Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of pregnancy and delivery mode on cytokine expression in the pelvic organs and serum of lysyl oxidase like-1 knockout (Loxl1 KO) mice, which develop pelvic organ prolapse (POP) after delivery.

Methods

Bladder, urethra, vagina, rectum and blood were harvested from female Loxl1 KO mice during pregnancy, after vaginal or cesarean delivery, and from sham cesarean and unmanipulated controls. Pelvic organs and blood were also harvested from pregnant and vaginally delivered wild-type (WT) mice and from unmanipulated female virgin WT controls. Specimens were assessed using qRT-PCR and/or ELISA.

Results

Both Cxcl12 and Ccl7 mRNA were significantly upregulated in the vagina, urethra, bladder, and rectum of pregnant Loxl1 KO mice compared to pregnant WT mice, suggesting systemic dysregulation of both of these cytokines in Loxl1 KO mice as a response to pregnancy. The differences in cytokine expression between Loxl1 KO and WT mice in pregnancy persisted after vaginal delivery. Ccl7 gene expression increases faster and to a greater extent in Loxl1 KO mice, translating to longer lasting increases in CCL7 in serum of Loxl1 KO mice after vaginal delivery, compared to pregnant mice.

Conclusions

Loxl1 KO mice have an increased cytokine response to pregnancy, perhaps because they are less able to reform and re-crosslink stretched elastin to accommodate pups and this resultant tissue stretches during pregnancy. Upregulation of CCL7 after delivery could provide an indicator of level of childbirth injury, to which the urethra and vagina appear to be particularly vulnerable.

Keywords: Pelvic organ prolapse, vaginal delivery, mice, LOXL-1, inflammatory cytokines

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is the descent of one or more pelvic organs into the vagina. Although not life-threatening, POP significantly reduces quality of life due to bulge symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and social embarrassment.1 The incidence of POP increases with age, peaking at 71–73 years old with an incidence of 4.3 per 1000 women, leading to a 12% lifetime risk of undergoing surgery.2

Aberrant connective tissue metabolism, genetic factors, obesity, advanced age, pregnancy and vaginal delivery are among the most important risk factors for POP.1 Maternal injuries of childbirth are believed to contribute significantly since increased length of 2nd stage of labor, large newborn weight, and multiparity increase the risk of POP.3 Previous studies have used imaging assessments of patients and mechanical models to describe the extent of anatomical injuries to the maternal pelvic floor sustained during childbirth in women.4–6 However, little research has been conducted to elucidate molecular markers for maternal injury in genitourinary tissues during the peripartum period that might provide insight into the mechanisms of injury that could lead to POP.7–9

Animal models have become invaluable for investigating the role of pregnancy and parturition in development of POP.10 Although, no animal model is capable of incorporating all the characteristics and risk factors of POP in women, lysyl oxidase like-1 knockout (Loxl1 KO) mice develop POP with phenotypic characteristics and risk factors similar to women, although they present a higher incidence of rectal prolapse than humans.11–14 LOXL1 is a metalloenzyme responsible for crosslinking tropoelastin into its functional form, elastin, which provides the extracellular matrix (ECM) with its structure and recoil properties.15 Similar to women, parity is the leading risk factor for POP in Loxl1 KO mice and POP is delayed, but not prevented, by cesarean delivery.11,12 In addition, the prolapse rate in Loxl1 KO mice increases with age, and presents with variable prolapse grades and incidences (50–80%).16,17

Previous work has demonstrated that stem cell homing cytokines become upregulated after injury in a variety of different tissues.18–23 The exact pathway for the regulation of these cytokines is still unclear. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that targeting the modulation of cytokines and their receptors at different time points after acute injury could be useful for development of novel therapeutics.18,23,24 Chemokine C-C motif ligand 7 (CCL-7), formerly known as monocyte-specific chemokine 3 (MCP-3), and chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 12 (CXCL-12), formerly known as stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) function as signaling molecules to recruit circulating progenitors and stem cells, facilitating recovery from injury.20,21,24 CCL-7 is responsible for recruiting hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells to the site of injury, where the mesenchymal stem cells induce fibroblasts to remodel ECM.20 CXCL-12 signals for hematopoietic and endothelial stem cells, contributing to angiogenesis in the area of injury.21

We have previously investigated upregulation in CCL-7 and CXCL-12 in rat pelvic organs after ischemia and in other injury models.7,9,20,21,25 Given the response of these cytokines to injury, they could be used as potential injury markers as they are mediators of inflammatory response.8,18,23 We hypothesize that pregnancy and delivery mode will differentially affect the concentration and expression of CCL-7 and CXCL-12 both in the pelvic organs and systemically in Loxl1 KO and wildtype (WT) mice. The primary aim of the present study was to determine the differential effect of pregnancy and delivery mode on CCL-7 and CXCL-12 expression in the pelvic organs and serum of Loxl1 KO and WT mice. The secondary aims were to determine changes in expression with pregnancy and pup delivery in Loxl1 KO and WT mice and assess differential expression between cesarean and vaginal delivery in LOXL1 KO mice.

