By using linked nationwide registry data from Denmark, we characterize the impacts of birth season and birth year on patterns of antibiotic prescribing during infancy.

Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

We examined 2 birth cohort effects on antibiotic prescribing during the first year of life (henceforth, infancy) in Denmark: (1) the birth season effect on timing and overall occurrence of antibiotic prescribing, and (2) the birth year effect amid emerging nationwide pneumococcal vaccination programs and changing prescribing guidelines.

METHODS:

We linked data for all live births in Denmark from 2004 to 2012 (N = 561 729) across the National Health Service Prescription Database, Medical Birth Registry, and Civil Registration System. Across birth season and birth year cohorts, we estimated 1-year risk, rate, and burden of redeemed antibiotic prescriptions during infancy. We used interrupted time series methods to assess prescribing trends across birth year cohorts. Graphical displays of all birth cohort effect data are included.

RESULTS:

The 1-year risk of having at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy was 39.5% (99% confidence interval [CI]: 39.3% to 39.6%). The hazard of a first prescription increased with age throughout infancy and varied by season; subsequently, Kaplan-Meier–derived risk functions varied by birth season cohort. After rollout of a first vaccination program and new antibiotic prescribing guidelines, 1-year risk decreased by 4.4% over 14 months (99% CI: 3.4% to 5.5%); it decreased again after rollout of a second vaccination program by 6.9% over 3 years (99% CI: 4.4% to 9.3%).

CONCLUSIONS:

In Denmark, birth season and birth year cohort effects influenced timing and risk of antibiotic prescribing during infancy. Future studies of antibiotic stewardship, effectiveness, and safety in children should consider these cohort effects, which may render some children inherently more susceptible than others to downstream antibiotic effects.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Widespread antibiotic use leads to bacterial resistance, and unnecessary antibiotic use in early life may cause excess immune dysfunction in childhood. Antibiotic prescribing is influenced by seasonal and temporal factors, but data are limited regarding cohort effects on antibiotic use in children.

What This Study Adds:

In this study, we characterize birth season and birth year cohort effects on antibiotic prescribing during infancy, which merit consideration in pediatric studies of antibiotic stewardship, effectiveness, and safety. We also provide new information on correlation between risk, rate, and burden of antibiotic prescribing.

During early life, children are often prescribed antibiotics for bacterial infections. Approximately 20% to 50% of children’s antibiotic prescriptions are used to treat nonbacterial upper respiratory tract infections,1–3 for which they are largely ineffective.2,4–6 In Western industrialized countries in particular, increasing advocacy for rational antibiotic prescribing has been associated with decreased population-level antibiotic use.7–10 In addition, pneumococcal conjugate vaccination (PCV) programs have been associated with decreased risk of acute otitis media and lower respiratory tract infections,11 2 of the most common indications for antibiotics in children.4,12–16 Taken together, there is a need to better characterize the changing patterns of antibiotic prescribing in children.

Previous studies of trends in early life antibiotic prescribing have focused on rates in cross-sectional population samples,3,8,9,17–23 counting multiple prescriptions per child and tending to present results for coarse age groups (eg, 0–4 years) or groups defined by the year or season when they were observed (eg, during winter 2010). In addition, studies of rates implicitly estimate the frequency of providers prescribing or dispensing antibiotics to groups of children; however, studies of risk aggregate individual-level data to clarify which well-defined cohorts of children receive or redeem a given number of prescriptions over a specific follow-up interval. Currently, data are limited regarding cohort effects on the risk of overall and medication-specific antibiotic use during early childhood.

In Denmark, recent policy and guideline changes may have induced changes in antibiotic prescribing. The Danish Health and Medicine Authority’s Institute for Rational Pharmacotherapy (IRF), a government institute, issued a bulletin in 2007 with rational antibiotic prescribing guidelines.24 In 2007, the Danish childhood vaccination program introduced the 7-valent PCV (PCV7), replacing it with the 13-valent PCV (PCV13) in 2010.25–27 No studies have evaluated the impact of these events on antibiotic prescribing in Denmark during the first year of life (henceforth, infancy).

Our objectives were to estimate birth season cohort effects on antibiotic prescribing during infancy in Denmark, and birth year cohort effects on antibiotic prescribing potentially brought about by the IRF bulletin and PCV programs.

Methods

This cohort study included all live births in Denmark from 2004 to 2012, identified by using the Danish Medical Birth Registry (MBR), which has registered all live births in Denmark since 1973.28 We used each child’s unique 10-digit personal registration number to link their individual-level data across multiple registries. After excluding children with inconsistent identification information (Supplemental Information), we examined the remaining cohort from birth for 365 days or until death or emigration.

To identify birth cohorts, we grouped children by week, month, season (winter: December to February; spring: March to May; summer: June to August; autumn: September to November), and year of birth. We ascertained demographic information from the MBR and Civil Registration System29 and used the MBR to identify clinical characteristics of the mother, pregnancy, and birth event.

Data on Antibiotics

The Danish National Health Service Prescription Database contains nationwide records for all prescriptions redeemed in community pharmacies and hospital-based outpatient pharmacies onward from 2004.30 We used Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) J01 codes to identify prescriptions for systemic antibiotics redeemed from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2013, and classified antibiotics by chemical substance (henceforth, medication).

Risk, Rate, and Burden of Antibiotic Prescribing

To examine differences by birth year cohort in overall and medication-specific prescribing, we estimated 3 measures of antibiotic prescribing: (1) 1-year risk of at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy by using Kaplan-Meier methods to account for censoring at death or emigration; (2) incidence rate of redeemed antibiotic prescriptions, allowing for multiple redeemed prescriptions per infant (henceforth, rate); and (3) 1-year burden of antibiotic prescriptions, on the basis of the total days supplied for redeemed antibiotic prescriptions throughout infancy. For rate and burden, we also computed each medication’s share of overall prescribing, ie, the proportion of all antibiotic prescriptions (for the rate) or all days supplied (for the burden).

Birth Season Cohort Effect on Time to First Redeemed Antibiotic Prescription

We assessed the impact of birth season on age at first redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy by using Kaplan-Meier methods to account for censoring at death or emigration. Infants were stratified by birth season cohort and assessed using age as the time scale. We estimated the hazard (ie, instantaneous risk) function for first redeemed antibiotic prescription and the Kaplan-Meier–derived risk function over 1 year for having at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy.

Interrupted Time Series Analysis

To estimate trend changes in antibiotic prescribing over time, we used segmented linear regression analysis of interrupted time series data,31–34 a common quasi-experimental method to assess trend changes after clearly defined events. Separately for each birth week cohort, we estimated the 1-year risk of redeeming at least 1 prescription for any antibiotic, with subanalyses for amoxicillin and penicillin V.

