Abstract

This study reports on implementation of the CommunityRx system, a population health innovation that promoted clinic-community linkages via: a youth workforce (MAPSCorps) that conducted an annual community resource census; Community Health Information Specialists (CHIS) who supported cross-sector resource navigation; and a health information technology (HIT) for prescribing community resources. Between 2012–14, MAPSCorps identified 19,589 public-serving places in the 106mi2 implementation region. CHIS used these data to generate an inventory of nearly 15,000 health-promoting resources. The HIT platform was integrated with 3 electronic health record (EHR) systems at 33 clinical sites to map 37 prevalent health and wellness conditions to community resources; 253,479 personalized HealtheRx “prescriptions” were generated for approximately 113,000 participants. Participants found the HealtheRx very useful (83%); 19% went to a place they learned about from the HealtheRx. This study demonstrates the feasibility of using HIT and workforce innovation to bridge the gap between clinical and other health-promoting sectors.

INTRODUCTION

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) shifts the value proposition in health care delivery from fees generated by delivering medical services to people with illness to savings generated by optimizing the physical and mental health of the population served. Physicians1 and other caregivers2 recognize the importance of community-based resources for effective prevention and management of disease, but access to high quality information about these resources is exceedingly poor. Effective population health management requires an information technology (IT) infrastructure, driven by high quality community resource data, that enables health care providers and consumers to address basic, wellness, and disease management needs.

Electronic medication prescribing (“e-prescribing”) establishes the feasibility of integrating IT infrastructure across sectors to promote population health. Medication e-prescribing produces data used by the pharmaceutical industry, insurers, and policymakers for drug development, coverage, and quality monitoring. By 2014, 70% of physicians and 96% of community pharmacies were exchanging data via a single, integrated e-prescribing infrastructure.3 An analogous IT system, similarly supported by policy incentives and a dynamic source of high-quality community resource data, could enable cross-sector accountability for and optimization of population health.

In 2011, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) announced the Health Care Innovation Award (HCIA) funding opportunity. HCIA called for “the most compelling new ideas to deliver better health and improved care at lower cost,” emphasizing technology-based, scalable ideas with potential to impact underserved populations and create jobs.4 CommunityRx, a HCIA innovation, adapted the Kilbridge e-prescribing model (Appendix Exhibit 1)5,6 and an asset-based, community engaged approach7 to engineer an IT solution that enabled clinicians to e-prescribe community resources for basic, wellness, and disease self-management needs.

The CommunityRx intervention included three components: (1) a youth workforce (MAPSCorps) that conducted an annual census of community resources, (2) Community Health Information Specialists (CHIS) who both surveyed community resources and supported participant navigation to resources, and (3) an IT platform for community resource prescribing. The IT platform interfaced with EHR workflows to generate personalized “HealtheRx prescriptions” (Appendix Exhibit 2)6 delivered to the patient at the point of care.

We report on implementation of the CommunityRx system, examining process-based outcomes. The HCIA application required innovators to project the expected impact and propose a business plan for sustainability beyond the 36 month funding period. Self (NCT02411409) and external evaluations,8 assessing percent change in cost per beneficiary per year, are underway.

STUDY DATA AND METHODS

The first 8 months of the award (7/12–2/13) included Institutional Review Board approval and workforce and IT development. CommunityRx used continuous quality improvement and rapid cycle iteration methods.9

