Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate relationships among cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric/psychosocial measures assessed in a multicenter cohort of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Methods:

Recently diagnosed patients with definite or probable ALS diagnosis were administered 7 standardized psychiatric/psychosocial measures, including the Patient Health Questionnaire for diagnosis of depression and elicitation of wish to die. The Cognitive Behavioral Screen was used to classify both cognitive and behavioral impairment (emotional-interpersonal function). An ALS version of the Frontal Behavioral Inventory and Mini-Mental State Examination were also administered.

Results:

Of 247 patients included, 79 patients (32%) had neither cognitive nor behavioral impairment, 100 (40%) had cognitive impairment, 23 (9%) had behavioral impairment, and 45 (18%) had comorbid cognitive and behavioral decline. Cognitive impairment, when present, was in the mild range for 90% and severe for 10%. Thirty-one patients (12%) had a major or minor depressive disorder (DSM-IV criteria). Cognitive impairment was unrelated to all psychiatric/psychosocial measures. In contrast, patients with behavioral impairment reported more depressive symptoms, greater hopelessness, negative mood, and more negative feedback from spouse or caregiver. A wish to die was unrelated to either cognitive or behavioral impairment.

Conclusions:

While we found no association between cognitive impairment and depression or any measure of distress, behavioral impairment was strongly associated with depressive symptoms and diagnoses although seldom addressed by clinicians. Thoughts about ending life were unrelated to either cognitive or behavioral changes, a finding useful to consider in the context of policy debate about physician-assisted death.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between cognitive-behavioral and psychiatric/psychosocial characteristics observed at baseline for 355 patients in the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Multicenter Cohort Study of Oxidative Stress (COSMOS1). While an association between cognitive deficits and depression repeatedly has been shown for patients with cognitive decline in late life,2,3 and medically healthy patients with depression,4,5 little is known about such an association for patients with ALS.

The COSMOS included 4 areas of inquiry: environmental exposures, dietary habits, cognitive-behavioral, and psychiatric/psychosocial features. Results from the cognitive and psychiatric/psychosocial baseline data of COSMOS,6,7 previously published separately, are integrated in the current analysis. We6 had found that 60% of patients had mild to moderate executive functioning impairment on a short screening battery, somewhat higher than reported elsewhere,8–10 while on behavioral measures (emotional-interpersonal function), 30% had mild or moderate impairment,5 consistent with other reports.8,11 Of 247 patients with complete data on the ALS–Cognitive Behavioral Screen (CBS), 50 (20%) showed impairment on both cognitive and behavioral measures. Those with behavioral problems were more likely to have cognitive deficits.

In contrast, we7 found that only 12% of COSMOS patients had a clinical depressive disorder, including 7% with minor depression and 5% with major depression, consistent with prior findings.12–15 Of the 62 patients (19%) who expressed a wish to die, only 23 (37%) were clinically depressed.

METHODS

Research questions.

Based on prior findings, we sought to address these questions: (1) Are depression rates elevated among patients with cognitive impairment? (2) Are depression rates elevated among patients with behavioral impairment? (3) Conversely, do depressed patients have more cognitive and/or behavioral impairment than those without depression? and (4) Is wish to die, reported by 19% of the sample in the depression study, related either to cognitive or behavioral impairment, and are patients with intact cognitive function more likely to express such a wish? We include measures of depression, and also psychosocial ratings of quality of life, hopelessness, positive and negative mood, and level of partner support.

Sample.

Sample size was determined for the environmental exposure component of the COSMOS. Sixteen geographically distributed study sites enrolled patients between January 2010 and April 2013. Recruitment numbers ranged from <10 to >100 per study site. Eligibility criteria included a definite, probable, or possible ALS diagnosis according to the El Escorial/Airlie House revision16 with the addition of the Awaji criteria to increase the chance of early diagnosis.17 In addition to being willing to return to the study site for follow-up visits, the patient had to have a reliable family caregiver who also consented to a structured interview. Exclusion criteria included familial ALS based on a clear history of disease in first-degree relatives or a positive familial ALS molecular test result such as SODI or C9 or f72 mutations, major neurologic disease other than ALS, and any unstable medical conditions requiring treatment. More detailed descriptions of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, study rationale, design, power calculations, and measures are presented elsewhere.1 Patients, who were potentially eligible, were asked during routine clinic visits if they would like to participate after the study was described.

