Abstract

The formation of amyloid fibrils has been associated with many neurodegenerative disorders, yet the mechanism of aggregation remains elusive, partly because aggregation timescales are too long to probe with atomistic simulations. A microscopic theory of fibril elongation was recently developed that could recapitulate experimental results with respect to the effects of temperature, denaturants, and protein concentration on fibril growth kinetics (Schmit, J. Chem. Phys. 2013). The theory identifies the conformational search over H-bonding states as the slowest step in the aggregation process and suggests that this search can be efficiently modeled as a random walk on a rugged one-dimensional energy landscape. This insight motivated the multi-scale computational algorithm for simulating fibril growth presented in this paper. Briefly, a large number of short atomistic simulations are performed to compute the system diffusion tensor in the reaction coordinate space predicted by the analytic theory. Ensemble aggregation pathways and growth kinetics are then computed from Markov State Model (MSM) trajectories. The algorithm is deployed here to understand the fibril growth mechanism and kinetics of Aβ16-22 and three of its mutants. The order of growth rates of the wild-type and two single mutation peptides (CHA19 and CHA20) predicted by the MSM trajectories is consistent with experimental results. The simulation also correctly predicts that the double mutation (CHA19/CHA20) would reduce the fibril growth rate, even though the degree of rate reduction with respect to either single mutation is over estimated. This artifact may be attributed to the simplistic implicit solvent model. These trends in the growth rate are not apparent from inspection of the rate constants of individual bonds or the lifetimes of the mis-registered states that are the primary kinetic traps, but only emerge in the ensemble of trajectories generated by the MSM.

Introduction

Protein aggregation has been implicated in a large number of conditions like Alzheimer’s and prion diseases.1–2 Interestingly, evidence suggests that the pathogenic species are metastable oligomers rather than the fibril states that represent the thermodynamic ground state. 3–6 This observation implies that the mechanism of disease progression hinges on the rates of processes that determine the flux of protein into and out of pathogenic states. These processes include protein synthesis, oligomer formation, oligomer dissolution, fibril nucleation, fibril elongation, and protein degradation. While there is ample evidence that the cross-beta core structure of amyloid aggregates is an intrinsic property of the peptide backbone7–14, aggregation rates are known to be highly dependent on mutations and length variants15. Therefore, the microscopic details encoded in the amino acid side chains play a key role in disease progression.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are uniquely suited to investigate the fine details of molecular processes involved in aggregation, because they permit inspection at spatial and temporal resolutions that are not accessible by experiments or other theoretical approaches 16–18. However, such approaches are constrained by computational cost which limits the timescales accessible to detailed simulations. Experiments have shown that the elongation of established fibrils in the reaction-limited regime (i.e. high concentration) requires roughly a second per molecule added.19–20 These timescales are currently accessible only with coarse-grained models, 18, 21. For example, the aggregation process has been studied using various 3- and 4-bead CG models21–25. However, these CG models are usually inadequate to distinguish various sidechains with subtle differences and are not generally suitable to understand specific sequence effects on fiber formation. These effects will require multi-scale algorithms capable of resolving both fine spatial details and long timescales.

The long timescales characterizing aggregation are somewhat puzzling because fibrils are essentially very long beta sheets and secondary structures typically form in sub-microsecond timescales during protein folding1, 17. The difference is that native proteins are under a pressure to evolve folding pathways that provide a bias toward the folded state, often described in terms of funnel shaped free energy landscape.26–27 Pathogenic aggregates are not subjected to this evolutionary pressure and, therefore, are more prone to becoming trapped in unproductive pathways. In a recent paper we introduced a simple theory showing that the exploration of parallel productive and unproductive pathways appears adequate to recapitulate the effects of protein concentration, denaturants, and temperature on fibril elongation.28 This theory describes the aggregation process in terms of two reaction coordinates; the number of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) formed between the fibril and incoming molecule and the alignment between them (henceforth referred to as the ‘registry’). These coordinates are characterized by very different timescales. H-bonds formation and breakage occurs in nanoseconds, yet the time it takes to explore different registries depends exponentially on the peptide length and can be many orders of magnitude longer. This is because a registry shift requires a high-energy fluctuation in which all of the H-bonds are broken. Thus, aggregation is a slow process because the molecules must explore many different registries. This random search over binding states is similar to the combinatorial problem observed by Levinthal in the protein folding problem29. When proteins fold to a functional native state the problem is solved by a biased energy landscape that limits the conformational space. In amyloid aggregation the combinatorics are constrained by the number of registries accessible to the β-sheets.

In this paper we use our theory as guidance in constructing a multi-scale computational algorithm that can resolve fine spatial details over long timescales. Our strategy is to use many short simulations to calculate the local diffusion tensor and drift velocities in the 2D reaction coordinate space predicted by the theory. Once this is complete, we can rapidly construct an ensemble of fibril growth trajectories. This approach is conceptually similar to the Markov State Models (MSM) used to simulate protein folding and aggregation30–36. In these models key states need to be identified from sampling strategies that provide sufficient coverage of the relevant conformational space. The risk to this approach is that the initial sampling may not be adequate to identify all the important states. In our approach the states are identified by the reaction coordinates defined in the theory. This approach invites the risk that key states are not resolved by the coarse-graining required by the theory. We mitigate this risk in two ways. First, by comparing the initial theory to experimental data, we achieve some assurance that unresolved states are not essential to the aggregation kinetics. Secondly, we can screen our simulations for states that fall outside of our reaction coordinate space. This screening revealed the existence of a bound state lacking H-bonds that is an important kinetic hub in aggregation.

