Abstract

Apremilast, an oral, small‐molecule phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, works intracellularly within immune cells to regulate inflammatory mediators. This phase 2b randomized, placebo‐controlled study evaluated efficacy and safety of apremilast among Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. In total, 254 patients were randomized to placebo, apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. (apremilast 20) or apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. (apremilast 30) through week 16; thereafter, all placebo patients were re‐randomized to apremilast 20 or 30 through week 68. Efficacy assessments included achievement of 75% or more reduction from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI‐75; primary) and achievement of static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA; secondary) score of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) at week 16. Safety was assessed through week 68. At week 16, PASI‐75 response rates were 7.1% (placebo), 23.5% (apremilast 20; P = 0.0032 vs placebo) and 28.2% (apremilast 30; P = 0.0003 vs placebo); sPGA response rates (score of 0 or 1) were 8.8% (placebo), 23.9% (apremilast 20; P = 0.0165 vs placebo) and 29.6% (apremilast 30; P = 0.0020 vs placebo). Responses were maintained with apremilast through week 68. Most common adverse events (AEs) with placebo, apremilast 20 and apremilast 30 (0–16 weeks) were nasopharyngitis (8.3%, 11.8%, 11.8%), diarrhea (1.2%, 8.2%, 9.4%), and abdominal discomfort (1.2%, 1.2%, 7.1%), respectively. Exposure‐adjusted incidence of these AEs did not increase with continued apremilast treatment (up to 68 weeks). Apremilast demonstrated efficacy and safety in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis through 68 weeks that was generally consistent with prior studies.

Keywords: apremilast, phosphodiesterase 4, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, psoriasis, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

Introduction

Psoriasis, a chronic systemic inflammatory disease involving the skin, is the result of dysregulated immune responses.1 In Japan, psoriasis is reported to affect approximately 0.34% of the population,2 similar to prevalence reported in other Asian populations, but lower than the 1–3% seen in other global populations.3 In Japan, approximately 60% of total psoriasis cases occur in men.2 Because psoriasis is a chronic disease, the long‐term treatment goals are to maximize symptom control while minimizing safety risks. For patients with moderate to severe disease, however, the clinical benefits of currently available systemic treatment options are often compromised by safety and tolerability issues.4, 5

Apremilast (Otezla; Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ, USA) is an oral, small‐molecule phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that works within immune cells to regulate the production of pro‐inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin (IL)‐17, IL‐23 and tumor necrosis factor‐α, and anti‐inflammatory mediators implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.6, 7, 8 In phase 2 clinical studies in patients with psoriasis, apremilast decreased lesional skin epidermal thickness, inflammatory cell infiltration and the expression of pro‐inflammatory genes, including IL‐17A, IL‐23 and IL‐22.9 Phase 2 and 3 studies have demonstrated apremilast is effective, has an acceptable safety profile, and is generally well tolerated in patients with plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 In a phase 2b dose‐finding study conducted in the United States and Canada, apremilast administered p.o. at 20 or 30 mg b.i.d. was efficacious, safe and well tolerated in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.10 This report describes the results of a phase 2b randomized, placebo‐controlled study that evaluated the efficacy and safety of apremilast in the treatment of Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis for up to 68 weeks.

Methods

Study design and treatment

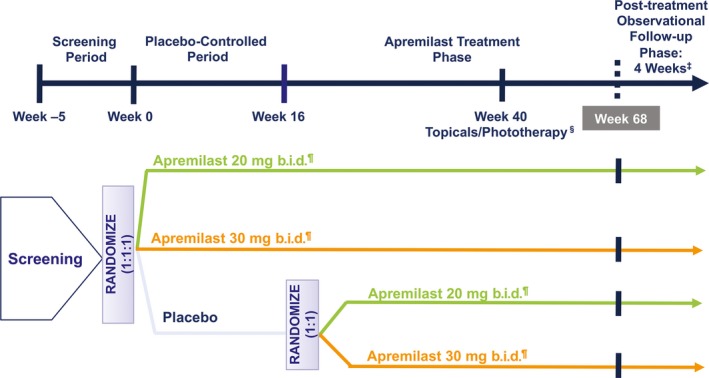

This phase 2b multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study was conducted in Japanese patients at academic and community hospitals. The first patient study visit was on 9 July 2013, and the last patient completed the week 72 study visit on 17 December 2015. The study comprised four phases: a pre‐randomization screening period, two treatment periods (placebo‐controlled period and apremilast treatment phase), and a 4‐week post‐treatment observational follow‐up period (Fig. 1). After the screening period, eligible patients began a 16‐week placebo‐controlled period and were randomized via a centralized interactive web response system or interactive voice response system (1:1:1) to placebo, apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. or apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. Doses were titrated in 10‐mg daily increments (beginning with 10 mg daily) over the first week of treatment to mitigate potential gastrointestinal adverse events (AEs); all patients reached the target dose by day 6. At week 16, patients entered the apremilast treatment phase, in which patients in the apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. and 30 mg b.i.d. groups continued treatment and placebo patients were re‐randomized (1:1) to either apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. or 30 mg b.i.d., with titration; apremilast dosing was maintained from weeks 16 to 68. For patients who switched from placebo, apremilast was titrated in 10‐mg daily increments (beginning with 10 mg daily) over the first week of this period. For patients who did not achieve a 50% or more reduction from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (PASI‐50) by week 40 (i.e. non‐responders), topical therapies and/or ultraviolet B therapy could be added at the discretion of the investigator.

Figure 1.

Study design. ‡Every patient was to enter a 4‐week post‐treatment observational follow‐up phase at the time the patient completed or discontinued the study. §Starting at week 40, all non‐responders (<PASI‐50) had the option of adding topical therapies and/or phototherapy, at the discretion of the investigator. ¶Doses of apremilast were titrated during the first week of administration and at week 16 when placebo patients were switched to apremilast. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PASI‐50, ≥50% reduction from baseline in PASI score.

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and/or independent ethics committee at each investigational center. All patients provided written informed consent at the first screening visit. The study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01988103).

Patients

Adults aged 20 years or more were eligible if they were diagnosed with chronic moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (PASI score ≥12, body surface area [BSA] involvement ≥10%) for at least 6 months and had psoriasis that was considered inappropriate (based on severity or extent of affected area) for topical therapy, or their psoriasis was not adequately controlled by topical therapy in spite of at least 4 weeks of prior treatment (or per label) with at least one topical therapy for psoriasis. Patients previously treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy (conventional or biologic), including treatment failures, were permitted to enroll.

