Abstract

Background

18F-FDG PET has been used in sarcoidosis for diagnosis and determination of the extent of the disease. However, assessing inflammatory lesions in cardiac sarcoidosis using 18F-FDG can be challenging because it accumulates physiologically in normal myocardium. Another radiotracer, 3′-deoxy-3′-18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT), has been investigated as a promising PET tracer for evaluating tumor proliferative activity. In contrast to 18F-FDG, 18F-FLT uptake in the normal myocardium is low. The purpose of this retrospective study was to compare the uptake of 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG in the evaluation of cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic involvement in patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis.

Data for 20 patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis were examined. 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG PET/CT studies had been performed at 1 h after each radiotracer injection. The patients had fasted for at least 18 h before 18F-FDG PET/CT but were given no special dietary instructions regarding the period before 18F-FLT PET/CT. Uptake of 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG was examined visually and semiquantitatively using maximal standardized uptake value (SUVmax).

Results

Two patients had cardiac sarcoidosis, 7 had extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis, and 11 had both cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis. On visual analysis for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis, 4/20 18F-FDG scans were rated as inconclusive because the 18F-FDG pattern was diffuse, whereas no FLT scans were rated as inconclusive. The sensitivity of 18F-FDG PET/CT for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis was 85%; specificity, 100%; and accuracy, 90%. The corresponding values for 18F-FLT PET/CT were 92, 100, and 95%, respectively. Using semiquantitative analysis of cardiac sarcoidosis, the mean 18F-FDG SUVmax was significantly higher than the mean 18F-FLT SUVmax (P < 0.005). Both 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT PET/CT studies detected all 24 extra-cardiac lesions. Using semiquantitative analysis of extra-cardiac sarcoidosis, the mean 18F-FDG SUVmax was significantly higher than the mean 18F-FLT SUVmax (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

The results of this preliminary study suggest that 18F-FLT PET/CT can detect cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic involvement in patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis as well as 18F-FDG PET/CT, although uptake of 18F-FLT in lesions was significantly lower than that of 18F-FDG. However, 18F-FLT PET/CT may be easier to perform since it requires neither prolonged fasting nor a special diet prior to imaging.

Keywords: 18F-FLT, 18F-FDG, PET, Sarcoidosis

Background

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas in the involved organs [1]. Although it may involve any organ or system, it most commonly affects the lungs and thoracic lymph nodes, with the cardiovascular system being the third most frequently affected site [1, 2]. Although sarcoidosis has a generally favorable prognosis, 1–5% of patients die of it because of cardiorespiratory complications [1]. Therefore, early and accurate diagnosis and treatment are very important in the management of the disease.

18F-FDG PET is a well-established functional imaging technique for diagnostic oncologic imaging that provides data on glucose metabolism in lesions [3]. However, the technique allows the visualization not only of malignant cells but also of inflammatory cells [4, 5]. 18F-FDG PET has been proposed to play a role in the diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of sarcoidosis including cardiac involvement [6–25]. The Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the Japanese Society of Nuclear Cardiology (JSNC) recommend using 18F-FDG PET for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis [26, 27]. However, assessing inflammatory lesions in cardiac sarcoidosis using this modality can be challenging because 18F-FDG accumulates in normal myocardium, namely physiological uptake [11, 12]. Some of the main methods proposed for inhibiting increased 18F-FDG uptake in myocardial physiological cells include heparin injection, prolonged fasting, and dietary carbohydrate restriction before the 18F-FDG PET scan [11]. However, myocardial 18F-FDG uptake may be observed even under these conditions.

3′-Deoxy-3′-18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT) has been investigated as a promising PET tracer for evaluating tumor proliferative activity [28]. Zhao and colleagues in experimental rat studies reported that 3H-FLT uptake in granuloma was comparable to that in the tumor, whereas 3H-FLT uptake in turpentine oil-induced inflammation was significantly lower than that in the tumor [29]. 3H-FLT may accumulate in chronic granulomatous lesions with proliferative inflammation [29]. One case study of a patient with sarcoidosis showed mild 18F-FLT uptake and intense 18F-FDG uptake in lymph nodes [30]. To our knowledge, a previous report from our group was the first to describe positive findings on 18F-FLT PET/CT in a sarcoidosis patient with cardiac involvement [31]. In contrast to 18F-FDG, 18F-FLT uptake in the normal myocardium is low even in the absence of prolonged fasting or imposition of a special diet prior to imaging.

