Abstract

Background

Surgical task‐sharing may be central to expanding the provision of surgical care in low‐resource settings. The aims of this paper were to describe the set‐up of a new surgical task‐sharing training programme for associate clinicians and junior doctors in Sierra Leone, assess its productivity and safety, and estimate its future role in contributing to surgical volume.

Methods

This prospective observational study from a consortium of 16 hospitals evaluated crude in‐hospital mortality over 5 years and productivity of operations performed during and after completion of a 3‐year surgical training programme.

Results

Some 48 trainees and nine graduated surgical assistant community health officers (SACHOs) participated in 27 216 supervised operations between January 2011 and July 2016. During training, trainees attended a median of 822 operations. SACHOs performed a median of 173 operations annually. Caesarean section, hernia repair and laparotomy were the most common procedures during and after training. Crude in‐hospital mortality rates after caesarean sections and laparotomies were 0·7 per cent (13 of 1915) and 4·3 per cent (7 of 164) respectively for operations performed by trainees, and 0·4 per cent (5 of 1169) and 8·0 per cent (11 of 137) for those carried out by SACHOs. Adjusted for patient sex, surgical procedure, urgency and hospital, mortality was lower for operations performed by trainees (OR 0·47, 95 per cent c.i. 0·32 to 0·71; P < 0·001) and SACHOs (OR 0·16, 0·07 to 0·41; P < 0·001) compared with those conducted by trainers and supervisors.

Conclusion

SACHOs rapidly and safely achieved substantial increases in surgical volume in Sierra Leone.

Short abstract

Benchmark analysis

Introduction

One of the significant barriers to expansion of surgical care in low‐income countries is a shortage of human resources1. Task‐sharing is defined as a rational redistribution of tasks among healthcare workers to maximize the efforts of the existing workforce2, and is recommended by the WHO for several tasks, including certain surgical procedures3. Expanding the surgical workforce in low‐resource settings by task‐sharing has been found to be cost‐ and time‐effective4, 5, 6 without corrupting surgical outcomes7, 8. In addition, it probably improves retention of the workforce at the district level9. Although task‐sharing in surgery is applied commonly in several East and Central African countries10, 11, it has not been adopted to the same extent in West Africa12. The 2015 World Health Assembly13 resolution aiming to strengthen emergency and essential surgical care worldwide urges member states to make: ‘…more effective use of the health care workforce through task‐sharing…’. Although task‐sharing in surgery has been widely debated and described in key publications in recent years1, 4, there are limited data on the safety of surgical task‐sharing programmes and the productivity of associate clinicians as surgical providers.

Sub‐Saharan West Africa has the highest unmet surgical needs in the world4. Before the Ebola outbreak, there were ten specialist surgical providers in government (public) hospitals14 and 26 in private non‐profit hospitals15 in Sierra Leone. This corresponds to less than 5 per cent of the minimum threshold of 20 specialist surgeons, obstetricians and anaesthetists per 100 000 population, recently recommended by the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery4. To address the shortage of surgical providers, the Sierra Leonean Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS) and the non‐profit organization CapaCare initiated a surgical task‐sharing training programme in 2011. The implementation strategy was to improve access to emergency surgical care among rural populations by enabling non‐specialized medical doctors (MDs) and associate clinicians to manage surgical and obstetric emergencies safely. A surgical training programme (STP) was developed that made optimal use of the limited surgical trainers available in the country. The goal was to train 60 associate clinicians and junior MDs by 2021, such that they could deliver surgical services safely in government district hospitals and be as productive as the existing surgical workforce. Five years after initiation of this programme, the aim of the present article was to describe the set‐up of the STP, assess productivity and safety, and estimate its future role in contributing to surgical volume in Sierra Leone.

Methods

Surgical training programme

The STP was planned in 2009 as Sierra Leone was recovering from a devastating civil war. This country, with 5·5 million inhabitants, at that time had only 167 MDs in clinical practice16, poor output from the medical school and no formal postgraduate training available in surgery or obstetrics14. Surgical care was not prioritized in the national health agenda17, despite an extensive surgical disease burden and mortality18, and there was more than 90 per cent unmet surgical need19. In rural areas, where the majority of the population resides, 30‐fold fewer operations were performed compared with urban areas15.

The STP is located principally at district hospitals to promote post‐training retention in the provinces and avoid diverting resources from any informal training of MDs in the main teaching hospitals in the capital, Freetown. The curriculum is based on the WHO Integrated Management for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care tool kit, developed by the Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care20. The training lasts 3 years and the graduates are meant to be absorbed by the MoHS and posted to district government hospitals on completion of training.

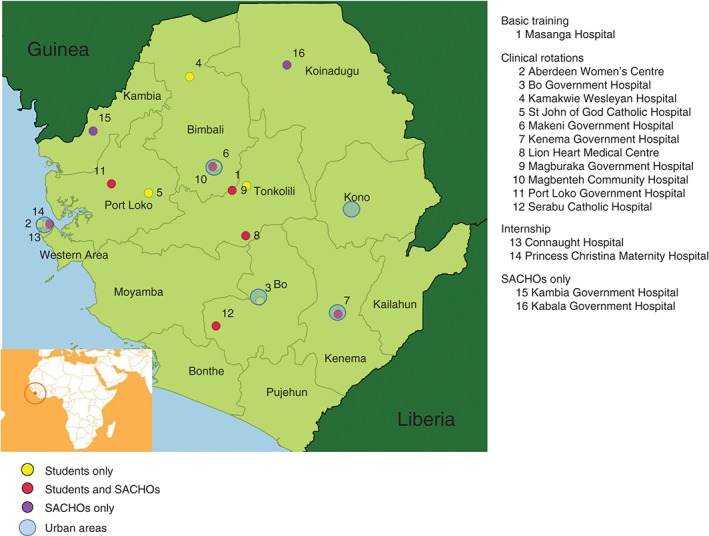

Trainers and training sites were identified by visiting and assessing the surgical activity and infrastructure of all provincial hospitals with 24‐h availability of MDs performing surgery19. The most surgically active were invited to take part as partner hospitals and a memorandum of understanding granted trainees supervised access to all surgical and obstetric care (Appendix S1, supporting information). Initially, all partner hospitals were run by private non‐profit organizations, based on limited capacity and personnel in government district hospitals. Several government hospitals subsequently became partners (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Hospitals as of July 2016 taking part in the surgical training programme or that have employed surgical assistant community health officers (SACHOs)

