ABSTRACT

The second messenger cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) is almost ubiquitous among bacteria as are the c-di-GMP turnover proteins, which mediate the transition between motility and sessility. EAL domain proteins have been characterized as c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterases. While most EAL domain proteins contain additional, usually N-terminal, domains, there is a distinct family of proteins with stand-alone EAL domains, exemplified by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium proteins STM3611 (YhjH/PdeH), a c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase, and the enzymatically inactive STM1344 (YdiV/CdgR) and STM1697, which regulate bacterial motility through interaction with the flagellar master regulator, FlhDC. We have analyzed the phylogenetic distribution of EAL-only proteins and their potential functions. Genes encoding EAL-only proteins were found in various bacterial phyla, although most of them were seen in proteobacteria, particularly enterobacteria. Based on the conservation of the active site residues, nearly all stand-alone EAL domains encoded by genomes from phyla other than proteobacteria appear to represent functional phosphodiesterases. Within enterobacteria, EAL-only proteins were found to cluster either with YhjH or with one of the subfamilies of YdiV-related proteins. EAL-only proteins from Shigella flexneri, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Yersinia enterocolitica were tested for their ability to regulate swimming and swarming motility and formation of the red, dry, and rough (rdar) biofilm morphotype. In these tests, YhjH-related proteins S4210, KPN_01159, KPN_03274, and YE4063 displayed properties typical of enzymatically active phosphodiesterases, whereas S1641 and YE1324 behaved like members of the YdiV/STM1697 subfamily, with Yersinia enterocolitica protein YE1324 shown to downregulate motility in its native host. Of two closely related EAL-only proteins, YE2225 is an active phosphodiesterase, while YE1324 appears to interact with FlhD. These results suggest that in FlhDC-harboring beta- and gammaproteobacteria, some EAL-only proteins evolved to become catalytically inactive and regulate motility and biofilm formation by interacting with FlhDC.

IMPORTANCE The EAL domain superfamily consists mainly of proteins with cyclic dimeric GMP-specific phosphodiesterase activity, but individual domains have been classified in three classes according to their functions and conserved amino acid signatures. Proteins that consist solely of stand-alone EAL domains cannot rely on other domains to form catalytically active dimers, and most of them fall into one of two distinct classes: catalytically active phosphodiesterases with well-conserved residues of the active site and the dimerization loop, and catalytically inactive YdiV/CdgR-like proteins that regulate bacterial motility by binding to the flagellar master regulator, FlhDC, and are found primarily in enterobacteria. The presence of apparently inactive EAL-only proteins in the bacteria that do not express FlhD suggests the existence of additional EAL interaction partners.

KEYWORDS: cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase, flagellar regulon, motility, protein-protein interaction, FlhDC

INTRODUCTION

Cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) is a ubiquitous secondary messenger in bacteria that is involved in the transitions between motility and sessility and between acute and chronic infections (1, 2). c-di-GMP turnover is mediated by diguanylate cyclases, which contain the GGDEF domain, and c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs), which include either the EAL or the HD-GYP domain (1, 3). Along with the GGDEF domain, the EAL domain is one of the most common domains encoded in bacterial genomes (4, 5). Recent studies of the EAL domain sequences and structures provided significant insights into the mechanism of its PDE activity (1, 6, 7). These studies characterized a number of EAL domains that functioned as c-di-GMP-specific PDEs and also some inactivated domains that were devoid of enzymatic activity (8–10). Based on the conservation of the active-site motifs and the dimerization loop (11), EAL domains have been categorized into three main classes: (i) bona fide c-di-GMP PDEs, (ii) EAL domains with a degenerate loop 6 that might or might not have PDE activity, and (iii) EAL domains that lack the key catalytic residues and have no enzymatic activity (11, 12). The latter class could be further subdivided into those EAL domains that have retained the ability to bind c-di-GMP and serve as c-di-GMP receptors and those domains that do not even bind c-di-GMP (9, 10, 13, 14).

Most EAL domain proteins contain N-terminal signaling domains that regulate the formation of catalytically active dimers (6, 15, 16). However, some EAL-containing proteins do not include any other domains and therefore represent stand-alone EAL domains. In fact, the first reports on the EAL-containing proteins all dealt with stand-alone EAL domains, including (i) an unnamed open reading frame, URF2, next to the mercury resistance operons of plasmid R100 and transposon Tn501 (17), (ii) ToxR/RegA, a positive regulator of exotoxin A expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (18, 19), and (iii) BvgR, a regulator of virulence-related genes in Bordetella pertussis (20) (Fig. 1). However, in each of these cases, the regulatory mechanisms remain obscure.

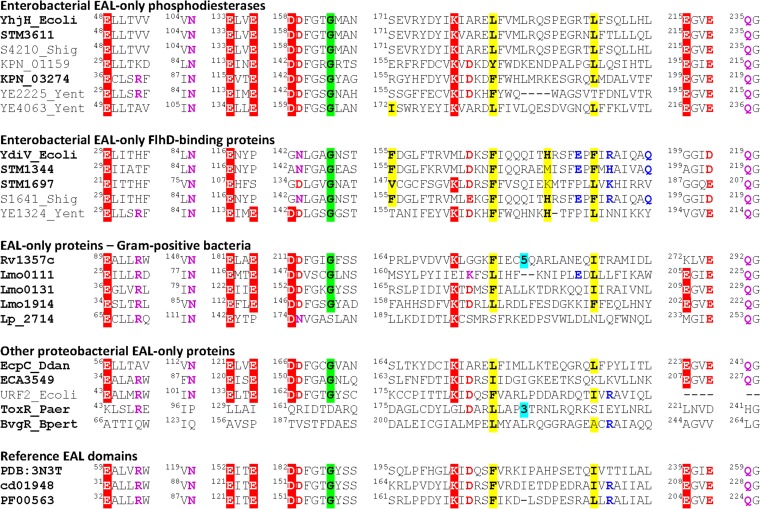

FIG 1.

Conservation of the active site, dimerization loop, and the FlhD-binding residues among EAL-only proteins. The first two blocks represent enterobacterial EAL-only PDEs and enterobacterial catalytically inactive FlhD-binding EAL-only proteins from strains investigated in this work. These proteins from S. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028, E. coli K-12, S. flexneri 2a, K. pneumoniae, and Y. enterocolitica are listed under their names in the NCBI protein database; the respective GenBank accession numbers are listed in Table S4 in the supplemental material. Experimentally characterized EAL-only proteins of Gram-positive Actinomycetes and Firmicutes come from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Rv1357c [73, 74]), Listeria monocytogenes (Lmo0111, Lmo0131, and Lmo1914 [30]), and the catalytically inactive Lp_2714 from Lactobacillus plantarum (75). Other proteobacterial EAL-only proteins include experimentally characterized proteins from Dickeya dadantii (EcpC_Ddan [28]), ECA3549 from Pectobacterium atrosepticum (76), and the first sequenced stand-alone EAL proteins URF2 from E. coli (GenBank accession no. AAA83542), ToxR/RegA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (AAG04096), and BvgR from Bordetella pertussis (AAC23902) (17–20). Reference EAL domain sequences are from the Thiobacillus denitrificans protein TBD1265 (PDB entry 3N3T), NCBI's Conserved Domain Database entry cd01948, and the Pfam domain PF00563 (7, 39, 60). The residues that form the active site of c-di-GMP PDEs (7, 8) are shown in white on a red background; conserved residues located in the vicinity of the active site are in red or magenta. The hydrophobic residues that participate in YdiV-FlhD binding (35) are shaded yellow, and charged residues at that interface are in blue. Names of previously experimentally characterized proteins are in bold.

The discovery of the multidomain PAS-GGDEF-EAL proteins of Acetobacter xylinum (now Komagataeibacter xylinus) participating in c-di-GMP turnover (21) stimulated detailed studies of the enzymatic properties of the EAL domains and their interactions with c-di-GMP (reviewed in reference 1). Stand-alone EAL domain proteins attracted far less attention. Still, an EAL-only protein, PA2133, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (22, 23), two such proteins encoded in Escherichia coli K-12, and three encoded in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium have been experimentally characterized (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The E. coli protein YhjH (recently renamed PdeH [24]) and its close homolog STM3611 from S. Typhimurium (79% identity at the protein level) have been shown to be active c-di-GMP-specific PDEs involved in the regulation of cell motility (9, 25, 26). Similar effects of YhjH orthologs have been reported in Aeromonas veronii, Dickeya dadantii, and Klebsiella pneumoniae (27–29). More recently, three EAL-only proteins from the Gram-positive pathogen Listeria monocytogenes were shown to possess c-di-GMP PDE activity (30).

By contrast, the E. coli protein YdiV (alternatively named RflP [24]) and its S. Typhimurium counterparts STM1344 (CdgR) and STM1697 consist of diverged EAL domains that lack the key active site residues (Fig. 1). These proteins display no detectable PDE activity, do not readily form dimers, and do not bind c-di-GMP (9, 10), falling into class 3b of the above-mentioned classification (12). Nevertheless, these proteins have been shown to regulate motility and cell adherence and affect bacterial cytotoxicity towards macrophages (9, 10, 31, 32). This regulation involves a direct interaction with the FlhD component of FlhD4C2, the master regulator of flagellar gene expression, to prevent the interaction of FlhD4C2 with DNA and to stimulate proteolysis by the ClpXP protease (10, 33, 34). The structures of stand-alone YdiV and the YdiV-FlhD complex have been solved, providing an insight into the mechanism of this regulatory interaction (35). Three more EAL-only proteins, the S. Typhimurium protein STM1697 and the L. monocytogenes PDEs Lmo0111 and Lmo0131 (Fig. 1), have been structurally characterized.