In this paper we compute the aggregation kinetics of a fragment of the Alzheimer’s disease related molecule, amyloid β (Aβ)1, 37. Aβ16-22 is an excellent test system for our multi-scale algorithm because it is sufficiently small that it is possible to exhaustively sample the reaction rates. In addition, since the registry sampling time is exponentially dependent on the length of the molecules38, the small size of Aβ16-22 allows a direct comparison of the results of the MSM to unbiased simulations. Finally, aggregation kinetics have been experimentally measured for a variety of mutants revealing the non-trivial observation that the introduction of hydrophobic sidechains has a non-additive effect on aggregation kinetics. Our simulations show that the initial introduction of a hydrophobic sidechain helps to stabilize the aggregated state, but the subsequent addition of hydrophobic sidechains hinders growth by providing a disproportionate stabilization of mis-registered states.

Methods

Modeling fibril growth as a random walk in the H-bond space

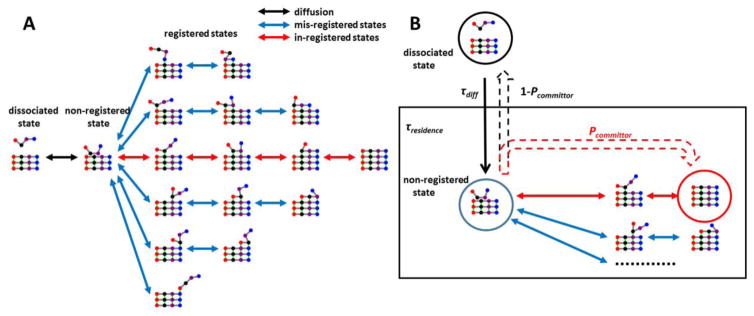

Our algorithm relies on a discretization of states according to the scheme illustrated in Fig. 1A. The main feature of this scheme is that binding states between incoming molecules and the fibril end are classified by 1) the alignment (registry) of H-bonds and 2) the number of bonds that have been formed. We also include two states outside of this ensemble of discrete binding states. These are the dissociated state and the “non-registered” state, which is an ensemble of loosely bound states where the incoming molecule makes nonspecific, sidechain mediated interactions with the fibril. This latter state was not included in the original theory28, but our simulations reveal the necessity of including at least one non-registered state. The non-registered state connects to all registry states with a single H-bond pair as well as the dissociated state (Fig. 1A). For each H-bonded state, there are 1–2 neighbor states that can be reached by breaking or forming a pair of H-bonds. We note that this definition of states easily maps to the Dock and Lock model of fibril growth.39 This model says that the initial contact of a molecule with the fibril results in a reversible “docked” state that will slowly convert to a (nearly) irreversible “locked” state.40 We identify the docked state with the ensemble of mis-registered bound states as well as the non-registered state that serves as the hub between registries. The system achieves the locked state when it finds the correct registry and rapidly forms the in-register H-bonds.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the random walk model of fibril growth. A) A peptide forms an initial contact with the fiber end in the non-registered state and then enters various registries by forming H-bonds. The dynamics of each registry can be described as a 1D random walk. B) Key kinetic parameters required for calculating the growth rate (Eq. 1).

In our algorithm a fibril growth attempt begins when a soluble peptide diffuses near the end of the fibril and forms an encounter complex. We assume that the encounter complex is part of the non-registered state, although this assumption is not important because the non-registered state will rapidly convert to a specific registry or back to the dissociated state and the rate limiting step for fibril growth is the slow exploration of different registries. The attempt ends when the molecule either falls off the end of the fibril or forms a full set of H-bonds in the correct registry (Fig. 1A, red pathway). During the growth attempt the molecule will randomly select registries by forming backbone H-bonds with the fibril (vertical direction in Fig. 1A) and perform a random walk in the H-bond space by forming or breaking H-bonds (horizontal direction in Fig. 1A). Each bidirectional arrow in Fig. 1A represents a pair of microscopic transition rates that can be measured from short MD simulations. These rates are then used to construct the MSM, which is used to generate long timescale trajectories of fibril growth. We note that, besides the random walk in horizontal direction (Fig. 1A), it is, in principle, possible that a peptide can shift from one registry directly into another without going through an intermediate non-registered state (vertical move in Fig. 1A). Analysis of the unrestrained MD trajectories (see Table 1) reveals that such transitions are very rare, accounting for only ~ 2% of those involving the intermediate non-registered state. Therefore, direct transitions between registries are not included in the current MSM model.

Table 1.

Summary of atomistic production simulations.

| Purpose | H-bond transitions around the anchoring pair | Transition times between H-bonded and non-H-bonded states | Lifetimes of each registry in the fully bound state |

| Peptides | Wild-type, CHA19, CHA20 and CHA1920 | Wild-type, CHA19, CHA20 and CHA1920 | Wild-type |

| Initial structures | Singly H-bonded register states | Singly H-bonded register states | Fully H-bonded register state |

| Restraints | Fibril core and the initial H-bond contact pair | Fibril core | Fibril core |

| Simulations | 50 ns × 50 (runs) × 50 (register states) | 50 ns × 50 (runs) × 50 (register states) | 100 ns × 100 (runs) × 8 (antiparallel registries) |

The growth rate of the fibril is determined by three timescales28 (Fig. 1B): the diffusion time for a free peptide to form the initial interactions (τdiff or 1/kdiff), the average residence time required for the non-registered state to evolve to either the fully bound or dissociated states (τresidence), and the average time required for a fully bound peptide to dissociate from the fibril end (τoff):

| (1) |

where Pcommittor is the probability that an incoming peptide becomes incorporated into the fibril in a fully-bound in-register state. Equation 1 assumes that the molecular attachment time is the sum of a diffusion time and time during which the molecule is exploring binding states with the fibril. The additional factor of Pcommittor accounts for the probability that the attachment attempt succeeds. We expect that this expression will be a reasonable description at low concentrations where binding attempts are sufficiently infrequent that they can be considered independent. The calculation of kgrowth in the current work consists two main steps: 1) enumerate all possible H-bond registry states and perform a series of short MD simulations to derive the average transition times between neighboring states, and 2) perform MSM simulations to calculate the kinetic parameters in Eq.1.

