Abstract

Nanocarriers are widely used for effective delivery of anticancer drugs to tumours with potential to improve cancer treatment. Here, we developed a nanoceria (CeO2)-based system for delivery of the anti-cancer drug doxorubicin (DOX) to human ovarian cancer cells. Negatively charged nanoceria could conjugate with the cationic DOX via electrostatic interaction under physiological conditions, forming DOX-loaded nanoceria (CeO2/DOX). CeO2/DOX particles displayed nearly spherical shapes, along with superior drug-loading content (22.41%), loading efficiency (99.51%), and higher cellular uptake and drug release behaviours compared to free DOX. Moreover, DOX was released faster from CeO2/DOX under reductive acidic conditions (pH 5.0, 10 mM glutathione) than under physiological conditions (pH 7.4). The initial intracellular DOX concentration was higher in the free DOX groups than in the CeO2/DOX groups, but quickly reduced to 25% of the initial concentration after 24-h culture. By contrast, CeO2/DOX showed sustained DOX release over time and maintained a high intracellular DOX concentration for up to 72 h. In vitro assays showed that CeO2/DOX exhibited higher cell proliferation inhibition and apoptosis compared with free DOX. These results highlight DOX-loaded nanoceria as a promising therapeutic agent for cancer treatment.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the fifth most prevalent cancer among women causing death and is the most lethal gynaecologic malignancy, mainly owing to late-stage diagnosis. If the cancer is detected in its earliest stages, more than 90% of the patients have a better prognosis. In the last few decades, new treatment modalities with improved diagnostic methods and surgical techniques were established, but only a marginal survival improvement was gained1. Most patients will ultimately recur and succumb to their disease. In many cases, chemotherapy helps to improve the overall survival of patients with ovarian cancer2. Many chemotherapeutic drugs are currently used in clinical practice, such as doxorubicin (DOX), cisplatin, decitabine, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, cyclophosphamide, carboplatin, and their combinations, for ovarian cancer treatment3. However, there is an urgent need to identify new therapeutic agents that can improve the efficacy of existing therapeutic modalities.

Nanotechnology is a rapidly growing field towards the development of nanomedical products to improve therapeutic strategies against cancer, and have been shown to improve the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of conventional chemotherapeutic agents and enhance their efficacy with less toxicity4. Nanoceria, or cerium oxide (CeO2), is a rare-earth metal oxide with the unique ability to switch between Ce4+ and Ce3+ depending on the environment5. Karakoti et al.6 reported that nanoceria shows active switching from Ce4+ to Ce3+ in acidic medium, whereas the higher oxidation state is more stabilized in basic medium. Nanoceria possesses excellent antioxidant properties because of its ability to switch between mixed oxidation states7, 8. Walkey et al.9 demonstrated that nanoceria is emerging as an antiinflammatory material. They also reported that the interaction with biological molecules such as proteins, lipids and anions alter the behaviour of nanoceria in vivo. Nanoceria can interact with phosphate ester bonds of biologically relevant molecules, and the dephosphorylation reaction depends on the availibility of Ce(III) sites and is inhibited when Ce(III) is converted to Ce(IV)10. However, nanoceria do not dephosphorylate DNA10, 11. Nanoceria shows a pH-dependent effect on reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation12. It has been reported that nanoceria acts primarily as a scavenger of H2O2 in (neutral) normal tissues but as a producer of H2O2 in an (acidic) cancer environment13. The pro and anti-oxidant properties of nanoceria depent on several other factors, such as, particle shape and size, surface chemistry, and surface additives or ligands that can participate in redox reactions14, 15. However, the toxicity and cellular interaction are largely dependent on the physicochemical properties of nanoceria16. Nanoceria has been shown to produce a sustained regression of oxidative stress-induced neovascularizations, prevent pathologic vascular leakage and inhibit in young adult vldlr(-/) mice17. Besides, the use of nanoceria as a potential drug delivery system has also been reported by several researchers18, 19.

Giri et al.20 showed that nanoceria could act as a therapeutic agent in ovarian cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. Specifically, they showed that nanoceria (containing 63% Ce3+) could inhibit ROS generation and vascular endothelial growth factor-induced proliferation, and could attenuate cell migration and invasion without affecting cell proliferation. Furthermore, the same group21 later showed that folic acid-conjugated nanoceria (FA-CeO2 containing 24% Ce3+) inhibited ovarian cancer cell proliferation (due to increased cellular uptake) and increased ROS production. Despite these differences in its pro- or anti-oxidant nature, both studies demonstrated an association of nanoceria with significant reduction in tumour growth and attenuation of angiogenesis in an ovarian cancer nude mouse model. Moreover, they also showed that the combination of FA-CeO2 with cisplatin decreased the tumour burden significantly, even compared to the cisplatin alone-treated group. Similar kind of anti-invasive effects of nanoceria on human melanoma cells as well as antitumor and antiangiogenic effects in in vivo tumor model were observed22. Sack et al.23 showed a synergistic effect on cytotoxicity and oxidative damage after co-incubation with nanoceria and DOX in human melanoma cells, whereas nanoceria protected human dermal fibroblasts against DOX-induced cytotoxicity. Nanoceria has also been shown to have anticancer activity in several other types of cancers, including in colon, cutaneous squamous, and pancreatic cancer models12, 13, 24, and the increased generation of ROS was believed to be one of the mechanisms contributing to its anti-tumour effect.

DOX is one of the most widely used chemotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of various kinds of cancers, including ovarian cancer3, 25, 26. However, its efficiency is limited owing to the short intracellular retention with lower applicable dosages. The clinical use of DOX is also restricted due to its profound cardiotoxicity, which can cause irreversible cardiomyopathy and/or heart failure27, 28. In the current study, we conjugated DOX with nanoceria to enhance its cytotoxicity, and investigated the potential of CeO2/DOX nanocomplexes in inhibiting ovarian cancer growth in vitro. Herein, we propose that high anticancer efficiency can be achieved by combining the advantages of DOX as a conventional chemotherapeutic drug and the anti-tumorigenic nature of nanoceria to prepare a one-particle system (CeO2/DOX).

