Abstract

Objective:

To determine to what degree stroke mimics skew clinical outcomes and the potential effects of incorrect stroke diagnosis.

Methods:

This retrospective analysis of data from 2005 to 2014 included IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)–treated adults with clinical suspicion for acute ischemic stroke who were transferred or admitted directly to our 2 hub hospitals. Primary outcome measures compared CT-based spoke hospitals' and MRI-based hub hospitals' mimic rates, hemorrhagic transformation, follow-up modified Rankin Scale (mRS), and discharge disposition. Secondary outcomes were compared over time.

Results:

Of the 725 thrombolysis-treated patients, 29% were at spoke hospitals and 71% at hubs. Spoke hospital patients differed from hubs by age (mean 62 ± 15 vs 72 ± 15 years, p < 0.0001), risk factors (atrial fibrillation, 17% vs 32%, p < 0.0001; alcohol consumption, 9% vs 4%, p = 0.007; smoking, 23% vs 13%, p = 0.001), and mimics (16% vs 0.6%, p < 0.0001). Inclusion of mimics resulted in better outcomes for spokes vs hubs by mRS ≤1 (40% vs 27%, p = 0.002), parenchymal hematoma type 2 (3% vs 7%, p = 0.037), and discharge home (47% vs 37%, p = 0.01). Excluding mimics, there were no significant differences. Comparing epochs, spoke stroke mimic rate doubled (9%–20%, p = 0.03); hub rate was unchanged (0%–1%, p = 0.175).

Conclusions:

Thrombolysis of stroke mimics is increasing at our CT-based spoke hospitals and not at our MRI-based hub hospitals. Caution should be used in interpreting clinical outcomes based on large stroke databases when stroke diagnosis at discharge is unclear. Inadvertent reporting of treated stroke mimics as strokes will artificially elevate overall favorable clinical outcomes with additional downstream costs to patients and the health care system.

Thrombolytic-eligible stroke patient numbers have increased with expansion of onset-to-treatment (OTT) time from 3 hours to 4.5 hours.1,2 With quality improvement initiatives, such as Target: Stroke, reporting improved clinical outcomes with faster door-to-needle (DTN) times, stroke treatment continues to be optimized in hopes of improving functional outcomes. A correlation between decreasing DTN times and increasing rates of stroke mimic treatment with initial diagnosis based on clinical presentation and noncontrast head CT has been reported.3 Multiple studies of IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment of mimics demonstrate low hemorrhage rates and better functional outcomes.4–8 However, thrombolysis of stroke mimics has consequences, as recent studies on cost analysis indicate substantial financial burden.9 After IV tPA treatment, there are additional downstream costs of incorrect stroke diagnosis, including unnecessary or misguided testing, statin and antithrombotic therapy, and although rare, the risk of intracranial hemorrhage and angioedema.6,9,10

In acute stroke evaluation, a negative screening MRI triggers consideration of a stroke mimic. A negative follow-up MRI after initial CT evaluation may do the same, knowing that averted stroke on DWI is rare after IV thrombolysis.11–13 It has been proposed that patients presenting with atypical stroke symptoms at CT-based institutions may benefit from MRI evaluation before thrombolysis.10 In addition, IV tPA can be delivered within standard practice guideline DTN times with acute MRI under the Screening with MRI for Accurate and Rapid Stroke Treatment paradigm.14

We sought to compare stroke mimic treatment rates, clinical outcomes, and changes over time in patients treated at CT-based spoke hospitals and transferred to MRI-based hub hospitals with those of patients initially treated at the hubs.

METHODS

Design, setting, and participants.

This was a retrospective analysis of de-identified data from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Stroke Branch Registry, collected as part of the standard clinical pathway of the NIH stroke team with every patient encounter. This study included all consecutive adult patients with suspected acute ischemic stroke, treated with IV tPA at a hub or referring spoke hospital who were admitted to 1 of 2 hubs between January 2005 and December 2014. The 2 hub hospitals were MedStar Washington Hospital Center (Comprehensive Stroke Center) in Washington, DC, and Suburban Hospital (Primary Stroke Center) in Bethesda, Maryland. Demographics recorded included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, prior ischemic stroke, alcohol, and smoking). Race/ethnicity were adjudicated based on routine hospital patient self-reporting and included to reflect local stroke population demographics. Patients with missing variables were censored for each respective variable.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent.