Enumeration of peptide H-bond registries and notation

In the current study, we focus on fibril growth of the wild type (sequence: K16LVFFAE22) and three mutated Aβ16-22 peptides, which have been shown to form fibrils consisting of antiparallel β-sheets.41–43 The H-bond registries accessible to Aβ16-22 peptides are illustrated in Fig. 2. The registry between the incoming peptide and the fibril core is defined by the peptide orientation, surface, and shift (Fig 2A). The orientation describes whether the incoming peptide is parallel or antiparallel to the template on the fibril end. The shift specifies the alignment of the incoming peptide relative to the template. As illustrated in Fig. 2B, a 0 shift indicates that the number of free residues on the N- and C- terminus for both the incoming and core peptides are no greater than one; a +2 shift value indicates either there are two or three unpaired residues in either the C-terminus of incoming peptides or the N-terminus of the core peptide; and a −2 shift value indicates there are two unpaired residues in the N-terminus of incoming peptides and C-terminus of the core peptide. Finally, due to the positioning of the backbone H-bonding groups within a β-strand, alternating amino acids are oriented correctly to form bonds with the template (Fig. 2A). We denote the “odd” (o) surface of the β-strand as the one where the backbone carbonyls and amide hydrogen atoms of the odd numbered amino acids are involved in H-bonds and the “even” (e) surface as the one where H-bonds are mediated by the even numbered residues. Note that the even/odd staggering also means that H-bonding groups on the incoming molecule are positioned in pairs that are highly correlated (Fig. 2A). Because of this, we parameterize our MSM model based on the formation and breakage of H-bond pairs rather than individual bonds.

Figure 2.

Schematic representations of backbone H-bond registries for Aβ16-22 fibrils. A) H-bonding network for 0 shift alignments in of Aβ16-22 β sheets. H-bonds are represented by dotted lines. The odd/even faces and orientation (antiparallel/parallel) of the incoming strand (S) and core peptide (C) are labeled. B: Schematic representations of all H-bond registries explicitly considered in this work. C: Example of two possible transitions of an incoming peptide with two H-bond pairs already formed (19–19 and 21–17; see main text for H-bond pair notations).

Taken together, we adopt a notation where each backbone H-bond registry is identified by the orientation of the incoming peptide, surfaces of the incoming and fibril core, and the shift. For example, “antiparallel e|e|0” denotes the in-register state where the incoming peptide docks using its even face to the even face of the fibril core in antiparallel orientation with 0 shift. This register allows four H-bonding pairs: 16–22, 18–20, 20–18 and 22–16 (see Fig. 2B, top row). This is one of two registries that are “in register”, the other is antiparallel o|o|0. Note that the existence of two in-register states is a consequence of the fact that Aβ16-22 forms antiparallel β-sheets.41 The more common case of fibrils composed of parallel β-sheets will result in a single in-register state that pairs an even surface to an odd surface.

Pilot simulations demonstrated that registries allowing two or fewer pairs of H-bonds had much shorter residence times and would not contribute significantly to τresidence. Therefore, these states were not included in the current model. In addition to the H-bonded states, we define two states without any H-bond pairs: if the minimum heavy atom distance between the incoming strand and fibril core peptides is no larger than 4.2 Å, the peptide is considered to be in the non-registered state; otherwise, the incoming strand is considered to have lost all contacts with the core and become fully dissociated.

Atomistic simulations and H-bond transition rate analysis

The program CHARMM44 was used to perform all MD simulations in the SASA implicit solvent model 45. A 2-fs time step was used, and a shift function with a cutoff at 7.5 Å was used for both the electrostatic and van der Waals terms (default for SASA).44 Unless otherwise stated, the temperature was kept constant by weak coupling to an external bath (at 300 K) with a coupling constant of 5.0 ps. SASA estimates the solvation free energy directly based on atomic solvent accessible surface areas and is highly efficient; yet it is accurate enough for folding of many small proteins, particularly β-sheets46. Specifically for Aβ16-22 fibrils, SASA simulations correctly recapitulate that the critical nucleus of fibril formation is likely a pentamer (see Fig. S1), and the fibril axial periodicity is ~30 nm. Both features are in agreement with existing theoretical and experimental data47–48. It has been shown that the Aβ16-22 sheets further assemble into bilayer or multilayers in solution24, 49. As such, the fibril core was represented as a bilayer β-sheet in the current study. The system consists of a small amyloid core with two incoming peptides on either end. The amyloid core was initially built as a bilayer structure with each layer containing 10 β-strands. The system was fully equilibrated in the SASA implicit solvent before the outer peptides on each end of both sheets were deleted to leave only 5 strands in each layer to represent the fibril core. The positions of all backbone heavy atoms in the core were harmonically restrained using a force constant of 1.0 kcal/mol/Å2.

For each registry (see Fig. 2B), two incoming stands were first docked on the core in fully H-bonded conformations (one on each end). The fully bound conformation was then used to generate 3 to 4 sets of structures where the incoming strands have just made the first pair of H-bond contacts with the fibril core in the corresponding registry. For example, three possible initial H-bond contact states may form for the antiparallel odd|odd|0 register state, between residues 17–21, 19–19 and 21–17, respectively (Fig. 2B). To generate these initial contact states, the backbone atoms on the incoming peptide involved in the selected H-bond contact pairs were harmonically restrained and the system was heated to 1000 K for 100 ps, during which the unrestrained portions of the incoming peptides become disordered. In this way, a total of 50 initial H-bond contact states were generated.

For each initial contact state, two sets of simulations were performed. In the first set the positions of backbone atoms of the core peptides and residues of the incoming peptide involved in the initial H-bond contact pair were harmonically restrained. This allowed focused sampling of H- bond transitions around the anchoring pair. In the second set, only the backbone heavy atoms of the fibril core were harmonically restrained. The incoming peptides could freely sample various bound and unbound states, allowing the transition times between various registries, the non-registered state, and the dissociated states to be derived. The above two sets of simulations were repeated for three mutant sequences in which phenylalanine residues at positions 19 and 20 are replaced with the non-natural amino acid cyclohexylalanine (CHA19, CHA20 and CHA1920). In addition, a third simulation set was performed for each antiparallel registry of the wild type peptide, where 100 simulations were initiated from fully H-bonded conformations lasting 100 ns each. These simulations yield the lifetimes of each registry in the fully bound state and provide a direct validation of the lifetimes predicted by the MSM model. A summary of all atomistic production simulations is given in Table 1.

