Abstract

Background

Hikikomori, a form of social withdrawal first reported in Japan, may exist globally but cross-national studies of cases of hikikomori are lacking.

Aims

To identify individuals with hikikomori in multiple countries and describe features of the condition.

Method

Participants were recruited from sites in India, Japan, Korea and the United States. Hikikomori was defined as a 6-month or longer period of spending almost all time at home and avoiding social situations and social relationships, associated with significant distress/impairment. Additional measures included the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale, Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6), Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) and modified Cornell Treatment Preferences Index.

Results

A total of 36 participants with hikikomori were identified, with cases detected in all four countries. These individuals had high levels of loneliness (UCLA Loneliness Scale M = 55.4, SD = 10.5), limited social networks (LSNS-6 M = 9.7, SD = 5.5) and moderate functional impairment (SDS M = 16.5, SD = 7.9). Of them 28 (78%) desired treatment for their social withdrawal, with a significantly higher preference for psychotherapy over pharmacotherapy, in-person over telepsychiatry treatment and mental health specialists over primary care providers. Across countries, participants with hikikomori had similar generally treatment preferences and psychosocial features.

Conclusion

Hikikomori exists cross-nationally and can be assessed with a standardized assessment tool. Individuals with hikikomori have substantial psychosocial impairment and disability, and some may desire treatment.

Keywords: Social isolation, cross-national, culture

Introduction

The notion of hermits and recluses has existed in many cultures for time immemorial. However, in recent years a particularly severe syndrome of social withdrawal first identified in Japan has garnered the interest of researchers and the lay public alike. Called hikikomori, it has been defined as ‘a phenomenon in which persons become recluses in their own homes, avoiding various social situations (e.g., attending school, working, having social interactions outside of the home, etc.) for at least six months’ (Saito, 2010). Individuals with hikikomori are frequently reported to have social contact predominantly via the internet and some reports suggest overlap with heavy internet use (De Michele, Caredda, Delle Chiaie, Salviati, & Biondi, 2013; Lee, Lee, Choi, & Choi, 2013). An estimated 232,000 Japanese currently suffer from hikikomori, and 1.2% of community-residing Japanese between ages 20–49 have a lifetime history of hikikomori (Koyama et al., 2010). A combination of a shy personality, ambivalent attachment style and life experiences including rejection by peers and parents – among other factors – may promote the development of hikikomori (Krieg & Dickie, 2013). Furthermore, scientific studies point to genetic and other biological influences on sociality that, although not specific to hikikomori, could have implications for the study of the etiology of hikikomori (Meyer-Lindenberg & Tost, 2012). While researchers debate the merits of hikikomori as a psychiatric diagnosis (Teo & Gaw, 2010), practicing clinicians in Japan indicate they view hikikomori as a ‘disorder’ (Tateno, Park, Kato, Umene-Nakano, & Saito, 2012).

Previous reports suggest hikikomori may exist outside of Japan. For instance, case reports have described the presence of hikikomori in several other countries (Furuhashi et al., 2012; Garcia-Campayo, Alda, Sobradiel, & Sanz Abos, 2007; Sakamoto, Martin, Kumano, Kuboki, & Al-Adawi, 2005; Teo, 2013). When presented with vignettes of hikikomori, psychiatrists from nine countries around the world indicated that such cases existed in their clinical practices (Kato et al., 2012). Nonetheless, cross-national studies designed to identify hikikomori have been lacking. Reasons for the lack of recognition have included ambiguity about the features of hikikomori (Tateno et al., 2012; Watts, 2002), and inconsistent or insufficiently detailed definitions of hikikomori (Furuhashi et al., 2011; Garcia-Campayo et al., 2007; Sakamoto et al., 2005). This has caused concern that researchers may not be referring to the same phenomenon. We have previously proposed a research-grade definition of hikikomori, but this definition has not been empirically tested (Teo & Gaw, 2010). Additionally, prior reports of hikikomori have focused on assessment of psychopathology (Lee et al., 2013; Nagata et al., 2013) but fewer studies – especially outside of Japan – have examined psychosocial features more broadly, despite the common belief that sociocultural factors are important contributors to hikikomori (Kato et al., 2012). Finally, prior research has examined treatment recommendations for hikikomori by psychiatrists, but we are unaware of studies that have explored patients’ treatment preferences (Kato et al., 2012).