We identified 5 time-based interruptions when a population-level change in Denmark could have altered antibiotic prescribing in infants born before versus after the interruption (Table 1). We negatively lagged all interruptions to match each policy or guideline change with the infants subject to its potential impact. To control confounding by seasonality in our segmented linear regression model, we used a transformed cosine periodic function.35–37 Between any 2 interruptions, the trend estimate (ie, the change in 1-year risk during that specific time interval) resulted from the accumulation of the baseline trend and the effect of each policy or guideline change on the underlying trend. For example, for segment #3 (July 1, 2007, until January 19, 2010) the estimate was equal to the baseline trend plus the trend changes occurring at interruptions 1 and 2 (Supplemental Information).

TABLE 1.

Interruption Time Points for Hypothesized Population-Level Changes in Denmark Related to Antibiotic Use Among Infants

| Interruption | Date of Publication or Rollout | First Birth Cohort to Experience Potential Interruption Effect (Negatively Lagged) | Intended Effect and Description of Interrupting Policy or Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRF bulletin | April 1, 2007 | April 1, 2006 | Nationwide bulletin to advocate rational antibiotic prescribing among GPs. It stated that antibiotics nominally affect the duration of acute otitis media infection and do not prevent adverse sequelae (eg, mastoiditis or recurrent acute otitis media). For antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children, it recommended primary treatment with penicillin V, a narrow-spectrum antibiotic38; after penicillin V failure, the secondary recommendation was for amoxicillin,24 which has a broader spectrum of antibacterial activity than penicillin V.38 |

| PCV7 “catch-up” program | October 1, 2007 | May 1, 2006 | Danish childhood vaccination program granted cost-free enrollment in PCV7 program for children between 3 and 17 mo of age. Vaccination is intended to reduce incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease, pneumococci-related upper and lower respiratory infection, and transition of pneumococci in the general population. Children in this group who received their first PCV7 vaccination before their first birthday were offered a second PCV7 course after a minimum 1-mo interval and a third after 2 more months minimum. Children who received their first course after their first birthday were offered 1 additional course after a minimum 2-mo interval.25–27 |

| Standard PCV7 program | October 1, 2007 | July 1, 2007 | Danish childhood vaccination program granted cost-free enrollment in PCV7 program for children <3 mo of age on October 1, 2007, onward. A series of 3 PCV7 courses at 3, 5, and 12 mo of age, concurrent with the DTaP/IPV/Hib vaccination.25–27 |

| Transition from PCV7 to PCV13 | April 19, 2010 | January 19, 2010 | Danish childhood vaccination program granted cost-free enrollment in PCV13 program for children <3 mo of age on April 19, 2010, onward; however, the program recommended using all PCV7 stocks before initiating PCV13. PCV13 dissemination was therefore gradual during 2010.27 |

| Standard PCV13 program | January 1, 2011 | October 1, 2010 | Danish childhood vaccination program granted cost-free enrollment in PCV13 program for children <3 mo of age. After gradual depletion of PCV7 stocks during 2010, PCV13 was predominant nationwide by 2011.27 |

DTaP/IPV/Hib, diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, polio, and Haemophilus influenzae type b.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated rates and burdens with corresponding 99% confidence intervals (CIs), risks with 99% pointwise CIs, and all trend estimates with 99% CIs. Hazard functions were smoothed by using a 20th-order polynomial function and plotted with 99% confidence bands. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC), and graphics were created by using R version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

This study received ethics approval from the Danish Data Protection Agency (2013-41-1790), Danish Statens Serum Institut (FSEID-00001450), and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (13-3155).

Results

The final study population included 561 729 live births in Denmark occurring from 2004 to 2012. Antibiotic prescriptions accounted for 46.0% of all drug prescriptions redeemed during infancy; among 333 298 infants with a redeemed prescription for any drug, 66.2% had at least 1 antibiotic prescription.

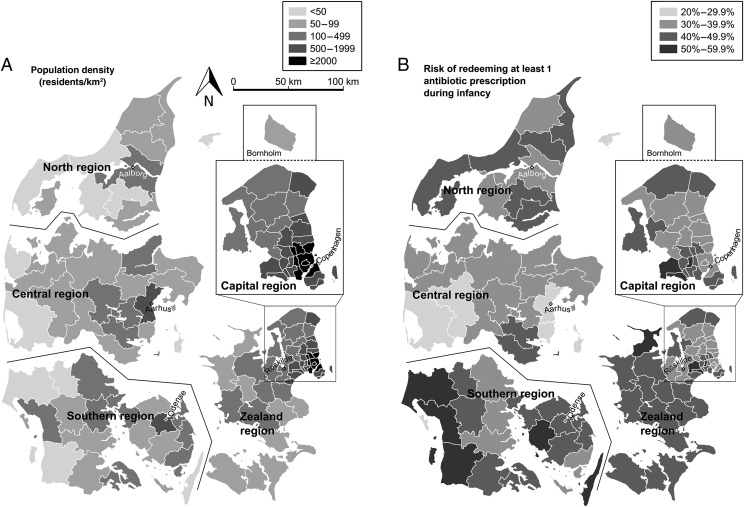

In Table 2, we report descriptive data for the study population along with subgroup-specific estimates of the 1-year risk for having at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy. The overall 1-year risk was 39.5% (99% CI: 39.3% to 39.6%). Boys had a higher risk than girls, first-born children had a lower risk than younger siblings, and risk decreased with increasing maternal age. Maternal smoking, pregravid BMI, and prenatal clinic visit frequency were associated with higher risk. Risk increased with increasing birth weight but was not associated with gestational age. Children whose mother requested cesarean delivery had a higher risk than the general population. Geographically, risk was highest in Zealand and Southern Denmark and lowest in Central Denmark; higher population density was associated with lower risk (Fig 1).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Children Born in Denmark During 2004–2012 and Subgroup-Specific 1-Year Risks of Antibiotic Prescription During Infancy

| Total Study Population (N = 561 729) | Children With ≥1 Redeemed Antibiotic Prescription During Infancy (n = 220 655, 39.3%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%a) | No. | Subgroup-Specific 1-y Risk, % (99% CI)b | |

