Abstract

The number of caesarean sections increased significantly in Romania. In 2012, caesarean sections accounted for 41.2% of total births, according to a study of the Romanian National School for Public Health. This estimation is in agreement with the statistical data on caesarean sections recorded in one of the most important hospitals in Bucharest, Romania, Filantropia Hospital.

Many factors have influenced the large number and sharply increasing trend of caesarean sections, from the historical ones, with roots in the communist regime, when abortions were outlawed, to current day doctors’ medical practices and mothers’ beliefs and fears related to the process of labor and the newborn’s health.

This paper aims to examine the pros and cons for caesarean birth. The analysis is presented from three perspectives: expressed by the doctor/medical caregiver, the patient/mother and some of the third parties indirectly involved in the medical decision: the foetus/newborn, the hospital/medical unit and the society as a whole, knowing that ethics is beyond the legal, economic or administrative frames.

Keywords:caesarean section, Romania, ethics, autonomy, maternal decision

INTRODUCTION

In the last two decades, Romania has been facing a significant decrease in fertility and number of births. These negative trends originate from the communist period that left a strong mark on the health care system. One of Nicolae Ceausescu’s goals was the growth of the Romanian population up to 30 million persons. In this vain, in 1966, the Decree 770 was promulgated, outlawing abortion and use of contraception; at that time, prohibiting caesarean surgery was considered to help increase the number of births, in line with the demographic policy of the communist party.

As a result, between 1966 and 1989, a number of 9,542 maternal deaths as a consequence of illegal abortions or birth-related complications was reported (1). Information about contraceptive methods and reproductive life were taboo, although officially, the family was considered “the vital cell of society”. Contraceptive methods were not available in any medical facility.

In the ‘80s, according to the local official statistics (Romanian National Institute for Statistics), the number of pregnant women and newborns followed a negative trend, decreasing from a maximum of 526,000 births registered in 1966, down to an average of 400,000 births .

In hospitals (all public), patients were able to choose their doctor and natural births were assisted by midwifes and doctors on call during early labor. In rural areas, some of the patients gave birth at home only with midwifes when no medical care was available nearby.

The number of newborns continued to drop significantly after the change of the political regime in 1989. A historical minimum was reached in 2013, when according to the Romanian National Institute for Statistics, the number of births in Romania dropped to 198,216 – a decline by of 63% compared to the maximum reach after the promulgation of the 1966 Decree.

Some important structural shifts were recorded as well, regarding the mother’s age and the geographic area (rural versus urban). The clinical recording and examination of pregnancies changed too. In 1970, the clinical recording of pregnant women was compulsory and 460,509 pregnant women were recorded. Currently, this number is significantly lower, following the demographic trend described above; thus, in 2011 only 130,756 pregnant women were clinically recorded by the Romanian National Institute for Statistics (2) .

Pregnant women’s age followed the European trend and women have become more careeroriented. At present, unmarried couples and single women are having babies. Women who work abroad or those who have financial possibilities can choose to give birth in Western countries.

Another important structural change was registered in the mode of delivery, from mainly vaginal births before 1990 to an important increase in caesarean sections in the last two decades. According to WHO (World Health Organization) data, in 1999, in Romania, caesarean sections represented 11% of the total number of births, whereas in 2010 they accounted for 30.4% of the total number of births (3).

In the last decade, information provided by mass-media, internet, friends’ family or other patients’ acquaintances has become an important assisting tool in deciding on a method of birth.

The increase in caesarean birth rate is associated with various aspects ranging from medical and financial ones to moral and ethical ones. These discussions are mainly involving the field of caesarean sections on request, without an obstetrical indication, performed at the mother’s request or sometimes at the doctor’s recommendation without a strong medical motivation.

The modern structure of medical ethics considers autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice when referring to a patient. When divergences occur between doctors and patients with respect to the choice of the delivery method, conflict may arise between the mother’s autonomy (and the respect for her own views, interests, beliefs and values) and the doctor’s autonomy (related to medical knowledge, risks involved, medical recommendations and clinical guides).

