Abstract

Objective

To compare clinical and ultrasonographic (US) evaluation of Achilles enthesitis in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Methods

The Achilles insertion of outpatients with PsA was examined by clinical assessment of tenderness and US evaluation of (1) inflammatory activity (defined as the presence of power Doppler signal, tendon thickening and/or hypoechogenicity) and (2) structural damage (defined as the presence of erosions, calcifications and/or enthesophytes). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed0.4 to explore the associations between clinical characteristics and US scores.

Results

282 Achilles tendons in 141 patients with PsA were assessed. Mean (SD) age was 52.4 (10.2) years, disease duration 9.5 (6.6) years and 50.4% were females. Palpatory tenderness was found in 88 (31.2%), US-verified inflammatory activity in 46 (16.3%) and structural damage in 148 (52.5%) of the Achilles. Total US scores, as well as their components, were similar for patients with and without palpatory tenderness. None of the clinical characteristics were associated with inflammatory activity. Age, body mass index (BMI), regular physical exercise and current use of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) were associated with structural damage.

Conclusion

There appears to be a lack of association between clinical and US signs of Achilles enthesitis in PsA. Age, BMI, regular physical exercise and current use of bDMARDs were associated with structural damage on US.

Keywords: Psoriatic Arthritis, Ultrasonography, Disease Activity

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Recent studies have indicated the benefit of ultrasonography (US) evaluation in addition to clinical evaluation in psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

What does this study add?

Our findings underline the discordance between clinical and US evaluation of Achilles enthesitis in PsA. None of the clinical characteristics were associated with inflammatory activity at the Achilles, whereas structural damage was associated with age, body mass index, regular physical exercise and current use of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

How might this impavious studies,ct on clinical practice?

Our study underlines the importance of US evaluation in addition to clinical evaluation of Achilles enthesitis in PsA. The data from our study, along with that from previous studies, lead to the question if inflammatory findings ought to be more weighted than structural damage in the further development of US enthesitis scores, which currently include both inflammatory signs and structural damage.

Introduction

Evaluation of inflammation and structural integrity of periarticular structures such as entheses can be challenging. This is even the case for large, accessible entheses such as the Achilles tendon insertions. It has been suggested that enthesitis may be both overestimated and underestimated by clinical examination in psoriatic arthritis (PsA).1–4 Ultrasonography (US) is a sensitive tool for the assessment of musculoskeletal inflammation, including enthesitis, and is increasingly used in clinical practice, where it may be considered as an extension of the clinical examination.5 We have previously reported significant discrepancies between US and clinical findings in PsA.6

In the present study, we aimed to compare the clinical and US evaluation of Achilles enthesitis, an enthesitis site frequently affected in patients with PsA. Further, we aimed to explore the associations between US-verified Achilles enthesitis and clinical characteristics.

Methods

Patients

In total, there were 581 patients with PsA registered in the outpatient clinic of the Hospital of Southern Norway Trust, Norway, during the study period from January 2013 to May 2014, of whom 471 fulfilled the ClASsification for Psoriatic ARthritis criteria.7 Of these 471 patients, 141 were included in the study in a random manner by the study nurses at consecutive clinic visits.6 All the included patients had peripheral inflammatory involvement clinically.7 A comparison of the study participants and non-participants is previously reported (online supplementary table 1).6 Clinical examination of the Achilles tendons was performed by two specially trained nurses, unaware of the US findings. The presence of clinical enthesitis was defined as tenderness on firm palpation at the insertion of the Achilles tendon. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), medication, smoking status, regular physical exercise (cannot exercise due to disability or handicap/do not exercise regularly/exercise one to two times per month/one to two times per week/three or more times per week), C reactive protein (CRP, mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, mm/h) were assessed.

rmdopen-2017-000486supp001.docx (16.3KB, docx)

