Abstract

Background

The effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART) depends on the choice of regimens during initiation. Most evidences from developed countries indicated that there is difference between efavirenz (EFV) and nevirapine (NVP). However, the evidences are limited in resource poor countries particularly in Africa. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out to summarize reported long-term treatment outcomes among people on first line therapy in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

Observational studies that reported odds ratio, relative risk, hazard ratio, or standardized incidence ratio to compare risk of treatment failure among HIV/AIDS patients who initiated ART with EFV versus NVP were systematically searched. Searches were conducted using the MEDLINE database within PubMed, Google Scholar, HINARI, and Research Gates between 2007 and 2016. Information was extracted using standardized form. Pooled risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using random-effect, generic inverse variance method.

Result

A total of 6394 articles were identified, of which, 29 were eligible for review and abstraction in sub-Saharan Africa. Seventeen articles were used for the meta-analysis. Of a total of 121,092 independent study participants, 76,719 (63.36%) were females. Of these, 40,480 (33.43%) initiated with NVP containing regimen. Two studies did not report the median CD4 cell counts at initiation. Patients who have low CD4 cell counts initiated with EFV containing regimen. The pooled effect size indicated that treatment failure was reduced by 15%, 0.85 (95%CI: 0.75–0.98), and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) switch was reduced by 43%, 0.57 (95%CI: 0.37–0.89).

Conclusion

The risk of treatment failure and NNRTI switch were lower in patients who initiated with EFV than NVP-containing regimen. The review suggests that initiation of patients with EFV-containing regimen will reduce treatment failure and NNRTI switch.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0567-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Treatment failure, NNRTI switch, First line ART regimen, Systematic review, Sub-Saharan Africa

Background

During the last three decades, HIV/AIDS has become the threat to the world. Almost 75 million people have been infected, and about 36 million people have died of HIV [1]. The introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) changes HIV/AIDS from diseases with a high mortality rate to manageable chronic diseases by decreasing the progression of AIDS and reducing HIV-related illness and deaths. Researches revealed that improved access to ART is helping to drive a decline in HIV-related morbidity and mortality [2–5]. In the USA and Canada, a person in his or her 20s who contracts HIV can now expect to live into the 70s if initiated ART early [6].

The standard therapy consists of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) [7]. In 2010, these guidelines were revised and recommended less toxic drugs in first-line therapy by replacing stavudine (d4T) with tenofovir (TDF) [8]. In resource-limited countries, World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of two NNRTI (nevirapine (NVP) and efavirenz (EFV)) as first-line ART regimen. EFV, combined with two NRTIs, is the recommended option for initial therapy and is the most widely used NNRTI [9].

Staying on an initial regimen medication that successfully suppresses viral replication is essential as it slows disease progression and preserves options for future treatment [3]. However, patients modify or switch their regimen due to different reasons. Toxicity is the most frequently reported reason for modifying or switching the first combined antiretroviral therapy regimens [10]. Once a drug combination is modified, it can no longer be given to the same patient again. It also causes significant morbidity and poor quality of life and also can be an important barrier to adherence, ultimately resulting in treatment failure and viral resistance [11]. Treatment failure due to different reasons is the challenge faced by the current ART scale up program especially in resource-limited countries [12, 13]. Where as the resource-rich countries have documented the effectiveness of the choice of initial regimen [14].

In resource-limited countries, the available evidences are not consistent with the effectiveness of NNRTI choice. In Cameroon, hematologic related adverse drug reaction was high among those who started ART which leads to treatment modification [15]. According to a Ghanaian study, the effectiveness of first-line ART (i.e., the proportion of patients who stay on the initial regimen) was 83.3% depending on virologic failure [16]. Documented virologic failure suggests that access to viral load measurements may actually reduce the rate of switching to a second-line regimen [17]. The substitution due to toxicity of NVP was higher, and according to [18], 8 and 2% substitute their initial regimen when initiated with NVP and EFV, respectively. Study in southern Ethiopia [19] showed that most modifications had occurred during the first 6 months of treatment.

Studies in resource-rich settings revealed that EFV-containing regimen has better treatment outcomes than NVP-containing regimen [20, 21]. In India, a randomized clinical trial [22] also showed that regimen containing NVP was inferior and was associated with more frequent virologic failure and death. Similarly, this pattern was reported in Swaziland, Zambia, and Botswana [23, 24]. However, studies in Ghana and Ethiopia indicated that there is comparable effect between EFV and NVP [16, 25].

The choice of treatment combinations for HIV-infected patients to initiate ART depends on cost and efficacy [7, 26]. Identifying the long-term treatment outcomes of these drugs is very decisive for clinical decision. Clinical decision-making requires ongoing reconciliation of studies that provide different answers to the same question. The above example indicates contradicting results in terms of the effectiveness of the drugs. Though studies showed significantly different effect on long-term treatment outcome in resource-rich settings among NNRTI groups, there was no strong evidence in resource-poor countries. Thus, local evidences as per the real setting of the population will assist the clinicians to focus on the most effective treatment combinations in resource-poor settings. This review aimed to investigate if treatment failure and NNRTI substitution are different between NVP and EFV containing initial regimen.

Methods

Search strategies

Comprehensive and exhaustive search strategy was made by two of the investigators to identify all relevant studies. MEDLINE through PubMed, Google Scholar, HINARI, and Research Gates were used to search for the relevant papers. Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) format was used to search the relevant studies. PROSPERO registration was not done.

For HIV-infected adults a combination of NRTI and NNRTI drugs has been given as first-line regimen. NVP and EFV are used as first-line drugs for most of the patients. The research question was “Does the choice of NNRTI drug affect the effectiveness of first line treatment?” The search strategy included Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and a range of relevant keywords. Combinations of keywords: (((((((((((((HIV) OR AIDS*) AND antiretroviral*) OR HAART*) OR ART*) OR ARV*) AND NNRTI*) AND outcomes*) OR treatment failure) OR switch) OR substitution) OR Discontinuation) AND Africa) OR sub-Saharan Africa. The authors were contacted and requested full articles by email when the article was not accessed from these sources.

Inclusion criteria

The study eligibility was determined using the following criteria:

Type of studies: Epidemiological study designs done in sub-Saharan Africa, including cohort, case-control, and retrospective follow-up, comparative cohort, and analytical cross-sectional studies, were included.

Intervention: This review include studies that evaluated EFV compared to NVP-containing regimens in a combination of three antiretroviral drugs. If cohorts report on other drugs in combination with EFV or NVP, or two NRTIs and a protease inhibitor, then only data for combination ART of two NRTIs with NVP or EFV were extracted.