This paper aims to explain the recent trends in caesarean sections in Romania from three perspectives: expressed by the doctor/medical caregiver, the patient/mother and some of the third parties indirectly involved in the medical decision: the foetus/newborn, the hospital/medical unit and the society as a whole, knowing that ethics is beyond the legal, economic or administrative frames.

FIGURE 1.

FIGURE 1. Comparative evolution of the number of vaginal births vs caesarean deliveries in Filantropia Hospital, 2003-2013. Data source: Filantropia Hospital, Bucharest

FIGURE 2.

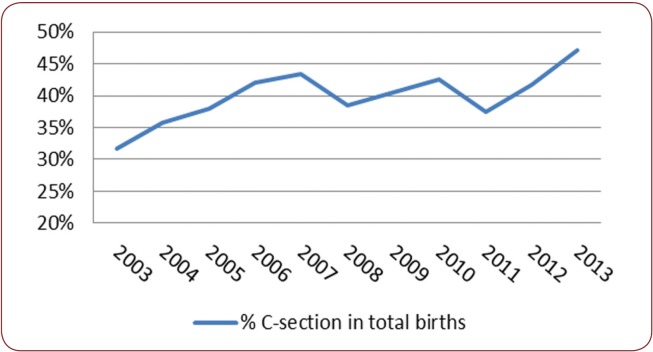

FIGURE 2. Evolution of caesarean section percentage in total births, Filantropia Hospital, Bucharest, Romania, 2003-2013. Data source: Filantropia Hospital, Bucharest, Romania

FIGURE 3.

FIGURE 3. Live-births in Romania by assistance at birth, 2013 Data source: National Institute for Statistics, Romania, TEMPO database

STATISTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The available official data on caesarean sections in Romania are quite limited. The WHO reports covers only a few years (the latest available value is for the year 2010).

National statistics on caesarean sections are not currently available. Therefore, we had to use only data from published studies and articles. For example, a study of the Romanian National School for Public Health reported that, in 2012, caesarean births accounted for 41.2% of the total births in the public hospitals. To have a more realistic view on the issue, the number of caesarean sections performed in private clinics (not officially reported), where the caesarean section rate is estimated to be around 60% (4), should be added to the aforementioned figure.

These values are similar to those registered in one of the largest hospitals in Bucharest – Filantropia University Hospital (the oldest Maternity in Romania). Here, in the last 10 years, caesarean sections accounted for about 40% of the total births.

Figure 1 presents the evolution of births in Filantropia Hospital, showing the contribution of vaginal births and caesarean sections. The evolution slightly oscillates from year to year in terms of number of births and mode of delivery.

The weight of caesarean section delivery varied from a minimum of 31.6 % of total births in 2003 up to 47.2% in 2014, as showed in Figure 2.

The caesarean section rate in Filantropia Maternity is explained by the large numbers of high risk pregnancies referred by other hospitals (both public and private units) as it provides Level III neonatal intensive care. Although the clinic offers specialised medical assistance for cases of extreme premature children as well as foetal pathologies, it does not perform caesarean sections on request, but only based on medical documents and obstetrical indications.

The increase in caesarean birth rate is associated with various aspects ranging from medical and financial ones to moral and ethical ones. These discussions are mainly involving the field of caesarean sections on request, without an obstetrical indication, performed at the mother’s request or sometimes at the doctor’s recommendation without a strong medical motivation.

The modern structure of medical ethics considers autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice when referring to a patient. When divergences occur between doctors and patients with respect to the choice of the delivery method, conflict may arise between the mother’s autonomy (and the respect for her own views, interests, beliefs and values) and the doctor’s autonomy (related to medical knowledge, risks involved, medical recommendations and clinical guides).

This paper aims to explain the recent trends in caesarean sections in Romania from three perspectives: expressed by the doctor/medical caregiver, the patient/mother and some of the third parties indirectly involved in the medical decision: the foetus/newborn, the hospital/medical unit and the society as a whole, knowing that ethics is beyond the legal, economic or administrative frames.

STATISTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

In Romania, most of the deliveries are performed by obstetricians and in 95% of the cases doctors are present either alone or with a midwife (Figure 3).