Coordinates were saved every 5 ps and analyzed for transitions between H-bonding states. A transition involves either the formation or breakage of a pair of backbone H-bonds between an incoming peptide and the fibril core. For restrained simulations, the distances between amide hydrogen and carbonyl oxygen pairs (dH-O) were monitored for transitions. A backbone H-bond is considered formed when dH-O is shorter than 2.5 Å, and considered broken when dH-O exceeds 3.5 Å. In addition to the 1 Å gap in formation and breakage cutoff distances, a five-frame (that is, 25-ps) running average of dH-O was used to suppress spurious high-frequency fluctuations in the detection of H-bond transitions. An example of the H-bond transition analysis is shown in Fig. S2. For unrestrained simulations, the number of possible backbone H-bonds is too large to keep track of all possible dH-O distances. Instead, the running average was computed directly over the backbone H-bond states as identified using the COOR HBOND analysis module of CHARMM (1: H-bonded; 0: not H-bonded). A H-bond was considered formed when the average of its state is larger than 0.5 and broken when its average assigned state falls below 0.5. Note the distinct approaches for identifying H-bond transitions in the restrained and unrestrained simulations yield virtually identical results on selected trial trajectories. Transitions between H-bonded states and the nonspecific or dissociated state of the incoming peptides were also recorded from the unrestrained simulations.

Markov state model of fibril growth

Each H-bond registry can be divided into a series of states distinguished by the number of H-bonds formed. Upon formation of the initial H-bond contacts, H-bonds can form or break at the N- or C-terminus of the bounded peptides independently (e.g., see Fig. 2C). In principle, each H-bond pair can be considered unique. However, this will require much greater MD sampling in order to accumulate sufficient statistics on the transition rates. It was observed that the kinetics of H-bond transitions mainly depend on the orientation of the peptide (parallel vs. antiparallel), the nature of contacting residues, and the length of disordered peptide chains adjacent to the H-bond pair of interest. Specifically, we define the free chain length (FCL) as the number of dissociated residues of the incoming peptide starting from the N- or C-terminus and counting inwards until a H-bonded residue is encountered. Each possible H-bond transition can be then defined by peptide orientation, the initial and final FCLs together with the types of contacting residues. This classification allows the binning of similar transitions to improve the precision of the rates derived from atomistic simulations. Fig. 2C illustrates two possible transitions allowed for one of the sub-states of registry antiparallel e|e|0, starting from the state with two H-bond pairs (19–19 and 21–17). The “3 1 LEU:ALA” transition involves formation of a H-bond pair between LEU17 (incoming peptide) and ALA21 (core), where the numbers indicate a transition from a FCL of three amino acids to one amino acid. The “1 3 ALA:LEU” transition corresponds to breaking of the H-bond pair between ALA21 (incoming peptide) and LEU17 (core) resulting in an increase in FCL from one to three.. Examination of the transition time distributions of all H-bond pairs showed that they generally followed single exponentials very well (e.g., see Fig. S3), further supporting the appropriateness of grouping H-bond transitions as described above.

An overview of the MSM of Aβ16-22 fibril growth is illustrated in Fig. S4. The nonspecific state serves as a hub connecting all backbone H-bond registries as well as the disassociated state. As discussed below, transitions involving the nonspecific state also appear to follow a single exponential. As such, the Gillespie algorithm50 was employed in generating stochastic trajectories of fibril growth. Briefly, at each step, two random numbers in the interval [0, 1], R1 and R2, are generated and used to determine which transition will occur and the amount of time required. Given the rates k1, k2, …, kn for all possible transitions from the current state and the sum of these rates, ktot, transition i+1 is selected when

| (2) |

The second random number is set equal to the cumulative distribution function

| (3) |

to determine the time that elapses before transition i+1 occurs. Given that the probability function follows the single exponential distribution, the resulting explicit formula for this time is

| (4) |

The chosen state and elapsed time are appended to the trajectory, at which point the new set of accessible states is determined and the algorithm repeats.

Results and Discussions

Overview of H-bond transition rates

The average transition times of all H-bond pairs are summarized in Figs. 4 & S5 and Table S1. For both antiparallel and parallel orientations, the average times of H-bond formation are mainly influenced by FCL, with transitions at the terminal regions (FCL≤4) having much shorter timescales (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5A, top to bottom). This effect is attributed to the fact that a longer FCL requires larger portions of the chain to rearrange to form new bonds, an effect that likely saturates for suitably long FCL. The H-bond breakage time, in contrast, shows weaker FCL dependence (Fig. 4B and Fig. S5B), and appears to be mainly governed by nature of the contacting residue pair. For both single and double mutant peptides, replacement of PHE by CHA appear to lead to a mixture of increases and decreases in H-bond transition times. For example, PHE to CHA mutations lead to 40–80% increase of the transition time of 3 1 LEU:ALA with respect to the wild type peptide, but decreases the transition time of 4 2 PHE:VAL by 17–46%. However, there does not appear to be a clear pattern on how the individual H-bond transitions are affected by mutations that may be used directly to rationalize the observed effects of these mutations on fibril growth kinetics. Therefore, mutation effects on the fibril growth rate is unlikely to be explained by a few key interactions involving CHA. Instead, the impact of mutations on fibril growth is more likely to be attributed to an accumulation of small and mutually compensating effects, which collectively modulate various kinetic parameters in determining the net fibril growth rate (Eq. 1).

Figure 4.

