Abstract

A rare isolated double orifice mitral valve (DOMV) was diagnosed in a 77-year-old male patient, being assessed for surgical repair of the ascending aorta. This is a rare congenital abnormality, usually discovered as an incidental finding during investigation of other congenital heart defects. This case shows that a detailed assessment of all cardiac structures is necessary, not only in young patients, but also in the elderly population, to minimise the under-diagnosis of such rare anomalies. The use of 3D transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has an increasingly significant role in establishing the diagnosis and extending the morphological and functional understanding of the anomaly.

Learning points:

Thoroughly assessing all cardiac structures, in accordance with the minimum dataset guidelines for transthoracic echocardiography, ensures not only a comprehensive assessment of the primary indication for the scan, but also improves the detection of concomitant and otherwise unknown lesions.

Despite falling under the category of congenital heart defects, several rare anomalies such as DOMV can be present in elderly patients, and the adult echocardiographer should have appropriate knowledge and awareness for detecting these conditions.

3D TTE provides a comprehensive assessment of the morphology of DOMV, over and above the information obtained by 2D imaging.

Keywords: double-orifice mitral valve, 3D transthoracic echocardiography, congenital heart defects

Background

Due to its common association with other congenital heart defects, DOMV is usually discovered in childhood or early adolescence (1). This case highlights the possibility of detecting congenital mitral valve anomalies, not only in the younger population, but also as an incidental finding in elderly patients referred for other indications. Under such circumstances, subtle congenital abnormalities, may be missed, particularly in the absence of a comprehensive evaluation and appropriate awareness of the condition. The fact that an isolated and asymptomatic DOMV, as the one presented, can remain undiagnosed, makes its incidence and prognosis in adulthood unknown. Once the anomaly has been recognised, having the equipment and technical ability to perform 3D analysis of the valve can prove extremely useful in identifying the morphology type (described below), and providing further anatomical and functional information, such as orifice size and its spatial relationship.

Case presentation

We present here a case of a 77-year-old man who has been under cardiology review for hypertension, chronic atrial fibrillation and minor coronary artery disease. An MRI scan in 2015 showed dilatation of the aortic root (48 mm) and ascending aorta (56 mm). He was then referred to the cardiothoracic surgical team, who recommended replacement of the aortic root and ascending aorta to prevent aortic rupture or dissection.

Investigation

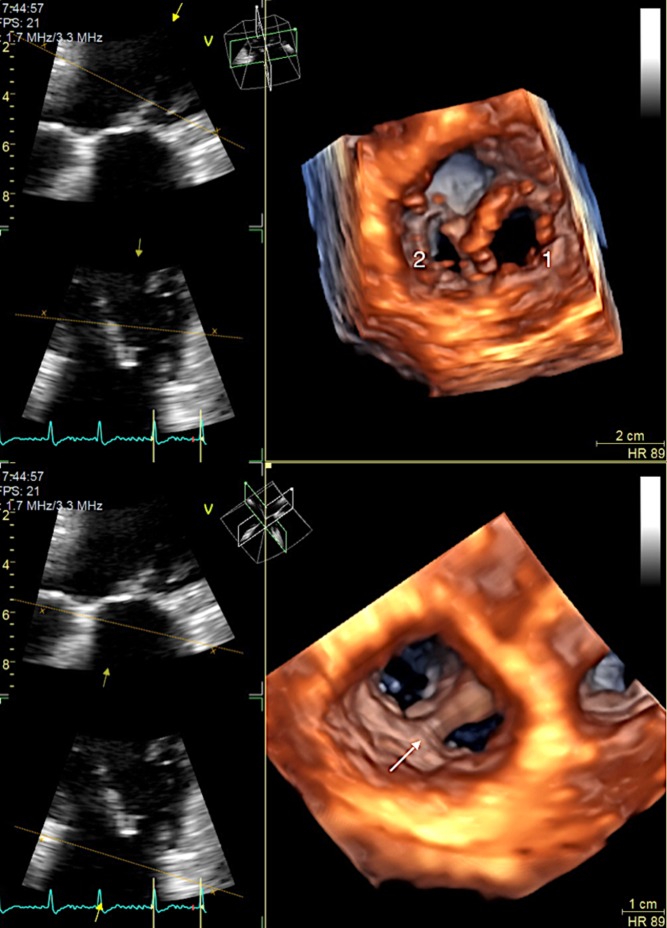

Upon performing a standard pre-operative TTE, a normally functioning isolated DOMV of the complete bridge type, was incidentally detected. The morphology was that of a left atrioventricular valve with a single annulus and a central ridge of fibrous tissue connecting the two leaflets and dividing the inlet into two orifices. The functional effect was limited to two trivial jets of regurgitation, one from each orifice, and no stenosis. Three-dimensional TTE was used to better delineate and study the anomaly. Visualisation from both the ventricular and atrial surface of the mitral valve confirmed the diagnosis and illustrated the relative dimensions of the orifices, showing a larger anterolateral orifice (Fig. 1 and Videos 1 and 2); in 85% of reported cases, the orifices are asymmetrical (2, 3).

TTE 3D zoom mode acquisition of a double orifice mitral valve, imaged from left atrial surface (‘surgeon’s view’). View Video 1 at http://movie-usa.glencoesoftware.com/video/10.1530/ERP-17-0023/video-1.

Download Video 1 (319.6KB, mov)

TTE 3D zoom mode acquisition of a double orifice mitral valve, imaged from left ventricle surface. View Video 2 at http://movie-usa.glencoesoftware.com/video/10.1530/ERP-17-0023/video-2.