Aims

To identify cases of hikikomori cross-nationally;

To describe the psychosocial features and treatment preferences of individuals with hikikomori;

To explore possible differences in psychosocial features and treatment preferences of individuals with hikikomori across countries.

In this study, we examined individuals with social withdrawal using such a standardized definition of hikikomori cross-nationally.

Method

Design

We conducted a cross-national case series in India, Japan, South Korea and the United States.

Study participants

Participants who had a history of or current social withdrawal were recruited. Indian participants were referred from psychiatric outpatient clinics. Japanese and Korean participants were referrals from either a hospital or community mental health center. At the US site, participants responded to an online advertisement. All participants were adults between the ages of 18 and 39, noninstitutionalized and fluent in the local language of their respective site (English used in India). Participants with a self-reported history of schizophrenia, dementia, mental retardation or autism spectrum disorders and participants with social withdrawal due to a chronic physical illness or injury were excluded. A total of 108 individuals were screened for eligibility, with 26 excluded for not meeting criteria for hikikomori, 18 for age, 2 for schizophrenia, 1 with an autism spectrum disorder and 6 who withdrew consent. This left 55 (51%) who met initial eligibility criteria. An additional 18 individuals did not complete consent or study measures and 1 was excluded for later reporting a history of schizoaffective disorder, leaving a final sample of 36 for analysis. Participants were compensated US$50 or equivalent in local currency. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating site. All participants provided written informed consent for participation.

Measures

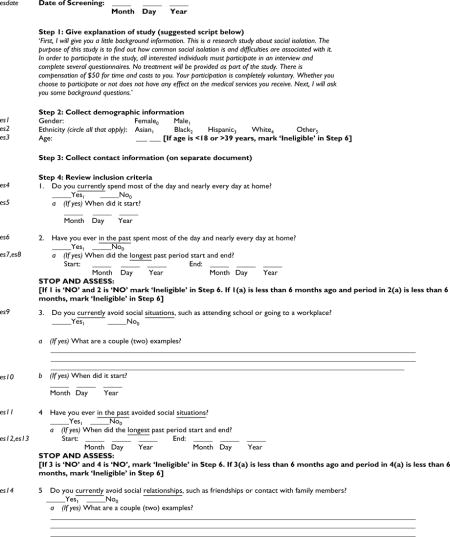

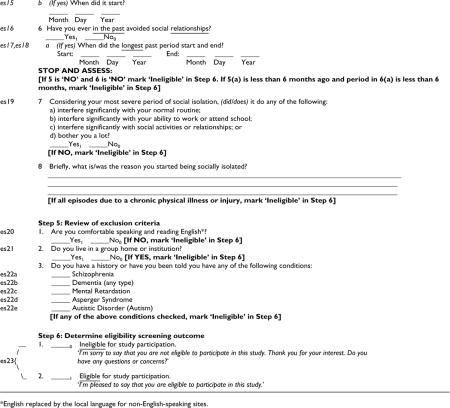

Assessment of hikikomori

Researchers administered an interview to assess for the presence of suspected hikikomori (see Appendix 1 for questionnaire), adapted from our earlier proposed definition (Teo & Gaw, 2010). We defined hikikomori as (1) spending most of the day and nearly every day at home (duration of at least 6 months); (2) avoiding social situations, such as attending school or going to a workplace (duration of at least 6 months); (3) avoiding social relationships, such as friendships or contact with family members (duration of at least 6 months); and (4) significant distress or impairment due to social isolation.

Self-report measures

We administered the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale, the Lubben Social Network Scale-6(LSNS-6), the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), the Cornell Treatment Preferences Index (CTPI) and a questionnaire on sociodemographic characteristics to participants.

The UCLA Loneliness Scale is a 20-item questionnaire that assesses how often individuals endorse subjective feelings of loneliness (e.g. ‘How often do you feel that you lack companionship?’). The score range is 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater degrees of loneliness (Russell, 1996). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale from 1 (‘never’) to 4 (‘always’). As the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale has been validated Korean and Japanese samples, it was used at these sites (Kim, 1997; Kudou & Nishikawa, 1983). At the United States and Indian sites, Version 3 of the UCLA Loneliness Scale was used. Version 3 is identical to the revised version, except for minor wording adjustments (Russell, 1996).

