Abstract

Background

Racial disparities in preterm birth and infant mortality have been well documented. Less is known about racial disparities in neonatal morbidities among infants born prior to 37 weeks.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine if risk for morbidity and mortality among infants born preterm differs by maternal race.

Study Design

A retrospective cohort design included medical records from preterm deliveries of 19,325 Black, Hispanic, and White women in the Consortium on Safe Labor. Sequentially-adjusted Poisson models with generalized estimating equations estimated racial differences in risk for neonatal morbidities and mortality controlling for maternal demographics, health behaviors, and medical history. Sex differences between and within race were examined.

Results

Black preterm infants had an elevated risk for perinatal death, but there was no difference in risk for neonatal death across racial groups. Relative to Whites, Black infants were significantly more likely to experience sepsis (9.1% vs. 13.6%), peri- or intraventricular hemorrhage (2.6% vs. 3.3%), intracranial hemorrhage (0.6% vs. 1.8%), and retinopathy of prematurity (1.0% vs. 2.6%). Hispanic and White preterm neonates had similar risk profiles. In general, female infants had lower risk relative to males, with White females having the lowest prevalence of a composite indicator perinatal death or any morbidity across all races (30.9%). Differences in maternal demographics, health behaviors, and medical history did little to influence these associations, which were robust to sensitivity analyses of pregnancy complications as potential underlying mechanisms.

Conclusions

Preterm infants were at similar risk for neonatal death regardless of race, but there were notable racial disparities and sex differences in rare, but serious adverse neonatal morbidities.

Keywords: preterm birth, transient tachypnea, respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage, retinopathy of prematurity, neonatal mortality, perinatal mortality

Introduction

Black and Hispanic women in the U.S. are more likely to deliver preterm (<37 weeks) compared with White women, and a higher proportion of Black women experience fetal or perinatal losses and infant mortality compared with other races.1,2 The persistent racial disparity in infant mortality may be driven in part by the greater incidence of extremely preterm births – those occurring before the limit of viability – among Black women,3 essentially all of which result in neonatal death. Among viable preterm births however, Blacks have historically experienced lower risks of neonatal mortality relative to Whites,4,5 but more recent data suggest the survival advantage among Black early preterm infants diminished during the 1990s, and the racial disparity in mortality after 33 weeks gestation has increased.6

Reasons behind these entrenched disparities remain largely unexplained, but are thought to be driven by complex and multifaceted risk exposure arising from generations of social and economic disadvantage that place women and their neonates at risk for morbidity and mortality.7 While disparities in mortality and preterm birth have been well documented, less is known about racial differences in morbidity among preterm neonates – particularly for rare conditions – which may shape the trajectory of infant health and survival. Sparse evidence suggests trends similar to mortality with risk by racial group inverse between preterm and term neonates. In an analysis based on gestational-age matched birth records from the state of Ohio, Loftin et al.8 reported that compared to Whites, Blacks had lower risk of morbidity during the preterm period (through 36 weeks), but the risk increased after 37 weeks. Berman et al.9 found that among neonates born <34 weeks, Whites were more than twice as likely as Blacks to have a Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology greater than 10, indicating greater physiologic severity for neonatal intensive care.9

Few previous studies have identified sex differences in neonatal morbidities among very preterm births (<29 weeks), but to date none of the cohorts were among the U.S. population.10,11 An analysis of data from 797 infants born at 23–28 weeks’ gestation in the United Kingdom found that female infants were at a significantly lower risk for death and oxygen dependency, pulmonary hemorrhage and other major cranial abnormalities.10 An Australian cohort of 2,549 very preterm neonates identified increased risk for adverse long-term neurologic outcomes among males compared to females and sex differences were most pronounced among births before 27 weeks of gestation.11 Neither study examined the joint effects of sex and race on preterm neonatal health.