Data reported in this manuscript were obtained under NIH Office of Human Subjects Research Determination (13285) of Not Human Subjects Research based on “Research Involving Coded Private Information or Biological Specimens” (Office for Human Research Protections, per October 16, 2008, revision) and Guidance on Engagement of Institutions in Human Subjects Research (per October 16, 2008, revision).

Description.

Acute evaluation and treatment at hubs were done by the NIH stroke team with multimodal MRI as the primary acute imaging modality, while at spokes, emergency medicine physicians performed the evaluation and treatment with phone guidance from a hub-based NIH stroke team vascular neurologist and noncontrast CT as the default imaging. IV tPA was administered in accordance with the current national guidelines at the time of tPA administration. Patients enrolled into a clinical trial or treated with additional endovascular therapy were excluded. Stroke was defined as a clinical syndrome consistent with acute ischemic stroke, restricted diffusion lesion with or without a perfusion deficit, and/or perfusion deficit only on multimodal MRI consistent with neurologic deficit at admission (or spoke patient transfer arrival), 2-hour, or 24-hour scan, as determined during clinical evaluation by an NIH stroke team physician. Stroke mimic was defined as clinical symptoms or neurologic deficit attributed to a noncerebrovascular etiology without MRI diagnostic of stroke and deemed unlikely to represent a cerebrovascular event (i.e., averted stroke, imaging-negative stroke) after clinical evaluation by an NIH stroke team physician. All drip-and-ship spoke patients were triaged at the hub hospital as an acute stroke code with MRI and immediate clinical evaluation by a vascular neurologist who performed an NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and assigned a preliminary admission diagnosis upon arrival (based on the clinical assessment and ancillary history). Final diagnosis for all patients was documented by the treating NIH stroke team physician at the time of hospital discharge as part of the standard clinical pathway.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis.

Stroke mimic treatment rates and associated clinical outcomes were compared between spokes and hubs. Mimic rates and clinical outcomes were compared between 2 time epochs, 2005–2009 vs 2010–2014. Demographics, OTT, stroke vs stroke mimic diagnosis, admission NIHSS, hemorrhagic transformation (parenchymal hematoma type 2 [PH-2] by European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study II criteria), and clinical outcomes (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] at 5 days or discharge and discharge location) were compared using univariate analyses.15–17 Due to spoke hospital variability in the initiation of stroke quality measures and their incomplete reporting over time, DTNs were not included in spoke analysis. IBM (Chicago, IL) SPSS Statistics v19 was used for subgroup statistics including proportions and nonparametric distribution tests.