| Demographics | |||

| Sex of child | |||

| Female | 273 839 (48.7) | 97 357 | 35.7 (35.5 to 36.0) |

| Male | 287 890 (51.3) | 123 298 | 43.0 (42.8 to 43.3) |

| Mother’s age at birth (y) | |||

| <25 | 59 371 (10.6) | 25 847 | 43.8 (43.3 to 44.3) |

| 25–29.9 | 167 819 (29.9) | 67 901 | 40.6 (40.3 to 41.0) |

| 30–34.9 | 213 324 (38.0) | 83 469 | 39.3 (39.0 to 39.6) |

| 35–39.9 | 100 886 (18.0) | 36 775 | 36.6 (36.2 to 37.0) |

| ≥40 | 20 329 (3.6) | 6663 | 32.9 (32.1 to 33.8) |

| Season of birth | |||

| Winter (December, January, February) | 132 235 (23.5) | 52 120 | 39.6 (39.3 to 40.0) |

| Spring (March, April, May) | 139 639 (24.9) | 62 305 | 44.8 (44.5 to 45.2) |

| Summer (June, July, August) | 149 743 (26.7) | 58 457 | 39.2 (38.9 to 39.5) |

| Autumn (September, October, November) | 140 112 (24.9) | 47 773 | 34.3 (33.9 to 34.6) |

| Year of birth | |||

| 2004–2006 | 192 572 (34.3) | 79 957 | 41.7 (41.4 to 42.0) |

| 2007–2009 | 190 580 (33.9) | 74 388 | 39.2 (38.9 to 39.5) |

| 2010–2012 | 178 577 (31.8) | 66 310 | 37.3 (37.0 to 37.6) |

| Region of birth | |||

| Capital region | 190 832 (34.0) | 73 926 | 39.0 (38.7 to 39.3) |

| Zealand region | 70 089 (12.5) | 31 953 | 45.7 (45.2 to 46.2) |

| Southern region | 112 140 (20.0) | 49 422 | 44.2 (43.9 to 44.6) |

| Central region | 137 420 (24.5) | 45 891 | 33.5 (33.2 to 33.8) |

| North region | 51 248 (9.1) | 19 463 | 38.1 (37.6 to 38.7) |

| Pregnancy and birth | |||

| Parity (live births and stillbirths)c | |||

| First pregnancy | 246 191 (44.5) | 85 570 | 34.9 (34.7 to 35.2) |

| Second | 203 881 (36.8) | 88 248 | 43.4 (43.2 to 43.7) |

| Third | 76 312 (13.8) | 31 785 | 41.8 (41.4 to 42.3) |

| Fourth or more | 27 002 (4.9) | 11 627 | 43.3 (42.5 to 44.1) |

| No. of pregnancy visits to a GP | |||

| 0 | 87 968 (15.7) | 32 396 | 37.0 (36.6 to 37.4) |

| 1–2 | 102 994 (18.3) | 40 147 | 39.3 (38.9 to 39.7) |

| ≥3 | 370 767 (66.0) | 148 112 | 40.1 (39.9 to 40.3) |

| No. of pregnancy visits to midwife | |||

| 0 | 44 398 (7.9) | 16 016 | 36.4 (35.8 to 37.0) |

| 1–2 | 21 075 (3.8) | 7832 | 37.9 (37.0 to 38.7) |

| ≥3 | 496 256 (88.3) | 196 807 | 39.8 (39.6 to 40.0) |

| No. of pregnancy visits to ob-gyn | |||

| 0 | 466 761 (83.1) | 181 215 | 39.0 (38.8 to 39.2) |

| 1–2 | 57 429 (10.2) | 23 287 | 40.7 (40.2 to 41.2) |

| ≥3 | 37 539 (6.7) | 16 153 | 43.2 (42.6 to 43.9) |

| Mother’s pregravid BMI (kg/m2)c | |||

| <18.5 | 27 034 (5.1) | 9866 | 36.7 (36.0 to 37.5) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 326 332 (61.8) | 122 260 | 37.6 (37.4 to 37.9) |

| 25–29.9 | 111 711 (21.1) | 46 204 | 41.5 (41.1 to 41.9) |

| ≥30 | 63 267 (12.0) | 28 179 | 44.7 (44.2 to 45.2) |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancyc | |||

| Did not smoke | 470 150 (85.7) | 180 423 | 38.6 (38.4 to 38.7) |

| Quit during pregnancy | 14 048 (2.6) | 5739 | 41.0 (40.0 to 42.1) |

| Smoking, ≤10 cigarettes/d | 43 293 (7.9) | 19 461 | 45.1 (44.5 to 45.7) |

| Smoking, >11 cigarettes/d | 19 749 (3.6) | 9143 | 46.4 (45.5 to 47.4) |

| Smoking, amount not reported | 1542 (0.3) | 680 | 44.4 (41.2 to 47.7) |

| Gestational age at birth (wk)c | |||

| <37 | 36 637 (6.5) | 13 833 | 38.3 (37.7 to 39.0) |

| 37–39.9 | 235 805 (42.1) | 95 142 | 40.5 (40.3 to 40.8) |

| ≥40 | 287 561 (51.3) | 111 049 | 38.8 (38.5 to 39.0) |

| Birth weight (g)c | |||

| <2500 | 28 767 (5.2) | 10 107 | 35.8 (35.1 to 36.5) |

| 2500–3499 | 242 598 (43.5) | 93 304 | 38.6 (38.4 to 38.9) |

| 3500–4499 | 269 026 (48.2) | 108 281 | 40.4 (40.1 to 40.6) |

| ≥4500 | 17 775 (3.2) | 7656 | 43.2 (42.2 to 44.2) |

| Cesarean delivery for this birth | 123 250 (21.9) | 49 693 | 40.6 (40.2 to 41.0) |

| Cesarean by maternal request | 15 695 (2.8) | 6956 | 44.4 (43.4 to 45.5) |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 45 183 (8.0) | 16 362 | 36.4 (35.8 to 37.0) |

| Suture to repair birth injury | 210 068 (37.4) | 80 307 | 38.4 (38.1 to 38.6) |

| Newborn transferred to NICU | 51 964 (9.3) | 20 183 | 39.3 (38.8 to 39.9) |

| Respiratory aid in NICU | 23 754 (4.2) | 8952 | 38.6 (37.8 to 39.4) |

| Sepsis during first month of life | 8989 (1.6) | 3417 | 39.1 (37.8 to 40.5) |

| Congenital malformation | 40 733 (7.3) | 17 528 | 43.6 (42.9 to 44.2) |

| Died during first year of life | 1073 (0.2) | 68 | 55.9 (38.1 to 75.3) |

| Emigrated during first year of life | 2807 (0.5) | 327 | 26.0 (22.3 to 30.2) |

Column percentages for characteristics in the total study population, which sum to 100%.

Risk estimates are each subgroup’s cumulative incidence for at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy, accounting for censoring at death or emigration; these risk estimates resemble the number of children with ≥1 prescription ÷ the number of children in the subgroup because death and emigration were rare. Risks do not sum to 100%.