The purpose of this analysis was to describe racial/ethnic differences in neonatal morbidities among neonates born preterm, and to investigate whether racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal morbidity differed by infant sex in a large, U.S. medical record-based cohort. Further, we aimed to explore how differences in maternal demographic characteristics, health behaviors, and medical history explain racial differences in preterm neonatal morbidities.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Data were obtained from the Consortium on Safe Labor, a retrospective cohort of 228,438 deliveries from 12 U.S. clinical centers between 2002 and 2008 in the following states: California, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Utah.12 Detailed information was obtained from electronic medical records after Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at all participating institutions. International Classification of Diseases, version 9 (ICD-9) maternal discharge diagnosis codes were recorded for each pregnancy, which included pregnancy complications and medical history. Maternal records were linked to newborn electronic medical records, which included details of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions, as well as ICD-9 discharge codes for the infants. Women’s self-reported race and ethnicity was recorded in the medical record and compiled in the central CSL database in the following categorizations: Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Asian/Pacific Islander, multi-racial, other race, or unknown. Given limited sample sizes, we included only Hispanic, White, or Black women in this analysis and excluded women of all other race/ethnicities (n=24,214), multiple births (n=4,609), infants with congenital anomalies (n=13,717) and births missing maternal age (n=132).

(n=24,214), multiple births (n=4,609), infants with congenital anomalies (n=13,717) and births missing maternal age (n=132). We further limited the analysis to deliveries that occurred <37 weeks gestation for a final sample of 19,857 singletons among 19,325 women (n=6,720, 34.8% Black; n=3,799, 19.7% Hispanic; and n=8,806, 45.6% White).

Outcome and Covariates

Neonatal outcomes of interest were identified by ICD-9 codes and included: asphyxia, NICU admission, transient tachypnea (TTN), respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), peri-/intraventricular hemorrhage (PVH/IVH), intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), neonatal mortality and perinatal mortality (defined as stillbirth or neonatal death). We also examined a composite outcome that included neonates who experienced at least one of the above outcomes – perinatal death and/or any morbidity – compared to those who were live born without morbidities. Analyses of all outcomes – with the exception of perinatal mortality and the composite outcome– excluded stillbirths (n=648).

A priori selected covariates included study site, maternal age (continuous), parity (nulliparous, multiparous), pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI, kg/m2: underweight, <18.5; normal weight 18.5–24.9; overweight, 25 –29.9; obese, ≥30; unknown), insurance type (private; public/self-pay; other/unknown), marital status (married; not married or unknown), smoking during pregnancy (yes; no/unknown), alcohol use during pregnancy (yes; no/unknown), mode of delivery (vaginal, Cesarean-section), maternal history of asthma, depression, hypertension, renal disease, heart disease, diabetes, or thyroid disease (separate covariates, yes; no/unknown).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics compared covariates between racial/ethnic groups using chi-square and ANOVA for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. We fit a series of sequentially-adjusted Poisson regression models with generalized estimating equations to estimate racial/ethnic differences in risk for adverse neonatal outcomes using Whites as the reference group and to account for multiple observations contributed by some women. Model A adjusted only for study site. Model B further adjusted for maternal demographics including age, age-squared, parity, insurance, smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, and marital status. Model C further included history of chronic diseases, mode of delivery and pre-pregnancy BMI. Prepregnancy BMI was missing in 7,107(35.8%) of deliveries due to a lack of height and/or weight measure recorded in the medical record. Therefore, we used multiple imputation in order to derive estimates of pre-pregnancy BMI and retain all observations for modeling. The multiple imputation was based on observed values of pre-pregnancy weight, parity, insurance status, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, age, race, and study site.

A six-category variable grouped infants by race/ethnicity and sex in order to compare relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each neonatal outcome controlling for all covariates in the fully-adjusted Model C above. The reference group of White females was selected based on the sex/race group with the highest proportion of infants experiencing a live birth with the lowest burden of morbidity. We tested for interactions between race/ethnicity and infant sex as well as maternal race/ethnicity and age given documented racial differences in age-patterned risk for adverse birth outcomes.13

Finally, in a sensitivity analysis we examined the robustness of racial/ethnic differences in the composite outcome (death or at least 1 morbidity) after controlling for a range of complications that may have arisen during pregnancy differentially by maternal race/ethnicity and associated with neonatal outcomes: preeclampsia, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), chorioamnionitis, gestational hypertension, and gestational diabetes. These were included in a model containing all the covariates in fully-adjusted Model C.

Results

In the cohort, White women were older, and more likely to be married and have private insurance compared with other racial/ethnic groups (Table 1). Smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy was more frequent among Whites compared to Blacks or Hispanics. Rates of asthma, hypertension, and obesity were highest among Black women while White women had a higher rate of depression and thyroid disease.

Table 1.