RESULTS

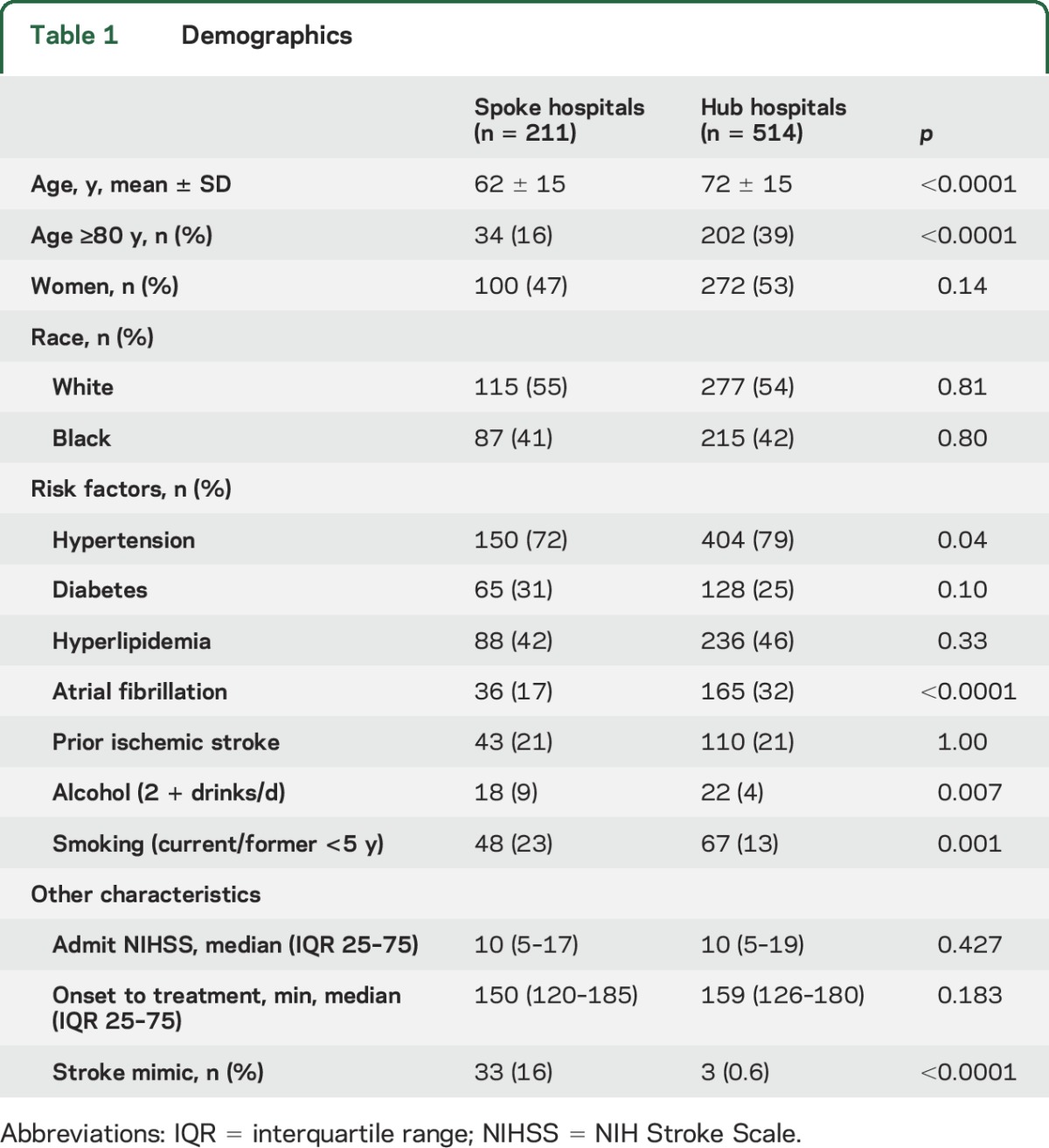

Of 725 patients, 29% received IV tPA at spokes and 71% at hubs, with similar OTTs. Spoke patients had higher rates of alcohol consumption (9% vs 4%, p = 0.007) and smoking (23% vs 13%, p = 0.001), while hub patients were significantly older (mean 72 ± 15 vs 62 ± 15, p < 0.0001) with higher rates of atrial fibrillation (32% vs 17%, p < 0.0001) and hypertension (79% vs 72%, p = 0.04) (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics

The stroke mimic rate was higher at spokes compared to hubs (16% vs 0.6%, p < 0.0001). Two of the 3 mimics treated at the hubs were CT-based evaluations. Of the 211 drip-and-ship patients, 8 (4%) had resolved neurologic symptoms (NIHSS 0) upon arrival at the hub, with 5 of the 8 imaging positive for stroke, 2 of the 8 imaging negative and classified as a probable ischemic cerebrovascular event, and only 1 of the 8 classified as a mimic.

