Abstract

Alopecia areata is an autoimmune disorder characterized by transient, non-scarring hair loss and preservation of the hair follicle. Hair loss can take many forms ranging from loss in well-defined patches to diffuse or total hair loss, which can affect all hair bearing sites. Patchy alopecia affecting the scalp is the most common type. Alopecia areata affects nearly 2% of the general population at some point during their lifetime. Skin biopsies of alopecia areata affected skin show a lymphocytic infiltrate in and around the bulb or the lower part of the hair follicle in anagen (hair growth) phase. A breakdown of immune privilege of the hair follicle is thought to be an important driver of alopecia areata. Genetic studies in patients and mouse models showed that alopecia areata is a complex, polygenic disease. Several genetic susceptibility loci were identified associated with signaling pathways that are important to hair follicle cycling and development. Alopecia areata is usually diagnosed based on clinical manifestations, but dermoscopy and histopathology can be helpful. Alopecia areata is difficult to manage medically, but recent advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms have revealed new treatments and the possibility of remission in the near future.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common type of hair loss or alopecia in humans; it is an autoimmune disease with a variable, typically relapsing or remitting, course that can be persistent – especially when hair loss is extensive. Alopecia areata is the second-most frequent non-scarring alopecia, after male and female pattern alopecia (Box 1). Clinical patterns of hair loss in alopecia areata are usually very distinct. The most common pattern is a small annular or patchy bald lesion (patchy alopecia areata), usually on the scalp, that can progress to total loss of scalp hair only (alopecia totalis), and total loss of all body hair (alopecia universalis) (Box 2).

Box 1. Primary hair loss disorders204.

Non-scarring alopecias

Non-scarring types of alopecia (also known as non-cicatricial alopecias) refer to hair loss due to changes in hair cycle, hair follicle size, hair breakage or a combination of these, with preservation of the hair follicle.

Male pattern hair loss (also known as androgenic alopecia): alopecia characterized by a receding hairline and diffuse hair loss at the crown that affects 50% of men by age 50 and is genetically determined (polygenic) and androgen-dependent.

Female pattern hair loss: common and similar to male pattern hair loss but characterized by diffuse hair loss with preservation of frontal hair line and less well defined etiology.

Telogen effluvium: excessive hair shedding, which presents either as an acute self-limiting form triggered by diverse events (for example, childbirth, febrile illness, major surgery and rapid weight loss) or as a chronic type, associated with female pattern hair loss.

Trichotillomania: hair-pulling impulse control disorder that is characterized by irregular patches or tonsural pattern of hair loss with broken hairs that are firmly attached in the scalp.

Traction alopecia: hair loss due to chronic mechanical traction from hair styling, which is reversible in early stages but might become irreversible due to follicular deletion owing to sustained traction.

Tinea capitis: a curable disease caused by fungal infection presenting in children and is characterized by patchy hair loss with signs of scalp inflammation (such as erythema and scaling of the scalp, and hair shaft infection and presence of fungi observed in pulled hair).

Short anagen syndrome: usually presents in childhood and is characterized by a normal density and hair strength, but minimal hair growth.

Loose anagen syndrome: usually presents in childhood and occasionally in adults and is characterized by slightly thinned, unruly, non-growing hair.

Temporal alopecia triangularis: a disorder that presents in newborn or young children and is characterized by a triangular or lancet-shaped bald spot with normal hair numbers, but very few terminal hairs (most are vellus hairs).

Scarring alopecias

Scarring types of alopecia (also known as cicatritial alopecias) refer to forms of hair loss in which hair follicles are destroyed owing to inflammation, or rarely, malignancy (such as cutaneous lymphoma). Affected skin shows loss of follicular ostia (the openings of the hair follicle though which the hair fiber emerges through the skin), but the early stages might resemble alopecia areata.

Lichen planopilaris: a chronic inflammatory disease that causes permanent hair follicle destruction typically characterized by patchy hair loss on the scalp with discrete follicular erythema at the margins of bald patches and sometimes associated with cutaneous and/or mucosal lichen planus (that is, non-infectious itchy rash).

Frontal fibrosing alopecia: type of lichen planopilaris, but with a different pattern of hair loss (in the frontal and frontotemporal hair line and eye brows), typically affecting postmenopausal women.

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a subtype of lupus erythematosus that presents with a symptomatic patch that evolves into scaly, indurated papules and gradually forms ill-defined, irregular or round plaques with variable atrophy, follicular plugging, telangiectasia and depigmentation.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a condition mainly seen in women of African ethnicity characterized by patchy scarring lesions starting at posterior crown or vertex and extending in a centrifugal pattern along the scalp; the etiology involves genetic and environmental factors, such as African-American hair styling techniques.

Folliculitis decalvans: inflammation of the hair follicle involving neutrophils and lymphocytes possibly as a reaction to Staphylococcus aureus colonization characterized by patchy scarring hair loss with pustular lesions at the margins and mainly affects men.

Genetic hair disorders

Many syndromic and non-syndromic types of hair loss are due to single gene mutations. The mutations can affect follicular development, normal hair cycling and hair fiber fragility; most conditions are present from infancy or childhood.

Box 2. Types of alopecia areata.

Patchy alopecia areata: one, multiple separate or conjoined (reticular) patches of hair loss.

Alopecia totalis: total or near-total loss of hair on the scalp.

Alopecia universalis: total to near-total loss of hair on all haired surfaces of the body.

Alopecia incognita: diffuse total hair loss with positive pull test, yellow dots, short, miniaturized regrowing hairs, but without nail involvement.

Ophiasis: hair loss in a band-like shape along the circumference of the head, more specifically along the border of the temporal and occipital bones.

Sisaipho: extensive alopecia except around the periphery of the scalp.

Marie Antoinette syndrome (also called canities subita): acute episode of diffuse alopecia with very sudden “overnight” greying with preferential loss of pigmented hair205.

Historically, numerous hypotheses on the cause (or causes) of alopecia areata have been proposed, such as infection, a trophoneurotic hypothesis (based on the association between the time of onset alopecia areata with emotional or physical stress and/or trauma), thallium acetate poisoning (owing to a similar clinical presentation), thyroid disease and hormonal fluctuations (for example, in pregnancy or menopause). Inflammation of the hair follicles in alopecia areata mediated by leukocytes was described over a century ago yet the involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata has only been recognized as the primary underlying cause since the late 1950s, when several immune related and several key pathogenetic effector cells were identified 1,2.

The generation of a National Alopecia Areata Registry3 in the United States in 2000 provided access to data from >10,000 patients. The registry enabled the application of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that have identified candidate genes associated with susceptibility to alopecia areata4, as well as an evaluation of important epidemiological and socio-medical issues, such as quality of life (QOL)5. Concurrently, rodent models6–8 that faithfully recapitulate the disease in humans and have enabled functional studies have been identified, and quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping (a technique that links variations in DNA to phenotype)9, 10 has been performed. Together, all these techniques and associated observations have now firmly established that alopecia areata is a complex, polygenic, immune-mediated disease that can now be interrogated to identify biomarkers to differentiate its severity or subtypes9.

In this Primer, we describe the current knowledge on the epidemiology of alopecia areata from a global perspective, the underlying pathophysiology, and genetic basis of this complex disease, concurrent diseases, diagnostic approaches, differential diagnoses, and current treatment approaches, as well as new breakthroughs.

Epidemiology

A high degree of phenotypic and genotypic variability observed in AA, which is complex genetic disease determined by genetic and environmental factors. The reported prevalance, age of onset, and history and concurrent diseases vary widely. Studies performed in a small number of patients should be viewed with caution.

Incidence and prevalence

Alopecia areata affects approximately 2% of the general population at some point during their lifetime, as documented by several large epidemiological studies from Europe10, North America11, and Asia12,13 The prevalence of alopecia areata in the early 1970s was reported to be between 0.1% to 0.2% with a life time incidence of 1.7%14. One study in Olmsted County (Minnesota, USA) based on data collated between 1975–1989 from patients with alopecia areata who were seen by a dermatologist showed that overall incidence was 20.2 per 100,000 person-years, did not change with time, and had no sexual dichotomy15. A follow-up study of this population form 1990–2009 found that the cumulative incidence increased almost linearly with age and that the lifetime incidence of alopecia areata was 2.1%16.

Although it is generally considered that there is no sexual dichotomy15,17, some studies show that the prevalence seems to shift to women in patients >45 years of age18–20. This skewed incidence might be an artifact since women might seek medical attention as they age more than men. Indeed, other population surveys suggest that alopecia areata is slightly more common in men20. One study found that men were more likely to be diagnosed at an earlier age than women19. No studies have determined if alopecia areata prevalence is different between ethnic groups21. Most studies report no significant differences in the age of onset, duration, or type of alopecia areata by sex or ethnicity17.