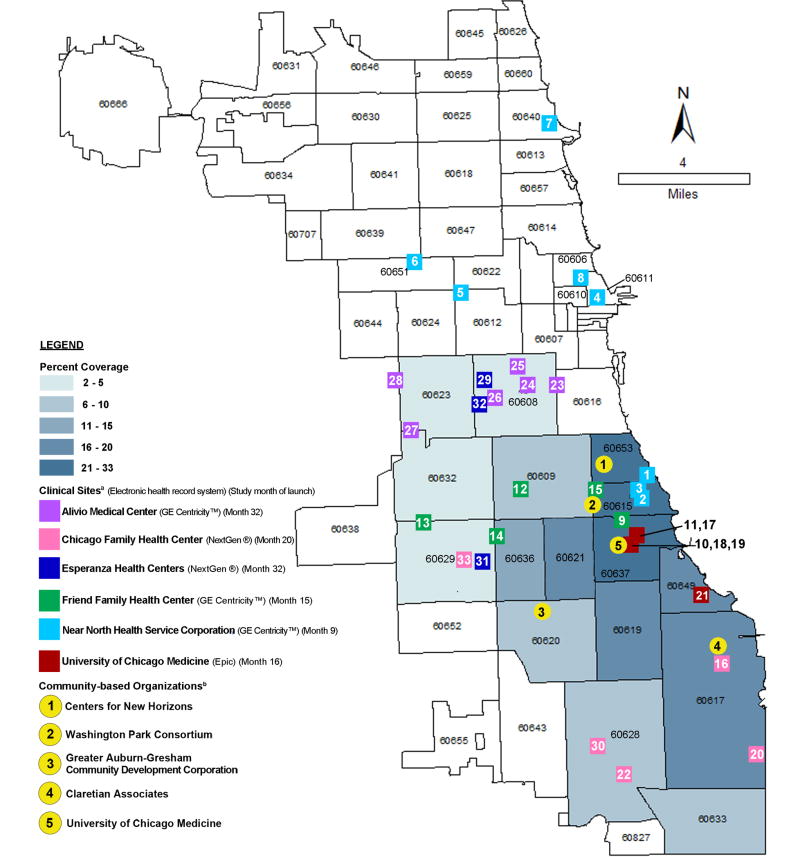

In month 9, the CommunityRx system launched at one federally qualified health center (FQHC). Academic medical (University of Chicago affiliates) and community (FQHC) sites were recruited to ensure broad geographic coverage, wide inclusion of Medicare- and Medicaid-eligible people, and diversity of practice types (e.g. school-based, senior center, emergency care) and EHR platforms (Exhibit 1). CHIS, located at the University of Chicago and at community-based organizations across the region, supported participant navigation to resources and surveyed community service providers (CSPs) in assigned service areas. By month 28, the implementation region included 16 contiguous south and west side Chicago ZIP codes (106mi2, 993K total population, 58% <200% federal poverty level), including the University of Chicago’s primary service area. Individuals residing in the implementation region seen at participating clinical sites were eligible. “Participants” included individuals for whom at least one HealtheRx was generated.

Exhibit 1. CommunityRx implementation region by ZIP code, showing penetration of the HealtheRx distribution, and locations of 33 clinical sites, electronic health record vendor types, and Community Health Information Specialists (CHIS).

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of CommunityRx database and population data obtained from American Community Survey, 2014, 5 Year, S0101.

NOTES Penetration of the HealtheRx was measured by the estimated percent of population residing in each ZIP code that received at least one HealtheRx months 9–35 of the 36 month CommunityRx implementation period. Several Near North Health Service Corporation sites located outside the implementation region adopted the CommunityRx system after a physician trained at site #1 to use CommunityRx “hacked” the system to function at another site where he worked. This unexpected spread prompted us to expand CommunityRx prescribing functionality to all affiliated clinical sites providing care for patients who were residents in the implementation geography. aClinical sites included 27 Federally Qualified Health Centers (5 of these were school-based clinics) operated by 5 corporations, and 6 academic medical center-affiliated sites (4 outpatient practices and an adult and pediatric emergency department). Sites are numbered in order of deployment. bEnglish and Spanish-speaking CHIS were deployed at partnering community-based organizations (organizations 1–4) and with the central team (organization 5).

Community Resource Inventory

MAPSCorps paired local high school students with science-oriented young adults (mostly college students) to conduct an annual “feet-on-the-street” census (summers 2013–15) of all CSPs open to the public (“operating”). We have previously described the MAPSCorps protocol in detail and reported that methods yield far more accurate community resource data than widely used secondary sources.10 MAPSCorps methods have been replicated in New York City and Niagara Falls, NY (supported by New York State Health Foundation), and Edgecombe and Nash Counties, NC (supported by NIH/NHLB 2K24 HL 105493-06). In short, using the MapApp™ smartphone application, youth walked block by block, gathering data by direct observation for each CSP including: name, address, phone number, the CSP’s primary function, and whether it was operating. MAPSCorps data were posted annually to www.mapscorps.org and www.dondeesta.org. Youth demographics and employment history were self-reported.

In month 7, we initiated telephone surveys with CSPs identified by MAPSCorps. These surveys, conducted primarily by CHIS, collected data about the resources (programs and services) provided by each place, including eligibility and cost. Surveys prioritized places that were likely to offer resources indicated for wellness and the target health conditions. Resource data were posted to www.HealtheRx.org.

Community Resources E-prescribing

The IT solution linked EHR platforms to the CommunityRx system. At the end of the clinical visit, data from participants’ EHR (ICD-9 codes, age, home address, primary language and other variables) were sent via automated, secure web call to query the CommunityRx server. Using an algorithm that combined clinical and public health guidelines with expert opinion, the server generated the HealtheRx: a personalized list of community resources near the participant’s home address (Appendix Exhibit 3).6 The HealtheRx returned within seconds (median 2.1) to a local printer and posted to the EHR. The participant received the HealtheRx from a health care provider with a brief (1–2 sentence) explanation that included orientation to the CHIS role and CHIS contact information. In 29 sites, the HealtheRx printed with the “click” that triggered the visit summary (a meaningful use requirement);11 in 4 sites, one “extra click” was required.