Types of outcome measures: This review considered studies that included treatment failure or NNRTI switch as an outcome measure. Studies published between 2007 and 2016 in English language were included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies which were conducted among children (age < 15 years), published other than English language, and initiated ART other than NNRTI drugs were excluded from the review.

Study selection

The selection of studies from electronic databases was conducted in two stages: First decision was made based on titles and, where available, abstracts. Second, for studies that met the inclusion criteria, or in cases when a definite decision could not be made based on the title and/or abstract alone, the full paper was obtained for detailed assessment against the inclusion criteria. Two independent reviewers assessed study quality. The Kappa statistics was 0.86 which indicates the presence of good agreement between the reviewers. The papers were given to third reviewer for consensus while a discrepancy in decision process.

Quality assessment tools

Quality assessment of the included studies was also independently performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) [27] and Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale [28] by two independent reviewers. The first assessment tool consisted of nine questions. The later consisted of eight multiple-choice questions that addressed subject selection and comparability (of cases and controls in case-control studies, of cohorts in cohort studies) and the assessment of the outcome (in case-control studies) or exposure (in cohort studies). The number of possible answers per question ranged from two to five. High-quality responses earned a star, totaling up to nine stars.

Data extraction process

A standardized data collection form [29] was used to extract necessary data from the articles: the title of the study, first author’s last name, country where the study was conducted, study design, year of recruitment and follow-up, year of publication, sample size, study population, diagnosis and identification of treatment modification, average duration of follow-up (for cohort study), potential confounders that were adjusted for, main findings and quality assessment tools. Any data discrepancy was resolved by referring back to the original study.

Pretesting the data extraction tool

The selection process and data collection tool was pretested based on the inclusion criteria on five articles. It was aimed to check reliability of interpretation and classification of the studies appropriately and to ensure that all the relevant information was captured. The consistency of extracted data was assessed to reduce data extraction errors.

Outcome measures

Treatment failure was defined as either virologic, clinical, or immunological failure as per the definition of WHO ART guideline [8]. Studies which used composite outcome as their event was also defined as treatment failure. NNRTI substitution was defined as either NNRTI modification, regimen change, NNRTI resistance, or NNRTI discontinuation.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Heterogeneity among studies was examined using I-squared statistic. According to the test, I-square estimate greater than 50% was considered as indicative of moderate to high levels of heterogeneity [30]. Adjusted point estimates were extracted from individual studies and combined together to calculate the pooled estimates. The DerSimonian-Laird random effects method was used to incorporate an additional between study component to the estimate of variability [31, 32]. Subgroup analyses were done to explore differences in outcomes according to study outcomes. The qualitative and quantitative methods were used to present the data extracted from each study. Funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to check the presence of publication bias [33]. We plotted the effects by the inverse of its standard error. The symmetry of such plots was assessed both by using visually and with Egger’s test to see if the effect decreased with increasing sample size. Since graphical evaluation can be subjective, we conducted a regression asymmetry test as formal statistical tests for the presence of publication bias.

Meta-regression was conducted to investigate the impact of study characteristics on the study estimates of relative risk. The natural logarithm of the risk ratio was the dependent variable, and length of follow-up, median baseline CD4 cell counts, median age, proportion of female and year of publication were entered as explanatory variable. P value and 95% confidence interval were used to test statistical significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 12 software and Review Manager Version 5.3. Stata does not have built-in meta-analysis command; however, user written command called metan is available. Steps to install the command can be obtained from the book of Egger [34]. PRISMA 2009 checklist was used to keep the standard of the report (see Additional file 1).

Results

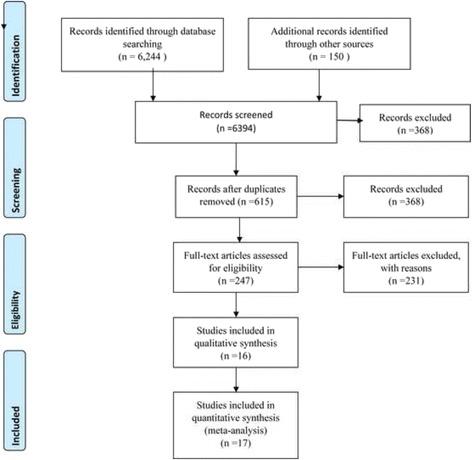

For inclusion in this review, studies were required to provide comparisons of NVP and EFV on the risk of long-term outcomes. A total of 6394 articles were identified in English language and human domain restrictions, of which, 5779 were rejected by looking only at the title of the research. The remaining 615 articles were further screened, and subsequently, 395 were considered irrelevant or duplicates. The abstracts of 238 articles were then evaluated independently. Of these, 158 records were excluded because of no comparison groups of the outcomes of interest, missing comparison of EFV versus NVP drugs and reviews and meta-analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram [35] is used to present stages of review process (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram of identification and selection of studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis

A study done on comparison between NVP and lopinavir-ritonavir [36] was excluded as it was not the interest of this review. Other six papers were excluded as the studies were conducted among children [37], conducted outside of sub-Saharan Africa, [38, 39, 40, 41], and systematic reviews and meta-analysis articles [20] were. Subsequently, of 79 full record articles, a total of 36 were eligible studies. Further, the full text of 36 articles were reviewed in detail, and 20 of them were excluded due to lack of sufficient information on sample size, design, and analysis. Study [42] used case-control design, and the sample size was small for both the cases and controls. It was not also clear how the size was determined. Study [43] had used cross-sectional study design, and the assessment tools might not evaluate the quality appropriately. Therefore, 16 studies were included in the quantitative synthesis out of which 17 outcome measures were identified for meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

Two independent reviewers assessed the articles prior to inclusion to maintain methodological validity using the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) [27]. The scores ranged from 5/9 to 8/9 in absolute number and 55.6 to 88.9% in percentage. In addition, Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale was used. The scores for each study ranged from 4 to 7 stars (from a total of 9).

Characteristics of included studies

All the 16 studies were conducted between 2007 and 2016. Sample size ranges from 167 [43] to 27,350 [44] patients. A total of 70,537 patients were included in all the studies. Of whom, 45,010 (63.8%) were females. The proportion of females ranges from 51 to 72%. Most of the patients, 42,039 (59.6%), were initiated with EFV-containing regimen. Overall, more females were initiated with NVP-containing regimens. The median follow-up time was 4 years (IQR 3–7). Study [45] had the longest follow-up time whereas studies [46, 47] had followed for shorter periods.