For university hospitals, the general procedure for caesarean section with indication is usually obtained by getting the Head of Department’s approval based on medical indications. When patients’ request to receive caesarean section surgery is refused, many of them go to private hospitals that respect their birth choice.

The caesarean section was introduced as a failure of natural birth due to special obstetrical conditions: placenta praevia, cephalo-pelvic disproportion, transversal presentation. Due to the electronic fetal monitoring during labor, given an uncertain foetal status, emergency caesarean surgery is performed to save the foetus and in the mother’s best interest. Instrumental extractions are usually indicated for bradycardia and prolonged foetal distress, as a correctly applied and assisted extraction using forceps has been proven to protect the foetus against perinatal hypoxia. Emergency caesarean section during expulsion would have a higher risk of neonatal convulsions compared to instrumental extractions (5).

In 2005, WHO showed that the risk of maternal death as a result of caesarean section surgery is 3- to 5-fold higher than that involved by natural birth; similarly, the risk of hysterectomy is two times higher than that involved by natural birth as well the risk to be admitted in the intensive care unit for more than 7 days (6).

Compared to caesarean section on demand, without medical indication, performed on the 39th week of pregnancy, caesarean surgery for either obstetrical reasons or performed during labor would have more complications due to the obstetrical pathology that indicated it (for example, the risk of uterine atony or postpartum haemorrhage is higher for placenta praevia). There are as well some debatable obstetrical indications for caesarean section such as foetal macrosomia for preventing shoulder dystocia, but there is no scientific evidence that caesarean section performed at the beginning of labor would be more efficient in this case (7).

Caesarean section increases the risk of infections (fever, endometritis, puerperal sepsis), haemorrhage, thrombophlebitis, thrombosis, and embolism. A retrospective analysis on a representative sample of 26,356 patients with no risk at their delivery due/planned date (either natural or via caesarean section) showed a significantly lower risk of chorioamnionitis, postpartum haemorrhage, uterine atony and prolonged rupture of membranes in the planned births with caesarean section compared to natural birth (8). In a metaanalysis on 13,000 women, Smaill FM et al. proved that caesarean section increased the risk for infection and infectious morbidity 20 times compared with vaginal birth and recommends antibiotic-prophylaxis (9).

The factors associated with increased risks for infection are those correlated to prolonged labor that finalizes with failure of vaginal birth and emergency caesarean section, surgery technique and length, anaemia, previous infections, obesity, and diabetes.

There is a slight risk increase in women who had 2 or more scare uterus: uterine rupture, risk of abnormal placentation (accreta), urinary bladder wounds and more laborious and sometimes haemorrhagic surgical interventions. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) do not recommend caesarean on demand to mothers who wish to have more than one child because of the increased surgery risk involved in subsequent pregnancies (10).

In Nigeria, Rukewe et al. found that 10.5% of a pregnant women population in a University Hospital had complications related to anaesthesia (due mainly to general anaesthesia) (11).

Lactation is starting later after caesarean section birth and mothers need more days to recover and take care of the newborn compared to natural birth.

For the foetus, natural birth and spontaneous labor seem to have fewer complications compared to caesarean section. In a randomised study of 116 pregnant women with one child, under 37 weeks of pregnancy, who entered into premature labor, Alfirevic et al. compared foetal and maternal complications after natural birth to those after caesarean section and found no significant differences in Apgar scores at 5 minutes, perinatal mortality, respiratory distress syndrome, ischemic encephalopathy and asphyxia at birth. There were reports on accidental knife injuries of soft spots in caesarean section surgery and one case of bruising at a vaginal birth, but no significant differences were recorded in the 5-minute Apgar score. Likewise, no significant differences in maternal complications were reported (12).

In time, natural birth can have some complications related to urinary and anal incontinence or sexual dysfunctions, with a notable impact on family and socio-economic life. Some studies are associating these complications with multi-parity and large weight of the child at birth (13). Handa et al. found a higher risk of urinary incontinence in patients with epidural analgesia, due to the prolonged expulsive efforts. As well, a correlation was found between urinary incontinence and instrumental extractions and spontaneous lacerations, but not with episiotomy (14).