Standardized assessments.

The following measures were administered: sociodemographic queries, the ALS Functional Rating Scale–Revised and forced vital capacity, 7 psychiatric-psychosocial measures including the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9), a widely used screen for depressive disorders that generates both a diagnostic category according to DSM-IV18 and DSM-5,19 and a depression severity rating.20 The PHQ also includes an item, “thoughts that you'd be better off dead/thoughts about ending your life,” which we used separately in some analyses of Wish to Die. Other ratings assess hopelessness, stress, quality of life, partner support, and a set of 12 visual analog scales (VAS).21–26 Measures of executive function and behavioral impairment include the ALS-CBS27 and the ALS–Frontal Behavioral Inventory (FBI).28 The cognitive tests were selected to assess executive function and select language skills because the ALS variant of dementia is known to be of the frontotemporal lobar dementia subtype. The consensus criteria of Strong29 was used to classify impairment as absent, mild, or moderate. We included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)30 because it is the standard screen for cognitive impairment in psychiatry and geriatrics. A description of the measures is provided in table e-1 at Neurology.org, including number of items, contents, score range, and cutoffs (where applicable).

Procedures.

Telephone interviews were conducted by trained interviewers at Columbia. Psychological scales were sent to the patients in advance via mail to prepare them for the interviews. Neuropsychological assessments were conducted at each study site by trained raters.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The coordinating site institutional review board (Columbia University, New York) and each of the local institutional review boards approved the study protocol, and all participants gave informed consent.

Data analysis.

The Data Coordinating Center at Columbia managed all data. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Demographic data across various groups were analyzed using either the t test for continuous variables or analysis of variance procedures for categorical variables, dependent on grouping measures. Psychological measures were compared in those with and without impairment using analysis of covariance, controlling for an a priori set of covariates including age, sex, duration of ALS-related symptoms, education, race, and ethnicity. Cognitive and behavioral continuous measures were examined across PHQ Depression diagnoses using analysis of covariance procedures controlling for the same set of covariates.

Cognitive impairment classification is based on the Cognitive subscale scores on the ALS-CBS (see table 1). Hereafter, for the sake of brevity, we use the nomenclature “none,” “minor,” and “moderate” to indicate patients with no cognitive or behavioral impairment, respectively. We do not add the modifier “executive function” every time we use the term “cognitive.” Depression diagnosis using DSM-IV was determined by the PHQ-9.20 The subgroups of minor and major depression were combined because there were so few cases of major depression (total n = 16).

Table 1.

Total sample: Demographic and disease characteristics at study baseline (n = 253)

As stated in our earlier publication using this dataset7: “The same procedures were applied to compare the patients grouped by the 4 response options to the PHQ queries about ‘wish to die.’ When we modified the original PHQ item, ‘thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way’ by separating the component parts into passive thoughts (‘better off dead’) and active thoughts (revised to state, ‘thoughts about ending your life’), we had expected that patients who endorsed the latter would have higher rates of depression, but we found identical rates. We therefore included all patients who endorsed either one or both components, and in calculating severity, used the component with the higher score (greater frequency of thoughts). When comparing PHQ total scores for the four response options on the ‘wish to die’ item, we used a modified total PHQ score excluding the ‘wish to die’ item and pro-rating items included in the total score. Because of the multiple analyses conducted, we use p < 0.01 to signify statistical significance.”

RESULTS

Sample.