Limited information is available regarding the use of 18F-FLT in sarcoidosis. There have been no systematic studies, except the two case reports mentioned above [30, 31]. This prompted us to undertake the present study in which the uptake of 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG was compared in the evaluation of cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic involvement in patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by our institutional ethics review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

From March 2013 to March 2017, 41 consecutive patients with known or suspected sarcoidosis underwent both 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG PET/CT studies. Patients with a history of coronary artery disease, myocarditis, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy of unknown etiology, or uncontrolled diabetes mellitus were excluded. Patients treated with corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants were also excluded. Therefore, 20 patients (7 males, 13 females; mean age, 62 years; age range, 33–79 years) with clinical and/or histological diagnosis of sarcoidosis were included in this study. Cardiac sarcoidosis was defined based on the revised guidelines 2006, 2015, and 2016 for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis [27, 32, 33].

Radiotracer synthesis

18F-FLT and 18F-FDG were produced using a cyclotron (HM-18; Sumitomo Heavy Industries Co.). 18F-FLT was synthesized using the method described by Machulla et al. [34]. The radiochemical purity of the produced 18F-FLT was greater than 98%. 18F-FDG was produced by proton bombardment of 18O-enriched water by a modified method of Toorongian et al. [35]. The radiochemical purity of the produced 18F-FDG was greater than 95%.

PET/CT imaging

The patients fasted for at least 18 h before the 18F-FDG PET/CT scan. No special dietary instructions were given to patients before the 18F-FLT PET/CT scan. For 18F-FDG PET/CT, a normal blood glucose level in the peripheral blood was documented.

All acquisitions were performed using a Biograph mCT 64-slice PET/CT scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA Inc., Knoxville, TN, USA). Data acquisition began with CT at the following settings: no contrast agent, 120 kV, quality reference mAs, 100 mAs [using CARE Dose4D; Siemens], 0.5-s tube rotation time, 5-mm slice thickness, 5-mm increments, and pitch 0.8. PET emission scanning of the chest region with a 10-min acquisition of one-bed position was performed 60 min after intravenous injection of 18F-FLT or 18F-FDG (3.7 MBq/kg). The PET data were acquired in three-dimensional mode and were reconstructed by the baseline ordered-subsets expectation maximization bases, incorporating correction with point spread function and time-of-flight model (2 iterations, 21 subsets). A Gaussian filter with a full-width at half-maximum of 5 mm was used as a post-smoothing filter.

The 2 PET/CT scans were acquired within 4 weeks. No treatment was performed during this period.

Data analysis

The images were visually analyzed by two experienced nuclear physicians independently using a syngo.via (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Any difference of opinion was resolved by consensus. The images were evaluated for cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis. PET/CT fusion images were reviewed. For cardiac sarcoidosis, acquired images were also resliced into a series of short-axis, horizontal long-axis, and vertical long-axis images. Myocardial uptake of radiotracer was classified into four patterns: none, diffuse, focal, and focal on diffuse [13]. A focal or focal on diffuse pattern was considered as positive. A diffuse pattern was considered as inconclusive. For calculation of diagnostic accuracy, inconclusive was considered negative [36]. For extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis, focal increases in radioactivity seen in locations unaccounted for by the normal biodistribution of the radiotracer were considered as positive.

For semiquantitative analysis, a volume of interest was set to identify the maximum activity within the 18F-FLT- or 18F-FDG-positive lesion in cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic regions. Radioactivity concentrations were normalized to injected dose per patient’s body weight by calculation of standardized uptake value (SUV). The maximal SUV (SUVmax) for the lesion was calculated.

