellomäki S, Gardiner B, Blennow K. Life-style services and yield from south-Swedish forests adaptively managed against the risk of wind damage: a simulation study. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15:1489–500. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres MP, Lombardero MJ. Assessing the consequences of global change for forest disturbance from herbivores and pathogens. Sci Total Environ. 2000;262:263–86. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(00)00528-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentz BJ, et al. Climate change and Bark Beetles of the Western United States and Canada: direct and indirect effects. BioScience. 2010;60:602–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler C, Kulakowski D, Veblen TT. Multiple Disturbance Interactions and drought influence fire severity in Rocky Mountain subalpine forests. Ecology. 2005;86:3018–29. [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, Andersson M, Sallnäs O, et al. Climate change and the probability of wind damage in two Swedish forests. For Ecol Manage. 2010a;259:818–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, Andersson M, Bergh J, et al. Potential climate change impacts on the probability of wind damage in a south Swedish forest. Clim Change. 2010b;99:261–78. [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, et al. Understanding risk in forest ecosystem services: implications for effective risk management, communication and planning. Forestry. 2014;87:219–28. [Google Scholar]

- Boisvenue C, Running SW. Impacts of climate change on natural forest productivity—evidence since the middle of the 20th century. Glob Change Biol. 2006;12:862–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bolte A, et al. Climate change impacts on stand structure and competitive interactions in a southern Swedish spruce–beech forest. Eur J For Res. 2010;129:261–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bonan GB. Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science. 2008;320:1444–49. doi: 10.1126/science.1155121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botequim B, et al. Developing wildfire risk probability models for Eucalyptus globulus stands in Portugal. iForest—BiogeoSci For. 2013;6:217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Cucchi V, et al. Modelling the windthrow risk for simulated forest stands of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait) For Ecol Manage. 2005;213:184–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dale VH, et al. Climate change and forest disturbances. Bioscience. 2001;51:723–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dale VH, et al. The interplay between climate change, forests, and disturbances. Sci Total Environ. 2000;262:201–4. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(00)00522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J, Lindner L. Adapting to Climate Change in European Forests—Results of the MOTIVE Project. Sofia: Pensoft; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fonda RW. Burning characteristics of needles from eight pine species. Forest Sci. 2001;47:390–96. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalo J, et al. A decision support system for management planning of Eucalyptus plantations facing climate change. Ann For Sci. 2014;71:187–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner B, et al. Destructive Storms in European Forests: Past and Forthcoming Impacts. Bordeaux: European Forest Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner B, Peltola H, Kellomäki S. Comparison of two models for predicting the critical wind speeds required to damage coniferous trees. Ecol Model. 2000;129:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord ML, et al. Drought predisposes piñon–juniper woodlands to insect attacks and mortality. New Phytol. 2013;198:567–78. doi: 10.1111/nph.12174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González JR, et al. 2006 A fire probability model for forest stands in Catalonia (north-east Spain) Ann For Sci. 2006;63:169–76. [Google Scholar]