Missing data occurred for parity (1.5% of children had missing values), maternal pregravid BMI (5.9%), maternal smoking during pregnancy (2.3%), gestational age at birth (0.3%), and birth weight (0.6%).

FIGURE 1.

Geographic variation in population density and antibiotic prescribing during infancy among children born in Denmark from 2004 to 2012. A, Population density by municipality, taken from census data issued for January 1, 2012 (available from Statistics Denmark, http://www.StatBank.dk/bev22). B, One-year risk of redeeming at least 1 antibiotic prescription during infancy, by municipality and region. Municipalities (n = 98) and regions (n = 5) were assigned on the basis of the location of residence after birth. Artificial gaps separate the North, Central, and Southern regions; the detailed inset for the Capital region includes the island of Bornholm (to scale), located 160 km east-southeast of Copenhagen. Each region’s capital city is labeled and marked by a diamond.

The overall rate was 72 redeemed antibiotic prescriptions per 100 infant years of follow-up, and the overall burden was 67 daily doses per 10 000 infant days (Table 3). Amoxicillin and penicillin V accounted for 89% of redeemed antibiotic prescriptions out of 22 antibiotic medications prescribed to the study population. One-year risks and rates decreased over time; however, because of increasingly concentrated prescribing to infants with at least 1 prescription, antibiotic burden among infants remained stable over time, ranging from 61 to 75 daily doses per 10 000 infant days (Supplemental Tables 4–6). Over time, the share of the overall antibiotic rate and burden over time increased for amoxicillin and decreased for penicillin V.

TABLE 3.

Redeemed Antibiotic Prescriptions by ATC Code Among Infants Born in Denmark, 2004–2012 (N = 561 729)

| ATC Level 5 (Medication) | ATC Level 4 (Subgroup) | Children With ≥1 Redeemed Antibiotic Prescription During Infancy | All Redeemed Antibiotic Prescriptions (Allowing Multiple per Infant) | Days Supplied of Antibiotic Medication (Allowing Multiple Prescriptions per Infant) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Risk (%)a | No. | Rateb | Share (%)c | Days Supplied | Burdend | Share (%)e | ||

| All antibiotics | All antibiotics | 220 655 | 39.3 | 403 886 | 72 | 100.0 | 1 368 589 | 67 | 100.0 |

| Amoxicillin | Extended spectrum penicillins | 144 104 | 25.8 | 223 999 | 40 | 55.5 | 844 466 | 41 | 61.7 |

| Penicillin V | β-lactamase sensitive penicillins | 104 609 | 18.7 | 133 622 | 24 | 33.1 | 341 838 | 17 | 25.0 |

| Amoxicillin clavulanate | Combinations of penicillins | 7541 | 1.3 | 10 694 | 2 | 2.6 | 48 539 | 2 | 3.5 |

| Trimethoprim | Trimethoprim | 1362 | 0.2 | 2555 | 0 | 0.6 | 6643 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Erythromycin | Macrolides | 14 797 | 2.6 | 18 240 | 3 | 4.5 | 79 750 | 4 | 5.8 |

| Clarithromycin | Macrolides | 6024 | 1.1 | 7074 | 1 | 1.8 | 26 142 | 1 | 1.9 |

| Azithromycin | Macrolides | 3363 | 0.6 | 4127 | 1 | 1.0 | 8496 | 0 | 0.6 |

Data not shown for other antibiotics because of small numbers: ampicillin, pivampicillin, pivmecillinam, dicloxacillin, flucloxacillin, cefuroxime, meropenem, sulfamethizole, roxithromycin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, vancomycin, colistin, fusidic acid, and nitrofurantoin.

Risk estimates reflect medication-specific cumulative incidence of at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription for during infancy on the basis of the complement of the Kaplan-Meier survival function, which accounted for censoring at death or emigration; the sum of medication-specific risks exceeds overall antibiotic risk because infants could redeem prescriptions for >1 type of antibiotic medication in their first year.

Rate = no. of redeemed prescriptions per 100 infant years of follow-up.

Share of antibiotic rate = (no. of redeemed prescriptions) ÷ (total no. of redeemed prescriptions for all antibiotics).

Population-level antibiotic drug burden = days supply per 10 000 infant days of follow-up.

Share of antibiotic burden = (days supply) ÷ (total days supply for all antibiotics).

Birth Season Cohort and Time to First Redeemed Antibiotic Prescription During Infancy