Statistical analysis

The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of PET/CT with each radiotracer for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis were calculated. The statistical significance was determined with the Fisher exact test. Differences in semiquantitative parameters were analyzed by a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Semiquantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD. Differences were considered statistically significant at the level of p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. Based on clinical and pathological criteria, 2 patients were diagnosed as having only cardiac sarcoidosis, 7 as having extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis (3 mediastinal/hilar lymph nodes and 4 mediastinal/hilar lymph nodes and lungs), and 11 as having both cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis (9 mediastinal/hilar lymph nodes and 2 mediastinal/hilar lymph nodes and lungs).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 20 patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis

| Patient no. | Age (years) | Sex | Selection criteria | Biopsy site | Organs involved | Myocardial uptake | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18F-FDG | 18F-FLT | ||||||

| 1 | 57 | F | Biopsy | LN | LN, heart | Focal | Focal |

| 2 | 46 | F | Biopsy | LN | LN, heart | Focal | Focal |

| 3 | 71 | F | Clinical diagnosis | LN, heart | Focal | Focal | |

| 4 | 58 | F | Clinical diagnosis | LN, heart | Focal | Focal | |

| 5 | 75 | F | Clinical diagnosis | LN, heart | Focal | Focal | |

| 6 | 68 | M | Biopsy | LN | LN, heart | Focal | Focal |

| 7 | 64 | M | Biopsy | Lung, LN | LN, heart | Focal | Focal |

| 8 | 76 | F | Clinical diagnosis | LN, heart | Focal | None | |

| 9 | 70 | F | Clinical diagnosis | LN, heart | Diffuse | Focal | |

| 10 | 52 | F | Clinical diagnosis | Lung, LN, heart | Focal | Focal | |

| 11 | 53 | F | Biopsy | Skin | Lung, LN, heart | Diffuse | Focal |

| 12 | 40 | M | Clinical diagnosis | Heart | Focal | Focal | |

| 13 | 67 | M | Clinical diagnosis | Heart | Focal | Focal | |

| 14 | 72 | M | Clinical diagnosis | LN | None | None | |

| 15 | 70 | M | Clinical diagnosis | LN | None | None | |

| 16 | 57 | F | Clinical diagnosis | LN | None | None | |

| 17 | 56 | F | Biopsy | Lung | Lung, LN | None | None |

| 18 | 72 | F | Biopsy | Skin | Lung, LN | None | None |

| 19 | 33 | M | Biopsy | LN | Lung, LN | Diffuse | None |

| 20 | 79 | F | Biopsy | Skin | Lung, LN | Diffuse | None |

LN lymph node

Detection of cardiac sarcoidosis

On the visual assessment of cardiac sarcoidosis, 4/20 18F-FDG scans were rated as inconclusive because the 18F-FDG pattern was diffuse. In contrast, no FLT scans were rated as inconclusive. Sensitivity of 18F-FDG PET/CT for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis was 85% (11/13), specificity 100% (7/7), and accuracy 90%. Sensitivity of 18F-FLT PET/CT for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis was 92% (12/13), specificity 100% (7/7), and accuracy 95%. With regard to these parameters, no significant differences were found between the 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT PET/CT studies.

In the semiquantitative assessment of cardiac sarcoidosis, the mean ± SD SUVmax for 18F-FDG (8.45 ± 3.50) was significantly higher than that for 18F-FLT (3.14 ± 0.89; p < 0.005).

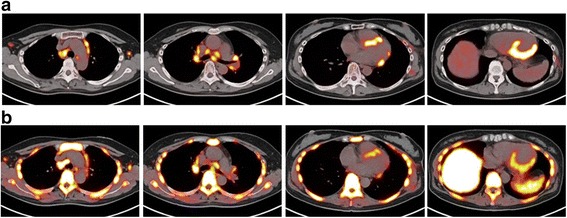

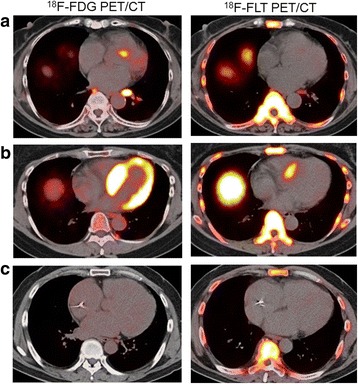

Figure 1 shows a typical case of newly diagnosed sarcoidosis detection by 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT PET/CT studies. Figure 2 shows 3 different patterns of cardiac uptake on 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT PET/CT studies.

Fig. 1.

PET/CT images of a 57-year-old female with cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis (patient 1 in Table 1). Transverse 18F-FDG (a) and 18F-FLT (b) PET/CT fusion images show increased uptake in the mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes, and focal uptake at the anteroseptal, inferoseptal, and inferolateral myocardium

Fig. 2.