The ALS COSMOS enrolled 355 patients. Another 477 potentially eligible patients declined participation. They did not differ from the 355 enrolled patients according to demographic characteristics, disease duration, and El Escorial Criteria diagnostic groups. Patients with complete data on both psychiatric/psychosocial and cognitive/behavioral measures constitute the current sample of 247. Of these, 79 patients (32%) had neither cognitive nor behavioral impairment (using ALS-CBS criteria), 100 (40.5%) had only cognitive impairment, 23 (9.1%) had only behavioral impairment, and 45 (18%) showed impairment on both cognitive and behavioral measures.

Demographic and medical characteristics are shown in table 1. Overall, the participants were predominantly white, well educated, and had health insurance. One-third were still working at study entry, and the clinical measures indicate generally early disease, not unexpected as recruitment was performed at or shortly after diagnosis.

Association between cognitive impairment and depression/distress.

Are patients with cognitive impairment more likely to be depressed?

As shown in table 2, cognitive impairment level (none, minor, moderate) was unrelated to a diagnosis of depression or any other measure of distress (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [PANAS] negative mood, hopelessness, stress [Global Assessment of Recent Stress], or quality of life). None of the 12 VAS instruments differed between groups. However, the groups did differ in amount of both positive (supportive, encouraging) and negative (critical or avoidant) partner responses on the Manne Scale as reported by patients. While the pattern for positive support across groups is not linear and the differences are modest, there is a stronger association with negative support.

Table 2.

Associations among patient characteristics, psychological measures, and ALSci criteria and FTLDa

The ALS-CBS Cognitive subscale and the MMSE were correlated (ρ = 0.317, p < 0.001, Pearson r = 322, p < 0.001 [n = 235]), despite the attenuated range of the latter. In addition, patients with cognitive impairment had lower MMSE scores than patients without cognitive impairment measured by the ALS-CBS.

Association between behavioral impairment and depression.

Are patients with behavioral impairment more likely to be depressed?