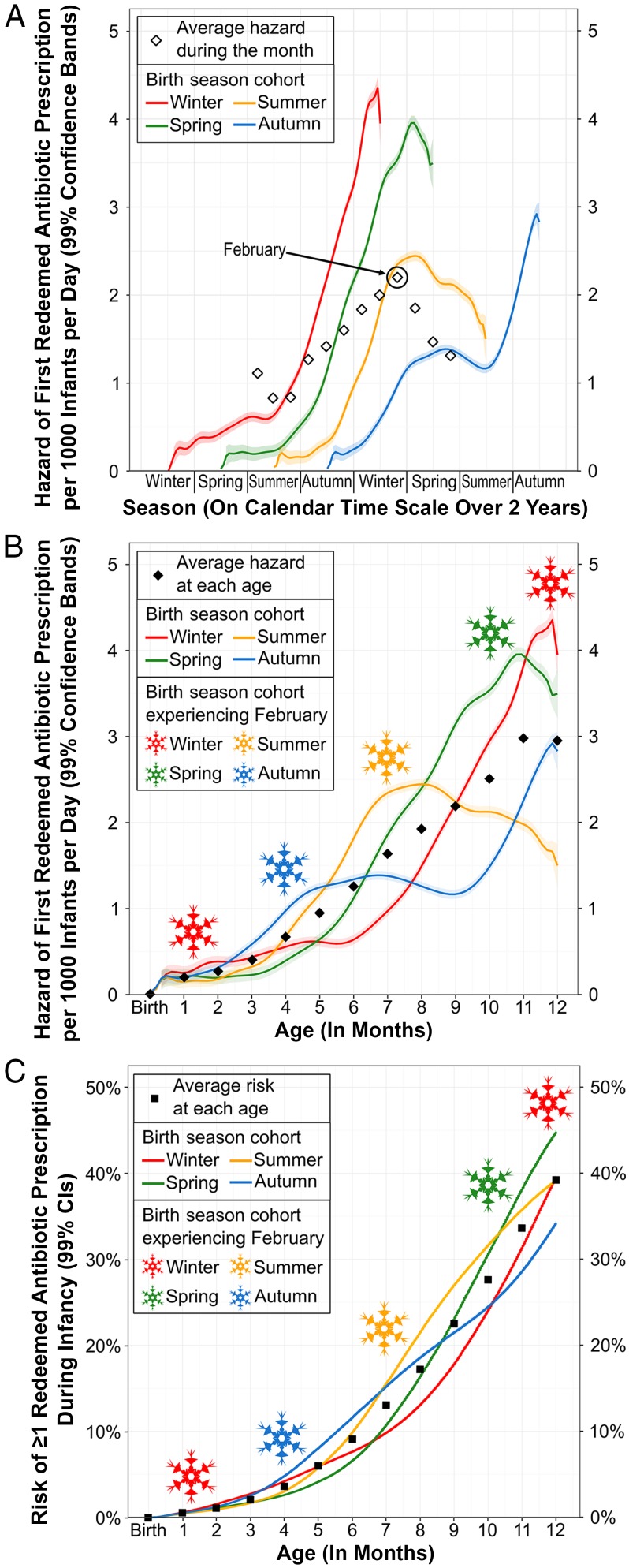

In Fig 2, we illustrate the joint effects of birth season cohort, seasonality of prescribing, and age on the time to first redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy. Each birth season cohort experienced a unique order of the seasons during infancy (eg, winter-spring-summer-autumn versus summer-autumn-winter-spring), inducing intractable age differences between birth season cohorts in any given season of the year (Fig 2A). The hazard (ie, instantaneous risk) of a first redeemed antibiotic prescription varied with the seasons and peaked in February (white diamonds in Fig 2A, snowflakes in Fig 2B). Hazard also increased with increasing age through infancy (Fig 2B, black diamonds), thus leading hazard functions to differ by birth season cohort.

FIGURE 2.

Hazard and risk functions for antibiotic prescribing during infancy by birth season cohort in Denmark from 2004 to 2012. A, Hazard functions for a first redeemed antibiotic prescription by season of calendar time among infants grouped by birth season cohort (winter: December to February; spring: March to May; summer: June to August; autumn: September to November). White diamonds show the average hazard, for all infants combined, during each month on the calendar time scale; to avoid redundancy, average monthly hazards are plotted once. B, Hazard functions for a first redeemed antibiotic prescription by age, in months, among infants grouped by birth season cohort. Black diamonds show the average hazard for all infants combined at each month of age. Snowflake colors indicate the birth season cohort experiencing February (ie, peak hazard), which occurs at different ages for different birth season cohorts. C, Risk functions for at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription by age, in months, among infants grouped by birth season cohort. Black squares show the average risk of at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription for all infants combined at each month of age. Snowflakes same as in panel B.

Each birth season cohort consequently had a unique risk function for having at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy (Fig 2C). Interpreting risk comparisons between birth season cohorts therefore depends partly on age. For example, at 6 months of age, infants born in autumn had 4.9% (bootstrapped 99% CI: 4.7% to 5.2%) higher risk than infants born in spring (11.5% vs 6.5%). At 12 months, the effect reversed such that infants born in autumn had 10.6% (bootstrapped 99% CI: 10.1% to 11.0%) lower risk than those born in spring (34.2% vs 44.8%).

Interrupted Time Series Analysis

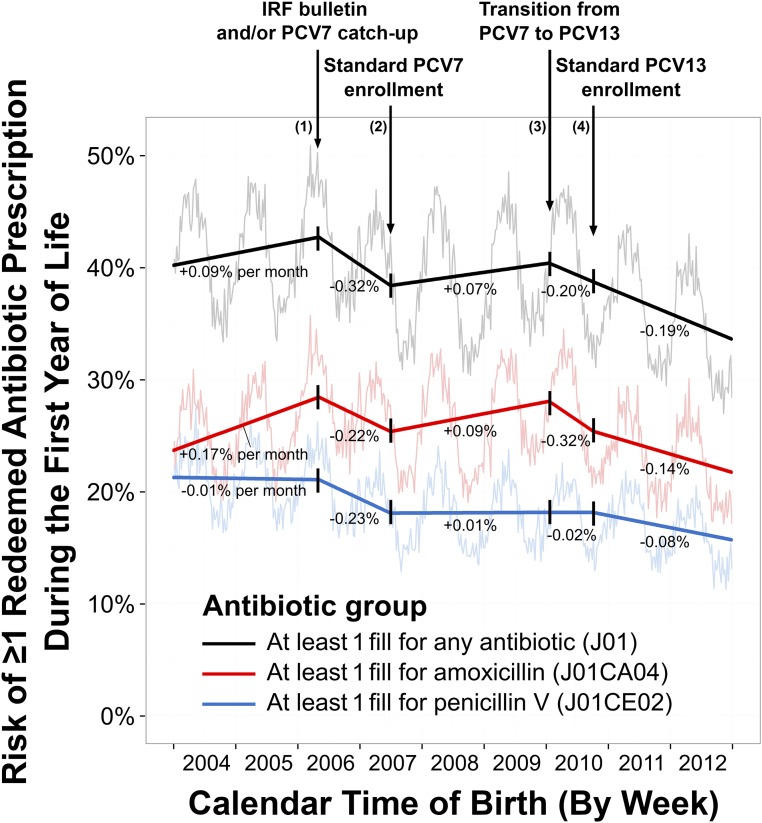

In Fig 3, we show 1-year risk and birth season–adjusted trend estimates from our interrupted time series analysis. The overall 1-year risk of having at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription decreased from 40.7% (births in 2004) to 34.6% (births in 2012). Amoxicillin risk increased by 4.8% (99% CI: 3.7% to 5.9%) from January 2004 to April 2006, but penicillin V risk remained stable. After rollout of the PCV7 “catch-up” vaccination program and publication of the IRF bulletin, overall risk decreased by 4.4% over 14 months (99% CI: 3.4% to 5.5%), decreasing equally for amoxicillin and penicillin V. After standard PCV7 enrollment began, increasing amoxicillin prescribing drove increases in overall prescribing. After the childhood vaccination program’s replacement of PCV7 with PCV13, overall risk decreased by 6.9% over 3 years (99% CI: 4.4% to 9.3%). Penicillin V prescribing changed little for children born after mid-2007 but decreased after standard PCV13 enrollment began. The effects of the bulletin and vaccination programs were 1 order of magnitude smaller than birth season cohort effects (Supplemental Table 7).

FIGURE 3.

Segmented trend estimates across calendar time birth cohorts for the 1-year risk (%) of having at least 1 redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy in Denmark from 2004 to 2012. Trends across birth cohorts (bold lines) and pointwise birth week-specific risks (faded) are shown for any antibiotic (black), amoxicillin (red), and penicillin V (blue). Interruptions are denoted by downward arrows. Trend estimates are listed for each segment as the change in 1-year risk (%) per month of birth, and are adjusted for seasonality by using a transformed cosine periodic function.