The three different patterns of cardiac uptake on transverse 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT PET/CT fusion images at cardiac level include focal 18F-FDG uptake in the basal anteroseptal myocardium, with no corresponding uptake of 18F-FLT (patient 8 in Table 1) (a), diffuse 18F-FDG uptake and focal 18F-FLT uptake in the upper basal anteroseptal myocardium (patient 11 in Table 1) (b), and no 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT uptake in the myocardium (patient 14 in Table 1) (c)

Detection of extra-cardiac sarcoidosis

On visual assessment, both 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT PET/CT studies detected all 24 extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis (18 mediastinal/hilar lymph nodes and 6 lungs).

On the semiquantitative assessment of extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis, the mean ± SD SUVmax for 18F-FDG (9.89 ± 5.07) was significantly higher than that for 18F-FLT (4.91 ± 2.20; p < 0.001).

Discussion

In the present study of 20 patients with sarcoidosis, the detectability of cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic involvement using 18F-FLT PET/CT was comparable to that using 18F-FDG PET/CT. In particular, for evaluation of cardiac involvement, there was no inconclusive 18F-FLT PET/CT scan that required any special diet prior to imaging.

18F-FDG PET has been used in sarcoidosis including cardiac involvement for diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring [6–25]. 18F-FDG PET sensitivity was reported as 97–100% for detecting extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis [6–8], which is similar to the result of the present study (100%). A systematic review using 18F-FDG PET for detecting cardiac sarcoidosis indicated relatively high sensitivity (79–100%), which is also comparable to that of the present study (85%), but low specificity (38–100%) [9]. The present study showed a high specificity (100%). This may be attributable to inconclusive scans (diffuse pattern) that were considered negative. The reported specificity of 18F-FDG PET in diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis has been varied and relatively low compared with the sensitivity [9]. One possible reason for this low specificity and high variability may be the non-specific uptake of 18F-FDG in the normal myocardium caused by incompletely suppressed glycolytic metabolism [9]. Some studies have shown that an 18-h fast enhanced the quality of myocardial imaging with sufficient suppression of physiological uptake [10, 11]. In the present study, although patients fasted for 18 h prior to their 18F-FDG PET/CT scan, 4/20 scans did not show complete suppressing of physiological 18F-FDG uptake. Soussan et al. reported that 18F-FDG PET/CT after a high-fat and low-carbohydrate diet was a sensitive tool for the diagnosis of active cardiac sarcoidosis [15]. However, the diffuse pattern or focal uptake in the papillary muscle even under such dietary stipulations was still observed in 7/30 controls and 13/58 sarcoidosis patients [15]. A recent review by Osborne et al. reported that the available literature supported use of a high-fat, no-carbohydrate diet for at least two meals with a fast of 4–12 h prior to 18F-FDG PET imaging and suggested that isolated fasting for less than 12 h and supplementation with food or drink just prior to imaging should be avoided [37]. Ambrosini et al. reported cardiac FDG uptake regardless of the preparation before PET/CT, suggesting that even a meal rich in fat followed by 12 h of fasting, may not be sufficient to completely suppress physiological FDG uptake [16]. Despite the proper preparation, inadequate suppression of physiological uptake in myocardium can sometimes be experienced. More easily applicable and standardized preparation protocols should be established to sufficiently suppress physiological 18F-FDG uptake in the normal myocardium. Another possible reason for the low specificity observed in other studies is that myocardial ischemia and heart failure may also produce focally or heterogeneously increased 18F-FDG uptake not related to sarcoidosis. 18F-FDG PET may also visualize acute myocardial inflammation to suggest active myocarditis [38]. A meta-analysis for pulmonary lesion diagnosis reported that 18F-FLT showed better results compared with 18F-FDG in ruling out inflammation-based lesions [39]. A positive 18F-FDG PET finding in both cardiac and extra-cardiac regions is not specific to sarcoidosis.