Process measures are reported for months 9–36, with the exception of measures requiring EHR data which were only available for analysis through month 35. Analyses of resource referral patterns used data from months 30–35 when the CommunityRx system, including target conditions and geography, were at steady state.

Participant experience was assessed months 9–36 by a cross-sectional phone survey. Participants (~20/month) were recruited through an advertisement on the HealtheRx that offered a monetary incentive. Provider experience was assessed months 9–36 using an anonymous cross-sectional self-administered survey. Baseline surveys were collected pre-launch and follow-up surveys were conducted every 6 months post-launch. Using an item from a 2011 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) survey,1 we assessed providers’ attitudes about patients’ social needs. This study analyzes provider data from 11 sites with consistent participation at baseline and 12 months.

Analyses were conducted using Stata/SE vs14.0 (College Station, Texas).

Limitations

EHR data were available for 19 sites; data for 14 FQHCs (most of which launched in the last 5 months of the implementation) were excluded due to acquisition and cost barriers. Excluded sites’ payer mix and patient volume, age, and income were similar to included sites, but they had a higher proportion of Hispanic patients.12 Although EHR data included a unique patient identifier, confidentiality concerns and cost prohibited linkage of individual-level EHR data across sites. Self-reported youth, participant, and provider survey data may be limited by response bias. Provider survey data are limited by variable participation across sites.

RESULTS

Community Resource Inventory

MAPSCorps covered 106mi2; youth walked an average 4.6 miles/day. MAPSCorps identified 19,589 places providing community resources. During the implementation, MAPSCorps created 224 paid positions for youth (83% identified as black, non-Hispanic; 9% Hispanic, non-black; 2% black, Hispanic; 51% female) and 64 paid positions for young adult mentors. MAPSCorps was the first paid employment for 53% of youth.

English and Spanish-speaking CHIS were deployed at partnering community-based organizations (n=4) and with the central team (n=3) (Exhibit 1). CHIS used MAPSCorps data to produce the CSP inventory (Appendix Exhibit 4)6. Of 19,589 CSPs, 30% (n=5,952) completed a baseline survey.

Community Resources E-prescribing

The CommunityRx IT system was integrated with three EHR platforms (Epic, GE Centricity™, NextGen®) operating at 33 clinical sites (Exhibit 1). By month 28, the system was generating HealtheRxs for 37 target conditions (wellness for 7 age groups; 23 medical, 6 mental or behavioral health conditions; and homelessness)(Appendix Exhibit 3).6

More than 1,600 providers (physicians, nurses and other staff), were trained to deliver the HealtheRx. At baseline, 86% (n=552/644) wished the health care system would pay for connecting patients to resources for unmet social needs and 19% (n=119/642) were “not at all confident” in their ability to meet their patients’ unmet social needs. The proportion “not at all confident” was 15% at 12 months (n=27/185)(Appendix Exhibit 5).6

During months 9–35, the CommunityRx system generated for an estimated 113,295 unique individuals, one or more HealtheRxs (253,479 total), with more than 8 million community resource referrals. More than a quarter of the population living in each of three of the 16 implementation ZIP codes received at least one HealtheRx (Exhibit 1).

Of participants surveyed (N=458), the majority (71%) found places listed that they did not know were in their community; 19% reported they went to a place they learned about because it was on their HealtheRx. Overall satisfaction was high: 79% were very satisfied and 83% found the HealtheRx to be very useful. In month 19, we added a survey item to assess spread of HealtheRx information from participants to others: half (183/374, 49%) reported telling others about the HealtheRx. All but one person (reporting a neutral comment) told others something positive about the HealtheRx.

Looking at 19/33 sites for which complete steady state data (months 30–35) were available, an estimated 49,655 unique participants received a HealtheRx (Exhibit 2), of which 11,848 were referred on average per month to one or more of 4,646 resources at 1,935 CSPs (Appendix Exhibit 6). The top referred resources are shown in Exhibit 3. We estimated potential strain on highly referred resources by the average number of participants referred/month/resource. The most strained resources included: smoking cessation (n=1001 participants referred/month/resource); pest control (n=497) and mold assessment (n=434); warming/cooling centers (n=295); weight loss (n=205); and help paying mortgage/rent (n=209). By ZIP code, total resources per 10,000 population ranged from 148 to 236 (Exhibit 4, Appendix Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 2.