All associate clinicians (known as community health officers (CHOs) in Sierra Leone) and junior MDs who meet the minimum entry criteria are eligible for the STP. CHOs have 3‐year basic medical diploma training to be in charge of community health centres21, but many also work as medical operatives in hospitals. CHOs must complete 2 years of postgraduate clinical practice before applying for the STP. MDs can apply directly after internship. Applicants are interviewed by CapaCare and the MoHS; a more rigorous full‐day assessment was added in 2014. Positive discrimination favours women and applicants from highly underserved districts among equally qualified candidates. Trainee salaries are paid by the MoHS or CapaCare. There are no tuition fees, but a 4‐year postgraduate binding agreement with the MoHS has been introduced to promote retention in public service. Two trainees began in January 2011 and, since then, between four and seven have been admitted biannually.

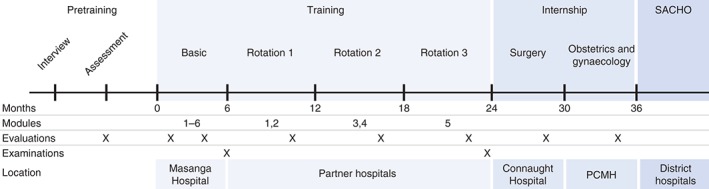

Fig. 2 outlines the training content and time frame. For 6 months, trainees undergo an introductory course at the central teaching facility, Masanga Hospital in Tonkolili district22. The theoretical training has evolved and matured over the past 5 years, and now comprises six intensive modules lasting 2–4 weeks (Appendix S2, supporting information). These modules are taught by teams of one to three international trainers, who are all specialists in surgery, obstetrics, anaesthesia, orthopaedics and radiology, in addition to midwives, and anaesthesia and operating theatre nurses. Local specialist surgeons provide theoretical and practical training during shorter courses (2–3 days). Training encompasses predefined or problem‐based lectures, e‐learning, grand rounds, case presentations, journal clubs, mortality and morbidity reviews, bedside clinical teaching, outpatient clinics, radiology conferences, basic ultrasound training, surgical audits, surgical skills laboratories, veterinary laboratories for emergency and trauma procedures, and hands‐on operative training to master context‐adapted and resource‐poor surgery.

Figure 2.

Content and time frame for the surgical training programme. SACHO, surgical assistant community health officer; PCMH, Princess Christina Maternity Hospital

After successful completion of the introductory course, trainees undergo three 6‐month clinical rotations in partner hospitals, engaging in all aspects of care of the surgical patient. Trainees are assigned to a local supervisor, a MD or specialist in surgery and/or obstetrics. At specific intervals (Appendix S2, supporting information), they are called back to Masanga Hospital for refresher training. A monitoring and evaluation officer, and national and international training coordinators supervise trainees and trainers at all training sites.

Trainee progression is gauged by informal guidance, formal written evaluations, biannual review of surgical logbooks, and written and oral examinations. Local specialist surgeons and obstetricians, all faculty at the College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences of the University of Sierra Leone, assess the results of the final written and oral examinations after 2 years. A successful outcome grants a diploma in Emergency Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The MDs are then posted to a government hospital. CHOs complete a 1‐year internship in the main tertiary surgical and maternity training hospitals in Freetown, which, if completed satisfactorily, leads to appointment as a surgical assistant community health officer (SACHO) at a government district hospital. All operations performed by trainees and SACHOs require the supervision of a MD.

Data collection

A prospective observational registry began with the initiation of the STP. Data were obtained from trainees' and SACHOs' surgical logbooks. Twenty items related to patient demographics, operation, surgical provider, hospital and outcomes were recorded for all operations between January 2011 and July 2016 (Appendix S3, supporting information).

Logbook recording of roles during an operation builds upon the supervision definitions approved by the Joint Committee on Surgical Training (JCST) in the UK and Ireland23. Observed is a procedure observed by an unscrubbed trainee. Assisted is where a trainer performs the key components of a procedure. Directly supervised (JCST category S‐TS) is when the trainee performs key components of the procedure with the trainer scrubbed. Indirectly supervised (JCST category S‐TU and P) is when the trainee completes the procedure from start to finish and the trainer is unscrubbed. Paper logbooks were signed and validated by trainers after each procedure and uploaded monthly (Microsoft® Excel format; Microsoft, Redmond, Washington USA) to a cloud server for review.

Crude in‐hospital mortality, the most commonly used definition of perioperative risk in low‐resource settings24, was used as a pragmatic marker of safety. Mortality rates following trainees' and SACHOs' indirectly supervised operations were compared with previously documented mortality from Sierra Leone25, 26. In addition, mortality associated with the operations performed under indirect supervision was compared with that of operations conducted by the trainers and supervisors (observed). Progression towards surgical maturity was evaluated based on how trainees' roles during operations developed throughout training. Annual volume of operations performed (indirectly supervised) by the SACHOs was employed as a measure of productivity and to calculate potential future contributions to surgical volume. Productivity was compared against previously documented surgical productivity in Sierra Leone15, 19.