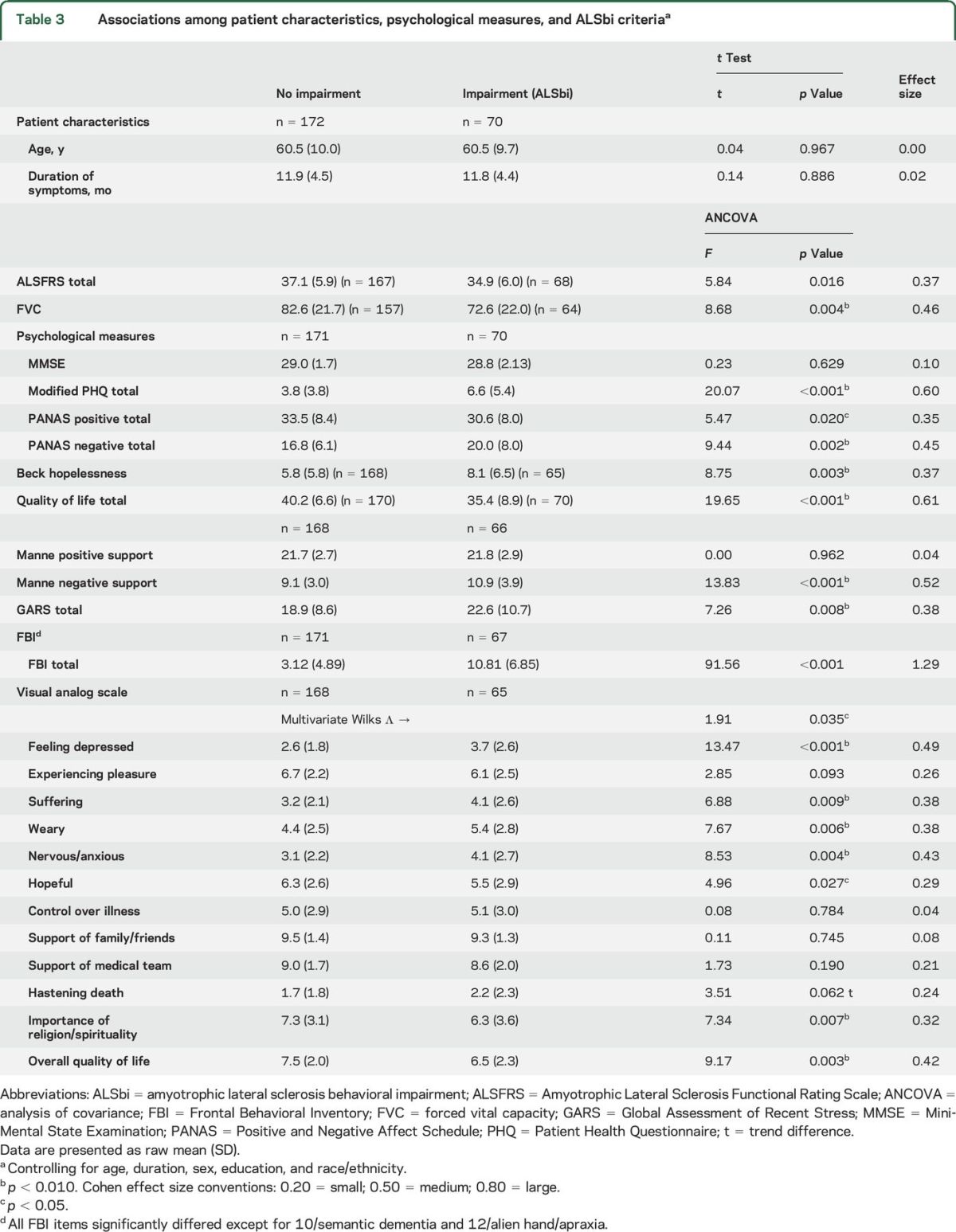

Table 3 shows considerable and consistent associations among disease characteristics, behavioral measures, and depression, albeit with moderate effect sizes. Patients with behavioral impairment were more likely to have depressive symptoms, lower levels of positive affect and higher levels of negative affect, higher mean scores on measures of hopelessness, lower quality of life, and higher stress levels. On VAS instruments, patients with behavioral impairment had higher scores on the dimensions of suffering, anxiety, and weariness, and were less hopeful than patients without behavioral impairment. In addition, depressed patients had higher scores (more behavioral impairment) on the FBI-ALS.

Table 3.

Associations among patient characteristics, psychological measures, and ALSbi criteriaa

There was no relationship between our behavioral measure of impairment and the MMSE: ρ = 0.080, p = 0.227 (n = 230); Pearson r = 0.071, p = 0.287 (n = 230).

Association between depression and cognitive and/or behavioral impairment.

