Abstract

The purpose of this case report is to describe the value of musculoskeletal ultrasound (US) in diagnosing both distal intersection syndrome (DIS) and rupture of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon in the same patient. A 38-year-old female presented for evaluation of a painful bump of unknown etiology on the dorsolateral aspect of her non-dominant wrist. US demonstrated tenosynovitis distal to Lister's tubercle of the EPL and extensor carpi radialis tendon sheaths, consistent with DIS. Immobilization therapy was employed, during which time the patient suffered rupture of the EPL tendon. Follow-up US examination confirmed this additional diagnosis. Characteristic US findings of DIS and EPL tendon rupture were observed. Surgical intervention was required and the patient recovered without complication. Although EPL rupture is relatively common in the literature, DIS is rare. This is the first known case of imaging-proven DIS progressing to EPL tendon rupture. This case underscores the value of US as a widely available, cost effective, and dynamic imaging modality for evaluation of wrist complaints.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40477-016-0223-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Wrist, Tendons, Tenosynovitis, Overuse syndrome, Intersection syndrome

Sommario

Lo scopo di questo caso clinico è quello di descrivere l'utilità dell’ecografia (US) muscolo-scheletrica nella diagnosi della sindrome da intersezione distale (DIS) e della rottura del tendine estensore lungo del pollice (EPL) in uno stesso paziente. Il caso riguarda una donna di 38 anni, valutatain merito ad una tumefazione dolente di eziologia sconosciuta sulla superficie dorsolaterale del polso non dominante. L’ecografia dimostrava una tenosinovite distale al tubercolo di Lister della EPL e delle guaine tendinee dell’estensore radiale del carpo, coerente con la diagnosi di DIS. Tale lesione è stata trattata con immobilizzazione dell’arto, durante il quale la paziente ha subito rottura del tendine EPL. L’esame ecografico di follow-up ha confermato questa ulteriore diagnosi. L’ecografia ha quindi evidenziato reperti caratteristici della DIS e di rottura del tendine EPL, sulla base dei quali la paziente è stata sottoposta ad intervento chirurgico che è stato effettuato senza complicazioni, permettendo il recupero funzionale dell’arto. Anche se la rottura del EPL è relativamente comune nella letteratura, la DIS è rara. Questo è il primo caso a noi noto di imagingche dimostra la DIS con progressione verso rottura del tendine del EPL. Questo caso sottolinea il valore dell’ecografia come modalità di diagnostica di imaging dinamico,ampiamente disponibile ed economica per valutare le lesioni del polso.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40477-016-0223-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Distal intersection syndrome (DIS) can be defined as tenosynovitis occurring at a specific anatomic site where the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon crosses over the extensor carpi radialis tendons [1]. It is rare compared to the more common proximal intersection syndrome and de Quervain stenosing tenosynovitis [2]. These three distinct entities occur on the dorsolateral aspect of the wrist within 3–5 cm of one another (Fig. 1). Clinical differentiation can be challenging, therefore imaging is useful to determine the specific anatomy involved. Furthermore, it has been postulated that the synovitis may cause rupture of the EPL tendon [1]. Thus, imaging is also useful to exclude this as a complication.

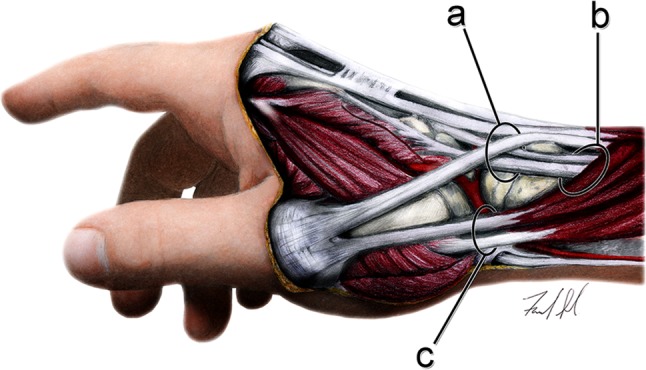

Fig. 1.