Results

Preparation and characterization of CeO2 and CeO2/DOX complexes

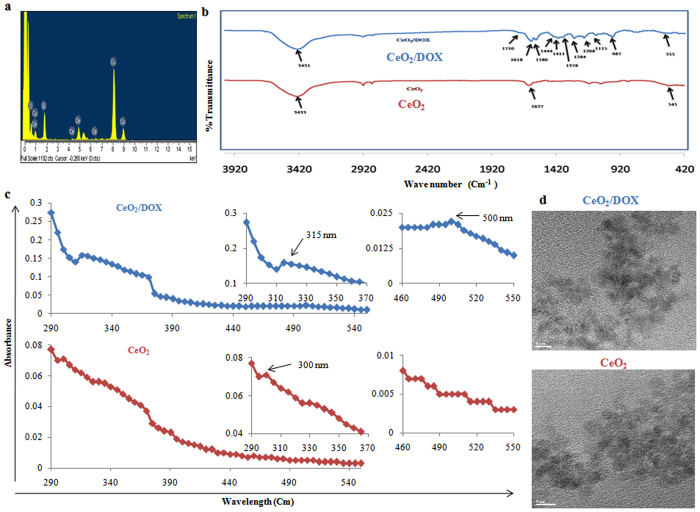

Nanoceria (CeO2) was prepared according to the method described in our previous publication11 by simply refluxing ammonium cerium (IV) nitrate and urea. Characterization of the synthesized CeO2 was achieved by EDS and FTIR spectroscopic analyses. The EDS spectrum depicted characteristic peaks of Ce and O (Fig. 1a). In addition, a Cu peak arising from the TEM grid and an Si peak from the detector were observed. The chemical nature of CeO2 was also verified from the FTIR spectrum, which showed a characteristic absorption band at 500 to 550 cm−1 due to the Ce-O stretching vibration (Fig. 1b). Infrared absorption bands were also observed at 3433 cm−1 and 1627 cm−1 due to water molecules adsorbed on the nanoparticle surface (Fig. 1b). We have also checked the crystal structure (by XRD analysis) of the synthesized CeO2 nanoparticles. Figure S1a shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the synthesized nanoceria. The high intensity peaks were observed at 29.08, 32.98, 47.72, 56.94, 69.84 and 77.78 respective to the (111), (200), (220), (311), (400) and (331) crystal planes. These diffraction peaks indicates a cubic fluorite structure18, 29, 30. The nanoceria were further examined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to determine the different valence states. Figure S1b shows a relatively higher abundance of Ce4+ corresponding to the binding energy peaks at 883, 889, 899, 902, 908, and 917 eV18, 31, 32. The indicative peaks of Ce3+ at 880, 885 and 900 eV are suppressed by high intensity Ce4+ peaks18, 31, 32. However, a clear indicative peak of Ce3+ is present at 905 eV position. Therefore, both the +3 and +4 oxidation states are present in nanoceria, but the major valence of Ce is 4+. McCormack et al.33 reported that nanoceria with higher percentage of surface Ce+3 oxidation states are more prone to interact with phosphate ions and forming cerium phosphate, thereby influencing the catalytic activities of nanoceria. As we have seen that our synthesized nanoceria showed higher abundance of Ce4+ oxidation states (confirmed by XPS data), we expect less interaction with phosphate ions. Therefore, we can practically ignore the effects of phosphate ions on the physiological functions of nanoceria and used PBS to suspend CeO2 and CeO2/DOX nanocomplex.

Figure 1.

Characterization of CeO2 and CeO2/DOX nanoparticles. (a) EDS spectrum of CeO2; (b) FTIR spectrum of CeO2 and CeO2/DOX; (c) UV-VIS spectra of CeO2 and CeO2/DOX; (d) TEM images of CeO2 and CeO2/DOX.

After confirming the synthesis of CeO2, DOX was loaded onto CeO2 via electrostatic interactions. The amount of DOX bound to the nanoceria surface was determined by UV absorption measurements at 480 nm. The DLE and DLC contents were 99.51% and 22.41%, respectively (Table 1). The adsorption of DOX on the CeO2 surface was also confirmed by FTIR analysis. The FTIR spectrum of DOX-loaded CeO2 showed multiple characteristic peaks of DOX (Fig. 1b). The broad peak at 3431 cm−1 can be assigned to the stretching band of -OH groups. The peak at 1710 cm−1 is due to the stretching band of C=O groups; peaks at 1618 cm−1 and 1580 cm−1 are due to the bending band of N-H groups; the peak at 1411 cm−1 is due to C-C stretching; the peak appearing at 1284 cm−1 is due to framework vibration of the carbonyl group in DOX’s anthracene cycle; the peak at 1208 cm−1 is due to C-O-C asymmetric stretching vibration; and the peak at 987 cm−1 is due to C-O stretching of the alcohol group34–37. These results indicate that DOX was successfully loaded onto the CeO2 nanoparticles.

Table 1.

Drug loading content (DLC) and drug loading efficiency (DLE) of CeO2/DOX nanoparticles.

| Feed ratio, CeO2: DOX (w/w) | DLC % | DLE % |

|---|---|---|

| 5: 1.45 | 22.41 | 99.51 |

The optical properties of synthesized CeO2 were checked by acquisition of the UV spectrum, which showed a distinct absorption peak at 300 nm and was devoid of impurity peaks (Fig. 1c). However, in the case of CeO2/DOX, the absorption peak appeared at 315 nm (Fig. 1c), which indicated a larger particle size. The CeO2/DOX complex also showed a characteristic peak of loaded DOX at 500 nm (Fig. 1c), which was absent in the spectrum of CeO2 nanoparticles. TEM analysis showed that the synthesized CeO2 particles were almost spherical, with diameters in the range of 3–4 nm (Fig. 1d). However, the apparent increase in the size of the CeO2/DOX complexes was not clear from the TEM images.

The processes of DOX deposition on the CeO2 surface and complex formation between CeO2 and DOX were also monitored by DLS and zeta-potential analyses. The DLS data suggested that the average diameter of CeO2 and CeO2/DOX particles was 208 ± 9 nm and 308 ± 5 nm, respectively (Fig. S2). The size of the CeO2 particles increased by approximately 100 nm when loaded with DOX. The size of nanoparticles appear bigger by DLS compared to by TEM analysis due to extensive solvation/hydration of nanoparticles. The results can be explained by the fact that by DLS measurement, the average diameter is calculated from the diffusional properties of dynamic nanoparticles in hydrated state. On the other hand, by TEM analysis, the average primary particle diameter is calculated in static and dried state38, 39. The polydispersity index of the synthesized CeO2 and CeO2/DOX complexes was below 0.3, indicating a uniform and homogeneous size distribution. The zeta potential of CeO2 was −27 ± 1.6 mV in PBS (pH 7.4), which increased to −16 ± 0.6 mV after DOX loading due to the association with positively charged DOX (Fig. S2).