Almost half of the studies were from South Africa [43–49], the rest were from Kenya [50, 51], Ghana [10, 52], Nigeria [42], Zambia [50], Ethiopia [25, 53], and sub-Saharan Africa [54, 55]. Study [50] was a multicenter study (in Kenya, Zambia, and Thailand), and data from Kenya and Zambia were taken due to inclusion criteria. A total of 509 and 152 patients were included in Zambia and Kenya, respectively. With regard to the study design, most were retrospective cohort [9]. The minimum and maximum median age for the included studies were 32 (IQR 28–36) and 40 (IQR 35–47) years, respectively. In almost all studies, high median age corresponds to EFV-containing regimen at initiation. The median CD4 cell counts ranges from 67 (IQR 21–161) to 192 (IQR 112–324). The median CD4 cell count was smaller for patients who initiated with EFV-containing regimen. This might be due to the occurrence of different opportunistic infection among this group of patients, and EFV-containing regimen had no organ damage like hepatotoxicity and preferred for this group at large to maintain adherence [8]. Two studies [25, 43] did not report the median CD4 cell count at initiation. Only two studies [45, 55] reported the log transformed median viral load. NRTI backbones used differed between studies. Stavudine (d4T)/3TC were used in 13 studies, and three studies did not use this NRTI backbone at all. AZT/3TC was used in 14 studies, and two studies did not use this backbone at all. TDF/3TC was used less frequently, in only seven studies.

Most (11/16) of the studies used Cox proportional hazards model for the analysis and reported adjusted hazard ratio. Another two studies used stratified and random effect Cox-proportional models. About seven studies used second model (Conditional logistic regression, Poisson regression, mixed effect model and marginal structural models). Two of the studies further used sensitivity analysis. In general, with the statistical model used, most of the articles utilized appropriate analysis methods (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients on NVP and EFV by study design

| Author | Country | Design | Sample size | Follow-up Period | Female | Age Median ± IQR |

CD4 count Median ± IQR |

Viral load (log) Median ± IQR |

BMI Median ± IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stringer et al. [50] | Zambia and Kenya | Prospective Cohort | 509 152 |

4 years | 661 | Zambia 32 (28–36) Kenya 32 (28–36) |

148 (88–211) 147 (76.5–212.5) |

5.0 (4.4–5.4) 5.3 (4.8–5.9) |

19.7 (18.3–21.9) 19.9 (17.7–22.6) |

| Kwobah et al. [51] | Kenya | Case-control | 3233 | 5 years | 1992 | Case: 36.3(30.6–43.2) Control: 36.5(30.7–43.1) |

Case: 80 (32–177) Control: 194 (112–324) |

NA | NA |

| Nachega et al. [45] | South Africa | Cohort | 1817 | 10 years | 1771 | NVP: 33.2 (7.68) EFV: 36(8.0) |

NVP: 171(78–243) EFV: 136(58–216) |

NVP: 5.1(4.6–5.6) EFV: 5.2(4.7–5.7) |

NA |

| Boulle et al. (18, 48) | South Africa | Cohort | 2679 | 4 years | 1896 | 32(28–38) | 83(34–140) | 5.5(4.6–5.5) | NA |

| Shearer et al. ([47]) | South Africa | Cohort | 12,840 | 8 years | 7962 | EFV: 37.2(31.9–43.9) NVP: 33.0(28.4–39.1) |

EFV: 98(36–169) NVP: 100.5(42–160) |

NA | EFV: 21.7 (19.2_24.9) NVP: 22.0 (19.7_25.1) |

| Sarfo et al. [52] | Ghana | Retrospective Observational | 3990 | 7 years | 2717 | EFV: 40 (35–47) NVP: 35 (30–41) |

EFV: 127 (45–213) NVP: 140 (56–220) |

NA | EFV: 19.6 (17.4–22.3) NVP: 19.9 (17.6–22.9) |

| Shearer et al. [46] | South Africa | Cohort | 2385 | 1 year | 1485 | EFV: 37.8 (31.8–44.3) NVP: 33.1 (28.1–40.4) |

EFV: 132 (58–194) NVP: 132 (66–179) |

NA | EFV: 22.5 (19.7–25.9) NVP: 23.0 (20.2–25.6) |

| Barth et al. [49] | South Africa | Retrospective observational cohort | 735 | 2–4 years | 526 | Mean = 35.3 | 68 (20–140) | Mean = 4.9 | NA |

| Gsponer et al. [54] | Sub-Saharan Africa | Collaborative analysis | 2404 | 6 years | 1276 | Switched: 29 (25–33) Not switched: 29 (25–34) |

Switched: 77 (41–133) Not switched: 146 (82–232) |

NA | NA |

| Sarfo et al. [10] | Ghana | Retrospective cohort study | 3999 | 7 years | 2727 | 38 (32–45) | 132 (50–217) | NA | 19.8(17.5–22.7) |

| Keiser et al. [55] | Sub-Saharan Africa | Case control | 4281 | 5 years | 3022 | Switch: 35 (30–41) Not switch: 34 (30–40) |

Switch: 73 (23–133) Not switch: 67 (21–161) |

Switch: 5.0 (4.4–5.6) Not switch: 5.3 (4.6–5.8) |

NA |

| Anlay et al. [53] | Ethiopia | Retrospective follow-up | 410 | 5 years | 265 | 33.3 ± 8.7 | 162.5 (90.5–235.5) | NA | NA |

| van Zyl et al. [43] | South Africa | Retrospective | 167 | 4 years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Abah et al. [42] | Nigeria | Cohort | 6309 | 3 years | 4156 | 35 (30–42) | 154 (76–259) | NA | NA |

| Bock et al. [44] | South Africa | Multicentre cohort | 27,350 | 4 years | 16,828 | EFV: 35.8 (30.7–42.6) NVP: 31.1 (27.1–35.8) |

EFV: 107 (51–160) NVP: 132 (76–177) |

NA | NA |

| Tirfe et al. [25] | Ethiopia | Retrospective cohort study | 492 | 3 years | 289 | EFV: 35(10) NVP: 33(11) |

