Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Abstract

Purpose

Patients benefit from receiving cancer treatment closer to home when possible and at high-volume regional centers when specialized care is required. The purpose of this analysis was to estimate the economic impact of retaining more patients in-state for cancer clinical trials and care, which might offset some of the costs of establishing broader cancer trial and treatment networks.

Method

Kansas Cancer Registry data were used to estimate the number of patients retained in-state for cancer care following the expansion of local cancer clinical trial options through the Midwest Cancer Alliance based at the University of Kansas Medical Center. The 2014 economic impact of this enhanced local clinical trial network was estimated in four parts: Medical spending was estimated on the basis of National Cancer Institute cost-of-care estimates. Household travel cost savings were estimated as the difference between in-state and out-of-state travel costs. Trial-related grant income was calculated from administrative records. Indirect and induced economic benefits to the state were estimated using an economic impact model.

Results

The authors estimated that the enhanced local cancer clinical trial network resulted in approximately $6.9 million in additional economic activity in the state in 2014, or $362,000 per patient retained in-state. This estimate includes $3.6 million in direct spending and $3.3 million in indirect economic activity. The enhanced trial network also resulted in 45 additional jobs.

Conclusions

Retaining patients in-state for cancer care and clinical trial participation allows patients to remain closer to home for care and enhances the state economy.

Patients who travel greater distances to receive cancer care report more emotional and financial stress,1 have lower treatment take-up,2 receive less appropriate treatment,3 and have lower quality of life3 than those who travel shorter distances. However, travel to regional care centers might be optimal for certain types of care and procedures. Studies consistently suggest increased survival rates for patients undergoing surgical procedures at high-volume regional centers versus lower-volume hospitals.4–8 Providing exceptional patient care—a key component of the mission of academic medical centers (AMCs)—requires balancing preferences for care close to home with the need for high-volume care in specialized services.

Achieving this balance can be challenging for AMCs that serve as regional care centers for varied in-state populations, such as patients from both isolated rural communities and urban areas. The strategy of one Midwestern AMC, the University of Kansas (KU) Medical Center, is to provide care close to patients when possible through telemedicine and through partnerships with local providers and to build capacity as a regional center for highly specialized care. Since 2010, the KU Cancer Center (KUCC) at the KU Medical Center has served as the headquarters for the Midwest Cancer Alliance (MCA), which offers cancer clinical trials at locations across Kansas through a network of 12 partner organizations.

Providing robust local clinical trial services requires a strong commitment from local providers and often from state and local governments in the form of financing.9 Building capacity as a regional care center also requires substantial investment and sufficient patient demand.10 However, the federal and many state governments are running budget deficits. Further, financial support for cancer clinical trial networks is likely to shift more toward the states in the coming years, because the federal government has replaced funding for cancer clinical trials through the Community Clinical Oncology Program and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Cancer Centers Program with the NCI Community Oncology Research Program and consolidated National Clinical Trials Network, which represent an overall decrease in budget.11,12 In the case of the MCA, the development of more robust in-state cancer treatment options was supported by philanthropy and the Johnson County Education Research Triangle sales tax.

Although making the case for robust in-state cancer clinical trial options begins with the patients, it is important to understand the economic impacts of these investments on states as policy makers consider how to allocate funding for competing needs. In this study, we used the recent expansion of local cancer clinical trial treatment options in Kansas through the MCA to estimate changes in economic activity. The economic impacts occur when fewer patients seek treatment in out-of-state cancer clinical trials and more medical spending dollars remain in their state of residence. Increases in medical spending can lead to more jobs and to increased tax revenue, which partially offsets the public and private costs of funding in-state treatment networks. In the sections below, we outline our main assumptions and calculations and present our economic impact estimates.

Method

Using Kansas Cancer Registry data, we calculated that following the expansion of in-state cancer clinical trial options through the MCA in 2010, there was a nearly 20% reduction in the percentage of newly diagnosed Kansas cancer patients receiving some or all of their cancer care outside the state in 2010–2011 as compared with 2007–2008. Of note, the clinical trial expansion occurred prior to the NCI designation for KUCC in 2014, which allowed us to isolate the estimated effects of trial expansion from changes in patient demand associated with the designation.

