Abstract

Sexual risk among older adults (OAs) is prevalent, though little is known about the accuracy of sexual risk perceptions. Thus, the aim was to determine the accuracy of sexual risk perceptions among OAs by examining concordance between self-reported sexual risk behaviors and perceived risk. Data on OAs aged 50 to 92 were collected via Amazon Mechanical Turk. Frequency of sexual risk behaviors (past 6 months) were reported along with perceived risk (i.e., STI susceptibility). Accuracy categories (accurate, underestimated, overestimated) were established based on dis/concordance between risk levels (low, moderate, high) and perceived risk (not susceptible, somewhat susceptible, very susceptible). Approximately half of the sample reported engaging in vaginal (49%) and/or oral sex (43%) without a condom in the past 6 months. However, approximately two-thirds of the sample indicated they were “not susceptible” to STIs. No relationship was found between risk behaviors and risk perceptions, and approximately half (48.1%) of OAs in the sample underestimated their risk. Accuracy was found to decrease as sexual risk level increased, with 93.1% of high risk OAs underestimating their risk. Several sexual risk behaviors are prevalent among OAs, particularly men. However, perception of risk is often inaccurate and warrants attention.

Keywords: sexual risk, perceived risk, sexually transmitted infections, aging

Older adult (OA) sexual health deserves attention, as sexual well-being is identified as important to OAs (Fisher, 2010), and sexually transmitted infection (STIs) rates have increased steadily. Approximately 11% of new HIV infections annually in the United States are among adults aged 50+ (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2015). In 2011, 26% of people with HIV were aged 55+ (CDC, 2015), with various aging communities reporting exponential increases in STIs such as chlamydia and syphilis (e.g., Phoenix 87% and central Florida 71% increase from 2005 to 2009) (Johnson, 2013). Further, diagnoses in OAs tend to occur later in the disease course (e.g., HIV), and as age at diagnosis increases, survival rates decline (Brooks, Buchacz, Gebo, & Mermin, 2012). Several biopsychosocial factors contribute to risky sexual behaviors and increasing STI rates among OAs, including underestimating sexual risk, which may undermine protective behaviors. This study examined estimations of sexual risk and their accuracy by providing information on actual and perceived sexual risk among OAs aged 50 to 92.

Sexual Risk among Older Adults in the United States

Older adults are often viewed as asexual; however, they do engage in both safe and risky sexual behavior (Lindau et al., 2007; Schick et al., 2010). Risk behaviors reported in the literature include condom use, sexual partners, and STI testing. The current review of sexual risk in OAs was limited to those who are community-dwelling; however for a review of studies among HIV-positive OAs see Pilowsky and Wu (2015).

Condom use

The majority of aging sexual risk literature focuses solely on condom use, and shows that OA condom use rates are consistently low across gender, race, relationship status, and cohort (Fisher, 2010; Glaude-Hosch et al., 2015; Schick et al., 2010). Using National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) data, Schick and others (2010) examined condom use during the most recent sexual encounter among persons 50+ with multiple sexual partners (n = 203). Twenty percent of men and 24% of women reported condom use at last sexual encounter, similar to reported rates of condom use among men (24.7%) and women (21.8%) aged 18–94 (Reece et al., 2010). In a study by American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) on a national probability sample of community-dwelling OAs, 8% of respondents who were sexually active in the past month reported using condoms “all the time”, and another 4% reported condom use “usually, but not all the time” (Fisher, 2010). Using the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) data, Glaude-Hosch and colleagues (2015) reported even lower rates of condom use (97% never used condoms in the past year). However, they included both sexually active and inactive community-dwelling OAs in their analyses, with 50.7% of the sample reporting no sexual behaviors, which likely affected such low condom usage rates. A review of studies conducted with racial/ethnically diverse older women with ages ranging from 50 to 81 found that condom use was infrequent and knowledge of the protective efficacy of condoms was low (Smith & Larson, 2015). Studies cited several reasons for low condom use among diverse older women, including lower education and income levels, low perceived risk, lower condom use self-efficacy, and history of interpersonal violence.

Sexual partners

The mid- to late-adulthood transition is associated with many relationship changes (e.g., divorce, widowhood), which may lead to increased risk for STIs (Sherman, Harvey, & Noell, 2005). New relationships may have unique challenges for older women, as historical influences such as power loss in heterosexual relationships may complicate sexual negotiations (Durvasula, 2014). Approximately 12% of a national sample of OAs (Fisher, 2010) reported that they were unmarried and dating, and another 18% reported that they were interested in dating. Mairs and Bullock (2014) studied dating behaviors in a sample of Canadians (50+) who wintered in Florida (“snowbirds”) (n = 55). Almost one-half (47.3%) dated in Florida only and 12.7% dated in both locations, suggesting that “snowbirds” may have engaged in relationships that were temporary and casual. Of those who dated, just over 75% reported having sex with their dating partner and approximately 14% reported consistent condom use. Few studies on community-dwelling OAs report data on multiple sexual partners, a significant sexual risk factor given the low rates of safe sex reported by OAs. One study concluded that 4% of their sexually active and inactive community-dwelling OA sample had multiple sexual partners (Fisher, 2010).

STI testing

STI and HIV testing rates for OAs are often low, with significantly lower proportions of OAs having recent or lifetime testing when compared to those ages 49 and younger (Ford et al., 2015). Schick et al. (2010) found that 64.4% of OA sexually active women, and 68.9% of OA sexually active men in their study had not been tested for STIs within the past year; 5% of that sample reported their most recent sexual partner had an STI. Sormanti and Shibusawa (2007) reported that 45% (n = 272) of sexually active women with a primary sexual partner in their sample of urban middle-aged women had been tested for HIV. Four percent of those tested reported being HIV positive (n = 11). Of note, 5% of OA women in primary sexual relationships reported having a relationship with another man within two years. The “snowbird” study found that 73% of their 265 participants had never been tested for HIV, and 9.1% were unsure whether they had been tested (Mairs & Bullock, 2014).

Risk Factors for STIs among Older Adults

Several interrelated biopsychosocial explanations exist for sexual risk and STIs among OAs. Biological factors such as decreased immune functioning due to chronic illness (e.g., diabetes, cancer), leave the body susceptible to infection (Brooks et al., 2012). Physiological changes, such as decreased estrogen, may directly or indirectly increase risk for infection (Johnson, 2013). Psychosocial changes (e.g., divorce, ageism) can also increase risk for STIs and may exacerbate the effects of HIV/AIDS and other STIs if testing and treatment are delayed (Roger, Mignone, & Kirkland, 2013). For instance, OA sexual stigma has contributed to – and is reinforced by – the lack of STI testing guidelines. Current CDC HIV testing recommendations for universal (opt-out) testing ends at age 64. Those aged 65 or older are screened based on thorough sexual risk assessment (Brooks et al., 2012); however, research indicates a lack of sexual health discussions between physicians and OAs (Glaude-Hosch et al., 2015; Ports, Barnack-Tavlaris, Syme, Perera, & Lafata, 2014). Without those discussions, thorough risk assessment is likely not conducted, and at-risk OAs may not be referred for HIV and/or STI testing.