US protocol

US evaluation of the Achilles entheses was performed by a rheumatologist experienced in US (APD) on the day of clinical examination. The patients were prone positioned with ankles in passive plantar flexion. The US studies were performed using two US devices (Siemens Acuson S2000 or GE logic E) both with a multifrequency linear transducer (6–18 MHz). The complete US protocol is previously described, including a head-to-head comparison of the two US devices showing very good agreement of kappa with linear weighting for grey scale (0.88, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.0) and power Doppler (PD: 1.00, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.0) enthesitis.6 Resolution of the images was improved by using the highest B-mode frequency of the probe still permitting favourable resolution in the depth. Imaging parameters were adjusted to optimise the contrast between examined structures. PD frequency of 9 (10) MHz was used with a pulse repetition frequency of 391 (400) Hz. PD gain was optimised by increasing gain until artefacts appeared, then by reducing gain until artefacts disappeared. The following assessments were made both longitudinally and transversely on the Achilles entheses: (1) inflammatory activity defined as the presence of hypoechogenicity, tendon thickening and/or PD signal (approximately <2 mm from the bony cortex) and (2) structural damage defined as the presence of calcifications, enthesophytes and/or erosions at tendon insertion (cortical breakage with a step down contour defect seen in two perpendicular planes at the insertion of the entheses to the bone) in accordance with current guidelines.8 9 US sum scores of inflammatory activity (0–3) and structural damage (0–3) of the Achilles were assessed.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (V.21.0.0.2). Demographic variables and US scores were assessed by descriptive statistics. Proportions were analysed by X2 test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Correlations were assessed by Spearman's rank correlation test (non-normal distribution of data). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to explore the associations between clinical characteristics (age, sex, disease duration, BMI, smoking, current use of steroids and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), CRP, ESR, regular physical exercise (one to two times per month or more; yes/no) and the presence of inflammatory or structural damage on US. A univariate p-value of 0.25 was used for variable selection and a p-value of 0.05 to keep the variable in the model. Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics was performed for testing of goodness of fit.

Results

Patients’ demographic characteristics and medications are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and medications

| Age, years* | 52.4 (10.2) |

| Disease duration, years* | 9.5 (6.6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2* | 28.3 (4.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 71 (50.4) |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 24 (17) |

| Not performing physical exercise, n (%) | 63 (44.7) |

| Erosive disease on X-ray of hands and feet, n (%) | 38 (26.6) |

| C reactive protein, mg/L† | 2 (0–63) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm† | 13 (2–64) |

| DAS28ESR† | 3.2 (0.6–6.4) |

| SDAI† | 8.6 (0.1–39.5) |

| Current use of NSAIDs, n/total (%) | 45/139 (32.4) |

| Current use of steroids, n (%) | 15 (10.6) |

| Mean (SD), mg daily dose among users | 4.4 (1.2) |

| Current use of csDMARDs, n (%) | 81 (57.4) |

| Methotrexate, n (%) | 50 (35.5) |

| Leflunomide, n (%) | 29 (20.6) |

| Sulfasalazine, n (%) | 2 (1.4) |

| Current use of bDMARDs, n (%) | 46 (32.6) |

| Adalimumab, n (%) | 19 (13.5) |

| Etanercept, n (%) | 13 (9.2) |

| Golimumab, n (%) | 8 (5.7) |

| Infliximab, n (%) | 5 (3.5) |

| Certolizumab, n (%) | 1 (0.7) |

*Mean (SD).

†Median (range).

bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DAS28ESR, 28-joint Disease Activity Score with erythrocyte sedimentation rate; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

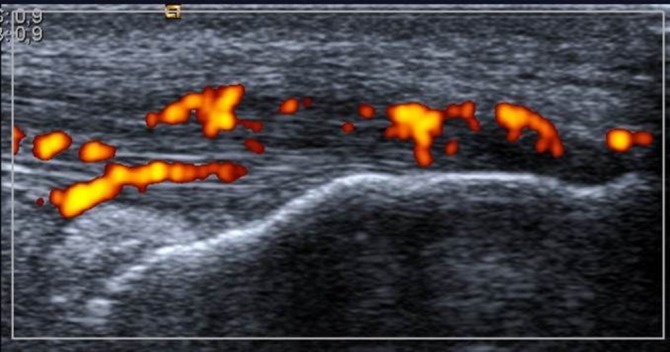

Examples of inflammatory and structural findings of Achilles enthesitis are displayed in figure 1. US findings of inflammatory activity and structural damage of the Achilles are summarised in table 2.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal scan of the Achilles tendon insertion. Grey scale structural pathology present: hypoechogenicity, increased thickness on the bony insertion. Power Doppler present.