NA | NA | NA |

NA=Not Applicable

Treatment failure

In this review, treatment failure, the primary outcome of interest, was measured using clinical, virological, and immunological criteria. Studies [10, 25, 45–47, 49–51, 54, 55] defined treatment failure as their primary outcomes. A total of 30,069 patients were included in the ten studies. Of which, 19,584 (65%) were females. The majority, 17,950 (60%), were initiated with EFV-containing regimen. A total of 4842 patients experience treatment failure for both EFV and NVP drugs (2077 EFV and 2765 NVP). Study [45] defined treatment failure using two separate (consecutive or non-consecutive) measurements of viral load ≥ 400 copies/ml, or switch to another NNRTI or protease inhibitor after at least one such measurement. About 1822 (64.7%) patients were started on EFV-containing regimen. The two groups did not differ in viral load measurement; however, patients started on EFV had a significantly shorter time to virologic suppression. Subsequently, patients started on NVP were more likely to experience virologic failure (20.4 vs 13.8%). For study [50], the outcome was assessed at 48 weeks after initiating ART. Participant was considered as having failed at 48 week if she died prior to that time, or had a plasma viral load ≥ 400 copies/ml (confirmed with repeat testing) at either the 24- or 48-week study visits. The difference in failure rates between the NVP-exposed and unexposed groups was 6.9%. Study [51] was a case-control study in which case defined as adult at least one viral load measurement > 5000 copies/ml or meet the WHO 2006 immunological or clinical failure criteria [56]. Controls were those on non-failing first-line ART with a CD4 count > 400/ml within the last 12 months, at the time of case incidence. Patients who were either pregnant or co-infected with tuberculosis at the time of ART initiation were excluded. A total of 1084 cases were included with median time to ART failure of 37 months. Study [10] defined the outcome measure of treatment failure was a composite of death, clinical progression or discontinuation of NNRTI for any reason. A total of 3999 patients were involved from whom 2369 (59%) initiated by EFV-containing ART and 633 (26.7%) experienced at least one event.

The second outcome of interest was NNRTI substitution. Studies [10, 42, 44, 48, 53] defined NNRTI skin rash, NNRTI discontinuation, regimen change, NNRTI substitution, and regimen change as the outcome measure, respectively. Study [25] defined immunologic response, and study [49] patients retention as the outcome measure. In all studies, the initial NNRTI drug was substituted by another drug in the same regimen, hence defined NNRTI substitution as the outcome measure. Studies [10, 44, 46, 47] had outcome measure of death as an event. There were high number of death in patients who initiated with EFV, 208 (8.8%), than NVP, 110 (6.8%), containing regimen in study [10]. A total of 27,350 patients were included of whom 19,441 (71.1%) started EFV and 7909 (28.9%) started NVP treatment. At the end of the study period, 1593 (5.8%) patients died. Study [47] included 12,840 patients of whom 1061 died (8.3%) within the first 12 months on ART (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected results of the included studies

| Author | Outcomes | Intervention | Confounder adjusted | Main findings | Newcastle-Ottawa scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stringer et al. [50] | Treatment failure |

n

NVP = 355 n EFV = 523 |

Month on ART, CD4 cell count, viral load, WHO stage, age, Hgb, BMI, Weight, NNRTI, TB at baseline | -Month on ART, CD4 cell count, viral load, WHO stage, age, Hgb, and BMI were significantly associated factors. -In total, 724 women (82%) completed 48 weeks of follow-up on an NNRTI-containing regimen |

Selection 2 stars Comparability 1 star Outcome 2 stars |

| Kwobah et al. [51] | Treatment failure |

n

EFV = 427 n NVP = 2633 |

Education level, CD4 category, WHO stage, BMI, Hemoglobin, Adherence, disclosure, travel time, NNRTI, and NRTI | -No association between the choice of NNRTI used (Nevirapine or Efavirenz) and treatment failure -Low baseline CD4, AZT based NRTI, imperfect adherence are associated with first line ART failure |

Selection 3 stars Comparability 2 stars Outcome 1 star |

| Nachega et al. [45] | Virologic failure |

n

EFV = 212 n NVP = 103 |

Age, sex, race, baseline CD4, baseline VL, NRTI, year of ART, adherence | -Nevirapine was associated with greater risk of virologic failure compared to efavirenz -NNRTI, age, sex, baseline viral load, year on ART, and adherence were significantly associated with failure |

Selection 2 stars Comparability 2 stars Outcome 2 stars |

| Boulle et al. [18, 48] | NNRTI substitution |

n

EFV = 1612 n NVP = 1067 |

Weight, age, WHO stage per increment, CD4 Count, district | -Substantial difference in the tolerability of commonly used first line ART drugs. -Baseline weight, and Age, for NVP and Weigh and WHO stage for EFV |

Selection 2 stars Comparability 2 stars Outcome 2 stars |

| Shearer et al. [47] | Treatment failure |

n

EFV = 11,962 n NVP = 878 |

NNRTI, ART year, sex, age, baseline CD4, WHO stage, BMI, NRTI, baseline anemia | -Patients with NVP-are more likely to experience virologic failure -NNRTI, years of ART initiation, age, and baseline CD4 cell counts |

Selection 3 stars Comparability 2 stars Outcome 1 star |

| Sarfo et al. [10] | Composite endpoint |

n

EFV = 2369 n NVP = 1621 |

Sex, age, NNRTI, NRTI, Baseline CD4, baseline BMI, WHO stage, adherence | -Treatment outcomes were comparable whether EFV or NVP is used -There was a 36% lower risk of all-cause discontinuation of EFV compared with NVP -NRTI, age, baseline CD4 counts, BMI, WHO stage, and adherence were associated factors of treatment failure |

Selection 3 stars Comparability 2 stars Outcome 2 stars |

| Shearer et al. [46] | Treatment failure |

n

EFV = 2254 n NVP = 131 |

NNRTI, sex, age, baseline CD4, WHO stage, Anemia, BMI | -Given TDF as NRTI, Nevirapine has higher risk of treatment failure as compared to EFV. -Regimen, and Baseline CD4 cell counts were significantly associated with failure |

Selection 3 star Comparability 1 star Outcome 1 star |

| Barth et al. [49] | Treatment failure |

n

EFV = 426 n NVP = 309 |

Gender, age, BMI, Karnofsky score, CD4 counts, time since start ART, NNRTI, Occupation | -No difference between EFV and NVP in treatment failure −60% of patients showed virological failure; only few of them were switched to second-line treatment -Gender, mean BMI, and baseline CD4 counts were associated in the univariate |

Selection 2 star Comparability 1 star Outcome 2 star |

| Gsponer et al. 2012 [54] | Treatment failure |

n

EFV = 186 n NVP = 2218 |

Age, Sex, baseline CD4, WHO stage | -Mortality was lower among patients who switched compared to patients remaining on failing first-line ART -Current CD4 count was associated |

Selection 2 star Comparability 1 star Outcome 1 star |

| Sarfo et al. [10] | NNRTI Substitution |

n

EFV = 2378 n NVP = 1621 |

NNRTI, gender, age, BMI, WHO stage, CD4 counts, hepatitis B surface antigen status, ALT | -Patients starting nevirapine are more likely to develop rashes and then more likely to discontinue therapy than those starting efavirenz. -NNRTI, gender, and low baseline CD4 counts were associated factors |