Results are reported in accordance with guidelines for implementation and operational research27. All hospitals that took part in the training agreed to share the surgical data (Table S1, supporting information). Trainees and SACHOs supplied written informed consent to share non‐identifiable logbook data. The Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee granted ethical approval.

Statistical analysis

Differences in volumes of surgery between trainees and SACHOs and in‐hospital mortality risk were tested using the Pearson χ2 test. Age of patients was compared between groups by means of a t test. Factors associated with in‐hospital mortality were determined by univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis. The multivariable analysis was adjusted for trainee role, patient sex, urgency of surgery, operation and hospital type. Odds ratios (ORs) are reported with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All tests were two‐tailed and statistical significance was set at P < 0·050. Missing data were excluded from the analyses.

Results

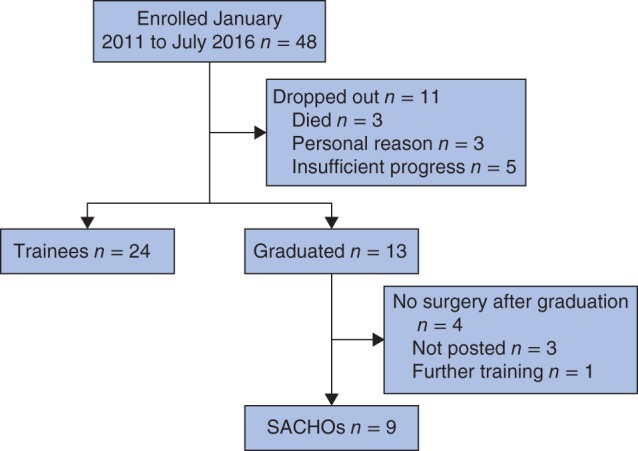

Forty‐eight trainees, two junior MDs and 46 CHOs, enrolled in the STP between January 2011 and July 2016 (Table 1). Three died (Ebola 2, motor accident 1) and three left for personal reasons (chronic sickness 1, emigration 1, lack of motivation 1). Five were removed from the programme because of insufficient progress, mostly during the initial 6 months (Fig. 3). Forty‐four international trainers conducted 78 training visits to Sierra Leone, delivering 47 training modules. Twelve CHOs and one MD graduated, of whom eight are currently posted as SACHOs in district hospitals and one in a referral hospital. Four graduates have not yet recorded any operations (1 MD continued postgraduate surgical training in Ghana, 3 graduates were posted after July 2016).

Table 1.

Key performance indicators of the surgical training programme until July 2016

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016* | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trainees | ||||||||

| Applicants | 1 | 11 | 45 | 36 | 24 | 39 | 14 | 170 |

| New trainees enrolled | 0 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 48 |

| MDs graduated | – | – | – | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| CHOs graduated | – | – | – | 0 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 12 |

| Dropout | – | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 11 |

| Trainer resources | ||||||||

| Modules taught | 1 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 47 |

| International trainers | 3 | 10 | 13 | 20 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 78† |

| Partner hospitals | 0 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 16 | 16 |

| Operations attended/performed | ||||||||

| Trainees | – | 849 | 3321 | 6865 | 4765 | 5010 | 3462 | 24 272 (89·2) |

| SACHOs | – | – | – | – | 260 | 1575 | 1109 | 2944 (10·8) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

January to July.

A total of 44 international trainees made 78 training visits.

MD, medical doctor; CHO, community health officer; SACHO, surgical assistant community health officer.

Figure 3.

Status of trainees and surgical assistant community health officers (SACHOs) by July 2016

Productivity

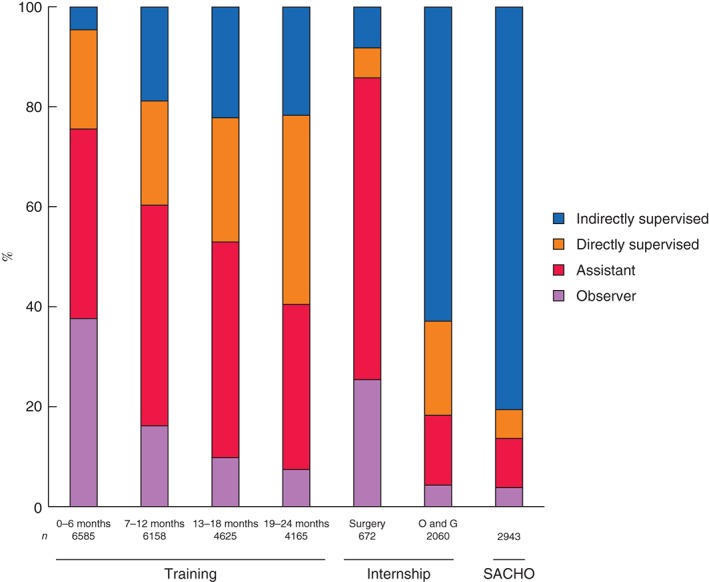

Forty‐eight trainees and nine SACHOs logged 27 216 operative training and service delivery episodes during the study period, 24 272 as trainees and 2944 as SACHOs. Those who completed the programme (13 graduates) took part in a median of 274 (237–322) surgical procedures annually, a median total of 822 per trainee during the 3 years of training (Table 2). The nine posted SACHOs took part in a median of 204 surgical procedures annually, and 173 (i.q.r. 109–226) were supervised indirectly. Caesarean section, hernia repair and laparotomy were the most frequent operations both during training and after graduation. Except for the surgical internship, the proportion of procedures performed by the trainees increased the further they were into the training (Fig. 4). Some 80·5 per cent of operations recorded by the SACHOs were indirectly supervised (2369 of 2944). Caesarean sections accounted for 43·8 per cent of the SACHO operations (1290 of 2944).

Table 2.