The LSNS-6 is a 6-item questionnaire that assesses the number of people in an individual’s social network with whom one has social contact (e.g. ‘How many relatives do you see or hear from at least once a month?’) and who are a source of social support (e.g. ‘How many friends do you feel close to such that you could call on them for help?’). There are two subscales for family and friends. The total score range is 0–30 (0–15 for each subscale), and a total score less than 12 is indicative of social isolation (Lubben et al., 2006). Such a score implies fewer than two social network members, on average, for each item. Each item is rated on a 6-point scale from 0 (‘none’) to 5 (‘nine or more’). The LSNS-6 has been validated in Korean and Japanese (Hong, Casado, & Harrington, 2011; Kurimoto et al., 2011).

The SDS is a 5-item questionnaire that assesses disability or functional impairment. The first three items evaluate level of disruption in each of three domains (work/school, social life and family life/home responsibilities) with response choices on a 0 (‘not at all’) to 10 (‘extremely’) scale, while the remaining two items evaluate days lost and days unproductive (Sheehan, 1983). Higher scores indicate more disability. The word ‘symptom’ in the SDS was replaced with ‘social isolation’ for this study. The scale has been validated in Korean and Japanese (Lee & Song, 1991; Yoshida, Otsubo, Tsuchida, Wada, & Kamijima, 2004).

The CTPI is a 6-item questionnaire that evaluates several different depression treatment preferences, including treatment modality and type of treatment provider (Raue, Schulberg, Heo, Klimstra, & Bruce, 2009). We modified the CTPI to assess preferences related to social isolation (e.g. ‘I wish to receive counseling or psychotherapy for my social isolation’). The response scale for the first five items is a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’), and the final item uses ranked treatment preferences. For the CTPI, as well as other instruments that lacked an existing translation in a target language, we translated the instrument and used back translation as verification of adequate adaption.

Statistical analysis

We compared variables using the t-test and chi-square for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. When any group or cell contained five or fewer participants, we replaced the t-test and chi-square with the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test and Fisher’s exact test, respectively. Linear regression models were used to examine the association between country and several outcome variables, including loneliness, social network and functional disability. Logistic regression models were similarly used for the association between country and the dichotomized treatment preferences. The regression models were adjusted for the effects of the educational level and age as these were significant in bivariate correlations with country. Sample sizes for particular analyses vary due to differences in number of responses. Significance level for all tests was set at p < .05 and tests were two-tailed. Data were analyzed using Stata Version 12 (Stata Corp.)

Results

Identification of hikikomori

Regarding the first aim, 36 adult participants with social withdrawal who met criteria for hikikomori were identified. The cases were found in all four countries included in this study. As seen in Table 1, the vast majority were men with varied education levels. The majority of participants lived with family members; just four (11%) lived alone. Their self-reported period of social withdrawal was on average 2.1 years.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants with hikikomori in four countries.

| Characteristic | Total

|

Japan

|

USA

|

India

|

Korea

|

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 36)

|

(n = 11)

|

(n = 11)

|

(n = 10)

|

(n = 4)

|

|||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Male | 29 (81) | 10 (91) | 7 (64) | 9 (90) | 3 (75) | .33 | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18–21 | 11 (32) | 2 (18) | 2 (18) | 3 (30) | 4 (100) | } | .04 |

| 22–30 | 11 (32) | 3 (27) | 4 (36) | 6 (60) | 0 (0) | ||

| 31–49 | 12 (35) | 6 (55) | 5 (45) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | ||

| Education level | |||||||

| High school graduate or less | 16 (44) | 7 (64) | 2 (18) | 3 (30) | 4 (100) | } | .01 |

| Some college or more | 20 (56) | 4 (36) | 9 (81) | 7 (70) | 0 (0) | ||

| Living situation | |||||||

| Lives with others | 32 (89) | 10 (91) | 8 (73) | 10 (100) | 4 (100) | } | .2 |

| Lives with no one | 4 (11) | 1 (9) | 3 (27) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Psychosocial features