Socio-historical context also influences OA sexual risk. Sherrard and Wainwright (2012) postulate that adults aged 60+ were teenagers in the 1960s–1970s with the advent of oral contraceptives, decriminalization of homosexuality, and more liberal views of sexual conduct. Further, adults aged 60+ were in their 30s and 40s in when HIV/AIDS epidemic began in the US. Stereotypes associated with HIV/AIDS (“gay disease”, affects the promiscuous) may have prevented heterosexual and “monogamous” couples from perceiving HIV/AIDS as a relevant problem. Thus, messages about STI prevention (particularly HIV) and the importance of condom use, have failed to target this cohort. This is evidenced by the lower levels of knowledge about HIV/STI prevention reported among OAs compared to younger cohorts (Maes & Louis, 2003; Orel et al., 2005). Older adults—women in particular—have adequate to good general HIV knowledge (e.g., transmission likelihood; Durvasula, 2014; Hillman, 2007), but they may lack specific information (e.g., age-specific risk, protective role of condoms) and interest in HIV education varies by cohort (Akers, Bernstein, Henderson, Doyle, & Corbie-Smith, 2007; Orel et al., 2005; Sankar et al., 2011). Empirical studies linking STI knowledge deficits directly to OA sexual risk behavior are few, with one study with a small sample of community-dwelling OAs failing to find a relationship between knowledge and risk behavior (Maes & Louis, 2003).

Perceived risk and accuracy

Individuals often underestimate or misperceive their sexual risk, with studies on OAs suggesting they have low perceived sexual risk (Glaude-Hosch et al., 2015; Jackson et al., 2005; Prati et al., 2015; Ward et al., 2011), particularly when compared to younger cohorts (Ford et al., 2015). One study found African American OAs were more likely to perceive themselves at risk for HIV than non-Hispanic White OAs (Glaude-Hosche et al., 2015). Results have been mixed on gender differences in perceived risk (Hillman, 2007; Maes & Louis, 2003; Prati et al., 2015) with some indication that older women perceive themselves at higher risk for HIV/AIDS than older men (Prati et al., 2015). Notably, each of these studies examined perception of HIV/AIDS risk as opposed to general STI risk in OAs.

Several health behavior theories implicate the discrepancy between perceived and actual risk as detrimental to health behavior change/maintenance (Janz & Becher, 1984). Research has concluded that recognition of risky sexual behavior is necessary for behavior change (Catania, Kegeles, & Coates, 1990). Further, it is not simply perceived risk, but rather accurate perceptions of sexual risk that are “necessary but not sufficient” for reducing sexual risk behavior (Kershaw et al., 2003, p. 523; Orel et al., 2005). Thus, higher actual sexual risk corresponds to higher perceived risk (accuracy hypothesis), and this accuracy aids in developing the intention to reduce sexual risk (behavioral motivation hypothesis). Conversely, inaccuracies in risk perception (underestimating risk) may lead to lack of behavior change (Brewer et al., 2004).

The accuracy of perceived sexual risk is rarely empirically tested. One study on a clinical sample of sexually active female adolescents (aged 14–19) found a positive relationship between actual and perceived sexual risk (r = .32), suggesting an accuracy trend (Kershaw et al., 2003). After further classifying participants as having either accurate, underestimated, or overestimated sexual risk by comparing reports of actual (condom use, risky partner, STI diagnosis) and perceived risk (single continuous item), the discordance between actual and perceived sexual risk emerged, with approximately half of participants (51%) underestimating their risk. Additionally, a study on a random, national sample aged 18–49 examined perceived and actual HIV risk, also finding a significant positive relationship (r = .32).

A few studies indirectly assessed the discrepancy between perceived and putative sexual risk among OAs. Jackson and colleagues (2005) studied a small sample of African American OAs, and 63.2% of the sample reported “low” chances of contracting HIV, even though the majority of OA men with multiple sexual partners reported no condom use. Additionally, a study in a small sample of OAs (n = 166; Maes & Louis, 2003) found low rates of perceived susceptibility/risk for HIV/AIDS (e.g., 28% reported AIDS as a problem for OAs), though only 17% (n = 20) of those responding to condom-related questions reported “always using condoms.” These studies imply inaccuracy of sexual risk may be prevalent among OAs, which may play a role in sexual risk behaviors and lack of STI testing among this population. More data is needed to strengthen these tenuous links.

Summary and Aims

Many OAs are sexually active, engage in sexual risk behaviors, and are not tested for HIV/STIs. Inaccurate perceptions of sexual risk among OAs may contribute to this complex problem. Yet, there is a paucity of data to test the accuracy hypothesis as it applies to sex risk among OAs. Of the studies examining OA sexual risk, many samples do not represent community-dwelling OAs (e.g., local samples, clinical populations, HIV-positive, limited age range), assess only one aspect of sexual risk (e.g., condom use), and/or do not assess perceived risk for HIV or STIs in general. In an effort to further understand the relationship between actual and perceived sexual risk among OAs, this study examines: a) sexual risk behaviors, b) risk perceptions, and c) their accuracy/concordance in a sample of community-dwelling OAs aged 50 to 92. We hypothesized that OAs would report a range of sexual risk behaviors and a generally low perceived risk. However, OAs would conform to the accuracy hypothesis, showing an overall positive relationship between actual and perceived sexual risk. Further, underestimation of sexual risk would be frequent among OAs, especially those at high actual risk, given extant literature indicating low rates of STI testing and low likelihood of sexual health discussions.

Method

Recruitment and Procedures

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (AMT) was utilized for recruitment, which is an online crowdsourcing tool with a database of “workers” (participants) who complete “HITS” (tasks) from “requesters” (employers/researchers). Notably, the emergence of AMT as a legitimate and valid source of data collection has been supported in research (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Crump, McDonnell, & Gureckis, 2013; Mason & Suri, 2011) and successfully used to collect OA sexuality data (Graf & Patrick, 2014; Rolison, Hanoch, Wood, & Liu, 2013). Further, AMT has been found to reach samples that are more diverse and representative than other types of convenience samples (Berinsky et al., 2012; Crump et al., 2013; Mason & Suri, 2011).

To increase the reliability of data, quality assurance mechanisms were utilized both within AMT (e.g., only US participants, only one participation per IP address) and within the survey (e.g., reported birthdate, match in reported completion codes). Upon completion, participants were reimbursed $1.00, which was the typical reimbursement rate for questionnaires averaging 20–25 minutes for completion (Buhrmeister, Kwang, & Gosling 2011).

Measures

Data for the current research was collected as part of a larger study examining sexual wellness, attitudes, and experiences across adulthood (ages 18–92). The questionnaire posed 160 questions, including demographics, sexual behaviors (i.e., vaginal, oral, anal sex), sexual risk, STI testing and diagnosis, and perceived sexual risk.

Sexual risk behaviors

Seven items derived from the Sexual Risk Survey (Turchik & Garske, 2008), a valid and reliable tool, were used to measure risk. Items included: number of sexual partners the past 6 months; frequency (in the past 6 months) of vaginal, oral, and anal sex without a condom; hookup (casual) sex; sex with a new sexual partner without getting a sexual history; and sex with a new, previously sexual partner without him/her having an HIV/STI test. The use of seven items served to broaden the typical one-item sexual risk assessment (i.e., any condom use). Responses were reported as frequency of each behavior, which were utilized in descriptive and correlational analyses as well as to create high, moderate, and low sexual risk categories (see below). To further describe engagement in sexual risk behaviors, responses to each item were also dichotomized to “yes” (1) or “no” (0), except number of sexual partners—coded “none” (0), one (1), or two or more (2).