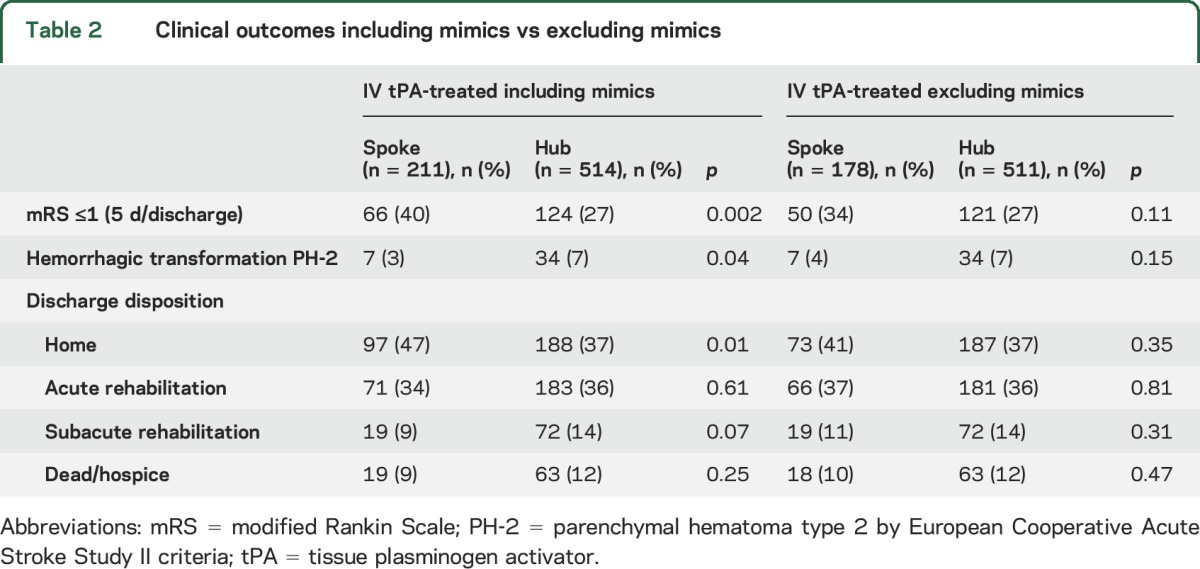

Inclusion of mimics in outcome measure analyses resulted in better outcomes for spokes vs hubs for mRS ≤1 (40% vs 27%, p = 0.002), hemorrhagic transformation (3% vs 7%, p = 0.037), and discharge to home (47% vs 37%, p = 0.01) (table 2). However, when excluding mimics, there was no difference in these outcomes for spokes vs hubs (mRS ≤1, 34% vs 27%, p = 0.11; hemorrhagic transformation 4% vs 7%, p = 0.154, discharge to home, 41% vs 37%, p = 0.35) (table 2). No mimics developed PH-2. Five-day/discharge mRS was missing on 47 (22%) spoke and 58 (11%) at hub patients. Discharge disposition outcomes were missing on 3 (0.01%) spoke patients and 1 (0.002%) hub patient.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes including mimics vs excluding mimics