The main exclusion criteria were: clinically significant cardiac, endocrinological, pulmonary, neurological, psychiatric, hepatic, renal, hematological or immunological disease; prior medical history of suicide attempt at any time in the patient's lifetime before screening or randomization, or major psychiatric illness requiring hospitalization within the last 3 years; other major uncontrolled disease; significant infection; active tuberculosis (TB) or a history of incompletely treated TB; prolonged sun or ultraviolet exposure; or use of biologics within 12–24 weeks, conventional systemic treatments or phototherapy within 4 weeks, or active topical treatments for psoriasis within 2 weeks of randomization. Low‐potency (weak) topical corticosteroids were allowed as background therapy for face, axillae and groin psoriasis lesions only; salicylic acid preparations for scalp lesions and unmedicated skin moisturizers for body lesions were also permitted, except within 24 h before each study visit.

Study assessments

The primary efficacy end‐point was the proportion of patients achieving a 75% or more reduction from baseline in PASI score (PASI‐75) at week 16.15 The first secondary efficacy end‐point was the proportion of patients achieving static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) at week 16 in patients with an sPGA score of 3 or more (moderate or greater) at baseline. A 6‐point sPGA was used with a scale ranging from 0 (clear, except for residual discoloration) to 5 (severe; majority of lesions have individual scores for thickness, erythema and scaling that average 5).16 Additional efficacy end‐points assessed included mean percentage change from baseline in the affected BSA, mean percentage change from baseline in PASI score, percentage of patients achieving PASI‐50, percentage of patients achieving a 90% or more reduction from baseline in PASI score (PASI‐90), mean change from baseline in pruritus visual analog scale (VAS) score (mm) and mean change from baseline in the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) total score. The severity of patient‐reported pruritus was measured using a 100‐mm VAS, which has been shown to be a valid and reliable method for pruritus assessment in patients with psoriasis.17, 18 Patients rated the severity of their pruritus in the past week on a scale ranging 0 mm (no itch at all) to 100 mm (worst itch imaginable). Quality of life (QoL) was assessed using the DLQI, a validated 10‐item questionnaire commonly used in psoriasis clinical studies to evaluate health‐related patient QoL.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The DLQI scores range from 0 (no impairment) to 30 (worst QoL).

Safety evaluations, including collection of AEs, vital signs, laboratory evaluations, physical examinations, electrocardiograms and chest radiographs, were performed.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy and safety assessments were conducted for the modified intent‐to‐treat (mITT) population, which included all patients who were randomized and received at least one dose of study medication; patients not dispensed study medication were excluded from the mITT population. Approximately 246 patients were planned to provide more than 90% power to detect a 20% difference between apremilast and placebo in PASI‐75 response, as well as a sufficient database for safety evaluations. To control the overall type 1 error rate with multiple group and end‐point comparisons, statistical testing was performed in a hierarchical fashion; end‐points were analyzed in sequence only if for the previous end‐point a statistically significant difference was detected between apremilast and placebo. Within each end‐point, a Hochberg procedure was applied to control the multiple comparisons between the two active doses versus placebo.

The PASI‐75 response and other discrete variables were analyzed using a two‐sided χ2‐test at the 0.05 significance level; continuous variables were analyzed using an analysis of covariance model with treatment as factor and baseline value as covariate. For the primary analysis of PASI‐75, missing values were accounted for using the last observation carried forward methodology; multiple sensitivity analyses (including non‐responder imputation [NRI]) were conducted for the primary end‐point (PASI‐75 at week 16) and selected secondary end‐points (PASI‐50, PASI‐90 and sPGA score of 0 [clear] or 1 [minimal] at week 16).

Results

Patients

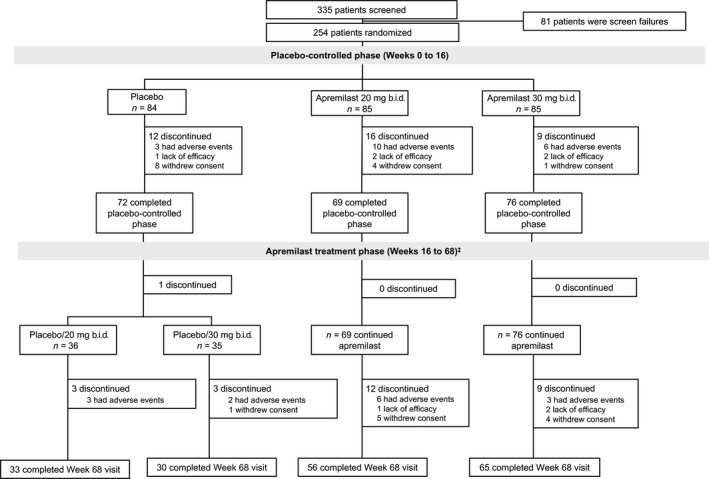

In total, 254 patients were randomized, received at least one dose of study medication, and were included in the mITT and safety populations. Of the 254 patients who were randomized, 217 (85.4%) completed the study visit at week 16; 216 patients entered the apremilast treatment phase and 184 (85.2%) completed the study evaluation at week 68 (Fig. 2). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were generally balanced between groups (Table 1). Most patients were male (79.5%); mean age was 50.8 years, mean weight 69.93 kg, mean psoriasis duration 12.95 years, mean PASI score 21.20 and mean psoriasis‐involved BSA 30.3%.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition through week 68. ‡An additional five patients (two placebo/apremilast 30 mg b.i.d., one apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. and two apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.) who completed week 40 were not included in “patients who completed the apremilast treatment phase at week 68” because of missing principal investigator signature on the treatment disposition case report form. These patients were discontinued from treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics

| Placebo n = 84 | Apremilast | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 mg b.i.d. n = 85 | 30 mg b.i.d. n = 85 | ||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 48.3 (12.0) | 52.2 (12.5) | 51.7 (12.7) |

| Male, n (%) | 62 (73.8) | 69 (81.2) | 71 (83.5) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 24.7 (4.7) | 25.8 (4.2) | 24.9 (3.7) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 68.5 (13.8) | 71.2 (12.9) | 70.1 (13.0) |

