Abstract

Purpose/introduction

The present study investigates potential associations between liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) measured sex hormones, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and bone ultrasound parameters at the heel in men and women from the general population.

Methods

Data from 502 women and 425 men from the population-based Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP-TREND) were used. Cross-sectional associations of sex hormones including testosterone (TT), calculated free testosterone (FT), dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS), androstenedione (ASD), estrone (E1) and SHBG with quantitative ultrasound (QUS) parameters at the heel, including broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA), speed of sound (SOS) and stiffness index (SI) were examined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multivariable quantile regression models.

Results

Multivariable regression analysis showed a sex-specific inverse association of DHEAS with SI in men (Beta per SI unit = − 3.08, standard error (SE) = 0.88), but not in women (Beta = − 0.01, SE = 2.09). Furthermore, FT was positively associated with BUA in men (Beta per BUA unit = 29.0, SE = 10.1). None of the other sex hormones (ASD, E1) or SHBG was associated with QUS parameters after multivariable adjustment.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional population-based study revealed independent associations of DHEAS and FT with QUS parameters in men, suggesting a potential influence on male bone metabolism. The predictive role of DHEAS and FT as a marker for osteoporosis in men warrants further investigation in clinical trials and large-scale observational studies.

Abbreviations: LC-MS, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; TT, testosterone; FT, free testosterone; ASD, androstenedione; E1, estrone; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; QUS, quantitative ultrasound; BUA, broadband ultrasound attenuation; SOS, speed of sound; SI, stiffness index; BMD, bone mineral density; SHIP, Study of Health in Pomerania; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval

Keywords: Bone, Sex hormones, Stiffness index, DHEAS

Highlights

-

•

Population-based data of healthy men and women from the general population

-

•

Sex hormone panel measured by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

-

•

Associations of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate and free testosterone with bone ultrasound parameters in men

-

•

Estrone, androstenedione and SHBG were not associated with bone ultrasound parameters in both sexes.

1. Introduction

Previous research suggested a potential link between sex hormones and bone metabolism (Venken et al., 2008). Exemplarily, estrogen and dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS) exposure in adolescence have been related to skeletal maturation and bone mineral density, same as estrogen deficiency and decreasing sex hormone concentrations to bone loss (Dhuper et al., 1990, Porcu et al., 1994, Gonnelli et al., 2011). Beside well-established risk factors for osteoporosis, including aging, female sex, pre-existing fractures and physical inactivity, previous experimental research suggests a bi-directional link between sex hormones and bone metabolism (Oury et al., 2011). Sex hormones and sex hormone-binding globulin has been shown to be correlated with loss of bone mineral density (BMD) (Hsu et al., 2015, Park et al., 2017), but not in all studies (Paller et al., 2009, Kuchuk et al., 2007, Araujo et al., 2008, Gennari et al., 2003). Previous studies revealed association between sex hormones and fracture risk (Ohlsson et al., 2017, Cauley et al., 2017, Shahinian et al., 2005), particularly for estradiol (Mellstrom et al., 2008, Amin et al., 2006, Garnero et al., 2000, Laurent et al., 2015, Cauley et al., 2010, Khosla et al., 2008, LeBlanc et al., 2009). Furthermore, previous research in men related testosterone (TT) and DHEAS to markers of bone turnover (Kyvernitakis et al., 2013). However, these observational findings are only of limited clinical utility (Bjornerem et al., 2007, Orwoll et al., 2017).

In summary, previous studies revealed inconsistent associations and some are limited in their generalizability due to selected, small or sex-specific samples and immunoassay-based sex hormone measurements. The present study investigates a comprehensive panel of sex hormones measured by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and their association with bone ultrasound parameters in men and women from the general population.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

We used data from the population-based Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP-TREND). Details regarding design, recruitment and procedure have been previously published (Volzke, 2012, John et al., 2001, Volzke et al., 2011). In brief, a representative sample with men and women 20 to 79 years of age was randomly selected from the population registries in Northeast Germany in September 2008, including the cities Greifswald, Stralsund, Anklam and 29 surrounding communities and stratified into 24 age- and sex-specific strata. Of initially 8016 addressed and randomly selected inhabitants of West Pomerania a total of 4420 subjects participated until September 2012 in the baseline examination of SHIP-TREND. The study follows the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Greifswald.

The subsample with sex hormone data availability was limited to the first 1000 SHIP-TREND participants that fasted for at least 10 h prior to blood sampling. Of these, 63 participants were excluded due to the presence of at least one of the following conditions: missing quantitative ultrasound (QUS) measurement, intake of vitamin D supplements, parathyroid hormones and analogues, bone metabolism influencing medication [bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, glucocorticoids, corticosteroids], testosterone-5-alpha reductase inhibitors, hormone antagonists and related agents, men taking sexual hormones, pregnant women and participants with missing confounder or hormone data, resulting in a study population of 927 individuals (425 men, 502 women).