- González JR, et al. Predicting stand damage and tree survival in burned forests in Catalonia (North-East Spain) Ann For Sci. 2007;64:733–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gower ST, McMurtrie RE, Murty D. Aboveground net primary production decline with stand age: potential causes. Trends Ecol Evol. 1996;11:378–82. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia CA, et al. Ecology of Mediterranean Evergreen Oak Forest. Ecological Studies. Vol. 137. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1999. GOTILWA: an integrated model of water dynamics and forest growth; pp. 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Gregow H. Impacts of Strong Winds, Heavy Snow Loads and Soil Frost Conditions on the Risks to Forests in Northern Europe. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Meteorological Inst; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel M, et al. Climate change may cause severe loss in the economic value of European forest land. Nature Clim Change. 2013;3:203–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel M, et al. Seventy-seven years of natural disturbances in a mountain forest area the influence of storm, snow, and insect damage analysed with a long-term time series. Can J For Res. 2008;38:2249–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel M, Hummel S, Cullmann DA. Modelling and economic evaluation of forest biome shifts under climate change in Southwest Germany. For Ecol Manage. 2010;259:710–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hart SJ, et al. Negative feedbacks on Bark beetle outbreaks: widespread and severe spruce beetle infestation restricts subsequent infestation ed F Biondi. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen T, et al. Integrating the risk of wind damage into forest planning. For Ecol Manage. 2009;258:1567–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hengeveld GM, et al. The landscape-level effect of individual-owner adaptation to climate change in Dutch forests. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15:1515–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet J-S, et al. Pine growth response to processionary moth defoliation across a 40 year chronosequence. For Ecol Manage. 2013;293:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet J-S, Orazio C, Jactel H. Defoliation by processionary moth significantly reduces tree growth: a quantitative review. Ann For Sci. 2012;69:857–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson AM, et al. Spatio-temporal impact of climate change on the activity and voltinism of the spruce bark beetle, Ips typographus. Glob Change Biol. 2009;15:486–99. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JE, et al. Fire as an evolutionary pressure shaping plant traits. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:406–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellomäki S, et al. Model computations on the climate change effects on snow cover, soil moisture and soil frost in the boreal conditions over Finland. Silva Fennica. 2010;44:213–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kellomäki S, et al. Sensitivity of managed boreal forests in Finland to climate change, with implications for adaptive management. Phi Trans R Soc Lond B. 2008;363:2341–51. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer K, Groot Bruinderink GWTA, Prins HHT. Spatial interactions between ungulate herbivory and forest management. For Ecol Manage. 2006;226:238–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lexer MJ, Hönninger K. A modified 3D-patch model for spatially explicit simulation of vegetation composition in heterogeneous landscapes. Forest Ecol Manage. 2001;144:43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner M, et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For Ecol Manage. 2010;259:698–709. [Google Scholar]

- Manusch C, Bugmann H, Wolf A. The impact of climate change and its uncertainty on carbon storage in Switzerland. Reg Environ Change. 2014;14:1437–50. [Google Scholar]

- Maroschek M, Rammer W, Lexer MJ. Using a novel assessment framework to evaluate protective functions and timber production in Austrian mountain forests under climate change. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15:1543–55. [Google Scholar]

- Marques S, et al. Assessing wildfire occurrence probability in Pinus pinaster Ait. stands in Portugal. Forest Syst. 2012;21:111. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell NG, et al. The interdependence of mechanisms underlying climate-driven vegetation mortality. Trends Ecol Evol. 2011;26:523–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaletz ST, Johnson EA. How forest fires kill trees: a review of the fundamental biophysical processes. Scand J Forest Res. 2007;22:500–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mitton JB, Ferrenberg SM. Mountain Pine beetle develops an unprecedented summer generation in response to climate warming. Am Nat. 2012;179:E163–71. doi: 10.1086/665007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netherer S, Nopp-Mayr U. Predisposition assessment systems (PAS) as supportive tools in forest management— rating of site and stand-related hazards of bark beetle infestation in the High Tatra Mountains as an example for system application and verification. For Ecol Manage. 2005;207:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Netherer S, Schopf A. Potential effects of climate change on insect herbivores in European forests–General aspects and the pine processionary moth as specific example. For Ecol Manage. 2010;259:831–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll B, Hale S, Gardiner B, Peace A, Rayner B. ForestGALES: A Wind Risk Decision Support Tool For Forest Management in Britain. Edinburgh: Forestry Commission; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Palma JHN, et al. Adaptive management and debarking schedule optimization of Quercus suber L. stands under climate change: case study in Chamusca, Portugal. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15:1569–80. [Google Scholar]

- Peltola H, et al. A mechanistic model for assessing the risk of wind and snow damage to single trees and stands of Scots pine, Norway spruce, and birch. Can J For Res. 1999;29:647–61. [Google Scholar]

- Peltola H, et al. Impacts of climate change on timber production and regional risks of wind-induced damage to forests in Finland. For Ecol Manage. 2010;260:833–45. [Google Scholar]