The onset of alopecia areata might be at any age; however, most patients develop the condition before the age of 40 years with the with a mean age of onset between 25 and 36 years17. Early-onset alopecia areata (mean age of onset between ages 5–10 years) predominantly presents as a more severe subtype, such as alopecia universalis17,22–25 (Box 2).

Genetic factors

Several lines of evidence support the notion that alopecia areata has a genetic basis. In general, the prevalence of adult patients with a family history is estimated to be between 0% and 8.6%26,27, whereas in children data between 10% and 51.6% are reported22–24,28. One study found that men were more likely to have a positive family history than women19. The occurrence of the disease in identical twins29–34, siblings35 and families with several generations of affected individuals36–38 indicates that this alopecia areata has a heritable basis. Most of the early human genetic studies were candidate gene association studies, in which linkage to specific genes or groups of genes was the focus. These studies focused on the human leukocyte antigen class II (HLA-D) region on human chromosome 6 as the most likely region for genes that regulate susceptibility or resistance to alopecia areata39. Family-based linkage studies and GWAS analyses, which were greatly enabled by the repository of the National Alopecia Areata Registry3, identified linkage or association on many chromosomes, which suggests that alopecia areata is a very complex polygenic disease4,40. These results confirmed earlier QTL analysis studies using an alopecia areata mouse model, often with similar, if not identical results41,42.

Concurrent Diseases

Alopecia areata is associated with several concurrent diseases (comorbidities) including depression, anxiety, and several autoimmune diseases including thyroid disease (hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, goiter ant thyroiditis), lupus erythematosus, vitiligo, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease17,43. The frequency of these concurrent diseases varies between geographically separate populations, which may suggest genetic variability within these different populations. A retrospective study in Taiwan found that patients with alopecia areata had higher hazard ratios for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and psoriasis within the 3-year follow-up period than healthy controls44. In addition, increased prevalence of other forms of inflammatory skin disease such as atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, psoriasis and lichen planus were found than in controls, suggesting that patients with alopecia areata are at increased risk of developing variety of T-cell driven inflammatory skin diseases45. Severe alopecia areata might be accompanied by nail changes20. Atopic diseases, such as sinusitis, asthma, rhinitis, and especially atopic dermatitis, are also more common than expected in populations with alopecia areata43, and are associated with early-onset and more severe forms of hair loss. In a Korean population, atopic dermatitis was significantly more common in patients with early-onset alopecia areata, whereas thyroid disease was the most common in late-onset disease46; findings were similar in Sri Lanka20. In a review of 17 studies, investigators found higher odds of atopic dermatitis in patients with alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis compared to those with patchy alopecia areata47. In a large-scale epidemiological study in Taiwan investigators found a correlation between prior herpes zoster outbreaks with alopecia exposure within 3 years, suggesting that stress might trigger alopecia areata48. Several studies, with and without controls, demonstrated a high prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity associated with alopecia areata49, whereas others found lower frequencies than in earlier studies, indicating that there is no need for detailed investigations into these diseases without a clinical history to suggest they are present50.

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

Genetics

Studies aimed at elucidating the complex genetics of alopecia areata have been undertaken by a number of groups using techniques ranging from candidate-gene association studies to transcriptional profiling of affected skin to large GWAS. The initial genetic studies concentrated on single genes that were known to be involved in related autoimmune diseases. Interestingly, many of these genes did in fact play a role in alopecia areata in addition to inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, psoriasis, and type 1 diabetes mellitus51. Owing to the focus on an autoimmune etiology, the HLA region, which encodes MHC molecules in humans, was initially identified as a major contributor to the alopecia areata phenotype51–54. The HLA region is one of the most gene-dense regions of the genome and encodes for key immune regulators55. Recent GWAS meta-analyses have localized the HLA signal largely to the HLA-DRB1 region.

Subsequent large-scale genetic studies have added to the list of genes associated with alopecia areata and further validated the role of the HLA region genes. For example, the several GWAS analysis in humans have identified 14 genetic loci associated with alopecia areata, many of which are known to be involved in immune function4,53,56. One locus, in particular, harboring the genes encoding the natural killer (NK) cell receptor D (NKG2D; encoded by KLRK1) ligands NKG2DL3 (encoded by ULBP3) and retinoic acid early transcript 1L protein (encoded by RAET1L; also known as ULBP6), was uniquely implicated in AA and not in other autoimmune diseases, which suggests a key role in pathogenesis. Indeed, this has been borne out of functional studies showing that CD8+NKG2D+T cells are the major effectors of AA disease pathogenesis. The dependency of these cells on IL15 signaling for their survival provided a rationale for using Janus Kinase (JAK) inhibitors to target the downstream effectors of this pathway in developing new therapeutic approaches.

In addition, gene expression studies have been used to validate these genetic studies and to assess local gene expression changes in affected areas. These studies have also identified more genes whose expressions are changed during disease progression41,42,57,58. Gene expression profiling studies have revealed predominant signatures of the Interferon gamma pathway and its related cytokines, as well as a predominant signature for cytotoxic T cells, both of which are mediated by JAK kinases as their downstream effectors. The emergence of these signatures further refined the focus using small-molecule JAK inhibitors. Recently, associations between alopecia areata and copy number variations (CNV) were found using genome-wide scans (Box 3)59.

Box 3. Genes involved in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata.

| Human Gene | Human Chr. | Mouse Gene | Mouse Chr. |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS | |||