2.2. Measurements

Information on age, sex, socio-demographics, medical history, and health behavior were collected by computer-aided personal interviews. Smoking habits were categorized into “never”, “current” and “former” smoker. Participants were classified as being physically inactive, if they did not engage in physical training for at least 1 h a week. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using an inelastic tape, midway between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest in the horizontal plane. After a resting period of at least 5 min, systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured three times (interval: 3 min) on the right arm of seated subjects by use of an oscillometric digital blood pressure monitor (HEM-705CP, Omron Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). For the present analysis, the mean of the second and third measurements were used. Blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg or use of antihypertensive medication was defined as hypertension (Mancia et al., 2007).

2.3. Laboratory measures

Blood samples were taken from the cubital vein in the supine position between 8:00 AM to 7:00 PM and prepared for storage at − 80 °C for further analysis. Serum concentrations of TT, androstenedione (ASD) and estrone (E1) were measured by a validated routine method from frozen aliquots using LC-MS/MS in the Department of Clinical Chemistry at the University Hospital of South Manchester (Manchester, UK) with the result that the standard curve was linear to 50.0 nmol/l, the lower limit of quantitation was 0.25 nmol/l, and intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were < 10% for TT and ASD over the range 0.3–35 nmol/l (Thienpont et al., 2008). For E1, the inter-assay imprecision was 5.3, 3.8 and 5.1% at concentrations of 125, 400 and 1500 pmol/l, while the intra-assay imprecision for these concentrations were 4.0, 3.4 and 5.0%. All means were within 8% of the PBS-based quality control targets. The measurement range for E1 was 25–2000 pmol/l. The lower limit of detection for E1 was 3.9 pmol/l. The lower limit of quantitation for E1 was 6 pmol/l.

Serum DHEAS concentrations were measured by a competitive chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay on an Immulite 2500 analyzer (DPC Biermann GmbH, Bad Nauheim, Germany) with an inter-assay coefficient of variation of 14.0%, a systematic deviation of + 0.21% at the 48 μg/dl level, and 8.4% with a systematic deviation of − 5.0% at the 128 μg/dl. Serum SHBG concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay on an Advia Centaur (Siemens, Eschborn, Germany) with an inter-assay coefficient of variation of 6.6% at the 27.1 nmol/l level, 7.6% at the 48.2 nmol/l level and 7.7% at the 52.3 nmol/l level. Free testosterone (FT) was calculated: FT (nmol/l) = ((− a + √ b) / c) / 10− 9 with a = SHBG (nmol/l) − TT (nmol/l) + 23.43, b = a2 + (4 ∗ 23.43 ∗ TT (nmol/l)) and c = 2 ∗ 23.43 ∗ 109 for a standard average albumin concentration of 4.3 g/dl (Vermeulen et al., 1999).

2.4. Quantitative ultrasound measurements

QUS measurements at the heel (os calcis) were performed with the water-based bone ultrasonometer Achilles InSight (GE Medical Systems Ultrasound, GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA). Based on the measured speed of sound (SOS) in meters per second (m/s) and the frequency-dependent attenuation of the sound waves (BUA) in decibels per megahertz (dB/MHz), stiffness index (SI) was calculated according to the following formula: SI = (0.67 × BUA) + (0.28 × SOS) − 420. Two used Achilles InSight devices had in vivo precision and accuracy of < 2.0% CV. QUS measurements were performed successively on both feet of seated participants by trained and certified examiners. All examiners underwent an initial certification process and annual re-certifications. During the annual recertification, all examiners performed two QUS measurements on the right foot of five volunteers. Coefficients of variation (CV) for the intra-observer-variability (BUA 2.98%, SOS 0.39%, stiffness index 2.74%) and the inter-observer-variability (BUA 3.47%, SOS 0.36%, stiffness index 3.29%) were determined. Alcohol was used as a coupling agent. All subjects with implants, protheses or amputations in or below the knee were excluded from the measurements, as were participants with open wounds or infections below the knee. Finally, we do not report data for wheelchair-bound participants, for participants whose feet could not be placed correctly and for participants who reported injuries or surgeries during the last 12 months before the examinations.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Continuous data is expressed as median (25th; 75th quartile) and nominal data as percentage. Kruskal-Wallis (continuous data) or Chi2 test (nominal data) were used for intergroup comparisons by sex. In a first step, adjusted mean levels of SOS and BUA were separately calculated for men and women by analysis of variance (ANOVA). At this, sex hormone concentrations were categorized into three groups, according to the age- and sex-specific tertiles. In a second step, cross-sectional associations between sex hormones and QUS parameters were assessed using quantile regression modelling, a statistical method to estimate models for the conditional median function and other conditional quantile functions (Koenker, 2005). Quantile regression has the advantage of having no distributional assumption. In case of a non-linear association, tested with likelihood ratio test, restricted cubic splines with three knots were used. Three knots were pre-specified located at the 5th, 50th and 95th percentile as recommended by Stone and Koo (1985), resulting in one component of the spline function: e.g. testosterone′. Adjusted means or beta estimates and their 95% confidence interval [95% confidence interval (CI)] or standard error were calculated. To address potential selection bias, we included inverse probability weights into the multivariable analysis. All models were adjusted for age, smoking status, physical inactivity, waist circumference, hypertension, serum calcium and total cholesterol. In a third step, regression models were additionally adjusted for DHEAS. All statistical analysis were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS statistical software, version 9.3, SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary; NC, USA).

