Abstract

We report an efficient means of sp –sp cross coupling for a variety of terminal monosubstituted olefins with aryl electrophiles using Pd and CuH catalysis. In addition to its applicability to a range of aryl bromide substrates, this process was also suitable for electron-deficient aryl chlorides, furnishing higher yields than the corresponding aryl bromides in these cases. The optimized protocol does not require the use of a glovebox and employs air-stable Cu and Pd complexes as precatalysts. A reaction on 10 mmol scale further highlighted the practical utility of this protocol. Employing a similar protocol, a series of cyclic alkenes were also examined. Cyclopentene was shown to undergo efficient coupling under these conditions. Lastly, deuterium-labeling studies indicate that deuterium scrambling does not take place in this sp2–sp3 cross coupling, implying that β-hydride elimination is not a significant process in this transformation.

Keywords: copper, palladium, cross-coupling, catalysis

Graphical Abstract

A protocol for sp2–sp3 cross coupling of terminal alkenes and aryl halides is described in this report. A broad substrate scope is detailed using air-stable precatalysts. Demonstration of this reaction on a 10 mmol scale is shown, along with preliminary studies with cyclic alkenes that highlight cyclopentene as an effective coupling partner as well. Lastly, deuterium-labeling studies probed the mechanism of aryl halide reduction and discounted evidence for a β-hydride elimination event.

Transition metal-catalyzed sp2–sp3 cross coupling has become a vibrant area of research due to its potential to serve as a strategic C–C bond forming process. Furthermore, this approach provides opportunities for appending fragments to complex, functionalized starting materials, thus expediting the synthesis of their analogs. Classically, a stoichiometric alkyl metal reagent is used as a coupling partner to enable facile transmetalation with a transition metal catalyst.1 Despite their synthetic utility, many of these methods suffer from promiscuous reactivity of the organometallic reagent and synthesis of the reagent is often nontrivial.

The palladium-catalyzed Suzuki cross coupling with alkylboron reagents is perhaps the most frequently utilized strategy for appending an alkyl fragment to an arene.2 In general, this approach has proven to be a versatile and reliable method that tolerates a broad range of functional groups. In addition, alkyl boron reagents are often readily accessible from the corresponding olefin via hydroboration.3 This method, however, suffers from several drawbacks with respect to the requisite boron reagents. In the case of trialkylboranes, the reagent is sensitive to air. Regarding more air-stable alkyl boronic acid/ester or trifluoroborate derivatives, multistep synthetic routes must often be employed for their preparation. Diminished synthetic efficiencies are also sometimes observed due to competitive β-hydride elimination of intermediate alkylpalladium(II) complexes. To address some of these deficiencies, several new strategies for alkyl-aryl cross coupling have been developed. Seminal reports by Fu demonstrated that alkyl halides can readily couple with aryl boronic acids with the use of a trialkylphosphine-supported palladium catalyst or a bipyridyl-supported nickel catalyst.4 In addition, palladium and nickel-catalyzed cross-electrophile strategies have allowed the coupling of alkyl halides with aryl electrophiles in the presence of an exogenous reductant.5, 6, 7, 8

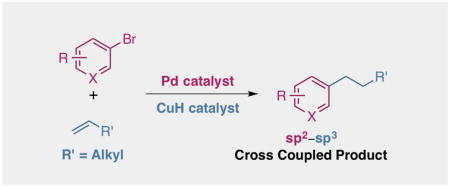

We reasoned that a complementary approach for sp2–sp3 cross coupling reactions using α-olefins as starting materials would allow us to overcome some of the shortcomings associated with the use of organoboron reagents and the limited commercial availability of alkyl halide coupling partners. Encouraged by a recent report from our lab9 and previous work utilizing Pd and Cu catalysis in a synergistic fashion,10 we envisioned that aryl halides and α-olefins could be brought together to form sp2–sp3 cross coupled products using a similar dual catalytic approach (Scheme 1). In particular, we rationalized that we could employ olefins as latent nucleophiles and, due to their stability and commercial availability, would serve as an attractive starting material for sp2–sp3 cross coupling. This formal reductive Heck reaction would thus provide access to useful compounds, albeit with perfect selectivity for the linear product.11

Scheme 1.