Some authors suggest that pregnancy for patients over 30 years is considered to be a risk factor for urinary incontinence and pelvic floor dysfunction, but regardless whether delivery was by caesarean section or vaginal (15).

In conclusion, medical research, statistical data and findings from randomised studies show less medical risks for babies delivered vaginally and more complications in caesarean section for obstetrical indication for both the mother and the newborn.

THE DOCTOR’S PERSPECTIVE

The decision making process for the choice of delivery should be made together by the doctor and the mother. One of the most important ethical dilemmas for choosing a caesarean section relates to a proper understanding of the informed consent (16, 17).

In Romania, the informed consent was introduces in 2003; the Law 95/2006 on health care system reform stipulates that patients above 18 years are obliged to sign an agreement form. The patient has the right to be informed on the risks associated to the clinical investigations and treatments. Information is provided during a personal consult by the doctor (18).

The patient has the right to either express his/ her consent during hospitalisation or withdraw it after receiving the information from the medical team. Dima et all showed that 46% of the Romanian patients are only concerned by the main aspects of the medical procedures which they want to be explained in an understandable manner (19).

Sometimes, detailed medical information on the benefits and limitations of each of the delivery methods, tailored for the patient’s level of understanding, cannot be offered because doctors are overloaded and may be not too interested in providing detailed information to the patient.

Given the fear of legal consequences that might appear as a result of complications during labor, doctors could recommend a caesarean section even in the absence of medical indications. When acting this way, they have in mind their own time management, as the caesarean section allows scheduling of birth at a chosen date. Also, as a reminiscence of the communist past, the patient is a client in the patient-client relationship, and doctors recommend a caesarean section as a response to their patient’s desire, guided by the principle that providing a service to their “client’s satisfaction” means keeping ‘the client’. Such a way of working is abnormal not only for the patient, who has to wait for the doctor to deliver the baby in case of natural delivery, but also for the doctor, because it is impossible to answer all calls at all times.

For obstetricians, the major disadvantage of practicing caesarean sections without medical indication will be the lack of practical experience in obstetrical maneuvers (breech presentation, shoulder dystocia, instrumental extraction) and difficult foetal extraction even during caesarean surgery – when the extractions are made similarly to vaginal births (for example, femoral fractures, incorrect extractions in case of transversal presentation).

Doctors would like to act on their autonomy and make or not recommendations for caesarean based on their medical knowledge, involved risks, medical recommendations and clinical guides, which is sometimes in conflict with the mother’s autonomy to make her own choice on the delivery method.

MOTHER’S PERSPECTIVE

The patients’ degree of satisfaction during pregnancy and labor is intrinsically linked to their own value system, trust in their doctor, medical care provided by the hospital and the health system, in general. For example, in a Romanian dedicated setting for mothers there is the following statement: “In Filantropia Hospital, most of the doctors performing ultrasound for prenatal diagnosis are competent due to their training stages abroad”.

Patients expect to play an active part in decision making regarding the mode of delivery; in many cases, a caesarean section is preferred because mothers are afraid of a prolonged and painful labor, or not having permanent assistance from the medical staff during their labor, or many (yet improbable) medical complications (from episiotomies to the nuchal cord entanglement and foetus suffocation), or medical problems as a result of the use of a forceps or vacuum device. In most cases, these fears are explained by the mothers’ poor or insufficient understanding of the medical aspects related to vaginal delivery and caesarean section surgery, which is related not only to the insufficient communication between health professionals and patients but also to the patient’s level of medical education. Moreover, in Romania there are still disparities in the available medical information provided by doctors, which amplifies mothers’ confusion (e.g., information about foetal suffocation by nuchal cord entanglement or the use and results of forceps that may handicap the baby).

Nuchal cord is common. It may lead to perinatal asphyxia during labor, but the medical team can notice any changes in the electronic foetal heart rate during labor (20). It does not require prenatal screening and involves no medical reasons for caesarean section before labor (21). An experienced, board-certified obstetrician is skilled to identify these cases and perform a quick and safe instrumental extraction of a foetus with bradycardia. A loose nuchal cord can be easily slipped over the baby’s head to decrease traction during delivery of the shoulders.