3. Results

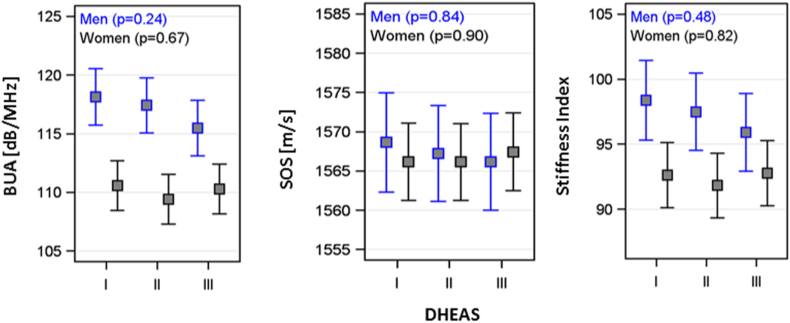

Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented stratified by sex (Table 1). Study participants had an average age of 49 years and a mean BMI of 26.8 kg/m2. ANOVA revealed an inverse trend between DHEAS and SI in men (p = 0.48), but not in women (p = 0.82) (Fig. 1). Among men, the estimated mean SI level was higher in the first [SI: 98.4 (95% confidence interval (CI) 95.9–101.4)], compared to the third DHEAS tertile [SI: 95.9 (95% CI 92.9–98.8)]. BUA and SOS showed no significant associations.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | All participants (n = 927) |

Men (n = 425) |

Women (n = 502) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 49 (40; 59) | 50 (39; 60) | 49 (40; 58) | 0.44 |

| Waist Circumference, cm | 87.3 (78.2; 97.0) | 94 (87; 102) | 81 (74; 90) | < 0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.8 (24.1; 29.9) | 27.7 (25.0; 30.2) | 26.0 (23.1; 29.4) | < 0.01 |

| Total testosterone, nmol/l | 1.47 (0.78; 16.64) | 17.3 (14.3; 20.5) | 0.81 (0.61; 1.04) | < 0.01 |

| Free testosterone, nmol/l | 0.022 (0.009; 0.0326) | 0.333 (0.281; 0.402) | 0.009 (0.007; 0.013) | < 0.01 |

| Androstenedione, nmol/l | 2.56 (1.95; 3.58) | 2.84 (2.18; 3.72) | 2.33 (1.75; 3.44) | < 0.01 |

| DHEAS, mg/l | 1.29 (0.80; 1.98) | 1.73 (1.01; 2.55) | 1.08 (0.69; 1.51) | < 0.01 |

| SHBG, nmol/l | 45 (33; 62) | 36 (29; 46) | 56 (43; 80) | < 0.01 |

| Estrone, nmol/la | 116 (84; 171) | 115 (95; 148) | 117 (73; 222) | 0.82 |

| SOS, m/s | 1566 (1544; 1586) | 1567 (1543; 1588) | 1565 (1546; 1585) | 0.71 |

| BUA, dB/MHz | 112 (104; 123) | 117 (108; 126) | 108 (101; 119) | < 0.01 |

| Stiffness index | 93 (83; 106) | 97 (85; 109) | 92 (81; 103) | < 0.01 |

| Physically inactive, % | 26.6 | 26.8 | 26.5 | 0.91 |

| Smoking, % | < 0.01 | |||

| Never smoker | 41.8 | 31.8 | 50.2 | |

| Former smoker | 35.6 | 45.2 | 27.5 | |

| Current smoker | 22.7 | 23.1 | 22.3 | |

| Hormone replacement, % | 11.8 | – | 21.7 | – |

Continuous data are expressed as median (25th and 75th percentiles); nominal data are given as percentages. χ2-Test (nominal data) or Kruskal-Wallis test (interval data) were used for intergroup comparisons by sex.