A sensitivity analysis, which added a 7-month lag to relax assumptions about the timing and duration of the effects of the bulletin and the PCV7 catch-up program, affected the trend for amoxicillin but not for penicillin V (Supplemental Information). After remaining level during the lag through January 1, 2007, the amoxicillin trend decreased precipitously through July 1, 2007, by 0.58% per month (99% CI: 0.79% to 0.37%). Trend interpretation did not change in all other sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Information).

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study of children born in Denmark, we observed decreases over time from 2004 to 2012 in the proportion of infants who received antibiotics and the overall rate of antibiotic prescriptions per infant year. For those infants who received antibiotics, there was a less pronounced decrease in the rate over time, accompanied by an increase over time in days supplied. Taken together, the increasing concentration of antibiotic prescribing in a shrinking proportion of the infant population resulted in little change over time in overall antibiotic burden. Amoxicillin, which has a more extended spectrum of antibacterial activity than penicillin V, became increasingly prominent over time. We observed that infants’ first antibiotic prescriptions occurred more frequently with increasing age and during the winter months. As a result, the association between birth season and risk of having a redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy depended partly on age. In our interrupted time series analysis, we found that 1-year risk of at least 1 redeemed amoxicillin prescription was dynamic, decreasing after the IRF bulletin and the PCV7 catch-up program, and again after rollout of the PCV13 program.

Our risk and rate estimates corroborate previous findings from substantially smaller studies on antibiotic prescribing among infants in Europe.20,39 Previous studies8,9,17–21 of antibiotic prescribing have focused on estimating rates. We used granularly defined time scales to provide new information on overall and medication-specific antibiotic prescribing patterns, seasonal effects, and secular trends. We described rates (prescriptions ÷ person time) and burden (days supplied ÷ person time) but focused primarily on estimating risks. Risks provide aggregated information about individual infants with and without redeemed antibiotic prescriptions by posing the question, “in a well-defined cohort, which children had a redeemed antibiotic prescription in their first year, and when was their first prescription redeemed?” In contrast, rate and burden estimates require additional assumptions40,41 and tend to shift the research focus to a less strictly defined group, by asking, “how many prescriptions (or days supplied) were redeemed for children in a given subgroup, defined by calendar time or another characteristic?” We recognize that each of these questions has merit depending on the setting; however, if an investigator wishes to assess individual-level determinants of antibiotic prescribing, then the risk estimator is of primary importance.

Our results for birth season cohort effects corresponded with patterns of acute otitis media, a prominent indication for antibiotic treatment, which peaks in winter and for children >6 months old.12 Researchers for two previous studies18,19 have considered seasonal differences in antibiotic prescribing in children, also showing peak prescribing in winter. However, because those studies focused on rates, interpreting seasonality was tied to time periods of peak usage rather than to intrinsically different cohorts of children (ie, birth season cohorts). Other prominent studies of antibiotic prescribing in children1,9,17,20,39 have not included explicit assessments of seasonal differences.

These new findings on birth season cohort effects inform future researchers focused on antibiotics as the exposure in 2 ways: (1) antibiotic exposure status might differ meaningfully between children born in different seasons, and (2) birth season differences in age at first antibiotic use might modify intended or unintended effects of antibiotic treatment given some children’s increased vulnerability to microbial insults in early life.42,43

This is the first study in which the impact of the IRF bulletin (in 2007) and PCV programs (from 2007 onward) on pediatric antibiotic prescribing patterns in Denmark is explicitly evaluated. Ecologic data on PCV receipt among children in Denmark have revealed evidence of sharp increases in coverage from ∼50% (children born in 2006) to sustained levels >85% for children born from 2007 to 2012.44–46 PCV programs have been associated with marked decreases in invasive pneumococcal disease in Danish children.47 Our results therefore provide potential evidence of a downstream effect of vaccination on antibiotic dispensing brought about by decreases in the proportion of children presenting with bacterial infections requiring antibiotic treatment.

It is unclear why amoxicillin trended upward after implementation of the standard PCV7 program. Potential explanations include (1) changes in circulating illnesses from 2007 to 2010, particularly among children born in late 2009 whose elevated risk appears unique compared with the overall trend in the 2 previous years; (2) a temporary minimum threshold effect32 from 2007 to 2008; and (3) limited impact of PCV7 on infection prevention.

The delayed decrease in the trend for amoxicillin after allowing a 7-month lag could result from a stronger lagged (versus immediate) effect of the bulletin or the PCV7 catch-up program, or both. If the bulletin caused the lagged decrease, then it would have affected children born after January 1, 2007, more than those born earlier. This would signify a larger effect on infants <3 months old when the bulletin was published compared with infants who were 3 to 12 months old at that time. Given that hazard increased with age during infancy, a discernible impact of the bulletin would likely have occurred some months after it was published. At the same time, a strong lagged effect of the PCV7 catch-up program would be plausible if the standard PCV7 program had been associated with decreasing risk. Researchers for future studies should assess infection trends and antibiotic prescribing patterns after 2012, to examine the potential ongoing effect of the PCV program.

This study has limitations to consider when interpreting results. We lacked data on indication because general practitioners (GPs) (who are not mandated to record a diagnosis to issue prescriptions48) administer the large majority of antibiotic prescribing for infants. This feature of the health care system limited our ability to explore infection trends coincident with antibiotic prescribing changes over time or across population subgroups. This limitation is exemplified by the differences between our observations of antibiotic dispensing trends compared with a previous description17 of infection trends in Denmark for Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Bordetella pertussis. We also lacked individual-level data on vaccination receipt, which limited inference in the interrupted time series analysis. We note limited ability to compare results to a control population in the interrupted time series analysis33,49 because the IRF bulletin and PCV programs pertained to all children born in Denmark. In addition, our ability to observe stronger effects of the bulletin and PCV programs on antibiotic dispensing may have been limited by ongoing stewardship efforts and lower antibiotic utilization in Denmark compared with most other European countries during the study period.8,23 Antibiotic prescribing trends over time are driven by the prevalence and infectiousness of circulating illnesses; although we controlled for seasonality and carefully selected relevant interruptions and their onset times, our results are limited by our inability to account for underlying differences in circulating illness from year to year and other unmeasured or unknown temporal influences.