In addition to experiments in mice (10, 31, 36) and cytotoxicity data from the Chinese hamster ovary cell line (22), several other observations support the involvement of EAL-only proteins in bacterial pathogenesis. An EAL-only-encoding gene, sfaYII, is part of a pathogenicity island in a newborn meningitis E. coli isolate and its expression in Vibrio cholerae has been shown to affect biofilm formation (37). Similar EAL-only proteins PdeW, PdeX, and PdeY have been found encoded in the genomes of various enteropathogenic and enterotoxigenic strains of E. coli (38).

In S. Typhimurium, we have observed that EAL-only proteins, despite a significant divergence in functionality (Fig. S1), are phylogenetically more closely related to each other than to EAL proteins with an additional N-terminal and/or GGDEF domain (see Fig. S2). We were therefore wondering to what extent macro- and microevolution occur in EAL-only proteins beyond S. Typhimurium. Thus, this work extends the characterization of evolutionary relationship versus functionality of stand-alone EAL domain proteins beyond S. Typhimurium to include analyses of such proteins from several other enterobacterial pathogens.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic distribution of EAL-only proteins.

According to the Pfam database (39), almost one-fifth of the EAL-containing proteins (Pfam family PF00563) listed in UniProt (40) do not include any other (known) domains. The NCBI's CDART tool (41) reports similar numbers. However, many of these proteins are not stand-alone EAL domains, as they contain long unannotated segments, which likely represent uncharacterized protein domains. Thus, the recently identified CSS motif domain is found in five formerly EAL-only proteins in E. coli K-12 (24) and also in five EAL proteins in S. Typhimurium. However, even limiting the protein lengths in the NCBI protein database to 280 amino acid residues and filtering out truncated fragments still leaves ∼20,000 sequences that represent true stand-alone EAL domain proteins. This is in sharp contrast to the GGDEF domain-containing proteins, where fewer than 200 (∼0.03% of the total) represent GGDEF-only proteins. EAL-only domain proteins are encoded in the genomes of representatives of most well-sequenced bacterial phyla, including Actinobacteria, Aquificae, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Spirochaetes (see Table S4a in the supplemental material). The largest numbers of EAL-only proteins are found in gammaproteobacteria, particularly in enterobacteria, where they often comprise more than 10% of all EAL-containing proteins (see Table S4b). In some bacterial groups, such as lactobacilli and listeria, all EAL-containing proteins appear to be stand-alone EAL domains (see Table S4c). It should be noted that the active site residues responsible for the PDE activity (Fig. 1) are remarkably well conserved in the majority of EAL-only proteins expressed by groups other than proteobacteria (see Fig. S3). The sequences of the dimerization loop are also conserved, albeit deviating somewhat from the consensus pattern described previously (11).

Clustering of enterobacterial EAL-only proteins.

The chromosome of S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028 (42) encodes a total of 20 GGDEF and/or EAL domain proteins, which regulate, for example, the red, dry, and rough (rdar) biofilm phenotype, biofilm formation, bistability, motility, and virulence properties in cell culture systems, mammals, and plants (10, 43–47). Of these twenty, 15 proteins contain EAL domains and three of them, STM1344, STM1697 and STM3611, represent stand-alone EAL domains that are all involved in the regulation of motility in S. Typhimurium (10, 46). We have previously reported that STM1344 (YdiV) and STM3611 (YhjH) proteins were more closely related to each other than to other EAL domains of S. Typhimurium and branched together on the phylogenetic tree of the EAL domains (46). This observation has now been confirmed by constructing a maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic tree of all EAL domains of S. Typhimurium (Fig. S2). In addition to these 15 EAL-containing proteins, the genome of S. Typhimurium strain ATCC 14028 encodes two truncated EAL domains, STM0551 (77) and plasmid-encoded PSLT032, which have not been studied in this work.

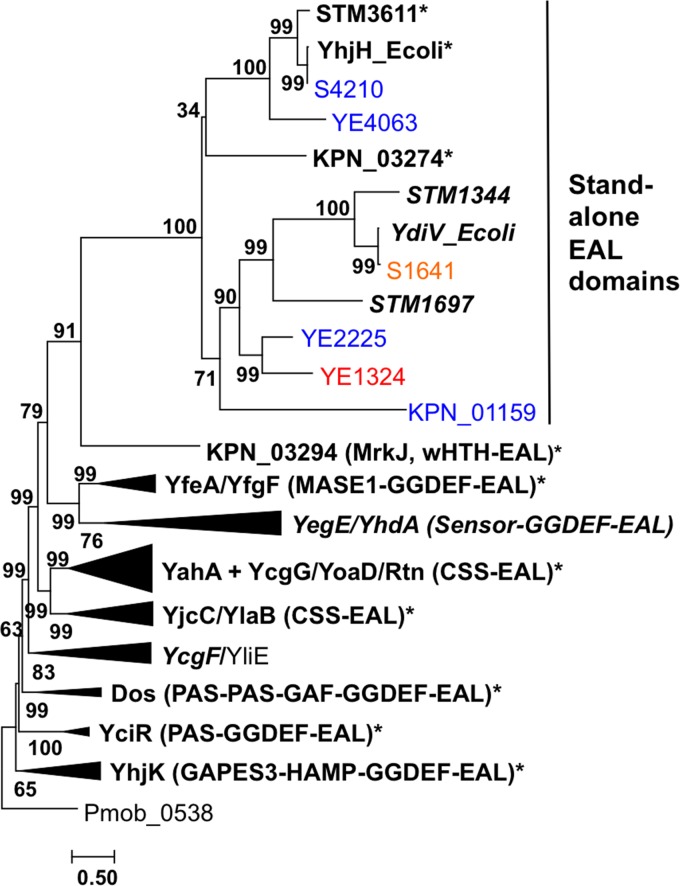

BLAST searches of enterobacterial genome sequences showed that they encode from zero to eight EAL-only proteins (Table S4b). Remarkably, EAL-only proteins from S. Typhimurium, E. coli K-12, Shigella flexneri, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Yersinia enterocolitica formed a well-defined branch on the phylogenetic tree of the EAL domain sequences from these bacteria, separate from those of the EAL domains coming from multidomain proteins (Fig. 2; see also Table S5). Furthermore, the EAL-only cluster was still preserved after the addition of EAL domain proteins from a variety of other enterobacteria (see Fig. S4). While most of these proteins clearly fell into either YhjH (STM3611 and PdeH) or YdiV (STM1344, CdgR, or RflP) subfamilies, additional subfamilies showed up, particularly in such organisms as Citrobacter koseri, Enterobacter asburiae, and Shigella boydii, which encode more than three EAL-only proteins. Based on the conservation of the active site residues (Fig. 1), members of the YhjH/PdeH subfamily could be predicted to function as enzymatically active PDEs (class I EAL-only domain), whereas members of the YdiV/CdgR/RflP subfamily had active site substitutions incompatible with PDE activity (class III EAL-only domain). At the same time, the residues identified in the crystal structure of the YdiV-FlhD complex (35) as important for the interaction between these two proteins are well conserved among the members of the YdiV family (Fig. 1). Finally, several stand-alone EAL domains have substitutions in both the active site residues and the residues at the YdiV-FlhD interface, making them unlikely to either have the PDE activity or be able to bind FlhD (Fig. 1).

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic tree of enterobacterial EAL domain proteins. EAL domain sequences from S. Typhimurium, E. coli, S. flexneri, K. pneumoniae, and Y. enterocolitica (see Fig. S4 for the complete tree with accession numbers and domain boundaries) were aligned with MUSCLE (61) and a maximum likelihood tree was built using PhyML (63), with automatic selection of the best-fit substitution model and branch support values estimated using the aBayes algorithm (64). The tree was rooted using the sequence of an EAL domain from Petrotoga mobilis, a member of the phylum Thermotogae. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths corresponding to the numbers of substitutions per site, and visualized with MEGA7 (62). The branches leading to the multidomain proteins with identical domain compositions have been collapsed and marked with the names of their E. coli members and domain architectures as listed in reference 24. Names of previously experimentally characterized proteins are in bold. Those with demonstrated phosphodiesterase activity against c-di-GMP are marked with asterisks; those shown not to hydrolyze c-di-GMP are in italic font. Enterobacterial stand-alone EAL domains characterized in this work are shown in normal font (blue, PDE activity; red, catalytic activity is lacking).

Functionality of the EAL-only proteins.

To test functional assignments of the EAL-only proteins expressed in other enterobacteria, representative strains from three different species with completely sequenced genomes, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae MGH 78578, Shigella flexneri 2a strain 24570T, and Yersinia enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica 8081 (48, 49), were chosen. The first two organisms are nonmotile, while Y. enterocolitica is motile. Their chromosomes encode, respectively, two (KPN_01159 and KPN_03274), two (S1641 and S4210), and three (YE1324, YE2225, and YE4063) EAL-only proteins (see Table S5 for accession numbers). The plasmid-encoded EAL-only protein KPN_pKPN4p07065 of K. pneumoniae was not a subject of this investigation. These proteins were classified as follows: S4210, KPN_01159, KPN_03274, and YE4063 belong to the YhjH/STM3611 subfamily, and S1641 belongs to the YdiV/STM1344 subfamily (Fig. 1 and 2; see also Fig. S4). The closely related proteins YE2225 and YE1324 do not fall into either of these subfamilies; the former contains the full set of active site residues, whereas the latter lacks a catalytically important Glu residue (Fig. 1).