In vitro DOX release from CeO2/DOX complexes

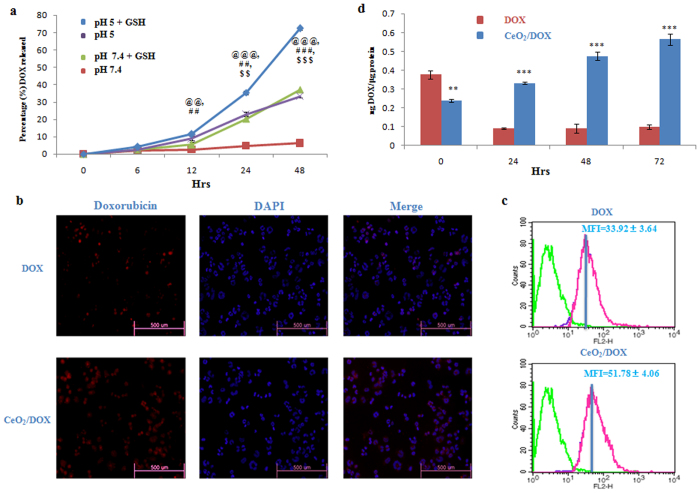

The time-dependent in vitro release of DOX from CeO2/DOX complexes was investigated under physiological conditions (PBS, pH 7.4) and in a mildly acidic environment (pH 5.0) simulating the endo-lysosomal pH, as well as in combination with GSH (10 mM) that is present in high concentrations within lysosomes. In neutral PBS (pH 7.4), only a very small amount of DOX was released from CeO2/DOX in a very slow fashion, and the cumulative release of DOX was only about 6.23% within 48 h (Fig. 2a). In PBS of pH 5.0, the release rate of DOX from CeO2/DOX became much faster. The cumulative release of DOX from CeO2/DOX could reach as high as about 33.37% within 48 h, which was approximately 5.4-times higher than that observed at pH 7.4 (Fig. 2a). This result demonstrated that the release of DOX from CeO2/DOX nanoparticles was pH-sensitive. However, we have also checked the release profile of DOX from CeO2/DOX nanoparticles in medium mimicking the in vivo environment, such as PBS (pH = 7.4) containing 10% serum and observer that the cumulative release of DOX was only about 6% within 48 h (Fig. S1c).

Figure 2.

Intracellular uptake of CeO2/DOX nanoparticles and release of DOX from CeO2/DOX nanoparticles. (a) DOX release profiles of the CeO2/DOX nanoparticles in PBS under different conditions at 37 °C. The GSH concentration was fixed at 10 mM. The equivalent DOX concentration was 5 μg/mL. @p < 0.05, @@p < 0.01 and @@@p < 0.01 versus the pH 7.4 group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.01 versus the pH 7.4,GSH group, $p < 0.05, $$p < 0.01 and $$$p < 0.01 versus the pH 5 group. (b,c) Cellular uptake of free DOX and CeO2/DOX nanoparticles after incubation of A2780 cells with a 2 μg/mL equivalent DOX concentration for 3 h, measured by fluorescence microscopy and FACS; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (d) Quantitative evaluation of intracellular DOX released from CeO2/DOX. A2780 cells were first treated with a 2 μg/mL equivalent DOX concentration for 3 h (taken as the 0 time-point), washed, and left untreated for a further 24, 48, and 72 h in DOX-free medium. All values are expressed as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and **p < 0.001 versus the free DOX-treated group.

It is noteworthy that the GSH addition to the release medium had a significant influence on the release rates of DOX from the nanocomplexes. The percentage of released DOX (72.35%) within the first 48 h under reductive conditions (pH 5.0, GSH 10 mM) was much higher than that (33.37%) observed at pH 5.0 (Fig. 2a). However, only 35.45% and 22.78% of the DOX was released within the first 24 h under the reductive condition (pH 5.0, GSH 10 mM) and at pH 5.0, respectively, indicating that the drug–nanoparticle interaction is very strong, so that DOX is released in a slow manner (Fig. 2a).

Intracellular uptake of CeO2/DOX nanoparticles

The endocytosis of free DOX and DOX-loaded nanoparticles was compared in A2780 human ovarian cancer cells by both fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry analysis. Since DOX itself is fluorescent, no additional markers were used. The fluorescence intensity is proportional to the amount of DOX internalized by the cells. Fluorescence microscopic images are shown in Fig. 2b. For both free DOX and CeO2/DOX nanoparticles, cellular uptake was observed after 3 h of incubation. DOX accumulation in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus was higher for CeO2/DOX than for free DOX.

The mechanism of cellular uptake of CeO2/DOX complexes into A2780 cells was investigated by pre-treating the cells with several endocytosis inhibitors prior to treatment with CeO2/DOX. The cellular uptake of the CeO2/DOX complexes was then qualitatively assessed by fluorescence microscopic analysis. Cells were pre-treated with several endocytosis inhibitors, including 5 μg/mL CPZ (inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis), 1 mM MBCD (suppressor or inhibitor of caveolae-mediated endocytosis), and 65 μM LY294002 (inhibitor of macropinocytosis). Pre-treatment with CPZ did not influence the fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with CeO2/DOX (Fig. S3). In contrast, pre-treatment with MBCD and LY294002 reduced the fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with CeO2/DOX compared to that of non-treated cells (Fig. S3). This result demonstrated that the CeO2/DOX complexes were selectively taken up by A2780 cells through both caveolin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis.

The cellular uptake of free DOX and CeO2/DOX was further quantitatively checked by flow cytometry analysis. The mean fluorescence intensity was taken to quantitatively compare the endocytosis of DOX between groups. CeO2/DOX showed a 1.5-fold higher fluorescence intensity than free DOX (Fig. 2c). Collectively, these results indicate that CeO2/DOX shows higher cellular uptake via an endocytosis process than free DOX.

Intracellular DOX release and retention

According to the in vitro DOX release profile of CeO2/DOX nanoparticles (Fig. 2a), it could be expected that CeO2/DOX would also show a time-dependent drug release pattern within the cells. A2780 cells were first treated with a 2 μg/mL equivalent DOX concentration for 3 h (taken as the 0 time-point), and the medium was changed. The intracellular DOX concentration was measured at 24-, 48-, and 72-h intervals. The intracellular DOX concentration was higher for the free DOX (0.38 ng/μg protein) treatment groups than in the CeO2/DOX (0.24 ng/μg protein) treatment groups after 3 h of treatment (at the 0 time-point). However, in the free DOX treatment groups, the intracellular DOX concentration quickly decayed (0.09 ng/μg protein) to 25% of the original concentration at the 24-h mark, and stayed at a similar level until 72 h (Fig. 2d). By contrast, the CeO2/DOX groups showed sustained release of DOX over time and maintained a high intracellular DOX concentration up to 72 h (Fig. 2d).