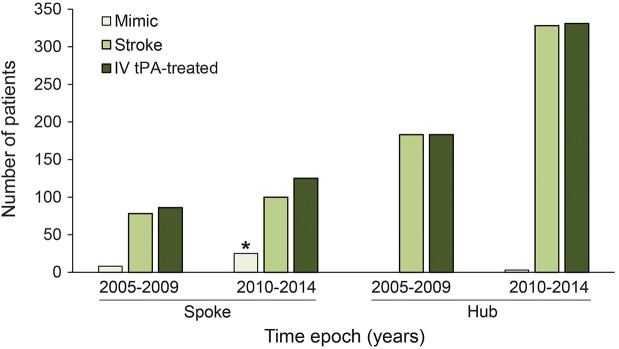

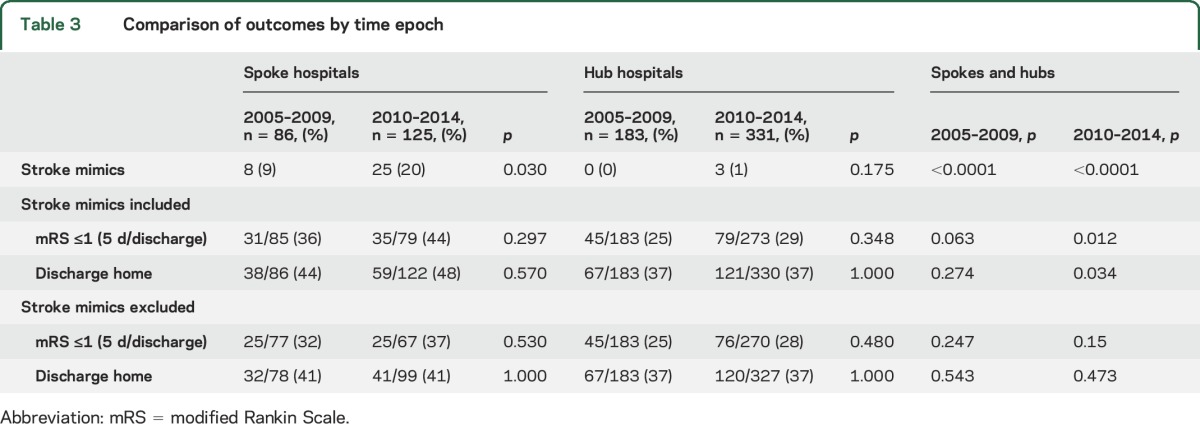

Comparing epochs 2005–2009 to 2010–2014, the stroke mimic rate at spokes doubled over time (9%–20%, p = 0.03); the hub mimic rate was unchanged (0%–1%, p = 0.175) (figure). Comparison of time epochs within spokes and hubs respectively showed no difference in outcomes of mRS ≤1 or discharge to home. However, across spokes and hubs, favorable outcomes were skewed by inclusion of stroke mimics over time, with significant differences in the later time epoch for mRS ≤1 (spokes 44% vs hubs 29%; p = 0.012) and discharge to home (spokes 48% vs hubs 37%; p = 0.034), while there were no differences over time in these outcome measures after exclusion of stroke mimics (table 3).

Figure. Spoke hospital vs hub hospital stroke mimic rate comparison over time of IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)–treated patients.

*Significant increase in stroke mimic rate at spoke hospitals between time epochs (9% vs 20%; p = 0.03).

Table 3.

Comparison of outcomes by time epoch

Median DTN at the hubs significantly decreased between time epochs: 94 minutes for 2005–2009 (interquartile range [IQR] 25–75: 74–116 minutes) compared to 76 minutes for 2010–2014 (IQR 25–75: 59–95 minutes, p < 0.000). There was no significant difference in OTT between the time epochs at either the spokes or the hubs (spokes: 155 minutes for 2005–2009 [IQR 25–75: 120–176], 147 minutes for 2010–2014 [IQR 25–75: 119–191, p = 0.682]; hubs: 164 minutes for 2005–2009 [IQR 25–75: 142–179], 153 minutes for 2010–2014 [IQR 25–75: 118–190, p = 0.264]).

DISCUSSION

Treatment of stroke mimics with IV tPA has doubled over time at our CT-based spoke hospitals while our MRI-based hubs have maintained low mimic treatment rates. When mimics were excluded, there were no differences in clinical outcomes between the spoke- and hub-treated, diagnosis-verified stroke patients, despite noted differences in baseline characteristics. While the finding of a higher percentage of mimic patients screened with CT vs MRI is not surprising, it is important to quantify and share this effect as a comparison of acute CT screening centers vs acute MRI screening centers, since clinical outcomes appear better if mimics are inadvertently included in the overall treated population.