Materials and Methods

Animal Breeding Techniques and Tissue Harvest

All work was performed with the approval of the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). One hundred twenty-six age-matched Loxl1 KO female mice were bred at 8–9 weeks of age. The presence of a vaginal plug was used to approximate gestational day 1. Mice were then randomized into 3 groups: vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, and pregnant. Bladder, urethra, vagina, rectum, and serum were harvested at the following time points: 15 minutes, 1, 4, 12, 24, 48 hours, or 4, 7 days after injury (vaginal delivery or cesarean-Figure 1A). These time points were selected based on the timecourse of cytokine expression in previous studies.7,9,22,25,26 Loxl1 KO mouse gestation duration is approximately 21 days, so, as a feasible time point for studying the effects of pregnancy in the absence of delivery as a control for delivered mice, tissues were harvested on the 20th day of gestation, prior to parturition for the pregnant group (Figure 1A). Sixty-four additional age-matched virgin Loxl1 KO female mice were utilized as sham cesarean injury controls or unmanipulated virgin controls (Figure 1A). These animals were not placed with male breeders but were housed under identical conditions with a breeder diet, and had organs harvested at the same time points. All procedures were performed with animals under isoflurane anesthesia.

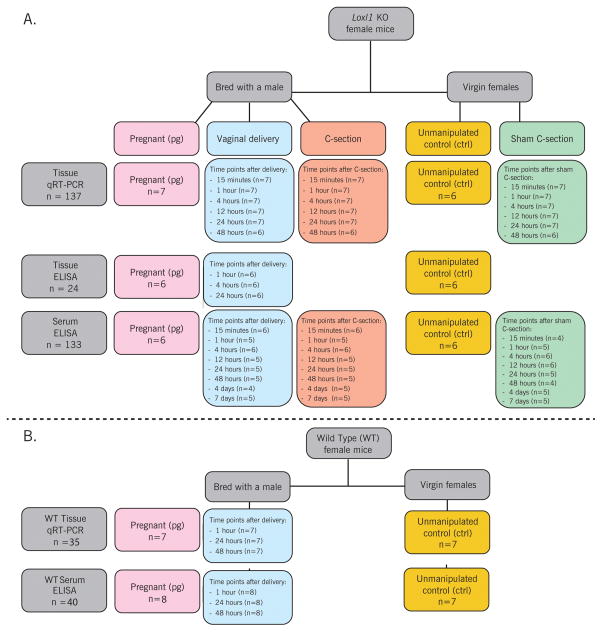

Figure 1.

Experimental design flow chart showing Loxl1 KO mice with tissues harvested for mRNA (qRT-PCR) analysis, Loxl1 KO mice with tissues harvested for protein (ELISA) analysis, and Loxl1 KO with blood harvested for protein (ELISA) analysis (A); WT mice with tissues harvested for mRNA (qRT-PCR) analysis (B) The total number of animals in these charts appears to be higher than the total number of animals in the study since blood was harvested from the same animals that had tissue harvested, but not all blood samples were viable to have serum collected.

Twenty-eight wild type (WT) female mice (Jackson Laboratory hybrid C57B1/6 and Sv129) were bred at 8 weeks old. Pelvic organs and serum were harvested on the 20th day of gestation or 1, 24, or 48 hours after vaginal delivery (Figure 1B), selected based on the data from Loxl1 KO mice as the seminal time points for comparison. One additional animal at each timepoint had serum harvested only due to problems with organ harvest. Pelvic organs and serum was also harvested from 7 additional age-matched virgin WT unmanipulated control females for comparison (Figure 1B).

Cesarean delivery of Loxl1 KO mice was performed as modified from our previous work.11 WT mice did not undergo Cesarean delivery. For Cesarean delivery, the abdomen was entered in layers under 2% isofluorane anesthesia, through a transverse incision between the 1st and 2nd pair of nipples. The uterus was exteriorized and multiple incisions were made on the anti-mesenteric side of each uterine horn. One to three pups, each with its placenta, were removed through each incision. Uterine incisions were closed with single stitches, and the abdominal incision was closed in a running fashion (6-0 silk). The vagina was not manipulated during cesarean delivery. For sham cesarean injury, both non-pregnant uterine horns were exposed and a single incision was made on each horn. Uterine and abdominal incisions were closed as described above. Postoperative subcutaneous buprenorphine (0.1mg/kg) was given to animals in cesarean and sham-cesarean groups twice a day for 48 hours.

Pelvic organs were harvested under a surgical microscope via a midline abdominal incision after which the pubic symphysis was opened for complete urethral visualization. The bladder and urethra were dissected from the anterior vaginal wall, and then the urethra was transected from the bladder. The vagina was dissected from the rectum and transected proximally at the cervix level and distally at the perineal skin. The rectum directly underlying the vagina was also harvested. Blood samples were obtained by direct cardiac aspiration, and were allowed to clot prior to being centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 15 minutes. The supernatant (serum) was aspirated and stored at −80°C. All harvested tissues were stored at −80°C until tissue digestion for RNA isolation for quantitative real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Gene Expression Analysis

Frozen tissues (n=6–7 per time point in each group; Figure 1) were ground in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was isolated using the RNAqueous®-4PCR kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY #AM1914) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop® ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Reverse transcription reactions were performed in 20 μl of reaction volume with 300 ng of total RNA, random primers, and 1 unit of reverse transcriptase at 25°C for 10 minutes, 37°C for 120 minutes and 85°C for 5 minutes (High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, #4368814, Life Technologies). Twenty-five ng of input cDNA was used in each 25 μl reaction for qRT-PCR (TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix: PN 4369016, ABI Prism 7500, Life Technologies). Mouse CCL-7 (#Mm00443113_m1) and CXCL-12 (#Mm00445552_m1) primer-probes were obtained from Life Technologies. The endogenous control was 18S (#4319413), and the standard curve method was used to determine the relative amount of the target genes.