STI diagnosis and testing

Rates of lifetime STI testing and STI diagnosis were measured using one item each. Responses were reported as either “yes”, “no”, or “I don’t know”, and frequencies were calculated.

Perceived sexual risk

One item, “How susceptible do you feel you are to contracting an STI?” was used to measure perceived risk with responses on a 6-point Likert scale (1-“not susceptible” to 6-“very susceptible”).

Accuracy of risk perceptions

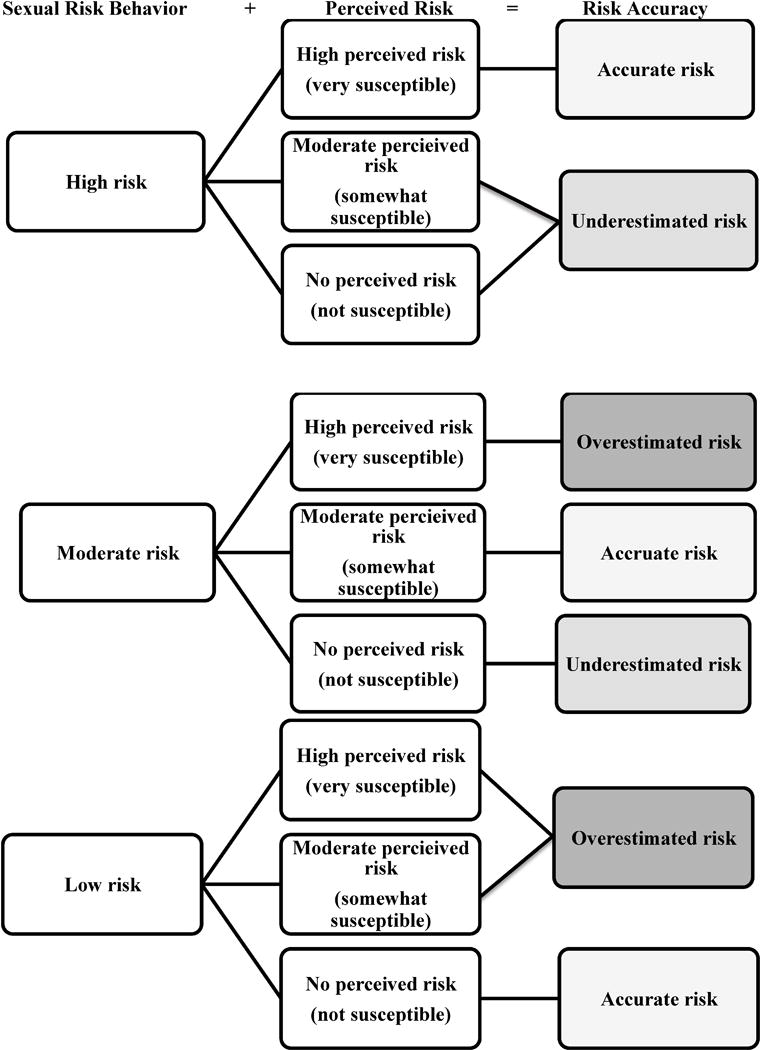

Based on previous research (Kershaw et al., 2003), participants were divided according to aggregate a) sexual risk and b) perceived risk groups, which resulted in corresponding accuracy categories (see Figure 1). The three-level sexual risk behavior groups were created based on stratifying frequencies of sexual risk behaviors by three equal percentages (i.e. tertiles), resulting in high (15+ behaviors), moderate (2–14 behaviors), and low (0–1 behaviors) groups. The three-level, ordinal perceived risk groups were created based on grouping Likert responses to the perceived risk item—very susceptible (5–6), somewhat susceptible (2–4), and not susceptible (1). Concordance of these groups resulted in three sexual risk accuracy categories: accurate, underestimated, and overestimated risk.

Figure 1.

A model of sexual risk accuracy. This figure represents potential in/accuracy categories when comparing perceived and actual sexual risk among older adults. Sexual risk behavior groups were created based on stratifying frequencies of sexual risk behaviors by three equal percentages (i.e. tertiles), resulting in high (15+ behaviors), moderate (2–14 behaviors), and low (0–1 behaviors) groups. Perceived risk groups were created based on grouping Likert responses to the perceived risk item—very susceptible (5–6), somewhat susceptible (2–4), and not susceptible (1). Based on similar groupings from Kershaw et al., 2013.

Participant Characteristics

A total of 405 participants, aged 50 to 92 (M = 60.4, SD = 5.97; 46.4% male, 53.6% female) participated. Table 1 provides descriptive data for the sample.

Table 1.

Background Data by Sexual Risk Categoriesa (N=405)

| Total Sample | Low Risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender (X2 = 24.85)** | ||||||||

| Man | 188 | 46.4 | 46 | 30.5 | 70 | 57.4 | 72 | 54.5 |

| Woman | 217 | 53.6 | 105 | 69.5 | 52 | 42.6 | 60 | 45.5 |

| Age (X2 = 11.56)* | ||||||||

| 50–59 | 191 | 51.8 | 72 | 49.7 | 54 | 49.5 | 65 | 56.5 |

| 60–69 | 150 | 40.7 | 54 | 37.2 | 50 | 45.9 | 46 | 40 |

| 70+ | 28 | 7.6 | 19 | 13.1 | 5 | 4.6 | 4 | 3.5 |

| Race (X2 = 12.61) | ||||||||

| White | 327 | 80.7 | 130 | 86.1 | 92 | 75.4 | 105 | 79.6 |

| Black | 33 | 8.2 | 13 | 8.6 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 6.8 |

| Asian | 15 | 3.7 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 5.7 | 5 | 3.8 |

| NH-PI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AI-AN | 10 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Multiracial | 20 | 4.9 | 5 | 3.3 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 6.8 |