Our finding of increased stroke mimic rates at CT-based spokes is similar to previously reported rates as high as 30% at centers screening with noncontrast head CT and actively reducing DTN times.1,3 Whether this can be attributed to the initial clinical evaluation (emergency medicine clinician vs vascular neurologist) or imaging modality remains unclear. The increase in treatment of stroke mimics is likely multifactorial, and related to initiatives to decrease DTN, inclusion of a greater number of thrombolytic-eligible patients with time window extension to 4.5 hours, acceptance of the relative safety of IV tPA treatment of stroke mimics, and an increased comfort of emergency clinicians treating with IV tPA.2,18–21 It is clear that functional outcomes of stroke mimics are better than those with actual stroke and that more mimics are being treated with faster DTN times.3,20

The increase in stroke mimic treatment rates comes at several costs. From a financial perspective, in a study of 4 primary stroke centers in Tennessee, treatment of patients with IV tPA for presumed stroke with a final diagnosis of mimic led to excess hospital costs estimated to be $257,975 for direct costs and $152,813 in indirect costs, with median excess cost per admission of $5,401, not including costs for interhospital patient transfer.9 In addition to the financial costs incurred, inaccurate diagnosis generates misperception among patients, their families, and clinicians involved in their subsequent care as to their health problems and appropriate treatment strategies and risk modifications. Continued effort toward improving initial diagnostic accuracy with the use of independent or adjunctive telestroke evaluation by a vascular neurologist and multimodal CT or MRI in cases where an ischemic event is ambiguous may be beneficial.14,22 Studies indicate that use of telestroke improves diagnostic accuracy and could prevent unnecessary thrombolysis, associated risks, and costly transfer of stroke mimics.23,24 Diagnostic accuracy should not be compromised by swift treatment and in cases where stroke diagnosis is questionable, confirmatory imaging and pursuit of alternative diagnoses is imperative, if not hyperacutely, at least prior to discharge.21 We recognize that optimization of acute MRI evaluation of stroke is not possible at many institutions, and therefore, should not be pursued at the expense of treatment delay in clear stroke cases.

This study was limited to 2 hubs in the Washington metropolitan region where 86% of patients treated with IV tPA were screened with MRI.14 Spoke patients were limited to those who were transferred to our hubs under the drip-and-ship paradigm and did not reflect the entire IV tPA-treated population at spoke hospitals (i.e., IV tPA patients who were treated without transfer). Mimic rates may be higher at spokes than those reported in our referral population due to bias of stroke rather than mimic diagnosis for IV tPA-treated patients with or without further diagnosis verification and MRI. Conversely, the hub hospital stroke clinician may be biased toward classifying a drip-and-ship patient as a mimic, rather than the rare diagnosis of averted stroke, if the patient has resolved symptoms and a negative MRI upon arrival at the hub.11–13 However, our method of acute clinical evaluation of all IV tPA-treated patients, including immediate vascular neurology assessment with MRI of spoke patients upon transfer, minimizes this potential bias. This is reflected in the fact that only 1 of 3 drip-and-ship patients with resolved symptoms and negative imaging in our study was diagnosed as a mimic. DTN times were not available for all spoke transfers, therefore DTN comparisons including any change over time were not made between spokes and hubs.

Despite its limitations, the value of this study is that, though it is important to expedite and treat acute stroke in a timely fashion, detection bias as evidenced by the inclusion of stroke mimics leads to confounding in outcome assessment. Caution should be used in interpreting clinical outcomes when stroke diagnosis is unclear, as stroke mimics artificially elevate clinical outcomes. Detailed evaluation of suspected stroke patients is needed throughout the hospitalization to improve diagnostic accuracy, ensure appropriate reporting of disease processes, and avoid unnecessary testing and treatments. Diagnostic accuracy of stroke at hospital discharge should be monitored to avoid inclusion of stroke mimics and their downstream effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The investigators thank the NIH Stroke Teams at MedStar Washington Hospital Center and Johns Hopkins Community Physicians Suburban Hospital as well as clinicians at referring spoke hospitals.