SHBG = sex hormone-binding globulin; DHEAS = dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate; SOS = speed of sound; BUA = frequency-dependent attenuation of the sound waves.

Subgroup of 374 men, 488 women.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound-based bone parameters by tertiles of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate.

Estimated mean levels of frequency-dependent attenuation of the sound waves (BUA), speed of sound (SOS) and stiffness index, with 95% confidence interval by tertiles of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS) in men and women. Analysis of variance was adjusted for age, smoking status, physical inactivity, waist circumference, hypertension, serum calcium and total cholesterol.

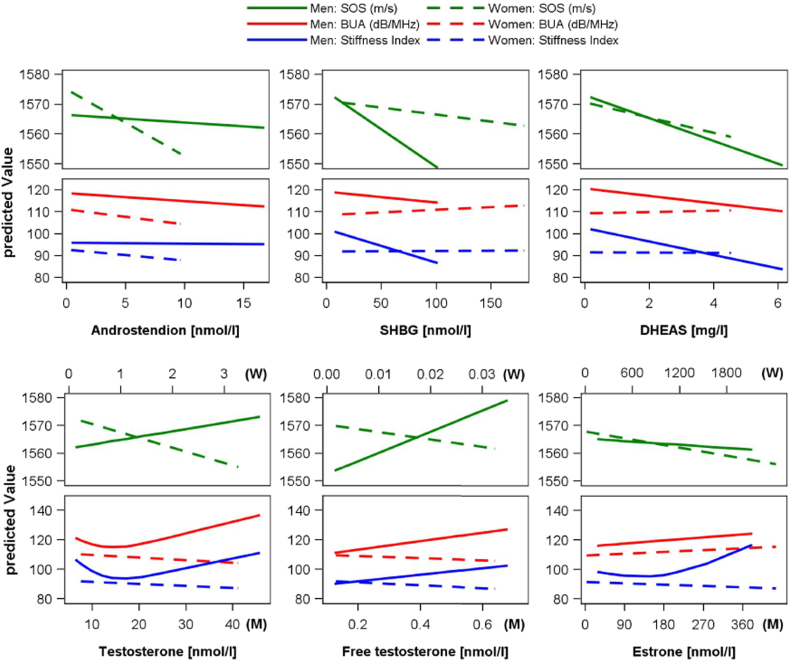

Table 2 presents multivariable-adjusted associations between sex hormones and QUS parameters. Among men, multivariable regression models (Fig. 2) showed a consistent inverse association of DHEAS across all QUS parameters including BUA [Beta = − 1.72, standard error (SE) = 0.72, p = 0.02], SOS (Beta = − 3.83, SE = 1.6, p = 0.02) and SI (Beta = − 3.08, SE = 0.88, p < 0.01). Furthermore, FT showed a significant positive association with BUA after multivariable adjustment (Beta = 29.0, SE = 10.1, p < 0.01). Additional adjustment for DHEAS, revealed an inverse association of FT with SI (Supplement Table 3). Analysis of other sex hormones among men, including assessment of non-linear associations of TT and E1 by cubic splines, revealed no further associations with QUS parameters. Among women, none of the analyzed sex hormones were associated with QUS parameters. The performed sensitivity analysis did not change the results substantially.

Table 2.

Multivariable adjusted associations between sex hormones and QUS parameters, stratified by sex.

| BUA |

SOS |

Stiffness index |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | |

| Men | |||||||||

| Androstenedione | − 0.36 | 1.27 | 0.78 | − 0.26 | 1.39 | 0.85 | − 0.04 | 1.32 | 0.98 |

| DHEAS | − 1.72 | 0.72 | 0.02 | − 3.83 | 1.60 | 0.02 | − 3.08 | 0.88 | < 0.01 |

| Estrone | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.38 | − 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.85 | − 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.58 |

| Estrone′ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.46 | ||||||

| SHBG | − 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.58 | − 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.11 | − 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

| Testosterone | − 3.60 | 2.13 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.48 | − 5.46 | 2.63 | 0.04 |

| Testosterone′ | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |||

| Free Testosterone | 29.0 | 10.1 | < 0.01 | 45.7 | 22.3 | 0.04 | 22.4 | 13.8 | 0.11 |

| Women | |||||||||

| Androstenedione | − 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.27 | − 2.24 | 1.27 | 0.08 | − 0.50 | 0.93 | 0.59 |

| DHEAS | 0.28 | 1.12 | 0.80 | − 2.55 | 3.40 | 0.45 | − 0.01 | 2.09 | 1.00 |

| Estrone | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.77 |

| SHBG | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.23 | − 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.94 |

| Testosterone | − 2.01 | 1.94 | 0.30 | − 5.50 | 4.01 | 0.17 | − 1.51 | 3.15 | 0.63 |

| Free Testosterone | − 118 | 142 | 0.41 | 207 | 291 | 0.35 | − 163 | 191 | 0.39 |

Estrone′ and testosterone′ are cubic spline components used for assessment of non-linear associations.