Pd- and CuH-catalyzed reductive cross coupling of terminal olefins with aryl electrophiles.

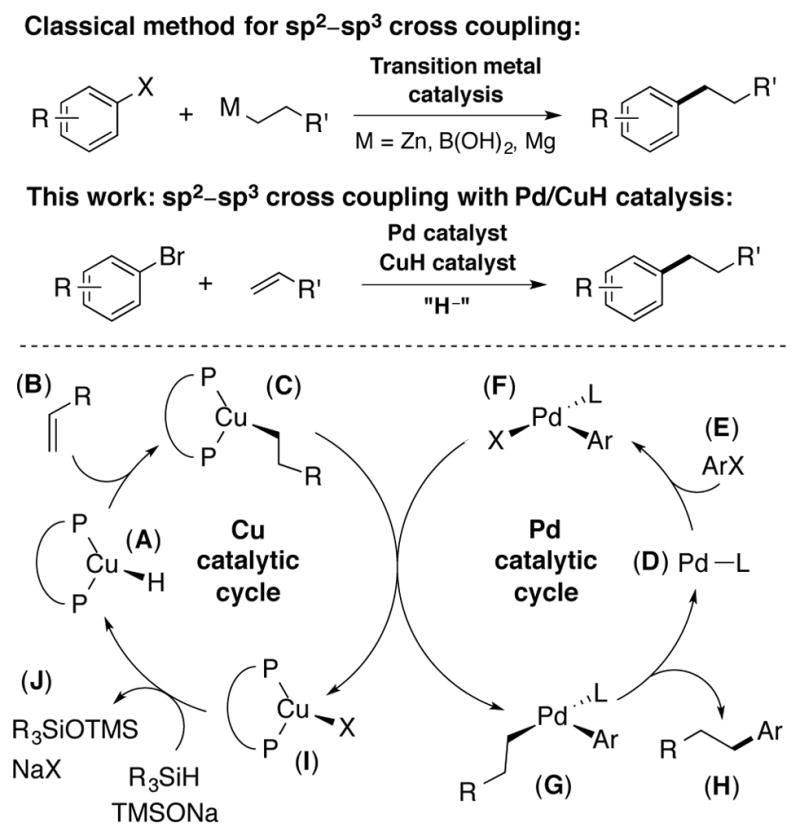

A detailed postulated mechanism of our strategy is shown in Scheme 1. Olefin insertion should readily occur in the presence of alkene B and CuH catalyst A to generate Cu(I)-alkyl C. In line with previous work,12 we believed that olefin insertion should occur in an anti-Markovnikov fashion with a simple α-olefin. Concomitant oxidative addition of Pd(0) D into aryl electrophile E would generate Pd(II) aryl complex F. Transmetalation between Cu(I)-alkyl C and Pd(II)-aryl F should furnish (alkyl)(aryl)palladium(II) complex G, which upon reductive elimination, would form the desired product and close the catalytic cycle for palladium. Base mediated regeneration of phosphine ligated CuH species A then closes the catalytic cycle for copper. For this proposed synergistic process to be successful, the rates of these two catalytic cycles would need to be matched to enable efficient catalysis to take place. In addition, palladium-catalyzed reduction/silylation of the aryl electrophile could also affect the overall efficiency of this process.