GLOSSARY

- DTN

door-to-needle

- IQR

interquartile range

- mRS

modified Rankin Scale

- NIHSS

NIH Stroke Scale

- OTT

onset-to-treatment

- PH-2

parenchymal hematoma type 2

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Drs. Hsia and Luby had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Drs. Hsia and Burton. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Drs. Hsia, Luby, and Burton. Drafting of the manuscript: Drs. Hsia and Burton. Statistical analysis: Dr. Luby. Administrative, technical, or material support: Drs. Hsia and Luby. Study supervision: Dr. Hsia. All authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of data for the work, critical revision for important intellectual content, and final approval of the submitted version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

STUDY FUNDING

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH/NINDS Section on Stroke Diagnostics and Therapeutics.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fonarow GC, Zhao X, Smith EE, et al. Door-to-needle times for tissue plasminogen activator administration and clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke before and after a quality improvement initiative. JAMA 2014;311:1632–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. New Engl J Med 2008;359:1317–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liberman AL, Liotta EM, Caprio FZ, et al. Do efforts to decrease door-to-needle time risk increasing stroke mimic treatment rates? Neurol Clin Pract 2015;5:247–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chernyshev OY, Martin-Schild S, Albright KC, et al. Safety of tPA in stroke mimics and neuroimaging-negative cerebral ischemia. Neurology 2010;74:1340–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta S, Vora N, Edgell RC, et al. Stroke mimics under the drip-and-ship paradigm. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;23:844–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen PL, Chang JJ. Stroke mimics, acute stroke evaluation: clinical differentiation and complications after intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. J Emerg Med 2015;49:244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivakumaran P, Gill D, Mahir G, Baheerathan A, Kar A. A retrospective cohort study on the use of intravenous thrombolysis in stroke mimics. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2016;25:1057–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zinkstok SM, Engelter ST, Gensicke H, et al. Safety of thrombolysis in stroke mimics: results from a multicenter cohort study. Stroke 2013;44:1080–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster A, Griebe M, Wolf ME, Szabo K, Hennerici MG, Kern R. How to identify stroke mimics in patients eligible for intravenous thrombolysis? J Neurol 2012;259:1347–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyal N, Male S, Al Wafai A, Bellamkonda S, Zand R. Cost burden of stroke mimics and transient ischemic attack after intravenous tissue plasminogen activator treatment. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;24:828–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell BC, Purushotham A, Christensen S, et al. The infarct core is well represented by the acute diffusion lesion: sustained reversal is infrequent. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012;32:50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chemmanam T, Campbell BC, Christensen S, et al. Ischemic diffusion lesion reversal is uncommon and rarely alters perfusion-diffusion mismatch. Neurology 2010;75:1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman JW, Luby M, Merino JG, et al. Negative diffusion-weighted imaging after intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator is rare and unlikely to indicate averted infarction. Stroke 2013;44:1629–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah S, Luby M, Poole K, et al. Screening with MRI for accurate and rapid stroke treatment: SMART. Neurology 2015;84:2438–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiorelli M, Bastianello S, von Kummer R, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation within 36 hours of a cerebral infarct: relationships with early clinical deterioration and 3-month outcome in the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study I (ECASS I) cohort. Stroke 1999;30:2280–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke: The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS). JAMA 1995;274:1017–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II): Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet 1998;352:1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown MD, Burton JH, Nazarian DJ, Promes SB. Clinical policy: use of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for the management of acute ischemic stroke in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:322–333.e331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cronin CA, Langenberg P, Dutta TM, Kittner SJ. Transition of European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III results to clinical practice: ninety-day outcomes in a US cohort. Stroke 2013;44:3544–3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillan M, Alonso-Canovas A, Gonzalez-Valcarcel J, et al. Stroke mimics treated with thrombolysis: further evidence on safety and distinctive clinical features. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;34:115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saver JL, Barsan WG. Swift or sure? The acceptable rate of neurovascular mimics among IV tPA-treated patients. Neurology 2010;74:1336–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell BC, Weir L, Desmond PM, et al. CT perfusion improves diagnostic accuracy and confidence in acute ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84:613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaghi S, Rayaz S, Bianchi N, Hall-Barrow JC, Hinduja A. Thrombolysis to stroke mimics in telestroke. J Telemed Telecare Epub 2012 Oct 3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Meyer BC, Raman R, Hemmen T, et al. Efficacy of site-independent telemedicine in the STRokE DOC trial: a randomised, blinded, prospective study. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]