Annual volume of surgical procedures

| Annual no. of surgical procedures | ||

|---|---|---|

| During training | After training | |

| (13 graduated) | (9 SACHOs) | |

| Caesarean section | 83 (67–94) | 96 (62–108) |

| Hernia repair | 72 (64–85) | 41 (35–68) |

| Laparotomy | 22 (18–30) | 9 (8–10) |

| Appendicectomy | 8 (7–11) | 7 (5–18) |

| Dilatation and curettage | 9 (6–13) | 9 (1–16) |

| Hysterectomy | 8 (5–10) | 3 (2–8) |

| Other | 84 (76–96) | 46 (23–57) |

| Overall | 274 (237–322) | 204 (128–266) |

Values are median (i.q.r.). SACHO, surgical assistant community health officer.

Figure 4.

Role during surgical procedures by 6‐month intervals during training (training + internship) and after graduation (surgical assistant community health officer, SACHO). O and G, obstetrics and gynaecology

Compared with the trainees, the SACHOs participated in more operations in government hospitals (27·1 versus 58·1 per cent; P < 0·001) and more emergency operations (46·2 versus 69·2 per cent; P < 0·001), operated on younger patients (P < 0·001) and were more likely to operate on female patients (57·7 versus 71·0 per cent; P < 0·001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Operative data during training and after graduation

| During training† (n = 24 272) | After graduation‡ (n = 2944) | P § | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role of trainee or SACHO | < 0·001 | ||

| Observer | 4515 (18·6) | 114 (3·9) | |

| Assistant | 9311 (38·4) | 290 (9·9) | |

| Directly supervised | 5724 (23·6) | 170 (5·8) | |

| Indirectly supervised | 4715 (19·4) | 2369 (80·5) | |

| Missing | 7 (0·0) | 1 (0·0) | |

| Age of patient (years)* | 32·6(16·5) | 30·3(14·0) | < 0·001¶ |

| Sex | < 0·001 | ||

| M | 10 244 (42·2) | 853 (29·0) | |

| F | 14 016 (57·7) | 2090 (71·0) | |

| Missing | 12 (0·1) | 1 (0·0) | |

| Urgency | < 0·001 | ||

| Planned | 13 031 (53·7) | 905 (30·7) | |

| Emergency | 11 222 (46·2) | 2037 (69·2) | |

| Missing | 19 (0·1) | 2 (0·1) | |

| Surgical procedure | < 0·001 | ||

| Caesarean section | 6438 (26·5) | 1290 (43·8) | |

| Hernia repair | 6471 (26·7) | 610 (20·7) | |

| Laparotomy | 2142 (8·8) | 232 (7·9) | |

| Appendicectomy | 834 (3·4) | 134 (4·6) | |

| Dilatation and curettage | 866 (3·6) | 100 (3·4) | |

| Hysterectomy | 667 (2·7) | 67 (2·3) | |

| Other | 6854 (28·2) | 511 (17·4) | |

| Hospital | < 0·001 | ||

| Government | 6577 (27·1) | 1709 (58·1) | |

| Private non‐profit | 17 643 (72·7) | 1235 (41·9) | |

| Missing | 52 (0·2) | 0 (0) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean(s.d.).

Forty‐eight trainees;

nine surgical assistant community health officers (SACHOs).

Pearson χ2 test, except

two‐sample t test.

Safety

The crude in‐hospital mortality rate for all operations recorded as involving trainees was 1·9 per cent (466 of 24 256); it was 2·6 per cent (116 of 4513) for observed operations and 0·8 per cent (36 of 4714) for indirectly supervised operations (Table 4). Mortality following observed caesarean sections was 1·2 per cent (8 of 688) and 0·7 per cent (13 of 1915) for indirectly supervised procedures. The mortality rate was 7·5 per cent (53 of 703) after observed and 4·3 per cent (7 of 164) for indirectly supervised laparotomies. The risk of a fatal outcome after adjustment for patient sex, surgical procedure, urgency and hospital type was significantly lower for operations the trainees performed under indirect supervision versus observed operations (OR 0·47, 95 per cent c.i. 0·32 to 0·71; P < 0·001). A comparison of case mix between the observed and indirectly supervised surgical procedures for trainees and SACHOs is provided in Table S1 (supporting information).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with in‐hospital mortality during training (48 trainees, 24 272 surgical training episodes)

| Died* | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Missing | Odds ratio† | P | Odds ratio† | P | ||

| Student role | |||||||

| Observer | 4397 | 116 (2·6) | 2 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Assistant | 9075 | 225 (2·4) | 11 | 0·94 (0·75, 1·18) | 0·592 | 0·99 (0·78, 1·25) | 0·915 |

| Directly supervised | 5633 | 89 (1·6) | 2 | 0·60 (0·45, 0·79) | < 0·001 | 0·74 (0·55, 0·99) | 0·045 |

| Indirectly supervised | 4678 | 36 (0·8) | 1 | 0·29 (0·20, 0·42) | < 0·001 | 0·47 (0·32, 0·71) | < 0·001 |

| Missing | 7 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| M | 9974 | 262 (2·6) | 8 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| F | 13 804 | 204 (1·5) | 8 | 0·56 (0·47, 0·68) | < 0·001 | 0·43 (0·35, 0·54) | < 0·001 |

| Missing | 12 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Urgency | |||||||

| Planned | 12 907 | 120 (0·9) | 4 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Emergency | 10 865 | 345 (3·1) | 12 | 3·42 (2·77, 4·21) | < 0·001 | 4·05 (3·18, 5·15) | < 0·001 |

| Missing | 18 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Surgical procedure | |||||||

| Caesarean section | 6383 | 54 (0·8) | 1 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Hernia repair | 6435 | 33 (0·5) | 3 | 0·61 (0·39, 0·94) | 0·024 | 0·68 (0·41, 1·13) | 0·135 |