Anti-tumour activity and apoptosis of CeO2 and CeO2/DOX

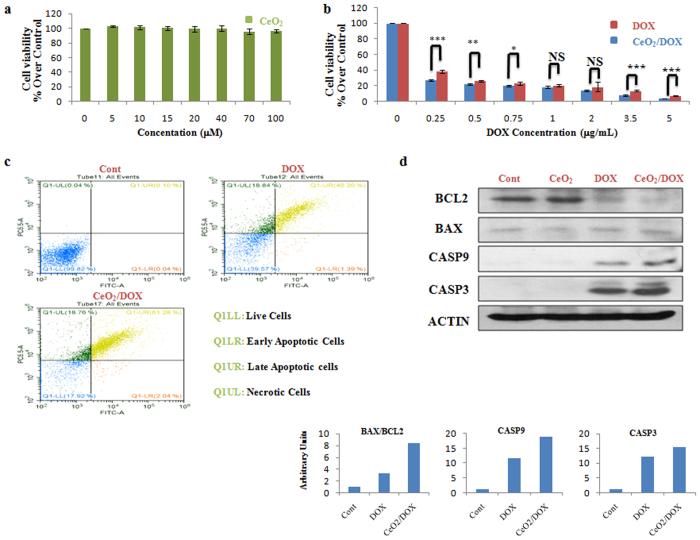

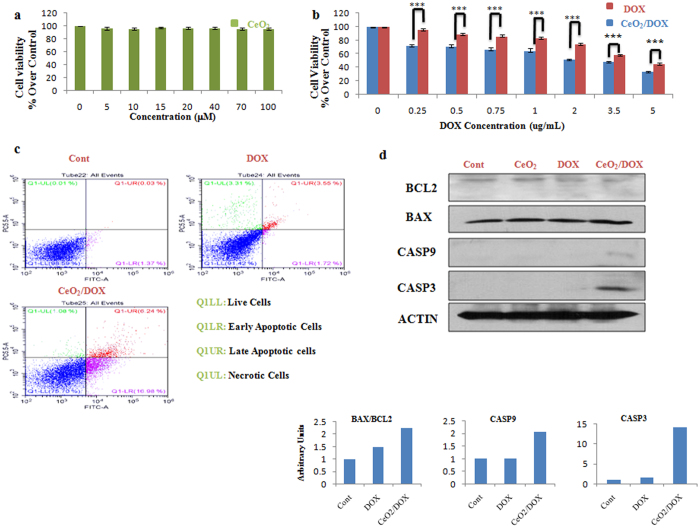

The in vitro cytotoxicity of CeO2 nanoparticles was evaluated using a WST-8 assay. Three different human ovarian cancer cell lines, A2780, SKOV-3, and CAOV-3, were used for this assay. As shown in Fig. 3a, the viability of the A2780 cells treated with CeO2 was 96–100% at all test concentrations from 5 to 100 μM, revealing no significant effect on cell proliferation or survival. The in vitro anti-tumour activity of DOX-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles was also evaluated in the A2780, SKOV-3, and CAOV-3 cells. The cells were incubated with various concentrations of DOX for 3 h and then the medium was replaced with drug-free medium and culture continued for a further 72 h. The cell viabilities were evaluated thereafter and compared between the free-DOX and CeO2/DOX treatment groups. As shown in Fig. 3b, CeO2/DOX exhibited dose-dependent cell proliferation inhibition for A2780 cells. The results also showed that CeO2/DOX appeared to induce a higher anti-tumour effect compared with free DOX for all test concentrations (Fig. 3b). The difference in free DOX- and CeO2/DOX-induced cell death was further supported by AO/EB double-staining analysis at a test concentration of 0.25 μg/mL. AO can enter both live and apoptotic cells where it emits green fluorescence, whereas EB can only enter apoptotic cells where it emits red fluorescence40. The AO/EB assay showed that the percentage of apoptotic cells significantly increased following free DOX or CeO2/DOX exposure (Fig. S4a). The quantitative apoptotic activities of free DOX and CeO2/DOX on A2780 cells were further evaluated by flow cytometry. Cells have been double stained for viability (negative for PI) and apoptosis (positive for Annexin V-FITC). Free DOX and CeO2/DOX resulted in 41.6 and 63.32% apoptotic cells respectively, whereas the necrotic cell population did not differ (19%) among the groups (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

In vitro cytotoxicity of CeO2/DOX in A2780 ovarian cancer cells. (a,b) Cell viability relative to the control (100%). Cells were treated with different concentrations of CeO2, free DOX, or CeO2/DOX for 3 h. The cells were then washed and further cultured in fresh media for 72 h in the absence of any DOX and nanoparticles. All values are expressed as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 versus the free DOX-treated group. (c) Apoptosis (dot plot distribution and % apoptosis calculations) measured by Annexin V/PI assay after exposure to 0.25 μg/mL equivalent doxorubicin for 3 h followed by washing and cultured for further 72 h in DOX free media. (d) Western blot analysis of apoptotic proteins. Cells were treated with a 0.25 μg/mL equivalent DOX concentration (either free DOX or CeO2/DOX) or with 5 μM CeO2 for 3 h, washed, and further cultured for 72 h. Densitometric analysis was carried out using Image J software.

To explore the possible signalling pathways through which DOX-loaded nanoparticles induced greater anticancer activity, we further evaluated the changes in the expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins by western blot analysis at the lowest test concentration applied (0.25 μg/mL). We observed that the expression of the apoptosis-regulating protein BCL-2 was down-regulated in both the free-DOX and CeO2/DOX groups, whereas BAX expression was not substantially altered when compared with that of the control group (Fig. 3d). However, the ratio of BAX to BCL-2 protein expression was more obviously increased in the CeO2/DOX group (8.33-fold) than in the free-DOX group (3.18-fold). As shown in Fig. 3d, the expression of cleaved caspase-9 was up-regulated in both the free-DOX and CeO2/DOX groups compared with the control group (Fig. 3d), and the increase was much more dramatic in the CeO2/DOX group (18.83-fold) than in the free-DOX group (11.68-fold). A similar result was detected for cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 3d). Notably, the protein expression level in the CeO2-only group did not obviously differ compared with that of the control group (Fig. 3d).

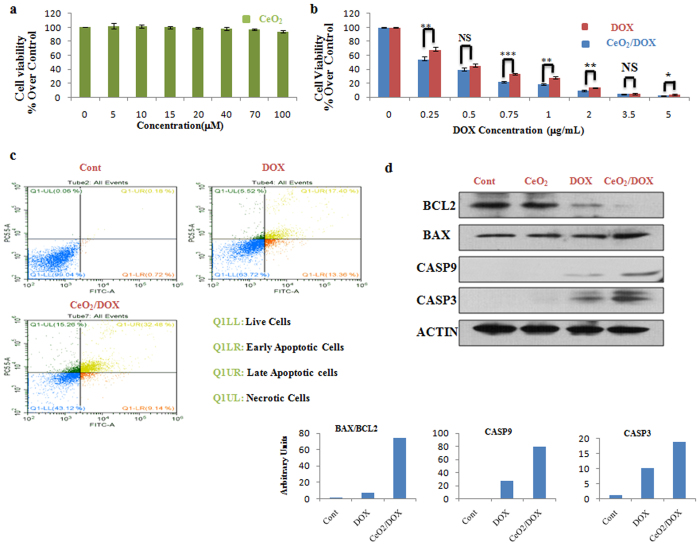

Similar to A2780 cells, CeO2 also showed no significant effect on cell proliferation or survival in CAOV3 cells (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b shows that CeO2/DOX exhibited dose-dependent cell proliferation inhibition for CAOV3 cells, and appeared to induce a higher in vitro anti-tumour effect compared with free DOX at all test concentrations. The occurrence of apoptosis was also supported by AO/EB dual staining and AnnexinV/PI assay following free DOX or CeO2/DOX exposure at 0.25 μg/mL test concentration (Figs 4c, S4b). Free DOX and CeO2/DOX resulted in 30.8 and 41.6% apoptotic cells and 5.5 and 15.3% necrotic cells respectively (Fig. 4c). Immunoblotting analysis (Fig. 4d) further revealed that CeO2/DOX significantly increased the ratio of BAX to BCL-2 protein expression (74.4-fold), cleaved caspase-9 (80-fold), and caspase-3 (18.66-fold) compared with those of the free DOX group (6.4-fold, 28-fold, and 10.1-fold, respectively) at the lowest applied concentration (0.25 μg/mL).