- Perot T, Vallet P, Archaux F. Growth compensation in an oak–pine mixed forest following an outbreak of pine sawfly (Diprion pini) For Ecol Manage. 2013;295:155–61. [Google Scholar]

- Peters EB, et al. Influence of disturbance on temperate forest productivity. Ecosystems. 2013;16:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Petoukhov V, et al. Role of quasiresonant planetary wave dynamics in recent boreal spring-to-autumn extreme events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:6862–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606300113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkard EA, et al. Estimating forest net primary production under changing climate: adding pests into the equation. Tree Physiol. 2011;31:686–99. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpr054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukkala T. Dealing with ecological objectives in the Monsu planning system. Silva Lusitana. 2004;12:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pukkala T, Kellomaki S. Anticipatory vs adaptive optimization of stand management when tree growth and timber prices are stochastic. Forestry. 2012;85:463–72. [Google Scholar]

- Radeloff VC, Mladenoff DJ, Boyce MS. Effects of interacting disturbances on landscape patterns: budworm defoliation and salvage logging. Ecol Appl. 2000;10:233–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rammer W, et al. A web-based ToolBox approach to support adaptive forest management under climate change. Scand J Forest Res. 2014;29:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ray D, et al. Comparing the provision of ecosystem services in plantation forests under alternative climate change adaptation management options in Wales. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15:1501–13. [Google Scholar]

- Reyer C. Forest productivity under environmental change—a review of stand-scale modeling studies. Current Forestry Reports. 2015;1:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Reyer C, et al. Models for adaptive forest management. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15:1483–87. [Google Scholar]

- Reyer C, et al. Projections of regional changes in forest net primary productivity for different tree species in Europe driven by climate change and carbon dioxide. Ann For Sci. 2014;71:211–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M, Binkley D, Fownes JH. Age-related decline in forest productivity: pattern and process. Adv Ecol Res. 1997;27:213–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan MG. Effects of climate change on plant respiration. Ecol Appl. 1991;1:157–67. doi: 10.2307/1941808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté S, Gracia CA, Sánchez A. Likely effects of climate change on growth of Quercus ilex, Pinus halepensis, Pinus pinaster, Pinus sylvestris and Fagus sylvatica forests in the Mediterranean region. For Ecol Manage. 2002;162:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schelhaas M-J, et al. Alternative forest management strategies to account for climate change-induced productivity and species suitability changes in Europe. Reg Environ Change. 2015;15:1581–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schelhaas M-J, Nabuurs G-J, Schuck A. Natural disturbances in the European forests in the 19th and 20th centuries. Glob Change Biol. 2003;9:1620–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schelhaas MJ, et al. Introducing tree interactions in wind damage simulation. Ecol Model. 2007;207:197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder LM, Lindelöw Å. Attacks on living spruce trees by the bark beetle Ips typographus (Col. Scolytidae) following a storm-felling: a comparison between stands with and without removal of wind-felled trees. Agric For Entomol. 2002;4:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schröter D, et al. Ecosystem service supply and vulnerability to global change in Europe. Science. 2005;310:1333–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1115233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher S, et al. Modeling the impact of climate and vegetation on fire regimes in mountain landscapes. Landscape Ecol. 2006;21:539–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher S, Bugmann H, Mladenoff DJ. Improving the formulation of tree growth and succession in a spatially explicit landscape model. Ecol Model. 2004;180:175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schwilk DW, Ackerly DD. Flammability and serotiny as strategies: correlated evolution in pines. Oikos. 2001;94:326–36. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl R, et al. Evaluating the accuracy and generality of a hybrid patch model. Tree Physiol. 2005;25:939–51. doi: 10.1093/treephys/25.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl R, et al. Increasing forest disturbances in Europe and their impact on carbon storage. Nat Clim Change. 2014;4:806–10. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl R, et al. Modelling tree mortality by bark beetle infestation in Norway spruce forests. Ecol Model. 2007;206:383–99. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl R, et al. Pervasive growth reduction in Norway spruce forests following wind disturbance. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl R, Rammer W. Climate change amplifies the interactions between wind and bark beetle disturbances in forest landscapes. Landscape Ecol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10980-016-0396-4. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl R, Schelhaas M-J, Lexer MJ. Unraveling the drivers of intensifying forest disturbance regimes in Europe. Glob Change Biol. 2011;17:2842–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw TA, et al. Storm track processes and the opposing influences of climate change. Nat Geosci. 2016;9:656–64. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Pedro M, Rammer W, Seidl R. A disturbance-induced increase in tree species diversity facilitates forest productivity. Landscape Ecol. 2016;31:989–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Spiecker H, et al. Growth Trends in European Forests. Berlin: Springer; 1996. p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian N, et al. Adaptation of forest management Regimes in Southern Sweden to increased risks associated with climate change. Forests. 2015;7:8. [Google Scholar]