Medical and demographic characteristics of preterm births by maternal race, N=19,857.

| White n=9,024 |

Black n=6,950 |

Hispanic n=3,883 |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

|

|

||||

| Maternal Age | 28.3 (6.2) n(%) |

26.3 (6.7) n(%) |

27.3 (6.8) n(%) |

<0.001 |

|

|

||||

| Parity | <0.001 | |||

| Nulliparous | 3,811 (42.2) | 2,437 (35.1) | 1,444 (37.2) | |

| Multiparous | 5,213 (57.8) | 4,513 (64.9) | 2,439 (62.8) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 6,289 (69.7) | 1,554 (22.4) | 1,798 (46.3) | |

| Not married/unknown | 2,735 (30.3) | 5,396 (77.6) | 2,085 (53.7) | |

| Insurance type | <0.001 | |||

| Private | 6,029 (66.8) | 2,187 (31.5) | 1,125 (29.0) | |

| Public/self-pay | 2,514 (27.9) | 4,006 (57.6) | 2012 (51.8) | |

| Other/unknown | 481 (5.3) | 757 (10.9) | 746 (19.2) | |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 1,121 (12.4) | 724 (10.4) | 224 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 283 (3.1) | 173 (2.5) | 52 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 439 (4.9) | 207 (3.0) | 119 (3.1) | |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 3,174 (35.2) | 1,627 (23.4) | 1,295 (33.4) | |

| Overweight (25 – 29.9 kg/m2) | 1,244(13.8) | 1,005 (14.5) | 689 (17.7) | |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 1,180 (13.1) | 1,187 (17.1) | 584 (15.0) | |

| Chronic medical conditions | ||||

| Asthma | 889 (9.5) | 837 (12.1) | 283 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 783 (8.7) | 261 (3.8) | 167 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 225 (2.5) | 412 (5.9) | 121 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 124 (1.4) | 117 (1.7) | 65 (1.7) | 0.22 |

| Heart disease | 209 (2.3) | 171 (2.5) | 79 (2.0) | 0.36 |

| Diabetes | 256 (2.8) | 323 (4.7) | 183 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Thyroid disease | 300 (3.3) | 73 (1.1) | 65 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy Complications | ||||

| Preeclampsia (mild+severe) | 1,213 (13.4) | 952 (13.7) | 488 (12.6) | 0.24 |

| Preeclampsia (mild+severe+superimposed) | 1,447 (16.0) | 1,385 (19.9) | 660 (17.0) | 0.24 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 316 (3.5) | 514 (7.4) | 271 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes | 1,839 (20.4) | 1,301 (18.7) | 707 (18.2) | <0.01 |

| Gestational hypertension | 342 (3.8) | 197 (2.9) | 88 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes | 591 (6.6) | 420 (6.0) | 346 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| Mode of Delivery | <0.05 | |||

| Vaginal | 5,751 (63.7) | 4,345 (62.5) | 2,380 (61.3) | |

| Cesarean section | 3,273 (36.3) | 2,605 (37.5) | 1,503 (38.7) | |

| Infant sex | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 4,765 (53.1) | 3,388 (49.4) | 2,040 (52.7) | |

| Female | 4,202 ( 46.9) | 3,466 (50.6) | 1,829 (47.3) | |

| Neonatal Outcomes | ||||

| Respiratory Distress Syndrome | 1736 (19.2) | 1182 (17.0) | 613 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 820 (9.1) | 948 (13.6) | 450 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| Periventricular/intraventricular hemorrhage | 231 (2.6) | 232 (3.3) | 126 (3.2) | 0.01 |

| Transient tachypnea | 936 (10.4) | 838 (12.1) | 364 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| Asphyxia | 63 (0.7) | 63 (0.9) | 33 (0.9) | 0.32 |

| Neonatal death | 93 (1.0) | 153 (2.2) | 62 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Perinatal mortality | 313 (3.5) | 405 (5.8) | 194 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Perinatal Death or any morbidity | 3,115 (34.5) | 2,59 (37.3) | 1,270 (32.7) | <0.001 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 86 (1.0) | 64 (0.9) | 44 (1.1) | 0.54 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 56 (0.6) | 128 (1.8) | 61 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 90 (1.0) | 182 (2.6) | 94 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 4,107 (45.5) | 3,235 (46.6) | 1,613 (41.5) | <0.001 |