We quantitatively described a number of features of individuals with hikikomori. Scores on the UCLA Loneliness Scale indicated a high level of loneliness among all participants (M = 55.4, SD = 10.5). By comparison, prior studies with normal controls in American, Indian and Korean samples have shown mean scores of about 40 (SD around 9) (Jayashankar, 2013; Lee & Lee, 2004; Russell, 1996), and studies with depressed participants have shown average scores of 49.8 (Grov, Golub, Parsons, Brennan, & Karpiak, 2010). Likewise, social networks for our sample were weak, with participants scoring a mean of 9.7 (SD = 5.7) on the LSNS-6. By comparison, prior studies with normal controls have shown average scores of 17.4 (Lubben et al., 2006). Individuals with hikikomori showed slightly higher scores on the family subscale (M = 5.4, SD = 3.0) than the friend subscale (M = 4.3, SD = 3.5). Participants with hikikomori had moderate levels of functional disability on the SDS (M = 16.5, SD = 7.9), levels comparable to patients with psychiatric disorders and more than three-fold higher than those with no mental illness in a study of a study of primary care patients (Olfson et al., 1997). Impairment was highest in terms of social life/leisure activities, compared to work/school and family life.

Treatment preferences

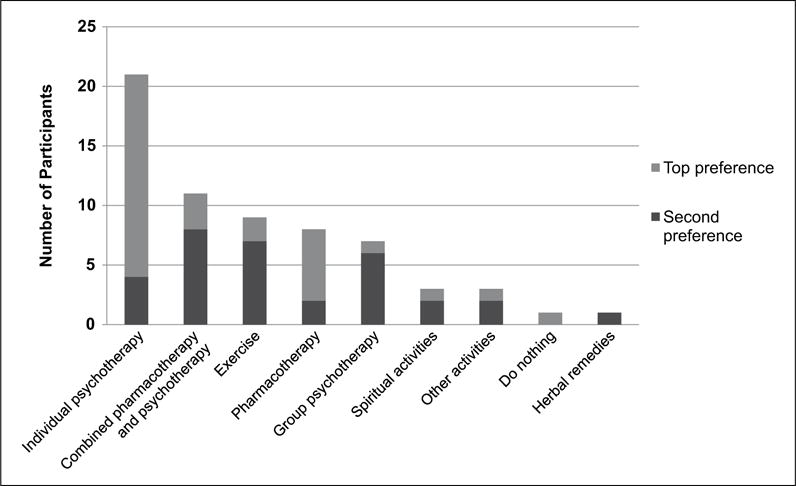

A total of 78% of the sample expressed a desire for treatment for their social withdrawal. In terms of modality of treatment, participants preferred psychotherapy (M = 3.6, SD = 1.5) over medication (M = 2.9, SD = 1.4); t(31) = 2.13, p = .04. In addition, participants also were significantly more likely to be interested in psychotherapy and medicine management delivered in-person compared to an option for provision by webcam (p < .001 for both comparisons). Participants ranked individual psychotherapy most as a desired treatment, with few desiring complementary and alternative treatments such as herbal remedies or exercise (Figure 1). As for treatment provider, participants preferred mental health specialists (M = 3.6, SD = 1.2) over primary care physicians (M = 2.7, SD = 1.2); t(34) = 3.87, p < .001.

Figure 1.

Top two treatment preferences of participants with hikikomori for their social withdrawal (n = 32).

Cross-national comparisons

We compared treatment preferences and psychosocial characteristics of participants across the four countries in this study as our exploratory aim: that is, to generate hypotheses about cross-national differences in hikikomori that might be tested in future studies. Across countries, results generally were similar. For comparison of treatment preferences across countries, the Korean sample was excluded from analyses due to small sample size (n = 4). In adjusted models controlling for age and level of education, there were no statistically significant differences in overall desire for treatment, desire for pharmacotherapy, desire for psychotherapy, interest in webcam-delivered medication management or psychotherapy, interest in in-person-delivered medication management or desire for treatment provided by a mental health professional. Participants in the United States were significantly less likely to desire treatment by a primary care physician compared to Japan (odds ratio (OR) = 0.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.00–0.60). Also, Indian participants had a significantly lower interest in in-person psychotherapy (OR = 0.00, 95% CI = 0.00–0.31). Table 2 illustrates psychosocial features of our sample of individuals with hikikomori. As illustrated by the beta coefficient, American participants demonstrated on average a 12-point higher score on the UCLA Loneliness Scale and a 4-point higher score on the family life subscale of the SDS, as compared with Japanese participants. Indian participants had significantly stronger social networks but higher levels of functional disability. Finally, Korean subjects had significantly higher levels of loneliness, weaker friendships in their social network and higher functional disability.