| Duration of psoriasis, mean (SD), years | 12.4 (9.4) | 12.6 (10.6) | 13.9 (9.2) |

| PASI score (0–72), mean (SD) | 19.9 (8.9) | 22.1 (9.6) | 21.6 (8.9) |

| PASI score >20, n (%) | 28 (33.3) | 41 (48.2) | 38 (44.7) |

| BSA, mean (SD), % | 28.0 (15.4) | 32.0 (17.5) | 30.7 (16.1) |

| BSA >20%, n (%) | 51 (60.7) | 54 (63.5) | 58 (68.2) |

| sPGA = 3 (moderate), n (%) | 49 (58.3) | 46 (54.1) | 40 (47.1) |

| sPGA = 4 (marked), n (%) | 15 (17.9) | 24 (28.2) | 25 (29.4) |

| sPGA = 5 (severe), n (%) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 6 (7.1) |

| DLQI score (0–30), mean (SD) | 7.5 (5.3) | 7.4 (5.6) | 7.4 (5.7) |

| Pruritus VAS (0–100 mm), mean (SD) | 57.1 (26.7) | 49.9 (26.6) | 53.1 (28.6) |

| Prior use of biologic therapy, n (%) | 4 (4.8) | 3 (3.5) | 2 (2.4) |

| Prior use of conventional systemic medications, n (%) | 22 (26.2) | 34 (40.0) | 26 (30.6) |

The n reflects the number of randomized patients; actual number of patients available for each parameter may vary. BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; sPGA, static Physician Global Assessment; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analog scale.

Efficacy

Placebo‐controlled period

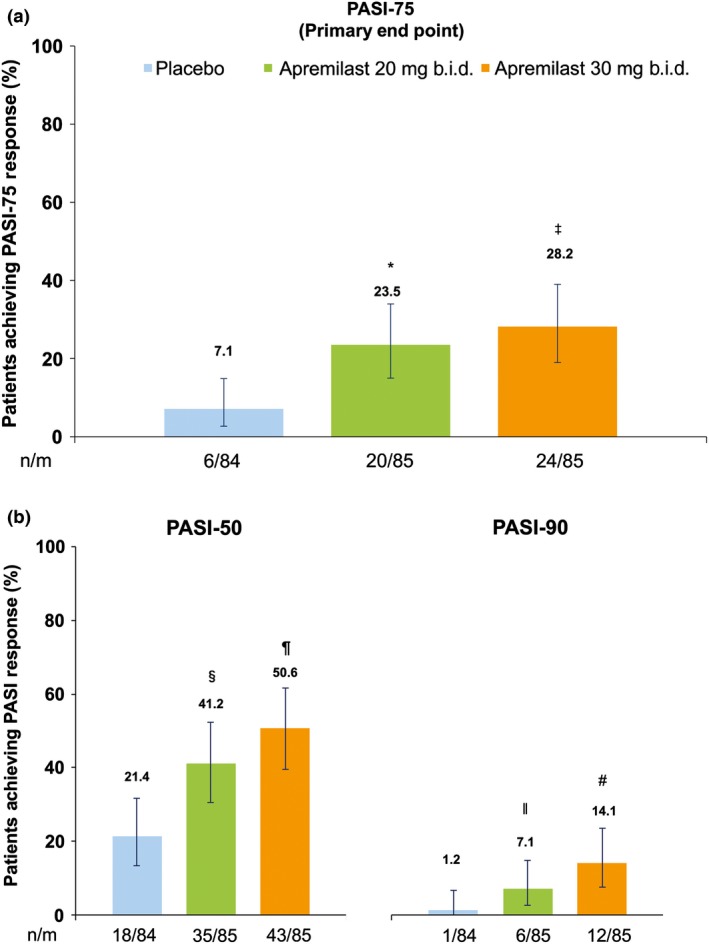

At week 16, significantly greater proportions of patients receiving apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. (23.5% [20/85]) and apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. (28.2% [24/85]) achieved a PASI‐75 response (primary end‐point) compared with patients receiving placebo (7.1% [6/84]) (P = 0.0032 apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. vs placebo; P = 0.0003 apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. vs placebo) (Fig. 3a; Table 2). Significantly greater proportions of apremilast‐treated patients with a baseline sPGA score of 3 or more (moderate or greater) had an sPGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) at week 16 (20 mg b.i.d., 23.9% [17/71]; 30 mg b.i.d., 29.6% [21/71]) compared with placebo (8.8% [6/68]) (P = 0.0165 apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. vs placebo; P = 0.0020 apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. vs placebo) (Table 2). Results of the NRI sensitivity analyses for these end‐points were consistent with those of the primary analysis (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Proportions of patients who achieved (a) PASI‐75 and (b) PASI‐50 and PASI‐90 at week 16. n/m = number of responders/number of patients in the mITT population; missing data were handled using LOCF methodology. *P = 0.0032 apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. versus placebo. ‡ P = 0.0003 apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. versus placebo. § P = 0.0057 apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. vs placebo. ¶ P < 0.0001 apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. versus placebo. ׀׀ P = 0.0556 apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. versus placebo. # P = 0.0016 apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. versus placebo. LOCF, last observation carried forward; mITT, modified intent‐to‐treat; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PASI‐50, ≥50% reduction from baseline in PASI score; PASI‐75, ≥75% reduction from baseline in PASI score; PASI‐90, ≥90% reduction from baseline in PASI score.

Table 2.