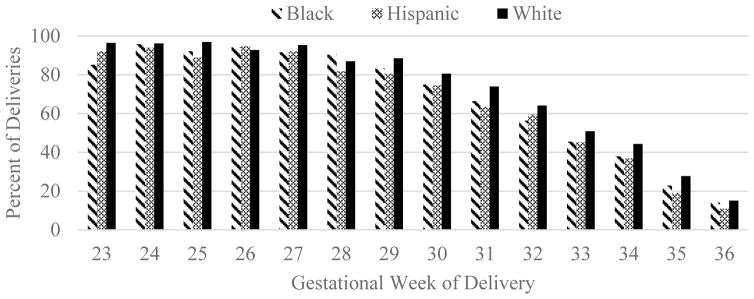

Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of infants experiencing perinatal death or at least one of the morbidities of interest by race/ethnicity and gestational week (for morbidity-specific figures, see Supplemental Figure 1S). Empirical rates of death or morbidity varied among White, Black, and Hispanic neonates until 29 weeks and onward when White neonates the highest, followed by Black then Hispanic (with the exception of 32 weeks when the Hispanic rate was higher than Black).

Figure 1.

Percent of Deliveries with Perinatal Death or Neonatal Morbidity by Maternal Race

Associations between maternal race/ethnicity and neonatal outcomes are shown in Table 2. Overall, adjustment for covariates across Models A-C did not appreciably change the magnitude of associations between race and risk for each outcome. Across all three models, Black neonates were at 41–43% increased risk for sepsis, 31–33% increased risk for PVH/IVH, 52–67% increased risk for ICH, and 41–60% increased risk for ROP and 45–48% increased risk for perinatal death compared with Whites. Hispanics were at 11–12% decreased risk for RDS, and 13–16% increased risk for sepsis. Site-only adjusted Model A indicated a lower risk for transient tachypnea among Hispanics compared with Whites (RR=0.87, 95% CI=0.77, 0.99), and a 5% decrease risk for NICU admission, but the differences were not statistically significant in subsequent models. There were no racial/ethnic differences in a combined perinatal death or any morbidity in the final fully-adjusted Model C.

Table 2.

Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for associations between maternal race and neonatal outcomes among preterm births, n= 19,857.

| Model Aa | Model Bb | Model Cc | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | ||||

| Respiratory distress syndrome | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 0.99 | 0.91 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.10 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 1.07 |

| Hispanic | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.96 |

| Sepsis | |||||||||

| White | Ref | -- | |||||||

| Black | 1.41 | 1.27 | 1.57 | 1.43 | 1.29 | 1.61 | 1.42 | 1.26 | 1.58 |

| Hispanic | 1.13 | 1.00 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.01 | 1.30 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 1.30 |

| PVH/IVH | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 1.32 | 1.04 | 1.69 | 1.33 | 1.02 | 1.72 | 1.31 | 0.97 | 1.66 |

| Hispanic | 0.99 | 0.76 | 1.28 | 1.01 | 0.77 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.28 |

| Transient tachypnea | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.11 | 1.01 | 0.90 | 1.12 |

| Hispanic | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 1.01 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.01 |

| Asphyxia | |||||||||

| White | Ref | -- | |||||||

| Black | 1.40 | 0.92 | 2.12 | 1.48 | 0.96 | 2.28 | 1.41 | 0.80 | 2.02 |

| Hispanic | 1.11 | 0.70 | 1.75 | 1.08 | 0.68 | 1.72 | 1.07 | 0.58 | 1.56 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 1.28 | 0.82 | 1.98 | 1.13 | 0.70 | 1.81 | 1.13 | 0.60 | 1.66 |

| Hispanic | 1.11 | 0.72 | 1.70 | 1.01 | 0.64 | 1.59 | 1.03 | 0.56 | 1.49 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 1.52 | 1.11 | 2.11 | 1.67 | 1.18 | 2.37 | 1.60 | 1.02 | 2.17 |

| Hispanic | 1.36 | 0.94 | 1.97 | 1.31 | 0.87 | 1.98 | 1.28 | 0.75 | 1.82 |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 1.41 | 1.06 | 1.89 | 1.60 | 1.17 | 2.18 | 1.56 | 1.08 | 2.04 |

| Hispanic | 1.18 | 0.85 | 1.63 | 1.24 | 0.88 | 1.75 | 1.26 | 0.83 | 1.69 |

| NICU admission | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.08 |

| Hispanic | 0.95 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.00 |

| Neonatal death | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 1.32 | 0.94 | 1.86 | 1.37 | 0.96 | 1.95 | 1.33 | 0.85 | 1.81 |