CommunityRx participant characteristics by clinical site using data for months 30–35 of the 36 month CommunityRx implementation period, based on analysis of 49,655 participants for whom electronic health record data were available (19/33 clinical sites).

| Federally Qualified Health Center Patients (N=17,351) |

Emergency Department Patients (N=18,253) |

Hospital Out-Patient Clinic Patients (N=14,051) |

Estimated Total Unique Patients (N=49,655) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age at first HealtheRx | ||||||||

| <12 years old | 6,575 | 37.9 | 6,414 | 35.1 | 1,741 | 12.4 | 14,730 | 29.7 |

| 12–17 years old | 1,553 | 9.0 | 1,480 | 8.1 | 480 | 3.4 | 3,513 | 7.1 |

| 18–64 years old | 8,616 | 49.7 | 8,706 | 47.7 | 6,998 | 49.8 | 24,320 | 49.0 |

| 65–74 years old | 439 | 2.5 | 818 | 4.5 | 2,019 | 14.4 | 3,276 | 6.6 |

| 75 years or older | 168 | 1.0 | 835 | 4.6 | 2,813 | 20.0 | 3,816 | 7.7 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 10,864 | 62.6 | 10,718 | 58.7 | 10,116 | 72.0 | 31,698 | 63.8 |

| Male | 6,485 | 37.4 | 7,533 | 41.3 | 3,935 | 28.0 | 17,953 | 36.2 |

| Patient declined or missing | 2 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.0 |

| Race | ||||||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 18 | 0.1 | 17 | 0.1 | 22 | 0.2 | 57 | 0.1 |

| Asian/Mideast Indian | 74 | 0.4 | 157 | 0.9 | 630 | 4.5 | 861 | 1.7 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 34 | 0.2 | 16 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.0 | 55 | 0.1 |

| Black | 15,111 | 87.1 | 16,378 | 89.7 | 10,071 | 71.7 | 41,560 | 83.7 |

| White | 1,968 | 11.3 | 981 | 5.4 | 2,770 | 19.7 | 5,719 | 11.5 |

| More than 1 race | 44 | 0.3 | 342 | 1.9 | 261 | 1.9 | 647 | 1.3 |

| Patient declined or missing | 102 | 0.6 | 362 | 2.0 | 292 | 2.1 | 756 | 1.5 |

| Ethnicity | 0 | |||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,775 | 10.2 | 782 | 4.3 | 593 | 4.2 | 3,150 | 6.3 |

| Non-Hispanic | 15,486 | 89.3 | 17,081 | 93.6 | 13,194 | 93.9 | 45,761 | 92.2 |

| Patient declined or missing | 90 | 0.5 | 390 | 2.1 | 264 | 1.9 | 744 | 1.5 |

| Insurance statusa | ||||||||

| Public | 13,876 | 80.0 | 12,139 | 66.5 | 6,780 | 48.3 | 32,795 | 66.0 |

| Self-pay | 1,673 | 9.6 | 1,726 | 9.5 | 54 | 0.4 | 3,453 | 7.0 |

| Private | 1,237 | 7.1 | 4,188 | 22.9 | 6,444 | 45.9 | 11,869 | 23.9 |

| Patient declined, missing or unknown | 565 | 3.3 | 200 | 1.1 | 773 | 5.5 | 1,538 | 3.1 |

| Total number of HealtheRx | ||||||||

| Mean (Range, Standard Deviation) | 1.68 (1–11,1.1) | 1.2 (1–17, 0.7) | 1.9 (1–22, 1.5) | 1.6 (1–22, 1.1) | ||||

| 1 | 10,474 | 60.4 | 15,172 | 83.1 | 7,374 | 52.5 | 33,020 | 66.5 |

| 2 | 4,022 | 23.2 | 2,311 | 12.7 | 3,566 | 25.4 | 9,899 | 19.9 |

| 3 | 1,658 | 9.6 | 502 | 2.3 | 1,602 | 11.4 | 3,762 | 7.6 |

| 4 or more | 1,197 | 6.9 | 268 | 1.5 | 1,509 | 10.7 | 2,974 | 6.0 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from: 1) CommunityRx database for months 30–35, 2) University of Chicago electronic health records for emergency departments Bernard Mitchell Hospital Emergency Room and Comer Children’s Emergency Room, 3) University of Chicago electronic health records for hospital outpatient clinics including Primary Care Group, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Children’s Medical Group, and Senior Outpatient Health Centers, and 4) Electronic health records from Federally Qualified Health Centers, Near North Health Service Corporation (8 clinical sites) and Friend Family Health Center (5 clinical sites).

NOTES Estimated participant totals do not represent unique patients because, in order to maximize confidentiality, personally identifying information needed to link individuals’ electronic health record data across the 3 types of clinical sites were not available to the research team. A small overlap in patients across sites is possible.

Insurance status for patients receiving a HealtheRx in the emergency department was estimated based on available data (n=12,587).

Exhibit 3.

