Highlights

-

•

Incisional hernia is not an uncommon complication after abdominal operation.

-

•

Mesh migration and erosion causing vesico-cutaneous fistula and subsequent necrotizing fasciitis is uncommon.

-

•

We hereby report a case of abdominal wall necrotizing fasciitis 21 months after laparoscopic incisional hernia repair in lower midline with dual mesh, due to mesh migration and erosion into urinary bladder, resulting in fistulation between bladder and abdominal wall.

-

•

Mesh erosion to viscera can cause severe complication. Its risk should be balanced and discussed with patient with full consent.

Keywords: Incisional hernia mesh repair, Composite mesh, Mesh migration, Urinary bladder fistula, Necrotizing fasciitis

Abstract

Introduction

Incisional hernia is not an uncommon complication after abdominal operation, and laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with mesh is commonly performed nowadays. It is thought to have less complication compare to the traditional open repair, yet late complication is still observed occasionally and can be disastrous.

Case report

We hereby report a case of abdominal wall necrotizing fasciitis 21 months after laparoscopic incisional hernia repair in lower midline with dual mesh, due to mesh migration and erosion into urinary bladder, resulting in fistulation between bladder and abdominal wall. Repeated debridement and removal of mesh was required for sepsis control and the patient required intensive care support due to multi-organ failure. Subsequent repair of urinary bladder and abdominoplasty was performed after condition stabilized.

Conclusion

This case was the first reported incident with bladder erosion by dual mesh causing vesico-cutaneous fistula complicated with necrotizing fasciitis. Although dual mesh theoretically reduces the risk of mesh erosion, mesh erosion to viscera can still happen and cause severe complication. Its risk should be balanced and discussed with patient with full consent.

1. Introduction

Incisional hernia is among the most common complications of abdominal surgery. The incidence of incisional hernia is 10–15% and recurrence rate is 20–45% [1], [2]. There is increasing popularity of ventral hernia repair with mesh products. However, occasional complications may still occur. Mesh migration though uncommon but was reported in patients with surgical history of either open or laparoscopic herniorrhaphy with mesh [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Here we describe a case of abdominal wall necrotizing fasciitis 21 months after laparoscopic incisional hernia repair in lower midline with dual mesh, due to mesh migration and erosion into urinary bladder, resulting in fistulation between bladder and abdominal wall. This is the first reported case of incisional hernia complication presented as necrotizing fasciitis. This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [9].

2. Case report

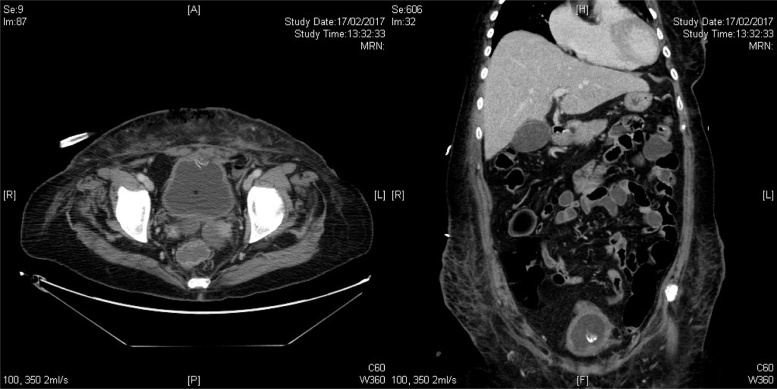

Miss T is a 62-year-old lady with history of total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for uterine fibroid, endometrial polyp and ovarian cyst years ago, and the resulting lower midline wound was complicated with incisional hernia. She has no drug allergy nor psychosocial history. Laparoscopic dual mesh repair (20 × 20 cm) of the 5 cm fascial defect at inferior aspect of wound was performed on 14 May 2015. We applied the circular Ventralight ST Mesh with an uncoated lightweight monofilament polypropylene mesh on the anterior side with an absorbable hydrogel barrier based on Sepra® Technology on the posterior side. 21 months later she was admitted for severe abdominal pain with abdominal wall tenderness and erythema. Urgent contrast Computed Tomography of abdomen and pelvis showed urinary bladder was perforated at its anterior wall, connecting to a 8 × 3 × 4 cm collection with partial rim enhancement in the subcutaneous region of lower abdomen. Small calcification noted in the anterior bladder wall and in the collection suspicious of foreign body. Surgical emphysema was noted in lower abdomen (Fig. 1). Overall impression was NECROTISING FASCIITIS.

Fig. 1.

CT scan showing a 8 × 3 × 4 cm rim-enhancing collection in the subcutaneous region of lower abdomen. Small calcification noted in the anterior bladder wall and in the collection suspicious of foreign body.

Emergency debridement of unhealthy skin and subcutaneous tissue was done by general surgery specialist. Intra-operation cystoscopy performed and the mesh was found to have eroded into the urinary bladder with formation of vesico-cutaneous fistula, therefore urethral catheter was inserted for drainage. Patient developed septic shock requiring intensive care, inotropic support and mechanical ventilation. Her sepsis subsequently improved after the initial debridement and antibiotics (Fig. 2) Repeated debridement was performed. Removal of mesh and repair of 2 × 2 cm urinary bladder defect was done one week later (Fig. 3). Abdominoplasty was performed after condition stabilized at 4 weeks after the first operation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Photo showing the wound after the first debridement.

Fig. 3.