| Hispanic | 0.97 | 0.65 | 1.45 | 1.05 | 0.69 | 1.58 | 1.05 | 0.61 | 1.48 |

| Perinatal deathd | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 1.46 | 1.23 | 1.74 | 1.48 | 1.22 | 1.78 | 1.45 | 1.17 | 1.72 |

| Hispanic | 1.15 | 0.94 | 1.41 | 1.17 | 0.95 | 1.44 | 1.15 | 0.91 | 1.40 |

| Perinatal death or any morbidity | |||||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Black | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 0.99 | 1.10 |

| Hispanic | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.98 |

Model A is adjusted for study site

Model B is adjusted for study site, maternal age, squared maternal age, parity, insurance type, smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, and marital status.

Model C is adjusted for all covariates in Model B as well as mode of delivery, maternal history of chronic diseases (asthma, depression, hypertension, renal disease, heart disease, diabetes, and thyroid disease), pre-pregnancy BMI, and mode of delivery.

Perinatal death includes stillbirths (n=648) which were excluded from all other outcomes

There was evidence of an interaction between infant sex and race but not between maternal age and race/ethnicity in these data. Stratification by both race/ethnicity and sex revealed more nuanced trends (Table 3). Risk of perinatal mortality was highest among Blacks overall, and was not specific to infant sex; both Black females and males had 50% and 69% increase in risk, respectively, compared with White females. Likewise, Hispanics were at lower risk for RDS overall and there was no difference in risk between males or females compared to white females. Conversely, while there were no racial/ethnic differences in RDS risk, sex differences emerged with males of either White or Black race at increased risk relative to White or Black females (Black males RR=1.18, 95% CI=1.05, 1.31;White males RR=1.27, 95% CI=1.16, 1.37; Black females RR=1.07, 95% CI=0.95, 1.19). Similarly, TTN risk was not differential by race/ethnicity but by sex with both Black and White males at 18% increased risk compared to White females and no difference between Black, White, and Hispanic females. The combined influence of both sex and race/ethnicity was apparent for NICU admission and the composite outcome of death or any morbidity. There were no racial/ethnic differences in these outcomes overall; however, after further stratification, White males as well as Black neonates of either sex were 10–14% more likely to be admitted to the NICU than White females and 11–21% more likely to experience perinatal death or at least one morbidity, with a stronger association in males of either race.

Table 3.

Adjusted relative risks and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sex and race of neonate and neonatal outcomes among preterm births.a

| % of deliveries within race and sex | RR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory distress syndrome | ||||

| White females | 17.4 | Ref | ||

| White males | 21.9 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.37 |

| Black females | 16.9 | 1.07 | 0.95 | 1.19 |

| Black males | 18.7 | 1.18 | 1.05 | 1.31 |

| Hispanic females | 15.5 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 1.08 |

| Hispanic males | 17.0 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 1.17 |

| Sepsis | ||||

| White females | 8.3 | Ref | ||

| White males | 10.2 | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.38 |

| Black females | 13.8 | 1.54 | 1.31 | 1.77 |

| Black males | 14.7 | 1.64 | 1.40 | 1.88 |

| Hispanic females | 11.6 | 1.26 | 1.04 | 1.48 |

| Hispanic males | 12.3 | 1.32 | 1.10 | 1.54 |

| PVH/IVH | ||||

| White females | 2.4 | Ref | ||

| White males | 2.8 | 1.15 | 0.85 | 1.44 |

| Black females | 3.6 | 1.46 | 0.98 | 1.93 |

| Black males | 3.4 | 1.35 | 0.91 | 1.79 |

| Hispanic females | 3.0 | 0.95 | 0.59 | 1.30 |

| Hispanic males | 3.6 | 1.17 | 0.77 | 1.56 |

| Transient tachypnea | ||||

| White females | 9.8 | Ref | ||

| White males | 11.4 | 1.18 | 1.04 | 1.32 |

| Black females | 11.7 | 1.03 | 0.88 | 1.18 |

| Black males | 13.5 | 1.18 | 1.01 | 1.34 |

| Hispanic females | 8.3 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.99 |