| ACOXL | 2 | Acoxl | 2 |

| ATXN2 | 12 | Atxn2 | 5 |

| BCL2L11(BIM) | 2 | Bcl2l11 | 2 |

| BTNL2 | 6 | Btnl2 | 17 |

| C6orf10 | 6 | BC051142 | 17 |

| CD28 | 2 | Cd28 | 1 |

| CIITA | 16 | Ciita | 16 |

| CLEC16A (KIAA0350) | 16 | Clec16a | 16 |

| CTLA4 | 2 | Ctla4 | 1 |

| EMSY (C11orf30) | 11 | Emsy | 7 |

| ERBB3 | 12 | Erbb3 | 10 |

| ICOS | 2 | Icos | 1 |

| IKZF4 | 12 | Ikzf4 | 10 |

| IL13 | 5 | Il13 | 11 |

| IL15RA | 10 | Il15ra | 2 |

| IL2 | 4 | Il2 | 3 |

| IL21 | 4 | Il21 | 3 |

| IL2RA | 10 | Il2ra | 2 |

| IL4 | 5 | Il4 | 11 |

| LRRC32 (GARP) | 11 | Lrrc32 | 7 |

| MICA | 6 | 1300017J02Rik | 9 |

| NOTCH4 | 6 | Notch4 | 17 |

| NR4A3 | 9 | Nr4a3 | 4 |

| PRDX5 | 11 | Prdx5 | 19 |

| PTPN22 | 1 | Ptpn22 | 3 |

| RAET1L (ULBP6) | 6 | N/A | N/A |

| SH2B3 (LNK) | 12 | Sh2b3 | 5 |

| SOCS1 | 16 | Socs1 | 16 |

| SPATA5 | 4 | Spata5 | 3 |

| STX17 | 9 | Stx4 | 4 |

| ULBP3 | 6 | 9230019H11Rik | 10 |

| QTL | |||

| ADAMTS20 | 12 | Adamts20 | 15 |

| CASP3 | 4 | Casp3 | 8 |

| CD3E | 11 | Cd3e | 9 |

| CRISP1 | 6 | Crisp1 | 17 |

| CRTAM | 11 | Crtam | 9 |

| HLA Complex | 6 | H2 complex | 17 |

| IL10RA | 11 | Il10ra | 9 |

| IL12RB1 | 19 | IL12rb1 | 8 |

| IL15 | 4 | Il15 | 8 |

| IL2RB | 22 | Il2rb | 15 |

| JAK3 | 19 | Jak3 | 8 |

| LTA | 6 | Lta | 17 |

| LTB | 6 | Ltb | 17 |

| LY6D | 8 | Ly6d | 15 |

| NCAM1 | 11 | Ncam1 | 9 |

| PLEC | 8 | Plec | 15 |

| SOX10 | 22 | Sox10 | 15 |

| THY1 | 11 | Thy1 | 9 |

| TNF | 6 | Tnf | 17 |

| TRHR | 8 | Trhr | 15 |

| TRPS1 | 8 | Trps1 | 15 |

| GWAS and QTL | |||

| HLA-DQA1 | 6 | H2-Aa | 17 |

| HLA-DQA2 | 6 | H2-Aa | 17 |

| HLA-DQB2 | 6 | H2-Ab1 | 17 |

| HLA-DRA | 6 | H2-Ea-ps | 17 |

| Copy number variations | |||

| MCHR2 | 6 | N/A | N/A |

| MCHR2-AS1 | 6 | N/A | N/A |

| Transcriptome expression | |||

| CXCL10 | 4 | Cxcl10 | 5 |

| CXCL11 | 4 | Cxcl11 | 5 |

| CXCL9 | 4 | Cxcl9 | 5 |

| CXCR3 | X | Cxcr3 | X |

| Data based on4,40,42,58,59,62,206,207. | |||

Although most genetic studies in both humans and mice focus on the autoimmune aspects of alopecia areata, the hair loss is largely due to hair shaft fragility and breakage. In the mouse model for alopecia areata, cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 (Crisp1) was identified as a candidate gene within the major alopecia areata locus Alaa1 using a combination of QTL analysis, shotgun proteomics60,61, and in situ hybridization62. Although the autoimmune-based inflammation might dysregulate hair shaft, the lack of development and growth of the hair shaft, lack of CRISP1 in C3H/HeJ mice, the inbred strain most severely affected by spontaneous alopecia areata, suggested that CRISP1 might be an important structural component of mouse hair that predisposes the hair shaft to diseases. Whether this protein plays a role in severity of human disease remains to be determined. Such findings suggest an even more complex genetic involvement, with genetic factors not only involved in disease initiation but also in the pleomorphic clinical presentation.

Pathodynamics of hair loss

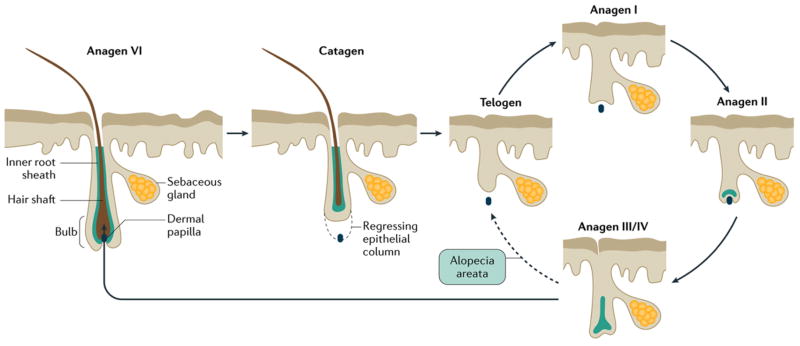

The dynamics of hair growth (FIG. 1) are altered in patients with alopecia areata. An early study63 found that hair loss was preceded by a large increase in the proportion of telogen hairs and an increase in the proportion of abnormal hair shafts, which resulted in increased fragility of the shaft (dystrophic hairs) compared with normal hair from unaffected patients. In normal circumstances, most hairs are in the anagen phase (which is typically divided into six stages: anagen I–VI) and dystrophic hairs are not a feature. In fact, the initial event in alopecia areata seemed to be a rapid progression of hair follicles from the anagen phase to the catagen and telogen phases. Follicles that were less severely affected remained in anagen but produced dystrophic hair shafts that eventually underwent progression to telogen. Biopsies from the margins of expanding lesions of alopecia areata contained large numbers of follicles in catagen or early telogen64. Whether follicles attained telogen via normal catagen transition was not determined. The affected follicles do re-enter the anagen phase. Indeed, one study65 showed that almost 58% of the hair follicles in patchy alopecia areata are in anagen phase.

Figure 1. Hair cycle.

During the anagen phase (the period when a hair follicle is actively growing), which can vary from a few weeks to several years, epithelial cells in the hair bulb undergo vigorous mitotic activity and differentiate as they move distally to form the hair fiber and its surrounding inner root sheath and inner layer of the outer root sheath. Eventually, epithelial cell division ceases, and the follicle enters the catagen phase, in which the proximal end of the hair shaft keratinizes to form a club-shaped structure, which eventually sheds, and the lower part of the follicle involutes by apoptosis. The telogen phase marks the period between follicular regression and the onset of the next anagen phase (solid arrows). The development of the anagen follicle, which closely replicates embryonic development of the hair follicle, is conventionally divided into six stages (I–VI, with anagen VI representing the fully formed anagen follicle)66. In most mammals, hair cycles are coordinated in a wave-like fashion across the skin (moult waves), but in humans, follicles cycle independently of their neighbors. In alopecia areata (dashed arrow), anagen VI follicles are precipitated prematurely into telogen phase. Although they are probably able to re-enter anagen phase, the development of the follicle is halted at the anagen III/IV stage,64,65 when they prematurely return to the telogen phase. Truncated cycles may continue if and until disease activity declines, and follicles are able to progress further into the anagen phase.

Exclamation point hairs (a type of dystrophic hairs) are a key characteristic of AA and are not normally seen in healthy controls64. Although exclamation point hairs might have a well-formed club root identical to that of a normal telogen hair, the root is often narrowed and club hairs fall out more readily than normal. These changes suggested defective anchoring of the hair within the follicle.

Peribulbar inflammation is commonly found around anagen follicles that are adjacent to the focal lesion64. The affected follicles do re-enter anagen. Early lesions showed a reduction in the size of the follicle below the level of the sebaceous gland, with preservation of the section above the sebaceous gland and the gland itself. The smaller anagen follicle is mitotically active, producing a normal inner root sheath. The hair shaft cortex is incompletely keratinized. These changes suggested hair follicle developmental arrest occurs in the anagen IV phase66. Other histopathological studies largely confirmed this study64,65. Indeed, horizontal biopsies from the center of bald patches of patients with alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis found anagen follicles that had failed to develop beyond anagen III/IV phase. The inner root sheath is a conical keratinized structure at this stage, and the hair cortex has just started to differentiate beneath it. Follicles seem to prematurely return to telogen from anagen III/IV and undergo repeated shortened cycles. As alopecia areata activity subsides, the hair follicles progress further into anagen.

Immune response

Target cell

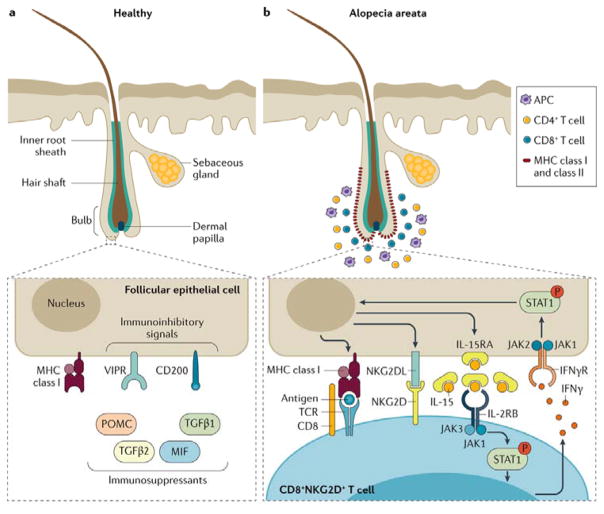

The histopathological feature of alopecia areata is an inflammatory cell infiltrate concentrated in and around the bulbar region of anagen hair follicles (FIG. 2). The hair follicle matrix epithelium that is undergoing early cortical differentiation seems to be the primary target of an immune attack on the hair follicle based on several lines of evidence. First, the matrix cells exhibit vacuolar degeneration (a type of non-lethal cell injury, which is characterized by small, intra-cytoplasmatic vacuoles) in affected anagen follicles67,68, which explains the formation of the exclamation point hair shaft. These degenerative changes lead to a localized region of weakness in the hair shaft, which results in the hair shaft breaking when it emerges from the ostium at the skin surface. Second, the affected hair follicles revert to telogen phase, in which cortical differentiation does not occur. Follicles re-enter the anagen phase normally but do not develop beyond anagen III/IV, the point where cortical differentiation commences. Last, aberrant MHC class I and II expression occurs in the pre-cortical region where the inflammatory cell infiltrates are localized 69.

Figure 2. Breakdown of immune privilege in alopecia areata.

a) Immune privilege of the hair follicle can be achieved through several strategies including: down regulation of MHC class I and β2 microglobulin, which normally stimulate natural killer (NK) cells; local production of immunosuppressants; expression of immunoinhibitory signals (for example, CD200; also known as OX2 membrane glycoprotein); and repression of intrafollicular antigen-presenting cell (APC), perifollicular NK cell and mast cell functions owing to increased levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), released by perifollicular sensory nerve fibers, is also believed to be an immunoinhibitory neuropeptide that might have a role in immune privilege. b) Late anagen hair follicles in patients with alopecia areata have perifollicular infiltrations of APCs, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and abnormal expression of MHC class I and II molecules. CD8+ T cells also infiltrate into the hair follicle root sheaths. Molecules involved in the lymphocyte co-stimulatory cascade are involved in the pathogenesis of alopecia area and provide targets for therapeutic intervention. No inflammatory cells are found in the surrounding of nomal follicles in late anagen phase. INFγ, interferon gamma; IFNγR, interferon gamma receptor; IL2RB, IL2 receptor subunit beta; IL15RA, IL15 receptor subunit alpha; JAK, Janus kinase; NKG2D, NK cell receptor D; NKG2DL, NKG2D ligand; P, phosphorylated; POMC, pro-opiomelanocortin; STAT1, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; TCR, T cell receptor; TGFB, transforming growth factor beta, VIPR, VIP receptor.