Download Video 2 (303.3KB, mov)

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiographic images of the mitral valve from the left ventricle (above) and left atrial ‘surgeon’s view’ (below). Evidence of two asymmetrical inlet orifices, a bigger anterolateral (1) and a smaller posteromedial (2) mitral orifices, separated by a central bridge of fibrous tissue (arrow), and with unrestricted opening.

Treatment and outcome

Despite the morphological abnormality of the mitral valve, active intervention was not indicated as normal valve function was preserved with no evidence of significant obstruction or regurgitation. Patients with a significantly dysfunctional DOMV may present with heart failure requiring initial medical therapy. In a severely stenotic DOMV, percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty has been described as the initial method of choice in the absence of significant regurgitation; if technically feasible, dilatation of both orifices is attempted (4). However, experience is limited and the inherent risk of the procedure with the potential for traumatic leaflet damage need to be borne in mind. Other morphological features that may favour a percutaneous approach over surgical treatment have not been described in any detail. In the presence of significant mitral regurgitation, surgical repair or replacement should be considered in symptomatic patients (5). Since, in most cases, the dividing bridge is composed of mitral and chordal tissue, surgical transection of the dividing bridge is not advised, in order to avoid iatrogenic mitral regurgitation (6). The risk of infective endocarditis in isolated DOMV is extremely low, with only one reported case of this combination (7). In accordance with recent guidelines, patients with DOMV do not require antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis (8).

Discussion

The first case of DOMV was reported in 1876 by Greenfield (2, 3) and since then large autopsy data have shown that DOMV can occur in 1% of all congenital abnormalities, most commonly associated with atrioventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus and coarctation of the aorta (6). Ours was an unusual case of isolated DOMV in an elderly individual. Extensive review of multiple cases has resulted in the identification of different DOMV morphology types: (1) eccentric or hole type is the most common presentation, consisting of a small accessory orifice located in essentially normal leaflets, at the posteromedial or anterolateral commissure, visible only at the mid-leaflet level and disappearing on tilting up or down; (2) complete bridge type, in which a central bridge of fibrous or abnormal leaflet tissue connects the two leaflets of the mitral valve, creating two equal or unequal sized openings, visible from the leaflets edge, all the way through the valve ring; (3) incomplete bridge type, in which a small strand of tissue connects the anterior and posterior leaflets at the edge, but with normal appearance at the base of the leaflets and annulus (2, 6); (4) duplicate mitral valve type, with two separate mitral valve annuli, each with its own set of leaflets and sub-valvular apparatus (9).

Recognition of the different types of DOMV with the use of echocardiography has been accomplished by carefully examining the different levels of the mitral valve apparatus in the parasternal short axis view, slowly tilting from the leaflet edge down to the annulus of the valve. However, this process can be significantly improved with the use of 3D TTE. Obtaining a single or multi-beat zoomed volume of the mitral valve apparatus is a reasonably simple procedure, which later allows for post-processing where the imaging plane can be easily aligned and manipulated to visualise the different structures with precise translation through the valve. The images shown were obtained from a single beat acquisition, as this avoided stitching artefact of multiple beats, in view of the patients chronic atrial fibrillation. This proves that the presence of arrhythmias should not hinder the use of 3D imaging, as long as the frame rate is adequately optimised. However, despite optimising the settings, a satisfactory 3D colour flow image was not achievable in this case because of a marked reduction in frame rate during single beat acquisition.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this case report.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Patient consent

Patient consent was obtained for the current publication.

References

- 1.Kron J, Standerfer RJ, Starr A. 1986. Severe mitral regurgitation in a woman with a double orifice mitral valve. British Heart Journal 55 109–111. ( 10.1136/hrt.55.1.109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob J, Sunil TC, Bobby John. 2003. Double-orifice mitral valve. Indian Heart Journal 55 279–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anwar A, McGhie J, Meijboom F, ten Cate F. 2008. Double orifice mitral valve by real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. European Journal of Echocardiography 9 731–732. ( 10.1093/ejechocard/jen149) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McElhinney DB, Sherwood MC, Keane JF, del Nido PJ, Almond CS, Lock JE. 2005. Current management of severe congenital mitral stenosis: outcomes of transcatheter and surgical therapy in 108 infants and children. Circulation 112 707–714. ( 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.500207) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartas G. 2014. Double orifice mitral valve. eMedicine article 897322. (available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/897322-treatment#showall). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baño-Rodrigo A, Van Praagh S, Trowitzsch E, Van Praagh R. 1988. Double-orifice mitral valve: a study of 27 postmortem cases with developmental, diagnostic and surgical considerations. American Journal of Cardiology 61 152–160. ( 10.1016/0002-9149(88)91322-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedeir K, Ramlawi B. 2016. Is a double orifice valve at an increased risk for endocarditis? European Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery 50 389 ( 10.1093/ejcts/ezw046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson W Taubert KA Gewitz M Lockhart PB Baddour LM Levison M Bolger A, Cabell CH, Takahashi M, Baltimore RS et al. 2007. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation 116 1736–1754. ( 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183095) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wójcik A, Klisiewicz A, Szymański P, Różański J, Hoffman P. 2011. Double-orifice mitral valve – echocardiographic findings. Kardiologia Polska 2 139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TTE 3D zoom mode acquisition of a double orifice mitral valve, imaged from left atrial surface (‘surgeon’s view’). View Video 1 at http://movie-usa.glencoesoftware.com/video/10.1530/ERP-17-0023/video-1.

Download Video 1 (319.6KB, mov)

TTE 3D zoom mode acquisition of a double orifice mitral valve, imaged from left ventricle surface. View Video 2 at http://movie-usa.glencoesoftware.com/video/10.1530/ERP-17-0023/video-2.

Download Video 2 (303.3KB, mov)

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a