Figure 4.

In vitro cytotoxicity of CeO2/DOX in CAOV3 ovarian cancer cells. (a,b) Cell viability relative to the control (100%). Cells were treated with different concentrations of CeO2, free DOX, or CeO2/DOX for 3 h. The cells were then washed and further cultured in fresh media for 72 h in the absence of any DOX and nanoparticles. All values are expressed as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 versus the free DOX-treated group. (c) Apoptosis (dot plot distribution and % apoptosis calculations) measured by Annexin V/PI assay after exposure to 0.25 μg/mL equivalent doxorubicin for 3 h followed by washing and cultured for further 72 h in DOX free media. (d) Western blot analysis of apoptotic proteins. Cells were treated with a 0.25 μg/mL equivalent DOX concentration (either free DOX or CeO2/DOX) or with 5 μM CeO2 for 3 h, washed, and further cultured for 72 h. Densitometric analysis was carried out using Image J software.

Finally, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of the CeO2 nanoparticles in SKOV3 cells and compared the in vitro anti-tumour effect between free DOX and CeO2/DOX nanoparticles. CeO2 did not induce any significant cell proliferation inhibition (Fig. 5a), and CeO2/DOX exhibited a higher in vitro anti-tumour effect than free DOX within the concentration range of 0.25–5 μg/mL (Fig. 5b). However, at the concentration of 0.25 μg/mL, free DOX did not induce significant apoptotic cell death as evident from AO/EB dual staining, AnnexinV/PI assay and immunoblotting analysis (Figs 5c,d, S4c). On the other hand, CeO2/DOX induced extensive apoptosis as evident from AO/EB dual staining, AnnexinV/PI assay and increased expression of cleaved Caspase-9 (2 fold) and Caspase-3 (14.29 fold) (Figs 5c,d, S4c). Similar to the cell viability assay, the tendency towards increased apoptotic activity of CeO2/DOX in all tested human ovarian cancer cell lines is probably due to its ability for higher cellular uptake through endocytosis and sustained DOX release.

Figure 5.

In vitro cytotoxicity of CeO2/DOX in SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells. (a,b) Cell viability relative to the control (100%). Cells were treated with different concentrations of CeO2, free DOX, or CeO2/DOX for 3 h. The cells were then washed and further cultured in fresh media for 72 h in the absence of any DOX and nanoparticles. All values are expressed as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 versus the free DOX-treated group. (c) Apoptosis (dot plot distribution and % apoptosis calculations) measured by Annexin V/PI assay after exposure to 0.25 μg/mL equivalent doxorubicin for 3 h followed by washing and cultured for further 72 h in DOX free media. (d) Western blot analysis of apoptotic proteins. Cells were treated with a 0.25 μg/mL equivalent DOX concentration (either free DOX or CeO2/DOX) or with 5 μM CeO2 for 3 h, washed, and further cultured for 72 h. Densitometric analysis was carried out using Image J software.

Discussion

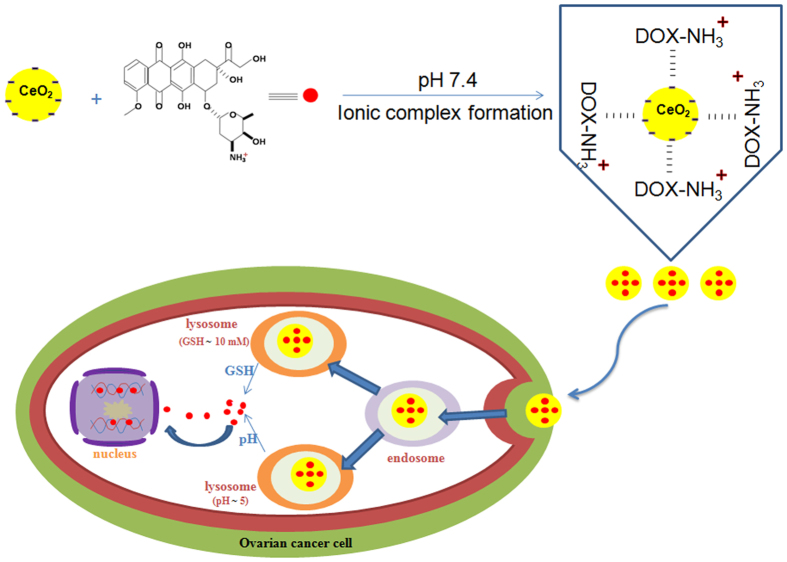

In the present study, we have developed a new nanoceria (CeO2)-based drug delivery system wherein a model cationic anticancer drug, DOX, was loaded onto negatively charged CeO2 nanoparticles via simple electrostatic interaction for in vitro drug delivery applications to human ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of CeO2/DOX nanoparticle preparation, uptake in ovarian cancer cells and release of DOX.

Nanoceria (CeO2) was prepared by simply refluxing ammonium cerium (IV) nitrate and urea as described in our previous publication11. After confirming the synthesis of CeO2 by EDS and FTIR spectroscopic analyses, DOX was loaded onto CeO2 via electrostatic interactions. The adsorption of DOX on the CeO2 surface was confirmed by multiple characteristic peaks of DOX obtained from the FTIR spectrum of DOX-loaded CeO2. The DLE and DLC contents were 99.51% and 23.37%, respectively. The processes of DOX deposition on the CeO2 surface and complex formation between CeO2 and DOX were also monitored by UV-VIS spectroscopy and zeta-potential analyses. The CeO2/DOX complex displayed a characteristic peak of loaded DOX at 500 nm. The zeta potential of CeO2 was increased by approximately 11 mV when loaded with DOX due to the association with positively charged DOX.

This synthesized CeO2/DOX could maintain strong drug–nanoparticle electrostatic interactions under physiological conditions, and exhibited pH/reduction dual-responsive drug release behaviour. However, CeO2/DOX nanoparticles are also stable in medium mimicking the in vivo environment, such as PBS (pH = 7.4) containing 10% serum. Therefore, we can conclude that the CeO2/DOX system is stable in in vivo microenvironment and have the potential to be used as in vivo drug delivery vehicle. CeO2 is known to show a pH-dependent surface charge41, 42. At low pH, it shows a positive surface charge (zeta potential) due to the adsorption of H+ ions on its surface, whereas at higher pH, it shows a negative surface charge due to the adsorption of OH− ions on its surface. Given that the positively charged DOX was loaded onto the negatively charged CeO2 nanoparticles at physiological pH, the electrostatic interaction between CeO2 and DOX was weakened in a low pH environment, and hydrophilic DOX was therefore released from the nanoparticle surface.