We estimated the 2014 economic impact of local clinical trial spending in four main categories: medical spending, travel cost savings, grant revenue, and indirect/induced economic effects (often called multipliers). All estimates are presented in annual 2014 U.S. dollars and represent changes in spending in 2014 that are attributable to increased in-state clinical trial participation and cancer care. The study was conducted from September 2014 to December 2015. Key assumptions for calculations in each category are presented below.

Medical spending

Studies of cancer clinical trial participation suggest that patients prefer maintaining continuity with their oncologist, receiving treatment close to home, and avoiding logistical challenges, such as driving long distances.13–15 On the basis of these preferences, we assumed that patients staying in-state for a clinical trial will also remain in-state for the rest of their cancer care. We calculated total medical spending for each patient as first-year treatment costs (only for newly diagnosed patients) plus continuing treatment costs for each year until death and the additional costs associated with a cancer-related death. We estimated medical costs separately for seven different cancer sites (breast, colorectal, leukemia, liver, lung and bronchus, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and prostate) as well as for an “other” category (for remaining cases). Of note, we assumed that in-state health outcomes are similar to those the patient would experience at an out-of-state facility. Implicit in this assumption is the idea that patients requiring specialized care (e.g., esophagectomy)6,8 are treated at the higher-volume KUCC and that outcomes at KUCC are similar to those at other regional care centers. There is evidence to suggest improved outcomes for trial participation among lung, colon, and breast cancer patients16 and differences in survival rates by hospital type,17 but it is unclear how much of the difference is attributable to treatment sites and how much is driven by patient and environmental characteristics. (Limitations of this assumption are addressed in the Discussion.)

Medical expenditures are likely to come from a variety of private sources (e.g., patients’ out-of-pocket costs, private insurers) and public sources (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare). To ensure that we were capturing new economic activity in Kansas, we restricted our impact analysis to patients who, prior to 2010, would have been expected to go out of state for clinical trial participation and cancer care on the basis of 2007–2008 outmigration patterns. Retaining these patients in-state for clinical trial participation and cancer care would result in new revenue even if the spending was funded by the state of Kansas.

The Kansas cancer patients included in our analysis came from two main groups: patients newly diagnosed in 2014 (n = 13,400) and patients living with cancer post diagnosis in 2014 (n = 119,171). The number of new cases was estimated using a 10-year (2003–2012) average of new diagnoses from the Kansas Cancer Registry.18 Existing cases (n = 119,171) were estimated by subtracting the number of new diagnoses (n = 13,400) from NCI estimates of the number of Kansans living with cancer in 2014 (n = 132,571).19 Costs for each of the seven cancer sites were taken from data provided by the NCI’s annualized mean net cost-of-care estimates.20,21

In equation form, we estimated:

|

Here, T is the number of years from diagnosis to death, i represents an individual patient, and j represents the cancer site. The number of years of continuing care is calculated by cancer site as the difference between the average age at death and average age at diagnosis.