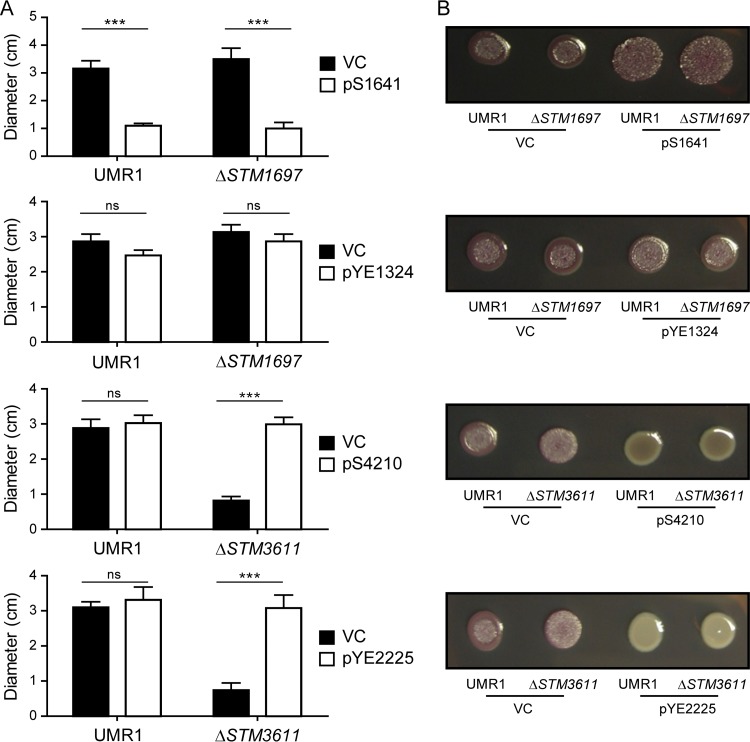

We started the functional characterization of these proteins by assessing the phenotype changes in biofilm formation and motility upon their overexpression in well-established models of S. Typhimurium. As described previously (50), the expression of enzymatically active PDEs is indicated by a downregulation of the rdar morphotype biofilm on Congo red agar plates and a minor upregulation of motility in the wild-type background (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S5). Accordingly, the expression of non-PDE YdiV/STM1344/STM1697-like proteins that interact with FlhD is indicated by opposite phenotypes, namely, an upregulation of the rdar biofilm morphotype and a downregulation of motility in the wild-type background. As the phenotypic change in motility in the wild type is not always informative, the functionality of PDEs was also assessed in deletion mutants. Deletion of the PDE-encoding STM3611 (yhjH or pdeH) gene resulted in significantly suppressed motility, which could be robustly restored upon overexpression of a functional PDE. On the other hand, catalytically nonfunctional EAL proteins were expected to robustly suppress motility in the ΔSTM1697 mutant background. To summarize these tests, the expression of KPN_01159, KPN_03274, S4210, and YE4063 proteins led to the downregulation of the rdar morphotype biofilm in the wild type and restoration of motility in the ΔSTM3611 mutant background (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S5). Thus, in full accordance with their placement on the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2), these proteins displayed behaviors typical of active PDEs. The expressed S1641 behaved like an YdiV/STM1344-type protein (Fig. 3), as it downregulated motility and upregulated the rdar morphotype (Fig. 3), a phenotype that again correlates with its phylogenetic position.

FIG 3.

Effect of EAL-only protein expression on S. Typhimurium UMR1 motility and rdar morphotype formation. (A) Effect of EAL-only proteins on motility in 0.3% LB agar incubated at 37°C for 5 h measured by colony diameter. Data from three independent experiments were averaged and the standard errors of the means are presented. ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant. S1641 and YE1324 were overexpressed in both a UMR1 wild type and an ΔSTM1697 background, while S4210 and YE2225 were overexpressed in the wild type and a ΔSTM3611 background. VC (vector control) is pSRKGm. All genes were cloned in pSRKGm. (B) Effect of EAL domain proteins on rdar morphotype formation in S. Typhimurium UMR1. Congo red agar plates were incubated for 48 h at 28°C.

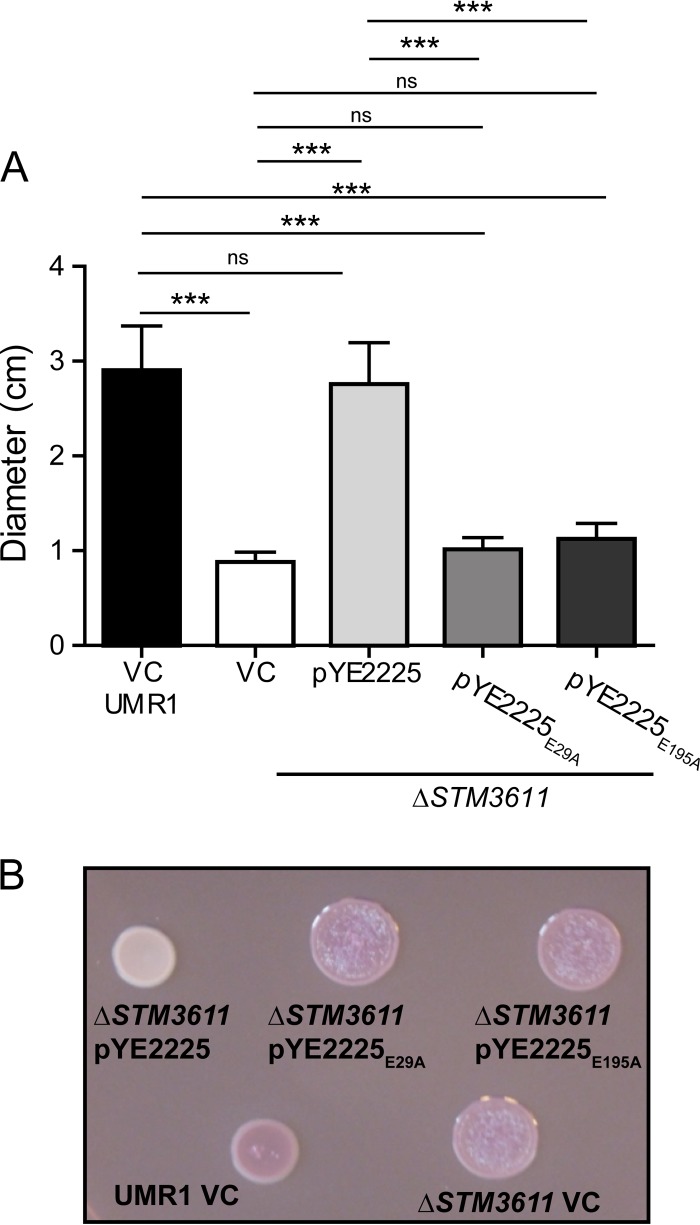

The two closely related Yersinia proteins, YE1324 and YE2225, which formed a separate branch in the YhjH (active PDEs) part of the tree (Fig. 2), were investigated in more detail. YE2225 showed a typical PDE phenotype; when expressed in the ΔSTM3611 mutant, it restored the motility defect and downregulated the rdar morphotype. This phenotypic pattern is in accordance with the conservation of all the core active site residues (Fig. 1 and 3). To confirm that the phenotypic effects of YE2225 depended on its ability to function as a PDE, the catalytically important Glu29 and Glu195 of the EAL and EGVE motifs, respectively, were replaced by alanines, two changes that were previously shown to generate catalytically inactive EAL domains (7). Indeed, the expression of the resulting YE2225E29A and YE2225E195A mutant proteins in S. Typhimurium did not restore the motility defect of an S. Typhimurium ΔSTM3611 (ΔyhjH) mutant and, accordingly, did not cause a downregulation of the rdar morphotype in the wild-type strain or the ΔSTM3611 (ΔyhjH) mutant (Fig. 4), consistent with YE2225 functioning as a PDE in vivo.

FIG 4.

Mutant analysis of Y. enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica 8081 YE2225 PDE. Effects of mutants YE2225E29A and YE2225E195A on motility and biofilm formation. (A) Motility assay in S. Typhimurium was performed in 0.3% LB agar generate. Single clones were stabbed into the agar and plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 h. YE2225 overexpression in the ΔSTM3611 mutant complemented the reduced-motile phenotype, while neither YE2225E29A nor YE2225E195A rescued the reduced-motile phenotype of the ΔSTM3611 mutant. Data from three independent experiments are averaged, and the standard errors of the means are presented. ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significant. (B) Effect of YE2225 on rdar morphotype expression in S. Typhimurium. Congo red plates were incubated for 24 h at 28°C. VC, vector control pSRKGm. All genes were cloned in pSRKGm.

The other Yersinia protein, YE1324, which had amino acid replacements in the catalytically important Glu194 of the EGVE motif and in several amino acid residues at the EAL-FlhD interface (Fig. 1), upregulated the rdar morphotype and showed a trend in downregulation of motility, although not statistically significant (Fig. 3). This finding indicates that EAL-only proteins may have additional regulatory modes that differ from the YhjH and YdiV paradigm.

Functionality of proteins in their respective hosts.

Although the phenotypes of EAL-only proteins in S. Typhimurium suggest a certain functionality, a different functionality in their respective native hosts could not be excluded. Therefore, we performed experiments in Shigella and Y. enterocolitica.

