Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to implement a public film event about mental health aspects of social withdrawal. Secondary aims were to assess participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and intended behaviors related to social withdrawal.

Method

The event, held at three U.S. sites, consisted of a film screening, question-and-answer session, and lecture. Participants completed a post-event survey.

Results

Of the 163 participants, 115 (70.6%) completed surveys. Most of the sample deemed social withdrawal a significant mental health issue. Regarding post-event intended behaviors, 90.2% reported intent to get more information, 48.0% to being vigilant for social withdrawal in others, and 19.6% to talking with a health care professional about concerns for social withdrawal in themselves or someone they knew. Asian participants were significantly more likely than non-Asians to intend to encourage help-seeking for social withdrawal (p = .001).

Discussion

A public film event may be a creative way to improve mental health awareness and treatment-seeking.

Keywords: culture, film, Japan, multimedia, social isolation, social psychiatry

Introduction

Film is the general public’s primary source of information on mental illnesses (Nairn et al., 2011). However, the portrayal of mental illness in film through time has ranged from the grossly inaccurate and stigmatizing to the clinically astute and benevolent. On one hand, film portrayals that “perpetuate popular mythologies” (Cape, 2003) and are “blurred with populists’ misinterpretation” (Damjanović et al., 2009) are pervasive. On the other hand, film and other multimedia events may be used in beneficial ways such as in medical education (Rosenstock, 2003; Alexander et al., 2005; Masters, 2005; Kalra, 2012), antistigma efforts (Kerby et al., 2008), and promoting awareness of the importance of early intervention and prevention (Bird and Marti, 2009).

Mental health access and treatment seeking appears to be a particularly challenging issue in Asian and Asian-American populations. Asian-Americans express greater shame and embarrassment about having a mental illness and greater difficulty in seeking or engaging in mental health treatment than non-Latino Whites (Jimenez et al., 2013). Reports have highlighted how Asian-Americans face barriers to help seeking of mental health treatment services, and these barriers include cognitive, affective, and value-based differences from other populations (Leong and Lau, 2001). Instead, Asians may be more likely to value and seek assistance for mental health concerns through their social network (Narikiyo and Kameoka, 1992) (Mojaverian et al., 2012).

One newly recognized psychiatric problem that has emerged from Japan is a severe form of social withdrawal or social isolation called hikikomori (Teo and Gaw, 2010; Tateno et al., 2012). The core feature of hikikomori is spending almost all time confined to the home and includes marked avoidance of social situations and relationships for at least 6 months (Teo and Gaw, 2010; Tateno et al., 2012). Concern about hikikomori stems from its prevalence (Koyama et al., 2010), high level of psychiatric comorbidity and functional impairment (Kondo et al. 2007; Kondo et al., 2011; Nagata et al., 2013), and growth beyond Japan’s borders (Garcia-Campayo et al. 2007; Furuhashi et al. 2011; Kato et al., 2011; Teo, 2012; Lee et al., 2013). Treatment seeking is markedly delayed, with first presentation, on average, over 3 years after symptom onset (Kondo et al., 2011).

The primary aim of this project was to implement a community-based event consisting of both a film screening and lecture to promote public awareness about social withdrawal, and specifically hikikomori, as a mental health problem. Secondary aims were to assess event attendees’ knowledge, attitudes, and intended behaviors related to hikikomori and determine if these domains differed depending on the ethnic background of attendees.

Methods

Program description

We developed a multipart event to provide several perspectives and viewpoints on the hikikomori syndrome of social withdrawal, and the event was held three times in three locations in the midwestern United States. The three events each had three components: a lecture, a film screening, and a question-and-answer session. A 45-minute lecture on the topic of hikikomori was delivered by a physician-researcher, psychiatrist, and content expert in hikikomori (A. R. T.). The lecture content was designed to be understandable to a general public audience and covered the definition of hikikomori, clinical features, epidemiology, etiology, and treatment considerations. The film was called Left-Handed (http://tobiranomuko.com/), a 110-minute feature film that tells the story of a Japanese family and their teenage son who goes into a 2-year-long period of social withdrawal. The film is in Japanese with English subtitles and, although fictional, stars a young man who actually had a prior history of hikikomori. A question-and-answer session accompanied the lecture and film, and audience members were encouraged to ask questions and share comments related to the film and/or lecture. At one event, the film director and producer served as panelists, and at the two other events, the lecturer (A. R. T.) responded to questions. All three events were held in sequence, for a total length of approximately 3 hours. Events were free to participants; they were funded and promoted broadly by the local university’s Asian studies center using flyers, e-mails, and Web site announcements. Preevent inquires received by event staff were transcribed and recorded as qualitative data.