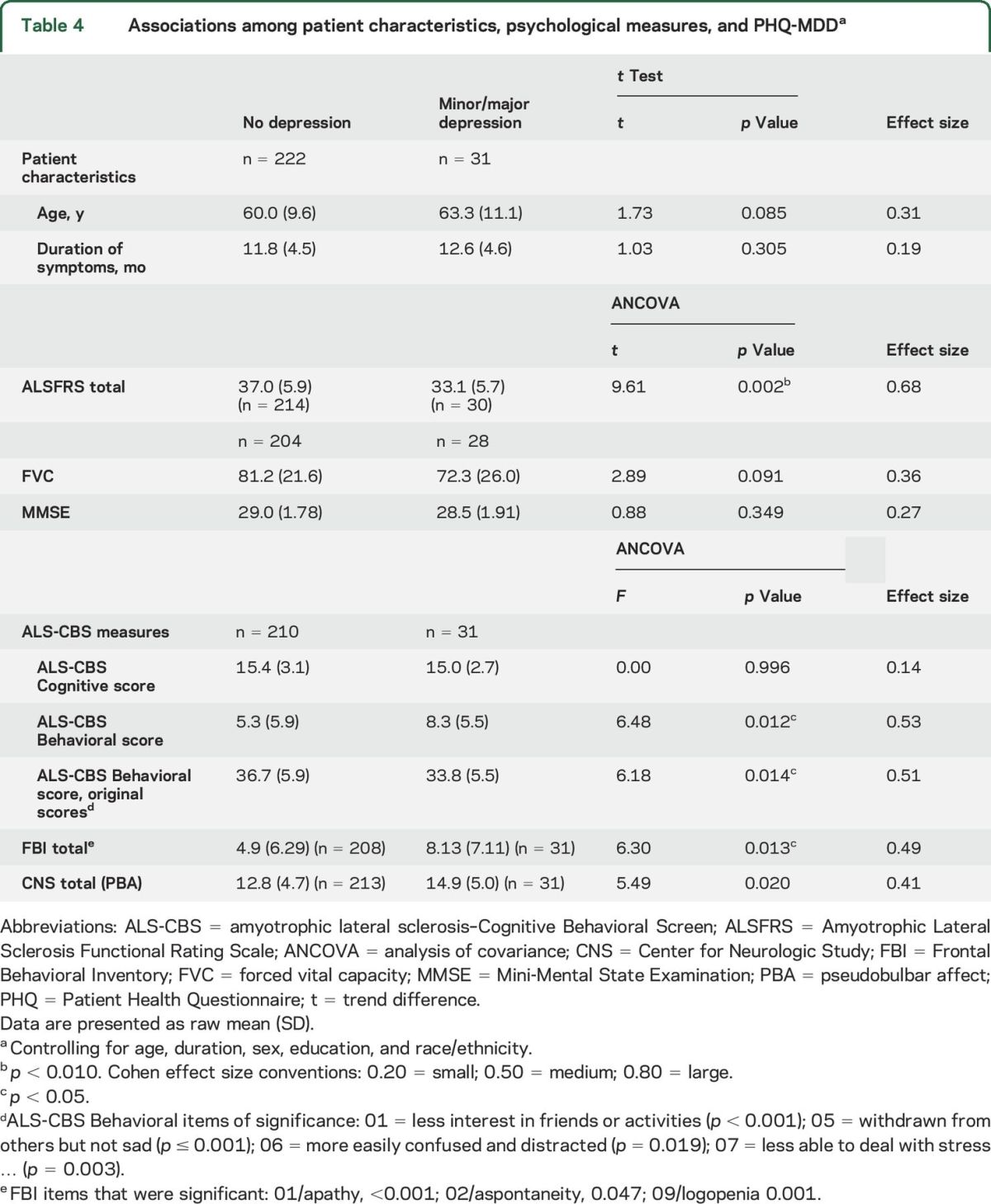

Total means on the subscales of the CBS were compared for patients with and without depression (table 4). Although patients with depression did not differ from those without depression on the Cognitive subscale (p = 0.996), behavioral impairment and depression (ALS-CBS Behavioral subscale) were associated with each other (p = 0.012), and FBI-ALS (p = 0.013). MMSE scores did not differ between those with or without depression.

Table 4.

Associations among patient characteristics, psychological measures, and PHQ-MDDa

Analyses with 4 patient groups.

We repeated the above comparisons using 4 groups of patients: group 1 = no impairment (n = 79); group 2 = cognitive impairment only (n = 99); group 3 = behavioral impairment only (n = 23); and group 4 = both cognitive and behavioral impairment (n = 45). After control for age, duration, sex, education, and race/ethnicity, groups 1 and 2 had lower PHQ scores (were less depressed) than groups 3 and 4 (df = 3,236; F = 7.41, p < 0.001, data not shown). In general, less distress was found for patients with either no impairment or only cognitive impairment; these measures included negative affect (PANAS), hopelessness, quality of life, partner support, and the VAS instruments of depressed mood, weariness, and anxiety.

What is the association between wish to die and cognitive or behavioral impairment?