| Laparotomy | 1937 | 199 (9·3) | 6 | 12·14 (8·95, 16·48) | < 0·001 | 7·14 (5·06, 10·08) | < 0·001 |

| Appendicectomy | 826 | 8 (1·0) | 0 | 1·14 (0·54, 2·41) | 0·722 | 0·93 (0·44, 2·00) | 0·861 |

| Dilatation and curettage | 860 | 6 (0·7) | 0 | 0·82 (0·35, 1·92) | 0·655 | 0·97 (0·41, 2·23) | 0·917 |

| Hysterectomy | 654 | 13 (1·9) | 0 | 2·34 (1·28, 4·33) | 0·006 | 3·62 (1·93, 6·79) | < 0·001 |

| Other | 6695 | 153 (2·2) | 6 | 2·70 (1·98, 3·69) | < 0·001 | 2·78 (1·96, 3·95) | < 0·001 |

| Hospital | |||||||

| Government | 6510 | 67 (1·0) | 0 | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Private non‐profit | 17 228 | 399 (2·3) | 16 | 2·25 (1·73, 2·92) | < 0·001 | 1·54 (1·16, 2·03) | 0·003 |

| Missing | 52 | 0 | 0 | ||||

Values in parentheses are

percentages and

95 per cent confidence intervals.

The SACHOs recorded an overall mortality rate of 1·7 per cent (51 of 2944), 9·6 per cent (11 of 114) for observed operations and 0·8 per cent (20 of 2369) per cent for indirectly supervised procedures (Table 5). Adjusted analysis of operations conducted by the SACHOs under indirect supervision showed a significantly lower risk of a fatal outcome compared with operations the SACHOs observed (OR 0·16, 95 per cent c.i. 0·07 to 0·41; P < 0·001). Postoperative mortality for procedures carried out by SACHOs with indirect supervision was 0·4 per cent (5 of 1169) for caesarean sections and 8·0 per cent (11 of 137) for laparotomies.

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with in‐hospital mortality after graduation (9 surgical assistant community health officers, 2944 operations)

| Died* | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Odds ratio† | P | Odds ratio† | P | ||

| Student role | ||||||

| Observer | 103 | 11 (9·6) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Assistant | 273 | 17 (5·9) | 0·58 (0·26, 1·29) | 0·182 | 0·65 (0·26, 1·65) | 0·364 |

| Directly supervised | 167 | 3 (1·8) | 0·17 (0·05, 0·62) | < 0·001 | 0·12 (0·02, 0·50) | 0·004 |

| Indirectly supervised | 2349 | 20 (0·8) | 0·11 (0·06, 0·20) | < 0·001 | 0·16 (0·07, 0·41) | < 0·001 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| M | 819 | 34 (4·0) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| F | 2073 | 17 (0·8) | 0·20 (0·11, 0·36) | < 0·001 | 0·19 (0·09, 0·39) | < 0·001 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Urgency | ||||||

| Planned | 899 | 6 (0·7) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Emergency | 1992 | 45 (2·2) | 3·38 (1·44, 7·96) | 0·005 | 3·95 (1·48, 10·59) | 0·006 |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Surgical procedure | ||||||

| Caesarean section | 1284 | 6 (0·5) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Hernia repair | 607 | 3 (0·5) | 1·06 (0·26, 4·24) | 0·937 | 0·50 (0·10, 2·62) | 0·412 |

| Laparotomy | 202 | 30 (12·9) | 31·78 (13·06, 77·32) | < 0·001 | 10·51 (3·77, 29·26) | < 0·001 |

| Appendicectomy | 134 | 0 (0) | – | – | – | – |

| Dilatation and curettage | 100 | 0 (0) | – | – | – | – |

| Hysterectomy | 67 | 0 (0) | – | – | – | – |

| Other | 499 | 12 (2·3) | 5·14 (1·92, 13·78) | < 0·001 | 1·49 (0·44, 4·94) | 0·513 |

| Hospital | ||||||

| Government | 1694 | 15 (0·9) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) | ||

| Private non‐profit | 1199 | 36 (2·9) | 3·39 (1·85, 6·22) | < 0·001 | 1·50 (0·72, 3·11) | 0·277 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | ||||

Values in parentheses are

percentages and

95 per cent confidence intervals.

Future contributions to surgical volume

If the productivity of the SACHOs remains at a median of 173 (i.q.r. 109–226) operations a year, 60 SACHOs will perform 10 404 (6528–13 566) operations annually in Sierra Leone in 2021. If 44 per cent of the operations continue to be caesarean sections, they will carry out 4578 (2872–5969) sections annually.

Discussion

During training, the volume of surgical training episodes was high and there seemed to be progression towards surgical maturity, with exposure corresponding to procedures performed after graduation. Both trainees and SACHOs experienced lower in‐hospital mortality for operations they conducted under indirect supervision than in the observed operations carried out by their trainers and supervisors. The programme has been able to train in private non‐profit hospitals and transfer graduates to government district hospitals. The current productivity of the SACHOs indicates that task‐shared surgical providers can perform a considerable volume of emergency surgery at district government hospitals in the near future.

The primary strength of this study is the large prospectively registered number of operative training episodes that were included. The major challenges were related to the Ebola outbreak, which not only caused the tragic deaths of two students, but also placed all those involved under such risk that the programme was forced to shut down for nearly a year during the peak of Ebola transmission28. Unstable access to trainers and rapid changes in healthcare priorities among the partner hospitals during and after the Ebola outbreak were also challenging.