Table 2.

Ultrasonography findings of 282 Achilles tendons

| No clinical Achilles enthesitis (n=194) |

Clinical Achilles enthesitis (n=88) |

p Value | |

| Inflammatory activity | 31 (16.0) | 15 (17.0) | 0.82 |

| Hypoechogenicity | 10 (5.2) | 7 (8.0) | 0.36 |

| Tendon thickening | 27 (13.9) | 10 (11.4) | 0.56 |

| Power Doppler activity | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1.00 |

| Structural damage | 100 (51.5) | 48 (54.5) | 0.64 |

| Calcifications | 77 (39.7) | 35 (39.8) | 0.99 |

| Enthesophytes | 51 (26.3) | 26 (29.5) | 0.57 |

| Erosions at tendon insertion | 4 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0.31 |

| Inflammatory activity and/or structural damage | 112 (57.7) | 56 (63.6) | 0.35 |

According to X2 test or Fischer's exact test as appropriate. Data are displayed as n (%).

The US results were similar for patients with and without palpatory tenderness of the Achilles. A weak correlation was found between inflammatory activity on US and CRP (r=0.13, p=0.03) but not ESR (r=0.002, p=0.98). Subclinical inflammation was found in 31 (11%) of the Achilles insertions. Structural damage was found in 48 (54.5%) of the tender Achilles. No significant difference in percentages of patients with Achilles inflammatory activity or structural damage was found when comparing patients with DAS28ESR <2.6 and ≥2.6 or patients currently treated or not with bDMARDs, conventional synthetic DMARDs and steroids, except for a higher percentage of patients with structural damage among the bDMARD treated patients (62.6% vs 47.6%, p=0.02). Mean (SD) BMI was similar between patients with versus without US inflammatory activity (p=0.64) but significantly higher in patients with versus without US structural damage (28.9 kg/m2 (4.4) vs 27.7 kg/m2 (4.2), p=0.02). As secondary analyses, we explored the clinically positive but US negative Achilles (n=33), with findings of one patient each with subtalar arthritis, talocrural arthritis, talonavicular arthritis and medial tenosynovitis of the ankle as well as two patients with flexor hallucis tenosynovitis. Corresponding pathologies were similar for patients without palpatory tenderness at the Achilles.

Logistic regression

By means of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, age, regular physical exercise, BMI and current use of bDMARDs were associated with structural damage on US (table 3). The findings were valid also when adjusted for gender and disease duration. Disease duration (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.00, p=0.05) was the only variable associated with inflammatory activity on US in univariate analyses but was no longer significant when adjusted for age and gender.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of ultrasonographic-verified structural damage of the Achilles

| Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 1.04 | 1.02 to 1.07 | 0.001 | 1.04 | 1.02 to 1.07 | 0.001 |

| Female gender | 1.09 | 0.68 to 1.74 | 0.73 | – | – | – |

| Disease duration, years | 1.05 | 1.01 to 1.09 | 0.009 | – | – | – |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 1.07 | 1.01 to 1.13 | 0.02 | 1.07 | 1.01 to 1.14 | 0.02 |

| Currently smoking | 1.09 | 0.58 to 2.02 | 0.80 | – | – | – |

| Current use of steroids | 1.21 | 0.56 to 2.59 | 0.63 | – | – | – |

| Current use of bDMARDs | 1.84 | 1.11 to 3.07 | 0.02 | 1.83 | 1.08 to 3.12 | 0.03 |

| CRP, mg/L | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.05 | 0.31 | – | – | – |

| ESR, mm/h | 1.01 | 0.99 to 1.03 | 0.29 | – | – | – |

| Regular physical exercise | 1.70 | 1.06 to 2.72 | 0.03 | 1.92 | 1.16 to 3.17 | 0.01 |

bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; CRP, C reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Discussion