Efficacy assessments at week 16 (mITT) and week 68

| Placebo‐controlled period (week 16) | Apremilast treatment phase (weeks 16 to 68) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo n = 84 | Apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. n = 85 | Apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. n = 85 | Placebo/Apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. n = 36 | Placebo/Apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. n = 35 | Apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. n = 85 | Apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. n = 85 | |

| Primary end‐point | |||||||

| PASI‐75 (LOCF), n (%) | 6 (7.1) | 20 (23.5)‡ | 24 (28.2)† | 20 (55.6) | 20 (57.1) | 28 (32.9) | 35 (41.2) |

| PASI‐75 (NRI), n (%) | 6 (7.1) | 19 (22.4)§ | 24 (28.2)† | 20 (55.6) | 19 (54.3) | 26 (30.6) | 35 (41.2) |

| Other efficacy end‐points | |||||||

| sPGA score 0 or 1 (LOCF), n (%)¶ | 6 (8.8) | 17 (23.9)§ | 21 (29.6)‡ | 13 (44.8) | 16 (59.3) | 28 (39.4) | 28 (39.4) |

| sPGA score 0 or 1 (NRI), n (%)¶ | 6 (8.8) | 17 (23.9)§ | 19 (26.8)§ | 13 (44.8) | 15 (55.6) | 26 (36.6) | 28 (39.4) |

| Percentage change in psoriasis affected BSA, mean (SD)‡,** | 8.1 (58.2) | −22.0 (46.3)† | −30.6 (47.1)* | −60.8 (32.0) | −49.8 (62.2) | −53.4 (34.4) | −58.8 (30.9) |

| Percentage change in PASI score from baseline, mean (SD)** | −3.6 (59.0) | −33.2 (48.5)† | −43.2 (43.1)* | −70.3 (26.1) | −62.6 (42.8) | −62.9 (29.4) | −66.2 (26.1) |

| PASI‐50 (LOCF), n (%) | 18 (21.4) | 35 (41.2)§ | 43 (50.6)* | 31 (86.1) | 28 (80.0) | 55 (64.7) | 60 (70.6) |

| PASI‐50 (NRI), n (%) | 18 (21.4) | 32 (37.6)§ | 41 (48.2)† | 30 (83.3) | 26 (74.3) | 51 (60.0) | 57 (67.1) |

| PASI‐90 (LOCF), n (%) | 1 (1.2) | 6 (7.1) | 12 (14.1)‡ | 9 (25.0) | 9 (25.7) | 8 (9.4) | 9 (10.6) |

| PASI‐90 (NRI), n (%) | 1 (1.2) | 6 (7.1) | 12 (14.1) | 9 (25.0) | 9 (25.7) | 8 (9.4) | 9 (10.6) |

| Change in total DLQI score from baseline, mean (SD)** | +1.3 (5.7) | −0.4 (5.3)§ | −2.2 (5.0)* | −3.7 (7.3) | −1.9 (5.7) | −2.8 (4.6) | −3.3 (5.4) |

| Change in pruritus VAS score from baseline (mm) mean (SD)** | +4.8 (30.8) | −5.5 (29.3)† | −17.6 (32.0)* | −28.4 (38.7) | −18.5 (35.7) | −16.9 (32.1) | −25.6 (35.2) |

For categorical end‐points, week 16 missing data were handled with LOCF methodology; sensitivity analyses applied NRI methodology, where noted. *P < 0.0001; † P ≤ 0.0003; ‡ P ≤ 0.006; § P < 0.05 vs placebo, based on 2‐sided χ 2 test for categorical end‐points and two‐way analysis of covariance for continuous end‐points. ¶Among patients with sPGA ≥3 (moderate to severe) at baseline (placebo‐controlled period: placebo n = 68; apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. n = 71; apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. n = 71). Apremilast treatment period: placebo/apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. n = 29; placebo/apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. n = 27; apremilast 20 mg b.i.d./apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. n = 71; apremilast 30 mg b.i.d./apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. n = 71). **For continuous end‐points, missing values were accounted for using LOCF. BSA, psoriasis‐involved body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; LOCF, last observation carried forward; NRI, non‐responder imputation; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PASI‐50, ≥50% reduction from baseline in PASI score; PASI‐75, ≥75% reduction from baseline in PASI score; PASI‐90, ≥90% reduction from baseline in PASI score; sPGA, static Physician Global Assessment (0 = clear, 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = marked, 5 = severe); VAS, visual analog scale.

Significant improvements at week 16 with apremilast versus placebo were observed for other efficacy end‐points, including mean percentage change from baseline in affected BSA, mean percentage change from baseline in PASI score, proportion of patients who achieved PASI‐50, and mean change from baseline in pruritus VAS and DLQI scores (Table 2). At week 16, 41.2% (35/85) of patients receiving apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. and 50.6% (43/85) of patients receiving apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. achieved a PASI‐50 response compared with 21.4% (18/84) of those receiving placebo (P = 0.0057 vs apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.; P < 0.0001 vs apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.). Similarly, the percentage of patients achieving a PASI‐90 response at week 16 was higher among patients receiving apremilast (7.1% [6/85] 20 mg b.i.d.; 14.1% [12/85] 30 mg b.i.d.) than in those receiving placebo (1.2% [1/84], P = 0.0556 vs apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.; P = 0.0016 vs apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.) (Fig. 3b; Table 2). The mean percentage change from baseline in PASI score at week 16 was greater with apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. (−33.2%) and apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. (−43.2%) compared with placebo (−3.6%; P = 0.0002 vs apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. and P < 0.0001 vs apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.). Improvements in patient‐reported pruritus VAS scores (mean change from baseline) were observed as early as week 2 with non‐overlapping confidence intervals for the apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. group relative to the placebo group. Mean pruritus VAS scores at baseline were 57.1 mm (placebo), 49.9 mm (apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.) and 53.1 mm (apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.). At week 16, changes from baseline in patient‐reported pruritus VAS scores were 4.8 mm with placebo versus −5.5 mm with apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. (an ~11% decrease; P = 0.0003) and −17.6 mm with apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. (an ~33% decrease; P < 0.0001; Table 2). Mean DLQI scores were comparable across all groups at baseline (7.5 for placebo and 7.4 for both apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. and apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.). Statistically significant improvements in mean change from baseline in DLQI score were seen at week 16 with apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. (−0.4) and apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. (−2.2) versus placebo (1.3; P = 0.0204 vs apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.; P < 0.0001 vs apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.).