The major limitations of the study are that participants themselves recorded the operations and their outcomes, with a potential for reporting bias. Negative outcomes may be reported less than positive ones, possibly contributing to a general underestimation of mortality. Validation of logbook entries by local trainers and supervisors, however, should counteract this. The same operation may have multiple attendants of this programme, as a trainee might observe while a SACHO carries out the operation under indirect supervision. Assessing the safety of surgery based on crude postoperative in‐hospital mortality has its limitations, partly because crude mortality depends on many non‐surgical factors and partly because the in‐hospital mortality rate is often low. Morbidity outcomes, especially those more related to the surgical procedure, would better expose quality of practice offered by the surgical provider, but such data were not available for this study.

Safety of surgery is of utmost importance in any training programme, no matter what resources are available29. The postoperative mortality of indirectly supervised caesarean sections carried out by trainees (0·7 per cent) and SACHOs (0·4 per cent) was no higher than the rate reported previously from Sierra Leone (1·2 per cent, 4 of 338)25, or by a systematic review30 (median 1·4 per cent) including 19 publications from western Sub‐Saharan Africa. In addition, the postoperative mortality of indirectly supervised laparotomies performed by trainees (4·3 per cent) and SACHOs (8·0 per cent) was no greater than previously reported mortality in Sierra Leone (10·1 per cent, 18 of 178)26 or a recently established 30‐day mortality rate (8·7 per cent, 114 of 1316) from a multicountry low‐Human Development Index setting31.

Although the analyses were adjusted for sex, urgency, surgical procedure and hospital type, the observed operations as reference for mortality were still prone to selection bias as there was no adjustment for co‐morbidity and severity of the surgical condition. Poorer outcomes for patients operated on by trainers compared with trainees are also found in high‐income settings32, and difference in case mix has been suggested as an explanation for this. The procedures conducted by the trainers and supervisors in the present study may have been more complex than those undertaken by trainees and SACHOs, limiting the comparability of performance between the groups. Safety in surgery has much to do with selection of who is to operate on whom, when and where. High‐risk patients should be handled by the most competent providers. Comparing mortality between the supervision groups gives an indication on how operative risks are distributed, and is therefore a relevant measure of safety of the programme and the introduction of a new cadre. Procedures on high‐risk patients seem to be used less often for training purposes, the more experienced supervisors seem to resume responsibility for the more challenging operations, and the SACHOs refer or call for assistance when needed.

SACHOs were almost twice as productive as surgical providers in government hospitals in 201215. The high proportion of operations conducted with only indirect supervision indicates that task‐sharing is accepted by the existing surgical providers in district government hospitals. As all (except 1) of the SACHOs work in district hospitals, and more than two‐thirds of the patients operated on are women, it seems that the programme is able to target the most vulnerable part of the population – females of reproductive age living in the provinces. The 10 404 operations this programme is projected to complete annually by 2021 corresponds to an increase of 110 per cent compared with the 9500 operations performed in all government hospitals in 201219. Assuming annual population growth continues at 1·9 per cent33 for the second part of this decade and other surgical providers maintain levels of surgical activity found in 201219, the country will perform 435 operations per 100 000 inhabitants in 2021, still far below the universal target of 5000 annual operations the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery4 recently suggested. An additional 4162 caesarean sections represent an increase of 160 per cent from the 2012 level of activity in government hospitals19.

This programme could not have been established without the willingness of a broad range of diverse private non‐profit hospitals to align under one common training scheme. There have been surgical training initiatives in Sierra Leone before the STP34, 35, 36, 37, 38, but no systematic use of private non‐profit hospitals, where the majority of the surgery in the country is performed19. As others have also suggested39, the capacity and expertise among international institutions offering surgical services in low‐income countries should be better utilized for capacity building and training.

Another important strategy has been the use of short‐term international volunteers to supplement the insufficient volume of available local tutors. Short‐term surgical missions might not be sustainable40; however, in the Sierra Leonean context, the extreme shortage of skilled surgical providers has necessitated importing a wide range of specialists with dedicated time for intensive teaching and training. As seen with repeated short‐course training of laparoscopic skills in Mongolia41, deployment undertaken in a systematic way over many years can be fruitful. The combination of engagement of tutor capacity in the private non‐profit sector and the structured and long‐term commitment of international volunteers on short‐term visits could also be replicated in other highly underserved settings42.

Introduction of surgical task‐sharing must include regulation, mentoring and supervision of clinical activity, remuneration of professional development and acceptance of the new cadre43. If neglected, there is a considerable risk of drainage towards urban areas, the private non‐profit sector or even non‐clinical positions, if better rewarded44. Lack of remuneration and poor carrier pathways might be reasons for difficulties in attracting junior MDs to the STP. To date there is no legal protection for SACHOs in Sierra Leone, and there is no regulating body formally overseeing the medical practices of the CHO cadre. This makes clinical governance challenging, with both patient and healthcare practitioner safety poorly attended to. Currently, this is resolved at the hospital level where individual MDs assume informal responsibility and supervisory duties for the work performed by SACHOs. High turnover of MDs in government district hospitals makes this system fragile and in need of continued surveillance. Hospital visits by CapaCare medical staff and trainers, together with an annual surgical meeting, offer some mentoring to the SACHOs; however, this needs further development and the involvement of senior Sierra Leonean specialists.

Further research on the outcomes of operations offered within task‐sharing initiatives is required, with recording of postoperative morbidity events related to the surgical procedure, as this will better reveal the quality of operative skills. The long‐term implications of introducing task‐sharing, referral patterns, optimal mixes of surgical health cadres, and how barriers to access surgical care are affected, all need further investigation.

Overall, this study has indicated that the training of associate clinicians within a structure where government and private non‐profit district hospitals are brought under one training umbrella, in combination with systematic deployment of international volunteer specialists on short‐term rotations, is feasible and safe. The model provides high exposure to surgical training episodes and makes efficient use of limited local trainers. Currently, the programme is on track to deliver 60 additional surgical providers by 2021, all bestowed with the ability to be more productive than the existing surgical workforce without compromising the safety of surgical services offered. The potential gains are considerable, and it appears to reach the most vulnerable part of the population – women living in the provinces. Crucial for maintaining quality of care and retention in surgical service delivery in the provinces is to offer structured mentoring, adequate remuneration, and to strengthen clinical governance by developing more robust systems for regulation and supervision of surgical activities.