| Marital status (X2 = 72.91)** | ||||||||

| Married | 205 | 50.6 | 43 | 31.8 | 69 | 56.6 | 88 | 66.7 |

| Divorced/separated | 93 | 23 | 53 | 35.1 | 24 | 19.7 | 16 | 12.1 |

| Sign. other – not married | 38 | 9.4 | 5 | 3.3 | 12 | 9.8 | 21 | 15.9 |

| Single | 69 | 17 | 45 | 29.8 | 17 | 13.9 | 7 | 5.3 |

| Level of education (X2 = 9.09) | ||||||||

| High school or equivalent | 42 | 10.4 | 17 | 11.3 | 10 | 8.2 | 15 | 11.4 |

| Associate’s | 39 | 9.6 | 16 | 10.6 | 13 | 10.7 | 10 | 7.6 |

| Some college | 101 | 24.9 | 42 | 27.8 | 29 | 23.8 | 30 | 22.7 |

| Bachelor’s | 149 | 36.8 | 49 | 32.5 | 49 | 40.2 | 149 | 36.8 |

| Master’s | 52 | 12.8 | 15 | 9.9 | 18 | 14.8 | 19 | 14.4 |

| Doctorate or professional | 22 | 5.4 | 12 | 7.9 | 3 | 2.5 | 7 | 5.3 |

| Sexual orientation (X2 = 3.08) | ||||||||

| Heterosexual | 380 | 93.8 | 143 | 94.7 | 116 | 95 | 121 | 91.7 |

| Homosexual | 10 | 2.5 | 4 | 2.65 | 3 | 2.5 | 3 | 2.3 |

| Bisexual | 15 | 3.7 | 4 | 2.65 | 3 | 2.5 | 8 | 6 |

| Income (X2 = 35.88)** | ||||||||

| Less than $20,000 | 68 | 17 | 37 | 25 | 19 | 15.7 | 12 | 9.2 |

| $20,000 to $30,000 | 68 | 17 | 37 | 25 | 13 | 19.1 | 18 | 13.7 |

| $31,000 to $40,000 | 50 | 12.5 | 19 | 12.8 | 17 | 14 | 14 | 10.7 |

| $41,000 to $60,000 | 82 | 20.5 | 25 | 16.9 | 29 | 24 | 28 | 21.4 |

| $61,000 to $80,000 | 61 | 15.3 | 13 | 8.8 | 22 | 18.2 | 26 | 19.8 |

| $81,000 to $100,000 | 39 | 9.8 | 9 | 6.1 | 12 | 9.9 | 18 | 13.7 |

| Over $100,000 | 32 | 8 | 8 | 5.4 | 9 | 7.4 | 15 | 11.5 |

| Sexual behaviorsb | ||||||||

| Intercourse (X2 = 205.26)** | ||||||||

| None | 166 | 41.1 | 128 | 85.3 | 32 | 26.2 | 6 | 4.5 |

| Any | 238 | 58.9 | 22 | 14.7 | 90 | 73.8 | 126 | 95.5 |

| Oral (X2 = 177.25)** | ||||||||

| None | 222 | 54.8 | 144 | 95.4 | 54 | 44.3 | 24 | 18.2 |

| Any | 183 | 45.2 | 7 | 4.6 | 68 | 55.7 | 108 | 81.8 |

| Anal (X2 = 34.72)** | ||||||||

| None | 342 | 85.3 | 146 | 98.6 | 97 | 80.2 | 99 | 75 |

| Any | 59 | 14.7 | 2 | 1.4 | 24 | 19.8 | 33 | 25 |

Sexual risk behavior groups were created based on stratifying frequencies of sexual risk behaviors by three equal percentages (i.e. tertiles), resulting in high (15+ behaviors), moderate (2–14 behaviors), and low (0–1 behaviors) groups.

Sexual behaviors were number of reported behaviors in the past 6 months and categorized as any or none.

Chi-square comparisons significant at p < .05.

Chi-square comparisons significant at p < .001.

Within the sample, 80.7% of participants identified as White, 8.2% as Black or African American, 3.7% as Asian, 2.5% as American Indian or Alaskan Native and, 4.9% as more than one race. For marital status, 50.6% were married, 23% divorced/separated, 17% single, and 9.4% had a significant other, not married. The majority of the sample had attended some college (24.9%) or attained an associate’s (9.6%), Bachelor’s (36.8%), master’s (12.8%), or doctorate or professional degree (5.4%). Only 10.4% of the sample had a high school or equivalent education. Regarding sexual orientation, the vast majority of the sample reported being primarily heterosexual (93.9%) and 6.1% reported being primarily gay, lesbian, or bisexual.

Sample representativeness

In order to characterize the current sample, it was compared to the (US) Census (2012) older-age population data. Overall, the study sample is representative of the older US population with comparable rates of gender in those 55+ (53.6% female vs. 54% Census; 46.4% male vs. 46% Census), and rates of race in those who are 50+ (White: 80.7% vs. 84.5% Census; Black/African American 7% vs. 10% Census; Asian American: 7% vs. 3.8% Census; American Indian-Alaska Native: 2.1% vs. 0.7% Census; Native Hawaiian-Pacific Islander 0% vs. 0.1%). The sample was somewhat younger than the 50+, community-dwelling US population (51.8% 50–59 vs. 42% Census; 40.7% 60–69 vs. 30.5% Census; 7.6% 70+ vs. 27.4% Census). For marital status, when categories overlap with the Census they suggest similar rates of single or widowed individuals (17% vs. 20.8% Census), with fewer married (50.6% vs. 63% Census) and more divorced or separated (23% vs. 16.2%) individuals.

The sample was notably more highly educated, with more 50+ aged individuals with a Bachelor’s degree (36.8% vs. 16.8% Census) and advanced degrees (17.2% vs. 11.3% Census), and fewer with a high school diploma or equivalent (10.4% vs. 33.2% Census), though the same percent reporting some college in both samples (24.9). This is partially due to the lack of oldest olds in this sample as compared to the Census, as that cohort tends to be less educated in general (Census, 2012).

In this sample, more OAs reported engaging in intercourse (58.9%) than oral sex (45.2%) in the past 6 months, and much less frequently endorsed anal sex (14.7%). Of note, more men than women reported engaging in intercourse (55% vs. 45% women), oral sex (59.5% vs. 33.2% women) and anal sex (25.4% vs. 5.5% women). Notably, incidence rates of sexual intercourse are comparable to studies with a large, national OA sample (53.6% older men, 42% older women; Schick et al., 2010).

Data Analysis

An outlier analysis was completed on total sexual risk behaviors reported, with 8 cases excluded in the final data set due to outlier status. Descriptive statistics were completed for background, sexual behavior, and risk variables along with bivariate analyses using Chi-square tests (see Tables 1, 2 and 3). Analyses were conducted with SPSS 21.0.

Table 2.

Sexual Risk Data by Sexual Risk Categoriesa (N=405)

| Total Sample | Low Risk | Moderate Risk | High Risk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex risk behaviorsb | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Partner number (X2 = 265.36)** | ||||||||

| None | 112 | 27.7 | 112 | 74.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| One | 241 | 59.5 | 39 | 25.8 | 96 | 78.7 | 106 | 80.3 |

| Two or more | 52 | 12.8 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 23.7 | 26 | 19.7 |

| Vaginal no condom (X2 = 201.37)** | ||||||||

| None | 228 | 56.3 | 151 | 100 | 52 | 42.6 | 25 | 18.9 |

| Any | 177 | 43.7 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 57.4 | 107 | 81.1 |

| Oral no condom (X2 = 245.66)** | ||||||||

| None | 205 | 50.6 | 151 | 100 | 39 | 32 | 15 | 11.4 |

| Any | 200 | 49.4 | 0 | 0 | 83 | 68 | 117 | 88.6 |

| Anal no condom (X2 = 39.35)** | ||||||||

| None | 360 | 88.9 | 151 | 100 | 108 | 88.5 | 101 | 76.5 |

| Any | 45 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 11.5 | 31 | 23.5 |

| Hookup sex (X2 = 22.08)** | ||||||||

| None | 372 | 91.9 | 151 | 100 | 108 | 88.5 | 113 | 85.6 |

| Any | 33 | 8.1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 11.5 | 19 | 14.4 |

| No sex hx discussion (X2 = 23.33)** | ||||||||

| None | 374 | 92.3 | 151 | 100 | 111 | 91 | 112 | 84.8 |

| Any | 31 | 7.7 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 20 | 15.2 |

| No HIV/STI test for new, previously active sex partner (X2 = 37.62)** | ||||||||

| None | 351 | 86.7 | 151 | 100 | 94 | 77 | 106 | 80.3 |

| Any | 54 | 13.3 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 23 | 26 | 19.7 |