Apremilast treatment phase

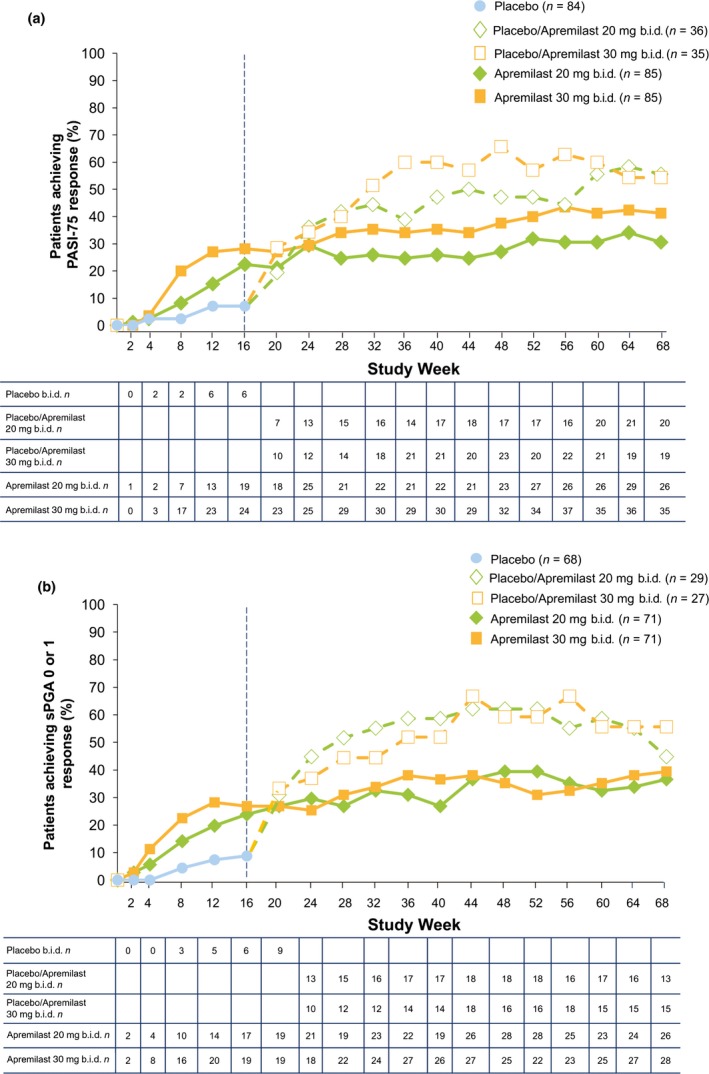

The PASI‐75 and sPGA 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) response rates were sustained in patients randomized to apremilast at baseline who continued treatment through week 68 (Fig. 4). At week 68, PASI‐75 response was achieved in 32.9% of patients in the apremilast 20 mg b.i.d./apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. group and 41.2% in the apremilast 30 mg b.i.d./apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. group. An sPGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) was achieved by 39.4% of patients with an sPGA score of 3 or more (moderate or greater) in both the apremilast 20 mg b.i.d./apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. and apremilast 30 mg b.i.d./apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. groups. Improvements were also observed among patients initially randomized to placebo at baseline who switched to apremilast at week 16 (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Proportions of patients who achieved (a) PASI‐75 and (b) sPGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) in patients with sPGA score of ≥3 (moderate or greater) at baseline over 68 weeks. n = number of responders in the mITT population; missing data were handled using non‐responder imputation. NRI, non‐responder imputation; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PASI‐75, ≥75% reduction from baseline in PASI score; sPGA, static Physician Global Assessment.

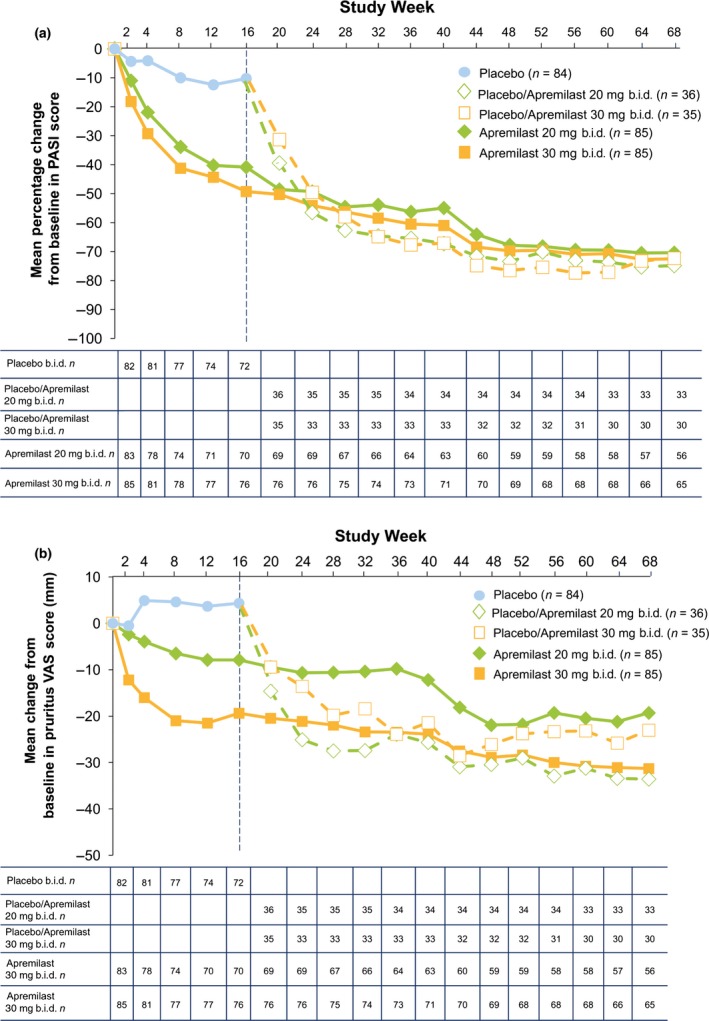

As illustrated in Figure 5, improvements in mean PASI score were sustained over 68 weeks of continued treatment. Mean percentage change from baseline in PASI score at week 68 was generally similar among all treatment groups, and ranged from −62.6% to −70.3% (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

(a) Mean percentage change from baseline in PASI score and (b) mean change from baseline in pruritus VAS score (mm) (b) over 68 weeks. Includes patients in the mITT population with sufficient data for evaluation at each time point, with no imputation for missing values; data are as observed. Mean (standard deviation) pruritus VAS scores (mm) at baseline were placebo, 57.1 (26.7); apremilast 20 mg b.i.d., 49.9 (26.6); and apremilast 30 mg b.i.d., 53.1 (28.6). mITT, modified intent‐to‐treat; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; VAS, visual analog scale.