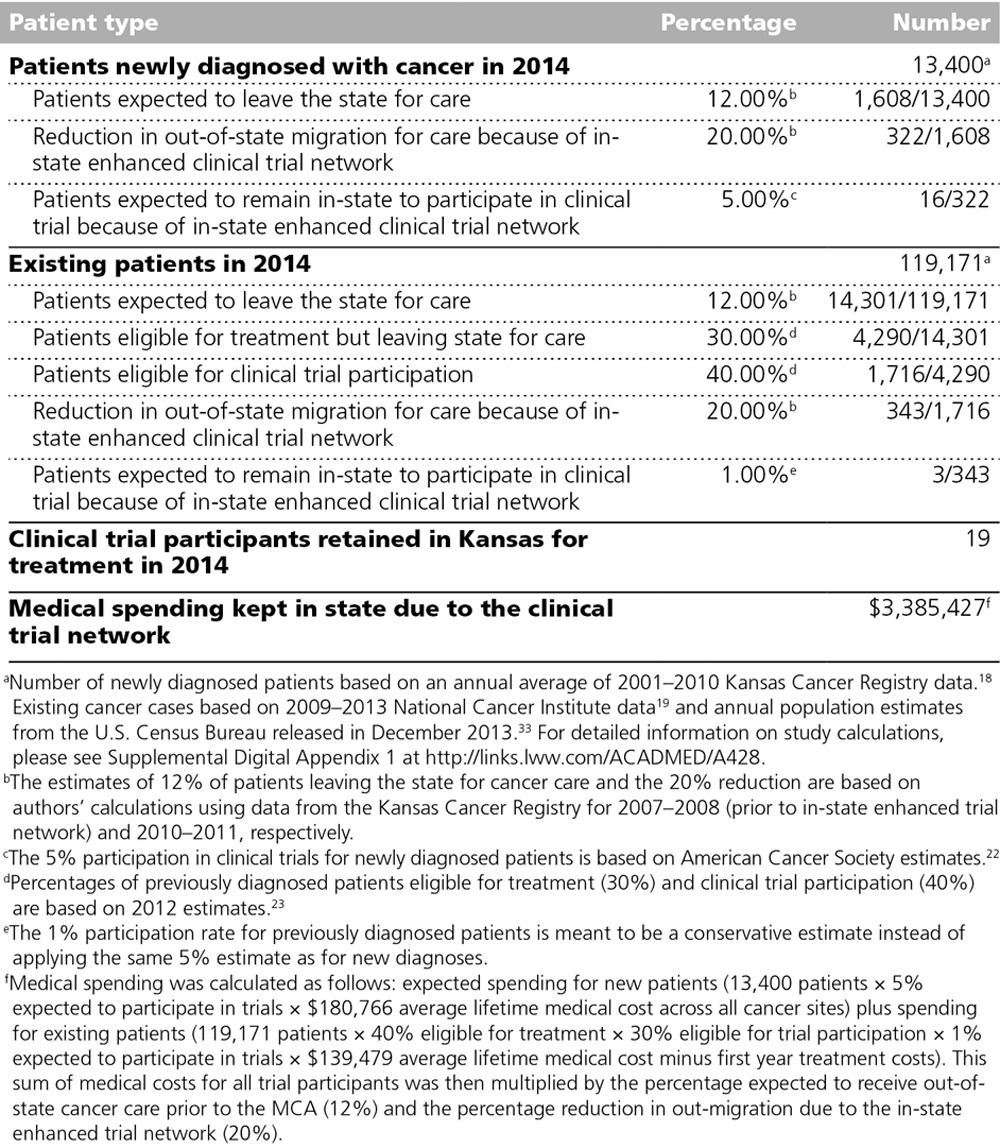

Key assumptions about Kansas cancer patients’ treatment locations and trial participation for our medical expenditure estimates are presented in Table 1. On the basis of data from the Kansas Cancer Registry, we calculated that 12% of Kansans with cancer were receiving some or all of their care in another state in 2007–2008. Following implementation of an enhanced local clinical trial network in 2010 in Kansas through the MCA, 10% of Kansans were going out of state for care, representing a nearly 20% reduction in outmigration. We assumed that 5% of newly diagnosed individuals with cancer participate in clinical trials on the basis of national estimates of trial participation.22 (A sensitivity analysis was conducted for higher and lower participation rates of 6% and 4%, respectively.) For existing cases, we took into account that only a portion will be eligible for any form of treatment (30%), and of these patients only a fraction will be eligible for a clinical trial (40%).23 Finally, only a certain percentage of those eligible for a trial will actually participate (1%).23

Table 1.

Key Assumptions About Kansas Cancer Patients in 2014 for Estimating Changes in Medical Spending Following the 2010 Expansion of the Cancer Clinical Trial Network in Kansas Through the Midwest Cancer Alliance (MCA)