| Hispanic males | 11.0 | 1.13 | 0.94 | 1.31 |

| Asphyxia | ||||

| White females | 0.6 | Ref | ||

| White males | 0.8 | 1.43 | 0.71 | 2.16 |

| Black females | 0.8 | 1.42 | 0.56 | 2.28 |

| Black males | 1.1 | 2.01 | 0.89 | 3.14 |

| Hispanic females | 0.6 | 0.95 | 0.27 | 1.63 |

| Hispanic males | 1.1 | 1.60 | 0.65 | 2.55 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | ||||

| White females | 0.9 | Ref | ||

| White males | 1.1 | 1.17 | 0.68 | 1.67 |

| Black females | 0.9 | 1.10 | 0.44 | 1.75 |

| Black males | 1.1 | 1.34 | 0.56 | 2.11 |

| Hispanic females | 1.0 | 0.92 | 0.34 | 1.50 |

| Hispanic males | 1.3 | 1.22 | 0.51 | 1.93 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | ||||

| White females | 0.8 | Ref | ||

| White males | 0.5 | 0.76 | 0.36 | 1.15 |

| Black females | 1.8 | 1.28 | 0.69 | 1.88 |

| Black males | 2.1 | 1.48 | 0.81 | 2.15 |

| Hispanic females | 1.5 | 1.00 | 0.45 | 1.56 |

| Hispanic males | 1.8 | 1.21 | 0.58 | 1.84 |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | ||||

| White females | 1.2 | Ref | ||

| White males | 0.9 | 0.79 | 0.47 | 1.12 |

| Black females | 2.9 | 1.46 | 0.91 | 2.00 |

| Black males | 2.6 | 1.33 | 0.81 | 1.85 |

| Hispanic females | 2.4 | 1.10 | 0.62 | 1.57 |

| Hispanic males | 2.5 | 1.15 | 0.65 | 1.65 |

| NICU admission | ||||

| White females | 43.5 | Ref | ||

| White males | 49.2 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.19 |

| Black females | 47.8 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.16 |

| Black males | 48.7 | 1.12 | 1.06 | 1.18 |

| Hispanic females | 41.9 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.06 |

| Hispanic males | 44.0 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.12 |

| Neonatal death | ||||

| White females | 0.7 | Ref | ||

| White males | 0.9 | 1.29 | 0.69 | 1.89 |

| Black females | 1.6 | 1.35 | 0.67 | 2.03 |

| Black males | 2.2 | 1.83 | 0.95 | 2.71 |

| Hispanic females | 1.7 | 1.30 | 0.57 | 2.02 |

| Hispanic males | 1.6 | 1.22 | 0.54 | 1.89 |

| Perinatal mortality | ||||

| White females | 2.8 | Ref | ||

| White males | 3.1 | 1.10 | 0.84 | 1.36 |

| Black females | 4.6 | 1.50 | 1.09 | 1.92 |

| Black males | 5.2 | 1.69 | 1.23 | 2.15 |

| Hispanic females | 5.4 | 1.40 | 0.99 | 1.80 |

| Hispanic males | 4.2 | 1.11 | 0.77 | 1.44 |

| Perinatal death or any morbidity | ||||

| White females | 30.9 | Ref | ||

| White males | 37.1 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 1.28 |

| Black females | 35.1 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.19 |

| Black males | 38.4 | 1.21 | 1.12 | 1.29 |

| Hispanic females | 31.0 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.06 |

| Hispanic males | 33.8 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.15 |

Models were adjusted for study site, maternal age, parity, insurance type, smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, marital status, maternal history of chronic diseases (asthma, depression, hypertension, renal disease, heart disease, diabetes, and thyroid disease), pre-pregnancy BMI, and mode of delivery.

Complications occurring during pregnancy did not explain sex and racial/ethnic differences in risk of mortality or any neonatal morbidity (composite). In the sensitivity model adjusted for preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis, PPROM, gestational hypertension, and gestational diabetes, both White and Black males experienced 21% elevated risk compared to White females, while Black females were at 11% increased risk (data not shown).

Comment

In this analysis of a large medical record-based cohort of 19,857 preterm births from 12 U.S. states, we find evidence of racial/ethnic differences in risk for neonatal morbidity that are not explained by maternal demographic characteristics, health behaviors, or medical history. Previous reports have documented a small but narrowing gestational-age survival advantage among Black neonates relative to Whites for infants born prior to 37 weeks.5,8 In this sample there was no racial/ethnic difference in risk for neonatal death among all infants born preterm, and an increased likelihood of perinatal death among Blacks relative to Whites and Hispanics. Moreover, we found that Black neonates experienced increased risk for multiple morbidities including sepsis, PVH/IVH, ICH, and ROP. Hispanic preterm neonates fared similarly to White neonates in general and had lower rates of RDS. These findings add to the limited evidence of racial/ethnic differences in particularly rare outcomes among neonates born preterm.