Frequency of wish to die was classified as absent, several days per week, or more than half the days per week. No associations were found between caregiver ratings of depression in patients and our classification of mild or moderate cognitive or behavioral impairment (data not shown). Thoughts about ending life or being better off dead seem unrelated to either cognitive or behavioral changes associated with ALS as measured here, including the MMSE. We then examined the relationship between patients' thoughts about ending their life, and caregiver ratings of the patients' depression as well as with the patients' own ratings of their depression on the PHQ scale. Caregiver–patient agreement is statistically significant in both comparisons but in the “fair” range of agreement using the κ statistic. Thus, when patients reported minor or major depression, 40% (12/30) of the time, the caregiver said the patient was not depressed.

DISCUSSION

When depression ratings were examined for patients with and without behavioral impairment (CBS Behavioral subscale), nearly all psychiatric/psychosocial measures differed: patients with behavioral impairment experienced more depression, lower scores on positive mood and higher scores on negative mood, more hopelessness, more negative partner support, more stress, and lower quality of life. The consistency of these findings is noteworthy. Similarly, the other measure of behavioral impairment, the FBI-ALS, was also associated with depression. The causal direction, however, is not clear in this cross-sectional assessment.

Across numerous comparisons, we found no relationship between the CBS or MMSE measures of cognitive impairment, and any measure of depression, distress, or wish to die. The one exception is the Criticism subscale of the Manne Scale of Partner Support. Items on this subscale include these: “did not seem to respect my feelings”; “criticized the way I handle my disease.” Cognitive impairment may pose additional burden on caregivers, affecting their attitudes to the extent that patients notice a change. Absence of positive support and critical responses from caregivers may have negative effects on patients.25,31

Although the MMSE is considered an inadequate measure of cognitive impairment in ALS, we did find a significant correlation between the ALS-CBS and MMSE. However, only 2% had scores below 24 (total range is 0–30), which is the MMSE cutoff for cognitive impairment. This finding is supported by the literature and is considered to reflect the fact that the MMSE is weighted toward Alzheimer disease (AD)-based memory impairment and is not sensitive to the executive functioning changes seen in ALS dementia.

The striking contrast between the risk in patients with behavioral impairment and those with cognitive impairment suggests that clinicians may offer additional evaluation and resources to patients with behavioral changes and their families as they appear specifically at risk of comorbid depression, stress, and poorer quality of life. Since the ultimate goal of our research is to improve patient care, this important finding needs further study including the development of targeted interventions for patients, family, friends, and aides.

Expressions of a wish to die were unrelated to either cognitive or behavioral impairment. In our earlier report, we did find associations among depressive symptoms, measures of distress, and wish to die.6 However, of the 62 patients who expressed a wish to die in this study, only 23 (37%) were clinically depressed. This may account for the apparent inconsistency in the current study of finding an association between depression and behavioral impairment, but no association between behavioral impairment and wish to die.

Most patients who expressed a wish to die were not clinically depressed, which is useful to consider in the context of policy debate about physician-assisted death. Opponents suggest that patient autonomy and self-determination are obviated by the presence of depression and associated cognitive impairment. Our data showed no consistent association between depression and cognitive impairment, only a minimal association between depression and wish to die, and thus no evidence of association between cognitive impairment and wish to die for most patients. Patients with ALS should not be excluded from physician-assisted death participation (where legal) based on such assumptions.

Given the association between cognitive impairment and depression in the psychiatric literature, we would have expected to find an association here but we did not. Perhaps the brief depression and cognitive impairment screens used in this study were insufficiently sensitive. Another possibility is that these patients had milder depression or cognitive impairment than patients reported in studies showing such an association. Alternatively, this ALS sample may differ from patients studied in the depression and AD literature, which dominate the depression-cognition field. The frontotemporal cognitive changes seen in ALS are distinct in that they are characterized by more anterior, limbic regions, as opposed to the predominantly posterior neuron loss in AD. Conceivably, the unique pattern in ALS–frontotemporal dementia (FTD) neuronal loss in bilateral32 or predominantly right hemisphere33 frontotemporal emotional circuits disrupts the typical circuitry underlying depression seen in AD, for example. This may explain why we found little evidence of depression in patients with ALS who had purely cognitive deficits.