Removal of mesh and repair of urinary bladder was performed.

Fig. 4.

Abdminoplasty was performed 4 weeks after first debridement.

Her condition was satisfactory after abdominoplasty and was transferred to general ward, with cystogram confirmed no leakage from urinary bladder. She could tolerate the treatment all along and was then transferred to rehabilitation bed for further training. The wound was also healing well on latest follow-up and she was happy with her condition.

3. Discussion

Advanced age, obesity, intra-abdominal ascites, pregnancy, malnutrition, chronic pulmonary disease and corticosteroid are leading risk factors for the development of incisional hernia [10], [11]. Ventral hernias are the second most common type of hernia, second only to inguinal hernias. By the advent of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair in 1993, not only the recurrence rate dropped from 30% to 4–16%, but also the complications were minimized due to minimal tissue dissection. Mesh repair is particularly important for incisional hernia with a diameter greater than 4 cm as the risk of recurrence is higher as the width increases [12].

Dual (Composite) meshes are manufactured with different materials on each surface. The more inert mesh material is intended to prevent adhesions with the underlying viscera. Migration of mesh has long been recognized as a potential complication though there are only few reported cases of migration of dual mesh after inguinal or incisional hernia repair. This case is the first in Hong Kong and presentation as necrotizing fasciitis is the first around the world. Avill and Agrawal proposed 2 possible mechanisms for mesh migration: primary mechanical migration and secondary migration as a result of erosion of the surrounding tissue. The former are mere displacements of the mesh along paths of least resistance brought about by either inadequate fixation or by external displacing forces. Secondary migrations are slow and gradual movement of mesh through transanatomic planes. These are secondary to foreign-body reaction-induced erosion [13]. In this case the migrated mesh transversed different anatomic planes and created a vesico-cutaneous fistula, which implies secondary migration more likely.

The method of fixation may affect migration rates by altering the tensile strength and degree of movement of the mesh. However, the nature of the biomaterial is also important as it affects the extent and degree of interaction with the surrounding tissue. Biological agents are being used with increasing frequency in abdominal wall hernias, where they have been shown to reduce foreign body reaction and potential complications secondary to infections [14]. The size, shape and positioning of the mesh may also be significant.

In this case surgical debridement with removal of mesh and repair of urinary bladder is inevitable due to the extensive involvement of cutaneous tissue. Abdominoplasty is performed when tissue healing is satisfactory after repeated debridement.

4. Conclusion

Mesh migration and erosion is a rare complication of incisional hernia repair. There is no clear cause of this complication. Although dual mesh theoretically reduces the risk of mesh erosion, mesh erosion to viscera can still happen and cause severe complication. Its risk should be balanced and discussed with patient with full consent.

Conflicts of interest

No.

Funding

No.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Consent was obtained from the corresponding patient.

Author contribution

Amy Siu Yan Kok: journal search, writing the paper.

Tommy Siu Hong Cheung: journal search, writing the paper.

Dennis Chin Tou Lam: journal search.

Wilson Hoi Chak Chan: journal search.

Sharon Wing Wai Chan: proof read and adviser.

Tam Lin Chow: proof read and advisor.

Guarantor

Amy Siu Yan Kok.

References

- 1.Mudge M., Hughes L.E. Incisional hernia: a 10 year prospective study of incidence and attitudes. Br. J. Surg. 1985;72(1):70–71. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kingsnorth A., LeBlanc K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet. 2003;362(9395):1561–1571. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal A., Avill R. Mesh migration following repair of inguinal hernia: a case report and review of literature. Hernia. 2006;10(1):79–82. doi: 10.1007/s10029-005-0024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamouda A., Kennedy J., Grant N., Nigam A., Karanjia N. Mesh erosion into the urinary bladder following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: is this the tip of the iceberg? Hernia. 2010;14(3):317–319. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hume R.H., Bour J. Mesh migration following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. J. Laparoendosc. Surg. 1996;6(5):333–335. doi: 10.1089/lps.1996.6.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurukahvecioglu O., Ege B., Yazicioglu O., Tezel E., Ersoy E. Polytetrafluoroethylene prosthesis migration into the bladder after laparoscopic hernia repair: a case report. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2007;17(5):474–476. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3180f62f56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo D.J., Bilimoria K.Y., Pugh C.M. Bowel complications after prolene hernia system (PHS) repair: a case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2008;12(4):437–440. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy J.W., Misra D.C., Silverglide B. Sigmoid colon fistula secondary to Perfix-plug, left inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. 2006;10(5):436–438. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., The SCARE Group The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsend C.M., Beauchamp R.D., Evers M.B., Mattox K.L. Hernias. In: Malangoni M.A., Rosen M.J., editors. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 19th edition. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia, Pa, USA: 2012. section X, chapter 46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subramanian A., Clapps M.I., Hicks S.C., Award S.S., Liang M.K. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: primary versus secondary hernias. J. Surg. Res. 2013;181(1):e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramanian A., Clapp M.L., Hicks S.C., Awad S.S., Liang M.K. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair primary versus secondary hernias. J. Surg. Res. 2013;181:e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agrawal A., Avill R. Mesh migration following repair of inguinal hernia: a case report and review of literature. Hernia. 2006;10(1):79–82. doi: 10.1007/s10029-005-0024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kharief Ahmed. Mesh migration into colonic lumen post abdominal hernia repair: a case report. Austin J. Surg. 2017;4(1):1095. [Google Scholar]