Illustration demonstrates the anatomy involved in selected differential diagnoses: (a) anatomic location of distal intersection syndrome; the extensor pollicis longus tendon can be seen as it alters its course sharply around Lister’s tubercle; (b) anatomic location of proximal intersection syndrome; (c) anatomic location of de Quervain stenosing tenosynovitis. Appreciate the close proximity of the involved anatomy and the potential for clinical misdiagnosis

Few reports of DIS in non-rheumatoid patients exist in the literature. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing ultrasonographic (US) findings of DIS prior to and after rupture of the EPL tendon in the same patient. Also, the specific findings in this case suggest that more aggressive treatment may be necessary to avoid rupture of the EPL tendon in patients who have been diagnosed with DIS.

Case report

The patient discussed in the following case report gave written consent for educational usage of de-identified images and clinical data.

A 38-year-old female presented with a painful bump on the dorsolateral aspect of her non-dominant hand, approximately 1 cm distal to the wrist crease. There were no swollen joints near the bump and she was non-febrile. Ganglion cyst was suspected and musculoskeletal US was ordered for confirmation. Sonographic examination (GE Logiq E9, GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI)was performed using two, high-frequency linear transducers (ML6-15 operating at 12 MHz and L8-18i operating at 15 MHz) utilizing a standardized protocol which includes imaging of the tendons at the wrist in two perpendicular planes. The US examination demonstrated anechoic fluid within the sheaths of the second extensor compartment (extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi radialis brevis tendons) and EPL tendon at the third extensor compartment distal to Lister’s tubercle (Fig. 2). Marked hyperemia was noted during power Doppler examination (Fig. 2). These sonographic findings are consistent with tenosynovitis [3]. Importantly, the EPL tendon was intact during the first US examination, was not tendinopathic, and was clearly seen crossing over both extensor carpi radialis tendons (Fig. 3a, Online Resource 1). Subsequent clinical lab exam ruled out infection or rheumatologic disease as potential etiologies (white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein were all within normal limits). A diagnosis of DIS was established based on the US findings and the patient was referred to a hand specialist who prescribed pain medication and a wrist splint. Approximately one week into wearing the splint, the patient had acute exacerbation of her pain and subsequent difficulty extending her thumb. She returned to the hand specialist and was diagnosed clinically with EPL tendon rupture. A follow-up US examination was performed approximately one week later and confirmed the diagnosis (Fig. 3b, Online Resource 2). During this second US examination, absence of movement of the retracted proximal stump of the EPL tendon was noted during passive flexion and extension of the thumb. Surgical repair of the EPL tendon was performed using an extensor indices transfer and the patient recovered without incident. Another US examination performed several weeks after the surgery clearly demonstrated the repaired EPL tendon crossing over the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis tendons, as well as movement of the repaired EPL tendon during passive movement of the thumb.

Fig. 2.

Sonographic examination in the axial plane at the level of the distal intersection where the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon crosses over the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) tendons. Note the effusions within the tendon sheaths of the EPL, ECRL, and ECRB along with prominent hyperemia consistent with tenosynovitis. These sonographic findings are consistent with the diagnosis of distal intersection syndrome

Fig. 3.

Sonographic examination in the axial plane prior to (a) and after (b) EPL tendon rupture. Note the EPL tendon crossing over the ECRB tendon at the distal intersection (a). After EPL tendon rupture (b) there is absence of the EPL tendon superficial to the ECRB tendon. Fluid (*) fills the empty sheath of the EPL tendon. The proximal and distal stumps of the EPL tendon were identified on other images (not shown)

Discussion

The distal intersection is defined anatomically where the EPL tendon crosses over the extensor carpi radialis tendons distal to Lister’s tubercle. Lister’s tubercle acts as a pulley for the EPL tendon, providing leverage, but also contributing to a mechanically disadvantageous setting in which the EPL tendon is predisposed to injury. Distal intersection syndrome is characterized by tenosynovitis at this specific anatomic location secondary to tendon overuse and friction from this anatomic predisposition [1, 4]. Etiology of EPL tendon rupture is not fully understood, but one study suggests that effusion in an already confined space contributes to avascular necrosis of the tendon [5].