- Temperli C, et al. Interactions among spruce beetle disturbance, climate change and forest dynamics captured by a forest landscape model. Ecosphere. 2015;6:art231. [Google Scholar]

- Temperli C, Bugmann H, Elkin C. Adaptive management for competing forest goods and services under climate change. Ecol Appl. 2012;22:2065–77. doi: 10.1890/12-0210.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temperli C, Bugmann H, Elkin C. Cross-scale interactions among bark beetles, climate change, and wind disturbances: a landscape modeling approach. Ecol Monogr. 2013;83:383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Thom D, et al. Slow and fast drivers of the natural disturbance regime in Central European forest ecosystems. For Ecol Management. 2013;307:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Thom D, Seidl R. Natural disturbance impacts on ecosystem services and biodiversity in temperate and boreal forests. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2016;91:760–81. doi: 10.1111/brv.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomé M, et al. Eucalyptus in a Changing World. Portugal: RAIZ, Instituto de Investigação da Floresta e do Papel; 2004. Hybridizing a stand level process-based model with growth and yield models for Eucalyptus globulus plantations in Portugal; pp. 290–97. [Google Scholar]

- Urban DL, O’Neill RV, Shugart HHJ. Landscape ecology. A hierarchical perspective can help scientists understand spatial patterns. BioScience. 1987;37:119–27. [Google Scholar]

- Valor T, et al. Influence of tree size, reduced competition, and climate on the growth response of Pinus nigra Arn. salzmannii after fire. Ann For Sci. 2013;70:503–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wamelink GWW, et al. Modelling impacts of changes in carbon dioxide concentration, climate and nitrogen deposition on carbon sequestration by European forests and forest soils. For Ecol Manage. 2009;258:1794–805. [Google Scholar]

- Wermelinger B. Ecology and management of the spruce bark beetle Ips typographus—a review of recent research. For Ecol Manage. 2004;202:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wermelinger B, Seifert M. Temperature-dependent reproduction of the spruce bark beetle Ips typographus, and analysis of the potential population growth. Ecol Entomol. 1999;24:103–10. [Google Scholar]

- Westerling AL, et al. Continued warming could transform Greater Yellowstone fire regimes by mid-21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13165–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110199108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PS, Jentsch A. The Search for Generality in Studies of Disturbance and Ecosystem Dynamics. Berlin: Springer; 2001. pp. 399–450. [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann L, Ravn HP. The spread of Ips typographus (L.) (Coleoptera, Scolytidae) attacks following heavy windthrow in Denmark, analysed using GIS. For Ecol Manage. 2001;148:31–9. [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden P, Mitchell JFB. ENSEMBLES: Climate Change and its Impacts: Summary of research and results from the ENSEMBLES project. 2009. p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann NE. D2.2 Climate and Land Use Data. Deliverable MOTIVE project, Models for Adaptive Forest Management. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zubizarreta-Gerendiain A, Pukkala T, Peltola H. Effects of wood harvesting and utilisation policies on the carbon balance of forestry under changing climate: a finnish case study. Forest Policy Econ. 2016;62:168–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zubizarreta-Gerendiain A, Pukkala T, Peltola H. Effects of wind damage on the optimal management of boreal forests under current and changing climatic conditions. Can J For Res. 2017;47:246–56. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.