Achilles enthesitis defined by US was not significantly associated with clinical enthesitis in this population of patients with PsA. Our findings underline the value of US evaluation in addition to clinical evaluation of entheses in PsA. US may give detailed information of both inflammatory and structural damage of entheses and thus could facilitate optimal treatment monitoring.2 5 Interestingly, the percentage of patients with acute inflammation and/or structural damage was similar for the groups with and without palpatory tenderness. This suggests that there may be limited value of clinical examination compared with US evaluation. In fact, US of the Achilles has previously been proposed in the diagnosis of early psoriatic arthropathy, as a sensitive method for early diagnosis.10

The optimal definition of US enthesitis has been debated, leading to the recent publication endorsed by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology attempted to define what constitutes normal entheses as well as elementary lesions consistent with enthesitis.9

For most US findings indicative of Achilles enthesopathy, the interobserver and intraobserver reliability has been reported to be moderate to excellent.11 Standardisation of US evaluation may improve inter-rater reliability.12

Structural damage of the Achilles may be related not only to previous inflammation, but also to factors such as traumatic injuries, degeneration and even metabolic disorders.2 We found structural damage of the Achilles associated with age and BMI, in accordance with previous observations.13 14 More interestingly, we also found structural damage associated with current use of bDMARDs—which may be related to a history of higher disease activity in these patients—as well as with regular physical exercise. The association between structural damage and age, BMI and regular physical activity may relate to increased mechanical stress over time. This leads to the question as to what extent structural damage of the Achilles may be seen in healthy subjects. In patients with psoriasis, subclinical enthesitis has been reported to be a frequent finding.14–16 Enthesophytes of the Achilles were, in a previous study, found in a third of healthy controls compared with 90% of patients with psoriasis.14 In the same study, Achilles tendon thickening was reported in only 1 of 30 healthy controls. Importantly, structural changes of the Achilles are also known to be a rather frequent finding in athletes and after entheses overuse.17 18

The data from our study, along with that from previous studies, lead to the question if inflammatory findings ought to be more weighted than structural damage in the further development of US enthesitis scores, which currently include both inflammatory signs and structural damage.4 5 19–21

Limitations of the study include the cross-sectional, single-blinded design. For future studies, a longitudinal double-blinded design would allow the assessment of predictors of Achilles enthesitis and further evaluation of the long-term outcome of acute inflammation as regards structural damage. Furthermore, eventual walking before the US assessment—which is shown to increase US enthesitis scores—was not recorded.22 A further limitation is the rather rare finding of inflammatory activity, particularly PD signals. In rheumatoid arthritis, the correlation between clinical and US findings of arthritis is found to be stronger in cohorts with high compared with low disease activity.23 However, with wider therapeutic options and a great focus on treating to target, many patients do achieve low disease activity. Indeed, a strength of the study is the evaluation of a large group of outpatients with PsA in a real-life setting, providing validity to the results. Further, this is the first study to explore the association between structural findings at the Achilles and physical exercise in PsA.

In conclusion, we report the lack of association between clinical and US signs of Achilles enthesitis in PsA. Age, BMI, regular physical exercise and current use of bDMARDs were associated with structural damage on US.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for participating in this study and the local rheumatology staff for data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: BM, APD, DMS, HBH, AK and GH were responsible for the study design. BM, APD, DMS and GH were responsible for the data acquisition. BM analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer (grant number WS1948310) (GH) and with a clinical research fellowship from the Hospital of Southern Norway Trust (BM).

Competing interests: GH has received an unrestricted grant from Pfizer for this research project on psoriatic arthritis. GH is the founder of the GoTreatIt Rheuma computer software and a shareholder in DiaGraphIt manufacturing system. All other authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (Regional komité for Medisinsk og helsefaglig forskningsetikk Midt-Norge 2012/101) and appropriate Institutional Review Boards.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant data are within the text.