Supporting information.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix S1 Template memorandum of understanding between CapaCare and partner hospital (Word document)

Appendix S2 Post‐Graduate Surgical Training Curriculum – extracts from the student guide (Word document)

Appendix S3 Logbooks and evaluation schemes (Word document)

Table S1 Operative data for observed and indirectly supervised surgical procedures during training and after graduation (Word document)

Editor's comments

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Template memorandum of understanding between CapaCare and partner hospital (Word document)

Appendix S2 Post‐Graduate Surgical Training Curriculum – extracts from the student guide (Word document)

Appendix S3 Logbooks and evaluation schemes (Word document)

Table S1 Operative data for observed and indirectly supervised surgical procedures during training and after graduation (Word document)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support in terms of planning of both the study and the training programme, surgical training provided and teaching the trainees to collect data. They thank the Sierra Leonean‐based international coordinators of the training programme, D. van Leerdam and M. Grootjans; Dutch tropical doctors on long‐term contracts at the main teaching location, Masanga Hospital: F. van Raaij, J. Westendorp, C. Bijen, M. Oostvogels and J. van Kesteren; the founders of the Masanga Hospital Rehabilitation Project for housing the STP, P. B. Jørgensen and S. Haas, who also acted as trainers; CapaCare's accountant, A. van Duinen, for administrative support regarding finances related to the study; and all the dedicated volunteer international trainers, in particular L. M. Hunt who also critically reviewed the manuscript. The programme and the study would never have been initiated without the support of D. A. Bash‐Taqi (former Director of Hospitals and Laboratory Services of the MoHS), A. Conteh, Chief CHO (MoHS) and Chief Obstetrician, and A. P. Koroma, at Princess Christina Maternity Hospital, Freetown.

The Norwegian University of Science and Technology funded all parts of the study. The funding source had no role in any aspect of the study.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Preliminary results presented to the 54th Annual Conference of the West African College of Surgeons, Kumasi, Ghana, February 2014, and the 56th Annual Conference of the West African College of Surgeons, Yaoundé, Cameroon, February 2016