An ideal radiopharmaceutical for imaging cardiac sarcoidosis should have no background uptake by normal myocardial cells and not be dependent on patient diet. 18F-FLT PET has no physiological uptake in the myocardium and does not require patients to adhere to prolonged fasting and/or a special diet prior to imaging. However, the uptake of 18F-FLT in sarcoidosis has not been elucidated yet. Zhao et al. developed a rat model of granuloma characterized by epithelioid cell granuloma formation and massive lymphocyte infiltration around the granuloma, histologically similar to sarcoidosis [29]. They showed that 3H-FLT uptake in the granuloma was comparable to that in the tumor, as in the case of 18F-FDG, although the level of 3H-FLT uptake was lower than that of 18F-FDG [29]. Sarcoidosis is suggested to be a granulomatous disease with high-turnover characteristics [30]. From an in vitro study using 3H-thymidine, there appear to be mostly low-turnover reactions, with occasional granulomas showing high-turnover characteristics, within the lymph node of a patient with sarcoidosis [40]. Active sarcoidosis may be a granulomatous disease with high-turnover characteristics, which could account for the increased 18F-FLT uptake in the present study. One case study of a patient with sarcoidosis showed a mild 18F-FLT uptake and intense 18F-FDG uptake in the involved lymph nodes [30]. In the present study, uptake of 18F-FLT in the involved lesions was also significantly lower than that of 18F-FDG. To the best of our knowledge, with the exception of two sporadic case reports [30, 31], the present study is the first investigation of 18F-FLT PET/CT undertaken for the detection of sarcoidosis. 18F-FLT may be a potentially useful tracer to combine with 18F-FDG in the detection of sarcoidosis, especially cardiac sarcoidosis.

18F-sodium fluoride (NaF) similarly has little myocardial uptake and is not dependent on patient preparation in terms of diet or insulin status similar to 18F-FLT. Recently, Weinberg et al. investigated 18F-NaF PET/CT for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis in three patients [41]. However, they reported that 18F-NaF may not be able to effectively image active inflammation due to cardiac sarcoidosis unlike 18F-FDG [41]. Gormsen et al. investigated the feasibility of 68Ga-DOTA-NaI-octreotide (DOTANOC) PET/CT, compared with 18F-FDG PET/CT, for the detection of cardiac sarcoidosis [36]. They showed that the diagnostic accuracy of 68Ga-DOTANOC in diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis was 100% although 11/19 18F-FDG scans were rated as inconclusive despite prolonged pre-scan fasting [36]. To date, there have been few studies using newer radiopharmaceuticals other than 18F-FDG for evaluation of sarcoidosis.

Limitations of the present study include a small sample size and retrospective design. Only 9 patients were diagnosed histologically, while none of those with cardiac sarcoidosis were diagnosed histologically by endomyocardial biopsy. Generally, endomyocardial biopsy shows lower sensitivity due to the heterogeneous distribution of the noncaseating granulomas that are characteristic of the disease. Given the limited sensitivity of myocardial biopsy, the revised guidelines 2006 [27], 2015 [32], and 2016 [33] have been used as the diagnostic standard. An important limitation of this study is the lack of significant dietary preparation with high-fat and low-carbohydrate meals prior to the 18F-FDG PET studies. Further studies to compare the 18F-FLT PET and 18F-FDG PET with such a dietary preparation will be needed and are currently underway. Unfortunately, in the present study, no data on whole-body scanning were available. Teirstein et al. reported that whole-body scan with 18F-FDG PET was particularly useful for detecting unsuspected extra-thoracic sarcoidosis [42]. They concluded that whole-body 18F-FDG PET was useful mainly in the detection of occult sites for biopsy and in the assessment of the presence of residual activity in patients with fibrotic pulmonary sarcoidosis, which may help to decide whether to continue or cease steroid therapy [42]. We did not compare PET imaging and myocardial perfusion imaging. Although 18F-FLT PET/CT could detect cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic sarcoidosis as well as 18F-FDG PET/CT, uptake of 18F-FLT in lesions was significantly lower than that of 18F-FDG. The lower level of uptake probably increases the detection limit, making it more difficult to visualize lesions. Pathology findings seen in sarcoidosis range from inflammatory cell infiltration, edema, noncaseating granuloma formation, and fibrotic changes to scarring [43]. Of these, 18F-FDG PET has limited ability to depict fibrous regions [24]. To date, no study has reported this issue using 18F-FLT PET. The combined use of 18F-FDG, 18F-FLT, other PET tracers, and other imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging might be helpful in the diagnosis and staging of cardiac sarcoidosis. Additional large prospective studies are needed to determine the clinical usefulness of 18F-FLT PET/CT in patients with sarcoidosis.