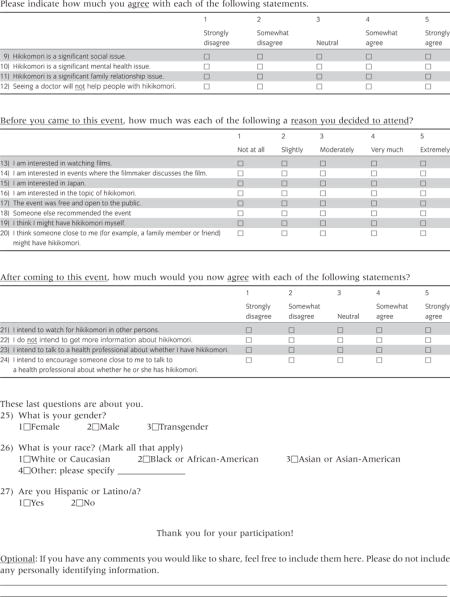

Questionnaire

We developed a brief questionnaire in English to assess knowledge, attitudes, intended behavior, and motivations related to hikikomori (see Appendix I). We conducted six cognitive interviews to test questionnaire items (Groves, 2009), and these responses informed questionnaire revisions. The questionnaire was administered immediately after the screening of the film and discussion period. Questions were framed with a preface such as “After coming to this event, ….” to assist with identifying effects of the event on the respondent. Four knowledge items each contained a statement (e.g., “Hikikomori is often associated with conflict with family relationships”), and response choices consisted of “agree” and disagree.” Four items focused on attitudes towards hikikomori (e.g., “Hikikomori is a significant social issue”), and four items inquired about postevent intended behaviors (e.g., “I intend to watch for hikikomori in other persons”); in both cases, response choices were a five-point Likert scales ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Eight items addressed reasons for attending the event (e.g., “I am interested in watching films”) with a five-point response scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely.” Basic demographic items were also included, as well as an optional, open-ended written comments section. The questionnaire was anonymous, limited to audience members age 18 and older, and the study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Michigan.

Analysis

Regarding quantitative data, after analyzing the distribution of responses for each variable, we dichotomized all variables with a five-point response scale and analyzed them as categorical variables as distributions were nonnormal. For comparisons between Asian and non-Asian participants, we employed t-tests and chi-square for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Significance level for all tests was set at P < 0.05, and tests were two-tailed. Data were analyzed using Stata Version 12 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas).

Text data from open-ended written comments on the questionnaire were analyzed qualitatively. Comments were coded independently by two research staff members. Coders categorized comments into one of nine categories. In instances in which the coders disagreed, a third coder (A. R. T.) facilitated discussion to reach consensus and adjudicated any differences. Coded written comments were then categorized into those from Asian/Asian-American participants and those from non-Asian/Asian-Americans.

Results

Description of sample

Of 163 attendees at the events (128 in Ann Arbor, MI, 18 in Cleveland, OH, and 17 in Columbus, OH), 115 completed surveys for a response rate of 70.6%. Ten respondents were excluded from analysis due to responding that they did not attend the event or not answering whether they attended the event, leaving a sample of 105 respondents for analysis. On average, our sample was 40.8 years old (SD = 15.9 years), 57.8% female, 45.1% white, 45.1% Asian or Asian-American, and 7.8% black. There were no statistically significant differences between Asian and non-Asian participants in age or gender.

Attitudes and intended behaviors related to hikikomori

The vast majority of the overall sample deemed hikikomori a significant mental health (90.1%), social (84.2%), and family relationship issue (81.0%). They also felt seeing a doctor would help a person with hikikomori (89.8%). In terms of postevent intended behaviors, 48.0% stated that they intended to be vigilant for hikikomori in others, and the vast majority (90.2%) intended to get more information. Three participants (2.9%) stated concern about having hikikomori themselves as a reason for attending; while, after having attended the event, seven (6.9%) intended to talk to a health professional about concerns for having hikikomori themselves. Thirteen (12.7%) intended to talk to a health professional about concerns for someone they knew having hikikomori. Qualitative data from preevent inquiries corroborated the value of the event for people concerned about social withdrawal in their loved ones. For instance, one couple reported driving 5 hours to attend the event, and another woman with a withdrawn son requested lecture materials to “give me some ideas why he is the way he is.”