| STIs | ||||||||

| STI tested ever (X2 = 12.35)* | ||||||||

| Yes | 181 | 45 | 57 | 38 | 60 | 50 | 64 | 48.5 |

| No | 200 | 49.8 | 80 | 53.3 | 53 | 44.2 | 67 | 50.8 |

| I don’t know | 21 | 5.2 | 13 | 8.7 | 7 | 5.8 | 1 | 0.7 |

| STI diagnosis ever (X2 = 1.72) | ||||||||

| Yes | 53 | 13.2 | 22 | 14.7 | 13 | 10.7 | 18 | 13.6 |

| No | 344 | 85.3 | 125 | 83.3 | 106 | 87.6 | 113 | 85.6 |

| I don’t know | 6 | 1.5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.8 |

| STI perceived susceptibilityb(X2 = 5.28) | ||||||||

| Not susceptible | 264 | 65.5 | 106 | 70.7 | 72 | 59 | 86 | 65.6 |

| Somewhat susceptible | 117 | 29 | 37 | 24.7 | 44 | 36.1 | 36 | 27.5 |

| Very susceptible | 22 | 5.5 | 7 | 4.6 | 6 | 4.9 | 9 | 6.9 |

Sexual risk behavior groups were created based on stratifying frequencies of sexual risk behaviors by three equal percentages (i.e. tertiles), resulting in high (15+ behaviors), moderate (2–14 behaviors), and low (0–1 behaviors) groups.

Sexual risk behaviors were number of reported behaviors in the past 6 months and categorized as any or none.

Perceived susceptibility groups were derived from original 6-point Likert scale

Chi-square comparisons significant at p < .05.

Chi-square comparisons significant at p < .001.

Table 3.

Sexual Risk Behaviors by Gender (N=405)

| Total Sample | OA Men | OA Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Partner number (X2 = 33.99)** | ||||||

| None | 113 | 27.6 | 33 | 17.4 | 80 | 36.4 |

| One | 244 | 59.5 | 116 | 61.1 | 128 | 58.2 |

| Multiple | 53 | 12.9 | 41 | 21.5 | 12 | 5.4 |

| Vaginal no condom (X2 = 3.301) | ||||||

| None | 229 | 56.1 | 97 | 51.3 | 132 | 60.3 |

| Any | 179 | 43.9 | 92 | 48.7 | 87 | 39.7 |

| Oral no condom (X2 = 34.06)** | ||||||

| None | 206 | 50.2 | 66 | 34.7 | 140 | 63.6 |

| Any | 204 | 49.8 | 124 | 65.3 | 80 | 36.4 |

| Anal no condom (X2 = 11.24)** | ||||||

| None | 364 | 88.8 | 158 | 83.2 | 206 | 88.5 |

| Any | 46 | 11.2 | 32 | 16.8 | 14 | 11.2 |

| Hookup sex (X2 = 19.34)** | ||||||

| None | 376 | 91.7 | 162 | 85.3 | 214 | 97.3 |

| Any | 34 | 8.3 | 28 | 14.7 | 6 | 2.7 |

| No sex hx discussion - new sex partner (X2 = 16.79)** | ||||||

| None | 376 | 92.2 | 164 | 86.3 | 212 | 97.2 |

| Any | 32 | 7.8 | 26 | 13.7 | 6 | 2.8 |

| No HIV/STI test for new, previously active sex partner (X2 = 37.62)** | ||||||

| None | 355 | 86.8 | 155 | 82 | 200 | 90.9 |

| Any | 54 | 13.2 | 34 | 18 | 20 | 9.1 |

Chi-square comparisons significant at p < .05.

Chi-square comparisons significant at p < .001.

Results

Sexual Risk Behavior

The median number of sexual risk behaviors within the past 6-months reported by OAs was 6 (M = 24.41, SD = 52.28); 27.7% of the sample reported “none”. Gender differences were found for each of the sex risk behaviors, with OA men reporting higher rates, except vaginal sex without a condom (see Table 3).

For condom use in the past 6 months 43.7% of OAs in the sample reported engaging in vaginal intercourse without a condom, 49.4% of the sample reported oral sex without a condom, and 11.1% reported anal sex without a condom. Remaining sexual risk behaviors for the sample were as follows: sex with a new partner without a sexual history discussion (7.7%), hookup sex (8.1%), having sex with two or more partners (12.8%), and having sex with a new, previously active sexual partner who has not had an STI test (13.3%). Rates were significantly different by risk category for all sex risk behaviors, following the trend of increasing numbers of OAs reporting each behavior at increased risk level (see Table 2).

STIs

Forty-five percent of the sample indicated they had ever been tested for an STI, with comparable rates by gender (men = 52.2%; women = 47.8%). Lifetime testing did significantly vary by current sex risk level, with higher rates in higher risk (see Table 2). Notably, 13.2% of OAs in the sample reported ever getting an STI diagnosis, with 16.1% of those being older women and 9.5% being older men. The majority of OAs (65.5%) perceived that they were not susceptible to contracting an STI; 29% perceived they were somewhat susceptible; 5.5% perceived they were very susceptible. The average perceived risk score (1 to 6 scale) was 1.64 (SD = 1.15). More older men reported being somewhat (34% vs. 24.8% women) to very (6.8% vs 4.1% women) susceptible to an STI, and more older women reported that they were not susceptible (37.9% vs. 27.6% men) (X2(2) = 6.57, p = .04). In contrast to sexual risk behaviors, STI testing and perceived susceptibility were not significantly different by sexual risk category, suggesting that these variables were relatively stable across risk level (see Table 2).

Accuracy of Risk Perceptions

Accuracy of sexual risk was first examined by analyzing the relationship between raw scores for total reported sexual risk behaviors in the past 6 months and perceived susceptibility to STIs. Contrary to expectations, there was no significant relationship between total risk behaviors and perceived risk scores in this sample (r = .04, p=.46).

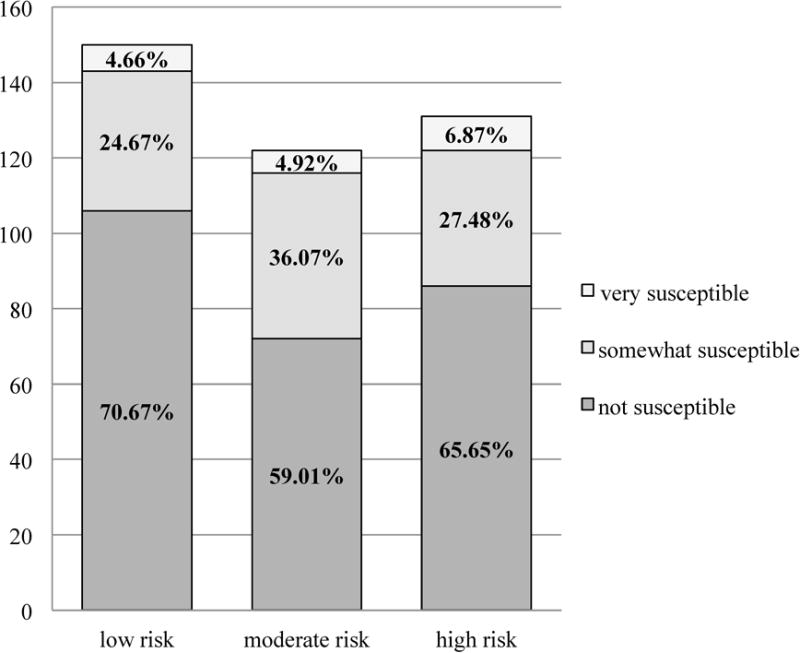

Accuracy of sexual risk perceptions was also examined by calculating the concordance between levels of actual and perceived sexual risk (see Figure 1). The aggregate measures of sexual risk showed that 36.7% of the sample was categorized as low risk, 29.7% of the sample was categorized as having moderate risk, and 32.1% categorized as high risk. In comparison, 65.5% of the sample perceived themselves as not susceptible to STIs, 29.1% as somewhat susceptible, and only 5.4% as very susceptible. Thus, despite an increase in the level of sexual risk, there was a lack of corresponding increase in the perceived risk level (i.e., susceptibility) (see Figure 2). A Chi-square comparison was conducted to test the in/dependence of levels of risk and perceived risk. The results were nonsignificant (X2(4) = 5.28, p = .26).