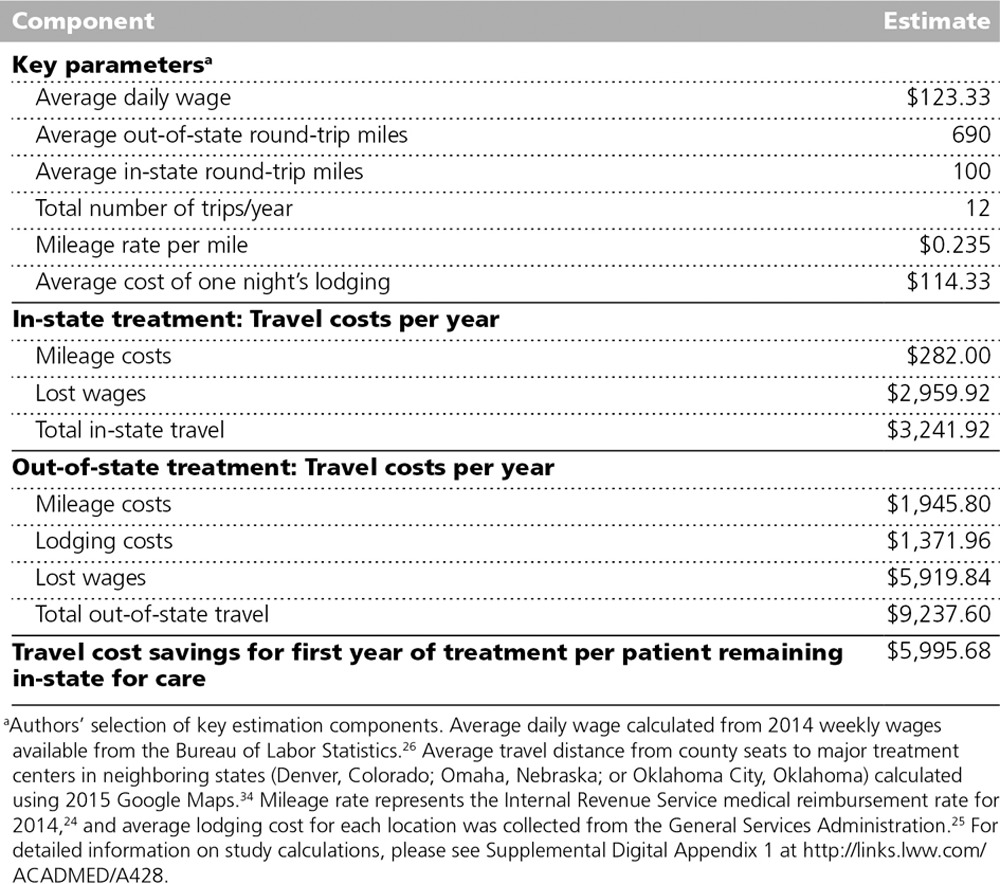

Travel cost savings

Receiving care closer to home means less travel-related expenses for households. Our key assumptions for travel expenses are presented in Table 2. Travel expenses were estimated only for newly diagnosed patients, whom we assumed would make one trip per month in the year following diagnosis. We calculated travel cost savings as the difference between expected in-state travel expenses and expected out-of-state travel expenses. The cost of in-state travel was based on an average 100-mile round-trip to the nearest treatment facility and one day of missed work for the patient and an accompanying working-age adult. The cost of out-of-state travel was based on average driving distance to major treatment facilities in neighboring states (Denver, Colorado; Omaha, Nebraska; or Oklahoma City, Oklahoma), one night of lodging, and two days of missed work for the patient and a companion.

Table 2.

Key Assumptions for Estimating Newly Diagnosed Patients’ Travel Expense Changes in 2014, Following the 2010 Expansion of the Cancer Clinical Trial Network in Kansas Through the Midwest Cancer Alliance

We determined the average round-trip distance for out-of-state treatment to be 690 miles. The cost of each trip was calculated as the round-trip mileage times the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) medical travel reimbursement rate ($0.235)24 plus one night of lodging at the General Services Administration reimbursement rate for the treatment location.25 The mean lodging rate was $114 across all out-of-state locations. The mean daily wage rate for all Kansas counties ($123) was used to calculate foregone wage costs.26

Grant revenue

Grant revenue was included for trial participants in the MCA trial network. During the first five years of operation (2010–2014), MCA trials generated an average of $56,000 in grant revenue per year through direct payment for clinical trial participation. This amount does not include other grant revenue that accrued because of enhanced clinical trial opportunities.

Indirect and induced economic effects

Indirect and induced economic effects were estimated using the Kansas IMPLAN27 (Impact Analysis for Planning) model. IMPLAN is a widely used input–output model that allows researchers to estimate how increases (or decreases) in inputs in one or more industry (e.g., health care) affect outputs in that industry and all other industries. IMPLAN uses national-, state-, and county-level data to calculate economic impacts.28 Indirect and induced effects, which are often called multipliers, account for secondary economic impacts related to the enhanced trial network. Indirect effects represent changes in nonwage inputs within the same industry, such as additional purchases from local medical suppliers who in turn rent more business space and purchase more office supplies and equipment. Induced effects represent the economic impact of changes in household income. That is, as more patients are treated in-state, more is paid in wages to local workers who then spend this income on goods (e.g., groceries) and services (e.g., daycare). IMPLAN allows dollars to be entered into the model in different sectors. We included medical spending and grant income in the medical sector and travel cost savings as additional funds available to households for consumption.