Ninety percent of our patients did not meet criteria for a full dementia diagnosis (FTD), and were only recently diagnosed with ALS. We were able to compare patients with and without depression, all of whom had behavioral impairment (groups 3 and 4). As it turned out, they did not differ on any psychiatric or psychosocial scale and were combined in all of our analyses of behavioral impairment. The foregoing discussion of neuronal loss accounting for the absence of depressive affect is thus unlikely to apply to this sample. An alternative explanation is that these patients were not clinically depressed.

Study limitations.

Although the cognitive and behavioral screening tests we used have been validated in the ALS population, future studies of the relationships among depression, wish to die, and cognitive-behavioral functioning would be strengthened with the use of a full neuropsychological examination and the Strong criteria.29 Furthermore, the ALS-CBS behavioral ratings were all made by the patient's spouse or other family caregiver, not on clinicians' observations of behavior. If the spouse is depressed or burdened by their role, they may not be impartial reporters.

This study is unusual in that we disentangled cognitive and behavioral changes in patients with ALS. Our findings suggest that behavioral changes seen in patients with ALS may reflect more widespread clinical problems, while reduced cognitive function has fewer associated manifestations.

The role of depression in AD and vascular dementia is well established, but the role of depression in FTD is not. A recent meta-analysis found considerable variation in the presence of depression in patients with FTD, echoing our findings and suggesting that a more rigorous and standardized approach is needed.34

Overall, we found a consistent pattern of psychological distress and depression associated with behavioral impairment as reported by family caregivers on the ALS-CBS. Problems for either patients or family caregivers related to behavioral problems are seldom addressed by clinicians. We did not find an association between distress and depression with cognitive impairment, measured by either the ALS-CBS or the MMSE. Our findings are based on cross-sectional data. Longitudinal data would show whether depression and behavioral impairment are causally linked, and if so, in what direction. Establishment of such a link would facilitate interventions likely to have a therapeutic influence on both domains.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are deeply grateful for the patients and their families who enthusiastically participated in this labor-intensive study. The authors express their thanks to Dr. Annette Kirshner at NIEHS for her kind advice and strong support. Georgia Christodoulou, MA, helped with manuscript preparation and reviewed the manuscript.

GLOSSARY

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CBS

Cognitive Behavioral Screen

- COSMOS

Multicenter Cohort Study of Oxidative Stress

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition)

- DSM-5

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition)

- FBI

Frontal Behavioral Inventory

- FTD

frontotemporal dementia

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- PANAS

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule

- PHQ

Patient Health Questionnaire

- VAS

visual analog scale

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Editorial, page 1312

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Rabkin designed the interview module containing the psychiatric and psychosocial measures, which she selected. She trained interviewers in their administration, and took the lead in writing up the results from the baseline study visit of this cohort. Dr. Murphy designed the neurocognitive and neurobehavioral measures used in this study, trained staff at the 16 participating sites, and took the lead in writing up the baseline findings from this cohort study. Dr. Goetz, a Research Scientist at New York State Psychiatric Institute, and faculty member in the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, performed the statistical analyses. Dr. Factor-Litvak is co–principal investigator of this NIH-funded cohort study, and as such participated in all aspects of the design and conduct of the study including statistical analyses. Dr. Mitsumoto is the principal investigator of this NIH-funded cohort study, and as such was involved in all aspects of this project including design, data collection, analyses, and manuscript preparation.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by NIEHS R01ES016348 and Wings Over Wall Street. NIH (NIEHS; R01ES016348) funded the entire study and MDA funded an earlier study, which was incorporated into the ALS COSMOS. MDA Wings, Adams Foundation, and Ride for Life supported part of the study as well.