This study also has several strengths. The registry databases facilitated our implementation of a large, well-defined, nationwide, population-based cohort study of all children born in Denmark during this 9-year period when antibiotic prescribing practices were in transition. The tax-supported health care system for the entire Danish population includes free access to medical care and partial reimbursement of prescribed medications,29 leading to minimal disparity in access to health care services in this study. In our study, we linked individual-level data across multiple registries to compare infants’ redeemed antibiotic prescriptions with demographic and health-related characteristics. Furthermore, the registries that we used for this study contain accurate data on the date and medication type of redeemed antibiotic prescriptions, date of birth, residence, and other variables we assessed.28–30

Our estimates for the total birth season cohort effect on antibiotic prescribing are unlikely to be confounded because season of birth is not affected by other risk factors for antibiotic use during infancy (eg, birth order, sex, gestational age at birth).50 Throughout the study period, population-level characteristics of children born in Denmark did not change, no new antibiotic formulations were introduced, and the government’s administrative system for prescribing and dispensing antibiotics to infants did not change. Stability of the study population and data systems during the study period limits potential for the interrupted time series study to be biased by confounding, measurement error, or cointervention effects.32,49

Conclusions

Children’s season of birth impacted both their overall risk of having a redeemed antibiotic prescription during infancy and their age at first redeemed antibiotic prescription. Antibiotic prescribing was dynamic over the study period but decreased after a bulletin with guidelines on rational antibiotic use in general practice and rollout of 2 nationwide PCV programs. The approaches used in this study provide a working example of how “big data” can enable researchers to extract new information on risk, rate, and burden measures of antibiotic prescribing in infants, including the correlation between these measures. Finally, these birth cohort effects have implications for future studies of antibiotic stewardship, effectiveness, and safety in children, because some children may be inherently more susceptible than others to downstream effects of antibiotics.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- IRF

Institute for Rational Pharmacotherapy

- MBR

Danish Medical Birth Registry

- PCV

pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- PCV7

7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- PCV13

13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

Footnotes

Dr Kinlaw conceptualized and designed the study, conducted data analysis, interpreted data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Stürmer conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Lund, Kappelman, Daniels, Mack, and Sørensen conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Pedersen and Ms Frøslev contributed to data analysis, interpreted data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Kinlaw reports receiving grant support for this study from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32 HD052468-05); a National Service Research Award Postdoctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (5T32 HS000032-28); the Graduate School, Department of Epidemiology, and Gillings School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology, which receives financial support from GlaxoSmithKline, UCB BioSciences, and Merck. Dr Stürmer reports receiving salary support as director of the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology (current members: GlaxoSmithKline, UCB BioSciences, and Merck) and research support from pharmaceutical companies (Amgen, AstraZeneca) to the Department of Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Dr Stürmer does not accept personal compensation of any kind from any pharmaceutical company. Dr Stürmer owns stock in Novartis, Roche, BASF, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Novo Nordisk. Dr Lund reports receiving grant support from a Research Starter Award from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America Foundation to the University of North Carolina Department of Epidemiology. Dr Pedersen, Ms Frøslev, and Dr Sørensen did not report receiving fees, honoraria, grants, or consultancies; the Department of Clinical Epidemiology is, however, involved in studies with funding from various companies as research grants to (and administered by) Aarhus University. Dr Kappelman reports receiving grant support and consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson & Johnson and stock ownership in GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson & Johnson. Dr Mack reports being a full-time employee at Quintiles, Inc, and as such consults for large pharmaceutical companies. Dr Daniels has indicated she has no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32 HD052468-05); a National Service Research Award Postdoctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (5T32 HS000032-28); the Graduate School, Department of Epidemiology, and Gillings School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology, which receives financial support from GlaxoSmithKline, UCB BioSciences, and Merck. The funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of the study, data analysis or interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Kinlaw reports receiving grant support for this study from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32 HD052468-05); a National Service Research Award Postdoctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (5T32 HS000032-28); the Graduate School, Department of Epidemiology, and Gillings School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology, which receives financial support from GlaxoSmithKline, UCB BioSciences, and Merck. Outside this study, Dr Stürmer reports receiving investigator-initiated research funding and support as principal investigator (R01 AG023178) from the National Institute on Aging and as coinvestigator (R01 CA174453, R01 HL118255, R21-HD080214), National Institutes of Health (NIH); Dr Stürmer also receives salary support as director of the Comparative Effectiveness Research Strategic Initiative, the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute, the University of North Carolina Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1TR001111), and as director of the Center for Pharmacoepidemiology (current members: GlaxoSmithKline, UCB BioSciences, Merck) and research support from pharmaceutical companies (Amgen and AstraZeneca) to the Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Dr Stürmer does not accept personal compensation of any kind from any pharmaceutical company; Dr Stürmer owns stock in Novartis, Roche, BASF, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Novo Nordisk. Outside this study, Dr Lund reports receiving grant support from the University of North Carolina Oncology Clinical Translational Research Training Program (K12 CA120780), and from a Research Starter Award from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America Foundation to the University of North Carolina Department of Epidemiology. Outside this study, Dr Pedersen, Ms Frøslev, and Dr Sørensen did not report receiving fees, honoraria, grants or consultancies; the Department of Clinical Epidemiology is, however, involved in studies with funding from various companies as research grants to (and administered by) Aarhus University. Outside this study, Dr Kappelman reports receiving grant support and consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson & Johnson, and stock ownership in GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson & Johnson. Outside this study, Dr Mack reports being a full-time employee at Quintiles, Inc, and as such consults for large pharmaceutical companies; and Dr Daniels has indicated she has no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2017-1695.