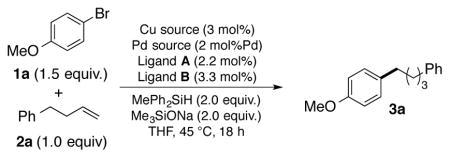

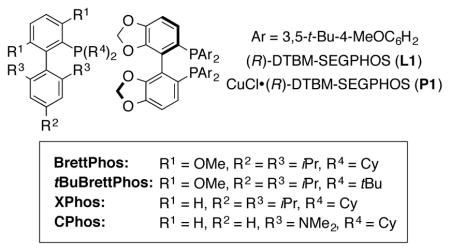

The optimization of this cross coupling protocol is detailed in Table 1. A series of ligands typically employed for Cu-catalyzed reactions were examined (entries 1–5), and a significant yield was observed only with DTBM-SEGPHOS (entry 5, 53% yield). Dialkylbiarylphosphine ligands have previously shown excellent activity as supporting ligands for Pd-catalyzed cross coupling reactions.13 Examination of several ligands of this family (entries 5–8) showed BrettPhos to be the most promising supporting ligand examined. CuCl was found to give the highest yield out of a variety of Cu(I) and Cu(II) salts tested (entries 5 and 9–11) (entry 11, 63% yield). A variety of Pd sources were also tested, with [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 providing the best reactivity (entry 11–14). Increasing the reaction temperature above 45 °C was not beneficial for product formation (entry 15, 56% yield). However, the use of Me2PhSiH as the silane provided a significant increase in the yield of the desired product, largely due to a decreased propensity for unproductive aryl halide reduction (entry 16, 78% yield). Importantly, we found that this reaction could be set up outside of the glovebox using air-stable DTBM-SEGPHOS-ligated CuCl precatalyst P1 when the loading of silane was increased slightly (entry 17, 75% isolated yield). This precatalyst retained full catalytic activity when stored for prolonged periods of time (>1 month) in a desiccator outside of the glovebox.14

Table 1.

Optimization of the Pd/Cu-catalyzed reductive cross coupling of terminal alkenes with aryl bromides

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Pd source | ligand A | Cu source | ligand B | yield, %[a] |

| 1 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | CuOAc | XantPhos | 5 |

| 2 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | CuOAc | BINAP | 6 |

| 3 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | CuOAc | PPh3 | 4 |

| 4 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | IPrCuCl | - | 0 |

| 5 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | CuOAc | L1 | 53 |

| 6 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | tBuBrettPhos | CuOAc | L1 | 26 |

| 7 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | XPhos | CuOAc | L1 | 40 |

| 8 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | CPhos | CuOAc | L1 | 9 |

| 9 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | Cu(OAc)2 | L1 | 33 |

| 10 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | CuBr | L1 | 61 |

| 11 | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | CuCl | L1 | 63 |

| 12 | Pd(OAc)2 | BrettPhos | CuCl | L1 | 35 |

| 13 | Pd2dba3 | BrettPhos | CuCl | L1 | 15 |

| 14 | Pd(COD)Cl2 | BrettPhos | CuCl | L1 | 23 |

| 15[b] | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | CuCl | L1 | 56 |

| 16[c] | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | CuCl | L1 | 78 |

| 17[d] | [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2 | BrettPhos | P1 | - | 79 (75) |

Yields determined by GC analysis of the crude reaction mixture using tetradecane as an internal standard, isolated yield is in parenthesis and is an average of two runs performed with 1 mmol of olefin.

Reaction run at 55 °C.

Me2PhSiH used as the silane.

Reaction was run outside of the glovebox and with 2.6 equiv. of Me2PhSiH as the silane.