Shigella is considered to be nonmotile; however, remnants of a flagellar regulon with partially functional components can still be present in certain strains (51, 52). Indeed, limited expression of flagella and motility has been reported in Shigella isolates (53). Using S. flexneri 2a strain 24570T and 10 Shigella sp. clinical isolates, we observed apparent regain of motility in low percentage soft agar, which was, however, not consistent among the isolates (see Fig. S6). We investigated whether protein S1641, which effectively inhibited motility in S. Typhimurium, and S4210, with predicted PDE activity, had impacts on the apparent motility of clinical isolates. In two different clinical isolates with a motility phenotype, the overexpression of S1641 and S4210 did not lead to phenotypic alterations (Fig. S6 and data not shown). Why these two proteins retained functionality, while the flagellar regulon is nonfunctional in Shigella, remains to be investigated.

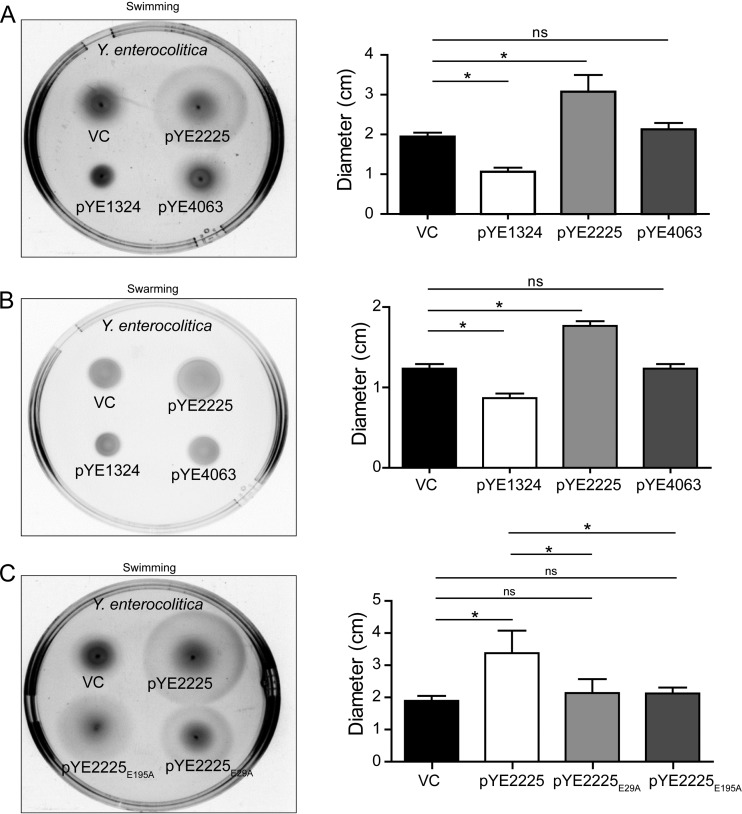

Y. enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica 8081 is motile at 25°C. Thus, we tested the impacts of YE1324, YE2225, and YE4063 on motility in the native host at this temperature (Fig. 5). While YE1324 suppressed, and YE2225 upregulated, swimming and swarming motility, YE4063 did not discernibly change the phenotype of Y. enterocolitica at 25°C. For YE2225, these data are consistent with the predicted function and the phenotype as observed in S. Typhimurium. The lack of a phenotype in motility for YE4063 in Y. enterocolitica compared with that in S. Typhimurium suggests a function other than motility for this PDE in its native host. On the other hand, the statistically significant repression of motility by YE1324 in Y. enterocolitica suggests interference with the flagellar regulon. The role of PDE YE2225 in motility was further investigated. In agreement with the phenotypes displayed in S. Typhimurium, YE2225 upregulated motility, but the mutant proteins YE2225E29A and YE2225E195A did not alter motility in the Y. enterocolitica wild type, consistent with YE2225 being a PDE that affects motility through its c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity but not as a protein that interacts with FlhD of the flagellar master regulator (Fig. 5C).

FIG 5.

Motility phenotypes upon YE2225, YE1324, and YE4063 overexpression in Y. enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica 8081. (A) Swimming motility assay was performed in 0.2% TB0 agar supplemented with 10 mM glucose. Single colonies were stabbed into the agar and plates were incubated at 25°C for 18 h. A representative image of motility behavior is presented. (B) Swarming motility assay was performed on 0.3% TB0 Eiken agar incubated at 25°C for 20 h. A representative image of the swarming behavior is shown. (C) Motility assay of the YE2225 PDE and YE2225E29A and YE2225E195A mutants. Swimming motility was assessed in 0.2% TB0 agar with 10 mM glucose. Single colonies were stabbed into the agar and plates were incubated at 25°C for 18 h. Representative image of motility behavior is presented. Data are means from three independent experiments and bars indicate standard errors. *, P < 0.05; ns, not significant. VC, vector control pSRKGm. All genes were cloned in pSRKGm.

Potential molecular mechanism of YE1324 regulating motility.

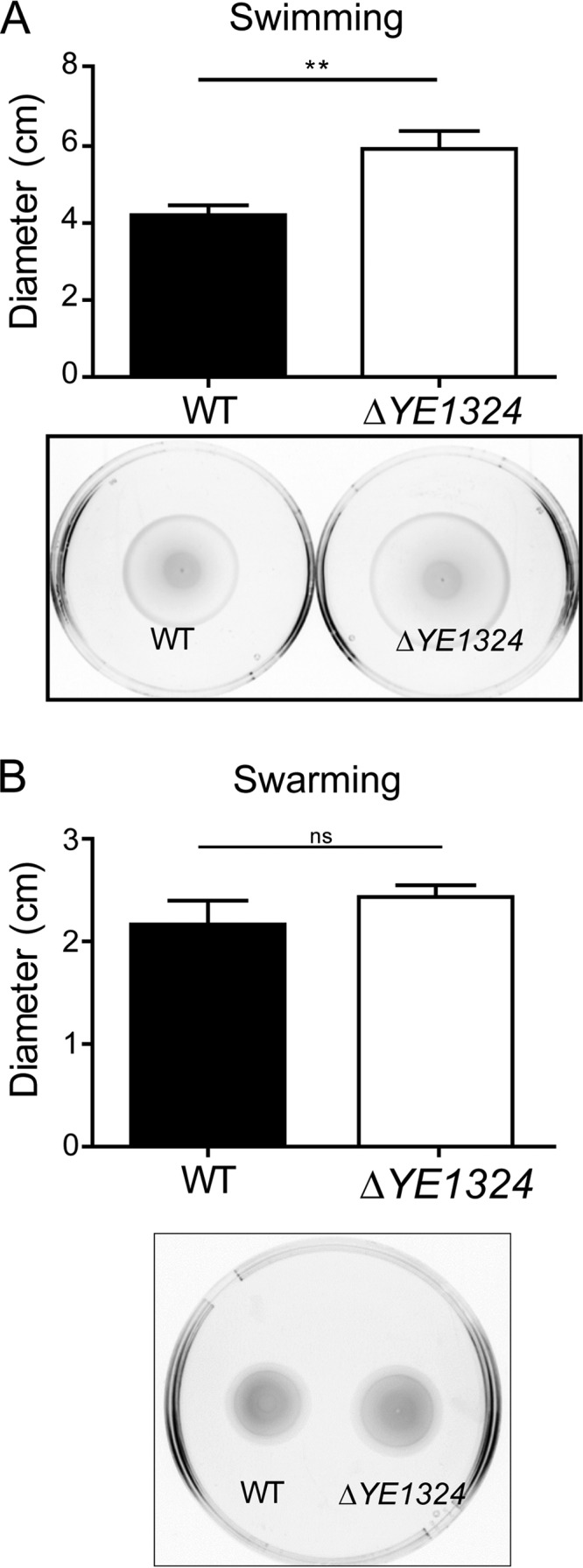

YE1324 downregulated motility in Y. enterocolitica when overexpressed, suggesting that YE1324 interacts with the Y. enterocolitica FlhDC (FlhDCYE). To verify the function of YE1324 on the chromosomal expression level, we constructed a YE1324 deletion. Indeed, the ΔYE1324 mutant showed enhanced swimming motility (Fig. 6A), and a trend for enhanced swarming motility (Fig. 6B) at 25°C.

FIG 6.

Effect of YE1324 on swimming and swarming motility in Y. enterocolitica. A YE1324 deletion led to a significant upregulation of swimming (A) and swarming (B) motility in Y. enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica 8081. Swimming motility was assessed in 0.2% TB0 agar. Single colonies were stabbed into the agar and plates were incubated at 25°C for 18 h. The swarming motility assay was performed on 0.3% TB0 Eiken agar supplemented with 10 mM glucose and incubated at 25°C for 20 h. Representative images of motility behavior are shown. Data are means from three independent experiments and bars indicate standard errors. **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

Since deletion of YE1324 relieves motility repression at 25°C, we wondered whether YE1324 and/or c-di-GMP signaling is involved in motility repression in Y. enterocolitica at 37°C. However, motility repression was not relieved in the ΔYE1324 mutant, even when the PDE YE2225 was overexpressed (data not shown).