At least 26 cases of DIS are identified in the English literature in non-rheumatoid patients [1, 4, 6, 7]. Of those, only three cases present sonographic findings. In all 26 of these cases, the patients responded to conservative treatment and no EPL tendon rupture was reported. A search of the literature shows the term “intersection syndrome” to be synonymous with proximal intersection syndrome. Distal intersection syndrome is rarely mentioned. However, the term “spontaneous rupture of the EPL tendon” is commonly used. Although it has been reasoned that DIS may cause rupture of the EPL tendon as it is at risk when changing course over Lister’s tubercle [1], we report the first case of imaging-proven DIS progressing to EPL tendon rupture. Therefore, it is likely that “spontaneous rupture of the EPL tendon” may be preceded, at least in some cases, by DIS. This emphasizes the value of achieving an accurate diagnosis as clinicians may want to consider more aggressive forms of treatment than simply brace therapy when DIS is encountered. Also, by recognizing DIS as a distinct entity, both radiologists and clinicians may begin to gain deeper insight into the pathophysiology of EPL tendon rupture because currently differentiating proximal intersection syndrome, DIS, and spontaneous EPL tendon rupture in the literature is challenging.

The differential diagnosis for radial-sided, dorsal wrist pain without a history of trauma includes DIS, de Quervain stenosing tenosynovitis, proximal intersection syndrome, ganglion cyst, radial nerve entrapment (Wartenberg’s syndrome), and osteoarthritis (Fig. 1) [6, 8–10].

Tenosynovitis is a prominent feature of DIS and may lead to rupture of the EPL tendon [1]. While this may be diagnosed clinically, advanced imaging adds to the clinical picture and confirms the need for surgical intervention [11]. Hyperemia during power Doppler examination was not specifically mentioned as a feature of tenosynovitis in the few cases of DIS described using US [6]. It was a prominent finding in our case in the first US examination during active DIS, but was markedly reduced at the post-rupture US examination. Considering the normal appearance of the EPL tendon itself during the first US examination, it is thought that the hyperemia may have contributed to the tendon rupture. Neovascularity has been demonstrated as a pain generator in tendinopathy [12]. What is unknown and is deserving of further investigation is the direct relationship between hyperemia and subsequent tendon failure.

Although DIS may respond to conservative care [1], an EPL tendon rupture requires surgical intervention, underscoring the importance of timely and accurate diagnosis [7, 13]. None of the 26 DIS cases reported in the literature went on to rupture the EPL tendon. Some were treated conservatively, while others were treated more aggressively with synovectomy [1, 4, 6, 7]. Since tenosynovitis involving the tendons of the second extensor compartment was a finding in some cases of EPL tendon rupture [13, 14], it is possible that DIS preceded the rupture in those cases. Tenosynovitis of those tendons was present in our case before and after EPL tendon rupture. An anatomic communication between the tendons of the second and third compartments has been established [4]. As a result of this communication, it is possible that isolated tendinitis with tenosynovitis of either compartment two or three may “spill-over” synovial fluid into the other compartment; this is a situation different from DIS, in which the intersection of the two compartments produces friction induced tenosynovitis of both compartments [1]. The images of our patient were of DIS, as the EPL tendon was unremarkable, and there was concomitant hyperemia of the fluid within the second extensor compartment. If our case had been imaged only after the EPL tendon rupture and not before as well, it would have looked similar to other cases of isolated EPL tendon rupture [13, 14] and would not have been diagnosed as DIS.

It is also possible that rupture could have been avoided in our patient with more aggressive treatment. Perhaps the presence of hyperemia should be considered when determining treatment. If that is the case, then US is ideally suited for the workup of these patients and should be considered as a first line imaging modality. Assessment by US is less costly than other imaging modalities and can directly visualize the EPL tendon. The dynamic capability also allows confirmation and surgical planning in cases of EPL tendon rupture [11, 13]. Sonographic findings specific to DIS [2, 6] and of EPL tendon rupture have been previously described [11, 13].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which was not performed in our case, may demonstrate characteristic findings of tenosynovitis isolated to the involved tendons distal to Lister’s tubercle [1]. However, the anatomy of the EPL tendon itself is difficult to examine with MRI, as the tendon is very flat and may not be well depicted. Also, the obliquity of the tendon’s course results in false positives from magic angle artifact [13]. Multiple cases of DIS were missed prospectively with MRI, but then identified retrospectively [4]. Another case was missed twice with MRI, but then identified utilizing US (Boettcher, B. and J. Brault. Twice missed on MRI—atraumatic rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon after casting for distal radius fracture in a healthy 46-year-old: a case report; Abstracts PM R 7 [2015] S83–S222). Specialized coils and slice planes may help, but are not routine and are time-consuming [13]. Other entities in the differential may be imaged well utilizing MRI, but may still be missed if specialized imaging protocols are not employed [15]. Because DIS is a rare diagnosis, there are no statistics on accuracy of diagnostic studies.