Average backbone H-bond pair transition times associated with anti-parallel registries: A) H-bond pair formation, B) H-bond pair breakage, and C) transitions to the nonspecific state (i.e., breakage of the last H-bond pairs). All transition times in A and B were derived from the restrained simulations where a selected initial H-bond contact pair was harmonically restrained. The pairs are ordered such as that those with larger final FCLs are at the bottom. Transition times in C were derived from the non-restrained simulations where the incoming peptides were allowed to freely interact with the fibril core.

Transitions involving the nonspecific bound state

Our original analytic theory assumed that incoming molecules needed to completely dissociate from the fibril in order to change registries.28 However, inspection of preliminary MD trajectories revealed an ensemble of sidechain mediated, weakly associated states that appear to serve as a hub connecting various registries. A similar nonspecific bound state has also been shown to be important in other computational studies of protein aggregation.51–52 This state does not contain specific backbone H-bonds and its fluctuation and transitions cannot be directly enumerated by H-bonding patterns. Since the microscopic model predicts that the rate-limiting step of fibril growth is the sampling of different registries, the fluctuation within the nonspecific bound state is comparatively fast allowing it to be represented as a single state in the MSM. To test this assumption, we have further analyzed the nature of fluctuation and transitions in the nonspecific bound state from all the unrestrained simulations. The results are summarized in Fig. S6. There are a few key observations. First, transitions from the nonspecific bound state to the dissociated state or any H-bonded state appear to follow a single exponential. Second, the average transition time from the non-registered state to a new H-bonded state has minimal dependence on how different the new state is from the last H-bond pair broken upon entering the nonspecific state. The average transitions times of an incoming strand binding back to the origin H-bonding position, neighboring regions, and remote regions (greater than 2 residues away) are 0.3 ns, 0.7 ns, and 1.2 ns, respectively. We note that the average transition times may be skewed for occasional (and thus under-sampled) events where the peptide underwent extensive diffusion (tens of ns) on or near the fibril core surface before reforming H-bonds. Such events account for ~2–3% of transitions and are a by-product of the infinite dilution nature of the simulation setup. Fitting all curves to a single exponential yields similar lifetimes, supporting the inclusion of a single, uniform nonspecific bound state. Electron microscope images have also suggested the growing terminus of an Aβ16-22 fiber has at least 5 β-sheet monolayers, and the incoming peptides can diffuse rapidly between neighboring layers (the minimal fibril diameter is ~10 nm and the width of a peptide in extended conformation is less than 2 nm)49. The implication is that an incoming strand can migrate between neighboring sheets and all possible H-bond pairs have a similar probability to be formed when an incoming strand exits the non-registered state. On account of these observations, we use a single averaged time (732 ps) for all transitions from the nonspecific bound state to any singly H-bonded state in the MSM.

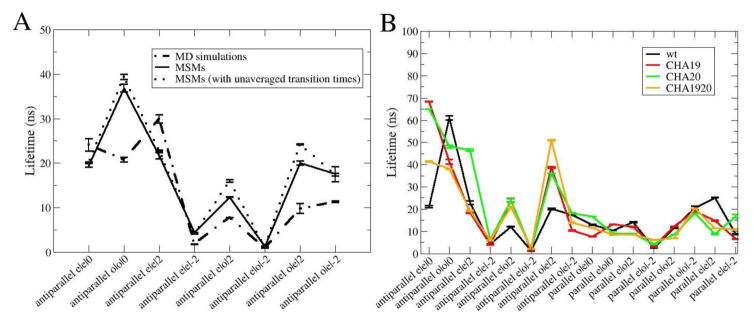

Validation of the MSM algorithm: impacts of mutation on register state lifetimes

The ability of the MSM to properly model fibril growth was first examined by comparing the calculated lifetimes of all fully H-bonded antiparallel registries with results derived directly from unrestrained atomistic simulations. This direct comparison is possible because of the efficiency of the SASA implicit solvent model. For each registry, 1000 MSM simulations were initiated from the fully H-bonded state and performed until all H-bond pairs were broken. Because the corresponding atomistic simulations lasted 100 ns each (see Methods), only MSM and MD trajectories that arrived at the nonspecific bound state within 100 ns were included in calculating the averages summarized in Fig. 5A. The results confirm that lifetimes predicted by MSM (solid trace) and MD (dashed trace) are highly consistent, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of R = 0.74. Importantly, the lifetimes derived from MD and MSMs also follow similar distributions (Fig. S7). Curiously, the MSM predicts significantly longer lifetimes for two registries, “antiparallel e|o|0” and “antiparallel o|e|2”. Closer inspection of the atomistic trajectories suggest that there is some level of cooperativity in H-bond transitions involving neighboring residues, which is not included in the current MSM. Cooperativity of H-bond transitions in principle could be included in a next-generation MSM of fibril growth, but this was not investigated further in this work given the reasonable agreement between MD and MSM for most states. We also investigated whether binning of transitions by residue type and FCL could be masking nonlocal effects (e.g. neighboring residue dependence). To examine if this could lead to significant discrepancy in predicted lifetimes, we reconstructed the MSM by treating each H-bond pair to be unique, i.e., defined by the peptide orientation and residue numbers of the contacting pair. As shown in Fig. 5A, lifetimes derived from this model (dotted line) are essentially identical to results derived from the MSM with H-bonding transition classification, suggesting that perturbations from neighboring amino acids are relatively insignificant.

Figure 5.

Average lifetimes of fully H-bonded registries. A) MD vs. MSM results for antiparallel registries of the wild-type peptide. Two MSM models are considered with and without equivalent H-bond transition binning. B) MSM lifetimes of the wild type and three mutant peptides for all registries considered.