Therefore, the fear of nucal cord as well as other medical conditions is mainly based on prejudgments, and not on medical evidence.

Pregnant women’s perception is that surgery is superior to vaginal birth. If complications appear, the doctor is capable of solving them (not necessarily true for all doctors). In Romania, patients with caesarean section believe they received better medical care than women with vaginal delivery. The level of pain is considered lower and easier to control, as no pain is felt during the operation and pain medication can be used postoperatively.

As the pregnant women tend to be older, some patients feel they are ’too old’ for a potentially long labor. In many cases, those with in vitro fertilization who receive anticoagulant therapy or recurrent abortion are asking for a caesarean section.

A traumatic experience with complications at the first/ previous vaginal delivery is also a cause of demanding a caesarean section.

Time management is also important especially for career-oriented mothers who need to have a rigorously planning of the birth (22).

Patients requiring caesarean sections are supporting their option by using a lot of arguments, but their level of medical understanding is often inappropriate. To exert their autonomy, mothers should have a full understanding of the risks and benefits involved by each delivery method.

THE THIRD PARTY PERSPECTIVE

The two major actors in making the decision about the method of delivery are the mother (patient) and the doctor. Other actors can as well indirectly influence the decision making process.

One of the third parties is the hospital, with its own policies and procedures. In Romania, the health care system is under-financed, and the National Health Insurance House allocates two to three times more money for caesarean section compared to vaginal birth (depending on complications). This might determine some hospitals to encourage caesarean sections as opposed to vaginal births.

Hospital under-financement also encourages private medicine to be practiced in public settings, raising several issues such as medical responsibility or improvement of medical care quality, and not clientele.

For the health system, a large number of caesarean sections will put financial pressure and will deplete the funds from other healthcare services. To decrease the number of unnecessary caesarean sections, Romania has just introduced the co-payment system for caesarean sections on demand, but it still needs to be enforced. Medical indications for caesarean section have to be standardized at national level and a robust system to ensure the application of recommendations should be implemented.

Another party who is directly affected by the result of birth method decision is the foetus/newborn. This party cannot express his/her own choice directly but as shown previously, in most of the cases, in the absence of medical indications, vaginal birth is more beneficial for the newborn as opposed to caesarean section. Therefore, it is important that both the mother and the doctor act together in the best interest of the foetus/newborn, as the latter cannot use his/ her right to personal autonomy.

CONCLUSION

The number of caesarean sections increased all over the world, but in Romania some evidence shows that more than 40% of the children are delivered through caesarean section.

As current medical evidence proves that vaginal birth involves less risk for both mother and newborn, the increase in the number of caesarean section raises some medical, ethical and financial concerns.

Mothers’ autonomy is an important issue too, but one the other hand, caesarean section without medical indication could lead to maternal and foetal medical risks linked to anaesthesia and surgical process.

The doctor and the mother should decide together on the choice of birth. The decision should be fully informed, as mothers have to clearly know and understand which are the benefits and risks of caesarean section surgery both for themselves and their newborn.

In Romania, the enforcement of the newly introduced co-payment system for caesarean sections on demand, based on standardization of medical indications for caesarean section, might reduce their number. Public hospitals as well as private clinics should have the same clinical indications and some control should exist to prevent abusive medical indications.

Change in the current – somehow distorted – perceptions and beliefs of Romanian women based on understanding of the real medical benefits/ risks involved and trust in the healthcare system can have a considerable impact on safe motherhood in Romania.

Autonomy – women’s right to make and act according to their own decision – is a complex concept. The mother’s decision should be based on correct medical information, and not on preconception or biased information from family members or the internet. Doctors and midwifes have an important role as they are implementing the informed consent. They also have autonomy based on their medical knowledge, but their recommendation should be clearly explained to mothers. Only a full understanding of the main benefits and risks of each delivery method can lead to a real enactment of the autonomy principle.