Quantile regression models were adjusted for age, smoking status, physical inactivity, waist circumference, hypertension, serum calcium, total cholesterol. Inverse probability weights were used.

SHBG = sex hormone-binding globulin; DHEAS = dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate; SOS = speed of sound; BUA = frequency-dependent attenuation of the sound waves; SE = standard error.

Fig. 2.

Quantile regression model of ultrasound-based bone parameters by sex hormones.

Predicted median levels of speed of sound (SOS), frequency-dependent attenuation of the sound waves (BUA) and stiffness index illustrated as ordinate (predicted values) by androstenedione, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS), testosterone, free testosterone and estrone levels in the men (M) and women (W). Quantile regression models were adjusted for age, smoking status, physical inactivity, waist circumference, hypertension, calcium and total cholesterol. Non-linear associations were assessed using restricted cubic splines.

4. Discussion

The present population-based study investigated cross-sectional associations of sex hormones with QUS parameters in healthy men and women from the general population. We observed a sex-specific inverse association of DHEAS with SI among men, but not among women. Furthermore, we observed a positive association between FT and BUA. After additional adjustment for DHEAS we observed a significant inverse association of FT with SI. Previous observational studies in different settings and with different assessments have shown similar associations of DHEAS and TT with bone metabolism (Kyvernitakis et al., 2013, Mellstrom et al., 2006).

DHEAS occurs in the zona reticularis of the adrenal cortex, under regulatory control of adrenocorticotropic hormone by the pituitary gland. As sulphated inactive storage form of the most abundant steroid hormone precursor dehydroepiandrosterone in humans, DHEAS is converted to more active sex hormones on the level of targeted cells. Extragonadal tissue and commons for gonadal synthesis have the same enzymatic pathway to convert steroid precursors like DHEAS, as well as TT, to more active sex hormones (Labrie et al., 2000). Although a directly acting DHEA receptor has not yet been identified in bone cells, DHEAS is considered as the main source of estrogen in post-menopausal women, while the estrogen production in men is more dependent on the peripheral aromatisation of testosterone (Simpson, 2000). Thus, estrogen (Rochira et al., 2007), as well as the inhibition of osteoblasts apoptosis (Wang et al., 2007) and other substances, like growth factors (Bodine et al., 1995) and interleukins (Bellido et al., 1995), were discussed as potential mediators of the association between DHEAS and bone metabolism. Additionally, a protective role of DHEAS in bone metabolism might be explained through the inhibition of osteoclasts at the mRNA level (Wang et al., 2006).

However, these points and recent studies (Park et al., 2017, Ohlsson et al., 2017, Kyvernitakis et al., 2013, Mellstrom et al., 2006) suggest a positive directed association between DHEAS and bone metabolism. Proceeding from previous studies, we expected additional associations between the investigated sex hormones and QUS parameters. But, except DHEAS and FT, none of the alternatively measured sex hormones were associated with bone ultrasound parameters. In contrast to our results, previous studies among post-menopausal women reported positive association of DHEAS with SI (Hosoda et al., 2008) and an association of estradiol with QUS (Gonnelli et al., 2011).

These inconsistencies should be interpreted in light of variable statistical and analytical methods among previously published studies, including 1) study samples selected by menopausal status or sex, 2) the population-based nature of our study sample, comprising comparably healthy individuals from the general population, and 3) potential measurement bias from different sex hormone assessments. However, there is no conclusive explanation for the contrasting associations in men. Thus, further research is needed to elucidate associations of sex hormones with QUS parameters, especially regarding DHEAS.

Strengths of the present study include firstly, the LC-MS-based sex hormone measurements, which have been shown to be superior to conventional immunoassay-based measurements (Moal et al., 2007), secondly, the coherent assessment of relevant confounders for multivariable regression analysis, as well as thirdly, a high prevalence of behavioral risk factors in a population-based sample of men and women from the general population (Volzke et al., 2015).