Breakdown of immune privilege

The hair follicle is an immune privileged site that prevents autoimmune responses against putative autoantigens expressed in the hair follicle (FIG. 2a)70. Under normal physiological conditions a local immune-inhibitory signaling milieu in and around the hair follicle is generated that suppresses the surface molecules required for presenting autoantigens to NK cells, including CD8+ T lymphocytes. Although the function (or functions) of this hair follicle immune privilege are not proven71–74, it is believed that several autoantigens that are related with pigment production in melanocytes are immunogenic and, under the right circumstances, can result in loss of immune privilege75.

The breakdown of the immune privilege of the hair follicle has been thought to be a major driver of alopecia areata (FIG 2b). Low expression of MHC class I and II molecules and high expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), an NK cell inhibitor, prevent infiltration of a subset of T lymphocytes — CD56+/NKG2D+ NK cells —from the hair follicle of healthy individuals, but prominent aggregations of CD56+/NKG2D+ NK cells are found around hair follicles from patients with alopecia areata. The counts of a subset of CD56+ NK cells expressing NK cell activating receptors (such as, NKG2D and NKG2C) were higher in peripheral blood cells of patients with alopecia areata than in healthy controls, whereas the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors 2D2/2D3 were lower76. GWAS confirmed these observations and linked polymorphisms in the ULBP gene cluster (NKG2D ligands) with susceptibility to alopecia areata4,40, and functional studies showed overexpression of these genes in AA lesional hair follicles of patients with AA. Finally, the expression of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIPR1 and VIPR2), which are located in the hair follicle epithelium, was downregulated in hair bulbs of patients with alopecia areata compared to controls, but VIP ligand expression was normal in nerve fibers which suggests that patients have defects in VIPR-mediated signaling77.

Autoantigen epitopes

The involvement of autoantigen epitopes in the initiation of alopecia areata has been hypothesized. An involvement of melanin, melanin-related proteins and keratinocyte-derived antigens has been suggested based on the observation that white hairs grow back after a period of alopecia and are often spared in further relapses78–82. Administration of synthetic epitopes derived from trichohyalin (structural protein) and tyrosinase-related protein-2 (now known as dopachrome tautomerase, which is involved in pigmentation) induced significantly higher cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in patients alopecia areata than in similarly stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from normal control patients83.

Other Contributing Factors

Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress has a role in alopecia areata and other skin diseases84,85. Significantly higher levels of malondialdehyde (an indicator of lipid peroxidation) and antioxidant activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) were found in blood from patients with alopecia areata than in healthy controls86. In another study, 32% of patients with alopecia areata had antibodies to reactive oxygen species-damaged SOD, whereas no appreciable reaction was found in normal patients84. This suggests that oxidative stress and damage to SOD may play a part in the induction of alopecia areata. A limited genetic study did not find any association between alopecia areata and polymorphisms in SOD2 or GPX1 (encoding for glutathione peroxidase)85.

Vasculature and lymphatic system

In general, inflammation is often associated with increased blood supply to the involved areas, which might include development of new vessels, both blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. Clinical observations revealed that alopecia areata lesions show increased skin temperature, which was interpreted to be the result of increased vascularization87. Other studies have suggested that defective monocytes isolated from patients with long standing alopecia totalis and universalis decreased angiogenic activity relative to normal controls or patients with short term alopecia areata88. Intra-lesional steroid administration, a common treatment for alopecia areata, resolves perivasculitis and is associated with disease resolution89. These observations suggest that vascular changes in lesions play a role in the pathogenesis of this alopecia areata.

Cutaneous lymphatic density in mice declines as they age90. However, in a mouse model of alopecia areata (full thickness skin grafts from C3H/HeJ mice with naturally occurring alopecia areata in younger, healthy C3H/HeJ mice, that is, the skin engraftment model), lymphatic dilation was found 20 weeks after engraftment. Transcriptome analysis of the skin from these mice revealed abnormal transcript levels of genes encoding proteins that acted directly or indirectly on the lymphatic system. Indirect effects included proteins involved in regulating blood pressure or regulations of cellular components of the lymphatic fluid including T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells. Although lymphatic changes alone are a minor part of the pathogenesis of alopecia areata, these changes may collectively contribute to the pathogenesis when considering the ancillary effects beyond the lymphatic system. Identification of these transcripts, many of which do not initially appear to be involved with the autoimmune process, might result in potential new treatment targets91.

Microbiota

The role of the microbiota in the pathogenesis of various diseases is an emerging area of research. The C3H/HeJ mouse strain is not only a model for alopecia areata8 but it was also the first model found to develop a spontaneous form of inflammatory bowel disease92. Inflammatory bowel disease can be a comorbidity of alopecia areata in humans93. The mouse skin graft model for alopecia areata94 showed a variable result when performed at different geographical regions. Although this phenomenon was attributed to high levels of dietary soy bean phytoestrogens in the diet95, the microbiome might also have played a part. Therapeutic manipulation of the microbiome represents an innovative treatment option for many diseases, including alopecia areata, and is a subject for future research.

Environmental triggers

In the majority of cases, no obvious explanation for the onset of an episode of alopecia areata can be found, but a variety of trigger factors have been proposed. The most commonly reported is emotional or physical stress, such as following bereavement or injury17,43. Others include vaccinations, febrile illness, and drugs. A low frequency of alopecia areata was reported to arise shortly after vaccinations against a variety of human pathogens including Japanese encephalitis96, hepatitis B virus97, Clostridium tetani98, herpes zoster virus99, and papillomavirus100. By contrast, one report showed that alopecia areata was triggered or exacerbated by swine flu virus infection101. However, hepatitis B vaccine trials using large numbers of C3H/HeJ spontaneous, adult-onset mouse model of alopecia areata, in which diphtheria and tetanus toxoids were added as controls, suggested that alopecia areata associated with vaccination was in the normal, predicted incidence range102.

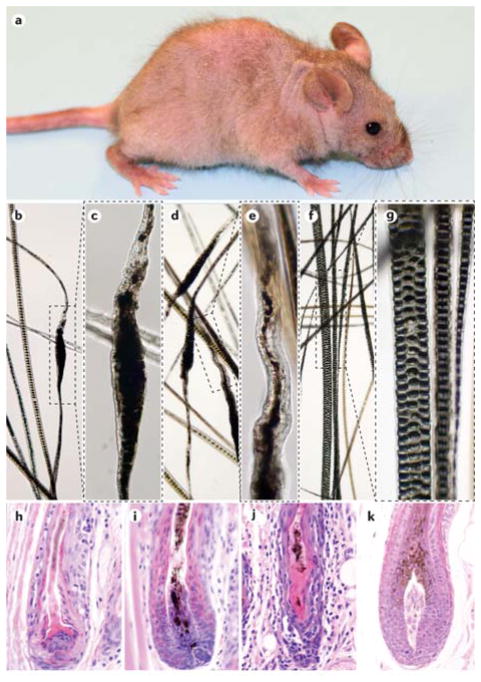

Animal models

Although humans are usually the focus of biomedical research, a wide variety of mammals have been reported to develop alopecia areata. However, of all of these, only the laboratory mouse has held up as a useful species for mechanistic and preclinical studies103,104. Animal models can be used to study disease onset, which is not possible in humans as it is currently not possible to predict who will develop alopecia areata. Although there are biological differences between mouse and human skin (such as wave versus mosaic hair cycle and short versus long anagen stage), phylogenetic conservation is high, including similar diseases, such as alopecia areata105,106. Peribulbar inflammation, a prominent feature of human alopecia areata, is not often found in the mouse owing to the very short anagen stage of the hair cycle in the mouse. In fact, in mice, the inflammation is usually observed above the bulb region but, as in human, is also is associated with MHC class I upregulation107. Both mice and humans with alopecia areata respond to the same types of treatments, both positively and negatively, further validating their usefulness as an animal model (reviewed in REFS108,109).