Tissue Protein Analysis

Due to the amount of tissue needed to perform biochemical analysis, RNA isolation for qRT-PCR and ELISA were assessed in different animals (Figure 1A). Frozen tissues were crushed in liquid nitrogen. Whole tissue extracts were prepared using a solution composed of 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 150mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 1 mM disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Na2EDTA), 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland #11697498001) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) added to the frozen crushed tissues which were then homogenized. Tissue lysates were kept on ice at 4°C for 20 minutes and then centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. The concentration of total protein was estimated by Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA #500-0006) using bovine serum albumin (BSA, Life Technologies # 15561020) as a standard. One-hundred μg per sample of whole tissue extracts were tested using ELISA kits for CCL-7 and CXCL-12 (#BMS6006INST, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Serum Protein Analysis

Serum samples were thawed slowly at 4°C. Concentration of CCL-7 in serum was quantified using 25 μl of serum with duplicate wells for each sample, using the same ELISA kits as above.

Data Analysis

Gene expression data is presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for relative expression normalized to the endogenous control. SEM was utilized as it is appropriate when comparing populations, as in this study. Sample size analysis indicated that 6–8 animals/group would be sufficient to test the hypothesis at multiple time points. The data was analyzed using mixed model regression. After the mixed models analysis, posthoc comparisons were made using Dunnett’s, Bonferroni, or Students’ t-test to identify significant differences between individual groups as appropriate since multiple post-hoc tests for mean difference significance testing were needed to address different aspects of the analysis. Dunnett’s post hoc test was used to compare delivery type outcomes (after vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, or sham cesarean injury) within Loxl1 KO and WT strains to pregnant animals. The Bonferroni post hoc test was used to assess specific contrasts between delivery types across time. The Students’ t-test was used to compare Loxl1 KO versus WT outcomes at the same time point. P < 0.05 was used in all cases to indicate a statistically significant difference between groups. Since there are many comparisons in this study, for clarity we only report if the difference was statistically significant with P < 0.05 or not.

Results

Differential expression of Cxcl12 and Ccl7 between WT and KO mice

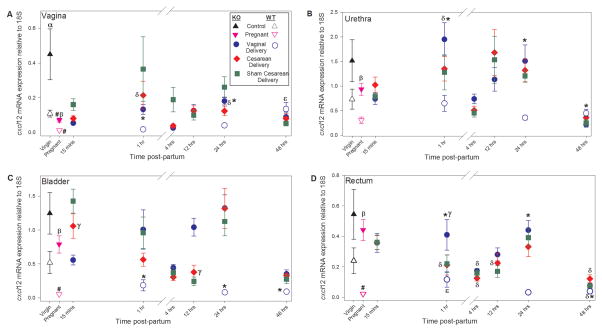

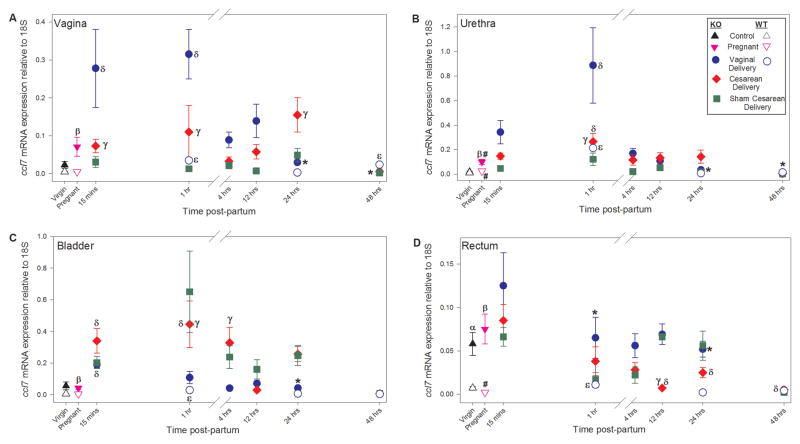

Compared to virgin WT mice, Cxcl12 mRNA was significantly upregulated in the vagina of virgin Loxl1 KO mice but not in the urethra, bladder, or rectum (Figure 2). Ccl7 mRNA, on the other hand, was significantly upregulated in the rectum of virgin Loxl1 KO mice, but not in the vagina, urethra, or bladder (Figure 3). Both Cxcl12 and Ccl7 mRNA were significantly upregulated in the vagina, urethra, bladder, and rectum of pregnant Loxl1 KO mice compared to pregnant WT mice.

Figure 2.