Results

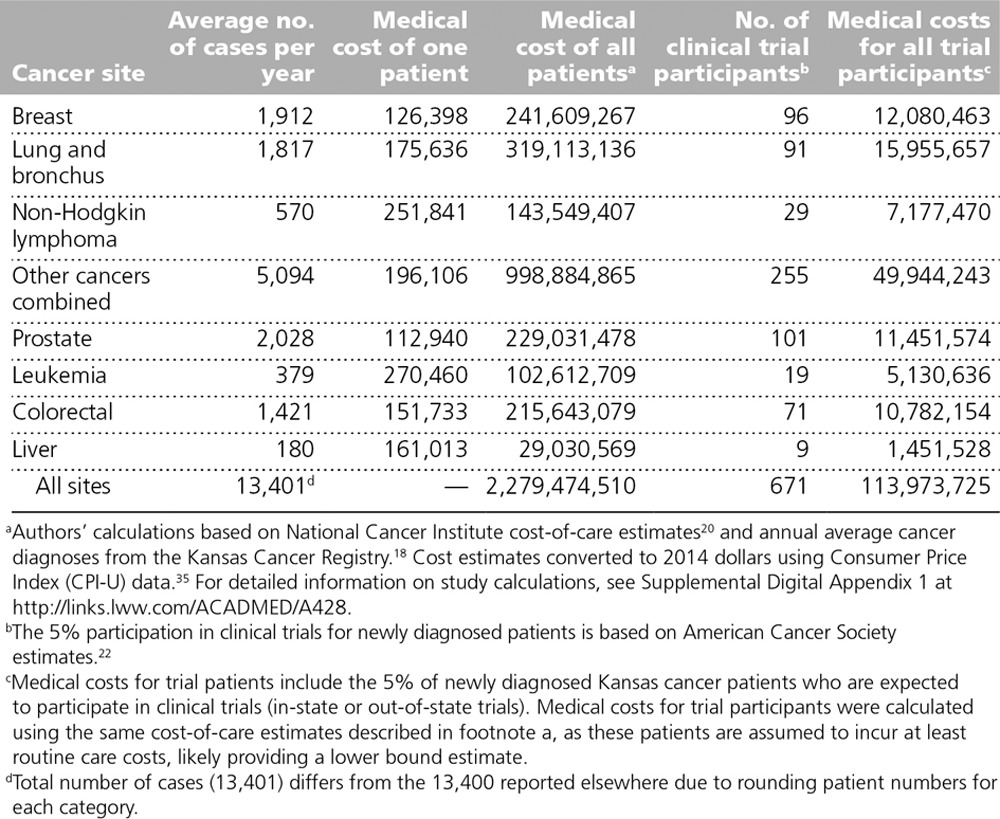

We estimated the total lifetime cost of cancer care for all Kansas patients newly diagnosed in 2014 (n = 13,400) to be $2.3 billion (Table 3). Only a small portion of these patients (n = 671) received treatment through a cancer clinical trial, representing about $114 million in lifetime medical spending. Per patient estimates of average lifetime cancer-related medical expenditures (in 2014 dollars) ranged from $112,940 for prostate cancer to $270,460 for leukemia. We multiplied the average cost of care for each cancer site by the number of newly diagnosed cases to get a total cost of medical care in each category. These ranged from about $29 million for liver cancer to almost $1 billion for “other” cancers.

Table 3.

Estimated Lifetime Cost of Medical Care, in 2014 U.S. Dollars, for Kansas Cancer Patients Newly Diagnosed in 2014

We estimate that $3.4 million in medical spending was generated in 2014 by the enhanced local clinical trial network, which retained an estimated 19 patients (16 newly diagnosed and 3 previously diagnosed) in-state for trials and care in 2014 (Table 1). Of note, the enhanced local clinical trial network might have also induced individuals to participate in trials who would have not participated if faced with traveling to another state. We did not include these individuals in our economic impact numbers because it is unlikely that they would have left the state for treatment in the absence of the MCA. On the basis of pre-MCA expectations, we estimated that about 300 additional newly diagnosed Kansas cancer patients remained in-state for cancer care in 2014. Some of these patients might have remained in-state because of the MCA and the increased perceptions of high-quality in-state treatment options. We would expect this reputational effect to grow over time, but we included only the 19 expected trial participants in our present estimates.