Figure 2.

Level of sexual risk behavior by level of perceived risk. This figure illustrates the concordance of risk and perceived risk, or the accuracy of risk perceptions of the sample.

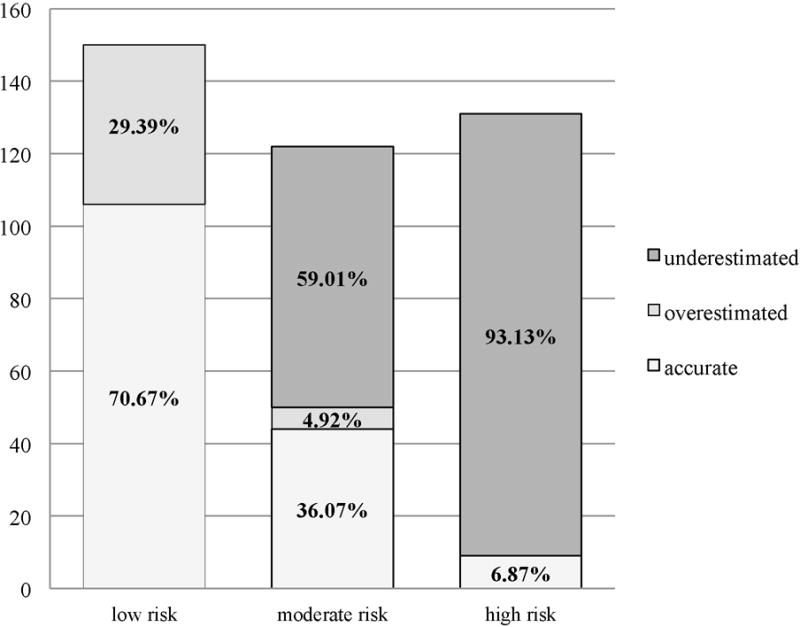

Accuracy categories were determined by the fit between actual sexual risk (low, moderate, or high risk) and perceived sexual risk (not, somewhat, or very susceptible), based on previous sexual risk literature (Kershaw et al., 2003) (see Figure 1). Overall, 48.9% (n = 194) of the sample underestimated their risk level, 12.4% (n = 50) overestimated their risk level, and 39.5% (n = 159) had accurate risk perceptions. These accuracy categories were further broken down by sexual risk level and showed the following: high sex risk underestimaters were most prevalent (30.3%, n = 122), low risk accurates were next (26.1%, n = 105), then moderate risk underestimaters (18.4%, n = 74), then moderate risk accurates and low risk overestimators (both at 11.2%, n = 45), and high risk accurates (2.2%, n = 9) and moderate risk overestimators (0.7%, n = 3) were the least prevalent types. To further illustrate these connections, a depiction of sex risk level (low, moderate, high) by accuracy of perceived risk (underestimated, overestimated, accurate) was examined and is presented in Figure 3. The results show that as sexual risk level increased, the proportion of those who accurately perceived their sexual risk decreased (X2(4) = 259.34, p < .001).

Figure 3.

Accuracy of perceived sexual risk by actual sex risk category

Discussion

This study compared actual and perceived sexual risk among a community-dwelling sample of OAs across the US (ages 50 to 92), to provide much needed information about the accuracy of these perceptions. In contrast to previous literature with more narrowly defined sexual risk (Schick et al., 2010; Glaude-Hosch et al., 2015), this study assessed multiple sexual risk behaviors across a variety of relationship statuses and sexual activity levels. Consistent with expectations and previous studies, sexual risk—at some level—is prevalent, with 72.3% of the sample reporting at least one sexual risk behavior in the past 6 months and approximately two-thirds of the sample reporting multiple sexual risk behaviors. Lack of condom use in the sample for vaginal (49%) or oral sex (43%) was most prevalent. Comparison is difficult, as sample and measurement strategies differ across studies; however, the message remains consistent: OA condom use is infrequent (Gaude-Hosche et al., 2015; Schick et al., 2010). Perhaps more compelling is the prevalence of sexual risk behaviors (8–13% reporting at least once in the last 6 months) rarely examined among OAs (anal sex without a condom, having sex with more than one partner, sex with potentially risky partners, hooking up). Although less prevalent than vaginal or oral sex without a condom, the findings remain concerning as they add a needed dimension to a complex picture of OA sexual risk that warrants attention.

There were notable differences in reported sexual risk across gender. Previous studies on community samples often show comparable sexual risk across gender, predominantly measured as condom use in intercourse (Fisher, 2010; Schick et al., 2010). However, in this sample, a multidimensional assessment of risk was used (i.e., frequency, multiple risk behaviors) and OA men reported significantly more sexual risk behavior than OA women. OA men and women were comparable in condom use for vaginal sex (as in previous studies), but OA men reported significantly higher rates on every other sexual risk behavior. This implies the need for a multidimensional assessment of risk, and gives providers integral information about gender differences in sexual risk among their OA patients.

Low rates of STI testing were found among OAs in this sample—45% ever having an STI test. This is comparable to other lifetime testing rates (Sormanti & Shibusawa, 2007) but somewhat lower than Schick et al. (2010) (60.6% of men, 71.6% of women), though their sample examined only sexually active OAs with new or multiple partners. Rates of lifetime STI testing in this sample appear to differ by current sexual risk level, with the largest increase in testing between low (38%) and moderate (50%) risk. Prevalence of sexual risk and low rates of lifetime STI testing in this sample is concerning, and likely partially due to the low perception of sexual risk, with two thirds reporting they were not susceptible to STIs. Low reported perceived risk is consistent with the literature (Glaude-Hosche et al., 2015; Jackson et al., 2005; Ward et al., 2011). More OA men in the sample perceive themselves as somewhat (34%) to very risky (6.8%), compared to OA women (24.8%, 4.1%), which is consistent with gender differences in risky behaviors in this sample.

A unique contribution of this study is the ability to demonstrate in/accuracy of OAs sexual risk estimations. Health behavior theories and research suggest that accuracy of perceived risk is essential and linked to health behavior motivation and change, including sexual risk behaviors (Brewer et al., 2004; Kershaw et al., 2003; Orel et al. 2005). Based on the accuracy hypothesis and previous studies on risk estimation (Brewer et al., 2004; Kershaw et al., 2003), it was expected that actual and perceived sexual risk would have, at least, a slight, positive relationship in this OA sample. This was not supported; no significant relationship was found (r = .04). Similarly, Chi-square analyses of risk and perceived risk implied that these variables were independent in this sample. In contrast, the comparison study of female adolescents (Kershaw et al., 2003) found a moderate positive relationship between perceived and actual risk (r = .32), even though a large proportion of their sample was considered inaccurate (51%). Only 39.5% of this OA sample reported accurate risk estimations and approximately half of OAs underestimated their sexual risk (48.1%). Taken together, the findings suggest that regardless of risk escalation, there is no corresponding rise in perceived risk among OAs, as opposed to findings in adults (Holzman et al., 2001) and female adolescents (Kershaw et al., 2003). Without accurate risk estimates, OAs are unlikely to develop motivation to change their behaviors and/or get tested, as seen in other health behavior processes (Brewer et al., 2004). Perhaps more striking is the proportion of inaccurate risk estimates among the sexual risk categories. Underestimation expands significantly as risk increases, with 93.1% of OAs in the high sexual risk category underestimating their risk. The majority of OAs who were moderately risky also underestimated their risk (59%).