Relative Cxcl12 gene expression normalized to expression of 18S in the vagina (A), urethra (B), bladder (C), and rectum (D) of Loxl1 KO and WT mice at different time points after vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, sham cesarean injury, and in pregnant and unmanipulated virgin mice. α indicates a significant difference between unmanipulated virgin Loxl1 KO and WT mice; β indicates a significant difference between pregnant Loxl1 KO and WT mice; # indicates a significant difference between pregnant and virgin mice of the same genotype; * indicates a significant difference between Loxl1 KO and WT vaginal delivered mice at the same postpartum time point; δ indicates a significant difference between vaginal or cesarean delivered and pregnant Loxl1 KO mice; ε indicates a significant difference between vaginal delivered and pregnant WT mice; γ indicates a significant difference between vaginal delivered and cesarean delivered Loxl1 KO mice at the same postpartum time point. In all cases, p < 0.05 was used to indicate a statistically significant difference. Each symbol represents the mean ± standard error of the mean of data from 6–7 mice. Note that the y-axis scales are different for each panel since comparisons between organs were not made.

Figure 3.

Relative Ccl7 gene expression normalized to expression of 18S in the vagina (A), urethra (B), bladder (C), and rectum (D) of Loxl1 KO and WT mice at different time points after vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, sham cesarean injury, and in pregnant and unmanipulated virgin mice. β indicates a significant difference between pregnant Loxl1 KO and WT mice; # indicates a significant difference between pregnant and virgin mice of the same genotype; * indicates a significant difference between Loxl1 KO and WT vaginal delivered mice at the same postpartum time point; δ indicates a significant difference between vaginal or cesarean delivered and pregnant Loxl1 KO mice; ε indicates a significant difference between vaginal delivered and pregnant WT mice; γ indicates a significant difference between vaginal delivered and cesarean delivered Loxl1 KO mice at the same postpartum time point. In all cases, p < 0.05 was used to indicate a statistically significant difference. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean of data from 6–7 mice. Note that the y-axis scales are different for each panel since comparisons between organs were not made.

The differences in cytokine expression between Loxl1 KO and WT mice in pregnancy persisted after vaginal delivery at the first two time points investigated in both Loxl1 KO and WT mice (1 and 24 hours). Cxcl12 mRNA was significantly increased in the vagina, urethra, bladder, and rectum 1 and 24 hours after delivery in Loxl1 KO mice compared to WT mice (Figure 2). Although 48 hours after delivery, Cxcl12 expression was decreased in the urethra of Loxl1 KO mice compared to WT mice, Cxcl12 mRNA was significantly upregulated in the bladder and rectum. As with Cxcl12, Ccl7 mRNA was significantly upregulated in the vagina, urethra, and rectum 1 and 24 hours after delivery in Loxl1 KO mice compared to WT mice, as well as in the bladder of Loxl1 KO mice 24 hours after delivery (Figure 3). Forty-eight hours after delivery, Ccl7 mRNA was downregulated in the vagina and urethra of Loxl1 KO mice compared to WT mice. Overall, these data illustrate increased cytokine response in Loxl1 KO mice compared to WT mice after vaginal delivery, particularly 1 and 24 hours postpartum.

Vaginal Delivery versus Cesarean Delivery in Loxl1 KO mice

There were no significant differences in Ccl7 and Cxcl12 mRNA expression in any of the pelvic organs of Loxl1 KO mice following cesarean compared to sham cesarean, suggesting that any significant differences observed between cesarean and vaginal delivery are due to the route of delivery (Figures 2 & 3). There were no significant differences in Cxcl12 mRNA expression between cesarean and vaginal delivery in the urethra or vagina. However, Cxcl12 mRNA in the bladder was increased 15 minutes following cesarean compared to vaginal delivery, but decreased 12 hours following cesarean compared to vaginal delivery (Figure 2).

Cxcl12 mRNA was increased in the rectum 1 hour following vaginal delivery compared to cesarean in Loxl1 KO mice (Figure 2). In contrast to Cxcl12 for which there were no significant differences between cesarean and vaginal delivery in the vagina, vaginal delivery resulted in significant upregulation of Ccl7 mRNA 15 minutes and 1 hour postpartum in the vagina and 1 hour postpartum in the urethra compared to cesarean, suggesting increased injury to the vagina as a result of vaginal delivery (Figure 3). However, by 24 hours postpartum, Ccl7 mRNA was significantly decreased in the vagina after vaginal delivery compared to cesarean.

Similar to Cxcl12 mRNA expression in the bladder, Ccl7 mRNA expression was increased after cesarean compared to vaginal delivery in the bladder of Loxl1 KO mice 1 and 4 hours after delivery (Figure 3). Moreover, Ccl7 mRNA was increased in the rectum 12 hours after vaginal delivery compared to cesarean.