The GSH-triggered DOX release can be explained by the GSH-induced reduction of Ce4+ to Ce3+ and formation of a stable disulphide bridge/Ce(III) complex43, leading to DOX release from the nanoparticle surface. Therefore, the highly pH/reduction-responsive release behaviours could be ascribed to the weak electrostatic interaction between CeO2 and DOX in a low pH environment, as well as the enhanced drug diffusion caused by stable Ce3+/GSSG complex formation. This pH/reduction dual responsiveness is a very useful biological stimulus exploited for triggered drug release, because pH values and intracellular GSH concentrations vary among different cellular organelles. For example, the pH in the endosomes and lysosomes is lower (<5.5) than that in the blood (pH 7.4). By contrast, the intracellular GSH concentration is low in the bloodstream, but is very high inside lysosomes. Therefore, this pH/reduction dual-sensitive drug carrier would not only reduce the amount of drug loss to the blood circulation but would also undergo drug release during the endocytosis process, thereby improving the overall therapeutic efficacy.

The fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry analyses showed that the CeO2/DOX nanoparticles had a higher level of cancer cell uptake compared with free DOX. However, the DOX fluorescence of CeO2/DOX might be derived from both the free DOX and the nanoparticle-bound DOX. Free DOX and DOX-conjugated nanoparticles show different cellular uptake mechanisms44. Free DOX is known to be transported into cells via a passive diffusion mechanism and can quickly diffuse through the cell membrane, whereas DOX-conjugated nanoparticles are taken up via the endocytosis pathway. In the case of CeO2/DOX, DOX fluorescence was observed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, indicating that the CeO2/DOX complexes were initially located within the intracellular compartments (endosomes and lysosomes), and were then released into the cytosol to ultimately enter the nucleus. We further investigated the cellular uptake pathways of CeO2/DOX nanoparticles by pre-treating cells with selective endocytosis inhibitors, and found that the nanocomplexes were internalized through caveolin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis.

We have also checked the intracellular DOX release from the CeO2/DOX nanoparticles in A2780 cells. Although the intracellular DOX concentration was higher for the free DOX treatment groups after 3 h of treatment, but quickly decayed to 25% of the original concentration at the 24-h mark. Yu et al.45 also demonstrated a similar pattern of DOX decay (catabolism) in MBT-2 bladder cancer cells within 24 h. By contrast, the CeO2/DOX groups showed sustained release of DOX over time and maintained a high intracellular DOX concentration up to 72 h. This result is consistent with the in vitro DOX release profile of CeO2/DOX. Although the cellular uptake of CeO2/DOX was higher than that of the free DOX treatment groups (Fig. 2a,b), the released free DOX concentration was lower (Fig. 2d) after the first 3 h of incubation. However, we found that CeO2/DOX showed 6-, 8-, and 9-fold higher DOX retention rates compared with the free DOX treatment groups at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, respectively, which could be attributed to the efficient cellular uptake and prolonged drug release behaviour of the complex over time.

Epithelial ovarian cancer which is the cause of most ovarian cancer-related deaths consists of five distinct subtypes of ovarian carcinomas, namely high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC), clear cell carcinoma (CCC), endometrioid carcinoma (EC), mucinous carcinoma (MC) and low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC)46. High-grade serous carcinoma is the most common type of ovarian carcinomas. Almost half of ovarian CCC and EC are present at stage I and diagnosed. On the other hand, LGSC and MC is the least common among the major types of ovarian carcinomas. Therefore, we have used three different human ovarian cancer cell lines, A2780 (EC model)47, SKOV-3 (COC model)48, and CAOV-3 (HGSC model)49 to check the in vitro anti-tumor activity of CeO2/DOX nanoparticles. The in vitro cytotoxicity and cell apoptosis experiments confirmed that CeO2/DOX exhibited higher tumour cell growth inhibition over free DOX in all of the tested human ovarian cancer cells. This confirmed that the released drug was active. CeO2 did not induce any significant cell proliferation inhibition or apoptosis, which is consistent with previous studies20, 21 using non-targeted nanoceria. However, folic acid-conjugated nanoceria (FA-CeO2) could inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells because of increased cellular internalization20, 21. Hijaz et al.21 also showed that FA-CeO2 was more effective in inhibiting tumour growth than CeO2 alone in a xenograft mouse model. Moreover, they also showed that the combination of FA-CeO2 with cisplatin decreased the tumour burden significantly, even compared to the cisplatin alone-treated group. Therefore, specific targeting of nanoceria and combination with standard chemotherapy holds great potential as an effective therapeutic strategy in ovarian cancer. However, we can expect a better result of the combination therapy in a synergistic or combined mannar in in vivo model, because of the antiangiogenic effects of nanoceria10, 11, 22. The in vivo tumor micro-environment is different from in vitro cell culture system and tumor-associated blood vessel formation has been implicated as a key part in the process of growth, invasion, and metastasis of malignancies50. Because of the antioxidative property of nanoceria towards normal cells, this CeO2/DOX system may offer a novel strategy in cancer treatment by lowering the side effects of doxorubicin, thereby improving the therapeutic outcome23. Besides, the CeO2/DOX system is stable in in vivo microenvironment. Therefore, DOX-loaded nanoceria has the potential to be used as in vivo drug delivery vehicle and can be considered as a promising therapeutic agent for cancer treatment.

Methods

Materials

Ammonium cerium (IV) nitrate, urea, doxorubicin hydrochloride, and foetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Penicillin-streptomycin solution, trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), RPMI, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution were obtained from Life Technologies GIBCO (Grand Island, NY, USA). The bicinchoninic acid protein assay system was obtained from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA). Antibodies against caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), BCL-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), cleaved caspase 9, BAX, and beta-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) were used for immunoblotting.

Preparation of nanoceria (CeO2) and the nanoceria-doxorubicin complex (CeO2/DOX)

The protocol for nanoceria (CeO2) preparation is described in detail in our previous report17. A stock solution of nanoceria was prepared by dissolving an appropriate amount of nanoceria in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), followed by sonication; the solution was kept at room temperature. The synthesized nanoceria was characterized by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS; Oxford EDS-6636), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer Spectroscopy GX, PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), XRD (HRXRD, Brucker D8 Discover) and XPS (Sigma Probe).