Limitations may arise from potential selection bias due to data availability, which is restricted to a subsample of the full SHIP-TREND cohort. We addressed this potential source of bias, by inverse probability weighting, but without any relevant impact on the revealed results. Further limitations include lacking data on estradiol concentrations, bone turnover markers, vitamin D status, menstrual cycle rhythm and self-reported prevalence of polycystic ovarian syndrome among women. Finally, the population-based research setting did not allow dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, the clinical gold standard for osteoporosis diagnoses. However, the QUS measurements performed in the present study do not only offer the advantages of being simpler, less expensive, portable and free of ionizing radiation, but were previously validated in their clinical utility to assess bone health (Mohr et al., 2004).

5. Conclusion

The present population-based study observed sex-specific associations of DHEAS and FT with QUS parameters in men, but not in women. None of the other sex hormones or SHBG was associated with QUS parameters at the heel. The potential influence of FT, and particularly the sex hormone precursor DHEAS, on bone ultrasound parameters, and its predictive role as osteoporosis marker warrants further investigation in clinical trials and observational studies.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Multivariable regression models of the associations between sex hormones and QUS parameters, additionally adjusted for DHEAS.

Funding

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant no. 01ZZ9603), the Ministry of Cultural Affairs (grant no. 01ZZ0103), the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania (grant no. 01ZZ0403) and German Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