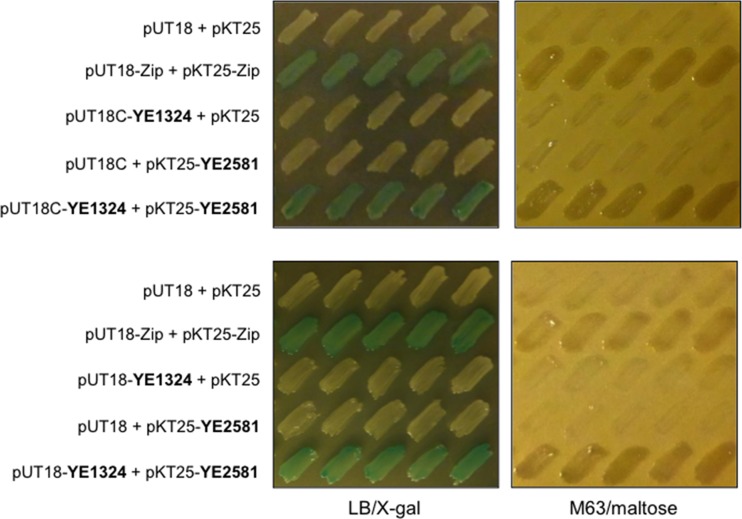

How does YE1324 affect motility? A reasonable hypothesis is that, similar to EAL-only proteins STM1344 and STM1697 in S. Typhimurium, YE1324 inhibits motility by interacting with FlhD to interfere with FlhDC functionality in Y. enterocolitica. To this end, we investigated whether YE1324 and FlhDYE could interact. We assessed protein-protein interactions by a bacterial two-hybrid system, an approach based on the restoration of adenylate cyclase activity upon the interaction of fusion proteins. Indeed, blue colonies due to cAMP-dependent β-galactosidase activity and the restoration of growth on maltose-supplemented minimal medium indicated that YE1324 and FlhDYE could interact with each other (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Assessment of protein-protein interaction between FlhDYE and YE1324 by bacterial two-hybrid assay. YE1324 could interact with FlhDYE (YE2581) from Y. enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica 8081. BTH101 reporter cells expressing the indicated proteins fused to the T18 or T25 domain of the Bordetella adenylate cyclase were patched on plates with X-Gal indicator and M63/maltose minimal medium. Blue colony color on the X-Gal plate and growth on the M63 medium plate indicate protein interaction. In pKT25 and pUT18C, the heterologous proteins are fused to the C-terminal ends of T25 and T18, respectively. In pUT18, the heterologous protein YE1324 is fused to the N-terminal end of T18. The two-hybrid experiment was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

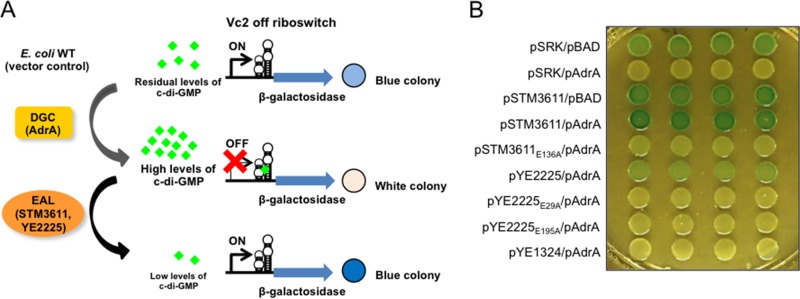

Assessment of phosphodiesterase activity by a riboswitch-based assay.

Although crystal structures for some EAL-only proteins are available (see Table S6), we observed that predicted catalytically active EAL-only proteins, but not EAL-only proteins without predicted catalytic activity, formed inclusion bodies upon overexpression (data not shown). Thus, we chose c-di-GMP riboswitch-controlled β-galactosidase activity as a readout to assess the catalytic function of EAL-only proteins (54). The Vc2 riboswitch is on at infinitesimal c-di-GMP levels and turns off upon the elevation of the c-di-GMP concentration. E. coli TOP10 with the Vc2 riboswitch on the chromosome exhibited already substantial β-galactosidase activity, indicating that c-di-GMP levels in these cells were too low to reliably assess PDE activity by enhanced β-galactosidase activity and accompanying colony color change (Fig. 8 and data not shown). Therefore, we expressed the diguanylate cyclase AdrA in E. coli TOP10::Vc2lacZY, and the β-galactosidase activity was repressed. Subsequent overexpression of the PDE STM3611 (YhjH) but not its active site mutant STM3611E136A relieved the repression, clearly demonstrating the PDE activity of STM3611. Similarly, expression of YE2225 but not its active site mutants YE2225E29A and YE2225E195A led to a decrease in c-di-GMP concentration and enhanced β-galactosidase activity. By contrast, YE1324 did not cause any color change, indicating a lack of PDE activity and further indicating that the role of YE1324 on motility might be primarily through its interaction with FlhD.

FIG 8.

Analysis of PDE activity of Y. enterocolitica proteins YE2225 and YE1324 using a chromosomally encoded Vc2-off riboswitch system. (A) Schematic model of the Vc2-off riboswitch system. The Vc2-off riboswitch system is composed of a riboswitch transcriptionally fused to lacZY. Upon c-di-GMP binding, the expression of the downstream gene is turned off. Thus, high levels of c-di-GMP result in repression of lacZY expression, while low levels of c-di-GMP result in lacZY derepression. In E. coli TOP10 cells (WT), there is a residual amount of c-di-GMP, resulting in a light blue colony. Expression of diguanylate cyclase, such as AdrA, results in a white colony, while expression of a PDE enhances color development (not informative in the E. coli TOP10 background). (B) β-Galactosidase reporter gene assays indicate PDE activity of YE2225 but not of YE2225 mutants YE2225E29A and YE2225E195A and YE1324. Expression of EAL genes in the pSRKGm vector was induced by 0.75 mM IPTG, while expression of the diguanylate cyclase AdrA in pBAD30 was induced by 0.003% l-arabinose. The cell-spotted plate also contained a X-Gal (80 μg/ml) and was incubated at 28°C for 1 to 2 days.

DISCUSSION

The c-di-GMP signaling network is to date the most complex secondary messenger signaling network in bacteria. Turnover of the c-di-GMP second messenger is performed by GGDEF domain diguanylate cyclases and EAL/HD-GYP domain PDEs, whereby the number of c-di-GMP turnover proteins encoded in a genome is generally correlated with genome size within the different bacterial classes or phyla (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Complete_Genomes/c-di-GMP.html [1]). So far, c-di-GMP turnover proteins have been subdivided according to their domain compositions (GGDEF, EAL, and GGDEF-EAL domain proteins), the nature of the N-terminal signaling domains (phosphotransfer receiver domain, small molecule sensing PAS or GAF domain, light sensing BLUF domain, and so on), and the conservation of the signature motifs (class I, II, and III EAL domains and active and inactive GGDEF domains with a conserved inhibitory I site). Here, we analyzed the properties of the stand-alone EAL domains, a distinct class of EAL domain proteins expressed in various bacterial phyla (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). In such proteins, there are no N-terminal domains that could potentially assist in dimerization and thus in enhancement of activity. Therefore, EAL-only proteins cannot fall into class II of Rao and colleagues (11) and must be either active PDEs (class I) or enzymatically inactive molecules (class III) that participate in regulation solely through protein-protein interactions. Given that FlhC and FlhD are only expressed in certain beta- and gammaproteobacteria (see, e.g., families PF05280 and PF05247 in the Pfam database), it is hardly surprising that most EAL-only domains found in phyla other than proteobacteria show remarkable conservation of the active site residues (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S2) and appear to be catalytically active PDEs, as has been demonstrated for three L. monocytogenes proteins (Fig. 1) (30). At the same time, the dimerization loop, which follows the conserved Asp151-Asp152 motif (cd01948 numbering) (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1) of strand 6, showed a clear conservation of three residues (Phe153, Gly/Ser154, and Gly156) but not the other three. It appears that the requirement for the DFG(A/S/T)(G/A)(Y/F)(S/A/T)(S/A/G/V/T) motif in this loop, advocated by Rao and colleagues (11), was unnecessarily restrictive. Examples of enzymatically active PDEs from L. monocytogenes and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Fig. 1) showed that these proteins can form catalytically active dimers despite having fairly divergent sequences in this loop and no assistance from any upstream domains (although interaction with independently encoded protein domains which affect activity cannot be excluded).

In phylogenetic trees, EAL-only proteins formed well-defined branches, separate from those of the EAL domain sequences coming from EAL-containing multidomain proteins of the same organisms (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S3 and S4). This suggests that (at least some) EAL-only domains represent an ancient protein lineage rather than a product of a recent domain fission. In general, EAL domain sequences clustered mostly according to their domain composition (Fig. S4), indicating that the formation of the principal domain architectures preceded the divergence of the key enterobacterial lineages. It also seems likely that the coexistence of domains within a conserved domain architecture restricts sequence diversification. These conclusions are consistent with the notion that the origin of c-di-GMP-mediated signaling occurred at an early stage of bacterial evolution (1, 55).

In S. Typhimurium, the EAL domain-only proteins STM1697, STM1344, and STM3611 are an integral part of the flagellar regulon cascade, primarily restricting flagellar expression and enhancing functionality. YE1324 of Y. enterocolitica (78, 79) is, despite c-di-GMP network reduction, also present in Yersinia pestis (56), which switches from a motile to nonmotile state upon infection. YE1324 seems to have an unconventional function similar to those of STM1697 and STM13244, as its deletion upregulated flagellum-mediated swimming and swarming motility. Also, the two-hybrid system assay indicated that YE1324 could interact with FlhD from Y. enterocolitica. Although YE1324 hardly affected motility in S. Typhimurium, a preliminary two-hybrid assay suggested it interacts with S. Typhimurium FlhD (data not shown). The interaction of YE1324 with the FlhD of S. Typhimurium (FlhDST) might not interfere with FlhDST functionality. Alternatively, this interaction with YE1324 could be weaker than in its native host, as the sequence of FlhDYE differs from that of FlhDST (data not shown). However, upregulation of the rdar biofilm formation does not exclude the possibility that YE1324 has another, yet unknown, binding partner in S. Typhimurium. As the amino acids mediating interactions with FlhD are not strictly conserved in YE1324 (Fig. 1), the molecular mechanisms behind this unconventional phenotype of YE1324 need to be investigated further. In general, noncanonical EAL-only proteins can have at least two protein-protein interaction interfaces: one that is interacting with FlhD (32, 35) and another one which targets FlhDC to the ClpXP protease (33).