Selection 3 star Comparability 2 star Outcome 1 star |

| Keiser et al. [55] | Treatment failure |

n

EFV = 1951 n NVP = 2325 |

Not controlled | -Compared to patients who remained on non-failing first-line therapy, mortality and loss from follow-up was higher in patients who switched, and substantially higher in patients who remained on failing first-line therapy | Selection 2 star Comparability 1 star Outcome 1 star |

| Anlay et al. [53] | NNRTI Substitution |

n

EFV = 289 n NVP = 121 |

Weight, WHO stage, TB on initial regimen, NRTI, NNRTI, Co-medication, and side effect | -There is no difference in regimen change between NVP and EFV -WHO stage, TB status, co-medication, and side effect were associated factors |

Selection 3 star Comparability 2 star Outcome 2 star |

| van Zyl et al. [43] | NNRTI resistance |

n

EFV = 82 n NVP = 85 |

Age, gender, ART regimen, most recent CD4 count, concurrent viral load, and genotypic resistance information | -Failure on NVP therapy may result in cross-resistance to ETV. NNRTI and estimated period of failure were associated |

Selection 2star Comparability 2 star Outcome 1 star |

| Abah et al. [42] | NNRT substitution |

n

EFV = 558 n NVP = 5751 |

Sex, age, HBV, CD4 count, WHO stage, NNRTI, NRTI | -Drug substitutions of efavirenz (EFV) were more likely than of nevirapine (NVP) -Age, greater immunosuppression, EFV compared to NVP, and drug toxicity were significant predictors |

Selection 2 star Comparability 1 star Outcome 2 star |

| Bock et al. [44] | NNRT substitution |

n

EFV = 19,441 n NVP = 7909 |

NNRTI, NRTI (AZT & D4T), gender, age, baseline CD4, WHO stage, TB treatment at baseline, year of ART initiation, level of care | -Superior efficacy of EFV compared with NVP for first-line ART -NNRTI, gender, year of initiation, and province were associated factors |

Selection 3 stars Comparability 2 stars Outcome 2 stars |

| Tirfe et al. [25] | Treatment failure |

n

EFV = 246 n NVP = 246 |

NNRTI, facility type, age, sex, marital status, education status, religion, NRTI, presence of OIs, eligibility criteria, WHO stage, functional status, BMI, provision of IPT, and baseline CD4 counts | -NVP and EFV based HAART regimens were effective and comparable, in term of immunological responses. -Gender, eligibility criteria, WHO stage, provision of IPT, and baseline CD4 counts were associated factors |

Selection 3 stars Comparability 2 stars Outcome 2 stars |

Meta-analysis results

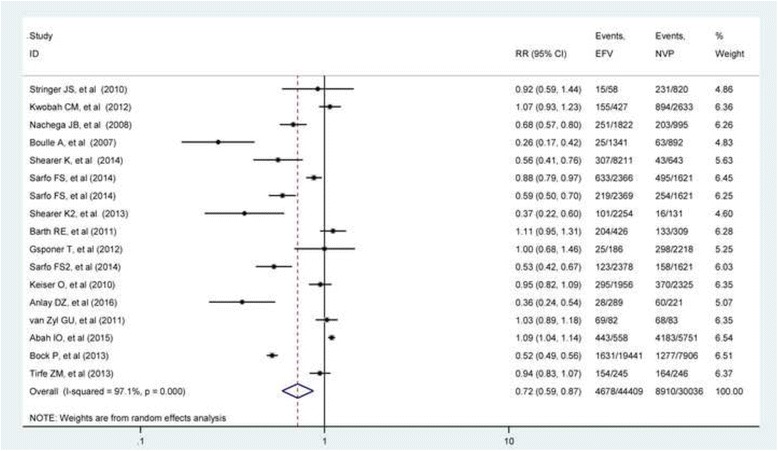

The overall analysis revealed presence of heterogeneity among the individual studies (I-squared = 97.1%) (Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis was performed based on the two outcomes of interest mentioned above.

Fig. 2.

Relative risk of composite outcome associated with the choice of NNRTI drugs regiment during ART initiation

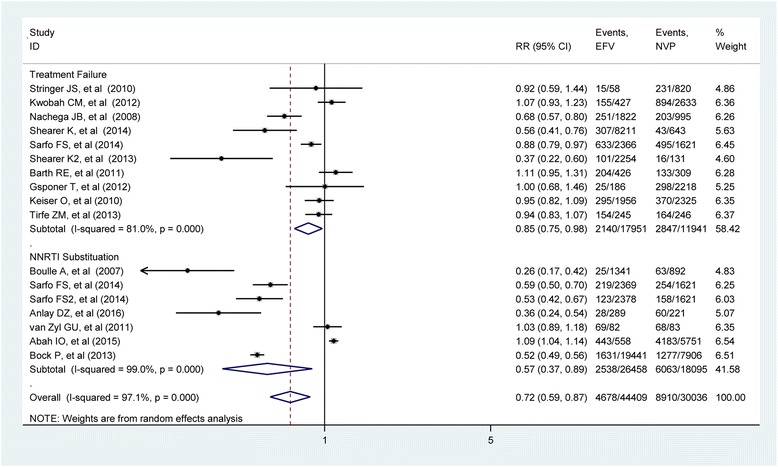

The first subgroup was treatment failure with ten studies [10, 25, 45–47, 50, 51, 54, 55, 57], and the second subgroup was NNRTI substitution which includes studies [10, 42–44, 48, 53]. The forest plot for treatment failure subgroup revealed that studies [25, 49, 51, 54, 55] were not statistically significant, but studies [10, 45–47] showed significant risk of treatment failure individually.

Heterogeneity among the studies within the subgroup was tested using I-squared statistics. The I-squared value for treatment failure subgroup was found to be 81.0% (p value < 0.0001) which indicated the presence of heterogeneity between studies. The weights of the studies were reported from random effect model which ranged from 0.31% to a maximum of 28.28%. The pooled estimate of risk ratio from random effect model was 0.85 (RR = 0.85; 95%CI 0.75–0.88) for EFV than NVP for treatment failure. For NNRTI substitution subgroup, almost all the studies were individually significant except study [43]. The I-squared value is 98.9% (p value = 0.0001) which indicates as there is high heterogeneity between studies. The weight of the studies ranges from 0.37 to 38.09%. The pooled estimate from random effect model was 0.57 (RR = 0.57; 95% CI 0.37–0.89) which is consistent with the estimate from the fixed effect model (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Relative risk of treatment failure and NNRTI substitution associated with the choice of NNRTI drugs regiment during ART initiation

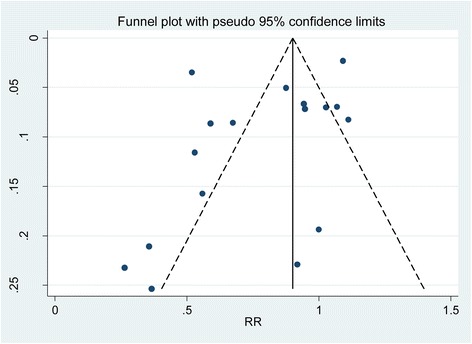

Evaluation for publication bias

One of the main problems in systematic review and meta-analysis is that not all studies carried out are published. Those which are published may be different from those which are not. Research with statistically significant results is more likely to be submitted and published than work with null or non-significant results. This could introduce bias during systematic review and meta-analysis. The presence of publication bias was assessed by funnel plots and tested using Egger’s test which is proposed by Egger et al. [33] to test for asymmetry of the funnel plot.