Travel cost savings for cancer clinical trial participants remaining in-state averaged about $6,000 per patient for the 16 newly diagnosed patients retained in-state for trial participation in 2014 (Table 2), for a total of about $100,000. In terms of economic activity, these travel savings represent only 3% of the medical spending estimates. However, for individual households, $6,000 likely represents a significant financial gain.

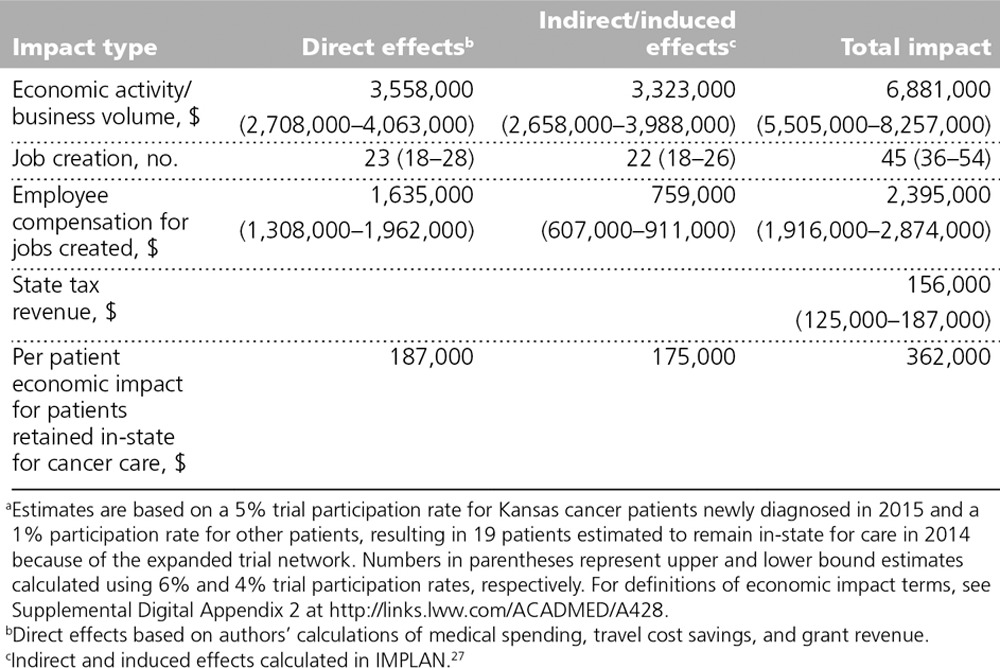

Estimates of direct, indirect/induced, and total economic impacts of medical spending, travel cost savings, and grant revenue are presented in Table 4. (Estimated ranges based on higher and lower trial participation rates of 4% and 6%, respectively, are included in the table in parentheses). We estimated that the enhanced cancer clinical trial network in Kansas resulted in a total of about $6.9 million in 2014 that would not have otherwise occurred in the state. This estimate includes about $3.6 million in direct spending and about $3.3 million in indirect/induced effects. The indirect/induced effects represent a multiplier effect of 0.92 (i.e., a 1-dollar increase in economic activity from enhanced local trials leads to an additional 92 cents of economic activity). The enhanced clinical trial network generated an estimated 23 jobs from increased direct medical spending for cancer care, with an average wage of $70,000, and an additional 22 jobs through indirect/induced effects, with an average annual wage of $35,000. Economic activity associated with the enhanced trial network generated an additional $156,000 in state tax revenue for 2014 (local tax revenues were not estimated).

Table 4.

Estimated 2014 Economic Impacts of the 2010 Expansion of the Kansas Cancer Clinical Trial Network, in 2014 U.S. Dollarsa

Per patient economic impact estimates are included in the last row of Table 4. We estimated that each patient retained in-state resulted in $362,000 in additional economic activity in 2014: $187,000 in direct medical spending, travel cost savings, and grant revenue plus $175,000 in indirect/induced effects. Because our estimates were based on national medical spending estimates and trial participation rates, our per patient estimates for Kansas can serve as a rough estimate for patients retained for cancer care in other states, although indirect and induced effects estimates will differ to some degree on the basis of local economic conditions.