Average monthly resource referrals to the most commonly referred resource types and subtypes for months 30–35 of the 36 month CommunityRx implementation period, based on analysis of 79,174 HealtheRxs for an estimated 49,655 total participants for whom electronic health record data were available (19/33 clinical sites).

| Total resources in implementation region | Average # of Participants Receiving Referral/Month | Average # of Referrals/Month | Average # of Participants Receiving Referral/Month/Resource | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Type | n | % | n | % | n | % | n |

| Food pantry | 139 | 3.0 | 10,089 | 85.1 | 22,420 | 5.8 | 73 |

| Healthy eating classes | 72 | 1.5 | 9,744 | 82.2 | 21,622 | 5.6 | 135 |

| Fresh fruits and vegetables | 248 | 5.3 | 9,570 | 80.8 | 21,163 | 5.4 | 39 |

| Individual counseling | 125 | 2.7 | 9,373 | 79.1 | 20,882 | 5.4 | 75 |

| Group exercise classes | 140 | 3.0 | 7,342 | 62.0 | 16,387 | 4.2 | 521 |

| Weight loss classes | 32 | 0.7 | 6,566 | 55.4 | 14,665 | 3.8 | 205 |

| Classes to help you quit smoking | 7 | 0.2 | 7,006 | 59.1 | 12,041 | 3.1 | 1001 |

| Help paying gas, water and electricity | 39 | 0.8 | 5,377 | 45.4 | 11,797 | 3.0 | 138 |

| Help paying mortgage and rent | 24 | 0.5 | 5,014 | 42.3 | 11,042 | 2.8 | 209 |

| Dental care | 163 | 3.5 | 4,814 | 40.6 | 10,466 | 2.7 | 30 |

| Fill prescriptions | 147 | 3.2 | 4,117 | 34.7 | 9,279 | 2.4 | 28 |

| Walking groups | 24 | 0.5 | 3,911 | 33.0 | 8,828 | 2.3 | 163 |

| Pest control | 8 | 0.2 | 3,979 | 33.6 | 8,770 | 2.3 | 497 |

| Stress management classes | 20 | 0.4 | 3,810 | 32.2 | 8,552 | 2.2 | 191 |

| Blood pressure monitors | 55 | 1.2 | 3,767 | 31.8 | 8,523 | 2.2 | 68 |

| Help finding jobs | 90 | 1.9 | 3,713 | 31.3 | 8,071 | 2.1 | 41 |

| Job training | 83 | 1.8 | 3,637 | 30.7 | 7,917 | 2.0 | 44 |

| Warming and cooling centers | 11 | 0.2 | 3,246 | 27.4 | 7,152 | 1.8 | 295 |

| Parenting support groups | 34 | 0.7 | 3,064 | 25.9 | 6,676 | 1.7 | 90 |

| Mold assessment and/or removal | 5 | 0.1 | 2,170 | 18.3 | 4,803 | 1.2 | 434 |

| Tutoring | 136 | 2.9 | 1,756 | 14.8 | 3,735 | 1.0 | 13 |

| Daycare | 293 | 6.3 | 1,610 | 13.6 | 3,582 | 0.9 | 5 |

| Birth control | 71 | 1.5 | 1,364 | 11.5 | 3,272 | 0.8 | 19 |

| Condoms | 38 | 0.8 | 1,193 | 10.1 | 2,769 | 0.7 | 31 |

| Sex education | 25 | 0.5 | 1,193 | 10.1 | 2,769 | 0.7 | 48 |

| After school programs | 170 | 3.7 | 1,115 | 9.4 | 2,374 | 0.6 | 7 |

| Average Total/Month | 4,646 | 100.0 | 11,848 | 100.0 | 388,335 | 100.0 | 3 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from: 1) CommunityRx database for months 30–35, 2) University of Chicago electronic health records for emergency departments Bernard Mitchell Hospital Emergency Room and Comer Children’s Emergency Room, 3) University of Chicago electronic health records for hospital outpatient clinics including Primary Care Group, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Children’s Medical Group, and Senior Outpatient Health Centers, and 4) Electronic health records from Federally Qualified Health Centers, Near North Health Service Corporation (8 clinical sites) and Friend Family Health Center (5 clinical sites).

NOTES Excludes 3 HealtheRxs generated (for the condition “speech delay”) for Spanish-speakers for whom no resources were available. Estimated 49,655 total participants does not represent unique patients because personally identifying information needed to link individuals’ electronic health record data across the 3 types of clinical sites were not available to the research team. A small overlap in patients across sites is possible.

Exhibit 4.