There are likely several factors contributing to this inaccuracy, including lack of STI education, lack of sexual health discussions, and ageist/paternalistic views that permeate our understanding of a/sexuality in later life. Psychological maintenance theory also provides an explanation, which indicates that OAs may underestimate their sexual risk due the psychological threat of acknowledging destructive behavior (i.e. sexual risk) and the possible consequences (i.e., STI/HIV) (Bauman & Siegel, 1987). Further, in accordance with the theory, as sexual risk increases, psychological threat increases, and the need to maintain psychological health increases, which necessitates strategies such as avoidant coping (i.e., lack of testing). Thus, to support reduced sexual risk and STI testing among OAs, providers need to address the potential psychological threat and educate OAs (e.g., reduction of stigma, increase age-specific STI knowledge) and help build active coping strategies (e.g., condom negotiation skills).

The findings are poignant in light of the national STI testing and counseling recommendations, or lack thereof, for those 64+ (Brooks et al., 2012). If providers are opting out of screening/testing at age 64, then what is the impetus to recommend testing? The guidelines suggest that risk assessment will help determine if testing and behavioral counseling should be conducted. However, research has shown that sexual discussions rarely occur with OAs in healthcare settings (Gott, Hinchliff, & Galena, 2004; Loeb, Lee, Binswanger, Ellison, & Aagaard, 2011; Ports et al., 2014). Providers need to be aware of the risk potential among OAs and be equipped to determine sexual health needs.

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations should be considered when interpreting and evaluating the results. This was a cross-sectional study, utilizing a convenience sample of the general OA population that was recruited via an online crowdsourcing tool (AMT). Although samples from this source have been found to be comparable to other convenience samples and larger probability samples across several demographic categories (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Berinsky et al., 2012), this non-probability sample has limited generalizability as it is more educated than the general population and limits understanding of in/accuracy of sex risk in less educated samples. A potential limit to generalizability is that oldest olds were underrepresented in the sample (Syme & Cohn, 2015), which may be partially due to lower digital literacy among oldest olds. The use of AMT may have limited this sample to more digitally literate OAs; however, Zickuhr and Madden (2012) reported that 53% of adults 65 and older in the United States used the internet or email, and 70% of those individuals 65 and older accessed the internet or email on a daily basis. In order to address digital literacy, future studies may focus on sampling through multiple sampling techniques (e.g., online, phone). Though this sample may be limited in some areas, AMT remains a valid source to recruit samples that are difficult to reach, including OAs, and replication across samples will strengthen these findings.

There are also potential limitations to the measurement of sexual risk. First, sexual risk level was determined relative to the sample—as opposed to benchmarked—which could represent high, moderate, and low risk in comparable samples of community-dwelling OA. For number of sexual partners, OAs reporting more than one partner were collapsed into one category, potentially limiting variability in that group. However, the average number of partners for the sample was 1.2 with low variability (SD = 2.19). Of those OAs with more than one partner (n = 53, 12.8%) the majority reported two partners (n = 29, 7.1%), with few dispersed across higher number of partners (n = 24, 5.7%). Also, risk behaviors were considered within and outside partnered relationships that may or may not be monogamous. Thus, a risk behavior includes married individuals reporting vaginal intercourse without a condom, signifying increased susceptibility to STIs. Some studies have focused on unpartnered OAs (Schick et al. 2010); however, it is critical to understand that sexual behaviors within a partnered relationship are not, by definition, free of risk. Research has shown that 20–25% of men and 10–15% of women across adulthood have engaged in extramarital affairs (Munsch, 2012). Further, a significant proportion of OA women (82%) and men (23%) contract HIV through heterosexual contact (Pilowsky & Wu, 2015). Combined with the fact that lifetime and incident STI testing rates among OAs are very low, unknown sexual partner STI status may be very high among both partnered and unpartnered OAs. Additionally, it was decided to include both recently sexually active and inactive OAs in the sample, thus incorporating OAs who are not sexually active into the low sexual risk group. Though they are not currently sexually active, this OA group may also misjudge their sexual risk, which is represented in the overestimation category.

Conclusions and Implications

Older adults are engaging in sexual risk behaviors, and a concerning number are underestimating their risk and not getting STI testing. Further, OAs are not having sexual health discussions with their providers (Ports et al., 2014). These factors contribute to increasing rates of STIs reported in the US, which is notable in light of the national STI testing recommendations (Brooks et al., 2012). Providers opt-out of universal testing for those 64+, unless sexual risk assessment determines testing is warranted. Hence, providers need to be aware of the risk potential among OAs and be equipped to determine sexual health needs. Researchers have identified specific barriers to conducting sexual health discussions for both providers and OAs (e.g., embarrassment, lack of knowledge; Gott et al., 2004), and further intervention research focusing on addressing those barriers is warranted.

Additionally, behavioral health providers in multi- and inter-disciplinary settings are uniquely positioned to provide education and training to primary care providers and healthcare teams to increase the likelihood that sexual health discussions occur with OA patients so that STIs are prevented and/or treated. Education can be provided to healthcare teams aimed at increasing awareness of OA sexual risk. Skills can be taught to providers to facilitate sexual health discussions, using sexual history taking models such as the PLISSIT (Mettner, 2013; Taylor & Davis, 2006) or the 5 P’s model (California Department of Public Health, 2011). Information on OA STI and HIV can be made visible within clinical settings and provided to our own patients, which are available from organizations such as AARP (2013), CDC (2015), and the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America (ACRIA, n.d) (e.g., Age is Not a Condom campaign). It is also important to raise awareness of available resources for screening and treatment with OA patients. For instance, Medicare (Part B) reimburses for yearly STI (including HIV) screenings and behavioral counseling for adults at risk (Medicare.gov, n.d.). These actions would illustrate a prioritization of sexual health for OAs and facilitate prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the following research assistants for their contributions: Dallas Lopez, Erwin Caalaman, Elizabeth Cottrel, and Anna Mitarotondo.

Contributor Information

Maggie L. Syme, Center on Aging; Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, 66502; USA

Tracy J. Cohn, Department of Psychology; Radford University, Radford, VA, 24142; USA

Jessica Barnack-Tavlaris, Department of Psychology; The College of New Jersey, Ewing Township, NJ 08628; USA.

References

- AIDS Community Research Initiative of America. Age is not a condom. n.d. Retrieved from: http://ageisnotacondom.org/EN/?page_id=86/

- Akers A, Bernstein L, Henderson S, Doyle J, Corbie-Smith G. Factors associated with lack of interest in HIV testing in older at-risk women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(6):842–858. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Retired Persons. Should you worry about sexually transmitted infections? 2013 Retrieved from: http://www.aarp.org/home-family/sex-intimacy/info-03-2013/sexually-transmitted-infections-should-you-worry.html.