References

- 1.Freeston JE, Coates LC, Helliwell PS, et al. Is there subclinical enthesitis in early psoriatic arthritis? A clinical comparison with power doppler ultrasound. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1617–21. 10.1002/acr.21733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riente L, Carli L, Delle Sedie A. Ultrasound imaging in psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32:S26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandinelli F, Prignano F, Bonciani D, et al. Ultrasound detects occult entheseal involvement in early psoriatic arthritis independently of clinical features and psoriasis severity. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013;31:219–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Agostino MA, Said-Nahal R, Hacquard-Bouder C, et al. Assessment of peripheral enthesitis in the spondylarthropathies by ultrasonography combined with power Doppler: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:523–33. 10.1002/art.10812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delle Sedie A, Riente L. Psoriatic arthritis: what ultrasound can provide us. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33:S60–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michelsen B, Diamantopoulos AP, Hammer HB, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation in psoriatic arthritis is of major importance in evaluating disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:2108–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. 10.1002/art.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakefield RJ, Balint PV, Szkudlarek M, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound including definitions for ultrasonographic pathology. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2485–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terslev L, Naredo E, Iagnocco A, et al. Defining enthesitis in spondyloarthritis by ultrasound: results of a Delphi process and of a reliability reading exercise. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:741–8. 10.1002/acr.22191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pistone G, La Vecchia M, Pistone A, et al. Achilles tendon ultrasonography may detect early features of psoriatic arthropathy in patients with cutaneous psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:1220–2. 10.1111/bjd.13135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filippucci E, Aydin SZ, Karadag O, et al. Reliability of high-resolution ultrasonography in the assessment of Achilles tendon enthesopathy in seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1850–5. 10.1136/ard.2008.096511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'agostino MA, Aegerter P, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. How to evaluate and improve the reliability of power Doppler ultrasonography for assessing enthesitis in spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:61–9. 10.1002/art.24369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eder L, Jayakar J, Thavaneswaran A, et al. Is the MAdrid Sonographic Enthesitis Index useful for differentiating psoriatic arthritis from psoriasis alone and healthy controls? J Rheumatol 2014;41:466–72. 10.3899/jrheum.130949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gisondi P, Tinazzi I, El-Dalati G, et al. Lower limb enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis without clinical signs of arthropathy: a hospital-based case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:26–30. 10.1136/ard.2007.075101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naredo E, Möller I, de Miguel E, et al. Ultrasound School of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology and Spanish ECO-APs Group. High prevalence of ultrasonographic synovitis and enthesopathy in patients with psoriasis without psoriatic arthritis: a prospective case-control study. Rheumatology 2011;50:1838–48. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez M, Filippucci E, De Angelis R, et al. Subclinical entheseal involvement in patients with psoriasis: an ultrasound study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011;40:407–12. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emerson C, Morrissey D, Perry M, et al. Ultrasonographically detected changes in Achilles tendons and self reported symptoms in elite gymnasts compared with controls -an observational study. Man Ther 2010;15:37–42. 10.1016/j.math.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boesen AP, Boesen MI, Koenig MJ, et al. Evidence of accumulated stress in Achilles and anterior knee tendons in elite badminton players. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:30–7. 10.1007/s00167-010-1208-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balint PV, Kane D, Wilson H, et al. Ultrasonography of entheseal insertions in the lower limb in spondyloarthropathy. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:905–10. 10.1136/ard.61.10.905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alcalde M, Acebes JC, Cruz M, et al. A sonographic enthesitic index of lower limbs is a valuable tool in the assessment of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1015–9. 10.1136/ard.2006.062174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Miguel E, Cobo T, Muñoz-Fernández S, et al. Validity of enthesis ultrasound assessment in spondyloarthropathy. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:169–74. 10.1136/ard.2007.084251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Méric JC, Grandgeorge Y, Lotito G, et al. Walking before an ultrasound assessment increases the enthesis score significantly. J Rheumatol 2011;38:961. 10.3899/jrheum.101059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dejaco C, Duftner C, Wipfler-Freissmuth E, et al. Ultrasound-defined remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: association with clinical and serologic parameters. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012;41:761–7. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2017-000486supp001.docx (16.3KB, docx)