Several C3H laboratory substrains develop alopecia areata spontaneously. Other inbred strains develop the disorder as well, but the frequency of disease is extremely low110,111. Although C3H/HeJ mice carry a spontaneous mutation in the Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4Lps-d) gene112, the C3H/HeN are wildtype (Tlr4+/+) and otherwise genetically similar; this observation rules out the involvement of Tlr4 in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata as both substrains develop alopecia areata8,110. CBA/CaHN-Btkxid/J mutant mice, a model of human X-linked immunodeficiency, occasionally develop spontaneous alopecia areata110. These mutant mice have a B-lymphocyte-specific defect resulting in their inability to launch an antibody response to thymus-independent type II antigens, which is a natural experiment indicating that alopecia areata is not a humoral autoimmune disease113. Although nail abnormalities are found in a subpopulation of human alopecia areata patients, nail disorders are not found in the inbred strains that develop this disease. However, a single case was reported in a recombinant inbred strain which may prove to be a useful tool to investigate this phenomenon110.

To date, only the C3H substrains have been studied in detail. Spontaneously affected C3H/HeJ mice develop focal alopecia that can wax and wane to become generalized over time (FIG. 3a). The hair loss is associated with structural defects in the hair shafts which lead to breakage compared with normal hair shafts (FIG. 3b–g). A mixture of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in and around hair follicles just above the bulb to the level of the sebaceous gland associated with follicular dystrophy (FIG. 3h–k)114.

Figure 3. C3H/HeJ mouse model of alopecia areata.

a) Alopecia areata in C3H/HeJ mice is shown (part a). Spontaneous alopecia development in C3H/HeJ mice starts with patchy alopecia areata in the axillary and inguinal regions, which spreads across the ventral skin to the dorsal skin and eventually results in diffuse alopecia. Note that the fine hair of the tail and ears are not involved. Analysis of the hair of C3H/HeJ mice with alopecia areata (parts b–e). The regular sepate or seputulate (ladder-like) pattern of the normal hair medulla (part f and part g) is lost and the hair shaft becomes thin and serpentine (parts b–e). These deformities weaken the hair and result in shaft breakage (parts b–e). Normal hair shafts from an unaffected C3H/HeJ mouse reveal the regular septulate (3 rows) and septate (1 row) cellular pattern within the hair shafts (part f and part g). Parts c, e and g are enlargements of the boxes in parts b, d and f, respectively. Histopathological analysis of skin is shown (parts h–k). Mice with alopecia areata have various degrees of inflammation and follicular dystrophy in and around the anagen hair shafts (parts h–j). A healthy, late anagen stage hair follicle is shown in part k.

Mouse models were used to identify a variety of epitopes that appear to be specific for alopecia areata. Class I MHC-restricted 1MOG244.1 CD8+ T cells in a normally resistant C57BL/6J mouse model are capable of independently producing effector responses necessary for alopecia areata development and full progression. The 1MOG244.1 T cell clone in this mouse model independently mediates AA and was proposed as a potential tool to use for antigen screening115. This was the first indication that a specific epitope might cause alopecia areata.

The relatively low frequency (20–25% penetrance), late disease onset, and waxing and waning course of spontaneous alopecia areata in C3H/HeJ mice8 reduced the value of this mouse as a research or preclinical tool. However, full thickness skin grafts from affected, older C3H/HeJ to young, clinically normal C3H/HeJ females resulted in a highly reproducible model in which the mice had diffuse alopecia areata by 10 weeks after engraftment and generalized baldness 20 weeks after engraftment94,116,117. Cells obtained from lymph nodes draining affected areas of skin, and even long-term cultures of these cells, can also be used to induce alopecia areata in young, histocompatible mice of the same strain118. This strategy has the advantage of circumventing skin graft surgery and to study the pathophysiology of alopecia areata at an early stage, before hair loss. Humanized mice with various mutations causing immunodeficiency that are implanted with human skin grafts with or without alopecia areata and given various types of human T cells are another model. Although it has been used successfully, this approach has very limited use to date due to difficulty of most groups getting access to human skin biopsies and/or peripheral blood leukocytes119. Finally, a rat model (that is, the Dundee experimental bald rat) was identified and studied in detail7 but, this model is no longer used due to its large size, expense of maintaining colonies relative to mice, and limited reagents for working with rat samples103.

Diagnosis, screening, and prevention

Clinical features

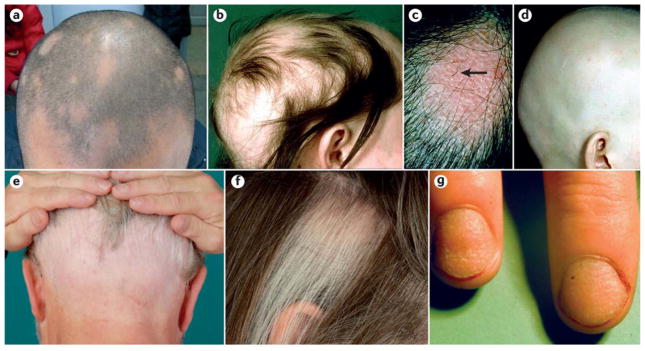

Initially, alopecia areata is diagnosed by identification of waxing and waning focal alopecia anywhere on the body but most often on the scalp (FIG. 4a–b). Although the scalp is often the first affected site, any and all hair-bearing skin can be affected. Patches of hair loss within the beard can be conspicuous in dark haired men. Likewise, eyebrows and eyelashes may be the only sites affected. The skin in the affected areas appears normal or slightly reddened (FIG. 4c). Exclamation point hairs are often seen at the margins of these lesions during active phases of the disease. Subsequent progress is unpredictable; the initial patch can expand or regrow hair within a few months, or further patches may appear after various time intervals. A succession of discrete patches may coalesce to give large areas of hair loss. In some cases, this progresses to alopecia totalis (FIG. 4d) or alopecia universalis; sometimes, specific areas are affected such as in ophiasis (FIG. 4e). In a minority of patients hair loss is initially diffuse without the development of discrete bald patches. Regrowth may initially present as fine and non-pigmented hair, but usually the hairs gradually regain their normal thickness and color. Regrowth in one region of the scalp may be associated with expanding areas of alopecia elsewhere120,121.

Figure 4. Clinical manifestations of alopecia areata.

a) Limited patchy alopecia areata (<50% scalp involvement). b) Extensive patchy alopecia areata (>50% scalp involvement). c) Active patch of alopecia areata showing exclamation point hairs (arrow) and slight skin erythema. d) Alopecia universalis. e) Ophiasis pattern of alopecia areata. f) Sparing of white hairs in alopecia areata. g) Nail pitting and longitudinal striations (trachyonychia) associated with alopecia areata. Part c and part f are reproduced with permission from REF 208, Wiley. Part e is reproduced with permission from REF 209, Springer.

Part c and part f are reproduced with permission from Messenger, A. G., Sinclair, R. D., Farrant, P. & de Berker, D. A. R. in Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology 9th edn (eds Griffiths, C., Barker, J., Bleiker, T., Chalmers, R. & Creamer, D.) 89 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), Wiley. Part e is reproduced with permission from Bohm, M. in European Handbook of Dermatological Treatments (eds Katsambas, A. D., Lotti, T. M., Dessinioti, C, & D’Erme, A. M.) 45-53 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2015), Springer

White (uncolored) hairs are often spared in alopecia areata (FIG. 4f). In those with a mixture of pigmented and non-pigmented hair, alopecia areata preferentially affects pigmented hair resulting in sparing of the white hair resulting in a dramatic change in hair color if the alopecia progresses rapidly. Sparing of white hair is a relative phenomenon; white hairs, although less susceptible to the disease, are not immune to it. In a mouse model where pigment loss was created in a focal manner using freeze branding, white hairs were not preferentially spared122. However, in humans, white hair sparing might reflect effects of the autoimmune attack on the bulb region during the period when pigment is produced68.

Alopecia areata can involve the nails, abnormalities of which are observed in about 10–15% of cases referred to a dermatologist and up to 44% in some populations123–125. Patients with nail problems usually exhibit the more severe forms of hair loss (50.5% of patients with severe alopecia have nail abnormalities versus 13% of patients with patchy alopecia, P<0.01)125. Alopecia areata is usually associated with fine stippled pitting of the nails; some cases have less well-defined roughening of the nail plate with longitudinal striations (trachyonychia) (FIG. 4g). The nail dystrophy can be the most troublesome aspect of the disease. In a large study of 1,000 patients with alopecia areata with nail lesions, only pitting was significantly more often found than other nail defects in children than adults125.