Similar sustained beneficial clinical effects were observed across other efficacy end‐points with longer term apremilast treatment through week 68 (Table 2). Improvements from baseline in pruritus severity among patients randomized to apremilast at baseline were also consistent over time (Fig. 5b). At week 68, mean change from baseline in pruritus VAS score was −16.9 mm (apremilast 20 mg b.i.d./apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.) and −25.6 mm (apremilast 30 mg b.i.d./apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.); placebo patients who switched to apremilast at week 16 had mean changes in pruritus VAS scores of −28.4 mm (placebo/apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.) and −18.5 mm (placebo/apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.).

Safety

Placebo‐controlled period

During the placebo‐controlled period (0–16 weeks), most AEs were mild and did not result in discontinuation of treatment. The proportions of patients reporting at least one AE were 57.6% and 51.8% in the apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. and 30 mg b.i.d. groups, respectively, and 41.7% in the placebo group (Table 3). The most common AEs (occurring in ≥5% of patients in any treatment group) were nasopharyngitis, diarrhea and abdominal discomfort (Table 3). The proportion of patients reporting serious AEs (SAEs) was low (placebo, 0.0%; apremilast 20 mg b.i.d., 4.7%; apremilast 30 mg b.i.d., 0.0%); SAEs of bacterial infection (n = 1), cerebral hemorrhage (n = 1), coronary artery stenosis (n = 1) and cholelithiasis (n = 1) were reported in the apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. group.

Table 3.

Adverse events and laboratory abnormalities during the placebo‐controlled period and the apremilast‐exposure period

| Patients | Placebo‐controlled period 0–16 weeks | Apremilast‐exposure period 0–68 weeks | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo n = 84 | EAIR/100 patient‐years | Apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. n = 85 | EAIR/100 patient‐years | Apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. n = 85 | EAIR/100 patient‐years | Apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. n = 121 | EAIR/100 patient‐years | Apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. n = 120 | EAIR/100 patient‐years | |

| Overview, n (%) | ||||||||||

| ≥1 AE | 35 (41.7) | 201.2 | 49 (57.6) | 340.1 | 44 (51.8) | 290.2 | 94 (77.7) | 182.4 | 89 (74.2) | 154.2 |

| ≥1 severe AE | 1 (1.2) | 4.3 | 4 (4.7) | 18.1 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 12 (9.9) | 10.4 | 2 (1.7) | 1.6 |

| ≥1 serious AE | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 4 (4.7) | 18.1 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 11 (9.1) | 9.6 | 2 (1.7) | 1.6 |

| AE leading to drug withdrawal | 4 (4.8) | 17.3 | 10 (11.8) | 44.8 | 6 (7.1) | 25.1 | 19 (15.7) | 16.1 | 10 (8.3) | 7.9 |

| AE leading to death‡ | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1 (0.8) | 0.8 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 |

| Reported by ≥5% of patients in any treatment group, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (8.3) | 31.5 | 10 (11.8) | 49.0 | 10 (11.8) | 45.4 | 28 (23.1) | 28.7 | 35 (29.2) | 34.7 |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1.2) | 4.3 | 7 (8.2) | 33.4 | 8 (9.4) | 36.1 | 10 (8.3) | 9.1 | 12 (10.0) | 10.2 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 1 (1.2) | 4.3 | 1 (1.2) | 4.5 | 6 (7.1) | 26.9 | 3 (2.5) | 2.6 | 8 (6.7) | 6.8 |

| Influenza | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 6 (5.0) | 5.2 | 3 (2.5) | 2.4 |

| Leading to discontinuation in >1 patient in any treatment group, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Diarrhea | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1 (1.2) | 4.5 | 1 (1.2) | 4.2 | 1 (0.8) | 0.8 | 2 (1.7) | 1.6 |

| Psoriasis | 2 (2.4) | 8.6 | 3 (3.5) | 13.4 | 4 (4.7) | 16.7 | 5 (4.1) | 4.2 | 5 (4.2) | 4.0 |

| Select marked laboratory abnormalities,§ n/m (%) | ||||||||||

| ALT >3 × ULN, U/L | 0/84 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/85 (1.2) | 4.2 | 1/121 (0.8) | 0.8 | 1/120 (0.8) | 0.8 |

| AST >3 × ULN, U/L | 0/84 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/85 (1.2) | 4.2 | 1/121 (0.8) | 0.8 | 1/120 (0.8) | 0.8 |

| Total bilirubin >1.8 × ULN, mg/dL | 1/84 (1.2) | 4.3 | 1/85 (1.2) | 4.5 | 2/85 (2.4) | 8.5 | 3/121 (2.5) | 2.6 | 2/120 (1.7) | 1.6 |

| Cholesterol >302 mg/dL | 1/84 (1.2) | 4.3 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 2/121 (1.7) | 1.7 | 1/120 (0.8) | 0.8 |

| Creatinine >1.7 × ULN, mg/dL | 0/84 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/121 (0.8) | 0.8 | 0/120 (0.0) | 0.0 |

| Hemoglobin A1c >9% | 2/84 (2.4) | 8.8 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 2/121 (1.7) | 1.7 | 1/120 (0.8) | 0.8 |

| Triglycerides >301 mg/dL | 15/84 (17.9) | 70.1 | 18/85 (21.2) | 92.8 | 21/85 (24.7) | 103.2 | 33/121 (27.3) | 35.7 | 41/120 (34.2) | 43.4 |

| Hemoglobin | ||||||||||

| Male <10.5 or female <8.5 g/dL | 1/84 (1.2) | 4.3 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 2/121 (1.7) | 1.7 | 1/120 (0.8) | 0.8 |

| Male >18.5 or female >17.0 g/dL | 0/84 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/121 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/120 (0.8) | 0.8 |

| Lymphocytes <800 μL | 2/84 (2.4) | 8.8 | 2/85 (2.4) | 8.9 | 3/85 (3.5) | 12.9 | 5/121 (4.1) | 4.3 | 7/120 (5.8) | 5.8 |

| Neutrophils <1000 μL | 0/84 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/121 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/120 (0.0) | 0.0 |

| Platelets | ||||||||||

| <7.5 × 104/μL | 0/84 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/121 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/120 (0.0) | 0.0 |

| >60 × 104/μL | 0/84 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/85 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/121 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/120 (0.0) | 0.0 |

The apremilast‐exposure period (weeks 0–68) included all patients who received apremilast, regardless of when treatment was initiated. Exposure‐adjusted incidence rate per 100 patient‐years is defined as 100 times the number (n) of patients reporting the event divided by patient‐years within the phase (up to the first event start date for patients reporting the event). The n/m represents patients with ≥1 occurrence of the abnormality (n)/patients with ≥1 post‐baseline value (m). §All laboratory measurements are non‐fasting values. ‡One death was reported during the study in a 52‐year‐old man with 34 years of smoking history and receiving apremilast 20 b.i.d. On study day 197, the patient was diagnosed with severe metastatic lung cancer with contralateral pulmonary, lymph node and brain metastases. He died on study day 254 due to this event. Investigational product was permanently withdrawn due to this event and the patient's last dose of apremilast was study day 197. AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; EAIR, exposure‐adjusted incidence rate; ULN, upper limit of normal.