Implementation region population characteristics, and resource availability per 10,000 population, stratified by subset of ZIP codes with complete resource information.

| ZIP Code | CommunityRx Participants Estimated total participants receiving HealtheRx months 9 to 35 | Implementation Region Population Characteristics | CommunityRx Resources | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 65+ years | African American | Hispanic | Below FPLa | Uninsuredb | Unemploymentc | Total resources available for referrald | All resources per 10,000 population | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| n | n | % | % | % | % | % | % | n | n | |

| 60649 | 8,852 | 45,201 | 13.4 | 93.6 | 2.5 | 32.5 | 20.1 | 20.9 | 668 | 147.8 |

| 60617 | 15,124 | 82,685 | 14.3 | 54.5 | 37.9 | 25.7 | 18.8 | 20.4 | 1,236 | 149.5 |

| 60636 | 4,725 | 40,164 | 12.8 | 93.2 | 4.1 | 38.8 | 24.6 | 35.1 | 628 | 156.4 |

| 60619 | 12,260 | 64,245 | 15.3 | 97.2 | 1.3 | 28.6 | 18.1 | 23.4 | 1,014 | 157.8 |

| 60620 | 7,021 | 71,907 | 16.0 | 96.9 | 1.4 | 28.8 | 19.1 | 26.1 | 1,191 | 165.6 |

| 60609 | 5,269 | 62,405 | 8.0 | 26.4 | 51.0 | 32.7 | 25.0 | 22.5 | 1,076 | 172.4 |

| 60637 | 16,073 | 48,851 | 10.6 | 77.4 | 1.9 | 37.7 | 14.3 | 21.5 | 930 | 190.4 |

| 60615 | 11,567 | 41,141 | 12.4 | 59.7 | 5.7 | 25.3 | 13.2 | 13.9 | 901 | 219.0 |

| 60621 | 5,057 | 32,619 | 11.1 | 95.5 | 1.9 | 48.5 | 22.0 | 36.0 | 728 | 223.2 |

| 60653 | 7,784 | 31,038 | 13.5 | 91.6 | 1.6 | 38.3 | 14.4 | 23.1 | 733 | 236.2 |

| Total | 93,732 | 520,256 | 13.0 | 76.0 | 13.9 | 32.3 | 19.1 | 23.6 | 9,105 | 175.0 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from: 1) CommunityRx database for months 9–35, and 2) American Community Survey, 2014, 5-Year estimates.

NOTES Data presented are limited to 10 ZIP codes with resource inventory survey data available from the start of our survey activities. Therefore, the estimated total participants receiving a HealtheRx months 9 to 35 and the population characteristics reflect those for the 10 ZIP code subset. For the 16 ZIP code region, total population 975,400, an estimated 113,295 participants received a HealtheRx months 9 to 35.

Counts and percentages of individuals living below FPL (federal poverty level) are based on the number of individuals for whom poverty level could be determined: this includes university students living off campus (N=511,967).

Counts and percentages of uninsured individuals includes only civilian, non-institutionalized individuals (N=517,559).

Counts and percentages for unemployment includes only those 16 years and older (N=403,857).

Snapshot of currently available resources (May 2016) at CSPs that completed a resource survey.

During months 9–36, CHIS received 888 requests (<1% of all participants) for assistance accessing community resources (631 by phone, 193 by text, 64 by email or in person) (Appendix Exhibit 8).6 Between months 31–36 at sites affiliated with one FQHC partner, participants could elect to receive text messages from CHIS. Among those who received a text message from a CHIS in tandem with receipt of the HealtheRx (n=1448), the engagement rate increased to 14%. Two crisis requests (suicidality, child safety) requiring physician involvement were promptly resolved. Of the services participants requested, 71% were available at the participant’s medical home.

In the final quarter of the implementation period, clinical partners were given the option to have the CommunityRx system removed from their EHRs. Every partnering organization, with the exception of one planning to switch to a new EHR vendor, opted to continue use. Paraphrased from one internist at an FQHC: “CommunityRx is now woven into the fabric of what we do.”

DISCUSSION

In 2011, CMMI issued its first HCIA opportunity, described by the White House as “a call to action for technology and data innovators to team with care innovators to propose solutions that can be implemented with speed and have the opportunity to scale.”4 The CommunityRx system, built in partnership with the Office of the National Coordinator’s Chicago Health Information Technology Regional Extension Center and others, was operational in 9 months and scaled to integrate with 3 EHR platforms at 33 diverse clinical sites. More than 113,000 patients, 1,600 clinicians, nearly 6,000 CSPs, and hundreds of young people were engaged. Participant satisfaction was consistently high. All but one clinical partner elected to continue operating CommunityRx after the HCIA funding ended. Most CMMI interventions targeted a specific disease or high risk subpopulation. In contrast, the CommunityRx system was designed horizontally - an infrastructure solution to serve people of all ages, seen in diverse clinical settings, for primary prevention and for management of a wide range of social and medical conditions.

The adapted Kilbridge model for prescribing community resources (Appendix Exhibit 1)5,6 provides a useful framework for analysis of this study’s findings. The fulfillment phase, the period after the participant received the HealtheRx, began with evaluation: the clinician oriented the participant to the HealtheRx, including cost and eligibility information, and highlighted the CHIS information. Published evidence about patient adherence to community resource referrals was very limited when we proposed the CommunityRx innovation. In a small study of United Way 2-1-1 callers, 5/39 people (12.8%) referred to CSPs reported making an appointment.13 Based in part on this finding, we estimated that 12% of participants would contact a CHIS or a CSP after receiving a HealtheRx.