The funnel plot is assumed to be symmetric in the absence of research bias. The solid vertical line represents the summary estimate of the treatment effect. The diagonal lines representing the 95% confidence limit around the summary treatment effect. These show the expected distribution of studies in the absence of heterogeneity or of selection biases. It seems as there are more studies which lie to the left of the funnel plot. Egger’s test was performed for each subgroup. The test revealed that there was no significant bias for either of the outcome (overall test: intercept = − 2.217, 95% CI − 5.562; 1.128 and p value = 0.178) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot of effect estimates against standard error of log estimate

Meta regression was performed to determine whether there is a significant association between independent variables in the form of study versus the dependent variable. A regression model is constructed for covariates, length of follow-up, median CD4 cell counts, median age, and year of publication, and proportion of female. There was no significant relationship between any of the covariates and treatment failure which indicates that these covariates may not be the source of observed variability (Table 3). Bubble plot was plotted for selected covariates (see Additional file 2).

Table 3.

Parameter estimates of meta-regression

| Covariate | Estimate | S.E | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of follow-up | − 0.0138 | 0.0666 | (− 0.1322–0.1046) |

| Median CD4 count | − 0.0034 | 0.0066 | (− 0.0150–0.0079) |

| Median age | 0.0415 | 0.0503 | (− 0.1013–0.0755) |

| Year of publication | 0.0637 | 0.0815 | (− 0.1736–0.0980) |

| Female proportion | − 0.5305 | 1.4575 | (− 3.6792–2.6183) |

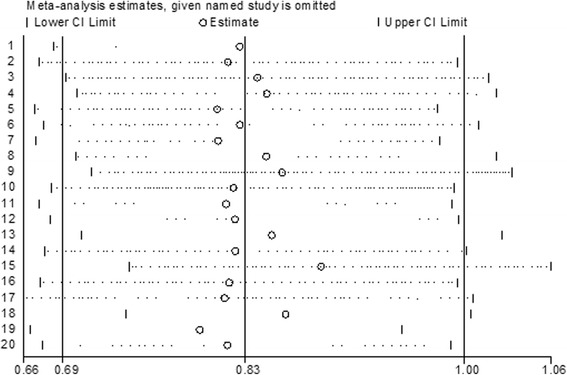

Sensitivity analysis has been performed to identify study which has more influence on the estimates. The plot visually provides estimate with 95% confidence interval, naming the omitted study on the left margin. The lower and upper confidence interval limits were presented for the estimates. The sensitivity analysis revealed that there is no single study affecting the estimate too much. Exclusion of [53] seems influential, but the effect is not statistically significant (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Plot of sensitivity analysis to assessing the influence of individual study

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis attempted to assess the individual and pooled estimate of the choice of NNRTI drugs on treatment failure and NNRTI switch in resource-poor settings. A total of 16 observational studies were found which compares EFV versus NVP, out of which, 17 outcome measures were identified in two groups.

The findings revealed that initiation of ART with EFV-containing regimen is associated with a reduced risk of treatment failure (RR = 0.85, 95%CI 0.75–0.98) as compared to NVP-containing regimen in resource-limited settings. This finding was consistent across four of the ten individual studies. This is in line with previous meta-analysis [20] conducted from ten RCTs and 24 observational studies which concluded that EFV-based first line ART regimen is significantly less likely to lead to virologic failure compared to NVP-based ART regimen. This might be due to the hepatotoxic nature of NVP which may lead to poor adherence which might further resulted in treatment failure.

In the 2NN group study [58], there was no any evidence that EFV is superior to NVP twice daily in terms of treatment failure. A Cochrane review of seven randomized clinical trials [59] demonstrated that the two drugs provided comparable levels of viral suppression in patients infected with HIV when combined with two NRTIs. In a non-randomized longitudinal cohort study conducted in India [39], equivalent immunological response was observed among NVP and EFV-based ART.

The risk ratio of NNRTI switch reduced by 0.57 (95% CI 0.37–0.89) times for patients who initiated with EFV than NVP. This finding is consistent with a multicenter randomized non-inferiority trial [60] in which the switching rate is higher among patients who initiated with NVP than EFV. This finding is also consistent with previous meta-analyses [21] which revealed that adults on NVP were two times more likely to discontinue treatment due to any adverse event compared to patients on EFV. Another meta-analysis on five randomized clinical trials and four retrospective clinical trials [61] revealed that the discontinuation rate was high among those who initiated with NVP than EFV which is consistent with this review. Similar finding was reported by meta-analysis of 26 RCTs [62] in which the discontinuation rate was lower among those who initiated with EFV than NVP-containing regimen.

The source of heterogeneity was assessed using meta-regression. Covariates length of follow-up, median CD4 cell counts, median age, and year of publication were included in the regression model. The log relative risk of treatment failure was not a significant difference among length of follow-up, median CD4 cell counts, median age, or year of publication. This might be due to the small number of included studies in the analysis. Sensitivity analysis also revealed that there is no single study which influences the pooled estimate.

These results need to be interpreted with caution due to limitations. Although a lot of efforts have been made to find more studies, still there were few studies which satisfied the inclusion criteria. The analysis was limited to only articles published in English language; the evidence may not be sufficiently robust to determine the comparative effectiveness of EFV and NVP due to the size of included studies. In addition, the analysis included articles with different definitions of treatment failure and different lengths of follow-up. The reviewed articles have also differences in study design, the type of statistical methods, and the variables included in the analysis. These variations may have resulted in selection bias or low statistical power, thus hindering results. Most of our analyses detected heterogeneity between effect estimates obtained across studies. DerSimonian and Laird random effect model was used to determine the pooled effect size [32, 33]. However, the source of variation might not be real heterogeneity rather within study differences which may introduce bias on the pooled effect size.

Conclusion

The finding of this review showed that initiation of ART with EFV-containing regimen has reduced risk of treatment failure as compared to NVP-containing regimen. In addition, the patients who initiated with EFV are less likely to switch than those with NVP. In contrast, there was about 50% increased risk of death in patients who initiated with EFV as compared to NVP-containing regimens. Even though EFV is more expensive to afford for resource-poor settings, initiating the patient with EFV-containing regimen could be supreme important.