- Bauman LJ, Siegel K. Misperception among gay men of the risk for AIDS associated with their sexual behavior. Journal Of Applied Social Psychology. 1987;17(3):329–350. [Google Scholar]

- Berinsky AJ, Huber GA, Lenz GS. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s mechanical turk. Political Analysis. 2012;20(3):351–368. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpr057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer NT, Weinstein ND, Cuite CL, Herrington JE. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27(2):125–130. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JT, Buchacz K, Gebo KA, Mermin J. HIV infection and older Americans: The public health perspective. American Journal Of Public Health. 2012;102(8):1516–1526. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling S. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives On Psychological Science. 2011;6(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Public Health. A clinician’s guide to sexual history taking. 2011 Retrieved from: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/pubsforms/Guidelines/Documents/CA-STD-Clinician-Guide-Sexual-History-Taking.pdf.

- Catania J, Kegeles S, Coates T. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: An AIDS Risk Reduction Model (ARRM) Health Education Quarterly. 1990;17(2):53. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among older Americans. 2015 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/age/olderamericans/

- Crump MC, McDonnell JV, Gureckis TM. Evaluating Amazon’s Mechanical Turk as a tool for experimental behavioral research. Plos ONE. 2013;8(3):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durvasula R. HIV/AIDS in older women: Unique challenges, unmet needs. Behavioral Medicine. 2014;40(3):85–98. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2014.893983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LL. AARP (Washington, DC) 2010. Sex, romance, and relationships: AARP survey of midlife and older adults. [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, Lee SJ, Wallace SP, Nakazono T, Newman PA, Cunningham WE. HIV testing among clients in high HIV prevalence venues: disparities between older and younger adults. AIDS care. 2015;27(2):189–197. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.963008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaude-Hosch JA, Smith ML, Heckman TG, Miles TP, Olubajo BA, Ory MG. Sexual behaviors, healthcare interactions, and HIV-related perceptions among adults age 60 years and older: An investigation by race/ethnicity. Current HIV Research. 2015;13(5):359–368. doi: 10.2174/1570162x13666150511124959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health with older people. Social science & medicine. 2004;58(11):2093–103. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman J. Knowledge and attitudes about HIV/AIDS among community-living older women: Reexamining issues of age and gender. Journal Of Women & Aging. 2007;19(3–4):53–67. doi: 10.1300/J074v19n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzman D, Bland S, Lansky A, Mack K. HIV-related behaviors and perceptions among adults in 25 states: 1997 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1882–1888. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson F, Early K, Schim SM, Penprase B. HIV knowledge, perceived seriousness and susceptibility, and risk behaviors of older African Americans. Journal of Multicultural Nursing & Health. 2005;11(1):56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BK. Sexually transmitted infections and older adults. Journal Of Gerontological Nursing. 2013;39(11):53–60. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20130918-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw TS, Ethier KA, Niccolai LM, Lewis JB, Ickovics JR. Misperceived risk among female adolescents: Social and psychological factors associated with sexual risk accuracy. Health Psychology. 2003;22(5):523–532. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. The New England Journal Of Medicine. 2007;357(8):762–775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb DF, Lee RS, Binswanger IA, Ellison MC, Aagaard EM. Patient, resident physician, and visit factors associated with documentation of sexual history in the outpatient setting. Journal of general internal medicine. 2011;26(8):887–93. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1711-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes CA, Louis M. Knowledge of AIDS, perceived risk of AIDS, and at-risk sexual behaviors among older adults. Journal Of The American Academy Of Nurse Practitioners. 2003;15(11):509–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2003.tb00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mairs K, Bullock SL. Sexual-risk behaviour and HIV testing among Canadian snowbirds who winter in Florida. Canadian Journal On Aging. 2013;32(2):145–158. doi: 10.1017/S0714980813000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Suri S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;44(1):1–23. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare.gov. Sexually transmitted infections (STI) screening and counseling. n.d. Retrieved from: https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/sexually-transmitted-infections-screening-and-counseling.html.

- Mettner J. Can we talk about sex? Seven things physicians need to know about sex and the older adult. Minnesota Medicine. 2013;96(8):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch C. The science of two-timing: The state of infidelity research. Sociology Compass. 2012;6(1):45–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00434.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orel N, Spence M, Steel J. Getting the message out to older adults: Effective HIV health education risk reduction publications. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2005;24(5):490–508. [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wu L. Sexual risk behaviors and HIV risk among Americans aged 50 years or older: a review. Substance Abuse And Rehabilitation. 2015;6:51–60. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S78808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ports KA, Barnack-Tavlaris JL, Syme ML, Perera RA, Lafata JE. Sexual health discussions with older adult patients during periodic health exams. Journal Of Sexual Medicine. 2014;11(4):901–908. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G, Mazzoni D, Zani B. Psychosocial predictors and HIV-related behaviors of old adults versus late middle-aged and younger adults. Journal Of Aging And Health. 2015;27(1):123–139. doi: 10.1177/0898264314538664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece M, Herbenick D, Schick V, Sanders S, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Condom use rates in a national probability sample of males and females ages 14 to 94 in the United States. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(Suppl 5):266–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger KS, Mignone J, Kirkland S. Social aspects of HIV/AIDS and aging: A thematic review. Canadian Journal On Aging. 2013;32(3):298–306. doi: 10.1017/S0714980813000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolison J, Hanoch Y, Wood S, Liu P. Risk-taking differences across the adult life span: A question of age and domain. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2013;69(6):870–880. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar A, Nevedal A, Neufeld S, Berry R, Luborsky M. What do we know about older adults and HIV? A review of social and behavioral literature. AIDS Care. 2011;23(10):1187–1207. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.564115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick V, Herbenick D, Reece M, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Middlestadt SE, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behaviors, condom use, and sexual health of Americans over 50: Implications for sexual health promotion for older adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(Suppl 5):315–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman CA, Harvey SM, Noell J. ‘Are they still having sex?’ STIs and unintended pregnancy among mid-life women. Journal Of Women & Aging. 2005;17(3):41–55. doi: 10.1300/J074v17n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrard J, Wainwright E. Sexually transmitted infections in older men. Maturitas. 2013;74(3):203–205. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KP, Christakis NA. Association between widowhood and risk of diagnosis with a sexually transmitted infection in older adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(11):2055–62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160119. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/215090893?accountid=10813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TK, Larson EL. HIV sexual risk behavior in older Black women: A systematic review. Women’s Health Issues. 2015;25(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sormanti M, Shibusawa T. Predictors of condom use and HIV testing among midlife and older women seeking medical services. Journal Of Aging And Health. 2007;19(4):705–719. doi: 10.1177/0898264307301173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme ML, Cohn TJ. Examining aging sexual stigma attitudes among adults by gender, age, and generational status. Aging & Mental Health. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1012044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchik JA, Garske JP. Measurement of sexual risk taking among college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(6):936–948. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9388-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward EG, Disch WB, Schensul JJ, Levy JA. Understanding low-income, minority older adult self-perceptions of HIV risk. JANAC: Journal Of The Association Of Nurses In AIDS Care. 2011;22(1):26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickuhr K, Madden M. Older adults and internet use: For the first time, half of adults ages 65 and older are online. Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. 2012 Retrieved September 28, 2015, from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Older_adults_and_internet_use.pdf.