Table 2.

Multivariable linear regression of exploratory associations between psychosocial features of hikikomori and country.

| Japan

|

USA

|

India

|

Korea

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 11)

|

(n = 11)

|

(n = 10)

|

(n = 4)

|

||||

| Characteristic | β | β | (95% CI) | β | (95% CI) | β | (95% CI) |

| Loneliness (UCLA Loneliness Scale) | Ref | 12.35** | (5.41, 19.29) | −3.78 | (−10.90, 3.33) | 16.31** | (6.44, 26.17) |

| Social network (Lubben Social Network Scale – 6) | Ref | 0 | (−4.69, 4.68) | 5.05* | (0.24, 9.85) | −5.37 | (−12.03, 1.29) |

| Family subscale | Ref | −0.24 | (−2.77, 2.30) | 3.41* | (0.81, 6.01) | −0.86 | (−4.46, 2.75) |

| Friend subscale | Ref | 0.23 | (−2.73, 3.19) | 1.64 | (−1.40, 4.67) | −4.51* | (−8.72, −0.31) |

| Functional disability (Sheehan Disability Scale) | Ref | 4.95 | (−1.90, 11.81) | 9.04* | (2.16, 15.92) | 13.86* | (3.44, 24.27) |

| Disrupted work/school work | Ref | −0.36 | (−3.40, 2.68) | 2.20 | (−0.85, 5.25) | 1.49 | (−3.13, 6.12) |

| Disrupted social life/leisure activities | Ref | 2.04 | (−0.29, 4.36) | 2.86* | (0.48, 5.24) | 4.67* | (1.01, 8.32) |

| Disrupted family life/home responsibilities | Ref | 4.03** | (1.54, 6.52) | 4.06** | (1.51, 6.61) | 7.70*** | (3.78, 11.61) |

UCLA: University of California, Los Angeles.

Analyses controlled for age and level of education. Japan used as the reference group (Ref) for country comparisons.

statistically significant at the .05 level;

statistically significant at the .01 level;

statistically significant at the .001 level.

Discussion

This study bolsters evidence that hikikomori, as a phenotype of severe social withdrawal, exists cross-nationally. Strengths of our approach include use of a standardized definition and assessment tool for hikikomori across four countries with diverse cultures and operationalizing hikikomori with discrete questions about the frequency, length and quality of social withdrawal. Past approaches have relied on a single, complex question (Koyama et al., 2010; Umeda, Kawakami, & The World Mental Health Japan Survey Group, 2002–2006, 2012), an approach that may cause misunderstanding by placing a high cognitive burden on the respondent (Schwarz, 2007). Thus, this study offers a new interview tool to help assess for hikikomori. Our data showing loneliness and limited connections with social network members among study participants support the validity of our assessment approach to hikikomori as we have defined it.

Psychosocial features

Perhaps the most striking features of hikikomori participants in this study were high loneliness scores and impaired social network scores. Our descriptive data paint a picture of the average individual with hikikomori being intensely lonely and deficient in social support, apparently unable to maintain meaningful social ties. This is despite rarely living alone and indicating a desire for treatment of their social withdrawal.