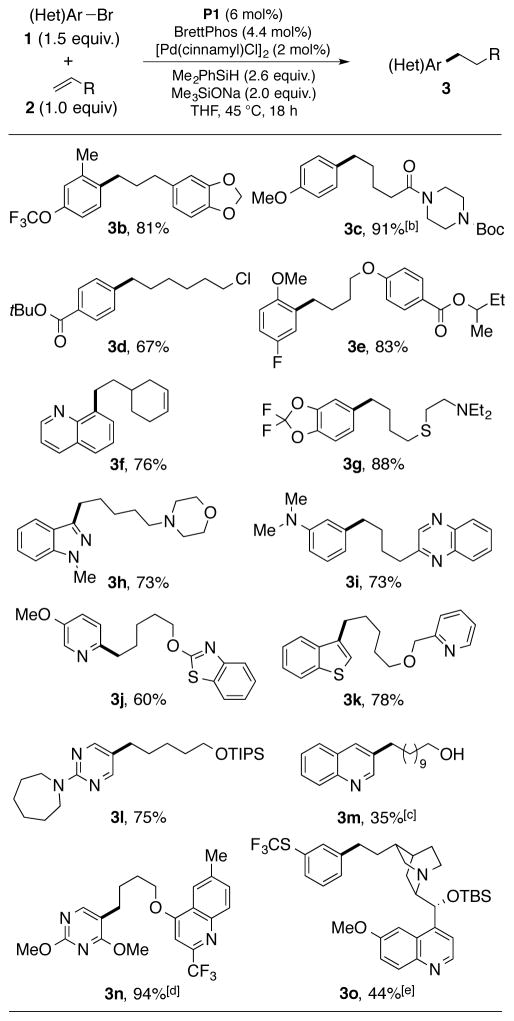

After optimization of our model reaction was completed, we examined the substrate scope of this protocol.15 A variety of functional groups were tolerated, including: ethers (such as 3b), an amide (3c), a carbamate (3c), esters (such as 3e), an alkyl chloride (3d), thioethers (such as 3g), amines (3g, 3h, and 3o), and silyl ethers (such as 3l). A free alcohol was tolerated (3m), but excess silane was required and the efficiency of the process was significantly diminished. The coupling of 2f displaying both a terminal and internal alkene proved highly selective for the more reactive α-olefin.

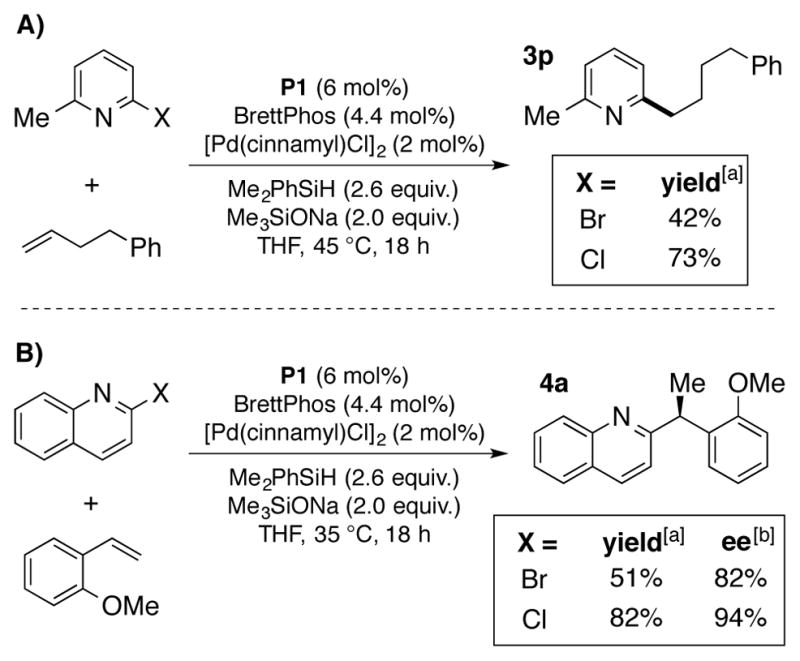

A series of heterocycles were also tolerated, including quinolines (3f, 3m, and 3o), an indazole (3h), an electron-rich pyridine (3j), a benzothiophene (3k), and electron-rich pyrmidines (3l and 3n). Electron-neutral and electron–rich aryl bromides generally perform well in this chemistry, while more electron-poor aryl and heteroaryl bromides proved to be problematic. For these substrates, the reduced aryl bromide was observed as a major side-product. We reasoned that electron-deficient aryl chlorides would be more recalcitrant to reduction in this chemistry, and could complement the aryl electrophile scope. In line with this rationale, 2-chloro-6-methylpyridine showed an enhanced efficiency in product formation over the corresponding bromide in the anti-Markovnikov hydroarylation of terminal olefins (Scheme 2A). This trend also applied to vinylarenes, with 2-chloroquinoline providing higher yield and enantioselectivity compared to 2-bromoquinoline in the hydroarylation of 2-vinylanisole (Scheme 2B).16

Scheme 2.