In conclusion, US provided a non-invasive and economical method in the primary diagnosis of DIS and also to confirm the clinical diagnosis of EPL tendon rupture in this case. It seems likely that DIS is considered a rare diagnosis because it is simply missed when in fact it may be the predisposing agent in cases of “spontaneous” EPL tendon rupture. This may be because it is misdiagnosed clinically but still improves with treatment, because it is not seen with MRI, or because it is imaged after the EPL tendon has already ruptured and thus is not recognized as DIS. This case suggests that more aggressive treatment is necessary when hyperemia is present, but more studies are necessary.

Limitations

Because this is a report of one case, generalization of the diagnostic findings will not necessarily apply to a larger population.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40477-016-0223-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Parellada AJ, Gopez AG, Morrison WB, Sweet S, Leinberry CF, Reiter SB, Kohn M. Distal intersection tenosynovitis of the wrist: a lesser-known extensor tendinopathy with characteristic MR imaging features. Skelet Radiol. 2007;36(3):203–208. doi: 10.1007/s00256-006-0238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Draghi F, Bortolotto C, Draghi AG, Gregoli B. Musculoskeletal sonography for evaluation of anatomic variations of extensor tendon synovial sheaths in the wrist. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34(8):1445–1452. doi: 10.7863/ultra.34.8.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakefield RJ, Balint PV, Szkudlarek M, Filippucci E, Backhaus M, D’Agostino MA, Sanchez EN, Iagnocco A, Schmidt WA, Bruyn GA, Kane D, O’Connor PJ, Manger B, Joshua F, Koski J, Grassi W, Lassere MN, Swen N, Kainberger F, Klauser A, Ostergaard M, Brown AK, Machold KP, Conaghan PG, Group OSI Musculoskeletal ultrasound including definitions for ultrasonographic pathology. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(12):2485–2487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cvitanic OA, Henzie GM, Adham M. Communicating foramen between the tendon sheaths of the extensor carpi radialis brevis and extensor pollicis longus muscles: imaging of cadavers and patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(5):1190–1197. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engkvist O, Lundborg G. Rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon after fracture of the lower end of the radius—a clinical and microangiographic study. Hand. 1979;11(1):76–86. doi: 10.1016/S0072-968X(79)80015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draghi F, Bortolotto C. Intersection syndrome: ultrasound imaging. Skelet Radiol. 2014;43(3):283–287. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang HW, Strauch RJ. Extensor pollicis longus tenosynovitis: a case report and review of the literature. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25(3):577–579. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.5988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abe Y, Tsue K, Nagai E, Katsube K, Miyoshi T. Extensor pollicis longus tenosynovitis mimicking de Quervain’s disease because of its course through the first extensor compartment: a report of 2 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(2):225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Maeseneer M, Marcelis S, Jager T, Girard C, Gest T, Jamadar D. Spectrum of normal and pathologic findings in the region of the first extensor compartment of the wrist: sonographic findings and correlations with dissections. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28(6):779–786. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishijo K, Kotani H, Miki T, Senzoku F, Ueo T. Unusual course of the extensor pollicis longus tendon associated with tenosynovitis, presenting as de Quervain disease–a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(4):426–428. doi: 10.1080/000164700317393484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santiago FR, Plazas PG, Fernandez JM. Sonography findings in tears of the extensor pollicis longus tendon and correlation with CT, MRI and surgical findings. Eur J Radiol. 2008;66(1):112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alfredson H, Ohberg L, Forsgren S. Is vasculo-neural ingrowth the cause of pain in chronic Achilles tendinosis? An investigation using ultrasonography and colour Doppler, immunohistochemistry, and diagnostic injections. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11(5):334–338. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Maeseneer M, Marcelis S, Osteaux M, Jager T, Machiels F, Van Roy P. Sonography of a rupture of the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus muscle: initial clinical experience and correlation with findings at cadaveric dissection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(1):175–179. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonatz E, Kramer TD, Masear VR. Rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1996;25(2):118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lima JE, Kim HJ, Albertotti F, Resnick D. Intersection syndrome: MR imaging with anatomic comparison of the distal forearm. Skelet Radiol. 2004;33(11):627–631. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.