18F-FDG PET can monitor the disease activity of sarcoidosis including cardiac involvement, during and after steroid therapy [7, 16–22]. However, elevations in serum glucose and insulin levels due to steroid therapy may adversely affect 18F-FDG uptake in target organs including the heart and reduce test specificity [5, 17]. This may preclude accurate assessment of the effects of steroids using 18F-FDG PET. Although 18F-FLT PET might be useful for avoidance of such misleading evaluations, the role of 18F-FLT PET in steroid therapy monitoring has not been evaluated so far. Further prospective studies involving a larger number of patients will be required to determine the clinical usefulness of 18F-FLT PET in the diagnosis and monitoring the effects of steroid therapy in patients with sarcoidosis.

Conclusions

Based on the results of this preliminary study in a small patient sample, 18F-FLT PET/CT seems to be as effective as 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic involvement in patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis, although uptake of 18F-FLT in the lesions was significantly lower than that of 18F-FDG. However, since 18F-FLT PET/CT requires neither prolonged fasting nor a special diet prior to imaging, it may be a more convenient technique for evaluation of cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by KAKENHI Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JP17K16450) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Authors’ contributions

TN, YY, and YN conceived of and made the study design. TN, YM, TN, and HD carried out the data analysis and interpretation. TN, YY, and YN participated in the collection and assembly of the data. All authors drafted and edited the article and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

This comment refers to the article available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-017-0322-z.

This comment refers to the article available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-017-0322-0.

References

- 1.Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youssef G, Beanlands RS, Birnie DH, Nery PB. Cardiac sarcoidosis: applications of imaging in diagnosis and directing treatment. Heart. 2011;97:2078–2087. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2011.226076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman RE. Clinical PET in oncology. Clin Positron Imaging. 1998;1:15–30. doi: 10.1016/S1095-0397(97)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubota R, Yamada S, Kubota K, Ishikawa K, Tamahashi N, Ido T. Intratumoral distribution of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in vivo: high accumulation in macrophages and granulation tissues studied by microautoradiography. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1972–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alavi A, Gupta N, Alberini JL, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging in nonmalignant thoracic disorders. Semin Nucl Med. 2002;32:293–321. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2002.127291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishiyama Y, Yamamoto Y, Fukunaga K, et al. Comparative evaluation of 18F-FDG PET and 67Ga scintigraphy in patients with sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1571–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun JJ, Kessler R, Constantinesco A, Imperiale A. 18F-FDG PET/CT in sarcoidosis management: review and report of 20 cases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1537–1543. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada Y, Uchida Y, Tatsumi K, et al. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose and carbon-11-methionine evaluation of lymphadenopathy in sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1160–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Youssef G, Leung E, Mylonas I, et al. The use of 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta analysis including the Ontario experience. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:241–248. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langah R, Spicer K, Gebregziabher M, Gordon L. Effectiveness of prolonged fasting 18f-FDG PET-CT in the detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009;16:801–810. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morooka M, Moroi M, Uno K, et al. Long fasting is effective in inhibiting physiological myocardial 18F-FDG uptake and for evaluating active lesions of cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2014;4:1–11. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schatka I, Bengel FM. Advanced imaging of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:99–106. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.115121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishimaru S, Tsujino I, Takei T, et al. Focal uptake on 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography images indicates cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1538–1543. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohira H, Tsujino I, Ishimaru S, et al. Myocardial imaging with 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:933–941. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soussan M, Brillet PY, Nunes H, et al. Clinical value of a high-fat and low-carbohydrate diet before FDG-PET/CT for evaluation of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20:120–127. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambrosini V, Zompatori M, Fasano L, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT for the assessment of disease extension and activity in patients with sarcoidosis. Results of preliminary prospective study. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38:e171–e177. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31827a27df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, Kubo S, et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Multimodality imaging of cardiac sarcoidosis before and after steroid therapy. Circulation. 2006;113:e771–e773. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandya C, Brunken RC, Tchou P, Schoenhagen P, Culver DA. Detecting cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis: a call for prospective studies of newer imaging techniques. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:418–422. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00076406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tahara N, Tahara A, Nitta Y, et al. Heterogeneous myocardial FDG uptake and the disease activity in cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama R, Miyagawa M, Okayama H, et al. Quantitative analysis of myocardial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by PET/CT for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;195:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobic-Saranovic D, Artiko V, Obradovic V. FDG PET imaging in sarcoidosis. Semin Nucl Med. 2013;43:404–411. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamagishi H, Shirai N, Takagi M, et al. Identification of cardiac sarcoidosis with 13N-NH3/18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1030–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okumura W, Iwasaki T, Toyama T, et al. Usefulness of fasting 18F-FDG PET in identification of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1989–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohira H, Tsujino I, Yoshinaga K. 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in cardiac sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1773–1783. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1832-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manabe O, Ohira H, Yoshinaga K, et al. Elevated 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the interventricular septum is associated with atrioventricular block in patients with suspected cardiac involvement sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1558–1566. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1305–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishida Y, Yoshinaga K, Miyagawa M, et al. Recommendations for 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging for cardiac sarcoidosis: Japanese Society of Nuclear Cardiology recommendations. Ann Nucl Med. 2014;28:393–403. doi: 10.1007/s12149-014-0806-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shields AF, Grierson JR, Dohmen BM, et al. Imaging proliferation in vivo with [F-18]FLT and positron emission tomography. Nat Med. 1998;4:1334–1336. doi: 10.1038/3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao S, Kuge Y, Kohanawa M, et al. Usefulness of 11C-methionine for differentiating tumors from granulomas in experimental rat models: a comparison with 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:135–141. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.044578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SK, Im HJ, Kim W, Kim TS, Hwangbo B, Kim HJ. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose and F-18 fluorothymidine positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging in a case of neurosarcoidosis. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:67–70. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181c7c149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norikane T, Yamamoto Y, Maeda Y, Noma T, Nishiyama Y. 18F-FLT PET imaging in a patient with sarcoidosis with cardiac involvement. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:433–434. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diagnostic standard and guideline for sarcoidosis-2015. Available at: http://www.jssog.com/www/top/shindan/shindan2-1new.html. Accessed 17 Nov 2016. [in Japanese].