Disease course and prognosis

The potential for regrowth of hair in patients with alopecia areata is retained for many years and is possibly life-long, as the disease process does not destroy hair follicles. This is an important difference between alopecia areata and the scarring forms of alopecia, which destroy the hair follicle and result in irreversible hair loss (BOX 1). The long-standing notion that patients with chronic alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis lose the ability to regrow hair probably stems from an historical difficulty in treatments by previously available topic and oral medications. Patches of hair loss may occur at infrequent intervals interspersed with long periods of complete remission. In other patients, alopecia areata is more persistent such that new areas of alopecia continue to develop as other areas resolve. Referral centers indicate that 34–50% of patients will recover spontaneously within 1 year, although most will experience multiple episodes of the alopecia, and 14–25% of patients will progress to alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis, from which full recovery is unusual (<10% of patients)10,11,126. One Japanese study reported spontaneous remission in 80% of patients within 1 year for those with a small number of circumscribed patches of hair loss12. The best indication for a prognosis is the extent of hair loss when first diagnosed126. A less favorable prognosis is observed with childhood onset alopecia areata and ophiasis126,127. A later age of onset correlates with less extensive alopecia27,128,129. Severe alopecia areata (alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis) usually occurs before 30 years of age129 and is often associated with nail dystrophy (trachyonychia) 128–130.

Classification of severity

Alopecia areata is conventionally classified as patchy, alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis (BOX 2). A more detailed classification should include the disease duration and, with regard to patchy alopecia areata, the extent of the hair loss. Description of the pattern should include the presence of ophiasis, the involvement of sites on the trunk and limbs as well as the beard and eye lashes, and the presence of nail disease. A scoring system based on these features, the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, has been devised131. An alopecia areata progression index was also developed in which the scalp surface was divided into 4 quadrants. Hair loss in each quadrant was scored based on percentage of hair lost and clinical findings132.

Investigations

The diagnosis of alopecia areata is usually made on clinical grounds and, in most cases, further tests are not needed. However, a number of tools, such as dermoscopy or histopathology, can further validate the diagnosis (FIG. 5).

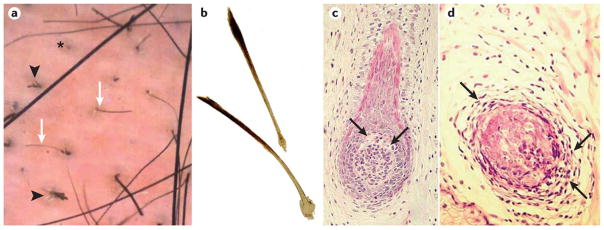

Figure 5. Diagnostic tools to validate and differentiate alopecia areata.

a) Dermoscopy of the skin of patient with alopecia areata. Black arrowheads point to dystrophic, cadaverized and twisted hairs. The asterisk denotes a yellow dot with follicular plugging by keratinaceous debris. White arrows point to short, regrowing miniaturized hairs. b) Plucked exclamation point hairs are characterized by proximal hair shaft narrowing and are always broken; they might show reduced pigmentation. c) Histopathology of a vertical section of a skin biopsy from patch of alopecia areata with very early regrowth of hypopigmented hair. An early anagen hair bulb with vacuolar degeneration (arrows) of epithelial cells around the upper pole of the dermal papilla. d) A horizontal section from a similar area showing lymphocytic infiltrate (arrows) surrounding and infiltrating an anagen hair bulb. Part b is reproduced with permission from REF 208, Wiley. Part c is adopted with permission from REF64, Wiley.

Part b is reproduced with permission from Messenger, A. G., Sinclair, R. D., Farrant, P. & de Berker, D. A. R. in Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology 9th edn (eds Griffiths, C., Barker, J., Bleiker, T., Chalmers, R. & Creamer, D.) 89 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), Wiley. Part c is adapted with permission from Messenger, A. G., Slater, D. N. & Bleehen, S. S. Alopecia areata: alterations in the hair growth cycle and correlation with the follicular pathology. Br. J. Dermatol. 114, 337-347 (1986), Wiley

Dermoscopy

The advent of dermoscopy (that is, examination of the skin using a skin surface microscope) provided an additional tool for diagnosis of alopecia areata and differentiation from other hair loss disorders that may present in a similar fashion133. The key dermoscopic features of alopecia areata are yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, exclamation point hairs and short vellus hairs, which are a sign of early regrowth (FIG. 5A).

Histopathology

If there is diagnostic uncertainty, a skin biopsy might be necessary although the histological features can be subtle; evaluation by an experienced pathologist is needed to confirm the diagnosis. A skin biopsy can be helpful to diagnose diffuse alopecia areata and to differentiate early scarring alopecia. Alopecia areata is a dynamic disease that is reflected in its histopathologic features (FIG. 5c–d)64. Both transverse and horizontal sections are important to review to obtain an accurate histopathological diagnosis of alopecia areata.

In biopsies taken from the margin of an expanding bald patch, newly affected anagen follicles typically show a lymphocytic infiltrate around and within the hair bulb. Eosinophils and CD1+ and CD8+ cells can also be found within the infiltrate. A large increase in follicles in catagen and telogen phase is seen in the early stages of the disease. The catagen stage may be disorganized with follicles containing remnants of disrupted hair fibers. Biopsies from established bald patches show a normal number of hair follicles devoid of terminal hair fibers. Follicles below the level of the sebaceous gland are miniaturized and have telogen or anagen morphology. However, the miniaturized follicles are limited to early stages of anagen development. A peribulbar and intrabulbar inflammatory infiltrate is associated with anagen but not telogen follicles and tends to be less pronounced than in the initial stages of the disease. Other features include pigmentary incontinence (melanin granules within dermal macrophages or free in the dermis secondary to epithelial cell injury) concentrated in follicular dermal papillae and degeneration of hair bulb epithelium around the upper pole of the dermal papilla in anagen follicles120.

Differential diagnosis

Alopecia areata needs to be differentiated from other types of non-cicatricial alopecia, cicatricial alopecia, and genetic conditions associated with hair loss (Box 1). In children, tinea capitis and trichotillomania are the most common diseases mistaken for alopecia areata. In addition, the early stages of scarring alopecia might be difficult to differentiate. The diffuse form of alopecia areata is perhaps the most difficult to identify and may require a detailed history to uncover previous episodes of hair loss, nail dystrophy and the usually rapid progression of the hair loss. The development of alopecia universalis in infancy should alert the clinician to the possibility of atrichia with papular lesions (also called papular atrichia), which is due to rare, autosomal recessive mutations in the hairless (HR)134 or the vitamin D receptor (VDR) genes135. Hair loss in patients with VDR mutations may also be partial. Besides specific differences in clinical presentation, additional investigations such as dermoscopy and histopathology are helpful to differentiate these conditions from alopecia areata. On the basis of clinical suspicion, other diagnostic tests can include fungal culture, serology for lupus erythematosus erythematosus or syphilis serology.

Management

General principles

Several treatments can induce hair growth in alopecia areata but few have been tested in randomized controlled trials and there are few published data on long-term outcomes; none have been approved by the US FDA, although there guidelines and treatment options available in other countries136,137. Some patients do respond well to currently available treatments, but the response rate in those with severe alopecia areata types (alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis or a combination) remains low. A high level of immune reactivity is present in patients with alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis than in normal controls9.

Not all patients need or wish for active treatment. Remission might occur spontaneously in patients with limited patchy hair loss of short duration (< 1 year)12,126. Although reassurance alone might be adequate in this patient group, advice should make clear that regrowth will take >3 months of the development of any individual patch. Long-standing extensive alopecia areata has a less favorable prognosis and currently, all treatments have a high failure rate. These patients might prefer not to be treated or opt for cosmetic options. For many patients the overriding issue is how to cope with ongoing or recurrent hair loss, and the clinician has an important role in helping patients deal with this. Counseling should include an explanation of the nature of the disease and the disease course, the treatments available and their chances of success. Some patients might require psychological support.

Medical management

Local corticosteroids

A potent topical steroid (for example, clobetasol) delivered in a lotion, foam, or shampoo formulation can be used for limited patchy alopecia areata and may speed recovery of hair growth in mild degrees of alopecia areata138–140. Treatment should be continued for at least three months but should be stopped after 6 months if there is no response. Folliculitis (inflammation of the hair follicles) is an occasional complication. Topical steroids are ineffective to treat alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis.