The effects of PHE to CHA mutations on the registry lifetimes are summarized in Fig. 5B. Interestingly, the CHA mutations are often non-additive with the double mutation showing a smaller perturbation relative to the WT that one or both of the single mutants. This is a nontrivial prediction that appears consistent with the experimental measurements of fibril growth kinetics49. Inspection of Fig. 5B shows that it does not appear possible to explain the effects of mutations on the overall fibril growth kinetics based on the lifetime change of one or a few individual registries. Instead, it seems necessary to examine the full ensemble of MSM trajectories of how the peptide may sample various registries before either becoming fully incorporated into the fibril core or falling back into solution.

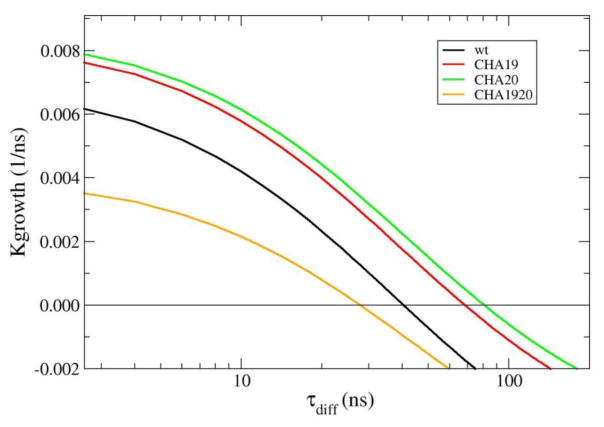

Net fibril growth rates and effects of mutations

To calculate τresidence and Pcommittor (eq. 1), 20000 MSM simulations were performed with 10000 each on the even and odd faces of the fibril core. Each simulation was initiated from the nonspecific state and terminated when the incoming strand reached the antiparallel fully H-bonded in-register state or the dissociated state. Pcommittor was calculated as the probability of MSM trajectories reaching the fully H-bonded in-register state, and τresidence is the average length of all trajectories (Fig, 1B). To calculate τoff, another set of 20000 MSM simulations was initiated from the antiparallel in-register fully bound state and performed until the strand fully dissociated from the fibril core. The results are summarized in Table 2. On average, the peptide samples ~14 or ~24 transitions between the nonspecific and H-bonded registries during a single association or dissociation process, respectively. The calculated τresidence and τoff thus cannot be directly related to the lifetime of any specific registry. Compared with the wild type peptide, the single mutations CHA19 and CHA20 significantly increase τoff with smaller effects on Pcommittor or τresidence, suggesting a net effect of preferentially stabilizing the fibril state. The double mutation CHA1920, in the contrast, has higher τresidence, smaller Pcommittor but similar τoff with respect to the wild type peptide, indicating a broader stabilization of both in-register and off-register states. Kinetic parameters summarized in Table 2 allow one to calculate how the fibril net growth rate depends on the peptide concentration, which is inversely related to τdiff. We note that the timescales calculated from implicit solvent simulations without realistic solvent friction can be only considered relative. These timescales thus can not be directly compared with experimental results and we mainly focus on how the growth kinetics depend on concentration and the affect of mutations. The results, shown in Fig. 6, show that both CHA19 and CHA20 mutations increase the net fiber growth rate, with CHA20 having a slightly stronger effect. However, when both mutations are introduced, they actually reduce the growth kinetics, except at very low concentrations (or large τdiff). These general trends of fibril growth kinetics are fully consistent with experimental results49, even though the negative impacts of the double mutation on growth rate appear overestimated. The reason for the overestimation is not entirely clear, though it is likely due to limitations of the protein force field employed.

Table 2.

Key kinetic parameters of fiber growth derived from MSM.

| wt | CHA19 | CHA20 | CHA1920 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pcommittor | 0.50±0.01 | 0.53±0.01 | 0.55±0.01 | 0.46±0.01 |

| τresidence (ns) | 36.8±4.8 | 39.8±2.43 | 42.8±11.6 | 44.4±11.8 |

| τoff (ns) | 154.5±23.2 | 205.7±42.7 | 224.1±65.0 | 154.8±27.7 |

Figure 6.

Predicted net growth rate of Aβ16-22 fibril as a function of the peptide concentration as reflected in the diffusion time (concentration ∝ τdiff). The growth rates were calculated using Eq. 1 with parameters listed in Table 2.

To further investigate the molecular origin of the predicted growth kinetic effects, the influence of mutations on the residence time of each registry during the association/dissociation processes was investigated. As summarized in Fig. 7A and B, the average time the peptide spends searching through various H-bonding combinations within the in-register states (antiparallel even|even|0 and antiparallel odd|odd|0) only account for small portions of the total association times (2% and 1%, respectively). The association process is dominated by the need to sample a large number of incorrect registries. The time spent on mis-registered states is likely the origin of the slow “incorrect docking” step observed in recent simulations of another amyloid-forming peptide TTR105-115.30 Once the correct registry is found, the process of zipping up the in-register H-bond pairs is very fast. This is also supported by the observation that the in-register states have the longest residence times of all the registries in the dissociation process (Fig. 7C–D and Table S2). Importantly, the peptide reforms the fully bound in-register states numerous times during the disassociation process. The singly mutated peptides display much stronger tendency of reforming the fully bound in-register state, averaging ~92 and ~75 times during the disassociation process for CHA19 and CHA20 peptides, respectively, compared ~42 times for the wild-type peptide. In contrast, the double mutant CHA1920 dissociates with the fewest times (~39) of reforming the fully bound in-register state.

Figure 7.

Graph summary of Aβ16-22 fibril association and dissociation pathways for the wild-type peptide and three mutants. Panels A) and B) are derived from MSM trajectories of growth on the even (A) and odd (B) faces of the fibril, initiated from the non-register state. Panels C) and D) are derived from MSM trajectories of peptide disassociation from fully H-bonded in-register state on the even (C) and odd (D) faces of the fibril. The nodes are colored according to register state types (Non-registered: yellow; parallel: green; antiparallel and mis-register: blue; antiparallel and in-register: red). The node size is set based on the relative residence time of the state with respect to that of the non-register state (which is set to a constant size), and the edge thickness corresponds to the number of transitions in/out of the state.