Additional files

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 checklist. The PRISMA 2009 checklist which was used to standardize the review. (PDF 589 kb)

Bubble plot with fitted meta-regression line depicting the relationship between the risk of composite outcomes and baseline covariates (proportion of female, baseline CD4 cell counts and follow up period). Fig. S1. Bubble plots of the fitted meta-regression with proportion of female, baseline CD4 counts and follow-up time. (PDF 177 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge University of Gondar, College of Medicine and Health Sciences for the opportunity given to conduct this review.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All the required data are available in the main paper.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- ART

Antiretroviral therapy

- AZT

Zidovudine

- CI

Confidence intervals

- CNS

Central nervous system

- EFV

Efavirenz

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- NNRTIs

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- NRTIs

Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- NVP

Nevirapine

- OR

Odds ratio

- PIs

Protease inhibitors

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

TAA, AW, YK, KA, AK, and ZS conceived and designed concept for the review. TAA, AW, YK, KA, AK, and ZS approved the proposal with some revisions. TAA and KA performed the search of articles. TAA, AW, YK, KA, AK, and ZS synthesized and analyzed the data. TAA, AW, YK, KA, AK, and ZS wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13643-017-0567-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Tadesse Awoke Ayele, Email: tawoke7@gmail.com.

Alemayehu Worku, Email: alemayehuwy@yahoo.com.

Yigzaw Kebede, Email: gkyigzaw@yahoo.com.

Kassahun Alemu, Email: kassalemu@gmail.com.

Adetayo Kasim, Email: a.s.kasim@durham.ac.uk.

Ziv Shkedy, Email: ziv.shkedy@uhasselt.be.

References

- 1.WHO . Global Health Observatory (GHO) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stover J, Johnson P, Zaba B, Zwahlen M, Dabis F, Ekpini RE. The Spectrum projection package: improvements in estimating mortality, ART needs, PMTCT impact and uncertainty bounds. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84(Suppl I):24–30. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mekuria LA, Nieuwkerk PT, Yalew AW, Sprangers MA, Prins JM. High level of virological suppression among HIV-infected adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in Addis Ababa. Ethiopia. Antivir Ther. 2016;21:385–96. doi: 10.3851/IMP3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet (London, England) 2006;367(9513):817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson I, Togun O, de Silva T, Oko F, Rowland-Jones S, Jaye A, et al. Mortality and immunovirological outcomes on antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 and HIV-2-infected individuals in the Gambia. AIDS (London, England) 2011;25(17):2167–2175. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834c4adb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, Modur SP, Althoff KN. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AIDSinfo . Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO . Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents 2010 revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blas-García A, Apostolova N, Esplugues JV. Future perspectives in NNRTI-based therapy: bases for understanding their toxicity: InTech. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarfo FS, Sarfo MA, Kasim A, Phillips R, Booth M, Chadwick D. Long-term effectiveness of first-line non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based antiretroviral therapy in Ghana. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(1):254–261. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiguba R, Byakika-Tusiime J, Karamagi C, Ssali F, Mugyenyi P, Katabira E. Discontinuation and modification of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected Ugandans: prevalence and associated factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(2):218–223. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31805d8ae3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassan AS, Nabwera HM, Mwaringa SM, Obonyo CA, Sanders EJ, de Wit TFR, et al. HIV-1 virologic failure and acquired drug resistance among first-line antiretroviral experienced adults at a rural HIV clinic in coastal Kenya: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther. 2014;11(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adeyinka DA, Ogunniyi A. Predictors of clinical failure in HIV/AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy in a resource limited setting, Nigeria: a comparative study. HIV & AIDS Rev. 2012;11(1):20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.hivar.2011.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization, UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update: December 2009: Geneva: WHO Regional Office Europe; 2009.

- 15.Luma HN, Choukem S, Temfack E, Ashuntantang G, Joko H, Koulla-Shiro S. Adverse drug reactions of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in HIV infected patients at the General Hospital, Douala, Cameroon: a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;12(1):87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barry O, Powell J, Renner L, Bonney EY, Prin M, Ampofo W, et al. Effectiveness of first-line antiretroviral therapy and correlates of longitudinal changes in CD4 and viral load among HIV-infected children in Ghana. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):476. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanne IM, Westreich D, Macphail AP, Rubel D, Majuba P, Rie A. Long term outcomes of antiretroviral therapy in a large HIV/AIDS care clinic in urban South Africa: a prospective cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulle A, Orrell C, Kaplan R, Van Cutsem G, McNally M, Hilderbrand K, et al. Substitutions due to antiretroviral toxicity or contraindication in the first 3 years of antiretroviral therapy in a large South African cohort. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(5):753–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Woldemedhin B, Wabe NT. The reason for regimen change among HIV/AIDS patients initiated on first line highly active antiretroviral therapy in southern Ethiopia. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4(1):19–23. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.92898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pillay P, Ford N, Shubber Z, Ferrand RA. Outcomes for efavirenz versus nevirapine-containing regimens for treatment of HIV-1 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shubber Z, Calmy A, Andrieux-Meyer I, Vitoria M, Renaud-Théry F, Shaffer N, et al. Adverse events associated with nevirapine and efavirenz-based first-line antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England) 2013;27(9):1403–1412. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835f1db0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swaminathan S, Padmapriyadarsini C, Venkatesan P, Narendran G, Ramesh Kumar S, Iliayas S, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily nevirapine- or efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy in HIV-associated tuberculosis: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):716–724. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takuva S, Evans D, Zuma K, Okello V, Louwagie G. Comparative durability of nevirapine versus efavirenz in first-line regimens during the first year of initiating antiretroviral therapy among Swaziland HIV-infected adults. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15(1):5. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.5.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Dijk JH, Sutcliffe CG, Hamangaba F, Bositis C, Watson DC, Moss WJ. Effectiveness of efavirenz-based regimens in young HIV-infected children treated for tuberculosis: a treatment option for resource-limited settings. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tirfe ZM, Ahmed TA, Tedla NB, Debere MK, Alamdo AG. Immunological responses of HIV/AIDS patients treated with nevirapine versus efavirenz based highly active anti-retroviral therapy in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Health. 2013;05(09):1502–1508. doi: 10.4236/health.2013.59204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandhi D, Ailawadi P. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2014;35(1):1–11. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.132399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.JBI . Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2014 edition. Australia: The University of Adelaide; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li T, Swaroop Vedula S, Hadar N, Parkin C, Lau J, Dickersin K. Innovations in data collection, management, and archiving for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:287–294. doi: 10.7326/M14-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed 20 June 2016.