The functionality of YE1324 in S. Typhimurium in the upregulation of rdar biofilm formation also indicates that these EAL-only proteins can readily acquire biological significance when horizontally transferred. Indeed, several of the EAL-only proteins of E. coli are encoded by plasmids (Fig. S4). Genes for an additional group of EAL-only proteins, including SfaII, are integral parts of operons harboring pilus biosynthesis genes, which are horizontally transferred into uropathogenic E. coli strains (37). However, of note, SfaII is only distantly related to STM3611, STM1344, and STM1697 (data not shown).

Surprisingly, nonmotile Shigella spp. have conserved functional YdiV and YhjH family homologs, although the flagellar regulon cascade does not seem to be intact or, as in S. flexneri 2a strain 24570T, is even missing a full-length FlhD protein, the target of the catalytically inactive EAL-only proteins of S. Typhimurium and E. coli. Thus, we hypothesize that motility is not the only physiological output of these proteins. The nonmotile whooping cough agent Bordetella pertussis still carries certain chemotaxis and flagellar genes, including flhD, which are negatively regulated by the EAL-only protein BvgR (20, 57). Although BvgR has a sequence quite distinct from that of STM1344/STM1697 (Fig. 1), it still could interact with B. pertussis FlhD (data not shown), which would explain some of its regulatory effects. In other species that do not possess the FlhDC regulon and/or are nonmotile, EAL domain-only proteins have diverged in sequence and function. The K. pneumoniae MrkJ PDE (identical to KPN_03274) degrades the c-di-GMP that is required for type 3 fimbria expression (29, 58). Finally, judging from the sequence of P. aeruginosa virulence regulator ToxR/RegA (18, 19) (Fig. 1), this protein cannot have PDE activity nor can it interact with FlhD, as FlhD is not encoded in P. aeruginosa. Such proteins must have alternative interaction partners that still remain uncharacterized. Some obvious candidates would be those containing the S helix, whose interaction with the enzymatically inactive EAL domain of the LapD protein has been characterized in detail (59). In summary, macro- as well as microevolution of the phylogenetically distinct EAL-only proteins extends beyond S. Typhimurium. FlhD is a common interaction partner, whereby catalytic activity and interaction with FlhD by EAL-only proteins seem to be mutually exclusive. However, EAL-only proteins are predicted to interact with an additional unknown protein(s). Thus, the diversity in function of the stand-alone EAL domain-only protein subfamily is only starting to be discovered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material, respectively. S. Typhimurium strain UMR1 (ATCC 14028 Nalr), Shigella flexneri 2a strain 24570T (ATCC 29903T), and Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae strain MGH 78578 (ATCC 700721) were either cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium with shaking at 200 rpm or grown on LB agar plates at 37°C supplemented with 100 μg · ml−1 ampicillin, 50 μg · ml−1 kanamycin, and 30 μg · ml−1 gentamicin, when required. Yersinia enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica strain 8081-L2 was cultivated in TB broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% NaCl) at 25°C with shaking at 200 rpm supplemented with 30 μg · ml−1 gentamicin, when required. The expression of genes cloned into pSRKGm was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside).

Sequence analysis.

The presence of EAL-only proteins in various taxa has been evaluated by searching the NCBI protein database for the EAL-containing proteins from 220 to 280 amino acid residues in length (the “EAL domain AND 220:280[SLEN]” search pattern) with additional filtering by taxonomy, such as, for example, “AND Aquificae[ORGN]” and limiting the source databases to GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ. Protein domain architectures were either taken from reference 24 or determined by comparing the sequences against the Pfam (39) and CDD/SPARCLE (60) databases. Sequence alignments of EAL domains for phylogenetic analysis were generated using MUSCLE (61) as implemented in MEGA7 (62). Highly divergent sequences were aligned by comparing them to the CDD profile cd01948 (60) with relaxed parameters. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using PhyML (63) with branch support values estimated using the aBayes algorithm (64). Graphical visualization and editing of the trees were performed in MEGA7 (62). The sequence logo was constructed using WebLogo (65).

Plasmid construction.

Seven genes of interest and that encoding STM3611 were amplified by PCR (primers are listed in Table S3) and cloned into the IPTG-inducible expression vector pSRKGm (66) with a 6×His tag at the C-terminal end. The PCR products and vectors were digested with NdeI and NheI, replacing lacZα of the plasmid with EAL genes. Site-directed mutants were obtained by assembly PCR and subsequent cloning into pSRKGm (primers listed in Table S3). The integrity of all sequences was confirmed by DNA sequencing on a StarSEQ platform. The constructs were transformed into E. coli, S. Typhimurium, and S. flexneri by electroporation (Bio-Rad); >100 ng of plasmid DNA was electroporated with one pulse of 1.3 kV for 7 ms in 1-mm cuvettes.

In the case of Y. enterocolitica, pSRKGm constructs were introduced by conjugation (67). Overnight cultures of Y. enterocolitica, E. coli with helper plasmid pRK2013, and E. coli TOP10 carrying the pSRKGm construct of interest were mixed in a 1:1:1 ratio. The mixture was spotted on LB agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. The bacteria were resuspended in 10 mM MgSO4 and plated on Yersinia-selective cefsulodin-Irgasan-novobiocin (CIN) agar (Oxoid, UK) containing 30 μg · ml−1 gentamicin. Positive clones were selected after an overnight incubation at 37°C.

Mutant construction.

Primers ye1324-f and ye1324-r were used to amplify a 409-bp internal fragment of the gene encoding YE1324 of Y. enterocolitica strain 8081. The primers introduced BamHI restriction sites for cloning into the suicide vector pSW23T (68) to obtain plasmid pSW23T-1324. The plasmid was then mobilized from E. coli strain ω7249::pSW23T-1324 into Y. enterocolitica strain 8081-L2, a restriction-negative derivative of strain 8081 (69). The resulting Cmr colonies were tested for the correct integration of pSW23T-1324 to obtain the 8081 ΔYE1324 mutant strain (8081 ΔYE1324::pSW23T-1324). PCR was performed using primers ye1324-f2 and ye1324-r2, which amplify a 701-bp fragment from the intact gene encoding YE1324 and a 2.8-kb fragment from the inactivated gene from 8081 ΔYE1324::pSW23T-1324.

Phenotypic evaluation. (i) Swimming motility.

For S. Typhimurium, the swimming motility test was performed in 0.3% LB agar plates supplemented with 30 μg · ml−1 gentamicin and 0.1 mM IPTG. Single colonies were inoculated into the agar and the motility diameter was measured after 5 h at 37°C. For Shigella strains, the motility test was performed in 4 ml of 0.18% LB agar added to a glass tube. A single colony was inoculated into the agar, and tubes were incubated for 72 h at 37°C (53). The motility of Y. enterocolitica was assessed in 0.2% TB0 (TB medium without salt [1% tryptone, 0.2% agar]) agar supplemented with 10 mM glucose. Single colonies were inoculated into the agar and incubated at 25°C and 37°C for 18 h (70). At least three independent experiments with three technical replicates were performed for all assays. To determine statistical significance, a two-sided Student t test was used.

(ii) Swarming motility.

The Y. enterocolitica swarming assay was performed on 0.3% TB0 Eiken agar supplemented with 10 mM glucose. Two microliters of an overnight culture was spotted on the plate and incubated at 25°C and 37°C for 20 h (70).

(iii) rdar morphotype assessment.

To assess the rdar morphotype formation, 5 μl of an overnight culture (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 4.0 to 5.0) was spotted onto an LB without salt agar plate supplemented with 40 μg · ml−1 Congo red and 20 μg · ml−1 Coomassie brilliant blue. Plates were incubated at 28°C for up to 72 h with phenotype assessment every 12 h.

Construction of a Vc2 riboswitch strain.

The Vc2 riboswitch along with lacZY were amplified from the recombinant pRS414 vector (gift from R. R. Breaker, Yale University). The PCR product and pGRG25 vector were digested with PacI and NotI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). Digested pGRG25 was dephosphorylated by Antarctic phosphatase (New England BioLabs) and then ligated with the digested PCR product by T4 DNA ligase (Roche Life Science). The resulting product was transformed into chemically competent E. coli TOP10 cells grown at 30°C. The transgene was inserted into the chromosomal Tn7 attachment site as described previously (71).

Vc2 riboswitch-based phosphodiesterase assessment assay.

The diguanylate cyclase AdrA gene cloned in pBAD30, EAL-only genes cloned into pSRKGm, and vector controls were cotransformed into E. coli TOP10 cells carrying the chromosomal Vc2 riboswitch-lacZY transcriptional fusion. Individual colonies were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking in LB medium. Next, 3 μl of culture grown to an OD600 of 0.6 was spotted onto an LB agar plate containing X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; 80 μg/ml), 0.75 mM IPTG, 0.003% l-arabinose (to induce the diguanylate cyclase, AdrA), and relevant antibiotics. β-Galactosidase activity as assessed by colony color development was observed at 28°C for up to 2 days.