For the preparation of CeO2/DOX complexes, a DOX solution was prepared by dissolving an appropriate amount of DOX in PBS (pH 7.4), which was then combined with the nanoceria suspension (pH 7.4) and the mixture was stirred overnight in the dark. The mixture solution was subsequently centrifuged at 14,000 g for 10 min to remove the excess DOX, and the red-coloured slurry was washed three times with water. The slurry was resuspended in PBS and kept at 4 °C. The synthesized CeO2/DOX complexes were characterized by FTIR spectroscopy (Perkin Elmer Spectroscopy GX). The drug-loading efficiency (DLE) and drug-loading content (DLC) were determined by ultraviolet (UV) absorption at 480 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), UV spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering (DLS), and zeta-potential measurements

The primary sizes of CeO2 and CeO2/DOX complexes were measured by TEM, using a JEM-1200EX microscope at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV. The UV-visible spectra of CeO2 and the CeO2/DOX complexes were acquired using an Optizen POP (Mecasys, South Korea) instrument. The hydrodynamic sizes and zeta potentials of CeO2 and the CeO2/DOX complexes were measured in water using a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments, Ltd., Malvern, UK) instrument.

Cell culture

Human ovarian cancer cells (A2780, SKOV3) were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin. CAOV3 human ovarian cancer cells were cultured in DMEM. The cells were cultured in a humidified incubator maintained at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2.

In vitro DOX release from CeO2/DOX complexes

The in vitro release profiles of DOX from CeO2/DOX were investigated in neutral and acidic PBS solutions (pH 7.4 and 5.0) with and without glutathionine (GSH, 10 mM), using a dialysis diffusion technique. For the drug release evaluation, an appropriate amount of CeO2/DOX (equivalent DOX concentration of 5 μg/mL) was resuspended in 10 mL PBS, sealed in dialysis bags (MWCO 3500 Da), and incubated in PBS (40 mL) at 37 °C with shaking at 100 rpm. At a predetermined time, 4 mL of the incubated solution was taken out and replaced with fresh PBS. The released amount of DOX was determined by measuring the emission fluorescence intensity at 590 nm with an excitation wavelength of 490 nm, using a Gemini EM microplate reader (SpectraMAX, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Cellular uptake of CeO2/DOX complexes

The cellular uptake experiments were performed using fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. For microscopic analysis, A2780 cells were seeded onto glass coverslips placed in six-well plates at 1 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were then treated with free DOX or CeO2/DOX (DOX concentration = 2 μg/mL) for 3 h. The cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed with fresh 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. The cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Coverslips were placed onto glass microscope slides, and DOX uptake was visualized using a fluorescence microscope. To evaluate the cellular uptake pathways, the cells were pre-treated with several endocytosis inhibitors such as 1 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MBCD) or 5 μg/mL chlorpromazine (CPZ), or with a macropinocytosis inhibitor (65 μM LY294002; Sigma–Aldrich) for 30 min. The cells were then treated with the CeO2/DOX complexes, as described above, in the presence of the added inhibitors, and DOX uptake was visualized using a fluorescence microscope.

The DOX uptake was also quantified by flow cytometry using a FACS Calibur system, and the data were analysed with Cell Quest software.

Intracellular DOX release and retention

A2780 cells were exposed to either free DOX or CeO2/DOX at an equivalent DOX concentration of 2 μg/mL for 3 h (taken as the 0 time-point). The cells were then washed three times with PBS and further cultured in DOX-free media for 72 h. At various time points, the cells were washed and then lysed for 10 min in lysis buffer and centrifuged at 4000 rpm. The supernatants were collected, and the fluorescence of the released DOX was measured using the Gemini EM microplate reader at 490-nm excitation and 590-nm emission wavelengths.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells were seeded (1.5 × 104 cells/well) into 96-well, flat-bottom culture plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were then treated with different concentrations of CeO2 (5–100 μM), DOX (0.25–5 μg/mL), or CeO2/DOX (equivalent DOX concentration of 0.25–5 μg/mL) for 3 h in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium containing 10% FBS, and the cells were further cultured without DOX and nanoparticles for 72 h. A cell viability assay was performed using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan), and the absorbance was read at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microtitre plate reader (Multiskan FC, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) staining

DOX-induced apoptosis was detected by AO/EB double staining. Cells were seeded in 24-well plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were then treated with either free DOX (0.25 μg/mL) or CeO2/DOX (equivalent DOX concentration of 0.25 μg/mL) for 3 h at 37 °C. The cells were washed with PBS and further cultured for 72 h with fresh medium containing 10% FBS without DOX. Finally, the cells were washed with PBS and stained with the AO/EB mixture (100 μg/mL) for 5 min, followed by another three washes with PBS. The cells were visualised using an inverted fluorescence microscope under an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm for AO staining, and an excitation wavelength of 520 nm and emission wavelength of 590 nm for EB staining.

Assessment of apoptotic cell populations

Cells were seeded (1.5 × 104 cells/well) into 96-well, flat-bottom culture plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were then treated with DOX (0.25 μg/mL), or CeO2/DOX (equivalent DOX concentration of 0.25 μg/mL) for 3 h in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium containing 10% FBS, and the cells were further cultured without DOX and nanoparticles for 72 h. Cell death was analyzed using FITC conjugated Annexin V and propidium iodide with an Apoptosis detection kit (Komabioteh, Seoul, South Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were characterized using cytoFLEX flow cytometer.

Immunoblotting

The cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Equal amounts of protein were resolved by 12–13% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the proteins were electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked at room temperature with 6% non-fat dry milk for 2 h to prevent non-specific binding, and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Immunoreactivity was detected through sequential incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate, and statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Student t-tests. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Joydeep Das is a recipient of a fellowship from the Konkuk University Brain Pool Program. This work was supported by the Science Research Center (2015R1A5A1009701) from the National Research Foundation of Korea and Biogreen 21 (PJ011328).

Author Contributions

J.D. and J.H.K. designed the study; J.D. performed the research; J.H.K. supervised the study; J.W.H and J.D. characterized the nanoparticles; J.D., J.H.K., Y.J.C., and A.M.M.T.R analyzed the data; J.D. and J.H.K wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09876-w