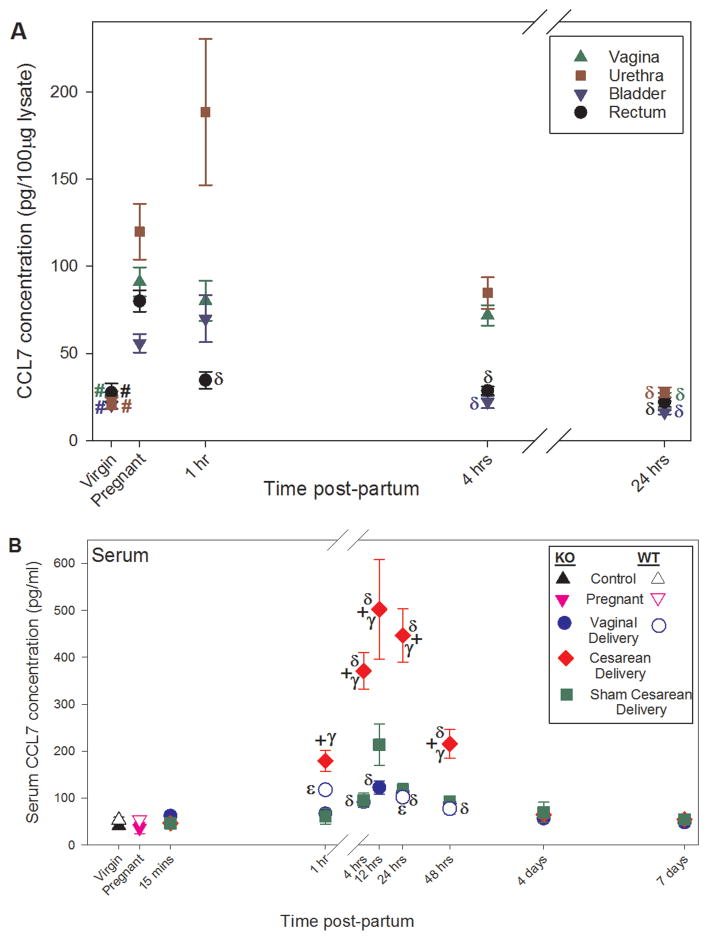

Analysis of serum revealed no baseline differences between WT and Loxl1 KO mice in virgins or pregnant mice (Figure 4). There was a significant increase in CCL7 concentration 1, 4, 12, 24, and 48 hours after cesarean compared to vaginal delivery (Figure 4), likely a result of cytokines being secreted into the blood supply from tissues injured during cesarean surgery (e.g. skin, rectus abdominis, peritoneum, etc). However, there were also significant differences between cesarean and sham cesarean at all these time points.

Figure 4.

CCL7 protein concentration in pelvic organs at different time points after vaginal delivery and in pregnant and unmanipulated virgin Loxl1 KO mice (A) and in serum of Loxl1 KO and WT mice at different time points after vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, sham cesarean injury, and in pregnant and unmanipulated virgin mice (B). # indicates a significant difference between pregnant and virgin mice of the same genotype; δ indicates a significant difference between vaginal or cesarean delivered and pregnant Loxl1 KO mice; ε indicates a significant difference between vaginal delivered and pregnant WT mice; γ indicates a significant difference between vaginal delivered and cesarean delivered Loxl1 KO mice at the same postpartum time point; + indicates a significant difference between cesarean delivered and sham cesarean injury in Loxl1 KO mice at the same time point. In all cases, p < 0.05 was used to indicate a statistically significant difference. Each symbol represents the mean ± standard error of the mean of data from 6–8 mice. Note that the x- and y-axes scales in A and B are different.

Effect of Pregnancy on Cxcl12 and CCL7 in Loxl1 KO and WT mice

Cxcl12 mRNA expression is significantly decreased in the vagina, bladder, and rectum of pregnant WT mice but only in the vagina of pregnant Loxl1 KO mice compared to virgin mice (Figure 2).. In contrast to Cxcl12, Ccl7 mRNA is upregulated in the urethra only of both pregnant Loxl1 KO and WT mice compared to virgin mice, although to a significantly greater extent in Loxl1 KO mice (Figure 3). CCL7 protein concentration was significantly increased in the vagina, urethra, bladder and rectum of pregnant Loxl1 KO mice compared to control (Figure 4). However, these differences do not translate to differences in serum protein of CCL7 in either Loxl1 KO or WT mice.

Effect of Delivery on Cxcl12 and CCL7 in Loxl1 KO and WT mice

Compared with pregnant Loxl1 KO mice, Cxcl12 mRNA is significantly increased 1 hour after vaginal delivery in the urethra and 24 hours after vaginal delivery in the vagina (Figure 2). In contrast, Cxcl12 mRNA is not significantly increased in the urethra and is significantly increased in the vagina of WT mice 48 hours after vaginal delivery compared to pregnant mice (Figure 2). This supports the results noted above that the increase in Cxcl12 gene expression in the urethra and vagina after vaginal delivery is faster and greater in Loxl1 KO mice than in WT mice. Although Ccl7 gene expression significantly increases in the vagina, urethra, bladder and rectum of WT mice as soon as 1 hour after vaginal delivery compared to WT pregnant mice, it increases faster and to a greater extent in the vagina and bladder of Loxl1 KO mice (15 minutes), similar to the pattern observed with Cxcl12 expression (Figure 3). CCL7 had a longer lasting increase in the serum of Loxl1 KO mice after vaginal delivery than in WT mice, compared to pregnant mice (Figure 4).