Comparison of electron-deficient aryl chlorides and bromides in Pd/CuH-catalyzed reductive cross coupling reactions; A) Anti-Markovnikov reductive cross coupling with α-olefins; B) Enantioselective Markovnikov hydroarylation of vinylarenes. [a] All yields represent the average of isolated yields from two runs performed with 1 mmol of olefin. [b] Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral HPLC.

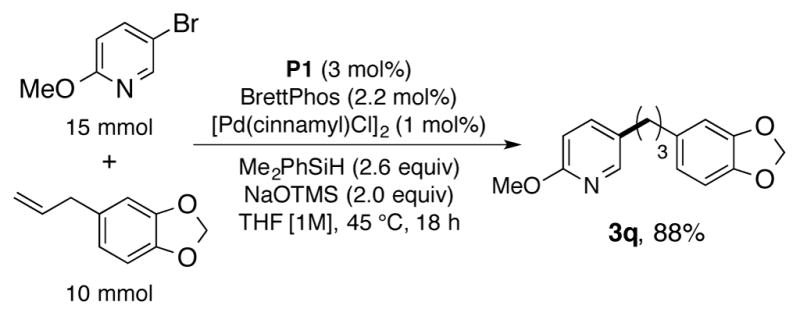

To highlight the practical utility of this transformation, a reaction was performed on a 10 mmol scale again without the aid of a glovebox. Even with lowered catalyst loadings (3 mol% Cu, 2 mol% Pd), the reaction exhibited excellent efficiency, providing the desired product 3q in a consistently high yield (Scheme 3, 2.4 grams, 88%).

Scheme 3.

Scale-up of the reductive cross coupling. Yields represent the average of isolated yields from two runs performed with 10 mmol of olefin.

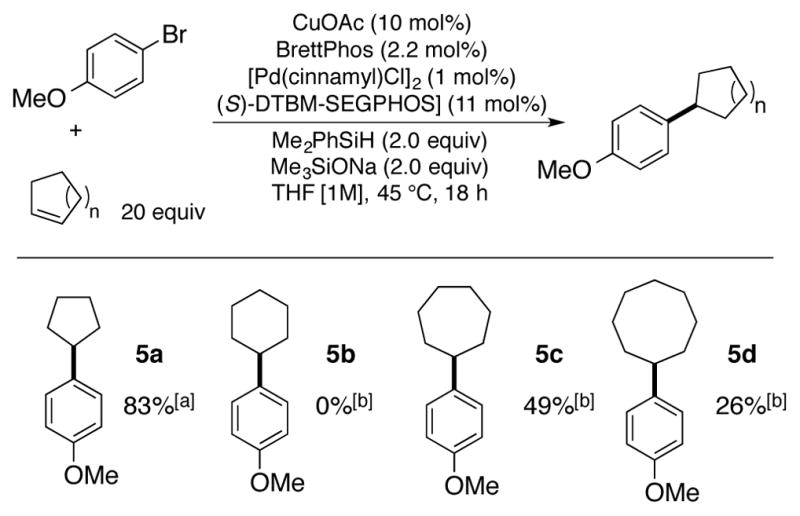

We were also interested in further exploring this chemistry with other classes of olefins. In particular, we investigated the use of cheap, readily available cyclic alkenes that could be used in excess for the synthesis of cross-coupled products containing cycloalkyl groups. This strategy would serve to both obviate the need for expensive cycloalkyl zinc reagents as required for the corresponding Negishi reactions while also simplifying the reaction setup.17 In this context, cyclopentene was found to couple in excellent efficiency with para-bromoanisole to afford product 5a. A high concentration of cyclopentene and copper catalyst was required for productive reactivity, presumably due to a more challenging hydrocupration step. Application of this protocol to alkenes of larger ring size led to reduced efficiency in the case of cycloheptene and cyclooctene, while cyclohexene was unreactive. We hypothesize that this trend is due to the decreased ring strain of the larger cyclic olefins, which reduces the propensity for the olefin to undergo hydrocupration with the CuH catalyst.18, 19