The differences in neonatal outcomes for Black neonates persisted after stratification by sex and are largely consistent with the small amount of literature on these rare outcomes. Both incidence and mortality from sepsis have been shown to be higher among Black preterm neonates.14 A previous study found that Black infants were more than twice as likely to die from IVH compared with Whites, attributable in part to the excess risk of preterm birth among Blacks.15 In an analysis limited to preterm deliveries similar to the current study, increased incidence of IVH among Blacks was attenuated among women with at least one prenatal visit, implicating racially-differential health care access and utilization.16 An older study examined the causes and factors of developing PVH/IVH in premature infants and reported that mothers with pregnancy-induced hypertension were less likely to have neonates with PVH/IVH, likely attributable to medication use or obstetrical management.17 Gestational hypertension most commonly complicated pregnancies among White women in our data and risk for IVH was lower in this group. Finally, the elevated risk for ROP among Blacks evident in this study is novel as previous literature has focused largely on an elevated risk among Hispanics18, or a reduced risk for severe ROP among Blacks.19 The factors that have been demonstrated to be associated with an increased risk of ROP are short gestational period or low birth weight, sepsis, intraventricular hemorrhage and blood transfusions. Both Blacks and Hispanics were at an increased risk of sepsis and Blacks were at an increased risk of PVH/IVH within the study population, which is in concordance with the observation that infants who experience those particular morbidities are likely to experience comorbid ROP.18

Risk for RDS and TTN was lowest among Hispanics. Although White preterm neonates are at an increased risk for RDS than other racial/ethnic groups,20 Black infants often do not respond to surfactant treatment as well as others, and RDS-related mortality among Blacks and Hispanics exceeds rates among Whites.21,22 TTN is diagnosed by the presence of labored and rapid breathing in a newborn due to underdeveloped lung function. Newborns are at a higher risk for TTN when they are delivered by C-section, born to mothers with diabetes or asthma, have a small-for-gestational age birthweight, or have any other respiratory distress. 23 Controlling for these factors across Models A-C attenuated racial/ethnic differences in TTN.

We found no racial/ethnic differences in risk for asphyxia, NEC, NICU admission, neonatal death, or the composite variable for death or at least one morbidity. When considering the joint effects of sex and race, in general, females had a reduced risk compared with males. Male sex and Black race have previously been associated with an increased prevalence of birth asphyxia,24 and while asphyxia was rare in our population which may have influenced statistical power, the point estimate was similarly elevated among Black boys relative to White girls. NEC is a severe medical condition primarily seen in premature infants, where portions of the bowel undergo necrosis or tissue death.25 There was limited evidence of significant racial/ethnic differences from other studies, with the exception of one that found that Black preterm infants had an increased risk of NEC compared with other racial/ethnic groups.25 The direction and magnitude of the effect estimates associated with Black and Hispanic risk for NEC in the current study suggest increased risk, and as a rare occurrence, models may have been underpowered to detect a significant difference.

There are several limitations that should be mentioned. Grouping the Hispanic population ignores the heterogeneity of this group, which may include both native and non-native born participants. The small number of Asian/Pacific Islander women and those of other racial/ethnic groups prohibited examining risk for rare outcomes in these groups. Finally, while the medical-records based nature of these data are an improvement over birth records data with regard to outcome validity and accuracy, they lack data on women’s socioeconomic conditions and contextual factors that may explain apparent racial/ethnic differences, such as maternal education, income, access to and utilization of timely, high-quality prenatal care. Future studies on the mechanisms underlying racial/ethnic differences in preterm neonatal morbidities should be encouraged.

The distressing trend in increasing racial/ethnic inequities in maternal and child health outcomes should be of concern to clinicians and public health professionals. Our results challenge findings of a survival advantage among Black preterm neonates in cohorts from previous decades. In fact, we find Black neonates at greater risk for a number of severe morbidities and an almost 50% increased risk of perinatal death when born at less than 37 weeks. Efforts to understand and address the complex and multifaceted mechanisms underlying preterm labor and preterm morbidity are needed to eliminate racial/ethnic differences in risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding source: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The Consortium on Safe Labor was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the NICHD, through Contract No. HHSN267200603425C. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Role of the funding source: The funding source had no direct role in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; or in the writing of the report.