Discussion

Current treatments for POP do not target the pathophysiology of the disease and surgery is the most frequent management option, often leading to recurrence and sometimes requiring surgical revision.27 Animal models, although imperfect, are crucial to understanding the pathophysiology of POP, assessing markers indicative of childbirth-induced pelvic floor injury, and testing novel therapeutics.10 Research with the Loxl1 KO mouse model in particular is supported by human genetic data implicating abnormal elastin homeostasis in the pathophysiology of POP.14,28 In addition, POP in Loxl1 KO mice simulates the phenotype of POP in women, with vaginal delivery as a major risk factor, often affecting voiding function, and progressing with age.1,11,12

We and others have previously shown that expression and concentration of inflammatory cytokines, such as CCL7 and CXCL12, are altered in response to different levels of tissue injury in animal models and humans.8,18,20–23,25 Although we did not specifically investigate which cell types in pelvic organs produced these cytokines, it is known that smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts secrete these cytokines in response to injury and other manipulations.29–31 Since these cell types abound in pelvic organs, we presume that it is smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts that secreted CCL7 and CXCL12 in our study but confirmation of that is beyond the scope of this study.

In this study, we found that baseline levels (i.e. in virgin mice) of Cxcl12 mRNA in the vagina were significantly higher in Loxl1 KO mice compared to WT mice. Although not statistically significant, Cxcl12 was also increased in the other pelvic organs in virgin KO mice. Therefore, differences in Cxcl12 expression between KO and WT mice at further time points may be due to the higher levels of Cxcl12 at baseline and not necessarily due to alterations in tissue response to pregnancy and parturition.

In contrast, Ccl7 mRNA expression in virgin KO and WT mice was remarkably similar in the vagina and pelvic organs (except for the rectum). Given that the pathogenesis of POP in Loxl1 KO mice is dependent on parity, differences in antepartum and postpartum Ccl7 expression between KO and WT mice could indicate altered response to or degree of tissue injury. Interestingly, pregnancy resulted in a significant increase of both Ccl7 and Cxcl12 in KO mice compared to WT mice, a finding that was consistent among all the pelvic organs analyzed. During pregnancy, pelvic tissues undergo significant remodeling in preparation for childbirth, a process in which LOXL1 and its absence has a significant impact.16,32–35 For example, matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP2), which has been shown to modulate CCL-7, is upregulated late in pregnancy by high levels of estrogen and progesterone.36 Therefore the increase in Ccl7 and Cxcl12 expression in KO mice could be due to differences in tissue remodeling between the two genotypes due to Loxl1 deficiency.

Not surprisingly, Ccl7 expression in the vagina was significantly upregulated early postpartum (0.25 and 1 hr) in vaginal delivery compared to Cesarean delivery in KO mice, suggesting that vaginal delivery induces an injury tissue response even in mice, which, unlike women, generally do not have difficult labors. Although we did not study Cesarean delivery in WT mice in this study, there was also a significant increase in Ccl7 expression in vaginas of WT mice after delivery compared to pregnant mice, although this difference was not as great as in Loxl1 KO mice, suggesting a lesser injury repair response in WT mice. These data also help further explain our previous finding in Loxl1 KO mice showing that vaginal delivery results in higher rates of POP development compared to Cesarean delivery.11

Ccl7 was also upregulated in the urethra after vaginal delivery compared to Cesarean delivery in KO mice. This finding supports our previous work using a simulated childbirth injury model for pelvic floor dysfunction in rats.25,26 Ccl7 mRNA expression is upregulated in the urethra 1 hour after vaginal distension in rats, suggesting that this finding could also be related to ischemia and tissue trauma, not pregnancy or labor alone.22,25 Additionally, this data helps further explain our previous study of lower urinary tract function in Loxl1 KO mice in which we showed that parity significantly contributed to lower leak point pressures.12 Overall, our data suggest that Loxl1 deficiency results in aberrant antepartum and postpartum gene expression responses to pregnancy and parturition that may be exacerbated by vaginal delivery.

In contrast to the vagina and urethra, the bladder presented consistently elevated levels of Ccl7 in animals that underwent surgical procedures (cesarean and sham cesarean). This is most likely a result of urinary retention leading to bladder wall distention and a gene expression response to the resultant injury from anesthesia which suppresses voiding reflexes or use of an opioid–derived postoperative analgesic.37,38 Mice were not catheterized during surgery and, although beyond the scope of this study, this would represent a method to test this mechanism for upregulated Ccl7 in the bladder after cesarean and sham cesarean.

Serum levels of CCL7 in KO and WT mice were not significantly different between pregnant and virgin groups. However, CCL7 serum levels in both KO and WT mice were significantly upregulated after vaginal delivery and after Cesarean delivery in KO mice, compared to the pregnant groups, which shows that parturition-induced tissue injury is detectable in serum. We also found a significant increase in serum levels of CCL7 after Cesarean delivery compared to vaginal delivery in Loxl1 KO mice. Given that Cesarean delivery results in significant tissue injury as a result of surgery, this finding supports the use of CCL7 as a marker for tissue injury.

Vaginal delivery is a major risk factor for POP, but pregnancy also plays an important role.1 Hormonal changes during pregnancy affect physiological parameters such as maternal circulation as well as tissue biomechanics and composition of the uterus and vagina,39 some of which are mediated via MMPs, which contribute to ECM remodeling.36,40 One limitation of this work is that we focused on multiple time points after delivery and only one reproducible time point during pregnancy. Therefore, we may have missed variations in cytokine expression during gestation. In addition, we focused on organs most affected by POP and did not investigate cytokine expression in the uterus and cervix, since we expected cytokine expression in these organs to be dominated by surgical manipulation of cesarean delivery. We also did not investigate other organs not affected by POP.