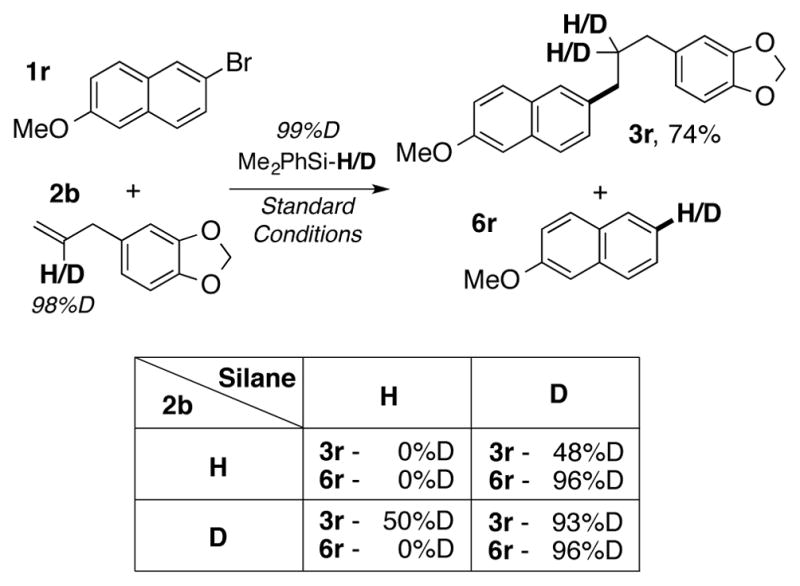

As mentioned above, aryl halide reduction constitutes the major unproductive side-reaction of this transformation. To this end, deuterium-labeling studies were pursued in this dual-catalyzed CuH/Pd protocol. We believed this could clarify two aspects of this chemistry: 1) the mechanism of aryl electrophile reduction and 2) whether the transient Cu(I)-alkyl or Pd(II)-alkyl aryl complex presumed to form during the course of the reaction undergo β-hydride elimination at any point (Scheme 1, C and G). The results of our study, using the four combinations of labeled and unlabeled silane and alkene, are displayed in Scheme 5. First, use of deuterated silane resulted in formation of deuterated arene 6r. We believe this implies that reduction of the aryl bromide occurs through a transmetalation event with the silane as the hydride source, rather than a β-hydride elimination/aryl-hydrogen reductive elimination sequence with the alkyl group as the ultimate source of the hydride (Scheme 1, G). Further confirming this hypothesis, deuterium scrambling was not observed when using a deuterated alkene, which indicates that β-hydride elimination from an organometallic alkyl complex is likely not taking place in this reaction.

Scheme 5.

Deuterium-labeling studies for the Pd/CuH-catalyzed reductive cross coupling of terminal alkenes with aryl bromides. Deuterium incorporation was quantified by 1H-NMR spectroscopy of the purified products.

In conclusion, we report the Cu/Pd-catalyzed reductive coupling of α-olefins and aryl electrophiles to form sp2–sp3 cross-coupled products. This protocol tolerates a broad range of functional groups and heterocycles, and does not require the preparation of any sensitive or specialized coupling partners. In addition, electron-deficient heteroaryl chlorides were shown to be effective in this reaction as well, complementing the efficiency observed for electron-rich and electron-neutral aryl bromides. The synthetic utility of this system was highlighted in a scale-up of the reaction to a 10 mmol scale using air-stable Cu and Pd precatalysts at reduced catalyst loadings. Studies using cyclic alkenes demonstrate that cyclopentene is also an effective coupling partner for this chemistry, likely due to the relief of ring-strain via hydrocupration. Finally, deuterium-labeling studies clarify the mechanism for aryl halide reduction and discount β-hydride elimination as a significant process in the protocol.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 4.