The observed rate of engagement with the CHIS in our study was very low (<1%). CHIS hypothesized that the low rate of engagement was due to the comprehensiveness of information provided on the HealtheRx; they thought the HealtheRx provided most participants the information they needed to directly contact CSPs. This explanation is corroborated by the higher than expected rate (19%, by self-report) of participant presentation to at least one CSP that they learned about because it was on the HealtheRx.

The 19% community resource “dispense” rate (the proportion of participants who visited a referred CSP) likely underestimates the impact of the CommunityRx intervention on community resource use. Most participant surveys were completed within 2 weeks of receiving a HealtheRx, so subsequent CSP visits were not captured. This estimate does not include going to CSPs on the HealtheRx (or otherwise) that participants already knew (55% said they had ever been to at least one of the CSPs on their HealtheRx). Lastly, a third of participants received 2 or more HealtheRxs; a dose-response effect is possible. SMS texting appeared to multiply the effect of the intervention: we found a 70-fold increase in the rate of CHIS-participant interaction (from 0.2% in the 6 months before to 14% during the texting implementation).

The fulfillment phase of the process is complete when a community-based resource is administered (e.g. a person participates in an Alcoholics Anonymous™ meeting or receives food donation from a pantry). Although the CommunityRx model builds on medication e-prescribing, it is important to note that the CommunityRx implementation did not digitally “close the loop” on its e-prescribing functionality. Medication e-prescribing sends an outbound message to the patient’s preferred pharmacy and indicates back to the prescriber, in the EHR workflow, information about patient fulfillment. Fulfillment occurs when the patient obtains the prescription; whether the patient administers the medication is typically ascertained during the patient-provider encounter. During the CommunityRx implementation study, we were not resourced to build an electronic interface for CSPs to receive referrals. We, therefore, could not track fulfillment beyond participant self-report. Additional technology and research are needed to more precisely estimate the effect of the HealtheRx on participant fulfillment (especially dispensing and administration) of community resources. Few empirical studies, including one RCT, of clinic-community resource referral interventions have been published;14–16 we find none that describe integration with the EHR or a closed loop IT solution.

Our findings suggest that national, cross-sector adoption of an IT solution to manage clinic-community referrals might increase CSP visibility and generate meta-data to fill a major void in knowledge about community resources. In our study, among participating CSPs, 42% had no website and many requests to CHIS were for resources the participant did not know were available at their own medical home. Meta-data from the CommunityRx implementation reveal variation in geospatial demand and wide disparities in supply of community resources. Among 10 ZIP codes with complete resource data, 26% of participants and 25% of the total population, including 27% of people 65 years and older, and 40% of Hispanic people were concentrated in 2 ZIP codes with the lowest resource density (148–150 resources/10K population versus 223–236/10K in the two highest ZIP codes). Meta-data like these were shared with CSPs during our study and are needed by communities and policymakers to monitor demand for and equitable access to community resources. By identifying resource gaps and inequities, these data can inform health-promoting policy, community planning, community benefit investment by tax-exempt hospitals, and even entrepreneurial activities.

The CommunityRx system, especially the HealtheRx, acted like a vector, spreading information about community resources well beyond participant-provider encounters. In several ZIP codes, the intervention reached more than 20% of the total population, rendering the system a penetrant population health communication tool. With support from the National Institutes on Aging, we are now studying sustainability by applying a systems science approach to quantify the community-level impact and cost-effectiveness of the CommunityRx innovation and to project impact for other communities (1R01 AG 047869-01, NCT02435511).

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates the feasibility of using IT and workforce innovation to bridge the gap, at scale, between clinical and other health-promoting sectors in one high poverty urban region. Building clinic-community linkages to address patients’ health-related social needs also generated meaningful work for youth, shined light on and produced business intelligence for local health-promoting CSPs, and produced evidence about resource gaps that can be used to inform health-promoting community investments. The CommunityRx innovation came to life because CMS, the nation’s largest health insurer, chose to test innovation and workforce development as a pathway to long-term improvement in population health. Building in part on the CommunityRx project, the CMMI Accountable Health Communities opportunity will invest $157 million over 5 years to accelerate development of cross-sector delivery models for addressing beneficiary health-related social needs.17 The Health Care Innovation Award anticipated “locally driven innovations.”18 In our community, we believe successful strategies for an enduring culture of health will be those that center on whole people (rather than diseases), engage youth, and generate value across sectors by creating meaningful, health-promoting data and jobs.7

Supplementary Material

Biographies

Stacy T. Lindau is an associate professor in the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medicine-Geriatrics and director of research and innovation at the Urban Health Initiative of University of Chicago Medicine, all at the University of Chicago, in Chicago, IL.