References

- 1.Nyquist A-C, Gonzales R, Steiner JF, Sande MA. Antibiotic prescribing for children with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis. JAMA. 1998;279(11):875–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, Sande MA. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanovska V, Hek K, Mantel Teeuwisse AK, Leufkens HGM, Nielen MMJ, van Dijk L. Antibiotic prescribing for children in primary care and adherence to treatment guidelines. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(6):1707–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keith T, Saxena S, Murray J, Sharland M. Risk-benefit analysis of restricting antimicrobial prescribing in children: what do we really know? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23(3):242–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson LL, Woods CW, Ginsburg GS. A novel diagnostic approach may reduce inappropriate antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12(3):279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marra F, Marra CA, Richardson K, Lynd LD, Fitzgerald MJ. Antibiotic consumption in children prior to diagnosis of asthma. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11(32):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dommergues MA, Hentgen V. Decreased paediatric antibiotic consumption in France between 2000 and 2010. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44(7):495–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lusini G, Lapi F, Sara B, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in paediatric populations: a comparison between Viareggio, Italy and Funen, Denmark. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19(4):434–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaz LE, Kleinman KP, Raebel MA, et al. Recent trends in outpatient antibiotic use in children. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):375–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCaig LF, Besser RE, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial prescribing rates for children and adolescents. JAMA. 2002;287(23):3096–3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnus MC, Vestrheim DF, Nystad W, et al. Decline in early childhood respiratory tract infections in the Norwegian mother and child cohort study after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(9):951–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappas DE, Owen Hendley J. Otitis media. A scholarly review of the evidence. Minerva Pediatr. 2003;55(5):407–414 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1451–1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson PL, Spyridis N, Sharland M, et al. Changes in clinical indications for community antibiotic prescribing for children in the UK from 1996 to 2006: will the new NICE prescribing guidance on upper respiratory tract infections just be ignored? Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(5):337–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tregoning JS, Schwarze J. Respiratory viral infections in infants: causes, clinical symptoms, virology, and immunology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):74–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):346]. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/131/3/e964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pottegård A, Broe A, Aabenhus R, Bjerrum L, Hallas J, Damkier P. Use of antibiotics in children: a Danish nationwide drug utilization study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(2):e16–e22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Högberg L, Oke T, Geli P, Lundborg CS, Cars O, Ekdahl K. Reduction in outpatient antibiotic sales for pre-school children: interrupted time series analysis of weekly antibiotic sales data in Sweden 1992-2002. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(1):208–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holstiege J, Schink T, Molokhia M, et al. Systemic antibiotic prescribing to paediatric outpatients in 5 European countries: a population-based cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:174–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stam J, van Stuijvenberg M, Grüber C, et al. ; Multicenter Infection Prevention Study 1 (MIPS 1) Study Group . Antibiotic use in infants in the first year of life in five European countries. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(9):929–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider-Lindner V, Quach C, Hanley JA, Suissa S. Secular trends of antibacterial prescribing in UK paediatric primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(2):424–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson JR, Wang L, Klima J, et al. Healthcare claims data: an underutilized tool for pediatric outpatient antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(11):1479–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M; ESAC Project Group . Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):579–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedersen ASS, Gahrn-Hansen B. Rationel Farmakoterapi Nr. 4 (April 2007); Antibiotikavejledning Til Almen Praksis. Available at: www.irf.dk/dk/publikationer/rationel_farmakoterapi/maanedsblad/2007/maanedsblad_nr_4_april_2007.htm. Accessed January 1, 2011

- 25.Andersen PH. Pneumococcal vaccine in childhood vaccination programme. EPI-NEWS. 2007. Available at: www.ssi.dk/∼/media/Indhold/EN - engelsk/EPI-NEWS/2007/PDF/EPI-NEWS - 2007 - No 37ab.ashx. Accessed August 9, 2014

- 26.Valentiner-Branth P, Andersen P, Simonsen J, et al. PCV 7 coverage & invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) 2008/2009. EPI-NEWS. Available at: www.ssi.dk/English/News/EPI-NEWS/2010/No 7-8 - 2010.aspx. Accessed August 9, 2014

- 27.Ingels H, Rasmussen J, Andersen PH, et al. ; Danish Pneumococcal Surveillance Collaboration Group 2009-2010 . Impact of pneumococcal vaccination in Denmark during the first 3 years after PCV introduction in the childhood immunization programme. Vaccine. 2012;30(26):3944–3950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan W, Fonager K, Olsen J, Sørensen HT. Prenatal factors and use of anti-asthma medications in early childhood: a population-based Danish birth cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18(8):763–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johannesdottir SA, Horváth-Puhó E, Ehrenstein V, Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: the Danish National Database of Reimbursed Prescriptions. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:303–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gillings D, Makuc D, Siegel E. Analysis of interrupted time series mortality trends: an example to evaluate regionalized perinatal care. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(1):38–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, Avorn JL, et al. The impact of reducing cardiovascular medication copayments on health spending and resource utilization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(18):1817–1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolwijk AM, Straatman H, Zielhuis GA. Studying seasonality by using sine and cosine functions in regression analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(4):235–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brookhart MA, Rothman KJ. Simple estimators of the intensity of seasonal occurrence. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(67):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nam J. Efficient method for identification of cyclic trends in incidence. Commun Stat Theory Methods. 1983;12(9):1053–1068 [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Danish Health Data Authority Danish register of medicinal product statistics, Statens Serum Institut. Medstat.dk. Available at: www.medstat.dk/en. Accessed June 26, 2016

- 39.Mai X-M, Kull I, Wickman M, Bergström A. Antibiotic use in early life and development of allergic diseases: respiratory infection as the explanation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(8):1230–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraemer HC. Events per person-time (incidence rate): a misleading statistic? Stat Med. 2009;28(6):1028–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole SR, Hudgens MG, Brookhart MA, Westreich D. Risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(4):246–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richardson DB, Cole SR, Langholz B. Regression models for the effects of exposure rate and cumulative exposure. Epidemiology. 2012;23(6):892–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kozyrskyj AL, Bahreinian S, Azad MB. Early life exposures: impact on asthma and allergic disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(5):400–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Statens Serum Institut Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV] 1 [3 months] vaccination completion (Konjugeret pneumokok-vaccine [PCV] 1 [3 måneder] vaccinationstilslutning). Infectious diseases (Smitteberedskab). Available at: www.ssi.dk/Smitteberedskab/Sygdomsovervaagning/VaccinationSurveillance.aspx?vaccination=8&xaxis=Cohort&sex=3&landsdel=100&show=Graph&datatype=Vaccination&extendedfilters=False#HeaderText. Accessed March 22, 2017

- 45.Statens Serum Institut Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV] 2 [5 months] vaccination completion (Konjugeret pneumokok-vaccine [PCV] 2 [5 måneder] vaccinationstilslutning). Infectious diseases (Smitteberedskab). Available at: www.ssi.dk/Smitteberedskab/Sygdomsovervaagning/VaccinationSurveillance.aspx?vaccination=9&sex=3&landsdel=100&xaxis=Cohort&show=Graph&datatype=Vaccination&extendedfilters=False#HeaderText. Accessed March 22, 2017

- 46.Statens Serum Institut Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV] 3 [12 months] vaccination completion (Konjugeret pneumokok-vaccine [PCV] 3 [12 måneder] vaccinationstilslutning). Infectious diseases (Smitteberedskab). Available at: www.ssi.dk/Smitteberedskab/Sygdomsovervaagning/VaccinationSurveillance.aspx?xaxis=Cohort&vaccination=10&sex=3&landsdel=100&show=&datatype=Vaccination&extendedfilters=False#HeaderText. Accessed March 22, 2017

- 47.Harboe ZB, Dalby T, Weinberger DM, et al. Impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in invasive pneumococcal disease incidence and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(8):1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moth G, Vedsted P, Schiøtz P. Identification of asthmatic children using prescription data and diagnosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jandoc R, Burden AM, Mamdani M, Lévesque LE, Cadarette SM. Interrupted time series analysis in drug utilization research is increasing: systematic review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(8):950–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Validity in epidemiologic studies In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:128–147 [Google Scholar]