Intralesional steroid application is probably the most effective treatment in patchy alopecia areata. A slow release steroid (such as hydrocortisone acetate or triamcinolone acetonide) administered by fine needle injection or by a needleless device into the upper subcutaneous tissue can stimulate hair growth at the site of injection in some patients141,142, but multiple injections are usually needed. Local cutaneous atrophy is a common adverse effect but recovers within a few months. Intralesional steroid administration will not prevent the development of alopecia areata at other sites and is not suitable for patients with rapidly progressive patchy alopecia areata, alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis. Mechanistic studies revealed that the increased abundance of CD3+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD11c+ dendritic cells and CD1a+ Langerhans cells in and around hair follicles in alopecia areata decreased following intralesional corticosteroid treatment. In addition, downregulation of genes encoding several interleukins and chemokines (such as IL12B, CC-chemokine ligand 18 (CCL18), and IL32) and upregulation of genes encoding several keratins (KRT35, KRT75, and KRT86) were observed following intralesional steroid administration compared with levels before injection. These results suggest that these genes may be useful biomarkers for monitoring steroid treatment in patients with alopecia areata143. Various other treatments, such as topical minoxidil (a vasodilator) and anthralin (also known as dithranol; which has antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory effects), have been advocated in patients with limited patchy alopecia areata but their benefits are uncertain137.

Systemic corticosteroids

Long-term daily treatment with oral corticosteroids might result in regrowth of hair, and this strategy has successfully been used for extensive and rapidly progressive alopecia areata. A small, partially controlled study showed that 30–47% of patients with mild to extensive alopecia areata who were treated with a 6-week tapering course of oral prednisolone showed >25% hair regrowth144. However, in most patients, continued treatment is needed to maintain hair growth and the response is usually insufficient to justify the adverse effects. Several case series have reported favorable responses to high-dose pulsed corticosteroid treatment using different oral and intravenous regimens145–147. However, the only controlled trial showed that patients receiving prednisolone once weekly for three months showed better hair regrowth at six months than those taking a placebo, but this was not statistically significant148.

Contact immunotherapy

Contact immunotherapy is an effective treatment for some patients with patchy alopecia areata. The application of a potent allergen to a small area on the scalp sensitizes the patient. The same allergen, in a concentration sufficient to induce a mild contact dermatitis, is then applied weekly. Contact allergens used in this treatment include dinitrochlorobenzene, squaric acid dibutylester and diphenylcyclopropenone, with diphenylcyclopropenone being most commonly used. Although the mode of action of contact immunotherapy is unknown, antigens might induce ‘antigenic competition’ and attract CD4+ T away from the perifollicular region149. Other proposed mechanisms include the non-specific stimulation of T suppressor cell in the skin150, increased local expression of TGFB151, and activation of myeloid suppressor cells that, via ζ-chain down-regulation, contribute to auto-reactive T cell silencing152.

Although the published response rates vary widely (9–87%), in general, 20–30% patients achieve a response considered to be worthwhile, such as sufficient regrowth to enable patient to manage without a wig153. Less favorable responses were reported in patients with extensive hair loss154,155. Adverse prognostic features include the presence of nail abnormalities, an early onset of alopecia, a positive family history and failure to sensitize (which does occur but is rare in our experience)153. Treatment is usually discontinued after 6 months if no response is obtained. One study showed clinically significant regrowth in approximately 30% and 78% of patients after 6 months and 32 months of treatment, respectively, suggesting that more prolonged treatment is required to achieve a favorable outcome156. The response in patients with alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis was only 17%, which did not improve upon prolonged treatment beyond 9 months. Unfortunately, 62% of successfully treated patients showed relapse. In children, response rates of 33%157 and 32%158 have been reported. Another study found a similar short-term response in children with severe types of alopecia areata, but <10% experienced sustained benefit159.

No long-term side effects have been reported associated with contact immunotherapy in >30 years use. Severe dermatitis is the most common adverse event, but careful titration of the drug concentration can reduce the risk. Transient occipital and/or cervical lymphadenopathy are also frequent, and can persist throughout the treatment period. Uncommon adverse effects include urticaria160 and vitiligo161. In patients with racially pigmented skin, hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation (including vitiligo) can occur. Health professional sensitization (doctors, nurses and pharmacy technicians involved in delivering contact immunotherapy) is a considerable problem, and care should be taken to avoid skin contact with the allergen by those administering the drugs.

Other treatments

A response to methotrexate (an immune suppressant) has been reported in several case series162–164. However, many patients also received systemic corticosteroids, and owing to the lack of controls, this makes it difficult to assess the magnitude of any benefit. Although a small case series suggests a response to cyclosporin (a calcineurin inhibitor), the benefits are probably too small and inconsistent to justify its use in view of the possible adverse effects165. Topical tacrolimus (an immune suppressant) is ineffective166. With the exception of isolated case reports, anti-TNF biologic agents have not been shown to be effective for alopecia areata. An open-label study with etanercept revealed no efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe alopecia areata167. In addition, patients who have been treated with adalimumab, infliximab or etanercept for other autoimmune disorders have developed alopecia areata during the course of treatment168,169. Finally, small randomized trials of efalizumab (anti-CD11A)170 and alefacept (anti-CD2)171 showed no benefit in alopecia areata.

Non-medical treatments

Laser treatment

Laser therapy may have a positive effect on patients with alopecia areata. The Excimer laser (ultraviolet laser) is currently commonly used and may offer a safe and effective alternative to medical treatments. However, recent reviews and reports indicate that randomized controlled clinical trials are needed to confirm this is a better approach than medical treatment, as the only result might be an increase in hair shaft diameter172,173. Preclinical trials with the mouse model for alopecia areata did not show efficacy using a laser comb174.

Photochemotherapy with all types of PUVA (oral or topical psoralen, local or whole body UVA irradiation) claim success rates of up to 60–65% for alopecia areata in uncontrolled studies175–177, but results are inconsistent. Retrospective reviews reported low response rates178 or response similar to natural course of the disease179. Relapse rates are high and continued treatment is usually needed to maintain hair growth, which may lead to an unacceptably high cumulative UVA dose.

Cosmetic strategies

Women with extensive alopecia might decide to wear a wig, hairpiece or bandana. Men tend to shave their heads, although some opt for a wig. The use of semi-permanent tattooing can be helpful to disguise loss of eyebrows.

Psychological support

For many patients with extensive patchy alopecia areata, alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis, current medical treatments fail. The individual coping response to alopecia varies from the alopecia being an inconvenience that has little or no impact on leading a normal life through to a life-changing experience that can have a devastating impact on psychological well-being with consequences that include clinically significant depression, loss of employment and social isolation180. The clinician has an important role in recognizing the psychological impact of alopecia and in helping the patient to overcome and adapt to this issue. Some patients will need professional support from a clinical psychologist or other practitioner skilled in managing disfigurement. Many benefit from contact with patient support organizations, for example the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (https://www.naaf.org/) and Alopecia UK (http://www.alopeciaonline.org.uk/). In children, alopecia areata can be particularly difficult to deal with. If a parent feels there is a considerable change in the needs of their child (withdrawn, low self-esteem, failing to achieve at school and/or change in behavior) the child may need to be referred to a pediatric clinical psychologist, educational psychologist, or social worker (https://www.naaf.org/alopecia-areata/living-with-alopecia-areata/alopecia-areata-in-children)137.

Quality of life

Psychological stress levels, frequency of psychiatric disease and levels of psychiatric symptoms are usually reported to be higher in adult patients with alopecia areata than controls, but contradictory reports exist. In one study, 8.8% of patients with alopecia areata experience major depression throughout their lifetime, 18.2% experience generalized anxiety disorder, 3.5% social phobia and 4.4% paranoid disorder17. Another study reported that alopecia areata is associated with poor psychiatric status and QOL, especially in childhood181. This study indicated that children with alopecia areata were more likely to have a depressive mood than adolescents with alopecia areata. The explanation for this difference is not clear as the impact on QOL of children and adolescents occurs through both clinical and psychiatric parameters which are very complicated181. More in-depth and accurate studies to identify which factors impact QOL of patients with alopecia areata are needed.

The effects of alopecia, including alopecia areata, on physical health status is measured by morbidity and mortality data commonly used to evaluate health conditions, but the QOL of alopecia patients may significantly differ (Box 4)182,183. The physical, mental and social aspects of a healthy person with alopecia is very different from those individuals with chronic medical or physical disability. Female pattern hair loss and alopecia areata do not cause physical disability but have mental and social effects affecting QOL184.

Box 4. Reduced QOL in severe alopecia areata.

Sustainable cosmetic hair growth uncertain

Hair pattern regrowth variable and unpredictable

Multiple environmental and genetic triggers

May be more severe than the mental or physical effects

QOL, quality of life.