Comparison of Asian/Asian-American and non-Asian participants

Asian and Asian-American participants differed from non-Asians in several important dimensions (see Table 1). Asians and Asian-Americans were more likely than non-Asians to cite interest in the topic of hikikomori (χ2[1, n = 96] = 4.22, P = .04), the event being free and open to the public (χ2[1, n = 95] = 7.45, P = .006), and thinking someone close to them might have hikikomori (χ2[1, n = 96] = 5.44, P = .02) as reasons for attending the event. In terms of knowledge about hikikomori, Asian and Asian-American participants were less likely to know that hikikomori affects the ability of the individual to function at work or school (χ2[1, n = 93] = 8.13, P = .004). An Asian participant commented, “I was not aware of this form of mental illness but glad to learn.” In terms of attitudes about hikikomori, Asian and Asian-American participants were less likely to believe that seeing a doctor would help a person with hikikomori (χ2[1, n = 96] = 9.70, P = .002). However, Asian and Asian-American participants were more likely to say they “intend to encourage someone close to me to talk to a health professional about whether he or she has hikikomori” (χ2[1, n = 95] = 10.55, P = .001). Likewise, one Asian respondent commented regarding treatment, “I think it is very important to share hikikomori with more people. There [is a] need to establish support groups.”

Table 1.

Knowledge, attitudes, and intended behaviors of film event participants

| Race

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian (n = 46)

|

Non-Asian (n = 56)

|

||||

| n | % | n | % | P | |

| Knowledge statements (correct responses) | |||||

| The main character in the movie has hikikomori | 44 | 100 | 55 | 100 | na |

| Hikikomori is a form of social isolation or social withdrawal† | 41 | 93.2 | 52 | 94.5 | 0.78 |

| Hikikomori affects the ability of the person who has it to go to school or work† | 35 | 85.4 | 52 | 100.0 | <0.01* |

| Hikikomori is often associated with conflict with family relationships | 25 | 56.8 | 33 | 64.7 | 0.43 |

| Attitudes toward hikikomori | |||||

| Hikikomori is a significant… | |||||

| Mental health issue | 37 | 86.0 | 52 | 94.5 | 0.15 |

| Social issue | 37 | 86.0 | 46 | 83.6 | 0.74 |

| Family relationship issue | 33 | 78.6 | 46 | 83.6 | 0.53 |

| Seeing a doctor will help people with hikikomori† | 33 | 78.6 | 53 | 98.2 | <0.01* |

| Postevent intended behaviors | |||||

| Get more information about hikikomori† | 40 | 93.0 | 52 | 92.9 | 0.98 |

| Watch for hikikomori in others | 20 | 47.6 | 29 | 51.8 | 0.68 |

| Talk to a health professional, for other | 11 | 26.8 | 2 | 3.7 | <0.01* |

| Talk to a health professional, for self | 4 | 9.5 | 3 | 5.5 | 0.44 |

= significant P-value.

= Reverse-coded from original item.

Knowledge statements were presented as true/false questions. For attitudes and intended behaviors, subjects were asked to respond with how much they agreed with each statement. On a five-point scale, responses of 4 “very much” or 5 “extremely” are reported. Number of responses for individual items varies; percentages based on number of valid responses.

na, not applicable.

Discussion

Our event format – which targeted the general public and combined a lecture, film screening, and question-and-answer session – has rarely been described in the literature. Programs that have combined a didactic element with a film screening almost exclusively have been reported for use in medical education (Kalra, 2011, 2012). More typically, films are screened without any additional component (Kerby et al., 2008; Quinn et al., 2011). Thus, our event format appears relatively unique in the literature.

We suspect a multipart event format, although unique in the literature, is actually utilized much more than reported. Indeed, we are aware of two other recent but unpublished local events about bipolar disorder, one a theatrical play and another a documentary, both with panel question-and-answer sessions.

By and large, Asian and non-Asian participants displayed similar characteristics. That is, on the majority of items assessed regarding reasons for attending the event, knowledge, attitudes, and intended behaviors there were no statistically significant differences. That said, one particular difference of note between the Asian and non-Asian groups was that Asians had higher intention to utilize professional mental health services than non-Asians. Thus, an intervention incorporating components of our event might be successful in enhancing mental health access among Asian and Asian-American groups. Such an effect is supported by a systematic review and meta-analysis that suggested public understanding of mental illness has been associated with greater acceptance of professional psychiatric treatment (Schomerus et al., 2012).

There are several important limitations to this study. Data were all based on self-report, without any prepost or follow-up comparisons of participants. Therefore, whether participants actually changed behaviors or attitudes as a result of the event cannot be answered by this study. Moreover, event participation was completely voluntary, and a selection bias toward those with interest and more accepting attitudes toward mental health issues was likely present. Finally, because we prioritized obtaining a higher response rate, our brief survey excluded questions that would have helped obtain a more nuanced analysis. Specifically, our categorization of Asian/Asian-American versus non-Asian does not allow precise ethnic comparisons, and it is impossible to know from this study what the “active ingredient(s)” to a lecture/film/discussion-based intervention is because we did not discretely evaluate the effect of each event component.