- 33.Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis (JCS 2016). Available at: http://www.j-circ.or.jp/guideline/. Accessed Feb 2017. [in Japanese].

- 34.Machulla HJ, Blocher A, Kuntzsch M, Piert M, Wei R, Grierson JR. Simplified labeling approach for synthesizing 3′-deoxy-3′-[18F]fluorothymidine ([18F]FLT) J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 2000;24:843–846. doi: 10.1023/A:1010684101509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toorongian SA, Mulholland GK, Jewett DM, Bachelor MA, Kilbourn MR. Routine production of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose by direct nucleophilic exchange on a quaternary 4-aminopyridinium resin. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1990;17:273–279. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(90)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gormsen LC, Haraldsen A, Kramer S, Dias AH, Kim WY, Borghammer P. A dual tracer 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT pilot study for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2016;6:52. doi: 10.1186/s13550-016-0207-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osborne MT, Hulten EA, Murthy VL, et al. Patient preparation for cardiac fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of inflammation. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:86–99. doi: 10.1007/s12350-016-0502-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kircher M, Lapa C. Novel noninvasive nuclear medicine imaging techniques for cardiac inflammation. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2017;10:6. doi: 10.1007/s12410-017-9400-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z, Wang Y, Sui X, et al. Performance of FLT-PET for pulmonary lesion diagnosis compared with traditional FDG-PET: a meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Gaag RD, van Maarsseveen AC, Broekhuizen-Davies JM, Stam J. Application of in-vitro techniques to determine proliferation in human sarcoid lymph nodes. J Pathol. 1983;139:239–245. doi: 10.1002/path.1711390302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinberg RL, Morgenstern R, DeLuca A, Chen J, Bokhari S. F-18 sodium fluoride PET/CT does not effectively image myocardial inflammation due to suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016 May 19; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Teirstein AS, Machac J, Almeida O, et al. Results of 188 whole-body fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scans in 137 patients with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2007;132:1949–1953. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohira H, Tsujino I, Sato T, et al. Early detection of cardiac sarcoid lesions with 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Intern Med. 2011;50:1207–1209. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.