To address the need to better define factors affecting QOL of patients with alopecia areata, self-assessment health instruments, such as Dermatology Life Quality Index and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), are used5,183. Alopecia areata-specific instruments have also been developed, including the Alopecia Areata Quality of Life Index, Alopecia Areata Quality of Life and Alopecia Areata Symptom Impact Scale.183 Health-related QOL assessments using Skindex-16 (a brief version of Feel of Negative Evaluation Scale and Dermatology Life Quality Index) of 532 patients enrolled in the US National Alopecia Areata Registry were compared to previously reported health-related QOL levels from healthy controls and patients with other skin diseases5. Risk factors for poor health-related QOL were age 20–50 years of age, female sex, light skin color, hair loss of 25–99% on the scalp surface, family stress and change in employment. Another study searched six electronic databases of 479 studies on effects of alopecia areata on health-related QOL; 21 studies with 2,530 patients met inclusion criteria.183 The meta-analysis of SF-36 studies detected a significantly reduced health-related QOL across the role-emotional, mental health and vitality domains (P<0.001). Scalp involvement, anxiety and depression had a negative effect on health-related QOL with conflicting results for age, gender, marital status and disease duration, but wearing a wig had a positive impact183. Alopecia areata has a profound effect on self-awareness owing to the psychological impact of negative beliefs and emotions185. More attention should be given to the effect of alopecia areata on QOL.

Outlook

Patient stratification

Textbooks list numbers of patients tested in various studies, outcomes and effectiveness ratings for the classic types of alopecia areata (Box 2), and these patient categories still form the basis for treatment decisions to date186. Indeed, these broad subtypes have been used to stratify patient for treatment and clinical trials when little was known about the underlying pathophysiology of alopecia areata and when no biomarkers were available.

Future treatment strategies

There currently are no US FDA-approved treatments for alopecia areata, although some European guidelines discuss treatment options137. No treatment approaches have been consistently effective in large numbers of patients. As the molecular mechanisms of alopecia areata are further defined and rationally designed trials are initiated, clinicians can consider using targeted therapies. Adverse effects of many of these treatments are important considerations, but as more drugs are identified, it is possible that combinations at lower dosages and/or topical applications will achieve results with acceptable safety profiles. For a disease that has been largely untreatable, the exponential rate of progression in technological developments in the last 25 years indicates that efficacious therapies are possible in the foreseeable future.

Antibodies and biologics

The similarity of the molecular and clinical aspects of alopecia areata between humans and mice has integrated investigations between the species and has both revealed and validated potential targets. For example, the first transcriptome study of humans and mice identified a dysregulated transcript, CTLA4 in humans and Clta4 in mice, which encodes cytotoxic T lymphocyte protein 4, a co-stimulatory T-cell ligand that binds CD80 (formerly B7.1) and CD86 (formerly B7.2) on antigen presenting cells. As in other autoimmune diseases, this pathway can be targeted with recombinant CTLA4-immunoglobulin to treat alopecia areata4,57,187,188. Increased expression of IFN-response genes (including CXCL9 (which encodes CXC-chemokine ligand 9), CXCL10, and CXCL11) was found in several human and mouse transcriptome studies2,58,189,190. Monoclonal antibodies against these cytokines seem to be effective in mouse models, paving the way for additional clinical approaches to treating patients191. Patients with alopecia areata had significant increase in IL12 and IL23 in their skin compared with normal patients who were treated with ustekinumab, a human monoclonal antibody which is targeted to these cytokines. This small series of patients had a gradual improvement at 20 and 28 weeks of treatment and full hair regrowth by week 49192. Secukinumab is a human IL17A antagonist that is currently indicated for the treatment of adult patients with plaque psoriasis, active psoriatic arthritis and active ankylosing spondylitis. Clinical trials are in progress for using this to treat alopecia areata 193

JAK inhibitors

The human genetic studies and gene expression analyses have revealed that molecular pathways upstream of the JAKs were often disrupted in alopecia areata (FIG. 2)4,40. Several JAK inhibitors are approved by the US FDA for clinical use for treating other diseases, such as myelofibrosis (ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor) and rheumatoid arthritis (tofacitinib, a pan-JAK inhibitor). These drugs have been shown to be effective in both preventing and reversing AA in preclinical trials using the C3H/HeJ mouse model, when given topically as well as orally2. Several case series and individual reports have documented regrowth of hair in patients with different forms of alopecia areata, including alopecia universalis, following treatment with oral JAK inhibitor drugs. Three JAK inhibitors have been used: tofacitinib194–198, ruxolitinib2,199,200, and baricitinib (JAK 1/2 inhibitor)201. Hair regrowth has also been observed when treating human patients with JAK inhibitors for other diseases who have concurrent alopecia areata. Although the number of reports is small, and no randomized, placebo-controlled studies have yet been performed, the response in patients with severe alopecia (in which spontaneous remission is rare) strongly suggests a therapeutic effect. Not surprisingly, there have been several reports of relapse following initial improvement in patients treated with ruxolitinib and tofacitinib196,197,200,202, suggesting that an eventual therapeutic regimen may need to include long-term maintenance therapy. The overall positive results in these early clinical studies are supported by the results of JAK inhibition in a mouse model of alopecia areata and by an improved understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease. Several clinical trials are now underway to rigorously test the efficacy of oral and topical JAK inhibitors using larger and placebo-controlled studies.

Stem cell approaches

Stem cell educator therapy has shown some initial success203. This approach uses a closed-loop system to isolate mononuclear cells derived from patients with alopecia areata, allows them to interact with human cord blood-derived multipotent stem cells, and then returns the “educated” cells into the patient’s circulation. Using this treatment, patients with severe alopecia areata had improvement in both hair regrowth and QOL. The underlying mechanism appeared to be upregulation of T helper (TH2) cytokines and the restoration of balancing TH1, TH2 and TH3 cytokine production.

Taken together, basic science approaches have identified a series of molecular targets, many of which already have approval in some countries. Combinations of these drugs may become commonly used to treat AA patients in the not too distant future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (R01AR056635 to J.P.S.; and P50AR070588, R01AR065963, R01AR056016, U01AR067173 and R21AR061881 to A.M.C.) and the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (J.P.S., L.E.K., and A.M.C.). Core facilities at The Jackson Laboratory were supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA034196).

Footnotes

Author contributions

Introduction (C.H.P., L.E.K., A.G.M., A.M.C., J.P.S.), Epidemiology (C.H.P., L.E.K., J.P.S.), Mechanisms/pathophysiology (C.H.P., L.E.K., A.M.C. J.P.S.), Diagnosis, screening and prevention (A.G.M., A.M.C., L.E.K., J.P.S.), Management and therapeutic approaches (L.E.K., A.G.M., A.M.C.), Quality of life (A.G.M., L.E.K., J.P.S.), Outlook (L.E.K., A.G.M., J.P.S.), Overview of the Primer (J.P.S).

Competing interests

L.E.K. is on the scientific advisory committee for the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF) and Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation (CARF). A.M.C. is on the scientific advisory committee for NAAF and is a consultant for Aclaris Therapeutics, Inc. J.P.S. has or has had sponsored research contract with Biocon LLC and the NAAF for preclinical trials using mouse models for alopecia areata, and is on the scientific advisory committee for NAAF and Chairman for CARF. C.H.P. and A.G.M. have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.McElwee KJ, et al. Comparison of alopecia areata in human and nonhuman mammalian species. Pathobiology : journal of immunopathology, molecular and cellular biology. 1998;66:90–107. doi: 10.1159/000028002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xing L, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043–1049. doi: 10.1038/nm.3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duvic M, et al. The national alopecia areata registry-update. J Invest Dermat Symp Proc. 2013;16:S53. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petukhova L, et al. Genome-wide association study in alopecia areata implicates both innate and adaptive immunity. Nature. 2010;466:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature09114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi Q, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in alopecia areata patients-a secondary analysis of the National Alopecia Areata Registry Data. J Invest Dermat Symp Proc. 2013;16:S49–50. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michie HJ, Jahoda CAB, Oliver RF, Johnson BE. The DEBR rat: an animal model of human alopecia areata. Brit J Dermatol. 1991;125:94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb06054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliver R, et al. The DEBR rat model for alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:97S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12472251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundberg JP, Cordy WR, King LE. Alopecia areata in aging C3H/HeJ mice. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:847–856. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12382416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabbari A, et al. Molecular signatures define alopecia areata subtypes and transcriptional biomarkers. EBioMedicine. 2016;7:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gip L, Lodin A, Molin L. Alopecia areata. A follow-up investigation of outpatient material. Acta Derm Venereol. 1969;49:180–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker SA, Rothman S. A statistical study and consideration of endocrine influences. J Invest Dermatol. 1950;14:403–413. doi: 10.1038/jid.1950.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeda T. A new classification of alopecia areata. Dermatologica. 1965;131:421–445. doi: 10.1159/000254503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ro BI. Alopecia areata in Korea (1982–1994) J Dermatol. 1995;22:858–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1995.tb03936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safavi K. Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:702. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1992.01680150136027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, Moshell AN, Melton LJ. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmstead County, Minnesota 1975–1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628–633. doi: 10.4065/70.7.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]