Treatment preferences

In these individuals who have been avoided social contact for such a prolonged period of time, we were surprised to find a consistent preference for treatment delivered in-person, as opposed to telepsychiatry-style. We believe this is the first study to describe treatment preferences in a sample of individuals with hikikomori. Understanding treatment preferences is a valuable first step for intervention research, particularly in light of evidence that treatment response rates for hikikomori are low (Nagata et al., 2013). Individuals with hikikomori may feel ambivalent about their desire for social relationships, and a patient–provider relationship may offer an entry point into re-establishing social connections. Given these results, future intervention studies for hikikomori might consider evaluating home visitation, particularly when conducted by a mental health professional and with an aim of boosting the social support of hikikomori patients (Dickens, Richards, Greaves, & Campbell, 2011; Lee et al., 2013). Other interventions that have shown promise in populations with mental illnesses and are thought to work by bolstering social relationships, such as peer support, might be investigated (Pfeiffer, Heisler, Piette, Rogers, & Valenstein, 2011; Proudfoot et al., 2012).

Limitations

This study was designed as a case series, and therefore several limitations in interpretation of the results bear note. First, our sample was small, but we have employed statistical methods that adjust for sample size. Second, cross-national comparisons should only be regarded as exploratory because different recruitment methods were used across countries, data harmonization across cultures is always imperfect and adjustment for potential confounders was limited to basic sociodemographic variables. Third, individuals with hikikomori who are able to participate in a research study such as this are unlikely to be representative of all of those with hikikomori. In particular, individuals with hikikomori are often perceived as resistant to undergo treatment, and our sample may represent those who have milder symptoms or begun recovery. Nonetheless, this highlights a group that may represent great opportunity for intervention. Fourth, as this was primarily a descriptive study, no comparison group was included, though we have included comparisons with normative data for selected measures. Finally, the CTPI has not been validated in international samples, and therefore treatment preference data must be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusion

In sum, this study suggests that hikikomori exists cross-nationally, can be assessed with a brief interview tool and is associated with substantial loneliness, impaired social networks, disability and desire for treatment. Results of our study suggest several possible directions for future research. First, we believe future cross-national studies of hikikomori should obtain larger samples, which could be achieved by focusing on just two locations for comparison. Another approach would be to compare hikikomori participants to a control group such as participants with social anxiety disorder to help tease out differences between hikikomori and other conditions. Although it was beyond the scope of this study to conduct formal psychometric testing on our hikikomori assessment tool, future research on the reliability and validity of the hikikomori diagnostic interview would be helpful. Furthermore, development and testing of a hikikomori scale could help with conceptual clarity (e.g. constructs associated with hikikomori) and distinction from related conditions such as social anxiety disorder. Once validated, a hikikomori scale or diagnostic interview could then be applied to research on the prevalence and detection of hikikomori. To reach a more representative sample including individuals unable to leave their residence under any circumstance, Internet-based surveys on hikikomori should be developed. Finally, interventions that account for patient preference might be tested.

Acknowledgments

At the time this study was completed, Dr. Teo was affiliated with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the World Psychiatric Association and Pfizer Health Research Foundation (grant no. 12-2-038).

Appendix 1

Footnotes

This study was presented in part at the Society for the Study of Psychiatry and Culture Annual Meeting in Toronto, Canada, on 4 May 4 2013.

References

- De Michele F, Caredda M, Delle Chiaie R, Salviati M, Biondi M. Hikikomori (ひきこもり): A culture-bound syndrome in the web 2.0 era. Rivista di Psichiatria. 2013;48:354–358. doi: 10.1708/1319.14633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:647. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuhashi T, Figueiredo C, Pionnié-Dax N, Fansten M, Vellut N, Castel PH. Pathology seen in French “Hikikomori”. Seishin shinkeigaku zasshi = Psychiatria et neurologia Japonica. 2012;114:1173–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuhashi T, Suzuki K, Teruyama J, Sedooka A, Tsuda H, Shimizu M, Castel PH. Commonalities and differences in hikikomori youths in Japan and France. Nagoya Journal of Health, Physical Fitness & Sports. 2011;34(1):29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Campayo J, Alda M, Sobradiel N, Sanz Abos B. A case report of hikikomori in Spain. Medicina Clinica (Barc) 2007;129:318–319. doi: 10.1157/13109125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care. 2010;22:630–639. doi: 10.1080/09540120903280901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Casado BL, Harrington D. Validation of Korean versions of the Lubben Social Network Scales in Korean Americans. Clinical Gerontologist. 2011;34:319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Jayashankar Study on personality and loneliness among the students of IIT Hyderabad. IDP Poster Presentation. Lecture conducted from Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad, India 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Kato TA, Tateno M, Shinfuku N, Fujisawa D, Teo AR, Sartorius N, Kanba S. Does the “hikikomori” syndrome of social withdrawal exist outside Japan? A preliminary international investigation. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012;47:1061–75. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0411-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim OS. Korean version of the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Reliability and validity test. The Journal of Nurses Academic Society. 1997;27:871–879. [Google Scholar]