Due to the limited amount of tissue available from each mouse, particularly from the very small mouse urethra, we only assessed two cytokines in this study, although many others could have been considered for investigation. Future studies could be designed to investigate other cytokines. In addition, rather than using multiple endogenous control genes as we might have, we used only a single housekeeping gene (18S) for RT-PCR studies, which we have found to provide greater reliability with this model than other endogenous control genes.

Likewise, due to the small amounts of tissue available, we did not perform histological or functional lower urinary tract analyses and therefore do not know whether upregulation of cytokines correlates with function or structural changes in tissues. We aimed to characterize the population of Loxl1 KO mice and compare them to the population of WT mice in the expectation that these population-based outcomes could be utilized for comparison to structural and functional assays in future studies. Nonetheless, previous studies have suggested that pelvic floor injuries caused by delivery in Loxl1 KO mice alter the structure of collagen, elastin, and muscles in the urethra and vagina,12,13,17 and as mentioned previously, reduced leak point pressure is correlated with parity in Loxl1 KO mice, which is demonstrative of urethral dysfunction after delivery.12, 13

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that Cxcl12 and Ccl7 mRNA expression is altered in Loxl1 KO compared to WT mice. However, alterations in Cxcl12 expression were not dependent on pregnancy and parturition (as evidenced by differences in virgin animals) and Ccl7 appears to play a more significant role. Differences between KO and WT groups were primarily contained within the pregnancy and later postpartum time points (i.e. 24 and 48 hours). Ccl7 mRNA expression was highly affected by mode of delivery as noted by attenuated expression levels in mice undergoing Cesarean delivery. The urethra and vagina appear to be particularly vulnerable to increased cytokine expression after delivery, providing motivation to explore the cascade of molecular and cellular processes in these organs particularly as they relate to women at risk for pelvic floor disorders. It is possible that upregulation of CCL-7 protein concentration in serum after delivery may serve as an indicator of extent of injury, which could help identify women at high risk of pelvic floor disorders later in life. However, further research is needed to test this hypothesis. These data may also aid in development of novel stem-cell-based therapies, where injury-related homing cytokines can be exploited to direct cells to the sites of injury.41,42

Single Sentence Summary.

Lysyl oxidase like-1 knockout mice, which develop pelvic organ prolapse after delivery have an increased cytokine upregulation response to pregnancy, perhaps because they are less able to reform and re-crosslink stretched elastin to accommodate pups, which may be translatable to humans as an indicator of level of childbirth injury.

Acknowledgments

This project supported in part by NIH R01 HD059859, The Rehabilitation R&D Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and The Cleveland Clinic. The authors would like to thank Bruce Kinley for his management of the mouse colony, Dan Li Lin for surgical expertise, and the Cleveland Clinic BRU for assistance and care of our mouse colony.

Source of Funding: This project supported in part by NIH R01 HD059859, The Rehabilitation R&D Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and The Cleveland Clinic.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Penn has an interest in Juventas, Inc., which has licensed his SDF-1 related technology. Dr. Damaser has a patent pending on stem cell therapeutics for genitourinary dysfunction. The other authors have no real or potential conflict of interest with the results of this study.