During the placebo‐controlled period, no patients in the placebo group or the apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. group experienced cardiac events; three cardiac events were experienced by patients receiving apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.: coronary artery stenosis (n = 1, considered severe), left ventricular hypertrophy (n = 1, mild) and extrasystoles (n = 1, mild). There were no AEs of depression, suicidal ideation, or attempted or completed suicide during the placebo‐controlled period (0–16 weeks); one patient with prior history of anxiety disorder and insomnia receiving apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. during the placebo‐controlled period discontinued treatment due to anxiety disorder.

Safety through 68 weeks

The most common AEs reported through 68 weeks were nasopharyngitis, diarrhea, abdominal discomfort and influenza (Table 3). In general, rates of AEs leading to withdrawal of study medication were low and similar to those reported during the placebo‐controlled period (Table 3). Rates and exposure‐adjusted incidence rates/100 patient‐years of severe AEs, SAEs, and AEs that led to withdrawal remained generally low, but appeared to be somewhat higher in patients who received apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. than in those who received apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. (Table 3). The only AEs that led to discontinuation in more than one patient during the 0–68‐week apremilast‐exposure period were diarrhea (overall, n = 3 [1.2%]) and psoriasis (overall, n = 10 [4.1%]). No cases of tuberculosis (de novo or reactivation) were reported for the 68‐week period.

During the 0–68‐week apremilast‐exposure period, three patients experienced a cardiac event, including congestive cardiac failure (n = 2, one each receiving apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. [severe] and apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. [moderate]) and atrial flutter (apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. [mild]). The one patient (apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.) who experienced ventricular hypertrophy during the placebo‐controlled period also experienced atrial fibrillation (moderate) during the apremilast‐exposure period.

The incidence of marked laboratory abnormalities for hematology and clinical chemistry parameters was generally low and comparable between treatment groups, and exhibited no patterns or changes with continued apremilast exposure over 68 weeks; for both analysis periods, mean changes from baseline in these parameters were not clinically meaningful.

During the placebo‐controlled period, mean/median change in weight from baseline to the last value measured was −0.20/0.00 kg (placebo), −0.56/−0.20 kg (apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.) and −0.86/−0.70 kg (apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.). During the 68‐week apremilast‐exposure period, mean/median change in weight from baseline to the last value measured was −0.65/−0.50 kg (apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.) and −1.16/−1.05 kg (apremilast 30 mg b.i.d.). Most patients maintained their weight within ±5% of baseline weight; at the end of the 68‐week apremilast‐exposure period, weight loss of more than 5% was reported in 11.6% (14/121) of patients receiving apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. and 14.2% (17/120) of patients receiving apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. There were no overt clinical consequences that occurred in those patients who had weight loss of more than 5%. During the placebo‐controlled period, no patient in any treatment group experienced more than 20% weight loss.

Discussion

This phase 2b randomized, placebo‐controlled study in Japanese patients demonstrated that oral apremilast treatment yields statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, compared with placebo. The primary end‐point, PASI‐75 response at week 16, was met with significantly greater PASI‐75 response rates achieved in patients receiving apremilast 20 mg b.i.d. or 30 mg b.i.d. than in those receiving placebo. Improvements in psoriasis symptoms at week 16 with apremilast treatment, based on PASI‐75 response rates and other secondary efficacy end‐points, were sustained over 68 weeks with continued apremilast treatment. Therapeutic effects were generally greater in magnitude with apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. compared with apremilast 20 mg b.i.d., with no evidence of an increase in safety risks or tolerability burden. PASI‐75 response also increased among patients initially randomized to placebo who switched to apremilast at week 16; the higher response observed among these patients compared with those initially randomized to apremilast may have been due to greater variability resulting from the small numbers of patients in each group (placebo/apremilast 20 mg b.i.d., n = 36; placebo/apremilast 30 mg b.i.d., n = 36). In addition, placebo patients who were not re‐randomized at week 16 (n = 13) were not included in the calculation of response of the placebo/apremilast groups.

This is the first randomized controlled trial of apremilast to be conducted in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. In general, the overall efficacy findings are consistent with those reported in phase 2 and 3 studies.10, 11, 12 The phase 3 Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis (ESTEEM) clinical trial program investigating apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. demonstrated that this dose is effective, has an acceptable safety profile and is generally well tolerated in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis for up to 52 weeks.11, 12 Differences in demographics and comorbidities, however, may contribute to differences observed in efficacy for each patient population. The Japanese patient population enrolled in the current study differs from the ESTEEM patient population across several key demographic and clinical disease characteristics, in line with previous epidemiological and clinical studies in patients with psoriasis in Japan and other Asian countries.2 In contrast to ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2, the current study included a greater proportion of males (~80% vs ~68% in ESTEEM 1 and ~67% in ESTEEM 2). Patients in the current study also had a lower average body mass index (~25.1 kg/m2 vs ~31.0 kg/m2 in ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2) and more extensive skin involvement (BSA >20%: ~64.2% vs ~57.5 in ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2). In addition, far fewer patients in the current study had received prior biologic therapy as compared with the ESTEEM patient population (3.5% vs ~30% in ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2). At baseline, the enrolled Japanese patients in the current study had less severe symptoms (e.g. pruritus VAS score ~53 mm vs ~66 mm in ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2) and reported less impairment in QoL, based on lower average baseline DLQI scores (~7 vs ~12 in ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2).11, 12 Regardless of such differences, the nature and magnitude of the therapeutic effect on PASI and sPGA responses with oral apremilast were generally similar to those observed in the ESTEEM studies.11, 12