- Koyama A, Miyake Y, Kawakami N, Tsuchiya M, Tachimori H, Takeshima T. Lifetime prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity and demographic correlates of ‘hikikomori’ in a community population in Japan. Psychiatry Research. 2010;176:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg A, Dickie JR. Attachment and hikikomori: A psychosocial developmental model. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2013;59(1):61–72. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudou R, Nishikawa M. Kaiteiban UCLA kodokukun shakudo [The study for loneliness: Assessment of reliability and validity of the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale] Experimental Social Psychological Research. 1983;22:99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kurimoto A, Awata S, Ohkubo T, Tsubota-Utsugi M, Asayama K, Takahashi K, Imai Y. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi/Japanese Journal of Geriatrics. 2011;48:149–157. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.48.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Lee SH. Depression, loneliness, impulsiveness, sensation-seeking and self-efficacy of adolescents with cybersexual addiction. The Korea Journal of Counseling. 2004;12:145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Lee JY, Choi TY, Choi JT. Home visitation program for detecting, evaluating, and treating socially withdrawn youth in Korea. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2013;67:193–202. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Song J. A study of the reliability and the validity of the BDI, SDS, and MMPI-D Scales. Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991;10:98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, Iliffe S, Kruse WVR, Beck JC, Stuck AE. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:503–513. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Tost H. Neural mechanisms of social risk for psychiatric disorders. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15:663–668. doi: 10.1038/nn.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Yamada H, Teo AR, Yoshimura C, Nakajima T, van Vliet I. Comorbid social withdrawal (hikikomori) in outpatients with social anxiety disorder: Clinical characteristics and treatment response in a case series. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2013;59:73–78. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Fireman B, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Sheehan DV, Kathol RG, Farber L. Mental disorders and disability among patients in a primary care group practice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1734–1740. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer PN, Heisler M, Piette JD, Rogers MA, Valenstein M. Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: A meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2011;33:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot JG, Jayawant A, Whitton AE, Parker G, Manicavasagar V, Smith M, Nicholas J. Mechanisms underpinning effective peer support: A qualitative analysis of interactions between expert peers and patients newly-diagnosed with bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:196. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue PJ, Schulberg HC, Heo M, Klimstra S, Bruce ML. Patients’ depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: A randomized primary care study. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:337–343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;66:20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K. Hikikomori no hyouka shien ni kansuru gaidorain [Guideline on evaluation and support of hikikomori] Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto N, Martin RG, Kumano H, Kuboki T, Al-Adawi S. Hikikomori, is it a culture-reactive or culture-bound syndrome? Nidotherapy and a clinical vignette from Oman. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2005;35:191–198. doi: 10.2190/7WEQ-216D-TVNH-PQJ1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2007;21:277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV. Sheehan disability scale. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tateno M, Park TW, Kato TA, Umene-Nakano W, Saito T. Hikikomori as a possible clinical term in psychiatry: A questionnaire survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo AR. Social isolation associated with depression: A case report of hikikomori. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2013;59:339–341. doi: 10.1177/0020764012437128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo AR, Gaw AC. Hikikomori, a Japanese culture-bound syndrome of social withdrawal? The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198:444–449. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e086b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda M, Kawakami N, The World Mental Health Japan Survey Group, 2002–2006 Association of childhood family environments with the risk of social withdrawal (“hikikomori”) in the community population in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2012;66:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J. Public health experts concerned about “hikikomori”. The Lancet. 2002;359:1131. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Otsubo T, Tsuchida H, Wada Y, Kamijima K. Reliability and validity of the Sheehan Disability Scale-Japanese Version. Rinsyoseishinyakuri. 2004;7:1645–1653. [Google Scholar]