References

- 1.Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, et al. Lifetime Risk of Stress Urinary Incontinence or Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–1206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Memon HU, Handa VL. Vaginal childbirth and pelvic floor disorders. Womens Health (Lond Engl ) 2013;9(3):265–277. doi: 10.2217/whe.13.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietz HP. Pelvic floor trauma in childbirth. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53(3):220–230. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller JM, Brandon C, Jacobson JA, et al. MRI findings in patients considered high risk for pelvic floor injury studied serially after vaginal childbirth. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(3):786–791. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parente MP, Jorge RM, Mascarenhas T, et al. Deformation of the pelvic floor muscles during a vaginal delivery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(1):65–71. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hijaz AK, Grimberg KO, Tao M, et al. Stem cell homing factor, CCL7, expression in mouse models of stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(6):356–361. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3182a331a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srikhajon K, Shynlova O, Preechapornprasert A, et al. A New Role for Monocytes in Modulating Myometrial Inflammation During Human Labor. Biol Reprod. 2014 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.114975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo LL, Hijaz A, Kuang M, et al. Over expression of stem cell homing cytokines in urogenital organs following vaginal distention. J Urol. 2007;177(4):1568–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couri BM, Lenis AT, Borazjani A, et al. Animal models of female pelvic organ prolapse: lessons learned. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;7(3):249–260. doi: 10.1586/eog.12.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustilo-Ashby AM, Lee U, Vurbic D, et al. The impact of cesarean delivery on pelvic floor dysfunction in lysyl oxidase like-1 knockout mice. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2010;16(1):21–30. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3181d00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee UJ, Gustilo-Ashby AM, Daneshgari F, et al. Lower urogenital tract anatomical and functional phenotype in lysyl oxidase like-1 knockout mice resembles female pelvic floor dysfunction in humans. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295(2):F545–F555. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00063.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu G, Daneshgari F, Li M, et al. Bladder and urethral function in pelvic organ prolapsed lysyl oxidase like-1 knockout mice. BJU Int. 2007;100(2):414–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao BH, Zhou JH. Decreased expression of elastin, fibulin-5 and lysyl oxidase-like 1 in the uterosacral ligaments of postmenopausal women with pelvic organ prolapse. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(6):925–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mecham RP. Elastin synthesis and fiber assembly. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;624:137–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb17013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alperin M, Debes K, Abramowitch S, et al. LOXL1 deficiency negatively impacts the biomechanical properties of the mouse vagina and supportive tissues. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(7):977–986. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0561-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couri BM, Borazjani A, Lenis AT, et al. Validation of Genetically Matched Wild Type Strain and Lysyl Oxidase-Like 1 Knockout Mouse Model of Pelvic Organ Prolspe. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(5):287–292. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyoneva S, Ransohoff RM. Inflammatory reaction after traumatic brain injury: therapeutic potential of targeting cell-cell communication by chemokines. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholas J, Voss JG, Tsuji J, et al. Time course of chemokine expression and leukocyte infiltration after acute skeletal muscle injury in mice. Innate Immun. 2015;21(3):266–274. doi: 10.1177/1753425914527326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenk S, Mal N, Finan A, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-3 is a myocardial mesenchymal stem cell homing factor. Stem Cells. 2007;25(1):245–251. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinohara K, Greenfield S, Pan H, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 and monocyte chemotactic protein-3 improve recruitment of osteogenic cells into sites of musculoskeletal repair. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(7):1064–1069. doi: 10.1002/jor.21374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vricella GJ, Tao M, Altuntas CZ, et al. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein 3 following simulated birth trauma in a murine model of obesity. Urology. 2010;76(6):1517. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.07.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wan X, Xia W, Gendoo Y, et al. Upregulation of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) is associated with macrophage infiltration in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal U, Ghalayini W, Dong F, et al. Role of cardiac myocyte CXCR4 expression in development and left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2010;107(5):667–676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenis AT, Kuang M, Woo LL, et al. Impact of parturition on chemokine homing factor expression in the vaginal distention model of stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2013;189(4):1588–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood HM, Kuang M, Woo L, et al. Cytokine expression after vaginal distention of different durations in virgin Sprague-Dawley rats. J Urol. 2008;180(2):753–759. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, et al. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):367–373. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318195888d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung HJ, Jeon MJ, Yim GW, et al. Changes in expression of fibulin-5 and lysyl oxidase-like 1 associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145(1):117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takemura M, Itoh H, Sagawa N, et al. Cyclic mechanical stretch augments both interleukin-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein-3 production in the cultured human uterine cervical fibroblast cells. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2004;10(8):573–580. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavalla F, Osorio C, Paredes R, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases regulate extracellular levels of SDF-1/CXCL12, IL-6 and VEGF in hydrogen peroxide-stimulated human periodontal ligament fibroblasts. Cytokine. 2015;73:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lözer K, Döpping S, Connert S, et al. Mouse aorta smooth muscle cells differentiate into lymphoid tissue organizer-like cells on combined turmor necrosis factor receptor-1/Lymphotoxin beta-receptor NF-kappa beta signaling. Aterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:395–402. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.191395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alperin M, Kaddis T, Pichika R, et al. Pregnancy-induced adaptations in intramuscular extracellular matrix of rat pelvic floor muscles. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.02.018. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alperin M, Lawley DM, Esparza MC, et al. Pregnancy-induced adaptations in the intrinsic structure of rat pelvic floor muscles. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;213(2):191.e1–191.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feola A, Moalli P, Alperin M, et al. Impact of pregnancy and vaginal delivery on the passive and active mechanics of the rat vagina. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2011;39(1):549–558. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grob AT, Withagen MI, van de Waarsenburg MK, Schweitzer KJ, van der Vaart CH. Changes in the man echogenicity and area of the puborectalis muscle during pregnancy and postpartum. International Urogynecology Journal. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2905-4. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slavik L, Prochazkova J, Prochazka M, et al. The pathophysiology of endothelial function in pregnancy and the usefulness of endothelial markers. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2011;155(4):333–337. doi: 10.5507/bp.2011.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moheban AA, Chang HH, Havton LA. The suitability of propofol compared with urethane for anesthesia during urodynamic studies in rats. Journal of the American Association Laboratory Animal Science. 2016;55(1):89–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang HY, Havton LA. Differential effects of urethane and isoflurane on external urethral sphincter electromyography and cystometry in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295(4):F1248–F1253. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90259.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ouzounian JG, Elkayam U. Physiologic changes during normal pregnancy and delivery. Cardiol Clin. 2012;30(3):317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dang Y, Li W, Tran V, et al. EMMPRIN-mediated induction of uterine and vascular matrix metalloproteinases during pregnancy and in response to estrogen and progesterone. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86(6):734–747. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bousquenaud M, Schwartz C, Leonard F, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein 3 is a homing factor for circulating angiogenic cells. Cardiovascular Research. 2012;94(3):519–525. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng M, Huang K, Zhou J, et al. A critical role of Src familiy kinase in SDF-1/CXCR4-mediated bone-marrow progenitor cell recruitment to the ischemic heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;81:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]