The safety profile of apremilast did not raise any new safety signals, and rates of AEs, SAEs and discontinuations were similar to those previously reported with apremilast from randomized phase 3 studies in psoriasis11, 12 and psoriatic arthritis.13, 14 In line with these prior studies, most AEs were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to discontinuation. No pattern of increased risk of major adverse cardiac events, malignancies or serious infections was observed with apremilast treatment versus placebo. The relatively small numbers of these events occurred primarily among patients receiving apremilast 20 mg b.i.d.; by contrast, few such events were seen with the higher apremilast 30 mg b.i.d. dose. Changes in clinical laboratory parameters were not clinically meaningful, and marked abnormalities were transient and showed no treatment‐related pattern. Weight loss was observed with apremilast treatment, as has been reported previously.11, 12 The average changes in weight at the end of the apremilast exposure period (0–68 weeks) were relatively small, and the majority of current patients maintained their weight within ±5% of baseline. Among patients with weight loss of more than 5%, there were no overt clinical consequences.

Systemic treatment options for Japanese patients with moderate to severe psoriasis include oral treatments such as cyclosporin and etretinate, and the injectable biologic agents adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, secukinumab, brodalumab and ixekizumab.24 Although these therapies have demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials, the long‐term use of systemic therapies is often limited by safety considerations (e.g. risk of infection and malignancy, nephrotoxicity after chronic administration of cyclosporin, teratogenicity risk by etretinate, the development of neutralizing antibodies and/or potential reactivation of tuberculosis with immunosuppressive biologic therapy). Phototherapy may also be inconvenient for patients due to the requirement for frequent visits or hospitalization in the clinical setting in Japan. In addition, because the introduction of biologics in Japan is restricted to Japanese Dermatological Association (JDA) board‐approved core hospitals that have at least one full‐time JDA board‐certified dermatologist on staff, most community dermatologists are not allowed to initiate biologic therapy by themselves for psoriasis patients who visit their clinics regularly.

Taking these factors in Japan into consideration, despite recent advances in psoriasis treatment, there remains an unmet need in the community dermatology setting for more convenient, effective systemic treatments that offer sustained efficacy and manageable long‐term safety. Apremilast represents a novel small‐molecule, oral therapeutic option for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis that is effective and demonstrates an acceptable tolerability profile, with no requirement for routine laboratory monitoring. As such, it may help to fill a significant treatment gap for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis that is inappropriate for or not adequately controlled with topical therapy and requires systemic therapy. Beyond the reduction in clinical disease severity that has been well documented with apremilast treatment, its oral route of administration and comparatively high level of long‐term safety and tolerability may address patient desires for convenience and low risk.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that apremilast was efficacious and generally well tolerated in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Apremilast demonstrated significant improvements in symptoms of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis over 16 weeks, and these improvements were sustained through week 68 across a range of end‐points, including patient‐reported outcomes, that contribute significantly to patients’ disease severity and QoL. Apremilast demonstrated an acceptable safety profile with no need for extensive laboratory monitoring. The results of this study suggest that apremilast is an effective oral therapeutic option for treatment of Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Conflict of Interest

Mamitaro Ohtsuki reports consultancy and speaker fees. Yukari Okubo reports consultancy fees. Shinichi Imafuku reports research funds, consultancy fees and speaker fees. Robert M. Day, Peng Chen, Rosemary Petric and Allan Maroli report stock or shares in Celgene Corporation and/or employment by Celgene Corporation. Osamu Nemoto has no relevant financial or personal relationships and no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors received editorial support in the preparation of the manuscript from Kathy Covino, Ph.D., of Peloton Advantage, LLC, funded by Celgene Corporation. This study was funded by Celgene Corporation.

References

- 1. Lowes MA, Suarez‐Farinas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol 2014; 32: 227–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T et al Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open 2015; 5 (1): e006450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsu S, Papp KA, Lebwohl MG et al Consensus guidelines for the management of plaque psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 2012; 148: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J et al Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population‐based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70: 871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schafer PH, Parton A, Gandhi AK et al Apremilast, a cAMP phosphodiesterase‐4 inhibitor, demonstrates anti‐inflammatory activity in vitro and in a model of psoriasis. Br J Pharmacol 2010; 159: 842–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schafer PH, Parton A, Capone L et al Apremilast is a selective PDE4 inhibitor with regulatory effects on innate immunity. Cell Signal 2014; 26: 2016–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schett G, Sloan VS, Stevens RM, Schafer P. Apremilast: a novel PDE4 inhibitor in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2010; 2: 271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gottlieb AB, Strober B, Krueger JG et al An open‐label, single‐arm pilot study in patients with severe plaque‐type psoriasis treated with an oral anti‐inflammatory agent, apremilast. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 1529–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Papp K, Cather JC, Rosoph L et al Efficacy of apremilast in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL et al Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM 1]). J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73: 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paul C, Cather J, Gooderham M et al Efficacy and safety of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis over 52 weeks: a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (ESTEEM 2). Br J Dermatol 2015; 173: 1387–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez‐Reino JJ et al Longterm (52‐week) results of a phase III randomized, controlled trial of apremilast in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2015; 42: 479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edwards CJ, Blanco FJ, Crowley J et al Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with psoriatic arthritis and current skin involvement: a phase III, randomised, controlled trial (PALACE 3). Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 1065–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis–oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica 1978; 157: 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leonardi CL, Powers JL, Matheson RT et al Etanercept as monotherapy in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2014–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reich A, Heisig M, Phan NQ et al Visual analogue scale: evaluation of the instrument for the assessment of pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92: 497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phan NQ, Blome C, Fritz F et al Assessment of pruritus intensity: prospective study on validity and reliability of the visual analogue scale, numerical rating scale and verbal rating scale in 471 patients with chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92: 502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125: 659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, Sturkey R, Finlay AY. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology 2015; 230: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994–2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 997–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bronsard V, Paul C, Prey S et al What are the best outcome measures for assessing quality of life in plaque type psoriasis? A systematic review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24 (Suppl 2): 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohtsuki M, Terui T, Ozawa A et al Japanese guidance for use of biologics for psoriasis (the 2013 version). J Dermatol 2013; 40: 683–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]