Institutions involved in the Consortium include, in alphabetical order: Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Burnes Allen Research Center, Los Angeles, CA; Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE; Georgetown University Hospital, MedStar Health, Washington, DC; Indiana University Clarian Health, Indianapolis, IN; Intermountain Healthcare and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY; MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.; Summa Health System, Akron City Hospital, Akron, OH; The EMMES Corporation, Rockville MD (Data Coordinating Center); University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL; University of Miami, Miami, FL; and University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregory EC, MacDorman MF, Martin JA. Trends in fetal and perinatal mortality in the United States, 2006–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(169):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFranco EA, Hall ES, Muglia LJ. Racial disparity in previable birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):394e391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander GR, Kogan M, Bader D, Carlo W, Allen M, Mor J. US birth weight/gestational age-specific neonatal mortality: 1995–1997 rates for Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e61–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen MC, Alexander GR, Tompkins ME, Hulsey TC. Racial differences in temporal changes in newborn viability and survival by gestational age. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14(2):152–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2000.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luke B, Brown MB. The changing risk of infant mortality by gestation, plurality, and race: 1989–1991 versus 1999–2001. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2488–2497. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willis E, McManus P, Magallanes N, Johnson S, Majnik A. Conquering racial disparities in perinatal outcomes. Clin Perinatol. 2014;41(4):847–875. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loftin R, Chen A, Evans A, DeFranco E. Racial differences in gestational age-specific neonatal morbidity: further evidence for different gestational lengths. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):259e251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Susan Berman DKR, Cohen Amy P, Pursley DeWayne M, Lieberman Ellice. Relationship of race and severity of neonatal illness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(4):668–672. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.109941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peacock JL, Marston L, Marlow N, Calvert SA, Greenough A. Neonatal and infant outcome in boys and girls born very prematurely. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(3):305–310. doi: 10.1038/pr.2011.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent AL, Wright IM, Abdel-Latif ME New South Wales and Austrailian Capital Territory Neonatal Intensive Care Units Audit Group. Mortality and adverse neurologic outcomes are greater in preterm male infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):126–131. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, et al. Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):326e321–326e310. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geronimus AT. Black/white differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: a population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(4):589–597. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weston EJ, Pondo T, Lewis MM, et al. The burden of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States, 2005–2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(11):937–941. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318223bad2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qureshi AI, Shafizadeh N, Majidi S. A 2-fold higher rate of intraventricular hemorrhage-related mortality in African American neonates and infants. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;12(1):49–53. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.PEDS12568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shankaran S, Maller-Kesselman J, Zhang H, O’Shea TM, Bada HS, Kaiser JR, Lifton RP, Bauer CR, Ment LR. Maternal race, demography, and health care disparities impact risk for intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm neonates. J Pediatr. 2014;164(5):1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perlman JM, Riser RC, Gee JB. Pregnancy-induced hypertension and reduced intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants. Pediatr Neurol. 1997;17(1):29–33. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(97)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lad EM, Nguyen TC, Morton JM, Moshfeghi DM. Retinopathy of prematurity in the United States. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(3):320–325. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.126201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders RA, Donahue ML, Christmann LM, et al. Racial variation in retinopathy of prematurity. The Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(5):604–608. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150606005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anadkat JS, Kuzniewicz MW, Chaudhari BP, Cole FS, Hamvas A. Increased risk for respiratory distress among white, male, late preterm and term infants. J Perinatol. 2012;32(10):780–785. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranganathan D, Wall S, Khoshnood B, Singh JK, Lee K. Racial differences in respiratory-related neonatal mortality among very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 2000;136(4):454–459. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhuri PK, MacDorman MF, Ezzati-Rice TM. Racial differences in leading causes of infant death in the United States. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahoney AD, Jain L. Respiratory disorders in moderately preterm, late preterm, and early term infants. Clin Perinatol. 2013;40(4):665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamed MA, Aly H. Impact of race on male predisposition to birth asphyxia. J Perinatol. 2014;34:449–452. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter BM, Holditch-Davis D. Risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: how race, gender, and health status contribute. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8(5):285–290. doi: 10.1097/01.ANC.0000338019.56405.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.