- 31.Jackson D, Bowden J, Baker R. How does the DerSimonian and Laird procedure for random effects meta-analysis compare with its more efficient but harder to compute counterparts? J Stat Plan Inference. 2010;140(4):961–970. doi: 10.1016/j.jspi.2009.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp. Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman D. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

- 35.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clumeck N, Mwamba C, Kabeya K, Matanda S, Vaira D, Necsoi C, et al. First-line antiretroviral therapy with nevirapine versus lopinavir-ritonavir based regimens in a resource-limited setting. AIDS (London, England) 2014;28(8):1143–1153. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowenthal ED, Ellenberg JH, Machine E, Sagdeo A, Boiditswe S, Steenhoff AP, et al. Association between efavirenz-based compared with nevirapine-based antiretroviral regimens and virological failure in HIV-infected children. JAMA. 2013;309(17):1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinha S, Raghunandan P, Chandrashekhar R, Sharma SK, Kumar S, Dhooria S, et al. Nevirapine versus efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy regimens in antiretroviral-naive patients with HIV and tuberculosis infections in India: a pilot study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel A, Pujari S, Patel K, Patel J, Shah N, Patel B, et al. Nevirapine versus efavirenz based antiretroviral treatment in naive Indian patients: comparison of effectiveness in clinical cohort. JAPI. 2006;54:915–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boettiger DC, Sudjaritruk T, Nallusamy R, Lumbiganon P, Rungmaitree S, Hansudewechakul R, et al. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in perinatally HIV-infected, treatment-naive adolescents in Asia. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(4):451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.López de Castilla D, Verdonck K, Otero L, Iglesias D, Echevarría J, Lut L, et al. Predictors of CD4+ cell count response and of adverse outcome among HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in a public hospital in Peru. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(3):325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abah IO, Darin KM, Ebonyi AO, Ugoagwu P, Ojeh VB, Nasir N, et al. Patterns and predictors of first-line antiretroviral therapy modification in HIV-1-infected adults in a large urban outpatient cohort in Nigeria. J Int Assoc Prov AIDS Care. 2015;14(4):348–354. doi: 10.1177/2325957414565508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Zyl GU, van der Merwe L, Claassen M, Zeier M, Preiser W. Antiretroviral resistance patterns and factors associated with resistance in adult patients failing NNRTI-based regimens in the western cape, South Africa. J Med Virol. 2011;83(10):1764–1769. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bock P, Fatti G, Grimwood A. Comparing the effectiveness of efavirenz and nevirapine for first-line antiretroviral therapy in a South African multicentre cohort. Int Health. 2013;5(2):132–138. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/iht002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, Gallant JE, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, et al. Efavirenz versus nevirapine-based initial treatment of HIV infection: clinical and virological outcomes in Southern African adults. AIDS (London, England) 2008;22(16):2117–2125. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328310407e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shearer K, Fox MP, Maskew M, Berhanu R, Long L, Sanne I. The impact of choice of NNRTI on short-term treatment outcomes among HIV-infected patients prescribed tenofovir and lamivudine in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shearer K, Brennan AT, Maskew M, Long L, Berhanu R, Sanne I, et al. The relation between efavirenz versus nevirapine and virologic failure in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19065. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boulle A, Orrel C, Kaplan R, Van Cutsem G, McNally M, Hilderbrand K, et al. Substitutions due to antiretroviral toxicity or contraindication in the first 3 years of antiretroviral therapy in a large South African cohort. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(5):753–760. doi: 10.1177/135965350701200508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barth RE, Tempelman HA, Moraba R, Hoepelman AI. Long-term outcome of an HIV-treatment programme in rural Africa: viral suppression despite early mortality. AIDS Res Treat. 2011;2011:434375. doi: 10.1155/2011/434375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stringer JS, McConnell MS, Kiarie J, Bolu O, Anekthananon T, Jariyasethpong T, et al. Effectiveness of non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in women previously exposed to a single intrapartum dose of nevirapine: a multi-country, prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwobah CM, Mwangi AW, Koech JK, Simiyu GN, Siika AM. Factors associated with first-line antiretroviral therapy failure amongst HIV-infected African patients: a case-control study. World J AIDS. 2012;02(04):271–278. doi: 10.4236/wja.2012.24036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarfo FS, Sarfo MA, Norman B, Phillips R, Chadwick D. Incidence and determinants of nevirapine and efavirenz-related skin rashes in West Africans: nevirapine’s epitaph? PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anlay DZ, Alemayehu ZA, Dachew BA. Rate of initial highly active anti-retroviral therapy regimen change and its predictors among adult HIV patients at University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective follow up study. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13:10. doi: 10.1186/s12981-016-0095-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gsponer T, Petersen M, Egger M, Phiri S, Maathuis MH, Boulle A, et al. The causal effect of switching to second-line ART in programmes without access to routine viral load monitoring. AIDS (London, England) 2012;26(1):57–65. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834e1b5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keiser O, Tweya H, Braitstein P, Dabis F, MacPhail P, Boulle A, et al. Mortality after failure of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(2):251–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization . Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach—2006 revision. 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhatt NB, Baudin E, Meggi B, da Silva C, Barrail-Tran A, Furlan V, et al. Nevirapine or efavirenz for tuberculosis and HIV coinfected patients: exposure and virological failure relationship. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(1):225–232. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Leth F, Phanuphak P, Ruxrungtham K, Baraldi E, Miller S, Gazzard B, Cahn P, et al. Comparison of first-line antiretroviral therapy with regimens including nevirapine, efavirenz, or both drugs, plus stavudine and lamivudine: a randomised open-label trial, the 2NN Study. Lancet (London, England) 2004;363:1253–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15997-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mbuagbaw LC, Irlam JH, Spaulding A, Rutherford GW, Siegfried N. Efavirenz or nevirapine in three-drug combination therapy with two nucleoside-reverse transcriptase inhibitors for initial treatment of HIV infection in antiretroviral-naïve individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;8(12):CD004246. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004246.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonnet M, Bhatt N, Baudin E, Silva C, Michon C, Taburet AM, et al. Nevirapine versus efavirenz for patients co-infected with HIV and tuberculosis: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(4):303–312. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang HY, Zhang MN, Chen HJ, Yang Y, Deng M, Ruan B. Nevirapine versus efavirenz for patients co-infected with HIV and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;25:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kryst J, Kawalec P, Pilc A. Efavirenz-based regimens in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0124279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 checklist. The PRISMA 2009 checklist which was used to standardize the review. (PDF 589 kb)

Bubble plot with fitted meta-regression line depicting the relationship between the risk of composite outcomes and baseline covariates (proportion of female, baseline CD4 cell counts and follow up period). Fig. S1. Bubble plots of the fitted meta-regression with proportion of female, baseline CD4 counts and follow-up time. (PDF 177 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All the required data are available in the main paper.