References

- 1. Bergström S, McPake B, Pereira C, Dovlo D. Workforce innovations to expand the capacity for surgical services In Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 1): Essential Surgery, Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A, Jamison DT, Kruk ME, Mock CN. (eds). World Bank Publications: Washington, 2015; 307–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . Task Shifting: Rational Redistribution of Tasks among Health Workforce Teams: Global Recommendations and Guidelines. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/TTR‐TaskShifting.pdf?ua=1 [accessed 5 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . Optimizing Health Worker Roles to Improve Access to Key Maternal and Newborn Health Interventions Through Task Shifting. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/978924504843/en/index.html [accessed 5 December 2016]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA et al Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015; 386: 569–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kruk ME, Pereira C, Vaz F, Bergström S, Galea S. Economic evaluation of surgically trained assistant medical officers in performing major obstetric surgery in Mozambique. BJOG 2007; 114: 1253–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoyler M, Hagander L, Gillies R, Riviello R, Chu K, Bergström S et al Surgical care by non‐surgeons in low‐income and middle‐income countries: a systematic review. Lancet 2015; 385(Suppl 2): S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beard JH, Oresanya LB, Akoko L, Mwanga A, Mkony CA, Dicker RA. Surgical task‐shifting in a low‐resource setting: outcomes after major surgery performed by nonphysician clinicians in Tanzania. World J Surg 2014; 38: 1398–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilson A, Lissauer D, Thangaratinam S, Khan KS, MacArthur C, Coomarasamy A. A comparison of clinical officers with medical doctors on outcomes of caesarean section in the developing world: meta‐analysis of controlled studies. BMJ 2011; 342: d2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pereira C, Cumbi A, Malalane R, Vaz F, McCord C, Bacci A et al Meeting the need for emergency obstetric care in Mozambique: work performance and histories of medical doctors and assistant medical officers trained for surgery. BJOG 2007; 114: 1530–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mkandawire N, Ngulube C, Lavy C. Orthopaedic clinical officer program in Malawi: a model for providing orthopaedic care. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466: 2385–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chilopora G, Pereira C, Kamwendo F, Chimbiri A, Malunga E, Bergström S. Postoperative outcome of caesarean sections and other major emergency obstetric surgery by clinical officers and medical officers in Malawi. Hum Resour Health 2007; 5: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mullan F, Frehywot S. Non‐physician clinicians in 47 sub‐Saharan African countries. Lancet 2007; 370: 2158–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. WHO . World Health Assembly Resolution A68/31: Strengthening Emergency and Essential Surgical Care and Anaesthesia as a Component of Universal Health Coverage. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA68/A68_31‐en.pdf [accessed 5 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vaughan E, Sesay F, Chima A, Mehes M, Lee B, Dordunoo D et al An assessment of surgical and anesthesia staff at 10 government hospitals in Sierra Leone. JAMA Surg 2015; 150: 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bolkan HA, Hagander L, von Schreeb J, Bash‐Taqi D, Kamara TB, Salvesen Ø et al The surgical workforce and surgical provider productivity in Sierra Leone: a countrywide inventory. World J Surg 2016; 40: 1344–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ministry of Health and Sanitation . National Health Sector Strategic Plan 2010– 2015; 2009 http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/fileadmin/uploads/ihp/Documents/Country_Pages/Sierra_Leone/NationalHealthSectorStrategicPlan_2010‐15.pdf [accessed 5 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dare AJ, Lee KC, Bleicher J, Elobu AE, Kamara TB, Liko O et al Prioritizing surgical care on national health agendas: a qualitative case study of Papua New Guinea, Uganda, and Sierra Leone. PLoS Med 2016; 13: e1002023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Groen RS, Samai M, Stewart KA, Cassidy LD, Kamara TB, Yambasu SE et al Untreated surgical conditions in Sierra Leone: a cluster randomised, cross‐sectional, countrywide survey. Lancet 2012; 380: 1082–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bolkan HA, Von Schreeb J, Samai MM, Bash‐Taqi DA, Kamara TB, Salvesen O et al Met and unmet needs for surgery in Sierra Leone: a comprehensive, retrospective, countrywide survey from all health care facilities performing operations in 2012. Surgery 2015; 157: 992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. WHO . Integrated Management for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (IMEESC) Tool Kit. http://www.who.int/surgery/publications/imeesc/en/ [accessed 5 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Transformative Education for Health Professionals . Sierra Leone's Community Health Officers. http://whoeducationguidelines.org/content/sierra‐leone's‐community‐health‐officers [accessed 17 January 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Masanga Hospital. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masanga_Hospital [accessed 5 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Supervision Code Help Guide – eLogbook. https://www.elogbook.org/rcsed/messageboard/displayfile.aspx?attachmentId=539 [accessed 5 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ng‐Kamstra JS, Greenberg SL, Kotagal M, Palmqvist CL, Lai FY, Bollam R et al Use and definitions of perioperative mortality rates in low‐income and middle‐income countries: a systematic review. Lancet 2015; 385: S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chu K, Maine R, Trelles M. Cesarean section surgical site infections in sub‐Saharan Africa: a multi‐country study from Medecins Sans Frontieres. World J Surg 2015; 39: 350–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McConkey SJ. Case series of acute abdominal surgery in rural Sierra Leone. World J Surg 2002; 26: 509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hales S, Lesher‐Trevino A, Ford N, Maher D, Ramsay A, Tran N. Reporting guidelines for implementation and operational research. Bull World Health Organ 2016; 94: 58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Milland M, Bolkan HA. Enhancing access to emergency obstetric care through surgical task shifting in Sierra Leone: confrontation with Ebola during recovery from civil war. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015; 94: 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van der Leeuw RM, Lombarts KM, Arah OA, Heineman MJ. A systematic review of the effects of residency training on patient outcomes. BMC Med 2012; 10: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Uribe‐Leitz T, Jaramillo J, Maurer L, Fu R, Esquivel MM, Gawande AA et al Variability in mortality following caesarean delivery, appendectomy, and groin hernia repair in low‐income and middle‐income countries: a systematic review and analysis of published data. Lancet Glob Health 2016; 4: e165–e174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. GlobalSurg Collaborative . Mortality of emergency abdominal surgery in high‐, middle‐ and low‐income countries. Br J Surg 2016; 103: 971–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kelly M, Bhangu A, Singh P, Fitzgerald JE, Tekkis PP. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of trainee‐ versus expert surgeon‐performed colorectal resection. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 750–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. UN Data . World Statistics Pocketbook – Sierra Leone. http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=sierra%20leone [accessed 17 January 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mante SD, Gueye SM. Capacity building for the modified filarial hydrocelectomy technique in West Africa. Acta Trop 2011; 120(Suppl 1): S76–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leow JJ, Groen RS, Kamara TB, Dumbuya SS, Kingham TP, Daoh KS et al Teaching emergency and essential surgical care in Sierra Leone: a model for low income countries. J Surg Educ 2011; 68: 393–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bräuer MD, Antón J, George PM, Kuntner L, Wacker J. Handling postpartum haemorrhage – obstetrics between tradition and modernity in post‐war Sierra Leone. Trop Doct 2015; 45: 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sivarajah V, Tuckey E, Shanmugan M, Watkins R. Surgical training during a voluntary medical‐surgical camp in Sierra Leone. Br J Surg 2013; 100: 156–157. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kushner AL, Kamara TB, Groen RS, Fadlu‐Deen BD, Doah KS, Kingham TP. Improving access to surgery in a developing country: experience from a surgical collaboration in Sierra Leone. J Surg Educ 2010; 67: 270–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ng‐Kamstra JS, Riesel JN, Arya S, Weston B, Kreutzer T, Meara JG et al Surgical non‐governmental organizations: global surgery's unknown nonprofit sector. World J Surg 2016; 40: 1823–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nthumba PM. ‘Blitz surgery’: redefining surgical needs, training, and practice in sub‐Saharan Africa. World J Surg 2010; 34: 433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vargas G, Price RR, Sergelen O, Lkhagvabayar B, Batcholuun P, Enkhamagalan T. A successful model for laparoscopic training in Mongolia. Int Surg 2012; 97: 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grimes CE, Maraka J, Kingsnorth AN, Darko R, Samkange CA, Lane RH. Guidelines for surgeons on establishing projects in low‐income countries. World J Surg 2013; 37: 1203–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bergström S. Training non‐physician mid‐level providers of care (associate clinicians) to perform caesarean sections in low‐income countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2015; 29: 1092–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Munga MA, Kilima SP, Mutalemwa PP, Kisoka WJ, Malecela MN. Experiences, opportunities and challenges of implementing task shifting in underserved remote settings: the case of Kongwa district, central Tanzania. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2012; 12: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Template memorandum of understanding between CapaCare and partner hospital (Word document)

Appendix S2 Post‐Graduate Surgical Training Curriculum – extracts from the student guide (Word document)

Appendix S3 Logbooks and evaluation schemes (Word document)

Table S1 Operative data for observed and indirectly supervised surgical procedures during training and after graduation (Word document)