Bacterial two-hybrid system analysis.

Full-length open reading frames of STM1925 (FlhDST) of S. Typhimurium and YE2581 (FlhDYE) and YE1324 from Y. enterocolitica subsp. enterocolitica 8081 were cloned into pKT25, pNKT25, pUT18, and pUT18C as N- and C-terminal fusion proteins. Genes of interest were PCR amplified, digested with XbaI and KpnI, and ligated into XbaI/KpnI-digested pKT25, pNKT25, pUT18, and pUT18C vectors. The sequence integrity of all constructs was checked by DNA sequencing. The oligonucleotides used are listed in Table S3. The resulting constructs express fusion proteins to the T25 and T18 domains of the adenylate cyclase encoded by cyaA from Bordetella pertussis. Protein-protein interactions were assayed through functional reconstitution of the adenylate cyclase activity in the cyaA-deficient E. coli strain BTH101, with activation of β-galactosidase activity and growth as the readouts (72). On LB agar plates at 30°C supplemented with 40 μg · ml−1 of the substrate X-Gal and 0.5 mM IPTG, the cleavage of the substrate X-Gal resulted in a blue colony phenotype observed for up to 72 h. Growth promotion was assessed on M63 minimal medium agar at 28°C containing 0.5 mM IPTG and 0.2% (wt/vol) maltose as the sole carbon source for up to 72 h.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge technical assistance of Juha Laitinen and thank Yuri Wolf (NCBI) for advice on phylogenetic analysis. We thank Ronald R. Breaker, who provided the pRS414::Vc2 riboswitch construct.