Discussion

Our estimates suggest that retaining a modest number of patients in-state for care can substantially benefit state and local economies. In the case of Kansas, the enhanced cancer clinical trial opportunities created through the MCA’s partnerships with providers across the state coupled with the presence of an emerging regional care center at KU Medical Center resulted in $6.9 million in 2014 economic activity that would have otherwise occurred in other states. These results are consistent with previous research suggesting high costs of cancer care and substantial economic impacts from retaining more patients in-state for care.29,30

This approach of expanding both local treatment options and specialized in-state regional care led to increased economic activity without sacrificing better survival rates for specialized care that patients might have experienced at high-volume care centers in other states. The net effect of in-state care on patient well-being and the state economy would be less clear if high-volume specialized care were only available out of state. In that case, local care might increase quality of life during treatment but reduce well-being and wages earned in the longer run because of lower survival rates.5–8

Enhanced clinical trials in an AMC context

The enhanced clinical trial network addresses several key elements in the KU Medical Center mission. The network expands research potential and patient care. Partnerships in the MCA and continued use of telemedicine better serve patients in isolated rural areas, and enhanced capacity for specialized cancer care on the AMC’s urban campus provides an in-state option for high-volume specialized care. Additionally, the clinical trial network addresses the AMC’s commitment to economic development within the state.

Enhanced clinical trials in a policy context

Policy provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) might increase interest in cancer clinical trial participation over time. The ACA requires coverage for routine care costs for patients enrolled in clinical trials.31 Plans in effect prior to the enactment of the ACA are exempted from this provision through a grandfather clause, but fewer plans will meet this criterion over time, leading to expanded clinical trial coverage. Of note, Medicaid programs are not subject to ACA coverage provisions, which limits the potential effects of expansion of trial participation in states, like Kansas, where routine care coverage is not mandated for trial participants.32

Limitations

We note several limitations to our economic impact analysis. First, there are a number of factors that do not lend themselves to quantification, including the psychological and quality-of-life effects of trial participation for individuals with cancer and their families. Some of these factors might have economic consequences (e.g., stress effects on work attendance and performance), and others might predominantly affect quality of life. To the extent that patients prefer care closer to home and there are no significant differences in health outcomes across treatment sites, these unquantified effects likely mean our economic effects are underestimated. Additionally, we captured only short-term effects of the enhanced clinical trial network. Data are not readily available for longer-term effects, which might include more expertise and collaboration in cancer treatment, more capacity for cancer prevention and early detection, and higher cancer survival rates. Finally, the enhanced clinical trial network might induce residents of other states to travel to Kansas for cancer care, increasing medical and travel-related spending in the state. All of these factors could lead to an actual economic impact that is larger than the estimates presented.

Conclusions

Local cancer clinical trial options allow patients to remain closer to home and enhance the state economy. Our estimates indicate that the 2010 expansion of local trial options in Kansas through the MCA resulted in an additional $6.9 million in economic activity in 2014 that would have otherwise occurred in other states. The majority of this economic activity can be attributed to medical spending for cancer care generated by retaining about 19 patients in-state—just a small portion of the approximately 1,600 newly diagnosed individuals and 14,000 existing patients receiving cancer care outside the state each year.

Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful for data, administrative details, and useful comments from staff and faculty at the Midwest Cancer Alliance and the University of Kansas Cancer Center as well as the Mary Babb Randolph Cancer Center and Center for Business and Economic Research at West Virginia University.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A428.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the Midwest Cancer Alliance.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable (not human subjects research).