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coward JI, Middleton K, Murphy F. New perspectives on targeted therapy in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Womens Health. 2015;7:189–203. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S52379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong DK. Relapsed ovarian cancer: challenges and management strategies for a chronic disease. Oncologist. 2002;7:20–28. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-suppl_5-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yallapu MM, Jaggi M, Chauhan SC. Scope of nanotechnology in ovarian cancer therapeutics. J. Ovarian Res. 2010;3 doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wicki A, Witzigmann D, Balasubramanian V, Huwyler J. Nanomedicine in cancer therapy: challenges, opportunities, and clinical applications. J. Control Release. 2015;200C:138–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estevez AY, Erlichman JS. The potential of cerium oxide nanoparticles (nanoceria) for neurodegenerative disease therapy. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:1437–1440. doi: 10.2217/nnm.14.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karakoti AS, Kuchibhatla SVNT, Babu KS, Seal S. Direct Synthesis of Nanoceria in Aqueous Polyhydroxyl Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:17232–17240. doi: 10.1021/jp076164k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochella MF, Jr, et al. Nanominerals, mineral nanoparticles, and earth systems. Science. 2008;319:1631–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1141134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu JC, Zhang L, Lin J. Direct sonochemical preparation of high-surface-area nanoporous ceria and ceria-zirconia solid solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;260:240–243. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9797(02)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walkey C, et al. Catalytic Properties and Biomedical Applications of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2015;2:33–53. doi: 10.1039/C4EN00138A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuchma MH, et al. Phosphate ester hydrolysis of biologically relevant molecules by cerium oxide nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das J, et al. Cationic lipid-nanoceria hybrids, a novel nonviral vector-mediated gene delivery into mammalian cells: investigation of the cellular uptake mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep29197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alili L, et al. Combined cytotoxic and anti-invasive properties of redox-active nanoparticles in tumor-stroma interactions. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2918–2929. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wason MS, et al. Sensitization of pancreatic cancer cells to radiation by cerium oxide nanoparticle-induced ROS production. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:558–569. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grulke E, et al. Nanoceria: factors affecting its pro- and anti-oxidant properties. Environ. Sci.: Nano. 2014;1:429–444. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar A, et al. Behavior of nanoceria in biologically-relevant environments. Environ. Sci.: Nano. 2014;1:516–532. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dowding JM, et al. Cellular interaction and toxicity depend on physicochemical properties and surface modification of redox-active nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2013;7:4855–4868. doi: 10.1021/nn305872d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai X, Seal S, McGinnis JF. Sustained inhibition of neovascularization in vldlr-/- mice following intravitreal injection of cerium oxide nanoparticles and the role of the ASK1-P38/JNK-NF-κB pathway. Biomaterials. 2014;35:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muhammad F, Wang A, Qi W, Zhang S, Zhu G. Intracellular Antioxidants Dissolve Man-Made Antioxidant Nanoparticles: Using Redox Vulnerability of Nanoceria to Develop a Responsive Drug Delivery System. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:19424–19433. doi: 10.1021/am5055367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patil S, Reshetnikov S, Haldar MK, Seal S, Sanku M. Surface-Derivatized Nanoceria with Human Carbonic Anhydrase II Inhibitors and Fluorophores: A Potential Drug Delivery Device. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2007;111:8437–8442. doi: 10.1021/jp067666l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giri S, et al. Nanoceria: a rare-earth nanoparticle as a novel anti-angiogenic therapeutic agent in ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hijaz M, et al. Folic acid tagged nanoceria as a novel therapeutic agent in ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16 doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alili L, et al. Downregulation of tumor growth and invasion by redox-active nanoparticles. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013;19:765–778. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sack M, et al. Combination of conventional chemotherapeutics with redox-active cerium oxide nanoparticles–a novel aspect in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1740–1749. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jana SK, Banerjee P, Das S, Seal S, Chaudhury K. Redox-active nanoceria depolarize mitochondrial membrane of human colon cancer cells. J. Nanopart. Res. 2014;16 doi: 10.1007/s11051-014-2441-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singal PK, Iliskovic N. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:900–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809243391307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buzdar AU, Marcus C, Smith TL, Blumenschein GR. Early and delayed clinical cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin. Cancer. 1985;55:2761–2765. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850615)55:12<2761::AID-CNCR2820551206>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orhan B. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: growing importance. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999;17:2294–2296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2293c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silber JH, Barber G. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1359–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chelliah M, Rayappan JBB, Krishnan UM. Synthesis and characterization of cerium oxide nanoparticles by hydroxide mediated approach. J. Applied Sci. 2012;12(1734–17) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng H, Lin S, Muhammad F, Lin YW, Wei H. Rationally Modulate the Oxidase-like Activity of Nanoceria for Self-Regulated Bioassays. ACS Sens. 2016;1:1336–1343. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.6b00500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirst SM, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Small. 2009;5:2848–2856. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy BM, Thrimurthulu G, Katta L, Yamada Y, Park SE. Structural Characteristics and Catalytic Activity of Nanocrystalline Ceria-Praseodymia Solid Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:15882–15890. doi: 10.1021/jp903644y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCormack RN, et al. Inhibition of Nanoceria’s Catalytic Activity due to Ce3+ Site-Specific Interaction with Phosphate Ions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:18992–19006. doi: 10.1021/jp500791j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L, et al. A redox stimuli-responsive superparamagnetic nanogel with chemically anchored DOX for enhanced anticancer efficacy and low systemic adverse effects. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:8949–8962. doi: 10.1039/C5TB01851J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unsoy G, Khodadust R, Yalcin S, Mutlu P, Gunduz U. Synthesis of doxorubicin loaded magnetic chitosan nanoparticles for pH responsive targeted drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014;62:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding W, Guo L. Immobilized transferrin Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticle with high doxorubicin loading for dual-targeted tumor drug delivery. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2013;8:4631–4639. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S51745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chouhan R, Bajpai A. Real time in vitro studies of doxorubicin release from PHEMA nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2009;7 doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SK, Han MS, Asokan S, Tung CH. Effective Gene Silencing by Multilayered siRNA-Coated Gold Nanoparticles. Small. 2011;7:364–370. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pecora R. Dynamic Light Scattering Measurement of Nanometer Particles in Liquids. J Nanopart Res. 2000;2:123–131. doi: 10.1023/A:1010067107182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasibhatla S, et al. Acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) staining to detect apoptosis. Cold Spring Harbor Protoc. 2006;3(10) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu B, Sun Z, Huang PJ, Liu J. Hydrogen peroxide displacing DNA from nanoceria: mechanism and detection of glucose in serum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:1290–1295. doi: 10.1021/ja511444e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Chen G, Guay D, Chaker M, Ma D. Highly active PtAu alloy nanoparticle catalysts for the reduction of 4-nitrophenol. Nanoscale. 2014;6:2125–2130. doi: 10.1039/C3NR04715F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rollin-Genetet F, et al. Redox reactivity of cerium oxide nanoparticles induces the formation of disulfide bridges in thiol-containing biomolecules. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015;28:2304–2312. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prabaharan M, Grailer JJ, Pilla S, Steeber DA, Gong S. Amphiphilic multi-armblock copolymer conjugated with doxorubicin via pH-sensitive hydrazone bond for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5757–5766. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu DS, Yan HY, Wu CL, Hung SH. Comparison of therapeutic efficacy of lipo-doxorubicin and doxorubicin in treating bladder cancer. Urolog. Sci. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anglesio MS, et al. Type-specific cell line models for type-specific ovarian cancer research. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Armstrong SR, et al. Distinct genetic alterations occur in ovarian tumor cells selected for combined resistance to carboplatin and docetaxel. J. Ovarian Res. 2012;5 doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-5-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaw TJ, Senterman MK, Dawson K, Crane CA, Vanderhyden BC. Characterization of intraperitoneal, orthotopic, and metastatic xenograft models of human ovarian cancer. Mol. Ther. 2004;10:1032–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitra, A. K. et al. In vivo tumor growth of high-grade serous ovarian cancer cell lines. Gynecol. Oncol. 138372–377 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Saphir, A. Angiogenesis: the unifying concept in cancer? J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 89, 1658–1659 (1997). [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.