Youssef El Mouali received a scholarship from Eurolife (JPTEM program). This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Natural Sciences and Engineering (grant 621-2013-4809) and the Karolinska Institutet. M.Y.G. is supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program at the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00179-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Römling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamayo R, Pratt JT, Camilli A. 2007. Roles of cyclic diguanylate in the regulation of bacterial pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol 61:131–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schirmer T, Jenal U. 2009. Structural and mechanistic determinants of c-di-GMP signalling. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galperin MY, Nikolskaya AN, Koonin EV. 2001. Novel domains of the prokaryotic two-component signal transduction systems. FEMS Microbiol Lett 203:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou SH, Galperin MY. 2016. Diversity of cyclic di-GMP-binding proteins and mechanisms. J Bacteriol 198:32–46. doi: 10.1128/JB.00333-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barends TR, Hartmann E, Griese JJ, Beitlich T, Kirienko NV, Ryjenkov DA, Reinstein J, Shoeman RL, Gomelsky M, Schlichting I. 2009. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial light-regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Nature 459:1015–1018. doi: 10.1038/nature07966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tchigvintsev A, Xu X, Singer A, Chang C, Brown G, Proudfoot M, Cui H, Flick R, Anderson WF, Joachimiak A, Galperin MY, Savchenko A, Yakunin AF. 2010. Structural insight into the mechanism of c-di-GMP hydrolysis by EAL domain phosphodiesterases. J Mol Biol 402:524–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao F, Yang Y, Qi Y, Liang ZX. 2008. Catalytic mechanism of cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase: a study of the EAL domain-containing RocR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 190:3622–3631. doi: 10.1128/JB.00165-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simm R, Remminghorst U, Ahmad I, Zakikhany K, Römling U. 2009. A role for the EAL-like protein STM1344 in regulation of CsgD expression and motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 191:3928–3937. doi: 10.1128/JB.00290-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad I, Wigren E, Le Guyon S, Vekkeli S, Blanka A, El Mouali Y, Anwar N, Chuah ML, Lunsdorf H, Frank R, Rhen M, Liang ZX, Lindqvist Y, Römling U. 2013. The EAL-like protein STM1697 regulates virulence phenotypes, motility and biofilm formation in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 90:1216–1232. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao F, Qi Y, Chong HS, Kotaka M, Li B, Li J, Lescar J, Tang K, Liang ZX. 2009. The functional role of a conserved loop in EAL domain-based cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase. J Bacteriol 191:4722–4731. doi: 10.1128/JB.00327-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Römling U. 2009. Rationalizing the evolution of EAL domain-based cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterases. J Bacteriol 191:4697–4700. doi: 10.1128/JB.00651-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzzo CR, Dunger G, Salinas RK, Farah CS. 2013. Structure of the PilZ-FimXEAL-c-di-GMP complex responsible for the regulation of bacterial type IV pilus biogenesis. J Mol Biol 425:2174–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newell PD, Monds RD, O'Toole GA. 2009. LapD is a bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP-binding protein that regulates surface attachment by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:3461–3466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808933106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundriyal A, Massa C, Samoray D, Zehender F, Sharpe T, Jenal U, Schirmer T. 2014. Inherent regulation of EAL domain-catalyzed hydrolysis of second messenger cyclic di-GMP. J Biol Chem 289:6978–6990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.516195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellini D, Horrell S, Hutchin A, Phippen CW, Strange RW, Cai Y, Wagner A, Webb JS, Tews I, Walsh MA. 2017. Dimerisation induced formation of the active site and the identification of three metal sites in EAL-phosphodiesterases. Sci Rep 7:42166. doi: 10.1038/srep42166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown NL, Misra TK, Winnie JN, Schmidt A, Seiff M, Silver S. 1986. The nucleotide sequence of the mercuric resistance operons of plasmid R100 and transposon Tn501: further evidence for mer genes which enhance the activity of the mercuric ion detoxification system. Mol Gen Genet 202:143–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00330531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wozniak DJ, Cram DC, Daniels CJ, Galloway DR. 1987. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of toxR: a gene involved in exotoxin A regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res 15:2123–2135. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank DW, Storey DG, Hindahl MS, Iglewski BH. 1989. Differential regulation by iron of regA and toxA transcript accumulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 171:5304–5313. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5304-5313.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merkel TJ, Barros C, Stibitz S. 1998. Characterization of the bvgR locus of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol 180:1682–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tal R, Wong HC, Calhoon R, Gelfand D, Fear AL, Volman G, Mayer R, Ross P, Amikam D, Weinhouse H, Cohen A, Sapir S, Ohana P, Benziman M. 1998. Three cdg operons control cellular turnover of cyclic di-GMP in Acetobacter xylinum: genetic organization and occurrence of conserved domains in isoenzymes. J Bacteriol 180:4416–4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulasakara H, Lee V, Brencic A, Liberati N, Urbach J, Miyata S, Lee DG, Neely AN, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Ausubel FM, Lory S. 2006. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:2839–2844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511090103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueda A, Wood TK. 2010. Tyrosine phosphatase TpbA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls extracellular DNA via cyclic diguanylic acid concentrations. Environ Microbiol Rep 2:449–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hengge R, Galperin MY, Ghigo JM, Gomelsky M, Green J, Hughes KT, Jenal U, Landini P. 2015. Systematic nomenclature for GGDEF and EAL domain-containing c-di-GMP turnover proteins of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 198:7–11. doi: 10.1128/JB.00424-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko M, Park C. 2000. Two novel flagellar components and H-NS are involved in the motor function of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 303:371–382. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pesavento C, Becker G, Sommerfeldt N, Possling A, Tschowri N, Mehlis A, Hengge R. 2008. Inverse regulatory coordination of motility and curli-mediated adhesion in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev 22:2434–2446. doi: 10.1101/gad.475808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahman M, Simm R, Kader A, Basseres E, Römling U, Mollby R. 2007. The role of c-di-GMP signaling in an Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria strain. FEMS Microbiol Lett 273:172–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi X, Yamazaki A, Biddle E, Zeng Q, Yang CH. 2010. Genetic analysis of two phosphodiesterases reveals cyclic diguanylate regulation of virulence factors in Dickeya dadantii. Mol Microbiol 77:787–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JG, Clegg S. 2010. Role of MrkJ, a phosphodiesterase, in type 3 fimbrial expression and biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol 192:3944–3950. doi: 10.1128/JB.00304-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen LH, Koseoglu VK, Guvener ZT, Myers-Morales T, Reed JM, D'Orazio SE, Miller KW, Gomelsky M. 2014. Cyclic di-GMP-dependent signaling pathways in the pathogenic firmicute Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004301. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hisert KB, MacCoss M, Shiloh MU, Darwin KH, Singh S, Jones RA, Ehrt S, Zhang Z, Gaffney BL, Gandotra S, Holden DW, Murray D, Nathan C. 2005. A glutamate-alanine-leucine (EAL) domain protein of Salmonella controls bacterial survival in mice, antioxidant defence and killing of macrophages: role of cyclic diGMP. Mol Microbiol 56:1234–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spurbeck RR, Alteri CJ, Himpsl SD, Mobley HL. 2013. The multifunctional protein YdiV represses P fimbria-mediated adherence in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 195:3156–3164. doi: 10.1128/JB.02254-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takaya A, Erhardt M, Karata K, Winterberg K, Yamamoto T, Hughes KT. 2012. YdiV: a dual function protein that targets FlhDC for ClpXP-dependent degradation by promoting release of DNA-bound FlhDC complex. Mol Microbiol 83:1268–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wada T, Morizane T, Abo T, Tominaga A, Inoue-Tanaka K, Kutsukake K. 2011. EAL domain protein YdiV acts as an anti-FlhD4C2 factor responsible for nutritional control of the flagellar regulon in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 193:1600–1611. doi: 10.1128/JB.01494-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li B, Li N, Wang F, Guo L, Huang Y, Liu X, Wei T, Zhu D, Liu C, Pan H, Xu S, Wang HW, Gu L. 2012. Structural insight of a concentration-dependent mechanism by which YdiV inhibits Escherichia coli flagellum biogenesis and motility. Nucleic Acids Res 40:11073–11085. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart MK, Cummings LA, Johnson ML, Berezow AB, Cookson BT. 2011. Regulation of phenotypic heterogeneity permits Salmonella evasion of the host caspase-1 inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:20742–20747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108963108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sjöström AE, Sonden B, Muller C, Rydstrom A, Dobrindt U, Wai SN, Uhlin BE. 2009. Analysis of the sfaXII locus in the Escherichia coli meningitis isolate IHE3034 reveals two novel regulatory genes within the promoter-distal region of the main S fimbrial operon. Microb Pathog 46:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Povolotsky TL, Hengge R. 2015. Genome-based comparison of cyclic di-GMP signaling in pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli strains. J Bacteriol 198:111–126. doi: 10.1128/JB.00520-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, Salazar GA, Tate J, Bateman A. 2016. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The UniProt Consortium. 2015. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D204–D212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geer LY, Domrachev M, Lipman DJ, Bryant SH. 2002. CDART: protein homology by domain architecture. Genome Res 12:1619–1623. doi: 10.1101/gr.278202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarvik T, Smillie C, Groisman EA, Ochman H. 2010. Short-term signatures of evolutionary change in the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 14028 genome. J Bacteriol 192:560–567. doi: 10.1128/JB.01233-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grantcharova N, Peters V, Monteiro C, Zakikhany K, Römling U. 2010. Bistable expression of CsgD in biofilm development of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 192:456–466. doi: 10.1128/JB.01826-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamprokostopoulou A, Monteiro C, Rhen M, Römling U. 2010. Cyclic di-GMP signalling controls virulence properties of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium at the mucosal lining. Environ Microbiol 12:40–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Guyon S, Simm R, Rehn M, Römling U. 2015. Dissecting the cyclic di-guanylate monophosphate signalling network regulating motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Environ Microbiol 17:1310–1320. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Römling U. 2005. Characterization of the rdar morphotype, a multicellular behaviour in Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Mol Life Sci 62:1234–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4557-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowles KN, Willis DK, Engel TN, Jones JB, Barak JD. 2015. Diguanylate cyclases AdrA and STM1987 regulate Salmonella enterica exopolysaccharide production during plant colonization in an environment-dependent manner. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:1237–1248. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03475-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin Q, Yuan Z, Xu J, Wang Y, Shen Y, Lu W, Wang J, Liu H, Yang J, Yang F, Zhang X, Zhang J, Yang G, Wu H, Qu D, Dong J, Sun L, Xue Y, Zhao A, Gao Y, Zhu J, Kan B, Ding K, Chen S, Cheng H, Yao Z, He B, Chen R, Ma D, Qiang B, Wen Y, Hou Y, Yu J. 2002. Genome sequence of Shigella flexneri 2a: insights into pathogenicity through comparison with genomes of Escherichia coli K-12 and O157. Nucleic Acids Res 30:4432–4441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomson NR, Howard S, Wren BW, Holden MT, Crossman L, Challis GL, Churcher C, Mungall K, Brooks K, Chillingworth T, Feltwell T, Abdellah Z, Hauser H, Jagels K, Maddison M, Moule S, Sanders M, Whitehead S, Quail MA, Dougan G, Parkhill J, Prentice MB. 2006. The complete genome sequence and comparative genome analysis of the high pathogenicity Yersinia enterocolitica strain 8081. PLoS Genet 2:e206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simm R, Lusch A, Kader A, Andersson M, Romling U. 2007. Role of EAL-containing proteins in multicellular behavior of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 189:3613–3623. doi: 10.1128/JB.01719-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tominaga A, Mahmoud MA, Mukaihara T, Enomoto M. 1994. Molecular characterization of intact, but cryptic, flagellin genes in the genus Shigella. Mol Microbiol 12:277–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tominaga A, Lan R, Reeves PR. 2005. Evolutionary changes of the flhDC flagellar master operon in Shigella strains. J Bacteriol 187:4295–4302. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.4295-4302.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giron JA. 1995. Expression of flagella and motility by Shigella. Mol Microbiol 18:63–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18010063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sudarsan N, Lee ER, Weinberg Z, Moy RH, Kim JN, Link KH, Breaker RR. 2008. Riboswitches in eubacteria sense the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Science 321:411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1159519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J Bacteriol 187:1792–1798. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1792-1798.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bobrov AG, Kirillina O, Ryjenkov DA, Waters CM, Price PA, Fetherston JD, Mack D, Goldman WE, Gomelsky M, Perry RD. 2011. Systematic analysis of cyclic di-GMP signalling enzymes and their role in biofilm formation and virulence in Yersinia pestis. Mol Microbiol 79:533–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coutte L, Huot L, Antoine R, Slupek S, Merkel TJ, Chen Q, Stibitz S, Hot D, Locht C. 2016. The multifaceted RisA regulon of Bordetella pertussis. Sci Rep 6:32774. doi: 10.1038/srep32774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilksch JJ, Yang J, Clements A, Gabbe JL, Short KR, Cao H, Cavaliere R, James CE, Whitchurch CB, Schembri MA, Chuah ML, Liang ZX, Wijburg OL, Jenney AW, Lithgow T, Strugnell RA. 2011. MrkH, a novel c-di-GMP-dependent transcriptional activator, controls Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm formation by regulating type 3 fimbriae expression. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002204. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Navarro MV, Newell PD, Krasteva PV, Chatterjee D, Madden DR, O'Toole GA, Sondermann H. 2011. Structural basis for c-di-GMP-mediated inside-out signaling controlling periplasmic proteolysis. PLoS Biol 9:e1000588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, He J, Lanczycki CJ, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lu F, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Wang Z, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zheng C, Geer LY, Bryant SH. 2017. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D200–D203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anisimova M, Gil M, Dufayard JF, Dessimoz C, Gascuel O. 2011. Survey of branch support methods demonstrates accuracy, power, and robustness of fast likelihood-based approximation schemes. Syst Biol 60:685–699. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syr041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. 2004. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khan SR, Gaines J, Roop RM II, Farrand SK. 2008. Broad-host-range expression vectors with tightly regulated promoters and their use to examine the influence of TraR and TraM expression on Ti plasmid quorum sensing. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:5053–5062. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01098-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Biedzka-Sarek M, Venho R, Skurnik M. 2005. Role of YadA, Ail, and lipopolysaccharide in serum resistance of Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3. Infect Immun 73:2232–2244. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2232-2244.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Demarre G, Guerout AM, Matsumoto-Mashimo C, Rowe-Magnus DA, Marliere P, Mazel D. 2005. A new family of mobilizable suicide plasmids based on broad host range R388 plasmid (IncW) and RP4 plasmid (IncPalpha) conjugative machineries and their cognate Escherichia coli host strains. Res Microbiol 156:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang L, Radziejewska-Lebrecht J, Krajewska-Pietrasik D, Toivanen P, Skurnik M. 1997. Molecular and chemical characterization of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen and its role in the virulence of Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:8. Mol Microbiol 23:63–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1871558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsai CS, Winans SC. 2011. The quorum-hindered transcription factor YenR of Yersinia enterocolitica inhibits pheromone production and promotes motility via a small non-coding RNA. Mol Microbiol 80:556–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McKenzie GJ, Craig NL. 2006. Fast, easy and efficient: site-specific insertion of transgenes into enterobacterial chromosomes using Tn7 without need for selection of the insertion event. BMC Microbiol 6:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Karimova G, Pidoux J, Ullmann A, Ladant D. 1998. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:5752–5756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gupta K, Kumar P, Chatterji D. 2010. Identification, activity and disulfide connectivity of c-di-GMP regulating proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 5:e15072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Flores-Valdez MA, Aceves-Sanchez Mde J, Pedroza-Roldan C, Vega-Dominguez PJ, Prado-Montes de Oca E, Bravo-Madrigal J, Laval F, Daffe M, Koestler B, Waters CM. 2015. The cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase gene Rv1357c/BCG1419c affects BCG pellicle production and in vivo maintenance. IUBMB Life 67:129–138. doi: 10.1002/iub.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brown R, Marchesi JR, Morby AP. 2011. Functional characterisation of Lp_2714, an EAL-domain protein from Lactobacillus plantarum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 411:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tan H, West JA, Ramsay JP, Monson RE, Griffin JL, Toth IK, Salmond GP. 2014. Comprehensive overexpression analysis of cyclic-di-GMP signalling proteins in the phytopathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum reveals diverse effects on motility and virulence phenotypes. Microbiology 160:1427–1439. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.076828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang KC, Hsu YH, Huang YN, Yeh KS. 2012. A previously uncharacterized gene stm0551 plays a repressive role in the regulation of type 1 fimbriae in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. BMC Microbiol 12:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Young GM, Miller VL. 1997. Identification of novel chromosomal loci affecting Yersinia enterocolitica pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol 25:319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heermann R, Fuchs TM. 2008. Comparative analysis of the Photorhabdus luminescens and the Yersinia enterocolitica genomes: uncovering candidate genes involved in insect pathogenicity. BMC Genomics 9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.