Investigation of cyclic alkenes as substrates in the Pd/CuH-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling. [a] Yield represents the average of isolated yields from two runs performed with 1 mmol of aryl bromide. [b] Yield determined by analysis of the crude reaction mixture via 1H-NMR spectroscopy using 1,3-benzodioxole as an internal standard.

Table 2.

Substrate scope for the Pd/Cu-catalyzed reductive cross coupling of monosubstituted olefins with aryl bromides.[a]

All yields represent the average of isolated yields from two runs performed with 1 mmol of olefin.

Reaction was run with 1 mol% [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2, 2.2 mol% BrettPhos, and 3 mol% P1.

Reaction run with 3.6 equiv of Me2PhSiH.

Reaction was run at 0.25 M.

Reaction was run at 0.5 M.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number GM46059. M.T.P. thanks the National Institutes of Health for a postdoctoral fellowship (1F32GM113311). S. D. F. thanks the Carlsberg Foundation and the Danish Council for Independent Research: Natural Sciences for postdoctoral fellowships (4181-00452). L. N. D. thanks the MIT Summer Research Program. We thank Sigma-Aldrich for the generous donation of BrettPhos ligand used in this work and Dr. Yiming Wang for his advice on the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- 1.a) de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. [Google Scholar]; b) Negishi E, editor. Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 2002. pp. 215–994. [Google Scholar]; c) Jana R, Pathak TP, Sigman MS. Chem Rev. 2011;111:1417. doi: 10.1021/cr100327p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Beller M, Bolm C, editors. Transition Metals for Organic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Miyaura N, Ishiyama T, Ishikawa M, Suzuki A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:6369. [Google Scholar]; b) Miyaura N, Ishiyama T, Sasaki H, Ishikawa M, Satoh M, Suzuki A. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:314. [Google Scholar]; c) Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2457. [Google Scholar]; d) Doucet H. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:2013. [Google Scholar]; e) Lennox AJJ, Lloyd-Jones GC. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:412. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60197h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown HC, editor. Organic Syntheses via Boranes. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Kirchhoff JH, Netherton MR, Hills ID, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13662. doi: 10.1021/ja0283899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhou JS, Gu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1340. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Everson DA, Johnes BA, Weix DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6146. doi: 10.1021/ja301769r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang S, Qian Q, Gong H. Org Lett. 2012;14:3352. doi: 10.1021/ol3013342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Molander GA, Traister KM, O’Neill BT. J Org Chem. 2014;79:5771. doi: 10.1021/jo500905m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bhonde VR, O’Neill BT, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:1849. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For additional selected examples of reductive Pd-catalyzed cross coupling, see: Gligorich KM, Cummings SA, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14193. doi: 10.1021/ja076746f.Iwai Y, Gligorich KM, Sigman MS. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:3219. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705317.Gligorich KM, Iwai Y, Cummings SA, Sigman MS. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:5074. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.03.096.

- 7.For other recent approaches for transition metal-catalyzed aryl-alkyl cross coupling, see: Toriyama F, Cornella J, Wimmer L, Chen TG, Dixon DD, Creech G, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:11132. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07172.Cornella J, Edwards JT, Qin T, Kawamura S, Wang J, Pan CM, Gianatassio R, Schmidt M, Eastgate MD, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:2174. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00250.Wang J, Qin T, Chen T-G, Wimmer L, Edwards JT, Cornella J, Vokits B, Shaw SA, Baran PS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:9676. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605463.Zuo Z, Ahneman DT, Chu L, Terrett JA, Doyle AG, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2014;345:437. doi: 10.1126/science.1255525.Zuo Z, Cong H, Li W, Choi J, Fu GC, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1832. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13211.Shaw MH, Shurtleff VW, Terrett JA, Cuthbertson JD, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2016;352:1304. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6635.Zhang P, Le CC, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:8084. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04818.Shields BJ, Doyle AG. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:12719. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08397.Ahneman DT, Doyle AG. Chem Sci. 2016;7:7002. doi: 10.1039/c6sc02815b.Jouffroy M, Primer DN, Molander GA. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:475. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10963.Tellis JC, Primer DN, Molander GA. Science. 2014;345:433. doi: 10.1126/science.1253647.