References

- 1.Butow PN, Phillips F, Schweder J, White K, Underhill C, Goldstein D; Clinical Oncological Society of Australia. Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients living in urban and rural/regional areas: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1–22.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones AP, Haynes R, Sauerzapf V, Crawford SM, Zhao H, Forman D. Travel time to hospital and treatment for breast, colon, rectum, lung, ovary and prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:992–999.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambroggi M, Biasini C, Del Giovane C, Fornari F, Cavanna L. Distance as a barrier to cancer diagnosis and treatment: Review of the literature. Oncologist. 2015;20:1378–1385.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lüchtenborg M, Riaz SP, Coupland VH, et al. High procedure volume is strongly associated with improved survival after lung cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3141–3146.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:511–520.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reames BN, Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg. 2014;260:244–251.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mesman R, Westert GP, Berden BJ, Faber MJ. Why do high-volume hospitals achieve better outcomes? A systematic review about intermediate factors in volume–outcome relationships. Health Policy. 2015;119:1055–1067.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2128–2137.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Success of clinical trial participation depends on appropriate funding. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3(1):30–31.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards RL, Lofgren RP, Birdwhistell MD, Zembrodt JW, Karpf M. Challenges of becoming a regional referral system: The University of Kentucky as a case study. Acad Med. 2014;89:224–229.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cancer Institute. Comparison of Cooperative Group Program funding and NCTN Program funding. http://www.cancer.gov/research/areas/clinical-trials/nctn/funding-nctn-program-funding. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 12.McCaskill-Stevens W, Clauser S. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (2012). Presentation to the National Cancer Advisory Board, November 29, 2012. http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/ctac/archive/1112/Stevens.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horn L, Keedy VL, Campbell N, et al. Identifying barriers associated with enrollment of patients with lung cancer into clinical trials. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14:14–18.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baggstrom MQ, Waqar SN, Sezhiyan AK, et al. Barriers to enrollment in non-small cell lung cancer therapeutic clinical trials. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:98–102.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basche M, Barón AE, Eckhardt SG, et al. Barriers to enrollment of elderly adults in early-phase cancer clinical trials. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:162–168.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow CJ, Habermann EB, Abraham A, et al. Does enrollment in cancer trials improve survival? J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:774–780.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfister DG, Rubin DM, Elkin EB, et al. Risk adjusting survival outcomes in hospitals that treat patients with cancer without information on cancer stage. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1303–1310.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kansas Cancer Registry. Kansas Cancer Registry multiple year report: Cancer incidence in Kansas 2003–2012. http://www.kumc.edu/kcr/CancerStats/01_KCR_MYR_2003-2012_Intro.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute. State cancer profiles, quick profiles: Kansas, prevalence table 2014. http://www.statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/index.html. Accessed December 12, 2014. [No longer available.]

- 20.National Cancer Institute. Annualized mean net costs of care. 2011. https://costprojections.cancer.gov/annual.costs.html. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- 21.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Cancer Society. Clinical trials: What you need to know. 2016. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003006-pdf.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 23.Oncology Solutions. Statewide Cancer Clinical Trial Network. April 2012; Morgantown, WV: Presentation to the West Virginia Oncology Society. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Internal Revenue Service. 2014 standard mileage rates. 2013. https://www.irs.gov/2014-standard-mileage-rates-for-business-medical-and-moving-announced. Accessed September 9, 2015.

- 25.General Services Administration. Per diem rates. http://www.gsa.gov/portal/content/104877. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 26.Bureau of Labor Statistics. County Employment and Wages in Kansas Second Quarter 2014. 2014Kansas City, MO: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Mountain Plains Information Office. [Google Scholar]

- 27.IMPLAN Web site. http://www.implan.com/. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 28.Mulligan G, Jackson R, Krugh A. Economic base multipliers: A comparison of ACDS and IMPLAN. Reg Sci Policy Pract. 2013;5(3):289–303.. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurley-Calvez T, Bose S. The Economic Impact of Cancer in West Virginia. 2013. Morgantown, WV: University of West Virginia; http://www.be.wvu.edu/bber/pdfs/BBER-2013-02.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown ML, Yabroff KR. Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni J. Economic impact of cancer in the United States. In: Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 2006:Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 202–214.. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Cancer Institute. Insurance coverage and clinical trials. 2016. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/paying/insurance. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 32.Mackay CB, Gurley-Calvez T, Erickson KD, Jensen RA. Clinical trial insurance coverage for cancer patients under the Affordable Care Act. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2016;2:69–74.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References cited in tables only

- 33.U.S. Census Bureau. Table 1. Annual estimates of the population for the United States, regions, states, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/state/totals/2013/tables/NST-EST2013-01.xls. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 34.Google Maps. https://www.google.com/maps/. Accessed September 2015.

- 35.InflationData.com. Historical consumer price index (CPI-U) data. http://inflationdata.com/inflation/consumer_price_index/historicalcpi.aspx?reloaded=true. Accessed December 14, 2016.