The availability of the ensemble of MSM trajectories allows further analysis to identify one or a few (mis)-registries or even specific H-bond transitions within a given registry branch that may potentially account for a majority of the kinetic effects of various mutants. It is important to note that identification of such key registries or H-bond transitions can only be reliably done within the context of the whole MSM network and would not be possible given the raw data alone (e.g., Figs. 4 and 5). Mutation-induced changes in the overall growth rate are largely attributed to the impacts on τoff. For both single mutations CHA19 and CHA20, larger τoff can be more directly attributed to increased residence times of the in-register antiparallel even|even|0 state, by 159 ns and 112 ns with respect to the wild peptide for CHA19 and CHA20, respectively (see Table S2). Fig. S8 summarizes the transitions between various H-bonding configurations within the two in-registries (antiparallel e|e|0 andantiparallel o|o|0). It reveals that the bottleneck for dissociation from the fully bound antiparallel even|even|0 registry is the breakage of the second H-bond pair after losing the terminal LYS16:GLU22 or GLU22:LYS16 interactions. In other words, the terminal H-bond pair has a strong tendency to quickly reform, preventing further unzipping of H-bonds. CHA mutations of PHE19 or PHE20 results strongly enforce this tendency (red circle, Fig S8A), while the double mutant has minimal impact. In contrast, transitions within the other in-register state, antiparallel odd|odd|0, do not depend strongly on any of the three mutations. In the association process, the main effect of the double mutation was found to be on the residence time of the mis-register states, with the largest increases observed on the residence time of the antiparallel odd|even|2 registry (see Fig. S9).

Conclusion

Unlike the folding of proteins to the native state, pathogenic aggregates are not subject to an evolutionary pressure to develop efficient folding pathways. As a result, aggregation requires a search over a large configuration space with a relatively flat free energy.26 This means that aggregation involves a blind search over states comparable to the Levinthal paradox. Here we report a method to efficiently sample this space and generate an ensemble of growth trajectories. This method relies on the assumption that the aggregation process can be projected onto two order parameters; the number of H-bonds and the molecular alignment. This, of course, is an approximation and the method is successful because states that lie outside of this reaction space are usually not kinetically relevant. That is, the system spends most of its time forming and breaking non-productive H-bonds and states that are not described by the H-bond and registry reaction coordinates are not populated long enough to significantly affect the reaction time. Still, these states can have significant effects if they serve as important gateways to long-lived states. This was the case with the non-registered state reported here and the future success of this method will depend on the ability to identify and sample these gateway states.

In this work, we looked at the effect of hydrophobic mutations. Naively, one might expect these mutations to monotonically stabilize the fibril. In fact, we find the effects are much more subtle because the new sidechains have unpredictable effects on bond formation and breakage rates throughout the reaction space. Thus, mutations that enhance the stability can do so by some combination of removing kinetic traps in the search over mis-registered states (enhancing the on-rate), or by strengthening the bonds within the in-register state (reducing the off-rate). A third possibility, which was less significant in the present work, is that a mutation biases trajectories toward the aggregated state (increasing Pcommittor). Each of these contributions is a function of many microscopic rate constants, which highlights the need to efficiently sample the reaction space.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Front (left) and side views (right) of an initial structure of the antiparallel e|e|0 registry containing a pair of initial H-bond contacts between LYS16 and GLU22. The peptides are shown in cartoon representations with the fibril core colored in green and incoming peptides in purple. The backbone is shown in line representation and the initial H-bonds as red sticks.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (GM107487). Part of the computing for this project was performed on the Beocat Research Cluster at Kansas State University. Computer resources was also used at Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) facilities (TG-MCB150008). This work is contribution number 17-004-J from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