Conflict of interests: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

Acknowledgements: This paper was partially supported (for A.A. Simionescu) by the grant 20062/24.07.2014 from “Carol Davila”University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania. Special thanks to Professor Gheorghe Peltecu for providing access to statistical data regarding Filantropia Hospital.

Contributor Information

Anca A SIMIONESCU, ”Carol Davila” University of Medicine, Filantropia Hospital, Bucharest, Romania.

Erika MARIN, Department of Statistics and Econometrics, University of Economic Studies Bucharest, Romania.

REFERENCES

- Baban A. - Romania. In: From abortion to contraception: A resource to public policies and reproductive behavior in Central and Eastern Europe from 1917 to the present. HP David (ed.). Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. 1999; :191–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerul Sanatatii. Institutul National de Sanatate Publica. - Centrul National de Statistica si Informatica in Sanatate publica. Asistenta gravidelor si evidenta intreruperii cursului sarcinii in 2011 comparativ cu 2010. . ; [Google Scholar]

- EURO-PERISTAT Project with SCPE and EUROCAT - European Perinatal Health Report. The health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2010. May 2013. Available www.europeristat. . ; [Google Scholar]

- Vlad Mixich. - Jumatate din copiii romani NU se mai nasc pe cale naturala. De ce? HotNews.ro Luni, 22 aprilie 2013. http://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-opinii-14667820-jumatate-din-copiii-romani-numai-nasc-cale-naturala.htm. . ; [Google Scholar]

- Werner EF, Janevic TM , Illuzzi J, Funai EF, Savitz DA, Lipkind HS. - Mode of delivery in nulliparous women and neonatal intracranial injury. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1239–1246. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823835d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A, et al. - WHO 2005 global survey on maternal and perinatal health research group . Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006;367:1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68704-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankins GD, Clark SM, Munn MB - Cesarean section on request at 39 weeks: impact on shoulder dystocia, fetal trauma, neonatal encephalopathy, and intrauterine fetal demise. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30:276–287. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller EJ, Wu JM, Jannelli ML, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. - Maternal outcomes associated with planned vaginal versus planned primary caesarean delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27:675–683. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaill FM, Gyte GM. - Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1CD007482 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007482.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. - ACOG committee opinion no. 559: Cesarean delivery on maternal request. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:904–907. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000428647.67925.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukewe A, Fatiregun A, Adebayo K. - Anaesthesia for caesarean deliveries and maternal complications in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2014;43:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfi revic Z, Milan SJ, Livio S. - Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preterm birth in singletons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000078.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, Hunskaar S. - Vaginal delivery parameters and urinary incontinence: The Norwegian EPINCONT study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1268–1274. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa VL, Blomquist JL, McDermott KC, Friedman S, Muñoz A. - Pelvic fl oor disorders after vaginal birth: eff ect of episiotomy, perineal laceration, and operative birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:233–239. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240df4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leijonhufvud Å, Lundholm C, Cna" ingius S, Granath F, Andolf E, Altman D. - Risk of surgically managed pelvic floor dysfunction in relation to age at first delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:303. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mappes TA, Degrazia D. - Information, comprehension and voluntariness. Elective Caesarean Section: How informed is informed? Biomedical Ethics. 2001;5th Ed, New York, McGraw-Hill [Google Scholar]

- Zeidenstein L. - Elective Caesarean section: how informed is informed? OJHE. 2013;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- - Law 95/2006 on Health Care system. Offi cial Gaze$ e of Romania. ; [Google Scholar]

- Dima L,Repanovici A,Purcaru D, Rogozea L. - Informed consent and e-communication in medicine. Rev Rom Bioet. 2014;12 (2):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cohain JS. - Nuchal cords are necklaces, not nooses. Midwifery. Today Int Midwife. 2010;93:46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narang Y, Vaid NB, Jain S, Suneja A, Guleria K, Faridi MM, Gupta B. - Is nuchal cord justified as a cause of obstetrician anxiety? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:795–801. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildingsson I, Thomas JE. - Women’s perspectives on maternity services in Sweden: processes, problems, and solutions. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]