Konrad Pätzug, Nele Friedrich, Hanna Kische, Anke Hannemann, Henry Völzke, Matthias Nauck, Brian G. Keevil and Robin Haring declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Amin S., Zhang Y., Felson D.T., Sawin C.T., Hannan M.T., Wilson P.W., Kiel D.P. Estradiol, testosterone, and the risk for hip fractures in elderly men from the Framingham Study. Am. J. Med. 2006;119:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo A.B., Travison T.G., Leder B.Z., McKinlay J.B. Correlations between serum testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone-binding globulin and bone mineral density in a diverse sample of men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;93:2135–2141. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellido T., Jilka R.L., Boyce B.F., Girasole G., Broxmeyer H., Dalrymple S.A., Murray R., Manolagas S.C. Regulation of interleukin-6, osteoclastogenesis, and bone mass by androgens. The role of the androgen receptor. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95:2886–2895. doi: 10.1172/JCI117995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornerem A., Ahmed L.A., Joakimsen R.M., Berntsen G.K., Fonnebo V., Jorgensen L., Oian P., Seeman E., Straume B. A prospective study of sex steroids, sex hormone-binding globulin, and non-vertebral fractures in women and men: the Tromso Study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2007;157:119–125. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine P.V., Riggs B.L., Spelsberg T.C. Regulation of c-fos expression and TGF-beta production by gonadal and adrenal androgens in normal human osteoblastic cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995;52:149–158. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)00165-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauley J.A., Ewing S.K., Taylor B.C., Fink H.A., Ensrud K.E., Bauer D.C., Barrett-Connor E., Marshall L., Orwoll E.S. Sex steroid hormones in older men: longitudinal associations with 4.5-year change in hip bone mineral density–the osteoporotic fractures in men study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95:4314–4323. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauley J.A., Danielson M.E., Jammy G.R., Bauer D.C., Jackson R., Wactawski-Wende J., Chlebowski R.T., Ensrud K.E., Boudreau R. Sex steroid hormones and fracture in a multiethnic cohort of women: the Women's Health Initiative Study (WHI) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;102:1538–1547. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhuper S., Warren M.P., Brooks-Gunn J., Fox R. Effects of hormonal status on bone density in adolescent girls. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1990;71:1083–1088. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-5-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnero P., Sornay-Rendu E., Claustrat B., Delmas P.D. Biochemical markers of bone turnover, endogenous hormones and the risk of fractures in postmenopausal women: the OFELY study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2000;15:1526–1536. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.8.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennari L., Merlotti D., Martini G., Gonnelli S., Franci B., Campagna S., Lucani B., Dal Canto N., Valenti R., Gennari C., Nuti R. Longitudinal association between sex hormone levels, bone loss, and bone turnover in elderly men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:5327–5333. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonnelli S., Caffarelli C., Tanzilli L., Merlotti D., Gennari L., Rossi S., Lucani B., Campagna M.S., Franci B., Nuti R. The association of body composition and sex hormones with quantitative ultrasound parameters at the calcaneus and phalanxes in elderly women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2011;89:456–463. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda H., Fukui M., Nakayama I., Asano M., Kadono M., Hasegawa G., Yoshikawa T., Nakamura N. Bone mass and bone resorption in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2008;57:940–945. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu B., Cumming R.G., Seibel M.J., Naganathan V., Blyth F.M., Bleicher K., Dave A., Le Couteur D.G., Waite L.M., Handelsman D.J. Reproductive hormones and longitudinal change in bone mineral density and incident fracture risk in older men: the concord health and aging in men project. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015;30:1701–1708. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John U., Greiner B., Hensel E., Ludemann J., Piek M., Sauer S., Adam C., Born G., Alte D., Greiser E., Haertel U., Hense H.W., Haerting J., Willich S., Kessler C. Study of Health In Pomerania (SHIP): a health examination survey in an east German region: objectives and design. Soz. Praventivmed. 2001;46:186–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01324255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosla S., Amin S., Orwoll E. Osteoporosis in men. Endocr. Rev. 2008;29:441–464. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenker R. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2005. Quantile Regression. Econometric Society Monograph Series. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchuk N.O., van Schoor N.M., Pluijm S.M., Smit J.H., de Ronde W., Lips P. The association of sex hormone levels with quantitative ultrasound, bone mineral density, bone turnover and osteoporotic fractures in older men and women. Clin. Endocrinol. 2007;67:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyvernitakis I., Saeger U., Ziller V., Bauer T., Seker-Pektas B., Hadji P. The effect of age, sex hormones, and bone turnover markers on calcaneal quantitative ultrasonometry in healthy German men. J. Clin. Densitom. 2013;16:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F., Luu-The V., Lin S.X., Simard J., Labrie C., El-Alfy M., Pelletier G., Belanger A. Intracrinology: role of the family of 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases in human physiology and disease. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;25:1–16. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent M.R., Gielen E., Vanderschueren D. Estrogens, the be-all and end-all of male hypogonadal bone loss? Osteoporos. Int. 2015;26:29–33. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2865-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc E.S., Nielson C.M., Marshall L.M., Lapidus J.A., Barrett-Connor E., Ensrud K.E., Hoffman A.R., Laughlin G., Ohlsson C., Orwoll E.S. The effects of serum testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone binding globulin levels on fracture risk in older men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:3337–3346. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G., De Backer G., Dominiczak A., Cifkova R., Fagard R., Germano G., Grassi G., Heagerty A.M., Kjeldsen S.E., Laurent S., Narkiewicz K., Ruilope L., Rynkiewicz A., Schmieder R.E., Struijker Boudier H.A., Zanchetti A., Vahanian A., Camm J., De Caterina R., Dean V., Dickstein K., Filippatos G., Funck-Brentano C., Hellemans I., Kristensen S.D., McGregor K., Sechtem U., Silber S., Tendera M., Widimsky P., Zamorano J.L., Kjeldsen S.E., Erdine S., Narkiewicz K., Kiowski W., Agabiti-Rosei E., Ambrosioni E., Cifkova R., Dominiczak A., Fagard R., Heagerty A.M., Laurent S., Lindholm L.H., Mancia G., Manolis A., Nilsson P.M., Redon J., Schmieder R.E., Struijker-Boudier H.A., Viigimaa M., Filippatos G., Adamopoulos S., Agabiti-Rosei E., Ambrosioni E., Bertomeu V., Clement D., Erdine S., Farsang C., Gaita D., Kiowski W., Lip G., Mallion J.M., Manolis A.J., Nilsson P.M., O'Brien E., Ponikowski P., Redon J., Ruschitzka F., Tamargo J., van Zwieten P., Viigimaa M., Waeber B., Williams B., Zamorano J.L., The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of H, The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of C 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur. Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellstrom D., Johnell O., Ljunggren O., Eriksson A.L., Lorentzon M., Mallmin H., Holmberg A., Redlund-Johnell I., Orwoll E., Ohlsson C. Free testosterone is an independent predictor of BMD and prevalent fractures in elderly men: MrOS Sweden. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:529–535. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellstrom D., Vandenput L., Mallmin H., Holmberg A.H., Lorentzon M., Oden A., Johansson H., Orwoll E.S., Labrie F., Karlsson M.K., Ljunggren O., Ohlsson C. Older men with low serum estradiol and high serum SHBG have an increased risk of fractures. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008;23:1552–1560. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moal V., Mathieu E., Reynier P., Malthiery Y., Gallois Y. Low serum testosterone assayed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Comparison with five immunoassay techniques. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2007;386:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr A., Barkmann R., Mohr C., Romer F.W., Schmidt C., Heller M., Gluer C.C. Quantitative ultrasound for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Röfo. 2004;176:610–617. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson C., Nethander M., Kindmark A., Ljunggren O., Lorentzon M., Rosengren B.E., Karlsson M.K., Mellstrom D., Vandenput L. Low serum DHEAS predicts increased fracture risk in older men: the MrOS Sweden study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwoll E.S., Lapidus J., Wang P.Y., Vandenput L., Hoffman A., Fink H.A., Laughlin G.A., Nethander M., Ljunggren O., Kindmark A., Lorentzon M., Karlsson M.K., Mellstrom D., Kwok A., Khosla S., Kwok T., Ohlsson C., Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study Research G The limited clinical utility of testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone binding globulin measurements in the prediction of fracture risk and bone loss in older men. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017;32:633–640. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oury F., Sumara G., Sumara O., Ferron M., Chang H., Smith C.E., Hermo L., Suarez S., Roth B.L., Ducy P., Karsenty G. Endocrine regulation of male fertility by the skeleton. Cell. 2011;144:796–809. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller C.J., Shiels M.S., Rohrmann S., Basaria S., Rifai N., Nelson W., Platz E.A., Dobs A. Relationship of sex steroid hormones with bone mineral density (BMD) in a nationally representative sample of men. Clin. Endocrinol. 2009;70:26–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.G., Hwang S., Kim J.S., Park K.C., Kwon Y., Kim K.C. The association between dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) and bone mineral density in Korean men and women. J. Bone Metab. 2017;24:31–36. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2017.24.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcu E., Venturoli S., Fabbri R., Paradisi R., Longhi M., Sganga E., Flamigni C. Skeletal maturation and hormonal levels after the menarche. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 1994;255:43–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02390674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochira V., Zirilli L., Madeo B., Aranda C., Caffagni G., Fabre B., Montangero V.E., Roldan E.J., Maffei L., Carani C. Skeletal effects of long-term estrogen and testosterone replacement treatment in a man with congenital aromatase deficiency: evidences of a priming effect of estrogen for sex steroids action on bone. Bone. 2007;40:1662–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahinian V.B., Kuo Y.F., Freeman J.L., Goodwin J.S. Risk of fracture after androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:154–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson E.R. Role of aromatase in sex steroid action. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;25:149–156. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0250149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone C.K., Koo C.Y. 1985. Additive Splines in Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Thienpont L.M., Van Uytfanghe K., Blincko S., Ramsay C.S., Xie H., Doss R.C., Keevil B.G., Owen L.J., Rockwood A.L., Kushnir M.M., Chun K.Y., Chandler D.W., Field H.P., Sluss P.M. State-of-the-art of serum testosterone measurement by isotope dilution-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2008;54:1290–1297. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.105841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venken K., Callewaert F., Boonen S., Vanderschueren D. Sex hormones, their receptors and bone health. Osteoporos. Int. 2008;19:1517–1525. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0609-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen A., Verdonck L., Kaufman J.M. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;84:3666–3672. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volzke H. Study of health in Pomerania (SHIP). Concept, design and selected results. Bundesgesundheitsbl. Gesundheitsforsch. Gesundheitsschutz. 2012;55:790–794. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volzke H., Alte D., Schmidt C.O., Radke D., Lorbeer R., Friedrich N., Aumann N., Lau K., Piontek M., Born G., Havemann C., Ittermann T., Schipf S., Haring R., Baumeister S.E., Wallaschofski H., Nauck M., Frick S., Arnold A., Junger M., Mayerle J., Kraft M., Lerch M.M., Dorr M., Reffelmann T., Empen K., Felix S.B., Obst A., Koch B., Glaser S., Ewert R., Fietze I., Penzel T., Doren M., Rathmann W., Haerting J., Hannemann M., Ropcke J., Schminke U., Jurgens C., Tost F., Rettig R., Kors J.A., Ungerer S., Hegenscheid K., Kuhn J.P., Kuhn J., Hosten N., Puls R., Henke J., Gloger O., Teumer A., Homuth G., Volker U., Schwahn C., Holtfreter B., Polzer I., Kohlmann T., Grabe H.J., Rosskopf D., Kroemer H.K., Kocher T., Biffar R., John U., Hoffmann W. Cohort profile: the study of health in Pomerania. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011;40:294–307. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volzke H., Ittermann T., Schmidt C.O., Baumeister S.E., Schipf S., Alte D., Biffar R., John U., Hoffmann W. Prevalence trends in lifestyle-related risk factors. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:185–192. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.D., Wang L., Li D.J., Wang W.J. Dehydroepiandrosterone inhibited the bone resorption through the upregulation of OPG/RANKL. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2006;3:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wang Y.D., Wang W.J., Zhu Y., Li D.J. Dehydroepiandrosterone improves murine osteoblast growth and bone tissue morphometry via mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway independent of either androgen receptor or estrogen receptor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;38:467–479. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multivariable regression models of the associations between sex hormones and QUS parameters, additionally adjusted for DHEAS.