References

- 1.Morriss-Andrews A, Shea J-E. Computational studies of protein aggregation: Methods and applications. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2015;66(1):643–666. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040513-103738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler DM, Koulov AV, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Functional amyloid – from bacteria to humans. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2007;32(5):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(2):101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirkitadze MD, Bitan G, Teplow DB. Paradigm shifts in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders: The emerging role of oligomeric assemblies. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2002;69(5):567–577. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silveira JR, Raymond GJ, Hughson AG, Race RE, Sim VL, Hayes SF, Caughey B. The most infectious prion protein particles. Nature. 2005;437(7056):257–261. doi: 10.1038/nature03989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lührs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Döbeli H, Schubert D, Riek R. 3D structure of Alzheimer’s amyloid-β(1–42) fibrils. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(48):17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao Y, Ma B, McElheny D, Parthasarathy S, Long F, Hoshi M, Nussinov R, Ishii Y. Aβ(1-42) fibril structure illuminates self-recognition and replication of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(6):499–505. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu L, Tran J, Jiang L, Guo Z. A new structural model of Alzheimer’s Aβ42 fibrils based on electron paramagnetic resonance data and Rosetta modeling. Journal of Structural Biology. 2016;194(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed M, Davis J, Aucoin D, Sato T, Ahuja S, Aimoto S, Elliott JI, Van Nostrand WE, Smith SO. Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-[beta]1-42 oligomers to fibrils. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(5):561–567. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petkova AT, Yau W-M, Tycko R. Experimental constraints on quaternary structure in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry. 2006;45(2):498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu J-X, Qiang W, Yau W-M, Schwieters Charles D, Meredith Stephen C, Tycko R. Molecular structure of β-Amyloid fibrils in Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Cell. 2013;154(6):1257–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertini I, Gonnelli L, Luchinat C, Mao J, Nesi A. A new structural model of Aβ40 fibrils. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(40):16013–16022. doi: 10.1021/ja2035859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko R. A structural model for Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(26):16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2006;75(1):333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma B, Nussinov R. Simulations as analytical tools to understand protein aggregation and predict amyloid conformation. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2006;10(5):445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Toward a molecular theory of early and late events in monomer to amyloid fibril formation. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2011;62(1):437–463. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu C, Shea J-E. Coarse-grained models for protein aggregation. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2011;21(2):209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ban T, Hoshino M, Takahashi S, Hamada D, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Goto Y. Direct observation of Aβ amyloid fibril growth and inhibition. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;344(3):757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knowles TPJ, Shu W, Devlin GL, Meehan S, Auer S, Dobson CM, Welland ME. Kinetics and thermodynamics of amyloid formation from direct measurements of fluctuations in fibril mass. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(24):10016–10021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610659104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen HD, Hall CK. Molecular dynamics simulations of spontaneous fibril formation by random-coil peptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(46):16180–16185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407273101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auer S, Meersman F, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. A generic mechanism of emergence of amyloid protofilaments from disordered oligomeric aggregates. PLOS Computational Biology. 2008;4(11):e1000222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricchiuto P, Brukhno AV, Auer S. Protein aggregation: Kinetics versus thermodynamics. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2012;116(18):5384–5390. doi: 10.1021/jp302797c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheon M, Chang I, Hall Carol K. Spontaneous formation of twisted Aβ16-22 fibrils in large-scale molecular-dynamics simulations. Biophysical Journal. 2011;101(10):2493–2501. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheon M, Chang I, Hall CK. Extending the PRIME model for protein aggregation to all 20 amino acids. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2010;78(14):2950–2960. doi: 10.1002/prot.22817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dill KA, Chan HS. From Levinthal to pathways to funnels. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 1997;4(1):10–19. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2004;14(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmit JD. Kinetic theory of amyloid fibril templating. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2013;138(18):185102. doi: 10.1063/1.4803658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dill KA, Chan HS. From Levinthal to pathways to funnels. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4(1):10–9. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schor M, Mey ASJS, Noé F, MacPhee CE. Shedding light on the Dock–Lock mechanism in amyloid fibril growth using Markov State Models. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2015;6(6):1076–1081. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barz B, Wales DJ, Strodel B. A Kinetic approach to the sequence–Aggregation relationship in disease-related protein assembly. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2014;118(4):1003–1011. doi: 10.1021/jp412648u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lane TJ, Shukla D, Beauchamp KA, Pande VS. To milliseconds and beyond: challenges in the simulation of protein folding. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2013;23(1):58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senne M, Trendelkamp-Schroer B, Mey ASJS, Schütte C, Noé F. EMMA: A software package for Markov model building and analysis. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2012;8(7):2223–2238. doi: 10.1021/ct300274u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pande VS, Beauchamp K, Bowman GR. Everything you wanted to know about Markov State Models but were afraid to ask. Methods. 2010;52(1):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chodera JD, Noé F. Markov state models of biomolecular conformational dynamics. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2014;25:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowman GR, Huang X, Pande VS. Using generalized ensemble simulations and Markov state models to identify conformational states. Methods. 2009;49(2):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenwald J, Riek R. Biology of amyloid: Structure, function, and regulation. Structure. 2010;18(10):1244–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmit J. Kinetic theory of amyloid fibril templating. J Chem Phys. 2013;138:185102. doi: 10.1063/1.4803658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esler WP, Stimson ER, Jennings JM, Vinters HV, Ghilardi JR, Lee JP, Mantyh PW, Maggio JE. Alzheimer’s disease amyloid propagation by a template-dependent dock-lock mechanism. Biochemistry. 2000;39(21):6288–6295. doi: 10.1021/bi992933h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen PH, Li MS, Stock G, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Monomer adds to preformed structured oligomers of Aβ-peptides by a two-stage dock–lock mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(1):111–116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607440104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balbach JJ, Ishii Y, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Rizzo NW, Dyda F, Reed J, Tycko R. Amyloid fibril formation by Aβ16-22, a seven-residue fragment of the Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide, and structural characterization by solid state NMR. Biochemistry. 2000;39(45):13748–13759. doi: 10.1021/bi0011330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehta AK, Lu K, Childers WS, Liang Y, Dublin SN, Dong J, Snyder JP, Pingali SV, Thiyagarajan P, Lynn DG. Facial symmetry in protein self-assembly. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130(30):9829–9835. doi: 10.1021/ja801511n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petkova AT, Buntkowsky G, Dyda F, Leapman RD, Yau WM, Tycko R. Solid state NMR reveals a pH-dependent antiparallel β-sheet registry in fibrils formed by a β-amyloid peptide. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;335(1):247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1983;4(2):187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrara P, Apostolakis J, Caflisch A. Evaluation of a fast implicit solvent model for molecular dynamics simulations. Proteins. 2002;46(1):24–33. doi: 10.1002/prot.10001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gfeller D, De Los Rios P, Caflisch A, Rao F. Complex network analysis of free-energy landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(6):1817–1822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608099104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldsbury CS, Wirtz S, Müller SA, Sunderji S, Wicki P, Aebi U, Frey P. Studies on the in Vitro Assembly of Aβ 1–40: Implications for the Search for Aβ Fibril Formation Inhibitors. J Struct Biol. 2000;130(2–3):217–231. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hills RD, Brooks CL. Hydrophobic cooperativity as a mechanism for amyloid nucleation. J Mol Biol. 2007;368(3):894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senguen FT, Lee NR, Gu X, Ryan DM, Doran TM, Anderson EA, Nilsson BL. Probing aromatic, hydrophobic, and steric effects on the self-assembly of an amyloid-β fragment peptide. Molecular BioSystems. 2011;7(2):486–496. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00080a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gillespie DT. Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1977;81(25):2340–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Šarić A, Chebaro YC, Knowles TPJ, Frenkel D. Crucial role of nonspecific interactions in amyloid nucleation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(50):17869–17874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410159111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller Y, Ma B, Nussinov R. Polymorphism in Alzheimer Aβ amyloid organization reflects conformational selection in a rugged energy landscape. Chemical Reviews. 2010;110(8):4820–4838. doi: 10.1021/cr900377t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.