To advance research in the rarely studied area of film for mental health services promotion, we suggest two opportunities for future studies. First, participants should be surveyed before and after the event, with the latter ideally occurring some time after the event has concluded to assess for durability of any effects. Second, studies could assess the impact of each feature of the event (e.g., film screening versus question-and-answer session). This might be accomplished by qualitative interviews with event participants or quantitative comparisons of events with and without each add-on component.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Joanna Rew for assistance with literature review and qualitative data analysis. We also acknowledge the University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies and the Institute for Japanese studies at the Ohio State University for support of the events.

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Appendix I: Left-Handed film event survey

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors report no competing interests.

Previous presentations: None.

References

- Alexander M, et al. Cinemeducation: A Comprehensive Guide to Using Film in Medical Education. Radcliffe Publishing; Oxford, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bird L, Marti J. Red carpet reception for inaugural IEPA Short Film Festival. Early Intervent Psychiatry. 2009;3(1):3–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2009.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cape GS. Addiction, stigma and movies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107(3):163–169. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanović A, Vuković O, Jovanović AA, Jasović-Gasić M. Psychiatry and movies. Psychiatr Danub. 2009;21(2):230–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuhashi T, Suzuki K, Teruyama J, et al. Commonalities and differences in hikikomori youths in Japan and France. Nagoya J Health Phys Fitness Sports. 2011;34(1):29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Campayo J, Alda M, Sobradiel N, Sanz Abos B. A case report of hikikomori in Spain. Med Clin (Barc) 2007;129:318–319. doi: 10.1157/13109125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM. Survey Methodology. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez DE, Bartels SJ, Cardenas V, Alegria M. Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among racial/ethnic older adults in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(10):1061–1068. doi: 10.1002/gps.3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra G. Teaching diagnostic approach to a patient through cinema. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22(3):571–573. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra G. Talking about stigma towards mental health professionals with psychiatry trainees: a movie club approach. Asian J Psychiatry. 2012;5(3):266–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato TA, Tateno M, Shinfuku N, et al. Does the “hikikomori” syndrome of social withdrawal exist outside Japan? A preliminary international investigation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;47(7):1061–1075. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0411-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerby J, Tateno M, Shinfuku N. Anti-stigma films and medical students’ attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatry: randomised controlled trial. Psychiatr Bull. 2008;32(9):345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N, Kiyota Y, Kitahashi Y. Psychiatric background of social withdrawal in adolescence. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2007;109(9):834–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo N, Sakai M, Kuroda Y, Kiyota Y, Kitabata Y, Kurosawa M. General condition of hikikomori (prolonged social withdrawal) in Japan: psychiatric diagnosis and outcome in mental health welfare centres. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;59(1):79–86. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama A, Miyake Y, Kawakami N, Tsuchiya M, Tachimori H, Takeshima T. Lifetime prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity and demographic correlates of “hikikomori” in a community population in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(1):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Lee JY, Choi TY, Choi JT. Home visitation program for detecting, evaluating, and treating socially withdrawn youth in Korea. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:193–202. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong FT, Lau AS. Barriers to providing effective mental health services to Asian Americans. Ment Health Serv Res. 2001;3(4):201–214. doi: 10.1023/a:1013177014788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters JC. Hollywood in the classroom: using feature films to teach. Nurse Educ. 2005;30(3):113–116. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200505000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojaverian T, Hashimoto T, Kim HS. Cultural differences in professional help seeking: a comparison of Japan and the U.S. Front Psychol. 2012;3:615. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Teo AR, Yoshimura C, Nakajima T, van Vliet I. Comorbid social withdrawal (hikikomori) in outpatients with social anxiety disorder: clinical characteristics and treatment response in a case series. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59(1):73–78. doi: 10.1177/0020764011423184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn R, Coverdale S, Coverdale JH. A framework for understanding media depictions of mental illness. Acad Psychiatry. 2011;35(3):202–206. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.35.3.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narikiyo TA, Kameoka VA. Attributions of mental illness and judgments about help seeking among Japanese-American and White American students. J Couns Psychol. 1992;39(3):363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn N, Shulman A, Knifton L, Byrne P. The impact of a national mental health arts and film festival on stigma and recovery. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123(1):71–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock J. Beyond a beautiful mind: film choices for teaching schizophrenia. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27(2):117–122. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Schwahn C, Holzinger A, Corrigan PW, Grabe HJ, Carta MG, Angermeyer MC. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(6):440–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateno M, Park TW, Kato TA, Umene-Nakano W, Saito T. Hikikomori as a possible clinical term in psychiatry: a questionnaire survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo AR. Social isolation associated with depression: a case report of hikikomori. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;59(4):339–341. doi: 10.1177/0020764012437128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo AR, Gaw AC. Hikikomori, a Japanese culture-bound syndrome of social withdrawal? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(6):444–449. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e086b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]