Jennifer Makelarski is director of epidemiology and research training in the Lindau Laboratory in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Emily Abramsohn is a researcher and director of quality assurance and data governance in the Lindau Laboratory in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Chicago.

David G. Beiser is an associate professor of medicine and pediatrics in the Section of Emergency Medicine at the University of Chicago.

Veronica Escamilla is a senior researcher in the Lindau Laboratory in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Jessica Jerome is an assistant professor in the Department of Health Sciences at DePaul University, in Chicago, and a medical anthropologist in the Lindau Laboratory in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Daniel Johnson is chief of the Section of Academic Pediatrics, and a professor in the Department of Pediatrics, director of community science for the Urban Health Initiative of University of Chicago Medicine, at the University of Chicago.

Abel N. Kho is an associate professor of medicine at Northwestern University and director of the Center for Health Information Partnerships, both in Chicago.

Karen K. Lee is director of fundraising and special programs in the Section of Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Section of Academic Pediatrics at the University of Chicago.

Timothy Long is director of performance improvement, health information technology, and research at the Near North Health Service Corporation and chief clinical officer at Alliance of Chicago Community Health Services, both in Chicago.

Doriane C. Miller is an associate professor in the Department of Medicine and director of the Center for Community Health and Vitality at the Urban Health Initiative of University of Chicago Medicine, at the University of Chicago.

Endnotes

- 1.Health Care’s Blind Side: The Overlooked Connection between Social Needs and Good Health [Internet] Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2011. Available from: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/surveys_and_polls/2011/rwjf71795. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black BS, Johnston D, Rabins PV, Morrison A, Lyketsos C, Samus QM. Unmet Needs of Community-Residing Persons with Dementia and Their Informal Caregivers: Findings from the Maximizing Independence at Home Study. J Amer Geriat Soc. 2013 Dec 1;61(12):2087–95. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabriel MH, Swain M. E-Prescribing Trends in the United States. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; Jul, 2014. (ONC Data Brief, no 18). [Internet]. [cited 2016 May 25]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/oncdatabriefe-prescribingincreases2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calling All Innovators – Health Care Innovation Challenge Open for Great Ideas [Internet] 2011 whitehouse.gov. [cited 2016 May 24]. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2011/12/07/calling-all-innovators-health-care-innovation-challenge-open-great-ideas.

- 5.Kilbridge P, Gladysheva K. California HealthCare Foundation [Internet] First Consulting Group; 2001. E-prescribing. [cited 2016 May 26]. Available from: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/PDF%20E/PDF%20EPrescribing.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 7.Lindau ST, Makelarski JA, Chin MH, Desautels S, Johnson D, Johnson WE, et al. Building community-engaged health research and discovery infrastructure on the South Side of Chicago: science in service to community priorities. Prev Med. 2011 Apr;52(3–4):200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evaluation of the Health Care Innovation Awards: Community Resource Planning, Prevention, and Monitoring [Internet] 2016 Mar; [cited 2016 May 25]. Available from: https://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/hcia-communityrppm-secondevalrpt.pdf.

- 9.Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makelarski JA, Lindau ST, Fabbre VD, Grogan CM, Sadhu EM, Silverstein JC, et al. Are Your Asset Data as Good as You Think? Conducting a Comprehensive Census of Built Assets to Improve Urban Population Health. J Urban Health. 2012 Sep 15;90(4):586–601. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9764-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “Meaningful Use” Regulation for Electronic Health Records. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 5;363(6):501–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Resources and Service Administration Data Warehouse. [cited 2016 July 22] Available from: https://findahealthcenter.hrsa.gov/

- 13.Eddens KS, Kreuter MW. Proactive screening for health needs in United Way’s 2-1-1 information and referral service. J Soc Serv Res. 2011;37(2):113–123. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2011.547445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg A, Marino M, Vikani AR, Solomon BS. Addressing families’ unmet social needs within pediatric primary care: the health leads model. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012 Dec;51(12):1191–3. doi: 10.1177/0009922812437930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page-Reeves J, Kaufman W, Bleecker M, Norris J, McCalmont K, Ianakieva V, et al. Addressing Social Determinants of Health in a Clinic Setting: The WellRx Pilot in Albuquerque, New Mexico. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016 Jun;29(3):414–8. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015 Feb;135(2):e296–304. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable Health Communities–Addressing Social Needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374(1):8–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1512532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Health Care Innovation Challenge [Internet] Washington (DC): CMMI; 2011. Nov 14, [cited 2016 Aug 11]. Available from: https://innovation.cms.gov/files/x/health-care-innovation-challenge-funding-opportunity-announcement.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.