- 8.Work by Nakao, Hiyama, and Hartwig, as well as Fu and Liu, has employed nickel catalysis for the hydroarylation of terminal alkenes, although the substrate scope is limited. See: Nakao Y, Kashihara N, Kanyiva KS, Hiyama T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:4451. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001470.Blair JS, Schramm Y, Sergeev AG, Clot E, Eisenstein O, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:13098. doi: 10.1021/ja505579f.Schramm Y, Takeuchi M, Semba K, Nakao Y, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:12215. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08039.Lu X, Xiao B, Zhang Z, Gong T, Su W, Yi J, Fu Y, Liu L. Nature Comm. 2016;7:11129. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11129.

- 9.Friis SD, Pirnot MT, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:8372. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Sonogashira K, Tohda Y, Hagihara N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;16:4467. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jabri N, Alexakis A, Normant JF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:959. [Google Scholar]; (c) Liebeskind LS, Fengl RW. J Org Chem. 1990;55:5359. [Google Scholar]; (d) Huang J, Chan J, Chen Y, Borths CJ, Baucom KD, Larsen RD, Faul MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3674. doi: 10.1021/ja100354j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chinchilla R, Nájera C. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5084. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15071e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nahra F, Macé Y, Lambin D, Riant O. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:3208. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Vercruysse S, Cornelissen L, Nahra F, Collard L, Riant O. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:1834. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Nahra F, Macé Y, Boreux A, Billard F, Riant O. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:10970. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Ratniyom J, Dechnarong N, Yotphan S, Kiatisevi S. Eur J Org Chem. 2014:1381. [Google Scholar]; (j) Semba K, Nakao Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:7567. doi: 10.1021/ja5029556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Smith KB, Logan KM, You W, Brown MK. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:12032. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Logan KM, Smith KB, Brown MK. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:5228. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Jia T, Peng C, Wang B, Lou Y, Yin X, Wang M, Liao J. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13760. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Semba K, Ariyama K, Zheng H, Kameyama R, Sakaki S, Nakao Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:6275. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For a general overview on the Heck reaction, see: Tsuji J. Palladium Reagents and Catalysts: New Perspectives for the 21st Century. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2004. pp. 109–431.

- 12.(a) Dang L, Zhao H, Lin Z, Marder TB. Organometallics. 2007;26:2824. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhu S, Niljianskul N, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:15746. doi: 10.1021/ja4092819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhu S, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:15913. doi: 10.1021/ja509786v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Chem Sci. 2011;2:27. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00331J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Previous use of precatalysts for CuH catalysis: Bandar JS, Pirnot MT, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14812. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10219.Wang YM, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5024. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02527.

- 15.An increased catalyst loading of 4 mol% Pd and 6 mol% Cu was found to be necessary for more complex substrates.

- 16.The absolute configuration of 4a was assigned by analogy in accordance with reference 5.

- 17.Haas D, Hammann JM, Greiner R, Knochel P. ACS Catal. 2016;6:1540. [Google Scholar]

- 18.For general information about ring strain of cyclic alkenes, see: Anslyn EV, Dougherty DA. Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books; 2006. pp. 110–112.Robert JD, Caserio MC. Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry. W. A. Benjamin, Inc; Menlo Park: 1977. pp. 474–476.

- 19.The ring strain argument is reasonable for the cyclopentene and cyclohexene comparison but is not clearly suitable for the lesser reactivity observed with cycloheptene and cyclooctene. In these cases, hydrocupration could be reasoned to be less favoured due to the increased steric encumbrance of the larger-sized cyclic alkenes.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.