DISCLOSURE

J. Rabkin, R. Goetz, J. Murphy, and P. Factor-Litvak report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. H. Mitsumoto received research support from SPF, MDA Wings Over Wall Street, NIEHS (R01ES016348) and private donations from Mr. and Mrs. David Marren. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitsumoto H, Factor-Litvak P, Andrews H, et al. ALS Multi-Center Study of Oxidative Stress (COSMOS): study methodology, recruitment, and baseline demographic and disease characteristics. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2014;15:192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganguli M, Yangchun D, Dodge H, Ratcliff G, Chang C. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in late life: a prospective epidemiological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63:153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potter G, Steffens D. Contribution of depression to cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults. Neurologist 2007;13:105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin MP, Mitchell P, Goodwin G. Cognitive deficits in depression: possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etkin A, Patenaude B, Song Y, Usherwood T, Rekshan W, Schatzberg A. A cognitive-emotional biomarker for predicting remission with antidepressant medications: a report from the iSPOT trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40:1332–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy J, Factor-Litvak P, Goetz R, et al. Cognitive-behavioral screening reveals prevalent impairment in a large multicenter ALS cohort. Neurology 2016;86:813–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabkin JG, Goetz R, Factor-Litvak P, et al. Depression and wish to die in a multicenter cohort of ALS patients. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2015;16:265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ringholz GM, Appel SH, Bradshaw M, Cooke NA, Mosnik DM, Schulz PE. Prevalence and patterns of cognitive impairment in sporadic ALS. Neurology 2005;65:586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phukan J, Elamin M, Bede P, et al. The syndrome of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lillo P, Hodges JR. Cognition and behaviour in motor neurone disease. Curr Opin Neurol 2010;23:638–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrahams S, Newton J, Niven E, Foley J, Bak TH. Screening for cognition and behaviour changes in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2014;15:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganzini L, Johnston W, McFarland B, Tolle S, Lee M. Attitudes of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their caregivers toward assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 1998;339:967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammer EM, Hacker S, Hautzinger M, Meyer T, Kubler A. Validity of the ALS-depression-inventory (ADI-12): a new screening instrument for depressive disorders in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Affect Disord 2008;109:213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McElhiney M, Rabkin J, Gordon P, Goetz R, Mitsumoto H. Prevalence of fatigue and depression in ALS patients and change over time. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:1146–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabkin JG, Albert S, Del Bene M, O'Sullivan I, Tider T, Rowland L. Prevalence of depressive disorders and change over time in late-stage ALS. Neurology 2005;65:62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. A revised El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2000. Available at: www.wfnals.org. Accessed March 28, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Carvallho M, Dengler R, Eisen A, et al. Electrodiagnostic criteria for diagnosis of ALS. J Clin Neurophysiol 2008;119:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA 1999;282:1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974;42:861–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson D, Clark L, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS Scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linn MW. A Global Assessment of Recent Stress Scale (GARS). Int J Psychiatry Med 1985–1986;15:47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q). In: Rush AJ, First M, Blacker D, editors. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2008:133–134. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manne S, Pape S, Taylor K, Dougherty J. Spouse support, coping and mood among individuals with cancer. Ann Behav Med 1999;21:111–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analog scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health 1990;13:227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolley-Levine S, York M, Moore DH, et al. Detecting frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS: utility of the ALS Cognitive Behavioral Screen (ALS-CBS). Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2010;11:303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kertesz A, Nadkarni N, Davidson W, Thomas AW. The Frontal Behavioral Inventory in the differential diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2000;6:460–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strong M, Grace G, Freedman M, et al. Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of frontotemporal cognitive and behavioural syndromes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009;10:131–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasson-Ohayon I, Goldzweig G, Braun M, Calinsky D. Women with advanced breast cancer and their spouses: diversity of support and psychological distress. Psychooncology 2010;19:1195–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang JL, Eng M, Lomen-Hoerth C, et al. A voxel-based morphometry study of patterns of brain atrophy in ALS and ALS/FTD. Neurology 2005;65:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy JM, Henry RG, Langmore S, Kramer J, Miller B, Lomen-Hoerth C. Continuum of frontal lobe impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2007;64:530–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakrabarty T, Sepehry A, Jacova C, Ging-Yuek RH. The prevalence of depressive symptoms in frontotemporal dementia: a meta-analysis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2015;39:257–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.